Abstract

1. Twitch fibres isolated from the sartorius muscle of the frog were glycerinated (cf. Heinl, 1972) and thin fibre bundles dissected from the m. ileofibularis of the tortoise were briefly glycerinated as described by Julian (1971).

2. The glycerinated fibres (length 0·3-0·5 cm) were fixed to an apparatus which performed length changes within 5 msec and recorded the time course of tension changes in the fibres.

3. The fibres were suspended in a relaxing medium, containing ATP and 4 mM-EGTA. Contraction was induced by raising the calcium concentration to 4 mM-CaEGTA.

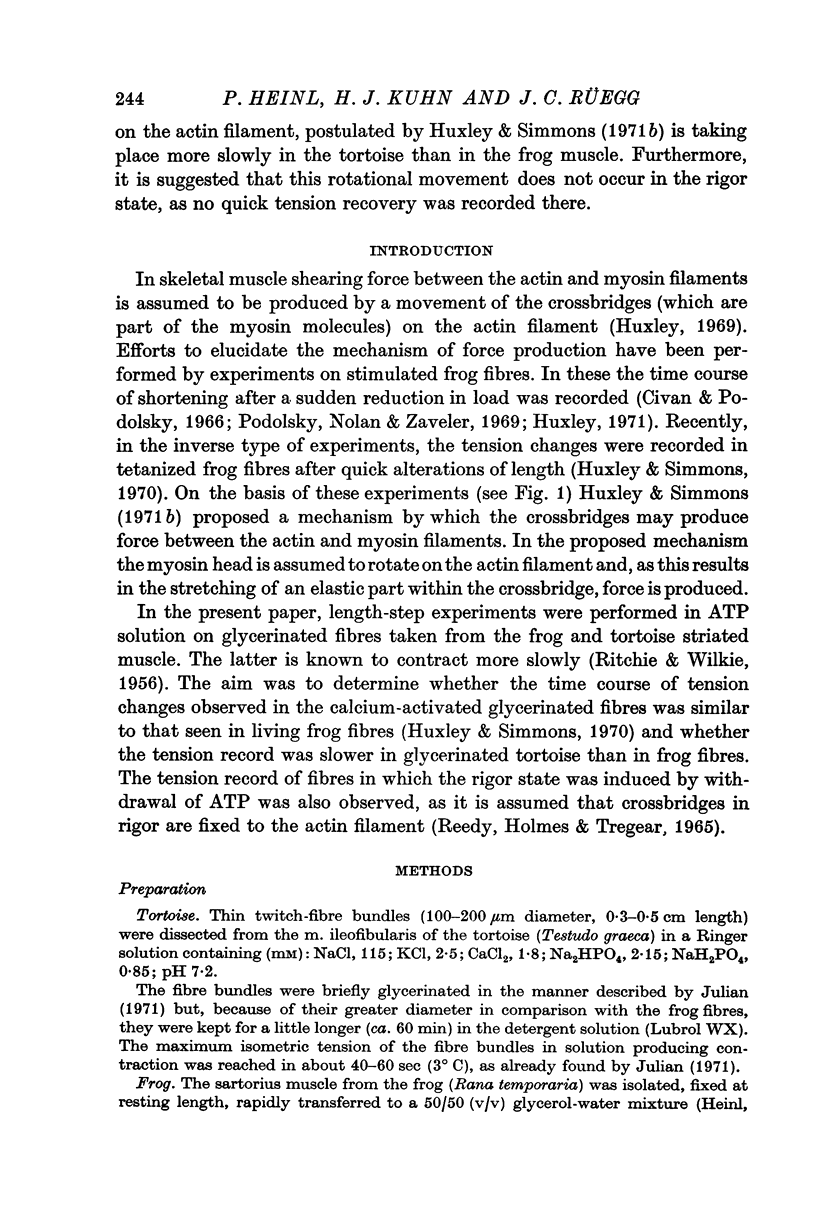

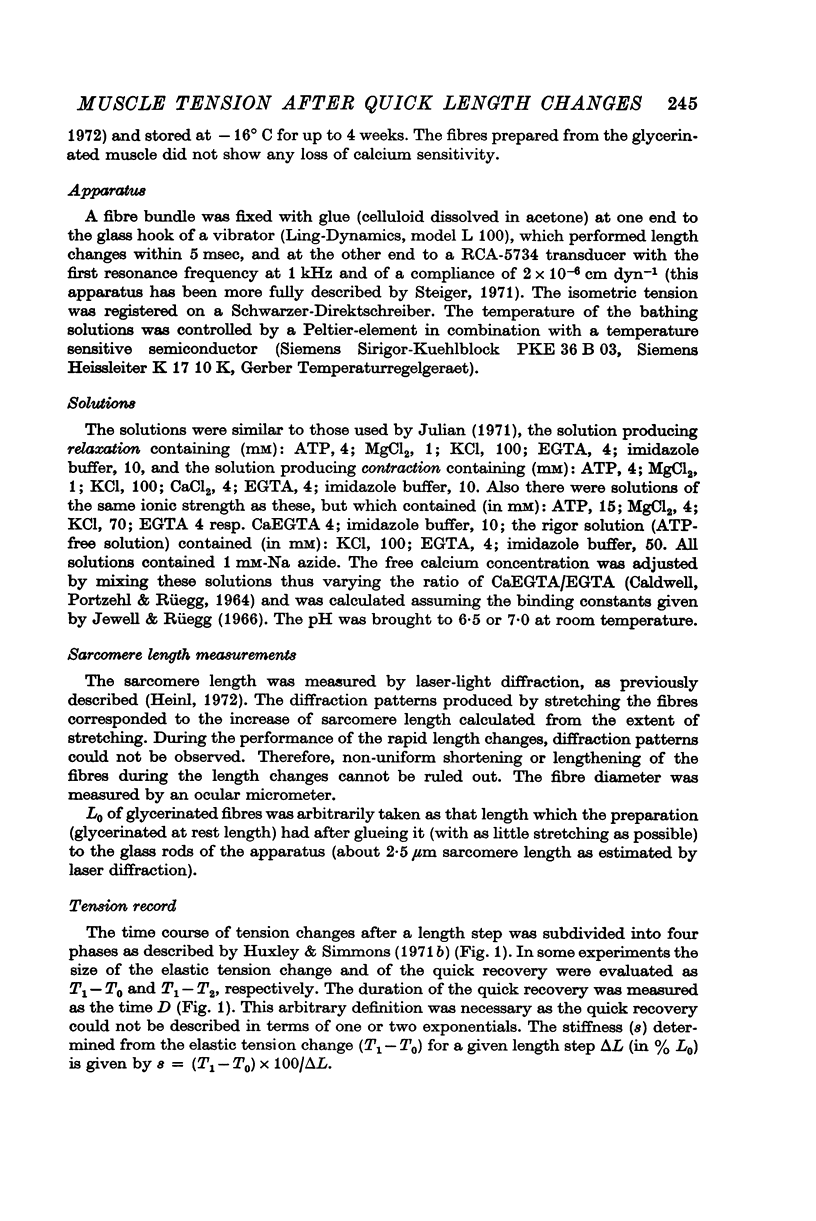

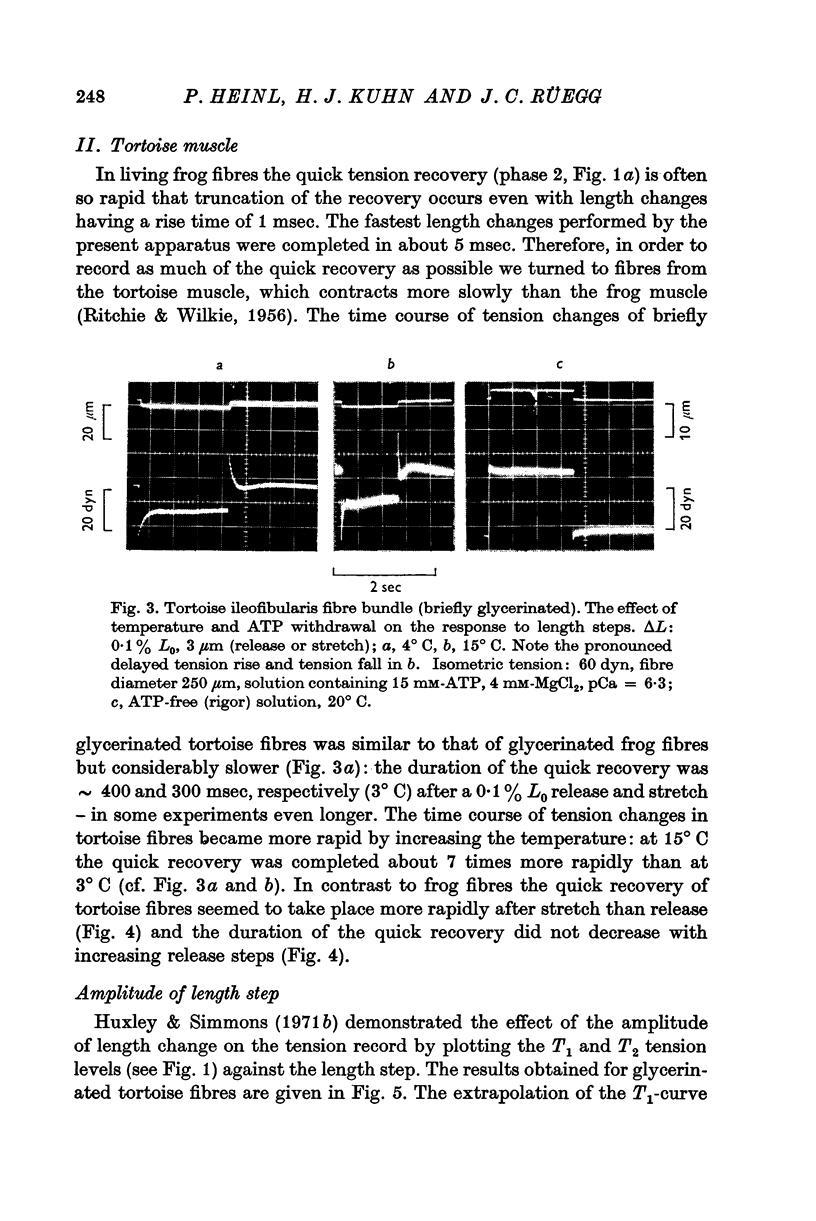

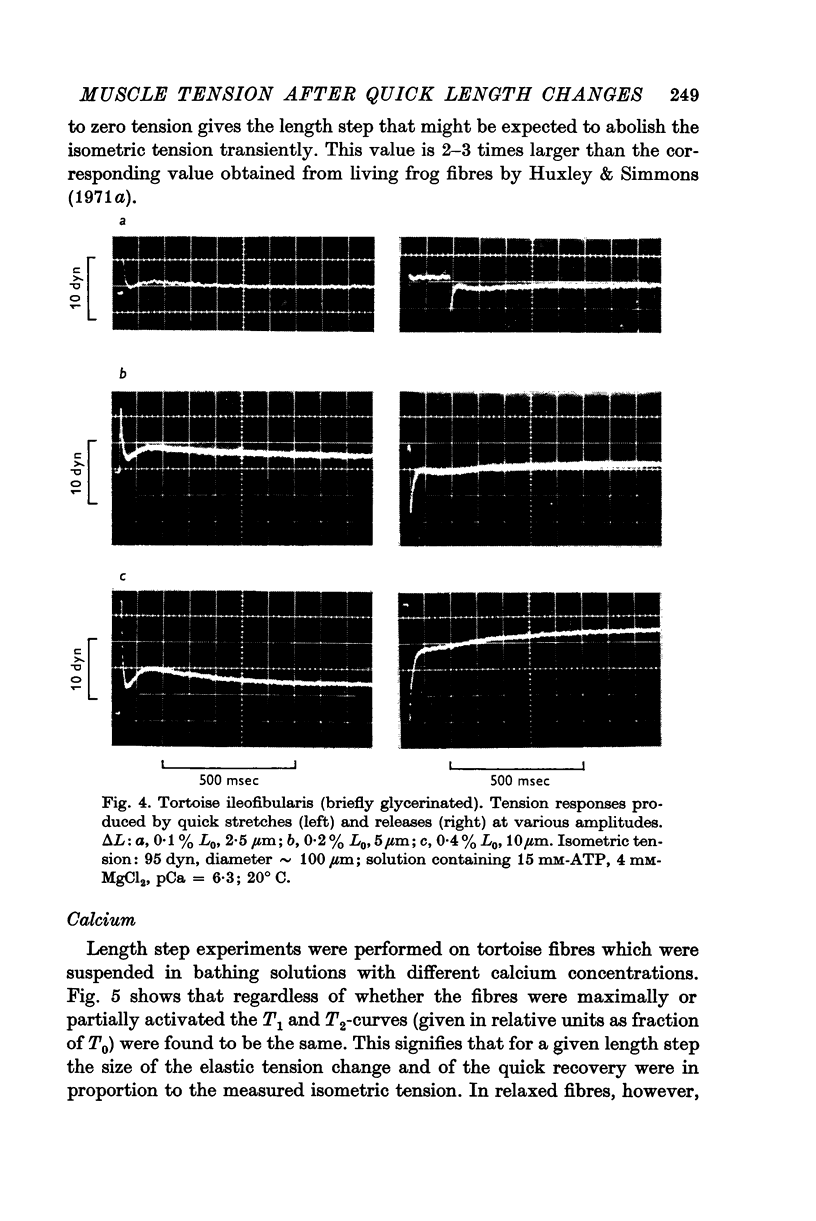

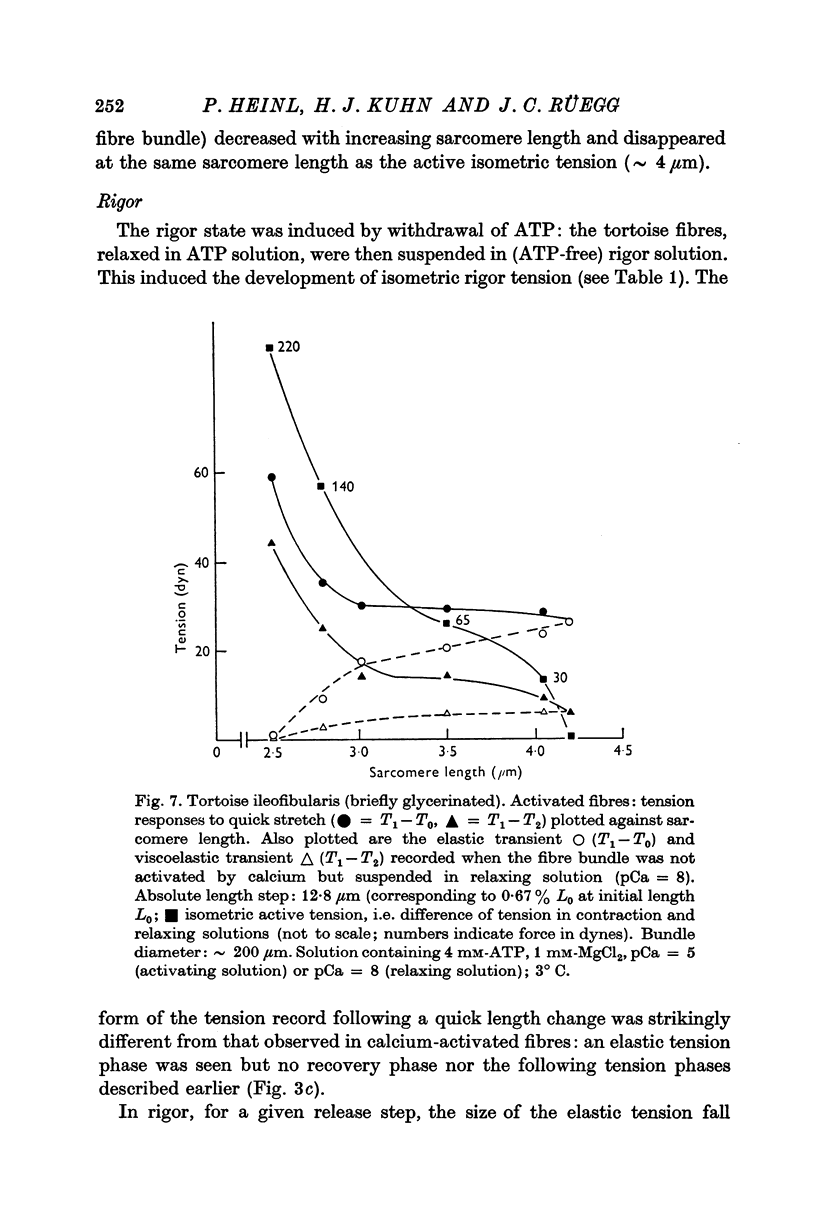

4. The tension time course of activated fibres following quick length changes (0·1-1% L0) was studied. The tension records produced by quick releases and stretches could be resolved into four phases similar to the kind shown in Fig. 1 a.

5. The phase of quick tension recovery was found to take place more rapidly in frog than in tortoise fibres: it was completed in ∼ 30 msec (after stretch) and in ∼ 20 msec (after release) in frog fibres (3° C). The corresponding values obtained for tortoise fibres were ∼ 300 and ∼ 400 msec (3° C).

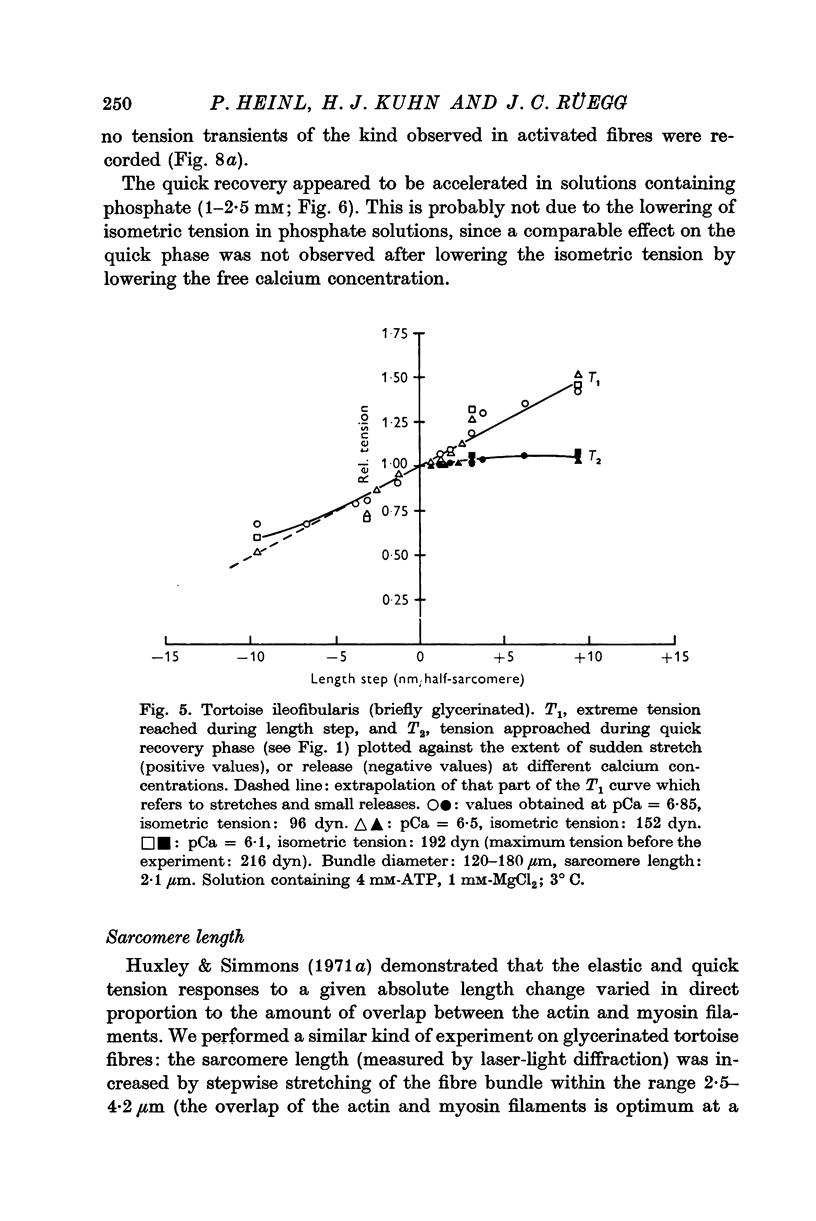

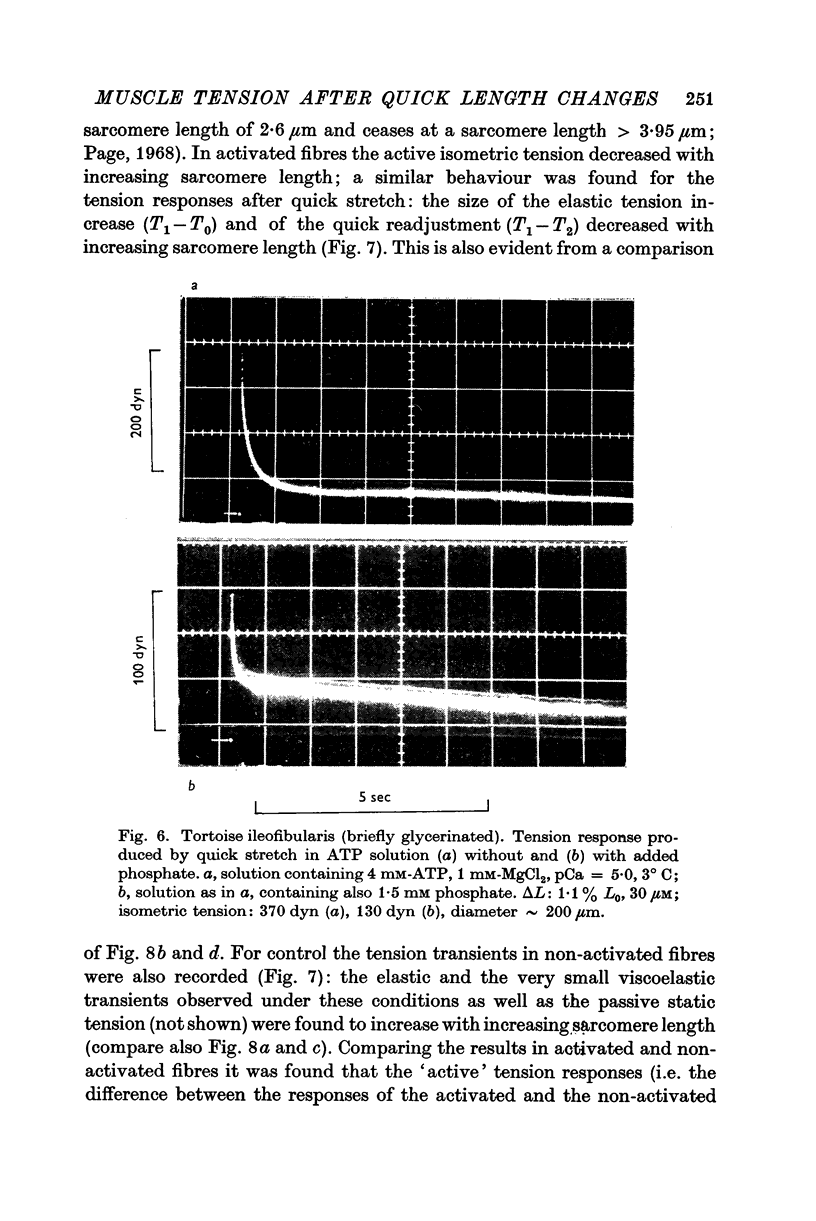

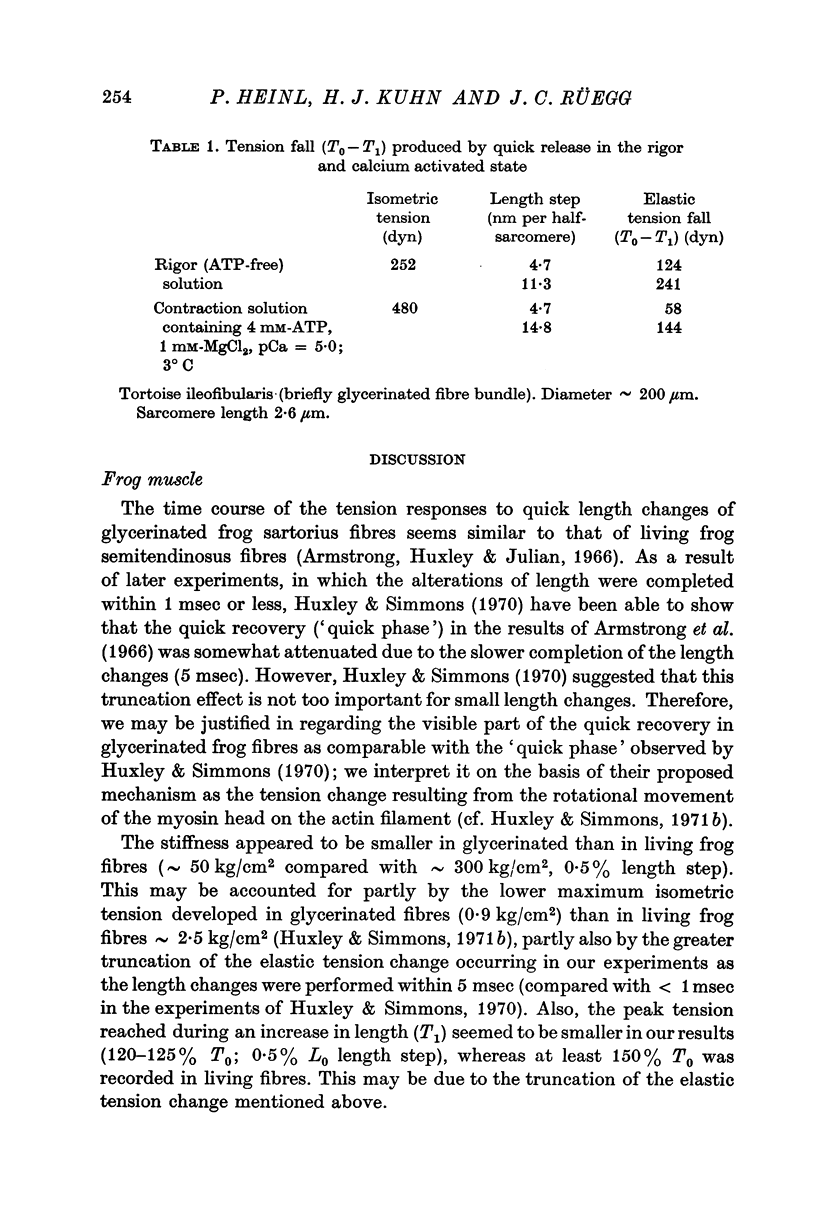

6. In tortoise fibres the size of the elastic and quick recovery phase increased with rising isometric tension (induced by raising the calcium concentration (pCa 8 to 5)), and decreased with increasing sarcomere length (2·5-4·2 μm). In fibres, in which the rigor state was induced by withdrawal of ATP, no quick tension recovery was recorded.

7. It is suggested that the rotational movement of the crossbridge head on the actin filament, postulated by Huxley & Simmons (1971 b) is taking place more slowly in the tortoise than in the frog muscle. Furthermore, it is suggested that this rotational movement does not occur in the rigor state, as no quick tension recovery was recorded there.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Civan M. M., Podolsky R. J. Contraction kinetics of striated muscle fibres following quick changes in load. J Physiol. 1966 Jun;184(3):511–534. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Remedios C. G., Millikan R. G., Morales M. F. Polarization of tryptophan fluorescence from single striated muscle fibers. A molecular probe of contractile state. J Gen Physiol. 1972 Jan;59(1):103–120. doi: 10.1085/jgp.59.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinl P. Mechanische aktivierung und Deaktivierung der isolierten contractilen Struktur des froschsartorius durch rechteckförmige und sinusförmige Längenänderungen. Pflugers Arch. 1972;333(3):213–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00592684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley A. F., Simmons R. M. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature. 1971 Oct 22;233(5321):533–538. doi: 10.1038/233533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley A. F. The activation of striated muscle and its mechanical response. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1971 Jun 15;178(1050):1–27. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1971.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J. The effect of calcium on the force-velocity relation of briefly glycerinated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1971 Oct;218(1):117–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymn R. W., Taylor E. W. Mechanism of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis by actomyosin. Biochemistry. 1971 Dec 7;10(25):4617–4624. doi: 10.1021/bi00801a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTZEHL H., CALDWELL P. C., RUEEGG J. C. THE DEPENDENCE OF CONTRACTION AND RELAXATION OF MUSCLE FIBRES FROM THE CRAB MAIA SQUINADO ON THE INTERNAL CONCENTRATION OF FREE CALCIUM IONS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964 May 25;79:581–591. doi: 10.1016/0926-6577(64)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. G. Fine structure of tortoise skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1968 Aug;197(3):709–715. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky R. J., Nolan A. C., Zaveler S. A. Cross-bridge properties derived from muscle isotonic velocity transients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969 Oct;64(2):504–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.2.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. K., Holmes K. C., Tregear R. T. Induced changes in orientation of the cross-bridges of glycerinated insect flight muscle. Nature. 1965 Sep 18;207(5003):1276–1280. doi: 10.1038/2071276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger G. J. Stretch activation and myogenic oscillation of isolated contractile structures of heart muscle. Pflugers Arch. 1971;330(4):347–361. doi: 10.1007/BF00588586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentham D. R., Bardsley R. G., Eccleston J. F., Weeds A. G. Elementary processes of the magnesium ion-dependent adenosine triphosphatase activity of heavy meromyosin. A transient kinetic approach to the study of kinases and adenosine triphosphatases and a colorimetric inorganic phosphate assay in situ. Biochem J. 1972 Feb;126(3):635–644. doi: 10.1042/bj1260635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]