Abstract

Genital tract trauma following spontaneous vaginal childbirth is common, and evidence-based prevention measures have not been identified, beyond minimizing the use of episiotomy. This study randomized 1211 healthy women in midwifery care at the University of New Mexico teaching hospital to one of three care measures late in the second stage of labor:1) warm compresses to the perineal area, 2) massage with lubricant, or 3) no touching of the perineum until crowning of the infant’s head. The purpose was to assess whether any of these measures was associated with lower levels of obstetric trauma. After each birth, the clinical midwife recorded demographic, clinical care, and outcome data, including the location and extent of any genital tract trauma. The frequency distribution of genital tract trauma was equal in all three groups. Individual women and their clinicians should decide whether to use these techniques based on maternal comfort and other considerations.

Keywords: childbirth, midwifery, perineal management, genital tract trauma, perineal trauma

Introduction

Approximately three million women give birth vaginally each year in the United States1 and most experience trauma to the genital tract from episiotomy, spontaneous obstetric lacerations, or both2. Since 1980, the frequency of use of episiotomy has steadily declined from 64% of vaginal births to under 30%, but in this same interval, repaired obstetric perineal lacerations have risen from 11%, to over 40% in vaginal births. 2,3 The continued decline in usage of episiotomy is supported by evidence from research, which shows that routine episiotomy confers more harm than benefit4. But no evidence is available on how best to reduce spontaneous genital tract lacerations following normal, vaginal childbirth.

Trauma to the genital tract at birth can cause short-term and long-term problems for new mothers. The degree of postnatal morbidity is directly related to the extent and complexity of genital tract trauma5. Short-term problems (immediately following birth) include blood loss, need for suturing, and pain. Protracted pain and varying degrees of functional impairment affect many women as well. At 8 weeks after birth, 22% of new mothers have reported continued perineal pain, and for some women, pain may persist for a year or longer6. Genital tract lacerations following childbirth also weaken the pelvic floor muscles. Thus bowel, urinary, and sexual function after childbirth may be adversely affected 7. Finding ways to prevent even some of this trauma would therefore benefit many women. It would also simplify postpartum care by reducing the need for drugs, suturing, treatments, and future office visits to help women cope with the aftermath of genital tract trauma.

Midwives utilize a variety of hand techniques in the second stage of labor, whether practicing in or out of hospitals, in the belief that these may help lower genital tract trauma rates following vaginal birth8,9. Two techniques, warm compresses and massage with lubricant, have potential therapeutic effects as detailed in textbooks for physical therapists and massage therapists. These include vasodilatation and increased blood supply, tissue stretching or extensibility, muscle relaxation, and altered pain perception10–13. The choice of hand maneuvers is a clinical decision at every birth, and may vary according to patient data, clinician preference, and institutional norms. At present, no firm evidence supports any specific recommendations on perineal management in the time period prior to vaginal birth to reduce spontaneous lacerations.

The main objective of this study was to compare perineal management techniques late in the second stage of labor to determine if any method was more effective in reducing trauma in the genital tract with spontaneous vaginal birth14. The techniques compared were 1) warm compresses, 2) massage with lubricant, or 3) no touching of the perineum until crowning of the infant’s head,. The primary dependent variable was an intact genital tract (defined as no tissue separation at any site) after the birth.

Methods

Time Frame and Study Setting

This study was carried out at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC), from 2001 to 2005. Randomization of women in labor occurred over 38 months (October 2001 to December 2004). During this period, no substantive changes occurred in the clinical environment at UNMHSC, the midwifery group, or the patient population.

The University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque is the only teaching hospital in the state of New Mexico.. Midwifery has been a part of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for nearly 30 years. Twelve experienced nurse-midwives maintain a busy clinical practice and teach a variety of students. The midwives conduct over 10,000 ambulatory care visits and approximately 800 births per year at the University Hospital. They also perform didactic and clinical teaching on a variety of topics including identification and suturing of genital tract trauma at birth for nurse-midwifery students, medical students, and interns in family medicine and obstetrics. The patient population primarily consists of non-Hispanic whites, American Indian, and Hispanic women from Albuquerque and the surrounding areas. Evidence-based care regarding episiotomy in vaginal birth is practiced by all birth attendants at UNMHSC (midwives, obstetricians, and family physicians) and the episiotomy rate is under 1% for all provider groups.

Consent and Eligibility

The study protocol and consent forms were approved by the Human Research Review Committee of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (the local Institutional Review Board), and also by the National Indian Health Service Institutional Review Board. Patients in midwifery care at any of five ambulatory care sites were eligible to consent for the study if they were 18 or older, healthy, and expecting a vaginal birth. Verbal and written consent was obtained in English or Spanish by the clinical midwife. Often the consent process was extended over several prenatal care visits to allow full discussion of study participation, and the usual conduct of normal childbirth. A sticker was placed in the standardized prenatal record to indicate consent, refusal, or ineligibility for the study. At hospital admission in labor, if a woman’s chart indicated consent and prenatal eligibility, she was again screened for normalcy and asked if she still wished to participate. Inclusion criteria at the time of randomization included those women previously consented who did not have medical complications and who had with a singleton vertex presentation at term

Sample size

Sample size was estimated using the method of Fleiss15 for the difference in proportions. We established a clinically significant result as an increase in the rate of a completely intact genital tract (no tissue separation at any site) from approximately 20% at baseline to 30%. In order to detect this change with 80% power at the 5% level of statistical significance, the required sample size was 1200 women. This represents 400 women in each of 3 comparison groups (warm compresses, massage with lubricant, and no touch). After 400 women had been randomized in labor, the principal investigator, database manager, and statistician assessed preliminary study findings to determine if any technique was associated with significantly better or worse trauma outcomes. Since none of the three techniques was associated with improved perineal outcomes at that time, the study continued with the original sample size unaltered.

Randomization

Random allocation to one of three perineal management strategies was performed in a ratio of 1:1:1 within balanced blocks of 12. A computer program was used to generate the random allocation series. For each dozen women, four were allocated to compresses, four to massage, and four to hands off, but the sequence varied randomly. Next, sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes were prepared by the database manager and study administrator, and stored in a metal box at a designated place (with restricted access) in the hospital’s labor unit. The clinical midwife selected the lowest numbered envelope, once vaginal birth appeared likely. The envelope contained a card with the study group allocation (warm compresses, massage with lubricant, no touch) and a data sheet to be completed after the birth. When the envelope was drawn, the midwife signed the study register and noted the date and time.

The envelope was opened when fetal descent began. The perineal management allocation was implemented with active fetal descent or when the fetal head was visible with a uterine contraction. Warm compresses or massage with lubricant were applied as continuously as possible until crowning, unless the mother requested they be stopped or the technique changed. Blinding of the clinical midwives and their patients to group assignment was not possible. If at any time clinical circumstances warranted managing care in a different manner, the midwife did so, and documented her reasons.

Key Study Variables and Data Collection

The perineal management techniques were defined as follows: Warm compresses were clean wash cloths made warm by immersion in tap water and squeezed to release excess water. They were held continuously to the mother’s perineum and external genitalia by the midwife’s gloved hand, during and between pushes, regardless of maternal position. Compresses were changed as needed to maintain warmth and cleanliness. Perineal massage with lubricant was gentle, slow massage with two fingers of the midwife’s gloved hand, moving from side to side, just inside the patient’s vagina. Mild, downward pressure (toward the rectum) was applied with steady, lateral strokes which lasted one second in each direction. This motion precluded rapid strokes or sustained pressure. A sterile, water-soluble lubricant was used to reduce friction with massage. Massage was continued during and between pushes, regardless of maternal position, and the amount of downward pressure dictated by the woman’s response. No touch meant no touching of the woman’s perineum during the second stage, until crowning of the infant’s head. Women in all three groups received verbal encouragement, coaching, information, and praise from their midwife. No particular verbal or social interactions were prescribed or prohibited. Data collection after birth included the allocated technique, what was actually done and for how long, and whether the mother asked the midwife to stop or change technique.

After birth, the midwife performed a thorough inspection of the genital tract and noted the site and severity of any trauma. These items were recorded on the post-delivery data sheet, along with whether suturing was performed at any site. An intact genital tract was defined as absence of tissue separation (no trauma whatsoever) at any site.

Additional data items included maternal age, parity, race/ethnicity, years of completed education, body mass index, weight gain in pregnancy, use of antepartum perineal massage, and history of prior genital tract trauma with vaginal birth. Clinical variables included use of oxytocin and epidural, length of second stage, style of pushing (valsalva versus self-paced without prolonged breath-holding), terminal fetal bradycardia, compound presentation, whether the fetal head delivered with or between contractions, position of the fetal head at delivery (OA, OP, or OT), and complications or unexpected birth events. Outcomes other than trauma included type of delivery, infant birthweight, and Apgar scores. Data were also collected from the postpartum office visit, in particular the presence of anatomic abnormalities, faulty healing of childbirth lacerations, and continued perineal pain.

Data Management

Patient data forms were handled by the clinical midwives or study staff only, all of whom completed training in research ethics and patient confidentiality. Data forms were collected from the hospital several times per week, and entered into a database written especially for this project. The Study Administrator and principal investigator also performed bi-annual chart reviews to retrieve limited data from the 6-week postpartum office visit. The database for the study contained range and frequency checks to reduce the likelihood of data entry errors. After data from 400 births were entered into the database, a 10% random sample of paper records was systematically compared with the computer-entered data, and errors were found to be fewer than one per 1,000 data items.

Clinical Preparation and Intervention Fidelity

Bimonthly meetings of the entire study team took place in the three months prior to randomizing patients, and monthly meetings were held during the first year in order to standardize the consent process, the perineal techniques, assessment of all genital tract trauma, and collecting complete data. Films, pictures and diagrams, role-playing, and demonstration followed by counter-demonstration were used to facilitate discussion and attain consensus. After the first year, quarterly meetings were held to revisit the consent process and study protocol, discuss any problems or concerns of the midwives, and share updates on the study’s progress. Six months after patient randomization began, a second midwife began attending periodic study births, not as a caregiver, but to observe the study intervention and trauma assessment of the clinical midwife. The second observer made a separate recording of what she witnessed, without any discussion with the clinical midwife. These observations occurred at random hospital shifts, if a study birth was in process.

Data Analysis

All randomized patients were included in the analysis, regardless of the route of delivery or whether they actually received the assigned intervention (“intent-to-treat” analysis). Means and proportions were compared for the perineal management groups, including baseline characteristics of study participants, clinical care received, birth outcomes, and trauma experienced. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were generated for the relationship of the hand maneuvers to absence of trauma in women randomized in the first year versus the rest of the study, by parity (first birth versus others), epidural analgesia (yes or no), and infant birthweight (4,000 grams or more, versus under 4,000 grams). A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to assess the association between the length of time that warm compresses or massage with lubricant were applied and the presence or absence of subsequent trauma. Logistic regression was used to assess the predictive relationships of the hand maneuvers to presence of trauma, taking into account potentially related clinical factors. Individual variables that were significantly related to trauma were entered into a regression equation for simultaneous adjustment. Backward elimination was used to delete variables that were insignificant in the presence of the others.

Results

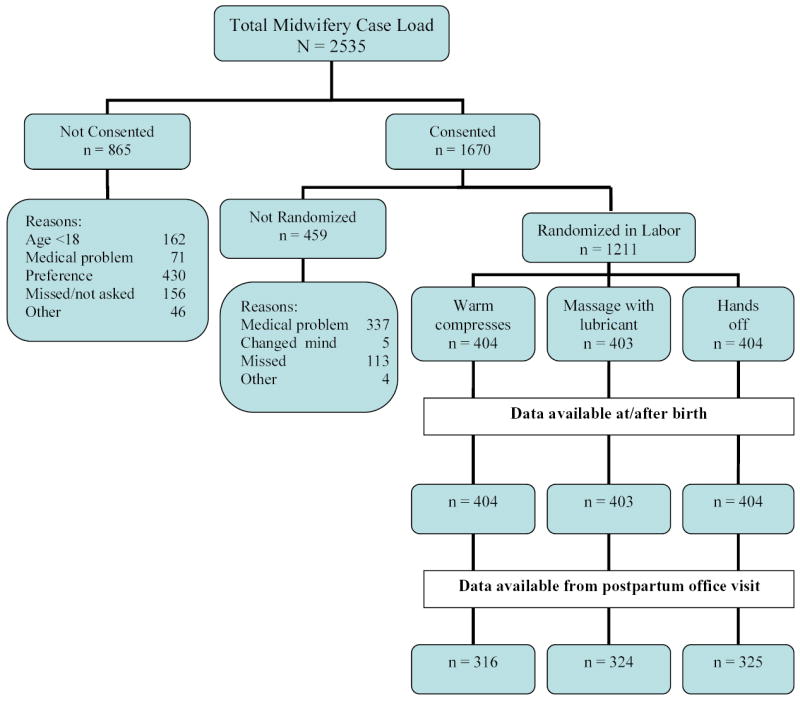

Data were collected from 1211 births over 38 months. The flow of participants through the study is illustrated in Figure 1. Two-thirds of all clients of the UNM midwives consented to participate in the study. Ten percent of women who gave consent were exclusive Spanish speakers. The main reason consent was withheld was maternal preference not to be in a study (17% of all midwifery clients).

Figure 1.

Participant Flow 26 Oct 2001 through 31 Dec 2004

Of women who consented, 72.5% were randomized in the second stage of labor to one of three perineal management strategies. Only five women changed their mind about participating when admitted to the hospital in labor. At admission, 20% of women who had consented were deemed ineligible to participate because of medical problems that had arisen late in pregnancy; the most common problem being gestational hypertension. Because clients under age 18 and those with gestational age less than 37 weeks were excluded from the study there were marginal differences in these variables between non and randomized clients. There were no differences between randomized and non-randomized clients in parity or infant birthweight. . Eighty percent of all randomized women (n=965) had a postpartum office visit with their midwife.

Table 1 shows characteristics of women at trial entry. Randomization produced groups that were evenly matched for all variables. No group differences were statistically significant. The study sample shows considerable ethnic diversity and 40% of all participants were first-time mothers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women at Trial Entry (n=1211) *

| Warm Compresses (n=404) | Massage with Lubricant (n=403) | Hands Off (n=404) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) | |||

| Age, yrs | 24.9 (5.3) | 24.5 (5.2) | 24.5 (5.1) |

| Education, yrs | 12.5 (2.6) | 12.3 (2.6) | 12.3 (2.4) |

| Body mass index † | 25.6 (6.1) | 25.0 (5.3) | 25.5 (5.8) |

| Weight gain in pregnancy, lb | 30.9 (14.2) | 29.9 (13.7) | 30.8 (14.0) |

| N (%) | |||

| Parity 1st birth | 171 (42.3) | 154 (38.2) | 155 (38.4) |

| 2nd birth | 128 (31.7) | 145 (36.0) | 151 (37.4) |

| 3rd birth or higher | 105 (26.0) | 104 (25.8) | 98 (24.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 187 (46.3) | 195 (48.4) | 199 (49.3) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 142 (35.2) | 123 (30.5) | 131 (32.4) |

| American Indian | 58 (14.4) | 65 (16.1) | 49 (12.1) |

| Other | 17 ( 4.1) | 20 ( 5.0) | 25 ( 6.2) |

| Antepartum perineal massage | 4 ( 1.0) | 10 ( 2.5) | 6 ( 1.5) |

| Prior episiotomy or sutured laceration | 152 (37.6) | 162 (40.2) | 155 (38.4) |

Data reported as mean (sd) or number (%)

Body mass index is calculated as weight in kg/height in m2

Compliance with the study protocol is described in Table 2. Midwife self-reported compliance with the random allocation was 94.5% overall, and was similar across intervention groups. One quarter of all study births were observed by a second midwife, and compliance was 95.5% in that subgroup. In 5.8% of all study births, the midwife was asked by the mother to cease the allocated technique. The group of women who received massage with lubricant contained 3/4 of the requests to “stop”.

Table 2.

Compliance with Study Allocation

| Warm Compresses (n=404) | Massage with Lubricant (n=403) | Hands Off (n=404) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported compliance n (%) | 383 (95) | 382 (95) | 380 (94) |

| Patient asked midwife to “stop” allocation n (%) | 9(2.2) | 54(13.4) | 7 (1.7) |

| 2nd Midwife observed study birth | 102 | 88 | 122 |

| Randomized allocation witnessed n (%) | 100 (98) | 83 (94) | 115 (94) |

Table 3 shows data for relevant clinical variables in labor and birth. Spontaneous vaginal birth was achieved by 1187 (98%) of all study participants, and 25 (2%) women had operative deliveries. Nine cesareans occurred late in labor, and 16 women had vaginal operative births (3 by forceps, and 13 vacuum). Only seven infants had a 5-minute Apgar score under 7 (0.6%). Eleven percent of all women had a compound presentation (hand or arm) and nearly 11% had terminal fetal bradycardia. Four out of five women were sitting upright when giving birth. Other positions for birth were: flat with stirrups used by 9.7%; lateral recumbent, 7.4%; and less than 1% each for squatting, hands and knees, or standing.

Table 3.

Distribution of Clinical Variables During Labor and Birth in Three Intervention Groups *

| Warm Compresses (n=404) | Massage with Lubricant (n=403) | Hands Off (n=404) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidural analgesia | 163 (40.4) | 143 (35.5) | 133 (32.9) |

| Oxytocin infusion | 147 (36.4) | 129 (32.0) | 141 (34.9) |

| Terminal fetal bradycardia | 45 (11.1) | 49 (12.2) | 34 (8.4) |

| Sitting upright for birth | 311 (77.0) | 341 (84.6) | 330 (81.7) |

| Non-Valsalva pushing | 314 (77.4) | 312 (77.3) | 328 (81.1) |

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 388 (96.0) | 400 (99.3) | 398 (98.5) |

| Compound presentation | 40 (9.9) | 41 (10.2) | 52 (12.8) |

| Head born between contractions | 136 (33.6) | 122 (30.3) | 139 (34.4) |

| Head born OA (occiput anterior) | 381 (94.3) | 379 (94.0) | 378 (93.6) |

| 5-minute Apgar < 7 | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) |

| Second stage labor, min mean (SD) | 41 (50) | 33 (38) | 36 (44) |

| Infant birthweight, gm mean (SD) | 3351 (437) | 3349 (462) | 3345 (440) |

| Postpartum office visit | 316 (78.2) | 324 (80.4) | 325 (80.4) |

| Postpartum perineal problem | 20 (6.3) | 14 (4.3) | 16 (4.9) |

Reported as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Approximately 23% of all women in the study had a complication or unexpected birth event. These included nuchal cord in 92 births, 42 with meconium, 34 with extreme fetal heart rate abnormalities, 12 precipitate deliveries, 10 with postpartum hemorrhage, 9 (.7%) with shoulder dystocia, 2 with manual removal of placenta, and 1 with a symphysis separation. Of those women who had a postpartum office visit, 5% experienced a perineal problem (continued pain, faulty healing or anatomic abnormality).

Table 4 shows genital tract trauma outcomes. Only 10 episiotomies were cut in the study (0.8%), seven in first-time mothers and three in multiparas. In seven women, the indication for cutting an episiotomy was severe fetal heart rate abnormalities. No episiotomy extended to a third- or fourth-degree laceration. Twenty-three percent (n = 278) of all women experienced no trauma whatsoever, and the genital tract trauma profiles were equal across perineal management groups. Of women who experienced trauma, 242 (20%) had major trauma (defined as a second, third, or fourth degree perineal laceration; a laceration in the mid- or inner vaginal vault; or a cervical laceration) and 691 (57%) had minor trauma (defined as a first degree perineal, outer vaginal, or external genitalia laceration).

Table 4.

Genital Tract Trauma in Three Intervention Groups*

| Warm Compresses (n=404) | Massage with Lubricant (n=403) | Hands Off (n=404) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any trauma | 310 (76.7) | 309 (76.7) | 314 (77.7) |

| No trauma | 94 (23.3) | 94 (23.3) | 90 (22.3) |

| Episiotomy | 1 (0.3) | 7 (1.7) | 2 (0.5) |

| Perineal Trauma: | |||

| 1st degree | 97 (24.4) | 91 (22.6) | 89 (22.0) |

| 2nd degree | 70 (17.3) | 73 (18.1) | 74 (18.3) |

| 3rd degree | 3 (0.7) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| 4th degree | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.0) |

| Location of Other Trauma: | |||

| vaginal | 162 (40.1) | 165 (40.9) | 160 (39.6) |

| labial | 198 (49.0) | 198 (49.1) | 191 (47.3) |

| periurethral | 58 (14.4) | 40 (9.9) | 53 (13.1) |

| clitoral | 16 (4.0) | 13 (3.2) | 20 (4.9) |

| cervical | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Trauma Sutured | 83 (20.5) | 75 (18.6) | 88 (21.8) |

reported as n (%)

Results of the stratified analysis is presented in Table 5, considering four potential confounding factors of parity, epidural usage, infant birthweight, or the first year versus later years of the study that were specified at the outset of the study. The perineal management techniques of warm compresses or massage with lubricant are compared with hands off the perineum separately. In each set of comparisons, both crude and adjusted risk ratios are not significantly different, indicating an absence of confounding from these four variables. Thus, neither warm compresses or massage with lubricant improved the likelihood of an intact genital tract over hands off, when the data were adjusted for parity, epidural usage, infant birthweight, or the first year versus later years of the study.

Table 5.

Predictors of Intact Genital Tract in Stratified Analyses *

| compresses vs hands off Crude RR 1.04 (95% CI .81–1.35) | massage vs hands off Crude RR 1.05 (.81–1/35) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratification variables | stratum-specific risk-ratio | adjusted RR | stratum-specific risk-ratio | adjusted RR |

| Parity | ||||

| First birth | 1.11 (.56–2.16) | 1.09 (.85–1.39) | 1.15 (.89–1.47) | 1.05 (.82–1.33) |

| Other | 1.08 (.83–1.41) | 1.05 (.82–1.33) | ||

| Epidural | ||||

| Yes | 1.26 (.80–1.99) | 1.06 (.82–1.37) | 1.16 (.72–1.89) | 1.05 (.82–1.36) |

| No | .97 (.71–1.32) | 1.01 (.75–1.36) | ||

| Birthweight | ||||

| ≥ 4,000 grams | 1.17 (.32–4.27) | 1.04 (.81–1.34) | 1.64 (.51–5.29) | 1.04 (.81–1.35) |

| Under 4,000 gm | 1.03 (.80–1.33) | 1.02 (.78–1.32) | ||

| Timing | ||||

| 1st year of study | 1.03 (.69–1.54) | 1.04 (.81–1.35) | 1.00 (.67–1.50) | 1.05 (.81–1.35) |

| Later | 1.05 (.76–1.46) | 1.08 (.78–1.50) | ||

reported as RR (95% CI)

For the compress group, the mean time the technique was used was 17.8 minutes (SD=19.5 min) among women with trauma and 13.4 minutes (SD=16.1 min) among women without trauma (P = .06). For the massage group, the mean time was 11.6 minutes (SD=14.0 min) among women with trauma and 5.8 minutes (SD=6.8 min) among women with no trauma (P < .01). Table 6 shows adjusted relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for variables in the final regression model. Absent from the list are the hand maneuvers (compresses and massage), maternal age, body mass index, and length of second stage. Strong predictors of genital tract trauma were nulliparity and high infant birthweight. Modest effects were demonstrated for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white women) and maternal education beyond high school. Two care measures were protective, a sitting position for birth, and delivery of the fetal head between uterine contractions.

Table 6.

– Predictors of Obstetric Trauma: Final Logistic Regression Model *

| Variables | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Nulliparity | 4.59 (3.29–6.64) |

| Birthweight ≥ 4,000 grams | 1.87 (1.17–3.37) |

| Sitting upright for delivery | 0.68 (0.50–0.91) |

| Non-Hispanic whites | 1.34 (1.06–1.73) |

| Education > high school | 1.27 (1.01–1.62) |

| Head born between contraction | 0.82 (0.67–0.99) |

Each variable is adjusted for all others listed here.

Discussion

Results of this study indicate that warm compresses or massage with lubricant provide no apparent advantage or disadvantage in reducing obstetric genital tract trauma, when compared with keeping hands off the perineum late in the second stage of labor. Spontaneous childbirth lacerations are neither more nor less frequent following use of any of the three methods of perineal management tested in this clinical trial.

These results are unlikely to be explained by selection bias. The randomization procedure produced groups that were very similar with regard to demographic and prognostic variables. Midwives followed the ordered sequence of the randomization scheme correctly. Concealment of the allocated perineal strategy from the clinical midwife was not possible. Therefore, the potential for reporting bias in data collected immediately after birth was a possibility. However, with 12 expert midwives participating in the study and no midwife performing over 13% of study births, any clinician bias in data collection would be unlikely to influence group data.

The results are also unlikely to be explained by poor or uneven compliance with the study protocol. Midwife self-reported compliance was very high, and was equal across study groups. This self-reported compliance was documented by a second midwife observer in a random sample of 25% of the study births. To their credit, midwives in the study setting were willing to suspend their individual preferences in perineal management to carry out this investigation. In 84% of births observed by a second midwife, complete agreement between the two midwives occurred for the site and extent of all obstetric lacerations. Three-quarters of disagreements concerned diagnosis of the degree of minor trauma to the external genitalia.

The midwives at UNM have a high degree of expertise in the conduct of normal childbirth, and their rate of an intact genital tract (defined as no tissue separation at any site) in the study was 23%. This is higher than the rate of 16% (using the same definition of “intact”) found in the HOOP trial from the UK16. Studies of perineal outcomes have commonly defined an intact genital tract as “no trauma, or minor and unsutured trauma”. If this broader definition were used in the current study, the midwives’ rate of “intact” would be 73%, a startlingly high rate, given that 40% of all study participants were first-time mothers. Episiotomies are rarely cut by any care providers at the UNM teaching hospital, and the obstetric culture favors patience and vaginal delivery technique that is calm and controlled, with emphasis on slow expulsion of the infant.

Women who experienced genital tract trauma received warm compresses or massage with lubricant for greater time in the second stage of labor, but a cause and effect relationship cannot be assumed from this finding. Other clinical factors associated with a longer second stage could increase the risk of trauma while permitting longer receipt of these perineal care measures.

Multivariate analysis identified six variables that predicted genital tract trauma in this study. Two variables, nulliparity and high infant birthweight, have been repeatedly observed in prior research17. The effects of race/ethnicity and greater maternal education were small but significant. These four factors cannot be altered by clinicians, but may indicate a need for special efforts to minimize genital tract trauma in vaginal birth.

Two care measures were associated with a lower risk of trauma. Giving birth sitting upright and delivery of the infant’s head between uterine contractions are measures familiar to practicing midwives and indicate several things. A sitting position allows the mother greater comfort and autonomy at delivery. It allows face-to-face proximity and direct visual contact between the mother and midwife. Delivery of the head between contractions requires communication, synchrony, and shared responsibility for a slow and gentle expulsion of the infant.

Several factors might limit generalizability of the findings reported here. First, the study setting may be unusual in that episiotomy and vaginal operative procedures are rarely performed by any care providers. This allowed spontaneous lacerations to be a relatively pure focus of the study. In settings where use of episiotomy and vaginal operative procedures are more common, it is difficult to isolate spontaneous trauma from clinician-induced trauma. Second, the 12 midwives who performed this study already have a high degree of expertise at minimizing trauma in vaginal birth. The research team hypothesized at the start of the study that if the hand techniques could lower trauma rates with these clinicians, they would likely have greater health potential elsewhere. Third, the possibility exists that the hand techniques used in this setting might improve patient outcomes in other places where clinicians have higher baseline rates of childbirth lacerations. Warm compresses and massage with lubricant require the constant bedside presence of the birth attendant, which women appreciate. Greater support and intensity of interaction may affect how women respond to what clinicians do. Strengths of the study include the random assignment of the perineal care measures, the large sample of healthy gravidas, the high degree of midwife compliance with the study protocol, and the accuracy of data collection.

Data from this study demonstrated that with rare use of episiotomy and vaginal operative delivery, low rates of serious obstetric trauma were achieved. Most trauma was minor, and affected the external genitalia, the outer vagina, or perineum (first-degree). Neither the use of warm compresses or perineal massage with lubricant late in the second stage of labor increased or decreased the overall rates of genital tract trauma. These results support the choice of perineal management strategy by individual women and their birth attendants, based on maternal comfort and other clinical factors, but not for presumed trauma reduction. However, clinicians are advised to review their usual practices regarding maternal positioning at birth and infant delivery technique to help lower the incidence of obstetric genital tract trauma.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 1 R01 NR05252-01A1 from the National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health. All the UNM midwives share responsibility for the success of this investigation: Ginie Capan, Ellen Craig, Kelly Gallagher, Betsy Greulich, Martha Kayne, Robyn Lawton, Regina Manocchio, Laura Migliaccio, Deborah Radcliffe, Martha Rode, Dympna Ryan, Kay Sedler, and Beth Tarrant.

Footnotes

precis: Selected midwifery strategies for management of the perineum in childbirth (warm compresses, massage with lubricant, or hands off until crowning) were not associated with more or fewer spontaneous lacerations.

bio sketches: Leah Albers, CNM, DrPH, FACNM, FAAN, has been a midwifery teacher and researcher at the University of New Mexico College of Nursing since 1991. She was the PI for this study.

Kay Sedler, CNM, MN, FACNM, has been Chief of the Nurse-Midwifery Division and a faculty member in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center since 1983. She was a co-investigator for the study and managed the clinical operations.

Edward J. Bedrick, Ph.D., is Professor of Statistics at the University of New Mexico. He was the study’s statistician.

Dusty Teaf, MA, is a computer hardware and software expert at the University of New Mexico. She generated the randomized allocation sequence, created the data-entry platform for the study, and served as the database manager.

Patricia Peralta was administrator for the study and coordinated all data collection, entry, and verification. She assisted Dr. Albers with endless details.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Sutton PD. Births: Preliminary data for 2003. National vital statistics reports; vol 53, no 9. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004. [PubMed]

- 2.DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. 2002 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 342. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004. [PubMed]

- 3.Weeks JD, Kozak LJ. Trends in the use of episiotomy in the United States: 1980–1998. Birth. 2001;28:152–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartman K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, Gartlehner G, Thorp J, Lohr KN. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albers L, Garcia J, Renfrew M, McCandlish R, Elbourne D. Distribution of genital tract trauma in childbirth and related postnatal pain. Birth. 1999;26:11–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glazener CMA, Abdalla M, Stroud P, Naji S, Templeton A, Russell IT. Postnatal maternal morbidity: Extent, causes, prevention and treatment. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:282–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glazener CMA. Sexual function after childbirth: Women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albers LL, Anderson D, Cragin L, Daniels SM, Hunter C, Sedler KD, Teaf D. Factors related to perineal trauma in childbirth. J Nurse-Midwifery. 1996;41:269–276. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(96)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy PA, Feinland JB. Perineal outcomes in a home birth setting. Birth. 1998;25:226–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes KW. Manual for physical agents, 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Health, 2000, p. 3–19.

- 11.Behrens BJ, Michlovitz SL. Physical agents: Theory and practice for the physical therapy assistant. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1996, p. 51–56.

- 12.Michlovitz SL (ed). Thermal agents in rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1990, p. 88–108.

- 13.Fritz S. Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage. St. Louis: Mosby Lifeline, 1995, p. 87, 201–202.

- 14.Albers LL. Reducing genital tract trauma at birth: Launching a clinical trial in midwifery. J Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2003;48:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981, p. 266.

- 16.McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, Berridge G, Winter C, Sames L, Garcia J, Renfrew M, Elbourne D. A randomized controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1262–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renfrew MJ, Hannah W, Albers L, Floyd E. Practices that minimize trauma to the genital tract in childbirth: A systematic review of the literature. Birth. 1998;25:143–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1998.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]