Abstract

Microcin B17 (MccB17) is a peptide antibiotic produced by Escherichia coli strains carrying the pMccB17 plasmid. MccB17 is synthesized as a precursor containing an amino-terminal leader peptide that is cleaved during maturation. Maturation requires the product of the chromosomal tldE (pmbA) gene. Mature microcin is exported across the cytoplasmic membrane by a dedicated ABC transporter. In sensitive cells, MccB17 targets the essential topoisomerase II DNA gyrase. Independently, tldE as well as tldD mutants were isolated as being resistant to CcdB, another natural poison of gyrase encoded by the ccd poison-antidote system of plasmid F. This led to the idea that TldD and TldE could regulate gyrase function. We present in vivo evidence supporting the hypothesis that TldD and TldE have proteolytic activity. We show that in bacterial mutants devoid of either TldD or TldE activity, the MccB17 precursor accumulates and is not exported. Similarly, in the ccd system, we found that TldD and TldE are involved in CcdA and CcdA41 antidote degradation rather than being involved in the CcdB resistance mechanism. Interestingly, sequence database comparisons revealed that these two proteins have homologues in eubacteria and archaebacteria, suggesting a broader physiological role.

Microcins are ribosomally synthesized peptide antibiotics produced by diverse strains of gram-negative bacteria (4). Peptide antibiotics have several important features, even though their sequences, structures, and modes of action differ (for reviews, see references 26, 27, 31, and 49): (i) their synthesis is often induced by cessation of growth, (ii) they are synthesized as precursors with an amino-terminal leader peptide that differs from the typical signal sequences of many exported proteins, (iii) they undergo unusual posttranslational modifications, (iv) they are exported out of the cells that produce them, often by a dedicated export system, and (v) the genes involved in modification and export usually form an operon with the structural gene.

Microcin B17 (MccB17) is a 3,093-Da peptide produced by Escherichia coli cells harboring an incFII plasmid called pMccB17 (13). It is active against most enterobacteria. MccB17 production and immunity require seven open reading frames (mcbA, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F, and -G) organized in an operon located on the pMccB17 plasmid (19, 45, 46). The mcbA gene encodes premicrocin B17, the 69-amino-acid precursor of MccB17 (13). Premicrocin B17 is modified by the activity of the mcbB, -C, and -D gene products (MccB17 synthetase), yielding pro-MccB17 (32, 55). The 26-amino-acid leader peptide is required for these modifications and serves as a scaffold for binding of the synthetase complex (33, 43). Modifications result in a stably folded pro-MccB17 and confers antibiotic activity to the molecule (54). The last step in MccB17 maturation is the removal of the leader peptide of pro-MccB17, yielding mature MccB17 (55).

The mcbE and mcbF gene products form the export pump for active MccB17 (17). The product of the last gene in the mccB17 operon, mcbG, confers immunity to MccB17 by an unknown mechanism. A chromosomal gene called pmbA (or tldE) has been implicated in the maturation and secretion of MccB17 (42). The PmbA protein might be either the peptidase responsible for maturation or a chaperone promoting the interaction of pro-MccB17 with the specific McbEF pump, where cleavage would take place. Export seems to be distinct from leader peptide removal, as (i) exogenously added MccB17 is pumped out of target bacteria containing the McbEF pump and (ii) an McbA-LacZ fusion is processed in the absence of McbEF (54).

The effects of MccB17 on sensitive E. coli cells include inhibition of replication, induction of the SOS response, induction of double-strand breaks in DNA by trapping of DNA gyrase complexes, and ultimately cell death (24, 53). An MccB17 resistance mutation (resulting in a Trp751 to Arg substitution) has been mapped to position 2251 of the gyrB gene (14, 53). Two GyrA subunits and two GyrB subunits form the gyrase, a bacterial topoisomerase II. This tetramer catalyzes negative supercoiling in an ATP-dependent reaction (18). The GyrA subunits form the catalytic core of the enzyme and ensure the DNA breaking-rejoining reaction. The GyrB subunits are responsible for ATP binding and hydrolysis. Heddle and collaborators have recently shown that in vitro, MccB17 can induce gyrase-dependent DNA cleavage in the presence of ATP (23). They postulate that the MccB17 action mechanism might be similar to that of synthetic quinolones and the bacterial poison CcdB.

The CcdB poison belongs to the ccd poison-antidote system of the F plasmid (ccd stands for control of cell death) (for a recent review, see reference 15). The CcdA protein is the second component of the ccd system and is the specific antidote against CcdB. Plasmid-encoded poison-antidote systems contribute to plasmid stabilization by killing plasmid-free daughter cells (28, 40). Cell killing relies on differential stability of the toxin and antidote; the toxin is stable, whereas the antidote is degraded by a host-encoded ATP-dependent protease (Lon or Clp). Both in vivo and in vitro, CcdA interacts with CcdB (50, 52). This interaction prevents the cytotoxic activity of CcdB (30). A polypeptide called CcdA41, consisting of the 41 carboxy-terminal amino acids of CcdA, retains the ability to interact with CcdB and thus to prevent its cytotoxic activity (5). It has been shown in vivo and in vitro that the ATP-dependent Lon protease is responsible for CcdA degradation (51, 52). Lon also degrades a synthetic CcdA41 polypeptide in vitro, but unlike that of CcdA, degradation of CcdA41 is ATP independent (52).

Several searches for CcdB-resistant mutants yielded mutations in the groESL, tldD, tldE, and gyrA genes (but not in gyrB, as for MccB17 resistance) (6, 36, 37, 39). From extensive genetic and biochemical studies conducted in our laboratory and others, it appears unequivocally that the target of CcdB is the GyrA subunit of gyrase, encoded by the gyrA gene. CcdB traps DNA gyrase complexes on the DNA, stabilizing a complex (called the cleaved complex) in which the double-stranded DNA is broken and covalently linked to GyrA subunits (7). CcdB-gyrase-DNA complexes form DNA lesions leading to polymerase blocking, SOS induction, filamentation, and cell death (12, 28). In addition, CcdB is a gyrase inhibitor; it binds to free GyrA subunits and forms CcdB-GyrA complexes unable to catalyze supercoiling and DNA cleavage (3, 29, 35). The roles of the groELS, tldD, and tldE genes in CcdB resistance remain unclear, but Murayama and colleagues suggested that the corresponding proteins could enhance the CcdB-gyrase interaction (39). The tldE gene is the same gene as pmbA, previously identified by Rodriguez-Sainz and colleagues as required for the maturation and secretion of MccB17 (42).

In this paper we present in vivo data showing that TldD, as was previously described for TldE (PmbA), is involved in MccB17 secretion (42). The pro-MccB17 accumulates in ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE mutants, showing that both proteins are essential to removal of the 26-amino-acid leader peptide of pro-MccB17. This suggests that they might have proteolytic activity. Accordingly, we have obtained evidence showing that TldD and TldE affect CcdA and CcdA41 antidote stability rather than modulating the CcdB-gyrase interaction, as was proposed previously (39).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The E. coli K-12 strains used in this work were C600 (thr-1 thi-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 supE44), B410 (lacIq thi-1 supE44 endA1 recA1 hsdR17), SG22622 (cpsB::lacZ Δara malP::lacIq), SG22623 (SG22622 Δlon-510), SG22622 gyrA462 (SG22622 containing the gyrA CcdB resistance mutation), CSH50 [(Δlac-pro) ara rpsL thi], and CSH50λsfiA::lacZ (CSH50 lysogen for a λ carrying a transcriptional sfiA::lacZ fusion).

The relevant characteristics and references for the plasmids used in this work are described in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in minimal medium 132 (20) supplemented with the appropriate carbon source and the appropriate amino acid. MacConkey lactose plates (1% final concentration) were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions (Difco). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 12.5 μg/ml; tetracycline, 12.5 μg/ml except for the ΔtldE::tet strains, which were grown on 2.5 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector derived from p15A plasmid, tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance | 10 |

| pCID909 | pACYC184 containing the mccB17-producing genes (mcbABCDEFG), chloramphenicol resistance | 42 |

| pULB2232 | pACYC184 containing the ccdAam22-ccdB operon, chloramphenicol resistance | 6 |

| pKK223-3 | Expression vector containing the ptac promoter and derived from ColE1 plasmid, ampicilin resistance | 9 |

| pKK-tldD | pKK223-3 derivative containing the tldD gene under ptac control | This work |

| pKK-tldE | pKK223-3 derivative containing the tldE gene under ptac control | This work |

| pULB2208 | pKK223-3 containing the ccdA41-ccdB genes under ptac control | 5 |

| pULB2212 | pKK223-3 containing the ccdA41am22-ccdB genes under ptac control | 5 |

| pULB2250 | pKK223-3 derivative containing the ccdB gene under ptac control | 7 |

| pULB2705 | pKK223-3 derivative containing the ccdA and ccdB genes under ptac control | 44 |

| pULB3565 | pKK223-3 derivative containing the ccdA gene under ptac control | D. Jaloveckas (unpublished data) |

| pBAD24 | Expression vector containing the pBAD promoter and derived from ColE1 plasmid, ampicilin resistance | 21 |

| pULB3571 | pBAD24 derivative containing the ccdA41 gene under pBAD control | D. Jaloveckas (unpublished data) |

Construction of TldD and TldE expression vectors.

The tldD open reading frame (ORF) was PCR amplified using primers tldD1 (5′-GCGGAATTCATGAGTCTTAACCTGG) and tldD2 (5′-GCGCTGCAGACCGTTCGTGCACGTAG). The EcoRI and PstI restriction sites in the primers are underlined. The resulting 1,516-bp PCR product was digested with EcoRI and PstI and cloned into the pKK223-3 vector to yield pKK-tldD. The pKK-tldE vector was constructed the same way using primers tldE1 (5′-GCGGAATTCATGGCACTTGCAATG) and tldE2 (5′-GCGCTGCAGGTCGCGCCAG). The constructs were verified by DNA sequencing, and protein production was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Construction of the tldD and tldE knockout vectors.

The pKK-ΔtldD::kan knockout vector was constructed by replacement of the whole ORF with a kanamycin resistance gene. A 2,551-bp SmaI-HindIII fragment containing the tldD gene with its promoter was obtained by PCR using primers tldD25a (5′-GCGCCCGGGTTGACTCCATTCGCAGCACC) and tldD25b (5′-GCGAAGCTTGGATTCCAGCCTGTTTTCCC). The fragment was digested with SmaI and HindIII and then ligated into the pKK223-3 vector cut with the same enzymes. The ligation product was used to transform B410 (recA) to prevent homologous recombination. The resulting construct was digested with PstI (located upstream from the promoter of the tldD gene) and HindIII (located downstream from the tldD gene) to remove a 2,095-bp fragment containing the tldD gene.

The final knockout vector was constructed by ligating the PstI-HindIII vector fragment to a fragment having homology with the region downstream from the tldD gene, obtained by PCR with primers tldDB1 (5′-GCGCTGCAGCTTTCTACGTGCACGAACGGTCC) and tldDB2 (5′-GCGAAGCTTCAACCTCAAACGAACAGTCGCG) and the 1,240-bp kanamycin resistance gene of pUC4::kan flanked by PstI sites. The resulting construct, pKK-ΔtldD::kan, was sequenced to confirm the correct insertion of the kanamycin cassette.

Plasmids pKKΔtldE::kan and pKKΔtldE::tet containing the kanamycin and the tetracycline resistance gene, respectively, were constructed in two steps. The first step was to ligate the upstream and downstream fragments flanking the tldE gene into the pKK223-3 vector cut with EcoRI and HindIII. The 1,494-bp upstream fragment was obtained by PCR with tldEA1 (5′-CAACCTTGAATTCGATCACGCCGATATCTTTGACG) and tldEA2 (5′-ACGACGTTCCCGGGGATGACATCGAAGACGAAG) and cut with EcoRI and SmaI. The 1,134-bp downstream fragment was obtained by PCR with tldEB1 (5′-GTGAATGAGGCCCGGGGAGCGTACTCGCAGTACG) and tldEB2 (5′-GGCAGATAGGTTAAGCTTCACTCTGAGCTAAGC) and cut with SmaI and HindIII. The three fragments were ligated to give rise to the pKK-ΔtldE vector.

In a second step, pKK-ΔtldE::kan was obtained by cloning the 1,248-bp kanamycin resistance gene of pUC4::kan flanked by HincII sites into the unique SmaI site on the pKK-ΔtldE plasmid. The resulting construct was sequenced. Plasmid pKK-ΔtldE::tet was constructed by cloning the 1,836-bp tetracycline resistance gene into the SmaI site of pKK-ΔtldE. The tetracycline resistance gene flanked by SmaI sites was obtained by PCR with primers tet1 (5′-TTGAGTCCAACCCGGGAAGACATGCA) and tet2 (5′-TACCCGGGTCCTCAACGACAGG) and the pACYC184 vector as the template.

Construction of the tldD and tldE deletion mutants.

The kan or tet insertion in tldD or tldE was transferred into the chromosome by linear transformation of JC7623 (recBC sbcBC) (25). Plasmid pKK-ΔtldD::kan cut with SphI and NdeI was introduced to create JCΔtldD::kan. Plasmids pKK-ΔtldE::kan and pKK-ΔtldE::tet were cut with ScaI and NdeI and introduced into the recipient strain to create JCΔtldE::kan and JCΔtldE::tet, respectively. Antibiotic-resistant colonies were purified and checked by PCR using primers tldDA1 and tldDB2 for the tldD deletion and tldEA1 and tldEB2 for the tldE deletion. The mutations were transduced into SG22622, SG22623, CSH50, and CSH50λsfiA::lacZ as described by Silhavy et al. (48).

Sample preparation by TCA precipitation, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis with anti-CcdA and anti-CcdB.

Samples (1 ml) were removed from cultures and precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 5% final concentration). After centrifugation, the pellets were washed twice with 500 μl of ice-cold 100% acetone and resuspended in the appropriate volume of SDS gel loading buffer. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by 15% tricine-SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes at 200 V for 30 min. The membranes were incubated overnight at room temperature with polyclonal anti-CcdA or anti-CcdB antibodies. Immunoblots were developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibody, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia).

Radiolabeling of proteins and preparation of total cell extracts and culture supernatants.

Bacteria were grown at 37°C in minimal medium 132 supplemented with glucose (0.4%) and appropriate amino acids and antibiotics until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Samples were labeled with [35S]cysteine or [14C]leucine for 5 min at 37°C. Then 1-ml samples of each culture were TCA precipitated (5% final concentration) and washed with acetone to prepare total cell extracts. For supernatant preparation, 10-ml samples were centrifuged twice for 10 min at 13,000 × g and 4°C. Supernatants were filtered, TCA precipitated (10% final concentration), and washed twice with 500 μl of ice-cold acetone. Pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of SDS loading buffer and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Then 10 μl of each sample was electrophoresed on an 18.5% polyacrylamide SDS-PAGE gel.

RESULTS

Both TldE and TldD are required for maturation and export of MccB17 and are not interchangeable.

Rodriguez-Sainz et al. proposed that a tldE mutant strain (described as a pmbA1 mutant) is deficient in maturation and secretion of MccB17 (42). Using a recA::lacZ fusion, they observed strong induction of the SOS system in the pmbA1 strain carrying a plasmid encoding MccB17. They suggested that this mutant can synthesize a cytoplasmic form of MccB17 (most likely a pro-MccB17 containing the 26-residue amino-terminal leader sequence) but cannot secrete it.

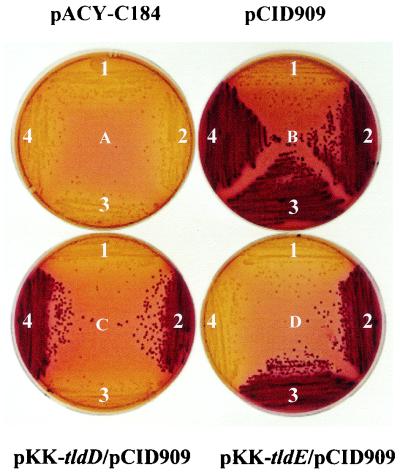

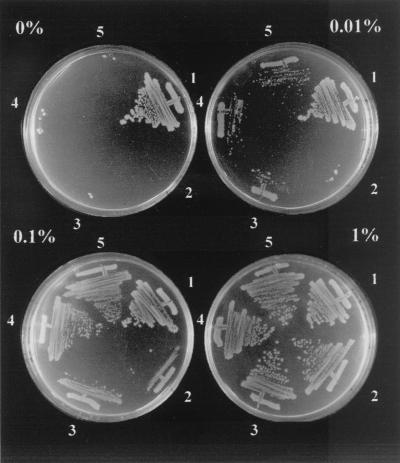

To examine the roles of the tldD and tldE genes in MccB17 production and excretion, we constructed insertion and deletion mutants of both genes and introduced them by P1 transduction into CSH50 lysogenized with a λsfiA::lacZ fusion (see Materials and Methods). SOS induction was tested in the wild-type strain CSH50λsfiA::lacZ and in isogenic tldD, tldE, and tldD tldE deletion mutants containing MccB17-producing plasmid pCID909 or the pACYC184 control vector. This test was done on MacConkey lactose plates. When they harbored pCID909, the ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE mutants all displayed the Lac+ phenotype, indicative of strong SOS induction (Fig. 1B, 2, 3, and 4). No SOS induction was observed in any of these strains when they harbored pACYC184 (Fig. 1A, 1 to 4) or in the wild-type strain carrying pCID909 (Fig. 1B, 1). These results were confirmed by measuring the β-galactosidase activity produced by these strains in liquid culture (data not shown). Strong SOS induction was observed both in single-deletion mutants and in the double mutant. It was maximal when the bacteria entered the stationary phase (OD600 = 1.5), the phase in which synthesis of MccB17 is also maximal (11).

FIG. 1.

SOS induction triggered by an MccB17-producing plasmid (pCID909) in the tld deletion mutants. Induction of the SOS system was monitored using an sfiA::lacZ fusion. Isogenic strains CSH50 λsfiA::lacZ (strain 1) and its ΔtldD ΔtldE (strain 2), ΔtldD (strain 3), and ΔtldE (strain 4) mutants containing the plasmids indicated in the figure were streaked on MacConkey plates containing 1% lactose. The picture was taken after overnight incubation at 37°C. Plate A, the four strains carried the pACYC184 control vector. Plate B, the four strains carried the pCID909 plasmid. Plate C, the four strains carried the pKK-tldD and pCID909 plasmids. Plate D, the four strains carried the pKK-tldE and pCID909 plasmids.

We checked MccB17 secretion in all three pCID909-carrying mutant strains by stabbing isolated colonies of these strains on a lawn of MccB17-sensitive bacteria (C600). As shown in Fig. 2, the wild-type strain produced a halo of growth inhibition around the inoculum, indicative of the presence of active secreted MccB17. Neither the single-deletion mutants nor the double mutant produced any halo of growth inhibition. Together these results show that, like the ΔtldE mutant, both the ΔtldD mutant and the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant can produce a form of MccB17 that is able to induce the SOS system (Fig. 1). It is likely that this form is pro-MccB17, as previously suggested (42). This form is either not secreted or not competent for uptake by MccB17-sensitive bacteria (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Lack of lysis around tld deletion mutants. Lysis tests were carried out by stabbing individual colonies on a lawn of sensitive bacteria (C600). The CSH50λsfiA::lacZ and isogenic tld mutants and the plasmid they contained (pACYC184 or pCID909) are indicated.

Because TldD and TldE have 20% identity at the protein level (39), we tested whether they are interchangeable. Using a pKK223-3 expression vector carrying either the tldD or the tldE gene, we performed a complementation analysis of the Δtld mutations in λsfiA::lacZ lysogens containing the pCID909 MccB17-producing plasmid. We observed that pKK-tldD is unable to reverse the Lac+ phenotype of the ΔtldE or ΔtldD ΔtldE strain (Fig. 1C). Likewise, the pKK-tldE vector was unable to reverse the Lac+ phenotype of the ΔtldD or ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant strain (Fig. 1D). These results show that overproduction of one Tld protein cannot suppress the effect of the absence of the other.

Pro-MccB17 form of MccB17 accumulates in the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant.

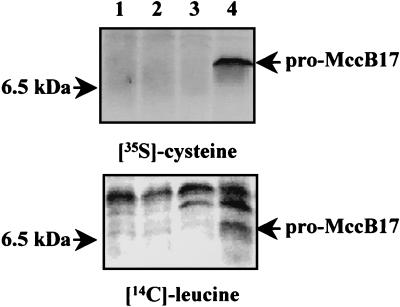

It has been proposed that the form that accumulates in the pmbA1 mutant (tldE mutant) differs from mature MccB17 only by the presence of the 26-amino-acid leader peptide (pro-MccB17) (42), yet accumulation of pro-MccB17 has never been demonstrated in this mutant. Therefore, we examined whether total cell extracts of wild-type and ΔtldD ΔtldE strains contain the pro-MccB17 form of microcin. We took advantage of the fact that the MccB17 leader peptide contains five leucine residues (out of 26) and mature MccB17 contains none (54).

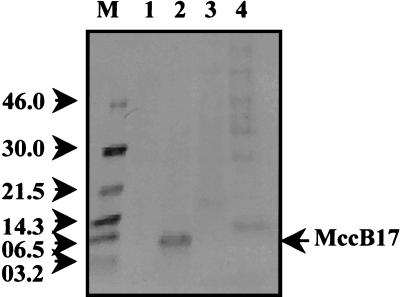

The wild-type and ΔtldD ΔtldE strains containing either the pCID909 MccB17-encoding plasmid or the pACYC184 control vector were labeled with either [35S]cysteine (labeling of MccB17) or [14C]leucine (labeling of the leader peptide). Figure 3 shows that the ΔtldD ΔtldE strain accumulated a low-molecular-mass protein (6.5 kDa) labeled with both amino acids (leucine and cysteine), most likely corresponding to pro-MccB17. This protein was not detected in the pACYC184-containing strains or in the wild type harboring pCID909. The latter fact suggests very rapid maturation and excretion of MccB17 into the extracellular medium by the wild-type strain. Indeed, when we analyzed the culture supernatants, we found a band near 5.0 kDa in the supernatant of the wild type harboring the pCID909 plasmid (Fig. 4, lane 2).

FIG. 3.

Accumulation of pro-MccB17 in tld deletion mutants. Cultures were labeled with [35S]cysteine (upper panel) or [14C]leucine (lower panel), and total cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The position of the 6.5-kDa molecular mass marker is indicated on the left and that of pro-MccB17 is on the right. The strains are derivatives of CSH50λsfiA::lacZ carrying the MccB17-producing plasmid pCID909 or the pACYC184 vector control. Lane 1, wild type/pACYC184; lane 2, wild type/pCID909; lane 3, ΔtldD ΔtldE/pACYC184; lane 4, ΔtldD ΔtldE/pCID909.

FIG. 4.

Mature form of MccB17 is detected in supernatants of wild-type strain cultures but not in those of tld deletion mutant cultures. Cultures were labeled with [35S]cysteine, and supernatant samples were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Lane M, molecular mass markers; lane 1, wild type/pACYC184; lane 2, wild type/pCID909; lane 3, ΔtldD ΔtldE/pACYC184; lane 4, ΔtldD ΔtldE/pCID909. Mature MccB17 is indicated by an arrow.

An aliquot of the wild-type supernatant was active against MccB17-sensitive bacteria (data not shown). This band, most likely corresponding to mature MccB17, was not present in the supernatants of the other strains. In the case of the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant, the extracellular medium displayed several proteins of different molecular masses that were not present in the supernatant from the wild-type strain. These bands most likely correspond to cytoplasmic proteins, suggesting that the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant containing pCID909 might be subject to lysis. One of the bands showed a molecular mass of near 6.5 kDa and could correspond to pro-MccB17 (Fig. 4, lane 4).

Pro-MccB17 is not competent for uptake by bacteria.

As mentioned above (Fig. 2), we observed no halo of growth inhibition when the mutant strains (ΔtldD, ΔtldE, or ΔtldD ΔtldE) harboring the pCID909 plasmid were stabbed on a lawn of MccB17-sensitive cells. To test the ability of sensitive bacteria to take up pro-MccB17, we tested the effect of the supernatants of overnight cultures and total protein extracts of pCID909-harboring wild-type and ΔtldD ΔtldE strains on a lawn of sensitive cells (data not shown). In the case of the wild-type strain, both the supernatant and the protein extract produced a halo of growth inhibition. In the case of the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant, neither the extract nor the culture supernatant produced a halo. Thus, in addition to being nonsecretable, pro-MccB17 is not competent for OmpF-dependent uptake by sensitive bacteria. The presence of the leader peptide thus inhibits both the export and the uptake of MccB17.

Deletion of tldD, tldE, or both does not confer resistance to the CcdB poison.

In their screen to identify genes involved in the CcdB-gyrase interaction, Murayama and colleagues isolated CcdB-tolerant tldD and tldE mutants (39). To further investigate the effect of tldD and tldE mutations on CcdB resistance, we transformed SG22622 (lacIq) and isogenic ΔtldD, ΔtldE, ΔtldD ΔtldE, and CcdB-resistant gyrA462 strains with plasmids containing either the ccdA41 ccdB operon (pULB2208 and pULB2212), the ccdAB operon (pULB2705), or the ccdB gene alone (pULB2250). In these pKK223-3 derivatives, the specified ccd gene(s) is under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-regulated tac promoter.

Table 2 shows the transformation efficiencies recorded in this experiment. In the absence of IPTG, all three deletion mutants yielded transformants harboring pULB2208 (expressing CcdA41 and CcdB) with comparable efficiency. Surprisingly, the wild-type strain did not. In the presence of IPTG (i.e., when CcdA41 and CcdB were overexpressed), pULB2208 was able to transform the wild-type strain. Thus, deletion of the tldD and/or tldE gene enables the mutant strains to carry a plasmid expressing CcdA41 and CcdB (pULB2208) under conditions (absence of IPTG) in which a wild-type strain cannot. This effect of the tldD and tldE gene products was revealed only at a low level of CcdA41 and CcdB protein expression. The only strain to be transformed by pULB2212 or pULB2250 (encoding only CcdB), regardless of whether IPTG was present, was the CcdB-resistant gyrA462 strain. Thus, deletion of tldD and/or tldE does not allow transformation by a plasmid expressing CcdB alone.

TABLE 2.

Effect of tldD and/or tldE deletion on the transformation efficiency of a plasmid expressing the CcdA41 and CcdB proteinsa

| Strain | Transformation efficiency

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pULB2208

|

pULB2212

|

pULB2250 (− IPTG) | pULB2705 (− IPTG) | |||

| − IPTG | + IPTG | − IPTG | + IPTG | |||

| SG22622 | <0.001 | 1.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9 |

| SG22622 ΔtldD | 1 | 1.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9 |

| SG22622 ΔtldE | 0.9 | 0.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.2 |

| SG22622 ΔtldD ΔtldE | 1.4 | 1.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.7 |

| SG22622 gyrA462 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

Isogenic strains were transformed with equal amounts of plasmid DNA expressing CcdA41 and CcdB (pULB2208), CcdB alone (pULB2212 and pULB2250), or CcdA and CcdB (pULB2705). Transformation efficiency was calculated by dividing the number of transformants obtained with the plasmid bearing the ccd genes by the number of transformants obtained with the pKK223-3 control vector. Similar results were obtained at least three times.

To rule out a possible copy number effect, we used the λpSC138 ccdAam22ccdB phage-plasmid hybrid expressing only the CcdB protein and behaving like a one-copy plasmid in sup+ λ lysogens. This hybrid failed to transform the wild-type and the tld deletion strains but gave transformants in the gyrA462 CcdB-resistant mutant (data not shown). Plasmid pULB2705 (expressing CcdA and CcdB) transformed all strains with comparable efficiency. These results show that deletion of tldD and/or tldE does not confer resistance to the CcdB protein per se but seems rather to affect the activity and/or quantity of the CcdA41 antidote.

TldD and TldE proteins are involved in degradation of the CcdA41 and CcdA antidotes.

To confirm that the tldD and tldE gene products interfere with CcdA41 and not with CcdB, we designed a genetic experiment in which CcdA41 expression was varied while that of CcdB was constitutive. For this purpose, the ccdA41 gene was cloned under the control of the tightly regulated pBAD promoter (pULB3571). SG22622 and isogenic gyrA462, ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE strains containing the pULB3571 plasmid were grown in the presence of 1% arabinose and transformed with a compatible pACYC184 derivative expressing the CcdB protein (pULB2232). Transformation mixtures were plated on LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotics and 1% arabinose to fully induce CcdA41 expression. All strains yielded transformants at the same frequency (data not shown), but colony size depended strongly on the expression time before plating, and there was an absolute requirement for arabinose in the medium during that time.

Transformant viability was then assayed on LB plates containing various concentrations of arabinose and the appropriate antibiotics. Figure 5 shows that in the absence of arabinose (nonexpression of CcdA41), only the CcdB-resistant gyrA462 strain could grow (as shown in Table 2). At a low arabinose concentration (0.01%), the ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE strains grew a little, whereas the wild-type strain did not form colonies. In the presence of 0.1% arabinose, production of CcdA41 was sufficient to antagonize the cytotoxic activity of CcdB and thus to allow growth of the ΔtldE strain and the ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant and, to a lesser extent, of the ΔtldD mutant, but still not of the wild-type strain. At 1% arabinose, all of the strains grew well. Thus, when ccdA41 expression is limiting (0.01 or 0.1% arabinose), the ΔtldE and ΔtldD mutants grow better than the wild-type strain. This probably reflects a difference in the amount of CcdA41 in the different strains.

FIG. 5.

Arabinose-dependent CcdA41 expression prevents CcdB-mediated killing. Strain SG22622 and its derivatives, containing pULB3571 (pBAD-ccdA41) and pULB2232 (pACYC184 expressing CcdB), were streaked on LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotics and arabinose at the indicated concentration. The picture was taken after overnight incubation at 37°C. Strain genotypes are as follows: 1, gyrA462; 2, wild type; 3, ΔtldD; 4, ΔtldE; and 5, ΔtldD ΔtldE.

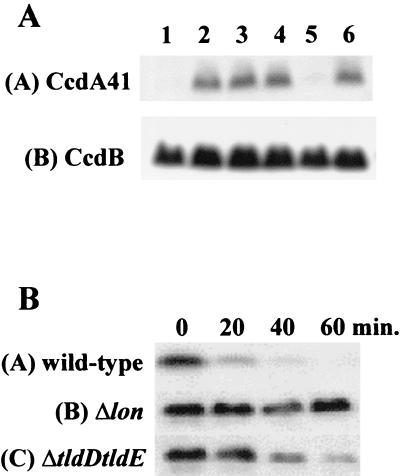

To identify the level at which the TldD and TldE proteins act, we checked by Northern blotting the amount of ccdA41-ccdB mRNA produced by pULB2208 (ptac-ccdA41-ccdB) in the different strains, using a specific probe recognizing the 5′ end of the ccdA41 gene or the ccdB gene (data not shown). The cells were grown in LB medium containing 0.5 mM IPTG to allow growth of the wild-type strain carrying pULB2208. The mRNA pattern was the same for all strains, suggesting that the TldD and TldE proteins do not act at the level of transcription or mRNA stability. We therefore checked the amounts of the CcdA41 and the CcdB proteins under the same conditions by Western blotting with anti-CcdA and anti-CcdB antibodies (Fig. 6A, lane 1). We did not detect any CcdA41 in the wild-type strain, showing that CcdA41 is produced at a very low level or is highly unstable in a wild-type strain. The results were the same in a Δlon strain (Fig. 6A, lane 5) and in ΔclpP and ΔclpQ mutants (data not shown). However, in the ΔtldD, ΔtldE, ΔtldD ΔtldE, and Δlon ΔtldD ΔtldE mutants, we were able to detect CcdA41 (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 to 4 and 6). The amount of CcdA41 in the single mutants was comparable to that in the double deletion mutant, showing that both mutations confer the same phenotype. The amount of CcdB was constant in the different strains (Fig. 6A, B). Similar results were obtained for CcdA41 produced from pULB3571 (pBAD-ccdA41) in the absence of the CcdB protein (data not shown). We thus propose that the TldD and TldE proteins are primarily involved in CcdA41 degradation.

FIG. 6.

Western blot analysis of CcdA41 and CcdA. (A) Analysis of CcdA41 and CcdB produced by the wild-type and by the tld deletion mutants. SG22622 and its derivatives containing pULB2208 (ptac-ccdA41-ccdB) were grown in LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotic and 0.5 mM IPTG. At an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3, 1-ml samples were collected and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CcdA (upper panel) or anti-CcdB (lower panel) antibodies. Strain genotypes are as follows: 1, wild type; 2, ΔtldD; 3, ΔtldE; 4, ΔtldD ΔtldE; 5, Δlon; and 6, Δlon ΔtldD ΔtldE. (B) Analysis of CcdA stability in a tld deletion mutant. SG22622 and its derivatives (Δlon and ΔtldD ΔtldE) containing pULB3565 (ptac-ccdA) were grown in LB containing the appropriate antibiotic to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3. IPTG (0.5 mM) was added to induce CcdA expression for an hour. Spectinomycin was then added (200 μg per ml of culture) to block protein synthesis, and 1-ml samples were collected at the times indicated. Samples were treated and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-CcdA antibodies.

To test the stability of CcdA41 in ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE mutants, we performed a turnover experiment using spectinomycin to block translation and monitored the disappearance of CcdA41 as a function of time. The half-life of CcdA41 is short (<10 min), showing that another protease(s) or peptidase(s) than TldD and TldE is also involved in CcdA41 degradation (data not shown). Because of the effect of the tld genes on CcdA41, we checked their effect on the stability of full-length CcdA. Figure 6B shows that CcdA is partially stabilized in a ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant. This shows that these proteins also affect the stability of CcdA, but to a lesser extent than the Lon protease.

tldD and tldE genes are conserved among archaebacteria and eubacteria.

We used BlastP 2.2.1 (2) to search for homologues to the E. coli TldD and TldE proteins in the current databases. The sequences were found to be very conserved in eubacteria and archaebacteria. Interestingly, TldE homologues were found in the same species as TldD (except for Bradyrhizobium japonicum, but the genome has not been completely sequenced). In general, TldE homologues showed a lesser degree of identity than the TldD proteins. For neither TldD nor TldE did we pick up any significant similarity to proteins or motifs of known function.

DISCUSSION

The ccd system of the F plasmid is composed of the CcdB poison and its cognate antidote, the CcdA protein. CcdA is a 72-amino-acid polypeptide that antagonizes the cytotoxic activity of CcdB by forming a tight complex with it. Despite its small size, CcdA contains two functional domains, the amino-terminal part, involved in DNA binding, and the 41 carboxy-terminal amino acids (CcdA41) that suffice for CcdA oligomerization and binding to CcdB (1, 5, 52). Genetic and biochemical studies have demonstrated that gyrase, an essential topoisomerase II of E. coli, is the target of the CcdB poison (6, 7, 34, 35). In an effort to learn more about the mechanism of action of this poison, Murayama et al. isolated CcdB-resistant mutants (39). Two of the mutations were located in the tldD and tldE genes. They proposed that TldD and TldE might modulate the interaction between the CcdB poison and the GyrA subunit of gyrase. Since the tldE gene had been proposed to be a molecular chaperone involved in the maturation of MccB17 (itself a gyrase poison) (42), these authors further speculated that tldE, and presumably tldD, might have a role more specifically related to gyrase function. Nevertheless, we failed to obtain transformants when we tried to introduce the ccdB gene alone into ΔtldD, ΔtldE, and ΔtldD ΔtldE mutants, whatever the expected expression level, even though we did successfully transform the gyrA462 CcdB-resistant strain. Furthermore, our in vivo data clearly demonstrate that the products of the tldD and tldE genes directly or indirectly regulate the stability of the CcdA and CcdA41 antidotes rather than the CcdB gyrase interactions.

Because the tldE gene was previously implicated in the maturation and secretion of the ribosomally encoded antibiotic MccB17 (42), we also examined the possibility that the tldD gene might play a role in this process. Interestingly, a tldD deletion mutant displays the same phenotype toward MccB17 as does a ΔtldE strain; both mutants produce a form of MccB17 that induces the SOS system but are unable to secrete it. This form has been proposed to be pro-MccB17, still possessing the amino-terminal leader peptide (42). Here we present experimental data supporting this hypothesis. Pro-MccB17 accumulated in a ΔtldD ΔtldE strain. Thus, our in vivo results show that both the tldD and tldE gene products are essential for MccB17 maturation.

There exist various mechanisms for maturation and export of gene-encoded antibiotics. In some cases (e.g., the lantibiotics from gram-positive bacteria), maturation is effected by a specific serine protease, after which the mature antibiotic is exported by an ABC transporter (8, 16). Both the protease and the transporter belong to the antibiotic gene cluster (47). In other cases (e.g., the bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria), processing is carried out by the specific ABC transporter itself (22). In the case of MccB17, no protease-encoding gene is found in the antibiotic operon. The genes essential to maturation, tldD and tldE, are chromosomal and thus located outside the antibiotic gene cluster and even outside the plasmid carrying the MccB17 operon. The presence of tdlD and tdlE homologues in many eubacteria and archaebacteria suggest that the tldD and the tldE genes perform a function(s) besides MccB17 maturation. Unfortunately, very little information is available regarding the function(s) of TldD and TldE homologues.

Streptomyces lincolnensis contains a protein showing well-defined boxes of homology with all the TldD proteins present in the databases. This protein, LmbI, belongs to the lincomycin production gene cluster (41). Lincomycin is an antibiotic from the macrolide lincosamide family. Unlike MccB17, lincomycin is made nonribosomally by linkage of a specific carbohydrate (α-methylthiolincosaminide) to an amino acid derivative (propylproline). The lmbI gene is part of the amino acid metabolism gene subcluster, but its function is still unknown. The other tldD gene, about which a little information is available, is found in B. japonicum (38). It belongs to an operon containing two other genes, one coding for a signal peptidase homologous to SipS and the other for a protein showing homology to SecD (involved in the general secretory pathway) and to peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (involved in protein folding). Thus, these two tldD homologues are associated with antibiotic production or with proteins having posttranslational activities.

We observed that the stability of CcdA41 and, to a lesser extent, that of CcdA is increased in a ΔtldD ΔtldE mutant. Pro-MccB17 failed to be processed in this mutant strain. Thus, these three proteins are direct or indirect substrates of the TldD and TldE proteins. We did not detect any sequence homology between pro-MccB17 and CcdA41 or CcdA. However, their common feature could be a lack of structure. Indeed, in vitro studies have shown that CcdA41 is a very unstructured polypeptide (52), and this is most likely the cause of its high instability in vivo (half-life of <10 min). CcdA is less unstructured than CcdA41 and is also less unstable in vivo (half-life of 40 min) (51). This could be the reason why it is less sensitive to the action of TldD and TldE than CcdA41. Prediction of secondary structure for the leader peptide of MccB17 indicates a lack of structure (31). Therefore, we suggest that TldD and TldE could participate directly or indirectly in biodegradation of unstructured polypeptides.

Our data show that the tldD and tldE genes are part of the same pathway and that they are not interchangeable. Their gene products are involved directly or indirectly in protein processing and degradation. We propose that the TldD and TldE proteins interact and form a proteolytically active complex. Further experiments will be needed to unravel the physiological role of these proteins and the way they function. Interestingly, these proteins appear to be found only in the prokaryotic kingdom.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Geneviève Maenhaut and Michel Faelen for helpful discussion during the course of this work. We thank Nadim Majdalani for helping us with the Northern blots and Natacha Mine for excellent technical assistance. We also thank F. Moreno (Madrid, Spain) and R. Lagos (Santiago, Chile) for providing us with useful bacterial strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) and the Fonds Van Buuren. N.A. was supported by a Télévie Grant. H.A. was supported by the Université Libre de Bruxelles and the Fondation Brachet. M.C. is a Chercheur Qualifié at the FNRS. L.V.M. is Chargé de Recherches at the FNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afif, H., N. Allali, M. Couturier, and L. Van Melderen. 2001. The ratio between CcdA and CcdB modulates the transcriptional repression of the ccd poison-antidote system. Mol. Microbiol. 41:73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahassi, E. M., M. H. O'Dea, N. Allali, J. Messens, M. Gellert, and M. Couturier. 1999. Interactions of CcdB with DNA gyrase. Inactivation of Gyra, poisoning of the gyrase-DNA complex, and the antidote action of CcdA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10936-10944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baquero, F., D. Bouanchaud, M. C. Martinez-Perez, and C. Fernandez. 1978. Microcin plasmids: a group of extrachromosomal elements coding for low-molecular-weight antibiotics in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 135:342-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard, P., and M. Couturier. 1991. The 41 carboxy-terminal residues of the miniF plasmid CcdA protein are sufficient to antagonize the killer activity of the CcdB protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 226:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard, P., and M. Couturier. 1992. Cell killing by the F plasmid CcdB protein involves poisoning of DNA-topoisomerase II complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 226:735-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard, P., K. E. Kezdy, L. Van Melderen, J. Steyaert, L. Wyns, M. L. Pato, P. N. Higgins, and M. Couturier. 1993. The F plasmid CcdB protein induces efficient ATP-dependent DNA cleavage by gyrase. J. Mol. Biol. 234:534-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bierbaum, G., F. Gotz, A. Peschel, T. Kupke, M. van de Kamp, and H. G. Sahl. 1996. The biosynthesis of the lantibiotics epidermin, gallidermin, Pep5 and epilancin K7. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 69:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosius, J., and A. Holy. 1984. Regulation of ribosomal RNA promoters with a synthetic lac operator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:6929-6933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, A. C., and S. N. Cohen. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connell, N., Z. Han, F. Moreno, and R. Kolter. 1987. An E. coli promoter induced by the cessation of growth. Mol. Microbiol. 1:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Critchlow, S. E., M. H. O'Dea, A. J. Howells, M. Couturier, M. Gellert, and A. Maxwell. 1997. The interaction of the F plasmid killer protein, CcdB, with DNA gyrase: induction of DNA cleavage and blocking of transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 273:826-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davagnino, J., M. Herrero, D. Furlong, F. Moreno, and R. Kolter. 1986. The DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17 is a forty-three-amino-acid protein containing sixty percent glycine. Proteins 1:230-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.del Castillo, F. J., I. del Castillo, and F. Moreno. 2001. Construction and characterization of mutations at codon 751 of the Escherichia coli gyrB gene that confer resistance to the antimicrobial peptide microcin B17 and alter the activity of DNA gyrase. J. Bacteriol. 183:2137-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelberg-Kulka, H., and G. Glaser. 1999. Addiction modules and programmed cell death and antideath in bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:43-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Entian, K. D., and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Genetics of subtilin and nisin biosyntheses: biosynthesis of lantibiotics. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 69:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrido, M. C., M. Herrero, R. Kolter, and F. Moreno. 1988. The export of the DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17 provides immunity for the host cell. EMBO J. 7:1853-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellert, M., K. Mizuuchi, M. H. O'Dea, and H. A. Nash. 1976. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:3872-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genilloud, O., F. Moreno, and R. Kolter. 1989. DNA sequence, products, and transcriptional pattern of the genes involved in production of the DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17. J. Bacteriol. 171:1126-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glansdorff, N. 1965. Topography of cotransducible arginine mutations in E. coli K12. Genetics 51:167-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havarstein, L. S., D. B. Diep, and I. F. Nes. 1995. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol. Microbiol. 16:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heddle, J. G., S. J. Blance, D. B. Zamble, F. Hollfelder, D. A. Miller, L. M. Wentzell, C. T. Walsh, and A. Maxwell. 2001. The antibiotic microcin B17 is a DNA gyrase poison: characterisation of the mode of inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 307:1223-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrero, M., and F. Moreno. 1986. Microcin B17 blocks DNA replication and induces the SOS system in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:393-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horii, Z., and A. J. Clark. 1973. Genetic analysis of the recF pathway to genetic recombination in Escherichia coli K12: isolation and characterization of mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 80:327-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack, R. W., and G. Jung. 2000. Lantibiotics and microcins: polypeptides with unusual chemical diversity. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 4:310-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jack, R. W., J. R. Tagg, and B. Ray. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:171-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaffe, A., T. Ogura, and S. Hiraga. 1985. Effects of the ccd function of the F plasmid on bacterial growth. J. Bacteriol. 163:841-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kampranis, S. C., A. J. Howells, and A. Maxwell. 1999. The interaction of DNA gyrase with the bacterial toxin CcdB: evidence for the existence of two gyrase-CcdB complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 293:733-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karoui, H., F. Bex, P. Dreze, and M. Couturier. 1983. Ham22, a mini-F mutation which is lethal to host cell and promotes recA-dependent induction of lambdoid prophage. EMBO J. 2:1863-1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolter, R., and F. Moreno. 1992. Genetics of ribosomally synthesized peptide antibiotics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:141-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, Y. M., J. C. Milne, L. L. Madison, R. Kolter, and C. T. Walsh. 1996. From peptide precursors to oxazole and thiazole-containing peptide antibiotics: microcin B17 synthase. Science 274:1188-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madison, L. L., E. I. Vivas, Y. M. Li, C. T. Walsh, and R. Kolter. 1997. The leader peptide is essential for the posttranslational modification of the DNA gyrase inhibitor microcin B17. Mol. Microbiol. 23:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maki, S., S. Takiguchi, T. Horiuchi, K. Sekimizu, and T. Miki. 1996. Partner switching mechanisms in inactivation and rejuvenation of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase by F plasmid proteins LetD (CcdB) and LetA (CcdA). J. Mol. Biol. 256:473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maki, S., S. Takiguchi, T. Miki, and T. Horiuchi. 1992. Modulation of DNA supercoiling activity of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase by F plasmid proteins. Antagonistic actions of LetA (CcdA) and LetD (CcdB) proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12244-12251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miki, T., T. Orita, M. Furuno, and T. Horiuchi. 1988. Control of cell division by sex factor F in Escherichia coli. III. Participation of the groES (mopB) gene of the host bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 201:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miki, T., J. A. Park, K. Nagao, N. Murayama, and T. Horiuchi. 1992. Control of segregation of chromosomal DNA by sex factor F in Escherichia coli. Mutants of DNA gyrase subunit A suppress letD (ccdB) product growth inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 225:39-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller, P., K. Ahrens, T. Keller, and A. Klaucke. 1995. A Tn phoA insertion within the Bradyrhizobium japonicum sipS gene, homologous to prokaryotic signal peptidases, results in extensive changes in the expression of PBM-specific nodulins of infected soybean (Glycine max) cells. Mol. Microbiol. 18:831-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murayama, N., H. Shimizu, S. Takiguchi, Y. Baba, H. Amino, T. Horiuchi, K. Sekimizu, and T. Miki. 1996. Evidence for involvement of Escherichia coli genes pmbA, csrA and a previously unrecognized gene, tldD, in the control of DNA gyrase by letD (ccdB) of sex factor F. J. Mol. Biol. 256:483-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogura, T., and S. Hiraga. 1983. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:4784-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peschke, U., H. Schmidt, H. Z. Zhang, and W. Piepersberg. 1995. Molecular characterization of the lincomycin-production gene cluster of Streptomyces lincolnensis 78-11. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1137-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Sainz, M. C., C. Hernandez-Chico, and F. Moreno. 1990. Molecular characterization of pmbA, an Escherichia coli chromosomal gene required for the production of the antibiotic peptide MccB17. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1921-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy, R. S., S. Kim, J. D. Baleja, and C. T. Walsh. 1998. Role of the microcin B17 propeptide in substrate recognition: solution structure and mutational analysis of McbA1-26. Chem. Biol. 5:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salmon, M. A., L. Van Melderen, P. Bernard, and M. Couturier. 1994. The antidote and autoregulatory functions of the F plasmid CcdA protein: a genetic and biochemical survey. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244:530-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.San Millan, J. L., C. Hernandez-Chico, P. Pereda, and F. Moreno. 1985. Cloning and mapping of the genetic determinants for microcin B17 production and immunity. J. Bacteriol. 163:275-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.San Millan, J. L., R. Kolter, and F. Moreno. 1985. Plasmid genes required for microcin B17 production. J. Bacteriol. 163:1016-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siezen, R. J., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Comparison of lantibiotic gene clusters and encoded proteins. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 69:171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silhavy, T. J., L. M. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 49.Skvirsky, R. C., L. Gilson, and R. Kolter. 1991. Signal sequence-independent protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria: colicin V and microcin B17. Methods Cell Biol. 34:205-221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tam, J. E., and B. C. Kline. 1989. The F plasmid ccd autorepressor is a complex of CcdA and CcdB proteins. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Melderen, L., P. Bernard, and M. Couturier. 1994. Lon-dependent proteolysis of CcdA is the key control for activation of CcdB in plasmid-free segregant bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 11:1151-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Melderen, L., M. H. Thi, P. Lecchi, S. Gottesman, M. Couturier, and M. R. Maurizi. 1996. ATP-dependent degradation of CcdA by Lon protease. Effects of secondary structure and heterologous subunit interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27730-27738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vizan, J. L., C. Hernandez-Chico, I. del Castillo, and F. Moreno. 1991. The peptide antibiotic microcin B17 induces double-strand cleavage of DNA mediated by E. coli DNA gyrase. EMBO J. 10:467-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yorgey, P., J. Davagnino, and R. Kolter. 1993. The maturation pathway of microcin B17, a peptide inhibitor of DNA gyrase. Mol. Microbiol. 9:897-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yorgey, P., J. Lee, J. Kordel, E. Vivas, P. Warner, D. Jebaratnam, and R. Kolter. 1994. Posttranslational modifications in microcin B17 define an additional class of DNA gyrase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:4519-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]