Abstract

1. Thermal stimulation of frog skin produces a discharge in afferents in the dorsocutaneous nerve. The characteristics of this response have been examined with regard to static and dynamic sensitivity to thermal stimuli and to mechanical sensitivity. Frog cutaneous receptors respond only to cooling, with no response to warming through the same thermal range.

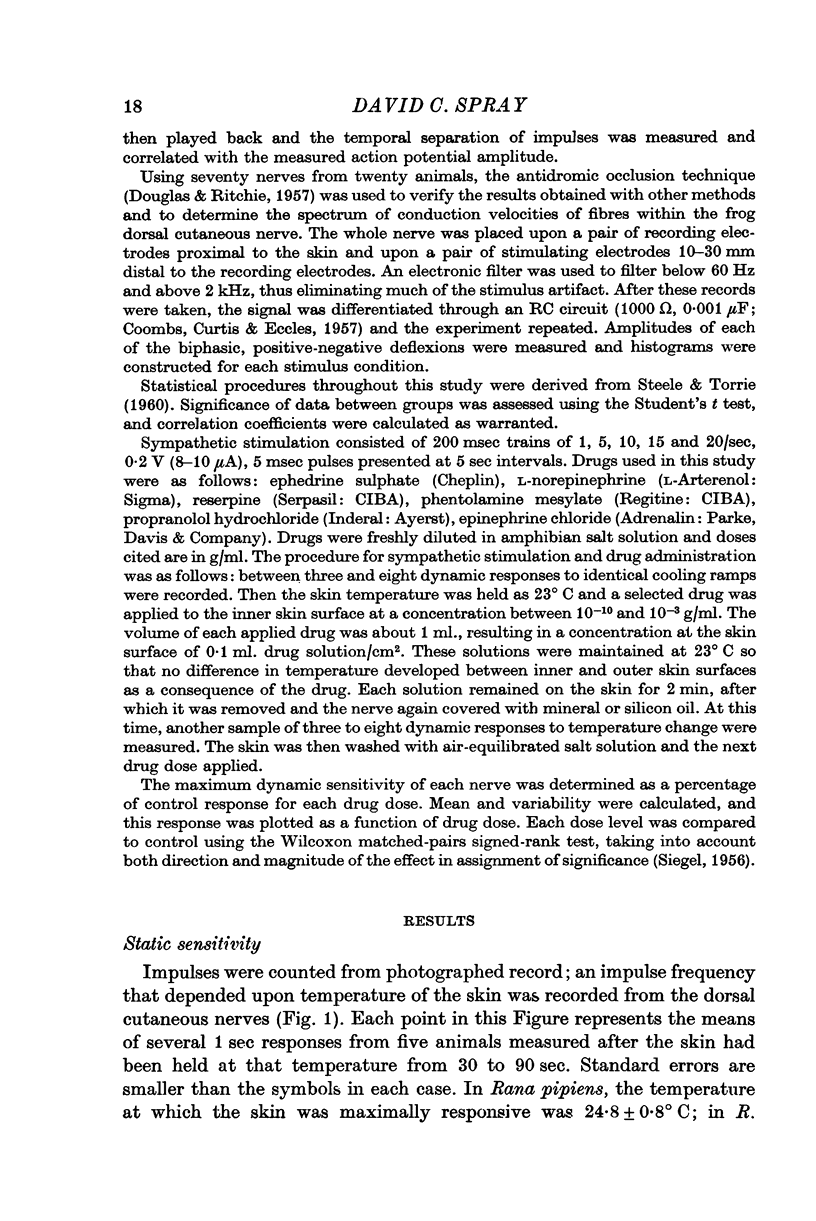

2. The static temperature at which these receptors are maximally active is about 24° C for Rana pipiens and about 27° C for R. catesbiana.

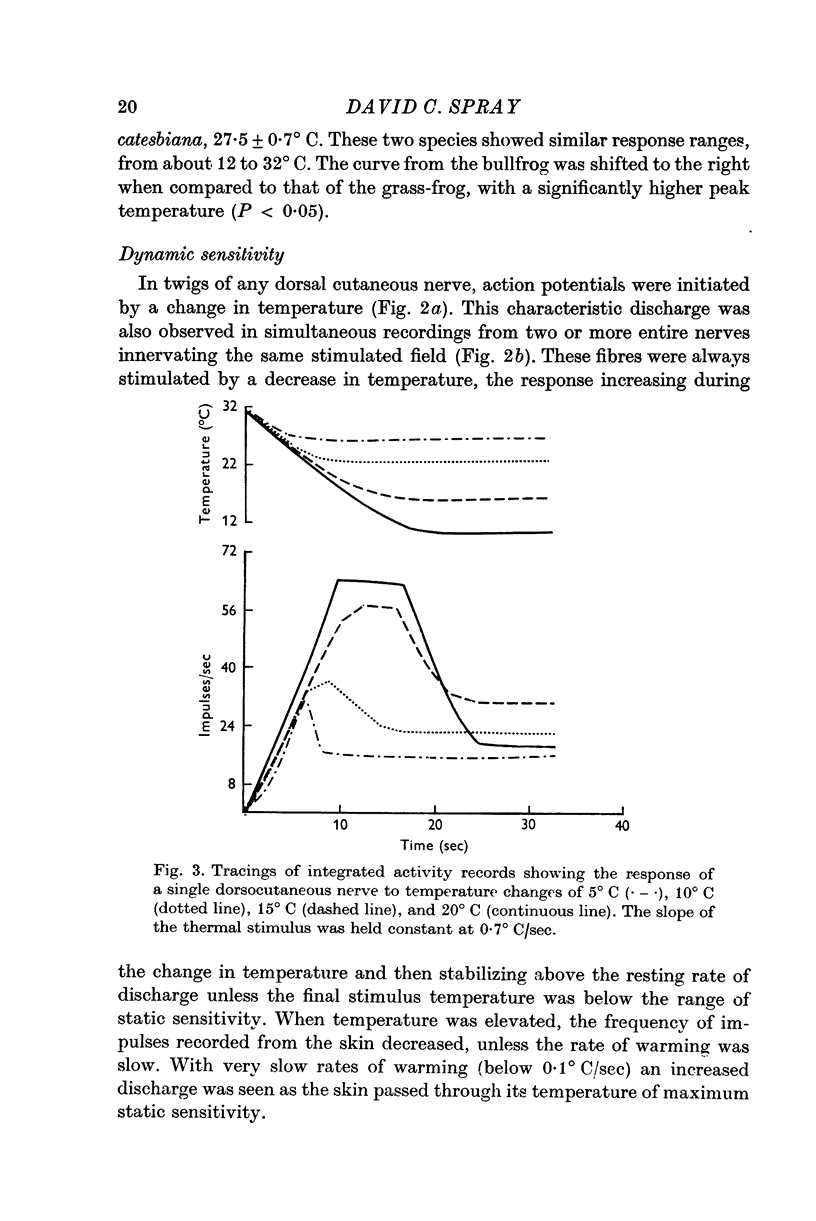

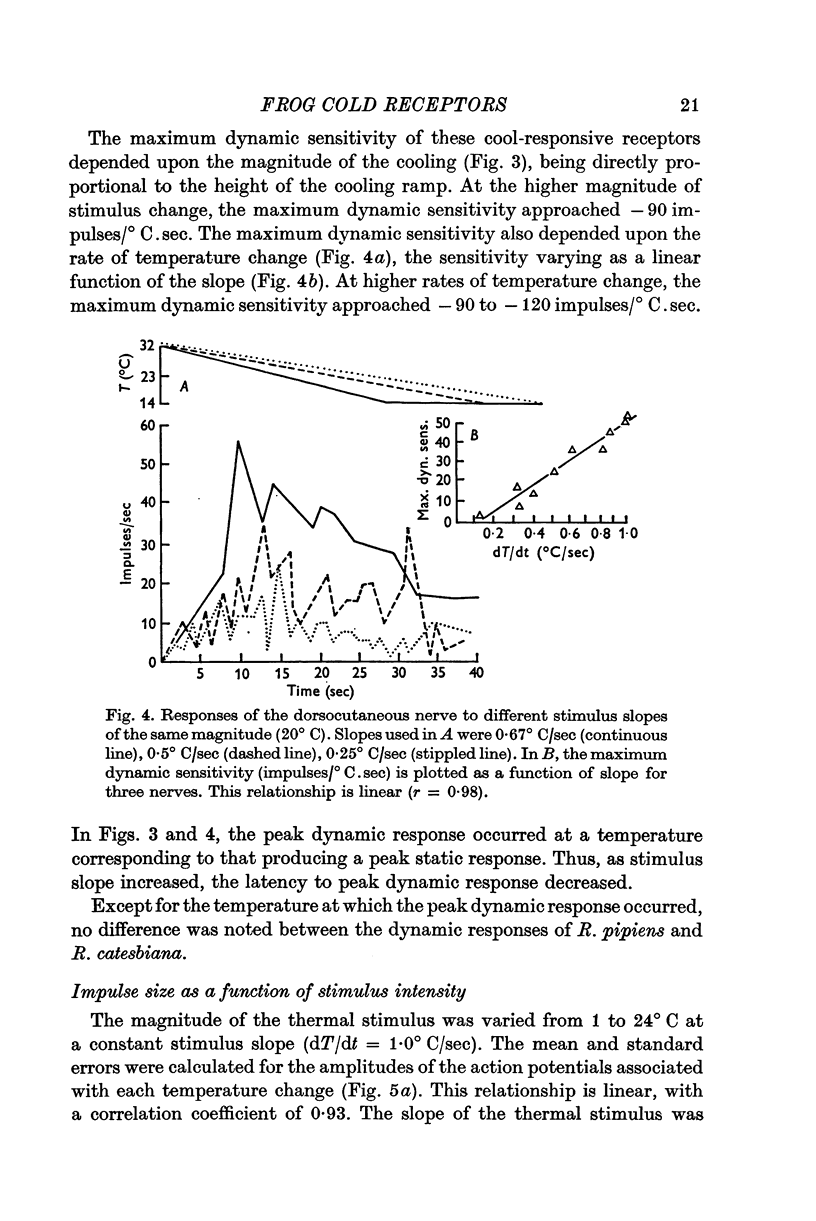

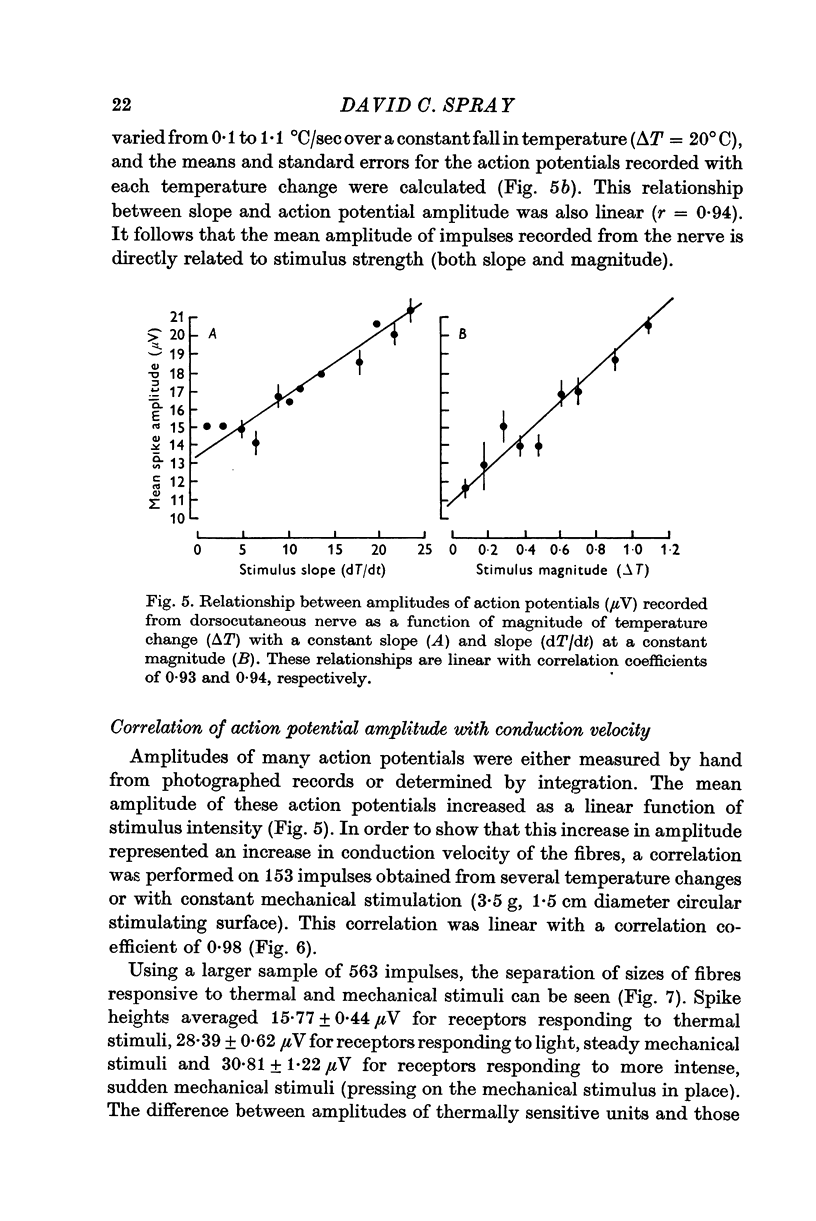

3. The dynamic sensitivity of frog cutaneous receptors is linearly related to both stimulus slope and magnitude. Maximum dynamic sensitivity was between -90 and -120 impulses/° C.sec.

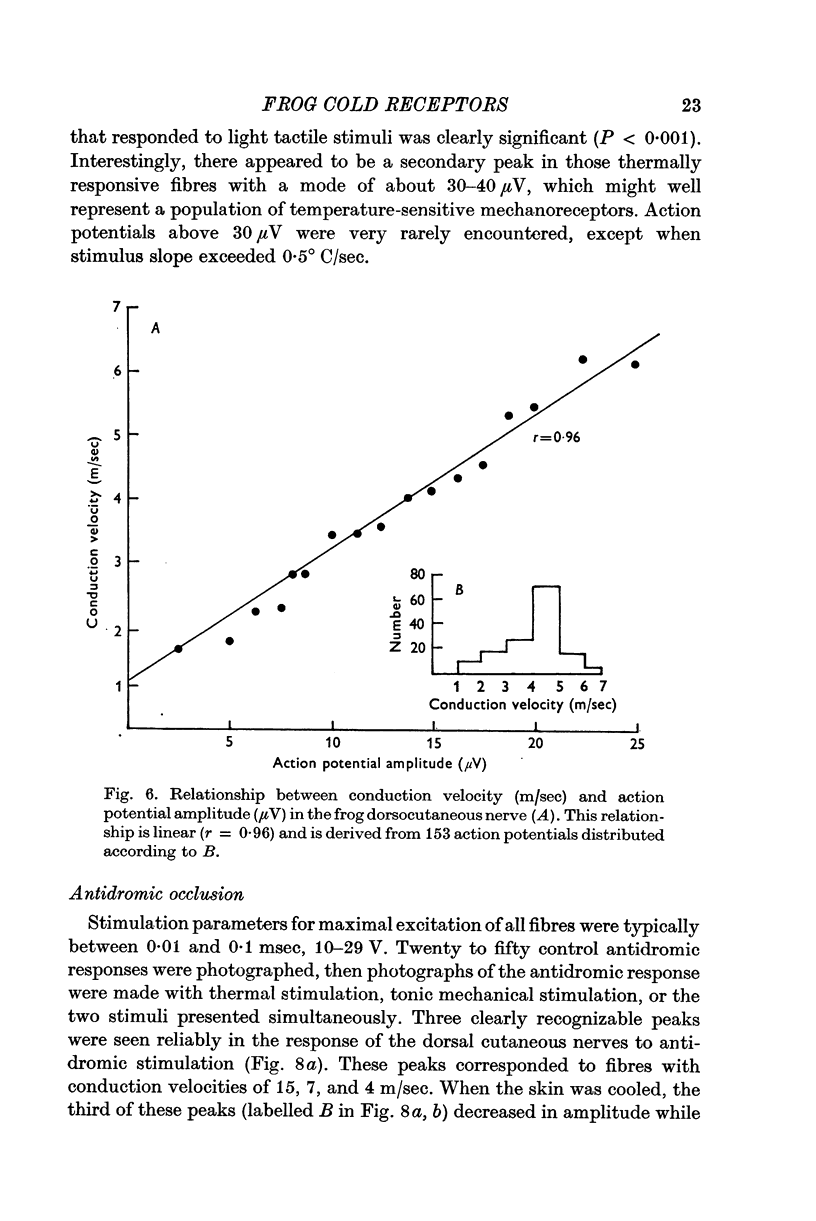

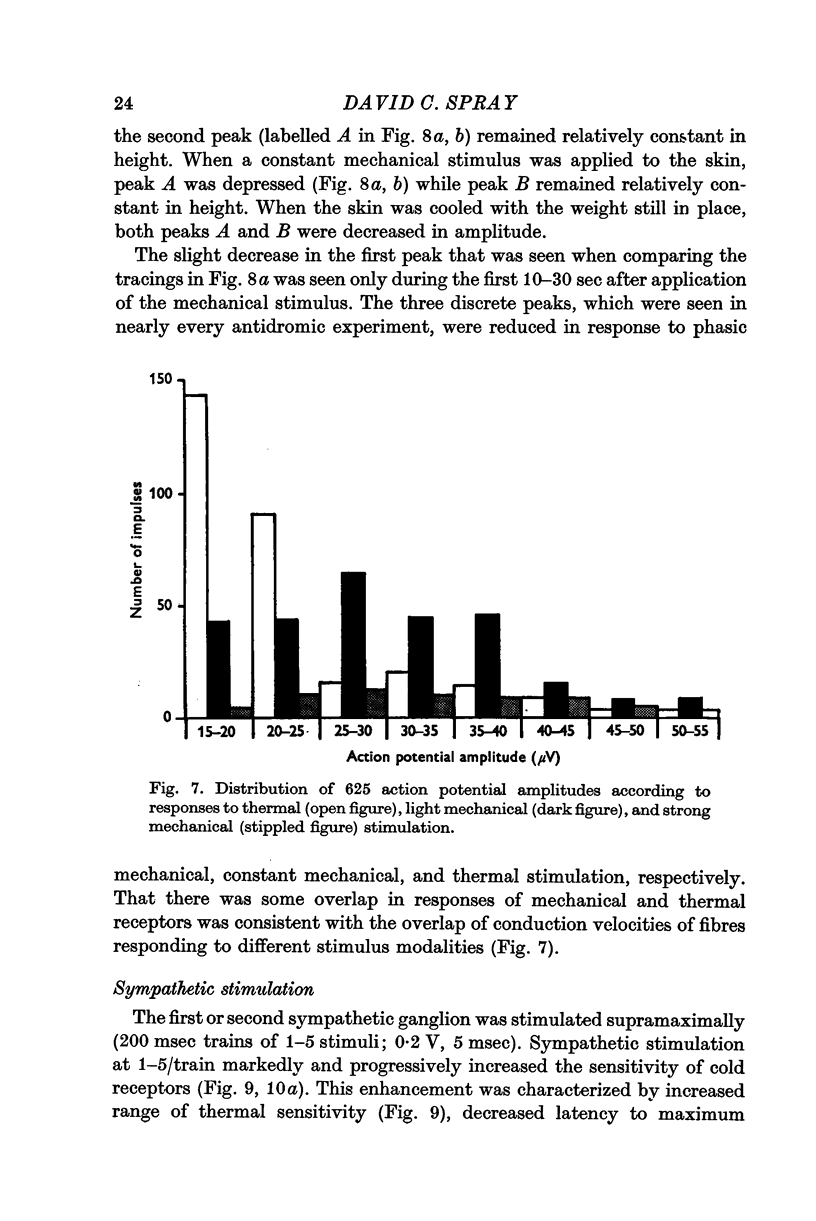

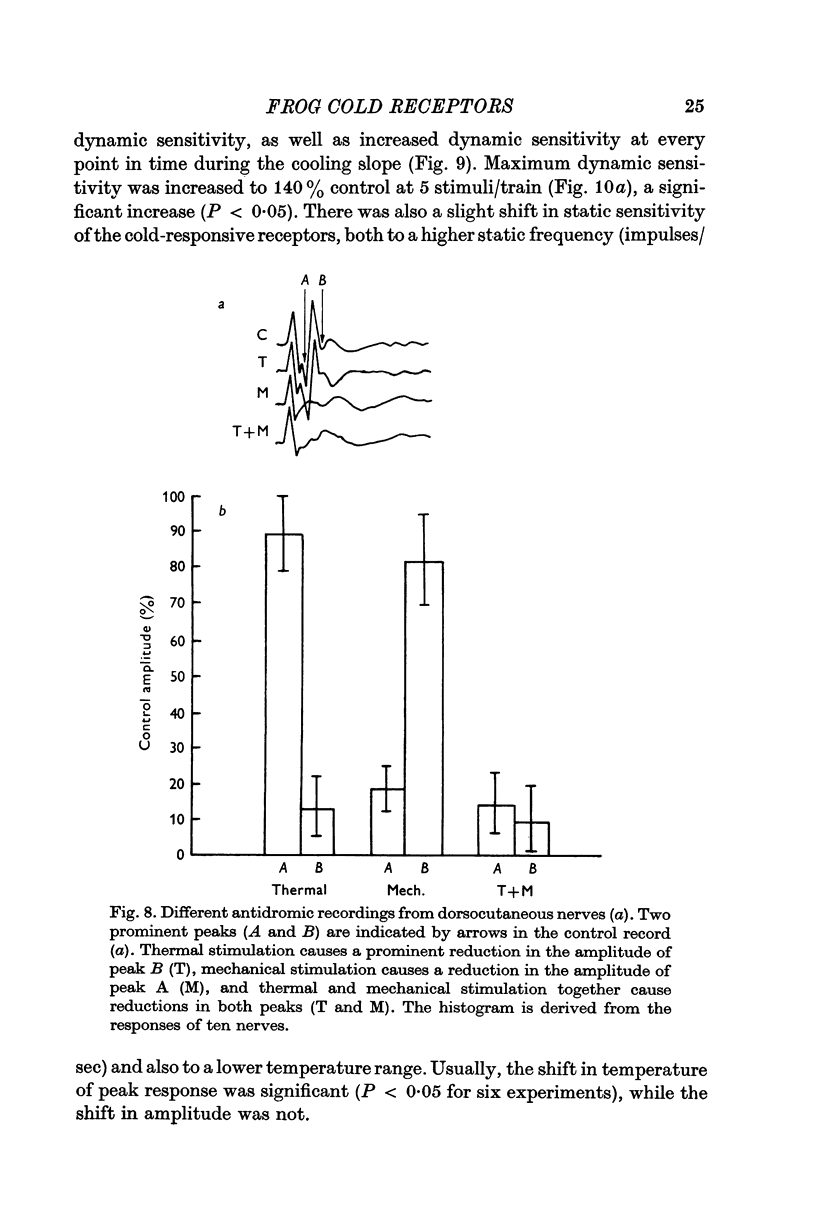

4. Antidromic occlusion experiments demonstrate relative insensitivity of these receptors to tonic mechanical stimulation. At high stimulus intensities, however, larger fibres are recruited into the response; this recruitment of action potentials of larger amplitude is a linear function of both stimulus slope and magnitude.

5. Spike heights are linearly related to conduction velocities in the dorsocutaneous nerve; tonic mechanoreceptors have a mean spike height of 28·4±0·6 μV and conduction velocities about 6-8 m/sec, whereas these temperature sensitive receptors have spike heights 15·8±0·4 μV and conduction velocities about 3-4 m/sec.

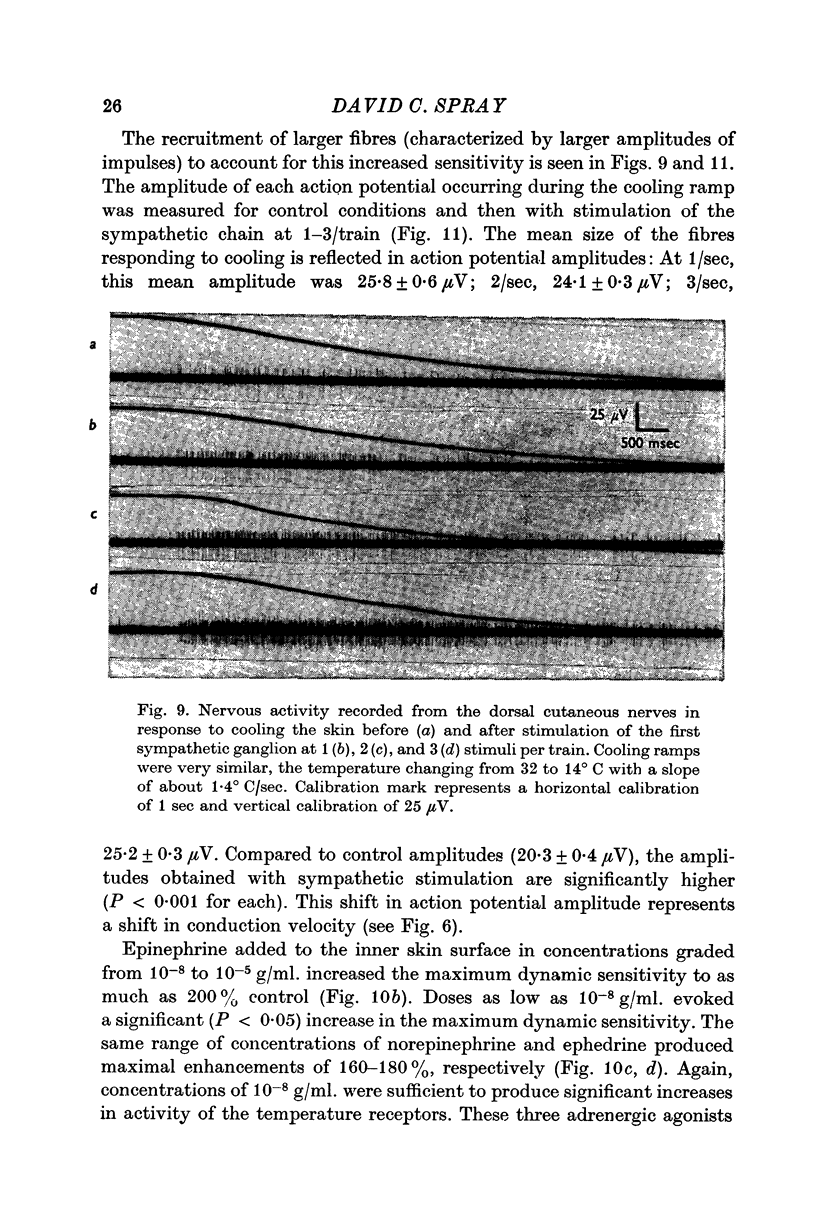

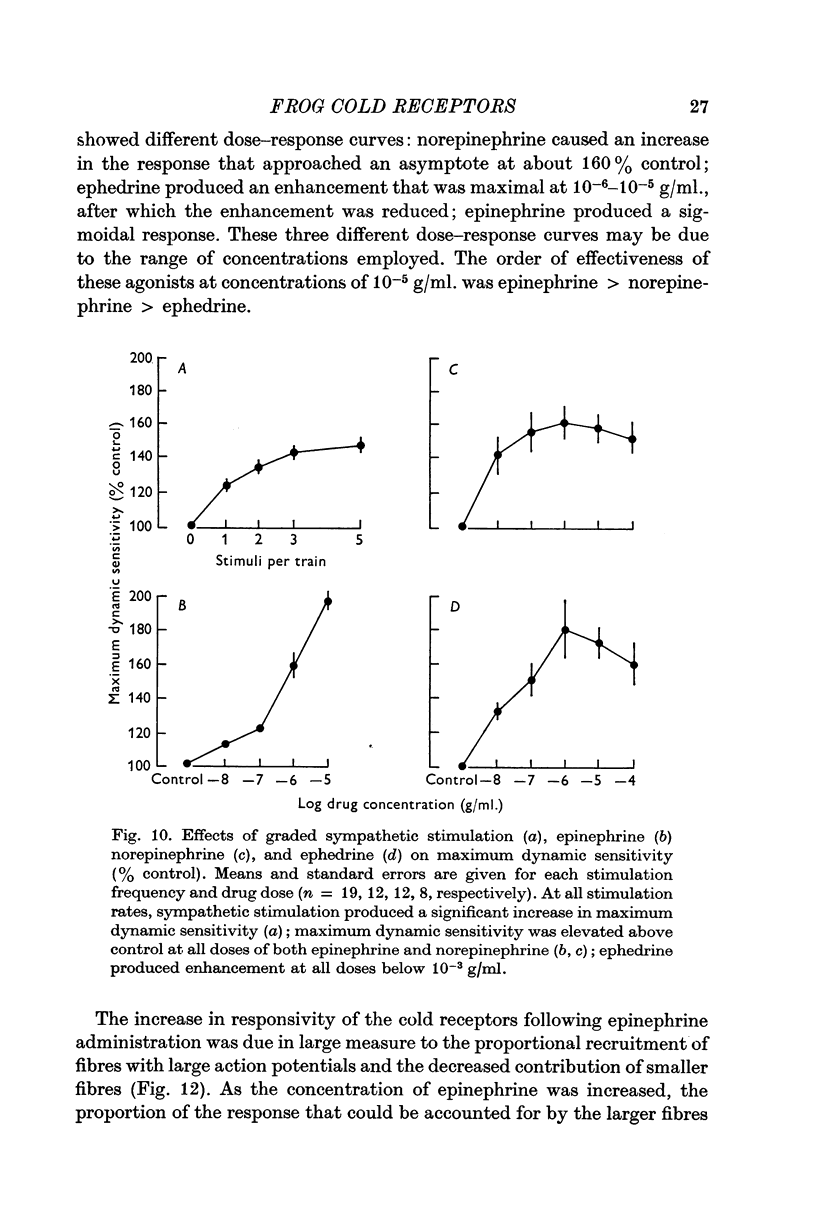

6. Maximum dynamic sensitivity skin is increased following stimulation of the first or second sympathetic ganglion. This increase is both marked and progressive, reaching a maximal enhancement of about 150-160% control at a stimulus rate of 5 stimuli/train, each train delivered once every 5 sec.

7. Static sensitivity of the cold receptors is also increased following sympathetic stimulation. This increased sensitivity is shown by both increased discharge rate within the same thermal range and by decreased temperature of maximum static sensitivity.

8. Sympathetic modulation of dynamic thermal sensitivity is mimicked by epinephrine and norepinephrine in doses of 10-6-10-7 g/ml. Ephedrine, another adrenergic agonist, also mimics the enhancement of cold receptors by sympathetic stimulation.

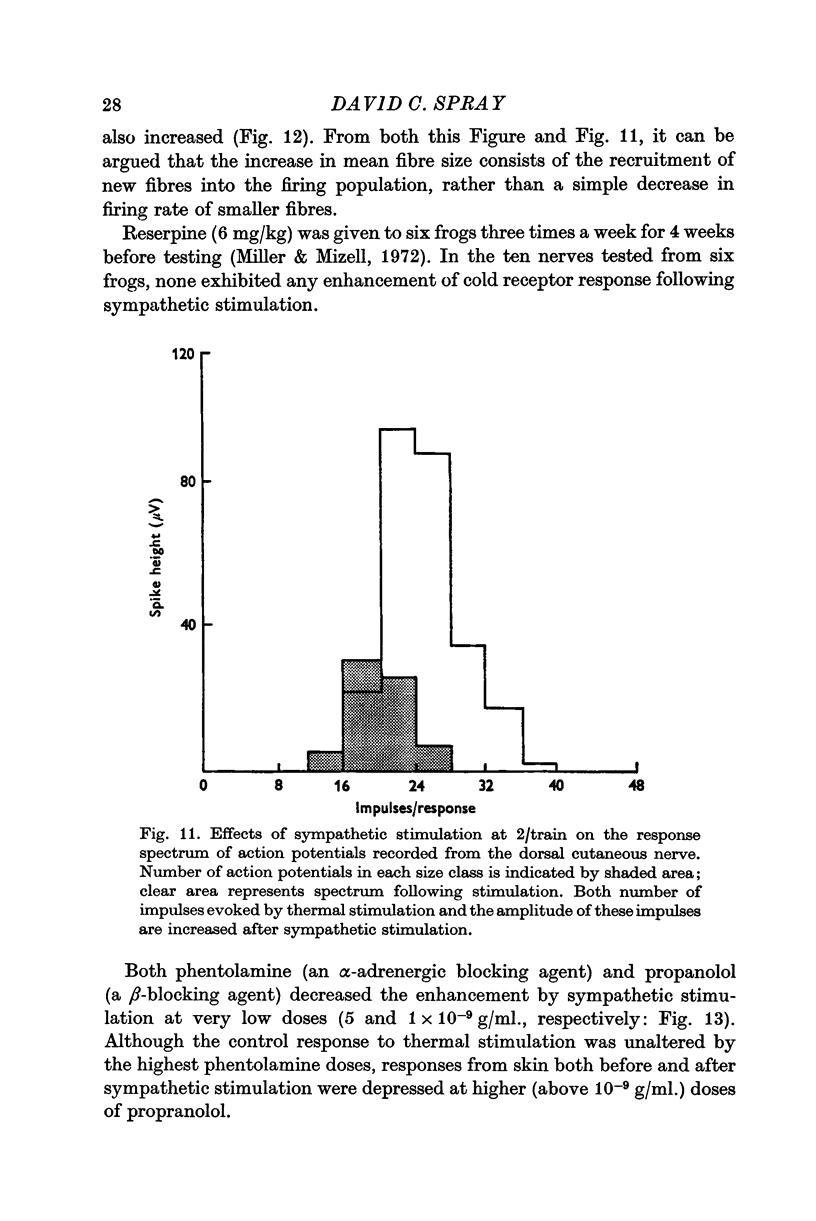

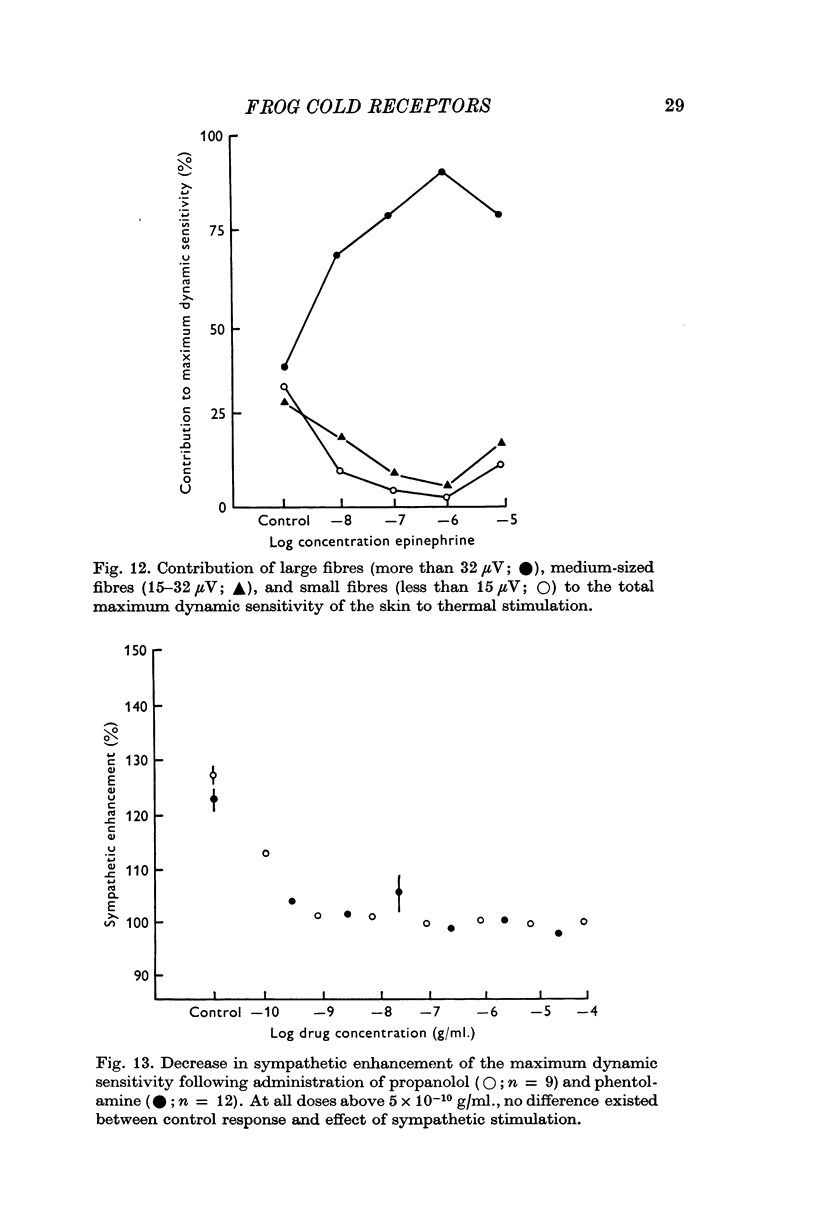

9. Larger fibres are recruited to account for the increased sensitivity of thermoreceptors following sympathetic stimulation and epinephrine application.

10. Propranolol and phentolamine both block the enhancement of the response by sympathetic stimulation, but propranolol blocks the response of the receptor to thermal stimulation as well. Reserpine pre-treatment blocks the effect of sympathetic stimulation on the cold response.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALTAMIRANO-ORREGO R., LOEWENSTEIN W. R. Enhancement of activity in a Pacinian corpuscle by sympathomimetic agents. Nature. 1956 Dec 8;178(4545):1292–1293. doi: 10.1038/1781292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T., Binia A., Visscher M. B. Adrenergic mechanisms in the bullfrog and turtle. Am J Physiol. 1965 Dec;209(6):1287–1294. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.209.6.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEIDLER L. M. Properties of chemoreceptors of tongue of rat. J Neurophysiol. 1953 Nov;16(6):595–607. doi: 10.1152/jn.1953.16.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOMAN K. K. Elektrophysiologische Untersuchungen über die Thermoreceptoren der Gesichtshaut. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1958;44(149):1–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BULLOCK T. H. Comparative aspects of some biological transducers. Fed Proc. 1953 Sep;12(3):666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing H., Hensel H., Wurster R. Integrated static acitivity of lingual cold receptors. Pflugers Arch. 1969;311(1):50–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00588061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J. Carotid body: structure and function. Physiol Rev. 1971 Jul;51(3):437–495. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1971.51.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H., Terashima S. I., Clark J. Response properties of slowly adapting mechanoreceptors to temperature stimulation in cats. Brain Res. 1972 Oct 27;45(2):401–416. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATTON W. T. Some properties of frog skin mechanoreceptors. J Physiol. 1958 Apr 30;141(2):305–322. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp005975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERNETSKI K. E. SYMPATHETIC ENHANCEMENT OF PERIPHERAL SENSORY INPUT IN THE FROG. J Neurophysiol. 1964 May;27:493–515. doi: 10.1152/jn.1964.27.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOMBS J. S., CURTIS D. R., ECCLES J. C. The generation of impulses in motoneurones. J Physiol. 1957 Dec 3;139(2):232–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS D. R. The pharmacology of central and peripheral inhibition. Pharmacol Rev. 1963 Jun;15:333–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON W. W. THERMAL STIMULATION OF EXPERIMENTALLY VASOCONSTRICTED HUMAN SKIN. Percept Mot Skills. 1964 Dec;19:775–788. doi: 10.2466/pms.1964.19.3.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DODT E. Schmerzimpulse bei Temperaturreizen. Acta Physiol Scand. 1954 Jun 21;31(1):83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1954.tb01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DODT E., WALTHER J. B. Wirkungen zentrifugaler Nervenreizung auf Thermoreceptoren. Pflugers Arch. 1957;265(4):355–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00364186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS W. W., GRAY J. A. B. The excitant action of acetylcholine and other substances on cutaneous sensory pathways and its prevention by hexamethonium and D-tubocurarine. J Physiol. 1953 Jan;119(1):118–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS W. W., RITCHIE J. M. A technique for recording functional activity in specific groups of medullated and non-medullated fibres in whole nerve trunks. J Physiol. 1957 Aug 29;138(1):19–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis W. J. Functional significance of motorneuron size and soma position in swimmeret system of the lobster. J Neurophysiol. 1971 Mar;34(2):274–288. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERLIJ D., CETRANGOLO R., VALADEZ R. ADRENOTROPIC RECEPTORS IN THE FROG. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1965 Jul;149:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R. P. Use of Thin Kidney Slices and Isolated Renal Tubules for Direct Study of Cellular Transport Kinetics. Science. 1948 Jul 16;108(2794):65–67. doi: 10.1126/science.108.2794.65-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENNEMAN E., SOMJEN G., CARPENTER D. O. FUNCTIONAL SIGNIFICANCE OF CELL SIZE IN SPINAL MOTONEURONS. J Neurophysiol. 1965 May;28:560–580. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENSEL H., BOMAN K. K. Afferent impulses in cutaneous sensory nerves in human subjects. J Neurophysiol. 1960 Sep;23:564–578. doi: 10.1152/jn.1960.23.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENSEL H., IGGO A., WITT I. A quantitative study of sensitive cutaneous thermoreceptors with C afferent fibres. J Physiol. 1960 Aug;153:113–126. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENSEL H. The time factor in thermoreceptor excitation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1953 Jun 26;29(1):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1953.tb01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENSEL H., ZOTTERMAN Y. The response of mechanoreceptors to thermal stimulation. J Physiol. 1951 Sep;115(1):16–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNT C. C., McINTYRE A. K. An analysis of fibre diameter and receptor characteristics of myelinated cutaneous afferent fibres in cat. J Physiol. 1960 Aug;153:99–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habgood J. S. Sensitization of sensory receptors in the frog's skin. J Physiol. 1950 Apr 15;111(1-2):195–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1950.sp004474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg B. M. Slow impulses from the cutaneous nerves of the frog. J Physiol. 1935 Jun 18;84(3):250–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1935.sp003273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iggo A. Cutaneous thermoreceptors in primates and sub-primates. J Physiol. 1969 Feb;200(2):403–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENSHALO D. R., NAFE J. P. CUTANEOUS VASCULAR SYSTEM AS A MODEL TEMPERATURE RECEPTOR. Percept Mot Skills. 1963 Aug;17:257–258. doi: 10.2466/pms.1963.17.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOEWENSTEIN W. R. Modulation of cutaneous mechanoreceptors by sympathetic stimulation. J Physiol. 1956 Apr 27;132(1):40–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARUHASHI J., MIZUGUCHI K., TASAKI I. Action currents in single afferent nerve fibres elicited by stimulation of the skin of the toad and the cat. J Physiol. 1952 Jun;117(2):129–151. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. C., Mizell S. Seasonal variation in heart-rate-core temperature relationship in Rana pipiens: the role of the autonomic nervous system. Comp Gen Pharmacol. 1972 Dec;3(12):434–442. doi: 10.1016/0010-4035(72)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson B. Y. Effects of sympathetic stimulation on mechanoreceptors. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972 Jul;85(3):390–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSTLUND E. The distribution of catechol amines in lower animals and their effect on the heart. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1954;31(112):1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAINTAL A. S. EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON VERTEBRATE MECHANORECEPTORS. Pharmacol Rev. 1964 Dec;16:341–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl E. R. Myelinated afferent fibres innervating the primate skin and their response to noxious stimuli. J Physiol. 1968 Aug;197(3):593–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos D. A., Benjamin R. M. Response of thalamic neurons to thermal stimulation of the tongue. J Neurophysiol. 1968 Jan;31(1):28–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos D. A., Lende R. A. Response of trigeminal ganglion neurons to thermal stimulation of oral-facial regions. I. Steady-state response. J Neurophysiol. 1970 Jul;33(4):508–517. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos D. A., Lende R. A. Response of trigeminal ganglion neurons to thermal stimulation of oral-facial regions. II. Temperature change response. J Neurophysiol. 1970 Jul;33(4):518–526. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAJ B. S., MURRAY R. W. Non-myelinated nerves as a model for thermoreceptors. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1962 Apr;5:311–317. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(62)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J. The latent period of skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1932 Jan 14;74(1):17–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1932.sp002825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGURA E. T., D AGOSTINO S. A. SEASONAL VARIATIONS OF BLOOD PRESSURE, VASOMOTOR REACTIVITY AND PLASMATIC CATECHOLAMINES IN THE TOAD. Acta Physiol Lat Am. 1964;14:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALL P. D. Cord cells responding to touch, damage, and temperature of skin. J Neurophysiol. 1960 Mar;23:197–210. doi: 10.1152/jn.1960.23.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]