Abstract

The hydrophobicity profile and sequence alignment of the Escherichia coli multidrug transporter MdfA indicate that it belongs to the 12-transmembrane-domain family of transporters. According to this prediction, MdfA contains a single membrane-embedded charged residue (Glu26), which was shown to play an important role in substrate recognition. To test the predicted secondary structure of MdfA, we analyzed complementary pairs of hybrids of MdfA-PhoA (alkaline phosphatase, functional in the periplasm) and MdfA-Cat (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, functional in the cytoplasm), generated in all the putative cytoplasmic and periplasmic loops of MdfA. Our results support the 12-transmembrane topology model and the suggestion that except for Glu26, no other charged residues are present in the membrane domain of MdfA. Surprisingly, by testing the ability of the truncated MdfA-Cat and MdfA-PhoA hybrids to confer multidrug resistance, we demonstrate that the entire C-terminal transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic C terminus are not essential for MdfA-mediated drug resistance and transport.

The simultaneous emergence of resistance in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells to many chemically unrelated drugs is termed multidrug resistance. Multidrug (Mdr) transporters that convey the drugs from the cell cytoplasm or cytoplasmic membrane to the external medium induce one major form of multidrug resistance. Secondary Mdr transporters are widely distributed among prokaryotic microorganisms, including pathogenic bacteria (17, 19, 24, 28, 33, 34, 36), and many of them are driven by the transmembrane proton electrochemical gradient (5, 10, 11, 12, 21, 22).

The prokaryotic Mdr transporters can extrude a variety of chemically unrelated lipophilic compounds, many of which tend to be positively charged under physiological conditions. However, there are also bacterial Mdr transporters that interact with neutral drugs, some of which are relatively hydrophilic, and some transporters export lipophilic anionic drugs (20). These properties of the Mdr transporters also pose, in addition to a potential clinical threat (29), intriguing questions regarding substrate recognition and transport mechanism. Interestingly, we have recently shown that the Escherichia coli Mdr transporter MdfA interacts simultaneously with a pair of substrates, cationic and neutral (18). Although the two binding sites (for tetraphenylphosphonium [TPP+] and chloramphenicol) are closely related, only the transport of some cationic substrates requires a membrane-embedded negative charge at position 26 of the transporter (11; J. Adler and E. Bibi, unpublished data).

MdfA (also termed Cmr) (30) is a 410-amino-acid membrane protein from the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of secondary transporters. Recently, close MdfA homologues were identified in the pathogenic bacteria Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (90% identity) (32) and Yersinia pestis (73% identity) (31). Cells expressing MdfA from a multicopy plasmid exhibit multidrug resistance to a diverse group of cationic, zwitterionic, and neutral compounds (reviewed in reference 3).

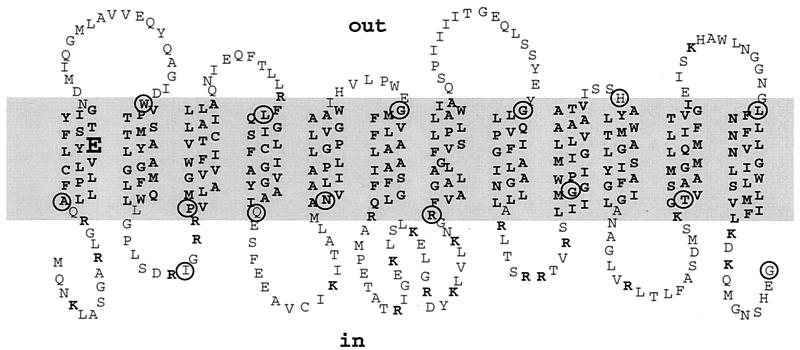

Transport experiments have shown that MdfA is an Mdr transporter that is driven by the proton electrochemical gradient (10) and functions as a drug/proton antiporter (27). Based on its hydrophobicity profile (15), the “positive inside rule” (39), and the homology for better-characterized MFS transporters, a secondary structure model was constructed for MdfA (10). This model predicts that MdfA contains 12 transmembrane segments (TMs) with the N and C termini facing the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). In addition, according to this prediction, the putative TMs of MdfA are very hydrophobic and contain a single membrane-embedded charged amino acid residue, glutamate at position 26, in the middle of putative TM1. As indicated above, this negative charge is important for the recognition of some cationic drugs by MdfA. However, our assumption that Glu26 is the only membrane-embedded charged residue is based on theoretical considerations and limited experimental data (3).

FIG. 1.

Secondary-structure model for MdfA based on the hydropathy profile and the distribution of positively charged residues (indicated in boldface type). Sites of fusions between MdfA and PhoA/Cat are circled, and the conserved glutamate residue is emphasized.

In this study, the validity of the proposed topological model was examined by gene fusions between MdfA and two sensor enzymes which reflect opposite subcellular dispositions. One reporter is the mature form of alkaline phosphatase (PhoA, encoded by the phoA gene) (23), a periplasmic protein that must be exported to the periplasm to be enzymatically active. In this way, PhoA acts as a sensor for the periplasmic location of the protein sequence to which it is attached (9). However, when PhoA is used as the sole topological reporter, the results interpreted are limited to periplasmic fusion joints, whereas the localization of fusion joints to the cytoplasm can only be speculated because it is based on negative results (the absence of alkaline phosphatase activities).

Therefore, in addition to PhoA, we used a complementary approach with the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cat) enzyme as a cytoplasmic reporter (41). Hybrids between a membrane protein and Cat should exhibit a reciprocal pattern of activities (compared to hybrids with PhoA), since Cat is biologically functional (confers substantial chloramphenicol resistance) only when fused to cytoplasmic loops of membrane proteins (13, 41).

Here, pairs of MdfA-PhoA and MdfA-Cat hybrids with identical fusion joints were analyzed in detail, and the results support the proposed secondary structure model of MdfA and the suggestion that Glu26 is located inside TM1. No other membrane-embedded charged residue could be identified by using this specific set of hybrids. Finally, having a library of truncated MdfA constructs, we tested the ability of the various hybrids to confer drug resistance. Surprisingly, the results clearly demonstrate that the entire C-terminal transmembrane segment and the cytoplasmic tail of MdfA are not essential for its multidrug resistance function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

[35S]methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham Corp. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), ethidium bromide (EtBr), chloramphenicol, kanamycin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, puromycin, and protein A were purchased from Sigma. TPP+ was obtained from Fluka, and benzalkonium chloride was from Calbiochem. Restriction and modifying enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs. Oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized by the scientific services unit at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Polyclonal antibodies to alkaline phosphatase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cat) were from Rockland and from 5 Prime-3 Prime, Inc., respectively. All other materials were reagent grade and obtained from commercial sources.

Bacterial strains.

E. coli HB101 [hsdS20 (rB− mB−) recA1 ara-14 proA2 lacY galK2 rpsL20 (Smrr) xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44 λ−/F−] was used for the propagation and preparation of various plasmid constructs. E. coli UT mdfA::kan (R. Edgar and E. Bibi, unpublished data) and the leaky strain UTL2 mdfA::kan (11) were used in drug resistance and transport experiments. E. coli CC181 [araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 ΔlacY X74 phoAΔ20 galE galK thi rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recAI/F′ lacIq lacY328(Am) pro] was used for metabolic labeling of MdfA-PhoA fusions and for measuring the alkaline phosphatase activity of the hybrid proteins. E. coli T184 [lacI+O+Z−Y−(A) rpsL met thr recA hsdM hsdR/F′ lacIqO+ZD118(Y+A+)] was used for expression of MdfA-Cat fusions for efficient methionine starvation and better [35S]methionine labeling of the induced proteins.

Construction of MdfA-PhoA fusions.

For controlled expression of the protein, mdfA tagged with phoA (devoid of the leader peptide-coding sequence) (2) was placed under the araB promoter in plasmid pT7-5, also encoding araC. The resulting construct, pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA, provided increased and tightly regulated expression of MdfA with arabinose as an inducer (data not shown). In the vector pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA, the phoA gene is fused to the 3′ end of mdfA with a unique NheI restriction site in the junction.

Using synthetic deoxyoligonucleotides (not shown) and PCR, we constructed a series of fusions between mdfA and phoA. The fusions (to codons I79, L114, Q131, N148, G172, R220, G258, G291, H311, T348, and L379) were designed to contain an NheI site at the 3′ end immediately after the junction codon and another mdfA unique site at the 5′ end. The vector and each of the mdfA PCR fragments were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated to form the various mdfA-phoA constructs. Plasmids prepared from positive transformants were analyzed by restriction analysis and by sequencing of the PCR-amplified region.

In order to examine the drug resistance media by the truncated mutants, we had to reduce the expression level of the otherwise toxic MdfA constructs. For this purpose, the two C-terminal MdfA-PhoA fusions (T348 and L379) were transferred from pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA (a system producing a high level of expression) to the plasmid pT7-5/mdfA-phoA, containing the native promoter of mdfA. In addition, it was important to examine the activity of the truncated MdfA mutants without any possible interference by C-terminal extensions (such as PhoA or Cat). Therefore, we introduced a stop codon at position T348 (N10 MdfA) or L379 (N11 MdfA) as follows. The starting plasmids (pT7-5 /N10mdfA-phoA and pT7-5 /N11mdfA-phoA) contain the unique NheI site at the junction between mdfA and phoA and the unique XbaI site downstream of the phoA gene. The plasmids were digested with both NheI and XbaI to release phoA, then treated with DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment, and ligated to produce stop codons at position T348 or L379.

Construction of MdfA-Cat fusions.

For complementary topological studies, the Cat-encoding sequence was inserted instead of the phoA gene in all the MdfA-PhoA hybrids. In addition, three short MdfA-Cat hybrids were constructed in order to complement the previously described MdfA-PhoA hybrids in the region of TM1 and TM2 (11). Initially, the full-length MdfA-Cat fusion was generated by replacement of the phoA gene in pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA by the cat gene (41). The resulting plasmid, pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-cat, was then used to construct a series of fusions between MdfA, truncated at the same codons as with PhoA, and Cat. Briefly, pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA truncated at I79, L114, Q131, N148, G172, R220, G258, G291, H311, T348, and L379 was digested by Eco47IIIand NheI restriction endonucleases to obtain mdfA truncated in the indicated positions. The resulting inserts were ligated to the pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-cat vector treated with the same two enzymes. In addition, plasmid pT7-5/mdfA-phoA truncated at A15, W53, and P83 (11) was digested with AatII and then with NheI to obtain A15-, W53-, and P83-truncated mdfA genes. These inserts were then ligated to the pT7-5 /araBC/mdfA-cat vector partially digested with AatII and then with NheI.

[35S]methionine labeling and immunoprecipitation.

E. coli cells (CC181 or T148) expressing the MdfA-PhoA or MdfA-Cat hybrids, respectively, or harboring the plain vector as the control were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. Cells were diluted 1:20 and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 to 0.6. The cells were then washed and resuspended in M9 minimal medium containing 0.4% glycerol, 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 μg of thiamine per ml, and all the amino acids (15 μg/ml) except for methionine and cysteine, and starved for 3.5 h at 37°C. The cultures were then induced with 0.2% arabinose for 40 min. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of the cultures (OD420 = 0.6) were labeled for 5 min with 20 μCi of [35S]methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). Where indicated, an excess of unlabeled methionine (final concentration, 20 mM) was added, and the incubation was continued up to an additional 4 h. Proteins were immunoprecipitated, as described previously (2), using antibodies to alkaline phosphatase or to Cat. Immunoprecipitated material was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 10% polyacrylamide in the running gel and subjected to autoradiography. The radioactive bands were quantitated by a densitometer.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of MdfA-PhoA hybrids.

The same cultures of E. coli that were grown for [35S]methionine labeling of MdfA-PhoA hybrids were also assayed for alkaline phosphatase activity by measuring the rate of hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate in permeabilized cells (2). The alkaline phosphatase activity was calculated according to Brickman and Beckwith (8).

Drug resistance assays.

The resistance of cells harboring the indicated plasmids with mdfA constructs under control of the native promoter was assayed qualitatively in solid medium, as described elsewhere (10, 40). Semiquantitative growth assays in liquid medium were carried out as described previously (10).

Efflux of EtBr.

Efflux of EtBr from E. coli UTL2 mdfA::kan cells harboring plain vector or the indicated plasmids with mdfA constructs under control of the native promoter was monitored as described (10), with modifications. Overnight cultures were diluted to 0.04 OD600 unit and grown at 37°C in LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) to 0.9 to 1.0 OD600 unit. Harvested cells were suspended in 2 ml of KPi buffer (K2HPO4, KH2PO4, 50 mM, pH 7.0) to 0.3 OD600 U and loaded with EtBr (5 μM) at 37°C for 5 min in the presence of CCCP (100 μM). Loaded cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in the same buffer containing only EtBr (5 μM), and subjected to fluorescence measurements. After approximately 1 min in the fluorimeter, glucose was added (final concentration, 0.4%). EtBr efflux was monitored continuously by measuring the fluorescence, using excitation and emission wavelengths of 545 and 610 nm, respectively.

Western blotting.

Overnight cultures of E. coli UTL2 mdfA::kan cells harboring MdfA-encoding plasmid constructs were diluted 1:50 in LB supplemented with the antibiotics ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml), and grown to an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.7. The cultures were harvested, and membranes were prepared as described previously (4). The membrane fractions were then subjected to SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide in the running gel. Finally, the proteins were electroblotted to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with rabbit anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibodies.

RESULTS

Characterization of MdfA-PhoA hybrids.

Previously, by analyzing short MdfA-PhoA hybrids, the putative topology of TM1 and TM2 was tested. In these hybrids PhoA was fused to amino acid residues A15, I31, V43, W53, and P83 (11). Therefore, in the present study we first analyzed the topology of the rest of the protein by constructing additional MdfA-PhoA hybrids, starting at position I79 (Fig. 1). For controlled expression of the hybrids, mdfA was placed under regulation of the araB promoter in a pT7-5 plasmid, which also encodes the repressor araC. The resulting construct (pT7-5/araBC/mdfA-phoA) enabled tight regulation of MdfA expression by induction with arabinose (data not shown). In general, gene fusions were designed so that at least one fusion in each loop was placed at the C-terminal portion of that loop. This design should prevent the disruption of known topological determinants, such as positively charged residues, normally located in the internal loops (7).

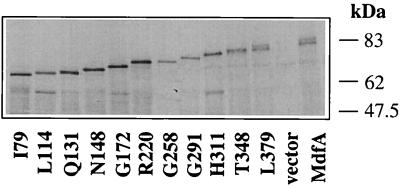

The experiments were performed with an E. coli strain lacking the phoA gene (CC181) in order to achieve a better signal-to-noise ratio. Each MdfA-PhoA hybrid was analyzed for expression and alkaline phosphatase activity, and importantly, both the expression and activity were tested in cells withdrawn from the same culture. The expression level of the fusion proteins was estimated by [35S]methionine labeling, immunoprecipitation with anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies, SDS-PAGE, and autoradiography. The results demonstrate that all the immunoprecipitated products migrated according to the expected increase in molecular weight between sequential hybrids (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Expression of MdfA-PhoA fusion proteins in E. coli CC181 cells. Cells were induced for 40 min with 0.2% arabinose and then labeled for 5 min by [35S]methionine. Fusion proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies and then subjected to SDS-PAGE (10%) and autoradiography. The positions of the molecular size standards are shown.

Although all the hybrids were expressed, their expression levels differed. The band intensities are generally reduced as the size of the hybrid protein increases, despite the fact that the methionine residue content increases. This may be attributed either to decreased expression or to the instability of longer polypeptides. In this regard, only hybrids L114, G172, and H311 exhibited minor proteolytic products that contain PhoA. Since it is possible that a certain proteolytic product exhibits alkaline phosphatase activity as well as its precursor (the appropriate full-length hybrid), this was also considered in calculating the normalized alkaline phosphatase activities. The bands representing the expected full-length chimeric proteins or the full-length hybrids combined with the appropriate major proteolytic products were quantitated by densitometry (Table 1). In addition, the number of methionine residues was taken into account, since [35S]methionine was used for labeling. For example, the longest hybrid protein (MdfA-PhoA) contains 25 methionine residues, whereas the shortest hybrid protein (I79) contains only 12. The level of expression (band intensity) divided by the number of methionines was then used as a normalization factor for calculating the normalized alkaline phosphatase activity (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Normalized alkaline phosphatase activity of MdfA-PhoA hybrids in E. coli CC181 cells

| MdfA-PhoA hybrid | No. of methionines | Alkaline phosphatase activitya (arbitrary units) | Expression level (pixels/1,000) | Normalized activityb | Predicted PhoA location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I79 | 12 | 0 | 6.53 | 0 | In |

| L114 | 13 | 17.1 | 5.13 | 43 | Out |

| Q131 | 13 | 1.5 | 2.45 | 8 | In |

| N148 | 14 | 0.5 | 2.73 | 3 | In |

| G172 | 14 | 46.8 | 6.57 | 100 | Out |

| R220 | 16 | 0 | 2.77 | 0 | In |

| G258 | 16 | 44.8 | 0.95 | 757 | Out |

| G291 | 17 | 0.9 | 2.60 | 6 | In |

| H311 | 18 | 35.4 | 4.89 | 130 | Out |

| T348 | 20 | 1.4 | 1.83 | 15 | In |

| G379 | 23 | 46.7 | 1.54 | 695 | Out |

| MdfA | 25 | 1.9 | 2.06 | 23 | In |

Following subtraction of the basal activity in cells harboring plain vector.

Normalized alkaline phosphatase activity = [(activity × number of methionines)/expression level].

The results enable a clear distinction to be made between external and putative internal hybrids. Hybrids I79, Q131, N148, R220, G291, T348, and MdfA-PhoA (full-length) exhibited low normalized alkaline phosphatase activity (0 to 23 U), reflecting their putative cytoplasmic location as predicted (Fig. 1). Also as expected, fusions L114, G172, G258, H311, and G379 exhibited relatively high alkaline phosphatase activities (43 to 757 U), in accordance with their proposed periplasmic location. In conclusion, the results obtained with the periplasmic reporter PhoA are consistent with the 12-TM secondary structure model of MdfA.

Characterization of MdfA-Cat hybrids.

In searching for a PhoA-complementary reporter, we compared the applicability of two proteins, β-galactosidase (LacZ) and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cat). When LacZ is attached to cytoplasmic loops of a membrane protein, the resulting hybrids usually exhibit high levels of enzymatic activity. In hybrids of LacZ to periplasmic domains, LacZ gets trapped inside the membrane, resulting in a loss of enzymatic activity (16). In a preliminary test, we examined the expression and activity of three MdfA-LacZ and MdfA-Cat hybrids (T348, L379, and the full-length MdfA). Although the enzymatic activities of all the hybrids reciprocally complemented the activity of identical MdfA-PhoA hybrids (data not shown), the MdfA-LacZ hybrids were significantly less stable than the MdfA-Cat hybrids, possibly because of proteolytic degradation (data not shown). Therefore, the cytoplasmic Cat was chosen as a reporter for the complementary topological studies of MdfA.

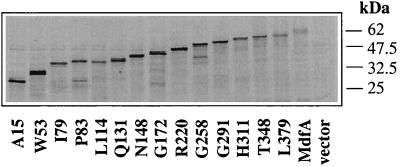

The Cat-encoding sequence was inserted instead of phoA in all the plasmids that encode MdfA-PhoA hybrids. In addition, three short MdfA-Cat hybrids were constructed to complement the previously described MdfA-PhoA hybrids in the region of TM1 and TM2 (11). The expression of all the resulting hybrids was investigated by labeling with [35S]methionine and immunoprecipitation with anti-Cat antibodies (Fig. 3). As shown, all the hybrids were expressed, and except for hybrid P83, which migrated slightly slower than expected, the sizes of the MdfA-Cat hybrids increased gradually, as expected. The expression level of the MdfA-Cat hybrids was variable, but unlike the expression of the MdfA-PhoA hybrids, which decreased as a function of length, there was no correlation between the expression levels of the MdfA-Cat hybrids and the predicted locations of the Cat reporters or the length of the hybrids.

FIG. 3.

Expression of MdfA-Cat fusion proteins in E. coli T184 cells. Cells were induced for 40 min with 0.2% arabinose and then labeled for 5 min by [35S]methionine. Fusion proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cat antibodies and then subjected to SDS-PAGE (12.5%) and autoradiography. The positions of the molecular size standards are shown.

To test the ability of the MdfA-Cat hybrids to confer chloramphenicol resistance (as topological criteria), we performed antibiotic resistance assays. Briefly, cells transformed with plasmids harboring different mdfA-cat constructs were plated on chloramphenicol-containing LB agar plates, and their ability to form single colonies was tested at different chloramphenicol concentrations. As shown in Table 2, cells expressing hybrids A15, I79, P83, Q131, N148, R220, G291, T348, and MdfA-Cat (full-length) exhibited relatively high resistance to chloramphenicol (7 to 20 μg/ml), supporting their predicted cytoplasmic orientation. Among the active MdfA-Cat hybrids, the shorter versions (A15, I79, P83, Q131, N148, and R220) were able to confer high-level resistance to the drug (15 to 20 μg/ml). The most potent hybrid was A15-Cat, probably because it includes only the amino-terminal cytoplasmic domain of MdfA and therefore is the only hybrid that is not attached to the membrane.

TABLE 2.

Chloramphenicol resistance conferred by MdfA-Cat hybrids

| MdfA-Cat hybrid | Growtha in chloramphenicol (μg/ml):

|

Predicted Cat location | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 20 | ||

| A15 | + | + | + | + | + | + | In |

| W53 | + | − | − | − | − | − | Out |

| I79 | + | + | + | + | + | − | In |

| P83 | + | + | + | + | + | − | In |

| L114 | + | − | − | − | − | − | Out |

| Q131 | + | + | + | + | + | − | In |

| N148 | + | + | + | + | + | − | In |

| G172 | + | − | − | − | − | − | Out |

| R220 | + | + | + | + | + | − | In |

| G258 | + | − | − | − | − | − | Out |

| G291 | + | + | + | + | − | − | In |

| H311 | + | − | − | − | − | − | Out |

| T348 | + | + | + | + | − | − | In |

| L379 | + | + | − | − | − | − | Out |

| MdfA | + | + | + | + | − | − | In |

| Vector | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

+, formation of single colonies after incubation overnight at 37°C; −, no growth.

The other biologically active MdfA-Cat hybrids (G291, T348, and MdfA-Cat) conferred somewhat lower levels of chloramphenicol resistance (≈10 μg/ml). In contrast, hybrids W53, L114, G172, G258, and H311 were unable to confer resistance, even with a relatively low chloramphenicol concentration (4 μg/ml), possibly because of the periplasmic location of Cat in these fusions. All together, the MdfA-Cat and MdfA-PhoA hybrids complement each other in providing strong support for the proposed topological model of MdfA (Fig. 1).

MdfA lacking TM12 confers significant multidrug resistance.

Surprisingly, the MdfA-Cat hybrid L379 was able to confer low but significant resistance to chloramphenicol (Table 2), despite its putative external disposition, as demonstrated by the high alkaline phosphatase activity of the MdfA-PhoA hybrid at the same position. This truncated MdfA mutant, which contains only the N-terminal 11 TMs (Fig. 1), was termed N11. The ability of N11-Cat to confer chloramphenicol resistance could result from improper folding of a subpopulation of the chimeric protein in the membrane, thus exposing Cat on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane. Alternatively, it is possible that the truncated MdfA mutant itself, without the fused Cat, is able to export chloramphenicol.

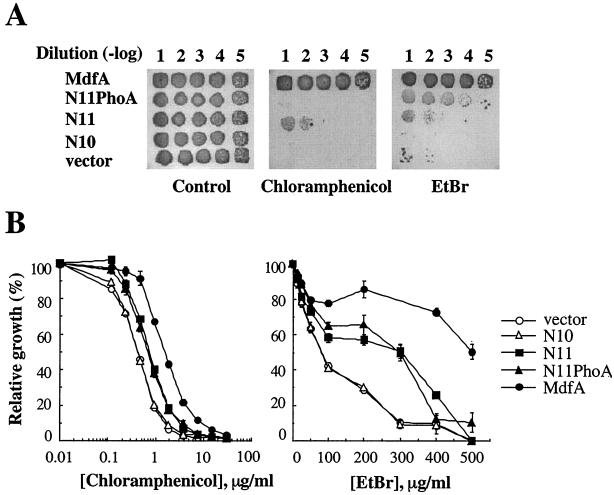

In order to distinguish between these possibilities, cells expressing N11-PhoA, which does not contain Cat, were tested in drug resistance assays. For these assays we used the relatively low expression vector pT7-5 /mdfA (11). E. coli UT mdfA::kan was transformed with pT7-5/N11-phoA, and various dilutions were plated onto LB agar plates containing the indicated drugs (Fig. 4A). In addition, a truncated MdfA mutant with a stop codon at position L379 (N11) was constructed, to avoid possible interference by C-terminal extensions. Remarkably, although not identical, both N11-PhoA and N11 (with no PhoA extension) were able to confer resistance to chloramphenicol and EtBr (Fig. 4). N11-PhoA conferred higher resistance to EtBr, whereas the truncated mutant N11 conferred higher resistance to chloramphenicol. Further shortening of MdfA (N10, MdfA truncated at position T348) completely abolished its drug resistance activity to either chloramphenicol or EtBr (Fig. 4A). In general, similar results were obtained in liquid medium, with the drug sensitive E. coli strain UTL2 mdfA::kan.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of truncated mutants of MdfA. (A) Overnight cultures of E. coli UT mdfA::kan cells transformed with pT7-5 (vector), wild-type pT7-5/mdfA, or the mutants were diluted (10−1 to 10−5), and 10 μl of diluted cultures was spotted on LB agar plates with ampicillin (200 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) (control) and on plates supplemented also with chloramphenicol (4 μg/ml) or EtBr (450 μg/ml). Growth was analyzed after overnight incubation at 37°C. (B) Relative growth (calculated from the cell density, measured by the absorption at 600 nm) of UTL2 mdfA::kan cells harboring the above plasmids in LB broth containing increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol or EtBr. Two independent experiments were conducted in quadruplicate, and the results shown are representative.

In comparison to the full-length MdfA, the level of resistance conferred by N11 (with or without fused PhoA) was intermediate. As shown in Fig. 4B (left panel), the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of chloramphenicol is 2 μg/ml for cells expressing wild-type MdfA, 1 μg/ml for N11, and only 0.3 μg/ml for N10 or plain vector. When tested with EtBr, its IC50 for cells expressing N11 is 300 μg/ml, compared to an IC50 of 500 μg/ml with wild-type MdfA. In contrast, N10 completely failed to confer resistance to EtBr, and cells harboring N10 grew essentially as E. coli harboring a plain vector, with an EtBr IC50 of only 100 μg/ml. Thus, we conclude that although TM12 of MdfA is not essential for its function, it contains important determinants required for optimal activity.

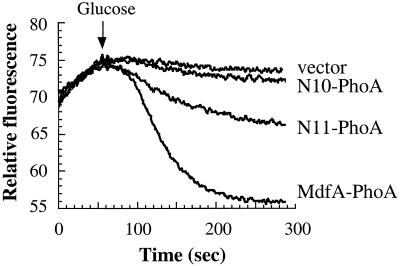

In order to test whether the truncation of TM12 affects the previously demonstrated broad drug recognition spectrum of MdfA (10), we tested the ability of N11 to confer resistance to additional drugs. Interestingly, N11 exhibited an altered pattern of drug resistance compared with the wild-type MdfA. In a reproducible manner, N11 was able to confer a substantial level of resistance to EtBr, benzalkonium, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol. However, unlike wild-type MdfA, N11 was unable to confer resistance to puromycin, TPP+, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin (data not shown). These results suggest that N11 is unable to transport poor substrates of MdfA (10). Alternatively, it cannot be excluded that TM12 and the C-terminal tail of MdfA might have a role in maintaining the full substrate recognition profile of MdfA. Finally, the activity of the truncation mutants was also measured directly by transport assays. As shown (Fig. 5), cells expressing N11 exhibit low but significant EtBr efflux activity, whereas cells with N10 behave like control cells without MdfA.

FIG. 5.

Transport activity of truncated MdfA mutants. Efflux of EtBr was monitored continuously by following its fluorescence (which is increased upon interaction of the compound with DNA and RNA), as described in Materials and Methods. Glucose (0.4%) was added to energize transport. Efflux of EtBr is represented by a decrease in fluorescence.

Expression and stability of the truncated MdfA mutants.

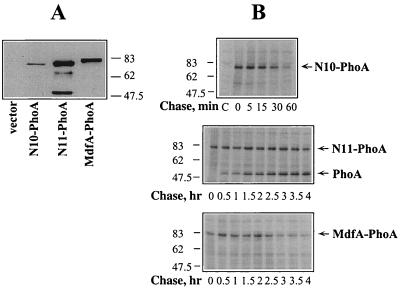

To determine whether the low activity of the truncated mutants reflects fewer transporter molecules in the membrane at steady state, membranes were prepared from cells expressing N10-PhoA, N11-PhoA, or MdfA-PhoA and analyzed by Western blotting. The expression from the relatively low expression system with plasmid pT7-5/mdfA-phoA (Fig. 6A) was analyzed. As mentioned in the previous section of the Results, drug resistance experiments were performed under the same conditions. As shown in Fig. 6A, the steady-state amount of N11-PhoA in the membrane was similar to that of full-length MdfA-PhoA. However, in addition to a band corresponding to N11-PhoA, other, lower-molecular-weight bands were recognized by the anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies. These observations suggest that despite its normal or elevated expression level, N11-PhoA is unstable. The steady-state level of N10-PhoA under these conditions was very low.

FIG. 6.

Expression and stability of wild-type MdfA and truncated mutants. (A) Immunoblot of membrane fractions (10 μg of crude membrane protein) from E. coli UTL2 mdfA::kan harboring pT7-5/mdfA-phoA. (B) E. coli T184 cells harboring MdfA-PhoA hybrids or vector (control, C) were induced for 40 min with 0.2% arabinose and labeled for 5 min by [35S]methionine. After the addition of excess unlabeled methionine (20 mM), samples were taken at the indicated times. Fusion proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies and then subjected to SDS-PAGE (10%) and autoradiography. The positions of molecular size standards are shown (in kilodaltons).

In order to test whether both N11-PhoA and N10-PhoA are sensitive to proteolysis, cells expressing wild-type MdfA-PhoA, the two truncated hybrids, or cells harboring the plain vector were induced with arabinose and pulse labeled with [35S]methionine. After 5 min of labeling, an excess of unlabeled methionine was added, and the incubation was continued for up to 4 h. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated times, and the hybrids were immunoprecipitated with anti-alkaline phosphatase antibodies. Figure 6B shows that efficient and specific immunoprecipitation was attained in all cases. As shown, the intensity of the radioactive bands corresponding to all the hybrids gradually decreased.

MdfA-PhoA is estimated to have a half-life of about 3 h (Fig. 6B, lower panel). In contrast, N10-PhoA was degraded rapidly, with a half-life of about 30 min (upper panel). No major alkaline phosphatase-related proteolytic fragments were observed in both cases (with N10-PhoA and MdfA-PhoA), suggesting that here complete degradation occurs. In contrast to the rapid turnover of N10-PhoA, hybrid N11-PhoA is much more stable, with a half-life of about 4 h (middle panel), which is even longer than that of the full-length MdfA-PhoA hybrid. Interestingly, however, although the intensity of the band representing N11-PhoA decreased very slowly, a prominent proteolytic product corresponding to mature alkaline phosphatase accumulated very rapidly (Fig. 6B, middle panel). This band was also clearly observed in the immunoblot analysis of the steady-state level of N11-PhoA (see Fig. 6A).

The pulse-chase studies demonstrate that although the rate of synthesis of N11-PhoA is significantly higher than that of the other hybrids, it is degraded rapidly and its resulting steady-state amount in the membrane is similar to that of MdfA-PhoA. In contrast to N11-PhoA, N10-PhoA is significantly less stable, its steady-state amount is greatly reduced, and, thus, its ability to confer drug resistance cannot be analyzed in vivo. In conclusion, the low Mdr activity of N11-PhoA probably does not reflect expression problems, but rather the fact that although not essential, TM12 and the C-terminal tail of MdfA are important for maintaining the fully functional form of the transporter.

DISCUSSION

Structural information is a prerequisite for determining the molecular mechanism of multispecific substrate recognition by Mdr transporters. Here we have presented a detailed topological analysis of the multidrug transporter MdfA. Based on the positive inside rule (39), the hydropathy profile (15), and the homology with other characterized MFS proteins, a secondary structure model was constructed for MdfA (10). This model predicts that MdfA contains 12 TMs with the N and C termini on the cytoplasmatic side of the membrane and a single membrane-embedded charged residue. In order to test this prediction, we used both alkaline phosphatase (23) and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (41) as reporters in gene fusion studies. PhoA and Cat complement each other because PhoA is functional only when exported to the periplasm, whereas Cat is biologically active only when expressed in the cytoplasm.

The properties of both the MdfA-PhoA and MdfA-Cat hybrids further support the proposed 12-TM model. More specifically, all the fusions (PhoA and Cat) at predicted cytoplasmic sites exhibit low alkaline phosphatase activity and high chloramphenicol resistance, and all the predicted periplasmic hybrids exhibit high alkaline phosphatase activity and low chloramphenicol resistance. Importantly, by using two complementary reporters (PhoA and Cat) for each fusion, the interpretation of the results is based mainly on positive signals. Previous studies demonstrated that the negative charge of the Glu26 residue, located within the first TM segment, is important for substrate recognition of some positively charged drugs by MdfA (11; J. Adler and E. Bibi, unpublished data). However, since Glu26 was found to be nonessential for chloramphenicol export and thus does not play a role in proton translocation, it was postulated that other charged residues might also exist inside membrane domains of MdfA.

The present studies, however, do not support this hypothesis and therefore raise the possibility that proton translocation by MdfA may not be mediated by charged residues, at least in the membrane portion of the protein. However, it should be noted that the experimental resolution level of the gene fusion approach is not sufficient for precise localization of the cytoplasmic or periplasmic interfaces of the TMs. Therefore, additional structural studies, using complementary methods, are needed to examine further the possibility that MdfA contains a single charged residue inside the membrane domain.

These studies also led to the interesting observation that the entire TM12 and the C-terminal tail of MdfA are not essential for its function as an Mdr transporter. In fact, the deleted sequence (31 amino acid residues) does not appear to be involved either in the expression of MdfA in the membrane or in maintaining a functional conformation. Nevertheless, since N11 is significantly less active than wild-type MdfA, the truncated sequence is not completely dispensable. Further truncation of MdfA (N10) destabilizes the protein, and therefore the exact reason for its abolished Mdr activity could not be analyzed directly.

The minimal structural requirements for insertion, stability, and functioning of polytopic membrane transporters have been analyzed in several cases. Deletion of the carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail in polytopic membrane proteins usually causes negligible effects on stability and activity. The E. coli LacY is stable and completely functional after the C-terminal cytosolic tail is deleted (37). Similarly, the cytosolic C terminus of MelB from E. coli is not required for substrate recognition or energy transduction (6), and the C-terminal hydrophilic tail of the E. coli tetracycline transporter is dispensable without loss of stability and activity (38). In contrast, removal of residues from the last TM usually leads to loss of stability and the activity of membrane transporters. Indeed, truncation of five residues from the carboxy-terminal portion of TM12 of LacY abolished proper folding and lactose transport activity (37, 25, 26). Similarly, MelB truncated of its TM12 was no longer found in the membrane (6), and the tetracycline transporter was inactive and degraded rapidly when its TM12 was deleted (38). With the Staphylococcus aureus Mdr transporter QacA, it was shown that all 14 TMs are required for proper function (35). Therefore, the finding that the entire C-terminal TM segment of MdfA is not essential for expression and function is surprising and unique among other MFS-related transporters. To our knowledge, among transport proteins in general, only the ABC-related Mdr transporter Cdr1p from Candida albicans was shown to be functional in the absence of its TM12 (14).

Although TM12 of MdfA is clearly nonessential, it is noteworthy that its truncation has remarkable influence not only on the level of resistance, but also on the substrate recognition spectrum. In a reproducible manner, N11 was able to confer a substantial level of resistance to EtBr, benzalkonium, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol. Interestingly, however, the truncation of TM12 abolishes the ability of MdfA to confer resistance to puromycin, TPP+, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin, all of which are poor substrates of MdfA. Although this effect might be similar to that observed with Cdr1p, where the truncation of TM12 also resulted in an alteration in drug specificity (14), it seems more likely that the selective loss of drug resistance, as mediated by N11, might reflect its very low activity.

In any case, it seems that fusing a polypeptide at the C terminus of N11 has an interesting effect on function. Although both N11 and the hybrid N11-PhoA are biologically active, they exhibit different drug resistance patterns. Whereas N11-PhoA confers higher resistance to EtBr, the truncated mutant N11 confers higher resistance to chloramphenicol. Intuitively, the PhoA moiety might affect the conformation of N11 in such a way that it better recognizes EtBr than chloramphenicol. A related phenomenon has been described recently with circularly permuted variants of the glucose transporter (IICBGlc), which mediates the uptake and concomitant phosphorylation of glucose (1). The fusion of PhoA to periplasmic segments of IICBGlc increased glucose transport activities. However, for some of these mutants, the glucose phosphotransferase activity was decreased upon the fusion of the PhoA moiety (1).

In summary, our results suggest that, although not absolutely essential, the domain containing the C-terminal TM and the cytoplasmic tail of MdfA might be important for maintaining the fully functional conformation of the transporter. This conclusion is supported by our recent findings that mutations in this domain do change the transport properties of MdfA (J. Adler and E. Bibi, unpublished results).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Y. Leon Benoziyo Institute for Molecular Medicine at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beutler, R., F. Ruggiero, and B. Erni. 2000. Folding and activity of circularly permuted forms of a polytopic membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1477-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibi, E., and O. Béjà. 1994. Membrane topology of multidrug resistance protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19910-19915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibi, E., J. Adler, O. Lewinson, and R. Edgar. 2001. MdfA, an interesting model protein for studying multidrug transport. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:171-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibi, E., P. Gros, and H. R. Kaback. 1993. Functional expression of mouse multidrug resistance protein in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9209-9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolhuis, H., H. W. van Veen, J. R. Brands, M. Putman, B. Poolman, A. J. M. Driessen, and N. W. Konings. 1996. Energetics and mechanism of drug transport mediated by the lactococcal multidrug transporter LmrP. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24123-24128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botfield, M., and T. Wilson. 1989. Carboxy-terminal truncations of the melibiose carrier of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 264:11643-11648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, D., B. Traxler, and J. Beckwith. 1993. Analysis of the topology of a membrane protein by using a minimum number of alkaline phosphatase fusions. J. Bacteriol. 175:553-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brickman, E., and J. Beckwith. 1975. Analysis of the regulation of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase synthesis using deletions and phi80 transducing phages. J. Mol. Biol. 96:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calamia, J., and C. Manoil. 1992. Membrane protein spanning segments as export signals J. Mol. Biol. 224:539-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edgar, R., and E. Bibi. 1997. MdfA, an Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein with an extraordinarily broad spectrum of drug recognition. J. Bacteriol. 179:2274-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar, R., and E. Bibi. 1999. A single membrane-embedded negative charge is critical for recognizing positively charged drugs by the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein MdfA. EMBO J. 18:822-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinius, L., G. Dreguniene, E. B. Goldberg, C. H. Liao, and S. J. Projan. 1992. A staphylococcal multidrug resistance gene product is a member of a new protein family. Plasmid 27:119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirata, T., E. Fujihira, T. Kimura-Someya, and A. Yamaguchi. 1998. Membrane topology of the staphylococcal tetracycline efflux protein Tet(K) determined by antibacterial resistance gene fusion. J. Biochem. 124:1206-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnamurthy, S., U. Chatterjee, V. Gupta, R. Prasad, P. Das, P. Snehlata, S. E. Hasnain, and R. Prasad. 1998. Deletion of transmembrane domain 12 of CDR1, a multidrug transporter from Candida albicans, leads to altered drug specificity: expression of a yeast multidrug transporter in baculovirus expression system. Yeast 14:535-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, C., P. Li, H. Inouye, E. R. Brickman, and J. Beckwith. 1989. Genetic studies on the inability of β-galactosidase to be translocated across the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic membrane. J. Bacteriol. 171:4609-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy, S. B. 1992. Active efflux mechanisms for antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:695-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinson, O., and E. Bibi. 2001. Evidence for simultaneous binding of dissimilar substrates by the Escherichia coli multidrug transporter MdfA. Biochemistry 40:12612-12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis, K. 1994. Multidrug resistance pumps in bacteria: variations on a theme. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis, K., V. Naroditskaya, A. Ferrante, and I. Fokina. 1994. Bacterial resistance to uncouplers. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 20:639-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, X. Z., D. Ma, D. M. Livermore, and H. Nikaido. 1994. Role of efflux pump(s) in intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: active efflux as a contributing factor to beta-lactam resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1742-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlejohn, T. G., I. T. Paulsen, M. T. Gillespie, J. M. Tennent, M. Midgley, I. G. Jones, A. S. Purewal, and R. A. Skurray. 1992. Substrate specificity and energetics of antiseptic and disinfectant resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 15:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manoil, C., and J. Beckwith. 1985. TnphoA: a probe for protein export signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:8129-8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markham, P. N., and A. A. Neyfakh. 2001. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr Opin. Microbiol. 4:509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna, E., D. Hardy, and H. R. Kaback. 1992. Evidence that the final turn of the last transmembrane helix in the lactose permease is required for folding. J. Biol. Chem. 267:6471-6474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna, E., D. Hardy, J. C. Pastore, and H. R. Kaback. 1991. Sequential truncation of the lactose permease over a three amino-acid sequence near the carboxyl terminus leads to progressive loss of activity and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2969-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mine, T., Y. Morita, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1998. Evidence for chloramphenicol/H+ antiport in Cmr (MdfA) system of Escherichia coli and properties of the antiporter. J. Biochem. 124:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikaido, H. 1998. Multiple antibiotic resistance and efflux. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:516-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsen, I. W., I. Bakke, A. Vader, Ø. Olsvik, and M. R. El-Gewely. 1996. Isolation of cmr, a novel Escherichia coli chloramphenicol resistance gene encoding a putative efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 178:3188-3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parkhill, J., B. W. Wren, N. R. Thomson, R. W. Titball, M. T. Holden, M. B. Prentice, M. Sebaihia, K. D. James, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. Baker, D. Basham, S. D. Bentley, K. Brooks, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, R. M. Davies, P. Davis, G. Dougan, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. V. Karlyshev, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. C. Oyston, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature 413:523-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkhill, J., G. Dougan, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, D. Pickard, J. Wain, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. T. Holden, M. Sebaihia, S. Baker, D. Basham, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, P. Connerton, A. Cronin, P. Davis, R. M. Davies, L. Dowd, N. White, J. Farrar, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, A. Haque, T. T. Hien, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, T. S. Larsen, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. O'Gaora, C. Parry, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413:848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulsen, I. T., and R. A. Skurray. 1993. Topology, structure and evolution of two families of proteins involved in antibiotic and antiseptic resistance in eukaryotes and prokaryotes—an analysis. Gene 124:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, and R. A. Skurray. 1996. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol. Rev. 60:575-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, T. G. Littlejohn, B. A. Mitchell, and R. A. Skurray. 1996. Multidrug resistance proteins QacA and QacB from Staphylococcus aureus: membrane topology and identification of residues involved in substrate specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3630-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole, K. 2001. Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:500-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roepe, P. D., R. I. S. Zbar, H. Sarkar, and H. R. Kaback. 1989. A five-residue near the carboxy terminus of the polytopic membrane protein Lac permease is required for stability within the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3992-3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato, K., M. Sato, A. Yamaguchi, and M. Yoshida. 1994. Tetracycline/H+ antiporter was degraded rapidly in Escherichia coli cells when truncated at last transmembrane helix and this degradation was protected by overproduced GroEL/ES. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202:258-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Heijne, G. 1992. Membrane protein structure prediction, hydrophobicity analysis and the positive inside rule. J. Mol. Biol. 255:487-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yerushalmi, H., and S. Schuldiner. 2000. An essential glutamyl residue in EmrE, a multidrug antiporter from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5264-5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zelazny, A., and E. Bibi. 1996. Biogenesis and topology of integral membrane proteins: characterization of lactose permease-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase hybrids. Biochemistry 35:10872-10878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]