The third-order NLO materials have attracted considerable attention due to their potential applications including 3-D optical memory and fabrication, optical limiting, and two-photon photo-dynamic therapy.1 Thus, design and synthesis of new molecules with large macroscopic optical nonlinearities represent an active research field in modern chemistry and material science. In general, two-photon absorption (TPA/2PA) is a third-order nonlinear process, and the efficiency of the processes involving two-photon absorption require materials with large absorption cross sections (σ2), which are directly related to the imaginary part of the second hyperpolarizability [Imγ(−ω, ω, ω, −ω)].2 Research on the design and synthesis of such molecules not only requires synthetic skill but also an understanding of structure–property correlation. A handful of reports are available in the literature featuring the design and properties of such compounds.3 Porphyrins are considered suitable for such applications because of the presence of large polarizable conjugated π-electrons required for electronic communication as well as the versatile modifications of the structure possible in the basic framework of the macrocycle skeleton. In fact, TPA in tetrapyrrolic molecules has potential applications for optical power limiting4a and for holographic data storage.4b However, only a limited number of reports of the TPA cross-sections for porphyrins are available in the literature. The majority of regular porphyrins show small σ2 values which typically do not exceed 1–10 GM (1 GM = 10−50 cm4 s photon−1) in the range of near-IR wavelength5 and nearly 100–1600 GM in the Soret band region.6 On the other hand, the σ2 value has been increased up to 50 000 GM in the case of the double-strand conjugated porphyrin polymer,7 whereas intermediate values have been observed in case of conjugated porphyrin dimers8 or triply linked fused porphyrin arrays.9 Thus, the TPA cross-section values given above are orders of magnitude too small for most of the applications mentioned above. Therefore, creating or finding new porphyrin analogues with higher values of σ2 is of practical importance. A well-known fact is that oligothiophenes possess excellent electronic and optical properties;10 for example, α-sexthiophene, the α-linked hexamer of thiophene and its derivatives, has been successfully employed as an active component in organic field-effect transistors and light emitting devices.11 In this context, aromatic core-modified expanded porphyrins where two or four pyrrole rings are replaced by thiophene rings as in 26π hexaphyrin analogues 1 or 34π octaphyrin analogues 2 can be chosen as suitable candidates for satisfying the most necessary and sufficient conditions for an organic material to be NLO active.

Thus, in this paper we wish to report the absolute TPA cross-section values of free base aromatic core-modified 26π hexaphyrin analogues and 34π octaphyrin analogues. TPA cross-sections up to 90 600 GM measured by a femtosecond open-aperture Z-scan method for octaphyrin analogues are among the highest values known for any organic molecules to date. To the best of our knowledge, such types of macrocycles have never been studied for NLO response.

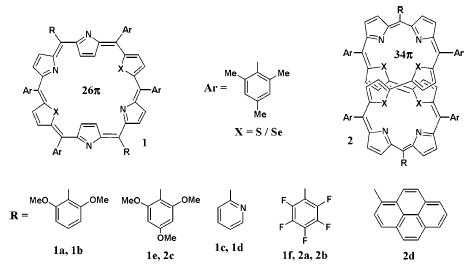

A schematic representation of core-modified expanded porphyrins 1 and 2 under investigation are shown in Chart 1. We have chosen very specifically these macrocycles for a better understanding of the most plausible deciding factors for affecting the σ2 values and hence to know the structure–property correlation by adopting three strategies: (i) the effect of π conjugation, (ii) the effect of core heteroatoms (S vs Se), and (iii) the effect of meso-aryl substituents (electron-releasing vs electron-withdrawing). Following the general synthetic methodologies adopted in our laboratory, the macrocycles 1 and 2 have been achieved via a [3 + 3] or [4 + 4] MacDonald-type acid-catalyzed condensation of appropriate precursors.12 The solid-state structural proof for octaphyrin analogues has been recently obtained by us.12b

Chart 1.

Core-Modified Hexaphyrin and Octaphyrin Analogues

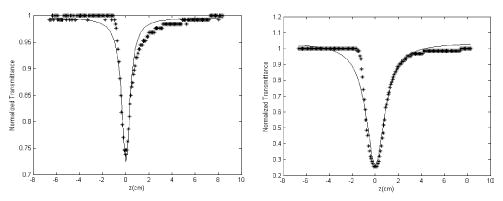

Typically, hexaphyrin analogues exhibit a split Soret-band with λmax 536 nm and the one photon absorption spectral intensity goes to zero level nearly at 780 nm as shown in the inset in Figure 1 for 1f as a representative example.16 On the other hand, octaphyrin analogues exhibit Soret-like absorption at 517 nm and Q-band-like absorption at 671 nm as shown in Figure 2 for 2b.16 Here we would like to mention that the one-photon absorption spectra of the macrocycles 1 and 2 remain invariant with respect to the different meso substituents, and also so far as the effect of core atom on electronic absorption spectra of core modified porphyrins are considered, thiophene and selenophene analogues behave in a similar way.13 Hence, from the UV–vis spectra of these macrocycles, it is clear that all the macrocycles investigated in this work are transparent in the near-infrared region. Thus, nonlinear optical measurements were performed with nonresonant excitation. The TPA cross-section (σ2) values were measured by using a standard open aperture Z-scan technique14 for 1 cm long sample cells. We use 100 fs pulses at 780 nm with 50 MHz repetition rate from Femtolite laser (IMRA) operating at the second-harmonic wavelength of the Er-doped fiber laser. The 20 cm lens used for the Z-scan experiments produce GW-level laser intensities at the focus, which easily induces two-photon absorption (TPA).16 All of the samples were measured at 10−4 M solution in dichloromethane solvent and showed negligible single-photon absorption at 780 nm. The solvent itself does not show any TPA under our experimental conditions. We obtain the observed nonlinear absorption coefficient values (β)9,15 by fitting our measured transmittance values to the following expression: T(z) = 1 − βI0L/[2(1 + z2/z02)], where β = nonlinear absorption coefficient, I0 = on-axis electric field intensity at the focal point in absence of the sample, L = sample thickness, z0 = Rayleigh range (z0 = πw02/λ), where w0 is the minimum spot size at the focal point. The β values are obtained by curve fitting the measured open-aperture traces with the above equation. Figure 1 shows the open aperture traces of 1f and 2b. We have taken rhodamine 6G for which the σ2 value is known15 as the reference for calibrating our measurement technique.16 From the theoretical fits to our experimental results, we find very high TPA cross-section (σ2) values for our conjugated macrocycles.

Figure 1.

Open-aperture Z-scan traces of 1f and 2b. Solid lines are the best-fitted curves of experimental data.

The high values of σ2 observed can be attributed to the extended conjugation effect which is further evident from our observation in an increase in the σ2 values as a function of substituents from electron-releasing to electron-withdrawing groups within the same type of conjugated macrocycles. Moreover, changing the inner heterocyclic rings from thiophene to selenophene provides a marked enhancement in TPA values. The details of these observations are summarized in Table 1. However, as expected from our electron-conjugation argument, a drastic change occurs as we go from 26π to the 34π systems. Furthermore, the 26π hexaphyrin analogues are planar, whereas the 34π octaphyrin analogues are a nonplanar figure-eight configuration; thus, the drastic enhancement in the values of the TPA cross-section in the case of octaphyrin analogues can also be ascribed partly due to the electronic interactions between the two porphyrin like pockets in the basic framework of the macrocycle.

Table 1.

Observed σ2 Values for Macrocycles 1 and 2

| compd | X | σ2 (GM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | S | 2208 |

| 1b | Se | 7800 |

| 1c | S | 3828 |

| 1d | Se | 9060 |

| 1e | S | 4740 |

| 1f | S | 24 000 |

| 2a | S | 81 000 |

| 2b | Se | 90 600 |

| 2c | S | 67 340 |

| 2d | S | 87 694 |

The σ2 values for octaphyrin analogues are enhanced approximately 8–9 (×103) times relative to regular porphyrins clearly showing the effect of extended π-conjugation due to the presence of larger number of π-electrons in octaphyrin analogues (34π vs 18π electrons). The intermediate values obtained in case of porphyrin dimers where two 18π porphyrin units are linked to each other by butadiyne8a or ethynyl linkers8b or are fused together9 have been attributed to strong electronic coupling and the increase in π-conjugation between two monomer units. However, in the expanded porphyrin system the conjugation is much larger in the porphyrin skeleton itself because of the presence of more number of π-electrons relative to dimers.

In conclusion, the aromatic core-modified expanded porphyrins can be attempted as the best suitable candidates especially as organic nonlinear optical materials due to exceptionally large nonresonating two-photon absorption cross-sections. Further studies to exploit these structure–property correlations are currently in progress.

Acknowledgments

T.K.C. thanks DST, New Delhi, India; D.G. thanks DST, MCIT (India) and International SRF Program of Welcome Trust (U.K.) for the financial grant. H.R., J.S., and V.P.R. thank CSIR, India, for their Senior Research Fellowships.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Syntheses and spectroscopic characterization of 1c,e,d,f and 2a–d, UV–vis spectra of 1f and 2b; measurement technique; open aperture Z-scan traces of 1a–e, 2a,c,d, and rhodamine 6G; complete ref 3a. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Ehrlich JE, Wu XL, Lee IY, Hu ZY, Röckel H, Marder SR, Perry JW. Opt Lett. 1997;22:1843. doi: 10.1364/ol.22.001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Köhler RH, Cao J, Zipfel WR, Webb WW, Hanson MR. Science. 1997;276:2039. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kawata S, Sun HB, Tanaka T, Takada K. Nature. 2001;412:697. doi: 10.1038/35089130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bhawalkar JD, Kumar ND, Zhao CF, Prasad PN. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15:201. doi: 10.1089/clm.1997.15.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu XJ, Feng JK, Ren AM, Zhou X. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;373:197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Albota M, et al. Science. 1998;281:1653. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Reinhardt BA, Brott LL, Clarson SJ, Dillard AG, Bhatt JC, Kannan R, Yuan L, He GS, Prasad PN. Chem Mater. 1998;10:1863. [Google Scholar]; c Kim OK, Lee KS, Woo HY, Kim KS, He GS, Wicz JS, Prasad PN. Chem Mater. 2000;12:284. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Wood GL, Miller MJ, Mott AG. Opt Lett. 1995;20:973. doi: 10.1364/ol.20.000973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Drobizhev M, Sigel C, Rebane A. J Lumin. 2000;86:391. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.001633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karotki A, Drobizhev M, Kruk M, Spangler C, Nickel E, Mamardashvili N, Rebane A. J Opt Soc Am B. 2003;20:321. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Drobizhev M, Karotki A, Kruk M, Rebane A. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;355:175. [Google Scholar]; b Drobizhev M, Karotki A, Kruk M, Mamardashvili N, Zh, Rebane A. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;361:504. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Screen TEO, Thome JRG, Denning RG, Bucknall DG, Anderson HL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9712. doi: 10.1021/ja026205k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Ogawa K, Ohashi A, Kobuke Y, Kamadaand K, Ohta K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4050. [Google Scholar]; b Karotki A, Drobizhev M, Dzenis Y, Taylor PN, Anderson HL, Rebane A. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2004;6:7. doi: 10.1021/jp044261x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D, Osuka A, Shigeiwa M. J Phy Chem A. 2005;109:2996. doi: 10.1021/jp050747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullen, K.; Wegner, G. Electronic Materials: The Oligomer Approach; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1998.

- 11.a Horowitz G, Fichou D, Peng XZ, Xu ZG, Garnier F. Solid State Commun. 1989;72:381. [Google Scholar]; b Dimitrakopoulos CD, Malenfant PRL. Adv Mater. 2002;14:99. [Google Scholar]; c Dodabalapur A, Torst L, Katz HE. Science. 1995;268:270. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5208.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Rath H, Anand VG, Sankar J, Venkatraman S, Chandrashekar TK, Joshi BS, Khetrapal CL, Schilde U, Senge MO. Org Lett. 2003;5:3531. doi: 10.1021/ol035408q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rath H, Sankar J, Prabhuraja V, Chandrashekar TK, Joshi BS, Ray R. Chem Commun. 2005:3343. doi: 10.1039/b502327k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrashekar TK, Venkatraman S. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:676. doi: 10.1021/ar020284n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheik-Bahaei MA, Said A, Wei TD, Hagan J, Van Stryland EW. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 1990;26:760. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sengupta P, Balaji J, Banerjee S, Philip R, Ravindra Kumar G, Maiti S. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:9201. [Google Scholar]

- 16.See the Supporting Information for further details.