Abstract

Rts1, a large conjugative plasmid originally isolated from Proteus vulgaris, is a prototype for the IncT plasmids and exhibits pleiotropic thermosensitive phenotypes. Here we report the complete nucleotide sequence of Rts1. The genome is 217,182 bp in length and contains 300 potential open reading frames (ORFs). Among these, the products of 141 ORFs, including 9 previously identified genes, displayed significant sequence similarity to known proteins. The set of genes responsible for the conjugation function of Rts1 has been identified. A broad array of genes related to diverse processes of DNA metabolism were also identified. Of particular interest was the presence of tus-like genes that could be involved in replication termination. Inspection of the overall genome organization revealed that the Rts1 genome is composed of four large modules, providing an example of modular evolution of plasmid genomes.

Rts1 is a low-copy-number kanamycin resistance plasmid originally isolated from a clinical strain of Proteus vulgaris (56). Its molecular mass was originally estimated to be about 140 MDa (29). This large plasmid is the prototype for the T incompatibility group (9) and expresses pleiotropic thermosensitive phenotypes in autonomous replication (13, 58), conjugative transfer (56), host cell growth (12, 57), and restriction of T-even phages (28, 32, 66).

As in many large plasmids of gram-negative bacteria, Rts1 requires two elements for its autonomous replication, a replication initiation protein encoded by the plasmid (repA) and a short segment containing the replication origin, ori (30, 34, 59). Because the replication of this mini-Rts1 plasmid is stable at 37°C but is inhibited at 42°C in Escherichia coli (30), as observed for Rts1 (56, 58), the replication machinery of Rts1 itself is thermosensitive. A locus termed tdi (temperature-dependent instability) has also been identified as another locus responsible for the temperature sensitivity (48, 55), but its real physiological role in the replication (or maintenance) of Rts1 is unknown.

As for the temperature-sensitive effect on host cell growth, Terawaki et al. (57) first reported that Rts1 inhibits its host cell growth at 42°C but not at 37°C. Since then, two loci responsible for this phenotype have been identified, tsg (43, 47) and hig (60-62). Since the tsg locus contains no open reading frame (ORF), the AT-rich DNA segment itself is thought to be responsible for the thermosensitivity of host cell growth. On the other hand, the hig locus encodes a system belonging to the proteic killer family, where the HigB and HigA proteins function as a toxin and an antitoxin, respectively. The temperature-sensitive host cell growth conferred by the hig system is mediated by selectively killing the host that has lost all copies of Rts1 at a nonpermissive temperature (postsegregation killing).

Conjugation of Rts1 is also thermosensitive, but the temperature range for conjugation differs from that for replication, efficient at 25°C but not at 37°C (56). Thus, the thermosensitivity of conjugation is a phenomenon unrelated to that of replication. The molecular mechanism underlying the thermosensitive conjugation is unknown except that the lengths of Rts1 sex pili were reported to be shorter at 37°C than at 30°C (8). No Rts1 gene for conjugation has been identified.

Another temperature-sensitive phenotype shown by Rts1 is the restriction of T-even phages: Rts1 inhibits the multiplication of T-even phages at 30°C but not at 43°C (66). A locus encoding a restriction enzyme, PvuRts1I, is responsible for this phenomenon (28, 32).

Except for above-mentioned thermosensitive phenotypes, only a few Rts1-related phenomena have been documented so far, and only nine genes have actually been cloned and analyzed. They indeed represent a very small portion of the large gene repertoire encoded on the Rts1 genome. In this study, we determined the entire nucleotide sequence of Rts1, comprising 217,182 nucleotides, and identified all the potential genes encoded by the plasmid. They include the set of genes for the conjugation function and a large number of genes involved in various processes of DNA metabolism. Furthermore, by inspecting the overall genome organization, we identified four modules constituting the Rts1 genome. Among them, two were generated by a large segment duplication and subsequently by structural and sequence diversification. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of the evolution and gene repertoire expansion of large plasmids in general.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Plasmid Rts1, which was originally isolated from P. vulgaris strain UR-75, was conjugatively transferred to and maintained in E. coli ER1648 [F− fhuA2 Δ(lacZ)r1 supE44 trp31 mcrA1272::Tn10(Tetr) his1 rpsL104(Strr) xyl-7 mtl-2 metB1Δ(mcrBC-hsdSMR-mrr)102::Tn10(Tetr)] (32). Plasmid pUC18 (65) and E. coli strains DH5α MCR and DH5α (both from Gibco-BRL) were used to construct random shotgun libraries of the Rts1 genome. E. coli HB101 (leuB6 supE44 thi-1 hsdS20 recA13 ara-14 proAB lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 ntl-1) (7) was used as a recipient strain in the mobilization assay. All strains were cultivated with Luria-Bertani (LB) or 2xYT medium supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 to 200 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 30 μg ml−1; and streptomycin, 500 μg ml−1).

DNA manipulation and sequencing determination.

Routine DNA manipulations were carried out by the standard methods (53). To purify the intact Rts1 plasmid, E. coli strain ER1648 containing Rts1 was cultivated overnight in 2xYT medium containing kanamycin, and the plasmid DNA was extracted with a plasmid kit (Qiagen). The DNA was further purified by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. The whole genome sequence was determined by the random shotgun method as described previously (45, 46). Collected sequences were assembled by the Sequencher sequencing software (version 3.0, gene codes). After the initial assembling of 4,750 sequences obtained by the forward primer (≈500 bases in average), a short region remained to be determined. To fill the sequence gap, 15 clones that covered the gap were selected and sequenced by the reverse primer and custom primers. In addition, 178 clones, the opposite ends of whose inserts were expected to cover the regions with any sequence ambiguity, were selected and sequenced by the reverse primer. The final redundancy of sequencing was about 11-fold, and both strands were read at least once throughout the entire genome.

ORF prediction and computer analysis.

ORFs were predicted with the software GeneMark (6) trained with the matrix generated from a set of genes from various phages and plasmids. In principle, ORFs larger than 150 bp preceded by recognizable ribosome-binding sequences were searched. By this search, 223 ORFs were identified. In the regions where no ORF was identified by GeneMark, ORFs larger than 150 bp with typical ribosome-binding sequences were searched for manually. DNA and protein sequences were compared to the public sequence databases with the Blast program (4) through DDBJ. Multiple alignments of protein sequences were made with ClustalW through DDBJ.

Construction of the physical map.

To construct the physical map of Rts1, the purified plasmid DNA was digested with XbaI, SpeI, SalI, or various combinations of these enzymes. Digested DNAs were analyzed by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis with 0.35 to 0.8% agarose gels prepared by AgaroseH (NipponGene). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was also employed to precisely determine the sizes of large DNA fragments. PFGE was performed with the CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad) on 1% agarose gels (pulsed-field certified agarose, Bio-Rad) in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) and regularly run at 6 V/cm at 14°C with a linear increase in pulse intervals. To resolve fragments of 20 to 120 kb in size, pulse times were ramped from 2.98 to 10.29 s for 26.56 h.

Identification of the oriT locus.

To identify the oriT locus of Rts1, we screened the random shotgun library of Rts1 by the mobilization assay. To construct a pUC18-based library, the purified plasmid DNA was fragmented by sonication, and fragments of 0.5 to 5.0 kb in length were cloned into the SmaI site of pUC18. Resulting plasmids were introduced into E. coli DH5α containing the intact Rts1 that served as a helper plasmid. After precultivation at 28°C, each transformant was incubated with HB101 overnight at 28°C in 96-well microtiter plates. Each coculture was then transferred to fresh medium containing streptomycin and incubated overnight to reduce the background in the screening of transconjugants. Selection of transconjugants was done on LB agar plates containing streptomycin and ampicillin. Sizes of pUC18 derivatives in each transconjugant were analyzed and compared with those in the donor clones to confirm the absence of rearrangement during the mobilization. Frequency of kanamycin-sensitive transconjugants was also examined for each clone to determine whether each clone was transferred by mobilization or cointegration into the helper Rts1 plasmid. Finally, both ends of the inserts were sequenced to map their positions on the Rts1 genome. To further localize the oriT locus, various lengths of DNA fragments covering the oriT-containing region identified by the random screening were generated by PCR, cloned into pUC18, and subjected to the mobilization assay. Nucleotide sequences of all the clones generated by PCR were confirmed by sequencing.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The annotated sequence of Rts1 has been deposited in DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL under accession number AP004237.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General overview.

The Rts1 genome is 217,182 bp in length. The nucleotide position 1 was defined as the guanine that corresponds to position 1441 of the former mini-Rts1 coordinate (34). The physical map deduced from the sequence was the same as that determined experimentally except for an XbaI site at position 127284, but the site contained a GATC sequence which is methylated by Dam methylase (data not shown). The calculated G+C content is 45.7%, close to the value determined by chemical analysis (45%) (19). This value is, however, significantly higher than that of the chromosome of P. vulgaris, from which Rts1 was isolated (39.3% ± 1.2%) (15). This suggests that the original host of Rts1 is not P. vulgaris. There was no substantial region showing atypical base composition (data not shown).

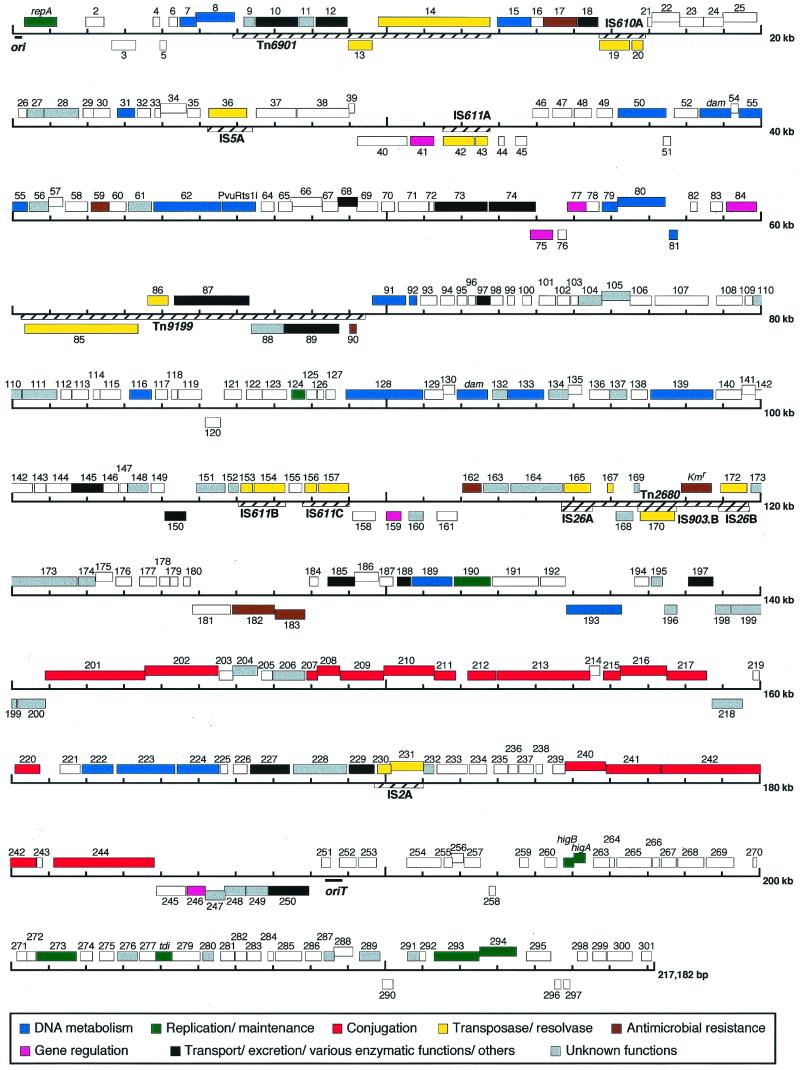

Rts1 encodes 300 ORFs (001 to 165 and 167 to 301, Fig. 1). They indeed include the nine Rts1 genes that were identified previously. Among the 300 ORFs, 253 are oriented in the same direction, left to right in Fig. 1. This remarkable bias may indicate that Rts1 genome replication proceeds mostly in this orientation. In the homology search, the products of 141 ORFs showed significant sequence similarity to known proteins, and among these, 99 were homologous to proteins whose functions are known or predicted. No ORFs directly related to bacterial pathogenesis were identified.

FIG. 1.

Genome organization of Rts1. Boxes indicate ORFs identified on Rts1, and numbers above and below the boxes are ORF numbers. ORFs shown above and below the line are transcribed left to right and right to left, respectively. Predicted functions of ORFs were categorized into eight groups, and ORFs in the same group are indicated by the same color. Locations of ori, oriT, IS elements, and transposons are also indicated.

In the following sections, we will describe the features of Rts1 that have been revealed by analyzing the genome sequence.

Transposon and IS elements.

Rts1 contains six kinds of insertion sequence (IS) elements (nine copies in total) and three transposons (Table 1, Fig. 1). All together, they comprise 28,644 bp, 13% of the plasmid genome. IS610 and IS611 are the ones newly identified in this study, and both belong to the IS3 family. IS611B and IS611C are located very closely (444 bp apart), but they do not appear to form a composite transposon because no target sequence duplication was detected in the regions flanking the two IS elements.

TABLE 1.

Transposon and IS elements on the Rts1 genome

| Element | TSDa (bp) | TIRb (bp) | Location (length in bp) | % Homology (accession no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tn6901 | 5∗ | 52 | 5877-12777 (6,901) | Newly identified |

| IS610A | 3∗ | 38 | 15663-16892 (1,230) | Newly identified |

| IS5A | 4 | 16 | 25205-26399 (1,195) | 100 (J01734) |

| IS611A | 3 | 38 | 31503-32764 (1,262) | Newly identified |

| Tn9199 | — | 78 | 60227-69425 (9,199) | Newly identified |

| IS611B | 3 | 38 | 106039-107300 (1,262) | Newly identified |

| IS611C | 3 | 38 | 107745-109006 (1,262) | Newly identified |

| Tn2680 | 8 | 820 | 114687-119688 (5,002) | Newly identified |

| IS26A | — | 14 | 114687-115506 (820) | 100 (X00011) |

| IS903.B | 9 | 18 | 116718-117774 (1,057) | 99.9 (X02527) |

| IS26B | — | 14 | 118869-119688 (820) | 100 (X00011) |

| IS2A | 5 | 42 | 169698-171028 (1,331) | 100 (V00279) |

Elements, in which one base of the target site duplication (TSD) sequences between the right and left ends are different are indicated by asterisks. Dashes indicate that no such sequences were found.

TIR, terminal inverted repeat.

Tn2680 is a previously identified composite transposon that carries a kanamycin resistance gene [apH(3)′] and is composed of two copies of IS26 and one copy of IS903.B (27, 44), but the complete sequence has been determined in this study. Tn2680 contains additional three ORFs (ORF167, ORF168, and ORF169). Although the functions of ORF168 and ORF169 are unknown, ORF167 is highly homologous to the C-terminal part of a putative transposase (R0148) of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi plasmid R27 (54). The deduced amino acid sequence in the upstream region of ORF167 is also similar to the N-terminal part of R0148 but contains several frameshift mutations.

Tn9199 and Tn6901 are newly identified class II transposons. Besides the genes for transposases and resolvases, each of these transposons carries four ORFs. ORF088 and ORF089 of Tn9199 are similar to a putative ATPase and a putative sulfate permease encoded by Tn2501 on Yersinia enterocolitica plasmid pGC1, respectively (25, 68). The N-terminally truncated arsC gene (ORF090) is present in the upstream region of the two ORFs. ORF087 is similar to BetT, a transporter of choline, which is a precursor of glycine betaine, serving as an osmoprotectant (38). ORF009, ORF010, and ORF012 on Tn6901 are highly homologous to YaiN (90% amino acid sequence identity over the entire length), alcohol dehydrogenase AdhC (94%), and YaiM (78%), respectively, of E. coli K-12. The gene organization is also similar to the yaiN-adhC-yaiM locus on the K-12 chromosome, though an ORF of unknown function is inserted between ORF010 and ORF012 in Rts1.

Conjugation system.

Genes for the conjugation functions are clustered in two regions separated by a 16-kb segment. Most of the gene products show the highest similarities to those of the conjugation systems of plasmid F or plasmid R27, the prototype IncFI and IncHI1 plasmids, respectively (16, 54).

Genes required for the conjugal transfer of plasmid F have been most intensively analyzed, and they are categorized into five groups according to their functions: pilus biosynthesis, aggregate stabilization, conjugal DNA metabolism, surface exclusion, and regulation of gene expression. The genes for sex pilus formation are further divided into two subgroups, those for pilin synthesis and for pilus assembly (reference 16 and references therein). Homologues of all the F genes for pilus assembly except trbI were identified in Rts1. ORF216 shows homology to two pilus assembly proteins of F plasmid, the N-terminal half to TrbC and the C-terminal half to TraW. Although little is known about the exact functions of these F proteins, both are known to be located in the periplasmic space (16). Fusion of the two genes probably indicates that they participate in the same or closely related operational steps in pilus assembly. The same type of gene fusion is observed in plasmid R27, and most of the pilus assembly genes of Rts1 are also similar to the R27 genes (54).

Making a sharp contrast to the pilus assembly genes, no homologues of the F genes for pilin synthesis, traA, traQ, and traX, were identified in Rts1. Instead, Rts1 contains a gene (ORF215) homologous to traF of RP4, which encodes a propilin-specific peptidase (14, 20). R27 also contains a traF homologue, TrhF (54). It should be also noted that ORF185 encodes a type I leader peptidase, which could participate in the first processing step of pilin maturation, removal of the signal peptide.

The aggregate stabilization system of Rts1 is also similar to that of plasmid F, since ORF242 and ORF244 showed similarity to TraG and TraN of plasmid F, respectively. However, no genes homologous to the F genes related to DNA metabolism, surface exclusion, and regulation of gene expression were identified. Instead, ORF201 and ORF202 exhibit significant similarities to a putative nickase (TraI) and an anchoring/coupling protein (TraG) of plasmid R27, respectively (54). These proteins are required for DNA transfer in R27, and thus the DNA transfer system of Rts1 is similar to that of R27.

Among the F genes that are not essential for conjugation but are located in the transfer region, only trbB exhibits a weak and local homology to an Rts1 gene, ORF212. ORF212 is a homologue of DsbC, which catalyzes disulfide bond formation in the periplasmic space (50). A predicted active-site motif, Phe-(X)4-Cys-Pro-Tyr-Cys (42), is conserved in ORF212, and the homology between ORF212 and TrbB of F is limited to a segment containing the motif. DsbC homologues are also present in the transfer regions of R27 (54) and pNL1 (52), suggesting that they play some role as redox proteins in the conjugation process.

ORF197 encodes a protein similar to Nuc, the EDTA resistance endonuclease of pKM101 (49). Nuc homologues are encoded in close proximity to transfer regions in many plasmids belonging to several incompatibility groups (36, 49), though their roles in conjugation are unknown. ORF197 is also located just upstream of the tra gene clusters in Rts1. An extracellular nuclease activity was previously detected in E. coli harboring Rts1 (41), but the relationship between the nuclease activity and ORF197 remains to be elucidated.

Identification of the oriT region.

In the conjugation process, transfer of DNA initiates at a specific site, termed oriT. oriT is usually located at or close to the end of the tra gene cluster, and the tra genes are organized so that they are transmitted late in the conjugation process. Since our first attempt to identify the oriT site of Rts1 by sequence similarity to known oriT sequences of other conjugative plasmids (39) was unsuccessful, we tried to identify the oriT region of Rts1 by screening the genomic DNA library by the mobilization assay as described in Materials and Methods. The principle of this approach is that when the oriT region is cloned into a nonmobilizable plasmid, pUC18, the recombinant plasmid can be mobilized by cohabitation of the parent plasmid (64).

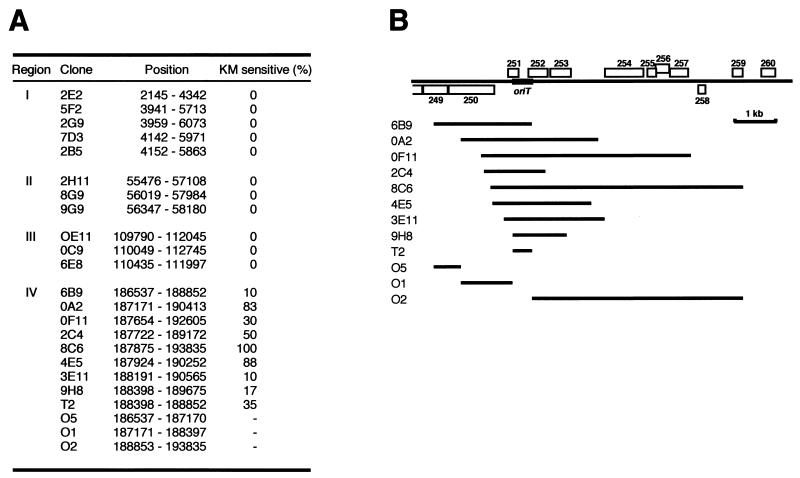

By this screening, we obtained 20 ampicillin-resistant clones. Except for one clone that contained the entire IS611(B), 19 clones were mapped to one of four regions (Fig. 2): positions 2145 to 6073 (region I), 56019 to 57984 (region II), 110435 to 111997 (region III), and 186537 to 193835 (region IV). In the cases of clones derived from regions I, II, and III, kanamycin resistance, a marker of the helper Rts1 plasmid, was always cotransferred with ampicillin resistance (Fig. 2A), implying that they were probably transferred to the recipient cells by cointegration into the helper Rts1 plasmid. In contrast, transfer of the clones derived from region IV was accomplished independently with the helper plasmid, indicating that region IV contains the true oriT site of Rts1. The region was in fact located in close proximity to the transfer region.

FIG. 2.

Identification of the oriT locus of Rts1. (A) Summary of oriT screening. Clones obtained in the oriT screening of the random shotgun library of the Rts1 genome are listed, and their map positions and kanamycin sensitivities are presented. All the clones were derived from one of the four regions, I to IV, but the clones derived from regions I, II, and III were always cotransferred with kanamycin resistance, a marker of helper plasmid Rts1. (B) Map positions of the clones derived from region IV and those prepared by PCR. The T2 segment represents the minimum consensus of the eight random clones obtained in the oriT screening. The T2 segment was able to mobilized by Rts1, but the segments outside of T2 were not (O1, O2, and O5), indicating that the oriT locus of Rts1 is located in the T2 segment.

The minimum region common to all the nine clones mapped to region IV, named region T2 (Fig. 2B), is 455 bp in size and located at positions 188398 to 188852. When the DNA fragment corresponding to region T2 was cloned into pUC18, the recombinant plasmid was mobilized, but plasmids containing fragments outside of T2 were not (Fig. 2A and 2B). This result confirmed that the oriT site of Rts1 is located in region T2. Region T2 roughly corresponds to the intergenic region between ORF251 and ORF252 and contains three inverted repeats. This somewhat resembles the common structure for oriT sequences (64).

Replication and maintenance systems.

Rts1 contains one replicon, consisting of the repA gene (ORF001), encoding a replication initiator protein, and the ori segment, containing several sequence elements characteristic of plasmid replicons that employ the iteron-based replication initiation and control mechanism (10, 31, 34, 67). The minimum segment for replication initiation defined by Itoh et al. (31), which contains duplicated dnaA boxes, four GATC sequences, and five 19-bp iterons, spans from position 51 to 238.

In Rts1, no partitioning system for stable maintenance was identified before, but a system highly similar to the parABS partitioning system of plasmid P1 was identified. ORF293 and ORF294 are highly homologous to ParA and ParB of P1, respectively, and are arranged in the same order as in P1 (1). Furthermore, a parS-like structure containing three copies of repeated sequence of 7 bp and an integration host factor binding motif were identified just downstream of ORF294 (11, 17). Although two additional ORFs, ORF190 and ORF273, also exhibited weak similarities to ParB of P1, they are not accompanied by parA-like genes. Rts1 contains a proteic killer system encoded by higBA (ORF261 and ORF262), which functions as a plasmid maintenance system (61, 62). The tdi locus could also be involved in the maintenance of Rts1 (48, 55). Thus, the stable maintenance of Rts1 is achieved by multiple systems.

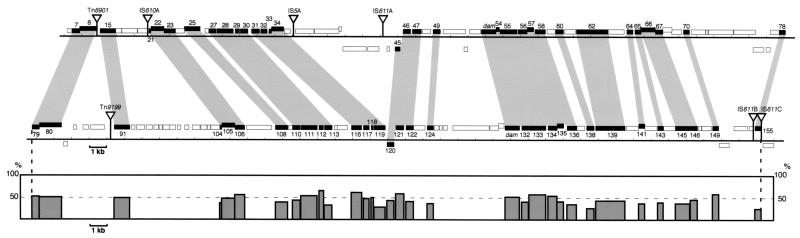

Large segment duplication on the Rts1 genome.

By examining the sequence similarity among all the gene products of Rts1, we identified 33 pairs of homologous genes which were located on the first 100-kb region of the Rts1 genome (Fig. 3). Genes comprising each pair are separately located in the first and the second halves of the 100-kb region, and the gene order is completely conserved. This finding indicates that the 100-kb region was created by a large segment duplication. Homology observed in each pair of genes is, however, not so remarkable (up to 65.6% amino acid sequence identity), implying that each subregion has undergone significant sequence diversification after duplication, and each pair of genes may have functionally diverged. In addition, the two subregions contain different sets of IS or transposon elements, and several genes or gene clusters seem to have been deleted or replaced after the duplication.

FIG. 3.

Large segment duplication in the Rts1 genome. The gene organization of the first and second halves of the 100-kb region of Rts1 (corresponding to modules M1a and M1b, respectively, in Fig. 4) is compared. Homologous genes are indicated by shading, and transposable genetic elements inserted in the regions are depicted by triangles. The homologous genes identified in each subregion are organized in the same order in both subregions. At the bottom, sequence similarities between each pair of homologous genes are presented (percent amino acid sequence identity). Levels of sequence conservation observed in each pair of homologous genes are not so high, implying that each gene has undergone significant sequence diversification after duplication.

Genes on the duplicated segments.

It is noteworthy that the duplicated segments encode many genes related to various kinds of DNA metabolisms, such as repair, recombination, restriction/modification, and replication (Fig. 1). Among these, the two copies of tus homologues (ORF015 and ORF091) are of particular interest, because no plasmid-borne tus gene has been reported so far, except that Koch et al. (35) recently identified a tus-like gene from R394, a close relative of Rts1. Tus dictates the arrest of replication progression by binding to a set of ter sequences (21, 22, 26) and plays a crucial role in replication termination of chromosomes (5, 23). Tus is also necessary for efficient replication termination in some plasmids, such as R6K and R1 (26, 37). These plasmid genomes contain ter consensus sequences but not the tus genes. Instead, the host-encoded Tus protein participates in the replication termination of these plasmids.

ORF015 and ORF091 of Rts1 both exhibit significant sequence similarity to the enterobacterial Tus proteins throughout the entire molecules. The sequences known to be essential for the Tus functions are well conserved (33), implying that both or either ORF015 and ORF091 encode Rts1-specific Tus proteins involved in the replication termination of Rts1. Because the 11-bp core sequence of the ter consensus (TGTTGTAACTA) is absent on the Rts1 genome, Rts1 Tus homologues must recognize different sequences.

ORF031 and ORF116 are highly homologous to the E. coli SSB protein (70% amino acid sequence identity over 147 residues and 84% over 113 residues, respectively). The ability of Rts1 to rescue the replication defect of an E. coli ssb mutant (18) could be explained by the presence of these ssb homologues. Rts1 contains another ssb homologue (ORF222) in the region between the two transfer gene clusters, but it is very distantly related to E. coli SSB (32% identity over 95 residues) and has an extremely long C-terminal tail, suggesting that it has some distinct function. ORF007/ORF008 and ORF079/ORF080 both encode UmuDC homologues, which mediate error-prone repair in the SOS repair system (51, 63). Although ORF008 is C-terminally truncated by the insertion of Tn6901, the other set of genes (ORF079/ORF080) appears to be intact and is probably responsible for the recently identified umu-complementing activity of Rts1 (35).

ORF053 and ORF131 are homologous to Dam methylase, which plays important roles in the initiation of replication and the sequestration of newly replicated oriC segments to the cell membrane (40). Both ORFs have been confirmed to possess Dam methylase activity by the SeqA focus formation experiment with the dam null mutant KA468 (24; T. Onogi and S. Hiraga, personal communication). Homologues of the beta and theta subunits of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme are also encoded (ORF050 and ORF081, respectively).

The gene for PvuRts1I, a T-even phage restriction enzyme, also resided in this region (corresponding to ORF063). In a previous study, an ORF encoding 290 amino acids was identified upstream of the PvuRts1I gene, but its protection activity relative to PvuRts1I was not detected (32). In this study, however, this ORF (ORF062) was found to actually encode a larger protein of 593 amino acids homologous to TraG1, a putative restriction methylase of plasmid R478. The function of this ORF needs to be reexamined with the possibility that it may have protection activity against PvuRts1I.

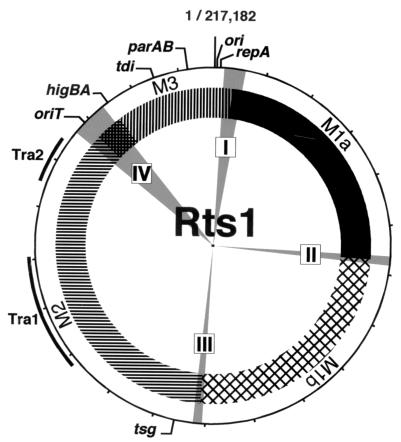

Genome organization and evolution of Rts1.

When the genome organization of Rts1 is overviewed, the genome can be considered to be composed of four modules (Fig. 4), two modules created by duplication (M1a and M1b), a transfer region-containing module (M2), and a module containing the genes required for replication and stable maintenance of Rts1 (M3). As for the large segment duplication, some site-specific recombination system might be involved in the event, because all the clones that formed cointegrates with Rts1 in the oriT screening were derived from three regions (regions I, II, and III), each corresponding to the predicted boundary of the duplicated segments. Since the oriT screening was performed in the recA mutant background, some site-specific recombination must mediate cointegrate formation. Rts1 encodes several genes related to the recombination function, and some of them might participate in cointegrate formation and segment duplication.

FIG. 4.

Circular representation of the Rts1 genome. Locations of modules M1a to M3, constituting the Rts1 genome, as well as regions I to IV that were identified in the oriT screening (see Fig. 2 and the text) are shown. Positions of transfer regions in module M2 and genes for replication and stable maintenance in module M3 are also indicated.

The boundary between the M2 and M3 modules is not precisely defined but seems to lie somewhere between oriT and higAB. It is noteworthy that Rts1 contains many homologues of the S. enterica serovar Typhi plasmid R27 genes. Among these, 26 exhibited highest similarities to the R27 genes in the homology search. Most of them resided on the M2 module (19 out of 26 genes). Rts1 and R27 in fact share a temperature-sensitive phenotype in conjugation transfer, but the high sequence similarity observed between the two plasmids is not limited to the genes for conjugation. This suggests that the M2 module has evolved from an ancestor common to that of R27. The similarity between the replication initiation systems of Rts1 and P1 had been noticed as well (2, 3, 34). It is now clear that their partitioning systems are also highly homologous. This finding further supports the evolutionary relationship of the two plasmids.

Concluding remarks.

Determination of the complete sequence of the large conjugative plasmid Rts1 provides several lines of important information on plasmid biology. All the genes potentially related to the conjugation function have been identified, which will facilitate comparative and experimental approaches to the full understanding of bacterial conjugation systems. An unexpected finding is the presence of multiple genes related to various types of DNA metabolism. They include plasmid-encoded tus homologues. The analysis of the genome organization of Rts1 provided a prominent example of the modular evolution of a large plasmid genome. The exchange or acquisition of modules from other replicons and the capture of IS elements and transposons are deeply involved in the generation of Rts1, as has been repeatedly discussed for plasmid genome evolution. In Rts1, however, another mechanism, the duplication of a large module and subsequent structural and functional diversification of the duplicated modules, has also played an important role in genome evolution and gene repertoire expansion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Itoh, A. Tabuchi, K. Tanimoto, M. Tsuda, and T. Komano for useful suggestions; K. Sato, M. Takahashi, and S. Setsu for technical assistance; and Y. Hayashi for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan and grants from the Yakult Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeles, A. L., S. A. Friedman, and S. J. Austin. 1985. Partition of unit-copy miniplasmids to daughter cells. III. The DNA sequence and functional organization of the P1 partition region. J. Mol. Biol. 185:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeles, A. L., L. D. Reaves, and S. J. Austin. 1990. A single DnaA box is sufficient for initiation from the P1 plasmid origin. J. Bacteriol. 172:4386-4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abeles, A. L., K. M. Snyder, and D. K. Chattoraj. 1984. P1 plasmid replication: replicon structure. J. Mol. Biol. 173:307-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A., Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, T. A. 1995. Replication arrest. Cell 80:521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borodovsky, M., and J. McIninch. 1993. GENEMARK: parallel gene recognition for both DNA strands. Comput. Chem. 17:123-133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley, D. E., and J. Whelan. 1985. Conjugation systems of incT plasmids. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:2665-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coetzee, J. N., N. Datta, and R. W. Hedges. 1972. R factors from Proteus rettgeri. J. Gen. Microbiol. 72:543-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couturier, M., F. Bex, P. L. Bergquist, and W. K. Maas. 1988. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 52:375-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, M. A., and S. J. Austin. 1988. Recognition of the P1 plasmid centromere analog involves binding of the ParB protein and is modified by a specific host factor. EMBO J. 7:1881-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiJoseph, C. G., M. E. Bayer, and A. Kaji. 1973. Host cell growth in the presence of the thermosensitive drug resistance factor, Rts1. J. Bacteriol. 115:399-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiJoseph, C. G., and A. Kaji. 1974. The thermosensitive lesion in the replication of the drug resistance factor Rts1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:2515-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenbrandt, R., M. Kalkum, E.-M. Lai, R. Lurz, C. I. Kado, and E. Lanka. 1999. Conjugative pili of IncP plasmids, and the Ti plasmid T pilus are composed of cyclic subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22548-22555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falkow, S., I. R. Ryman, and O. Washington. 1962. Deoxyribonucleic acid base composition of Proteus and Providencia organisms. J. Bacteriol. 83:1318-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Firth, N., K. Ippen-Ihler, and R. A. Skurray. 1996. Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation, p. 2377-2401. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, R., J. L. Ingraham, E. CC. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Funnell, B. E. 1988. Participation of Escherichia coli integration host factor in the P1 plasmid partition system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6657-6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golub, E. I., and K. B. Low. 1985. Conjugative plasmids of enteric bacteria from many different incompatibility groups have similar genes for single-stranded DNA-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 162:235-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goto, N., Y. Yoshida, Y. Terawaki, R. Nakaya, and K. Suzuki. 1970. Base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid of the temperature-sensitive kanamycin-resistant R factor Rts1. J. Bacteriol. 101:856-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haase, J., and E. Lanka. 1997. A specific protease encoded by the conjugative DNA transfer systems of IncP and Ti plasmids is essential for pilus synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 179:5728-5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hidaka, M., M. Akiyama, and T. Horiuchi. 1988. A consensus sequence of three DNA replication terminus sites on the E. coli chromosome is highly homologous to the terR sites of the R6K plasmid. Cell 55:467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill, T. M., A. J. Pelletier, M. L. Tecklenburg, and P. L. Kuempel. 1988. Identification of the DNA sequence from the E. coli terminus region that halts replication forks. Cell 55:459-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill, T. M. 1992. Arrest of bacterial DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:603-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiraga, S., C. Ichinose, H. Niki, and M. Yamazoe. 1998. Cell cycle-dependent duplication and bidirectional migration of SeqA-associated DNA-protein complexes in E. coli. Mol. Cell 1:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann, B., E. Strauch, C. Gewinner, H. Nattermann, and B. Appel. 1998. Characterization of plasmid regions of foodborne Yersinia enterocolitica biogroup 1A strains hybridizing to the Yersinia enterocolitica virulence plasmid. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horiuchi, T., and M. Hidaka. 1988. Core sequence of two separable terminus sites of the R6K plasmid that exhibit polar inhibition of replication is a 20 bp inverted repeat. Cell 54:515-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iida, S., J. Meyer, P. Linder, N. Goto, R. Nakaya, H.-J. Reif, and W. Arber. 1982. The kanamycin resistance transposon Tn 2680 derived from the R plasmid Rts1 and carried by phage P1Km has flanking 0.8-kb-long direct repeats. Plasmid 8:187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishaq, M., and A. Kaji. 1980. Mechanism of T4 phage restriction by plasmid Rts1. Cleavage of T4 phage DNA by Rts1-specific enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 255:4040-4047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishihara, M., Y. Kamio, and Y. Terawaki. 1978. Cupric ion resistance as a new genetic marker of a temperature-sensitive R plasmid, Rts1 in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 82:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itoh, Y., Y. Kamio, Y. Furuta, and Y. Terawaki. 1982. Cloning of the replication and incompatibility regions of a plasmid derived from Rts1. Plasmid 8:232-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh, Y., Y. Kamio, and Y. Terawaki. 1987. Essential DNA sequence for the replication of Rts1. J. Bacteriol. 169:1153-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janosi, L., H. Yonemitsu, H. Hong, and A. Kaji. 1994. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel hydroxymethylcytosine-specific restriction enzyme (PvuRts1I) modulated by glucosylation of DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 242:45-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamada, K., T. Horiuchi, K. Ohsumi, N. Shimamoto, and K. Morikawa. 1996. Structure of a replication-terminator protein complexed with DNA. Nature 383:598-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamio, Y., A, Tabuchi, Y. Itoh, H. Katagiri, and Y. Terawaki. 1984. Complete nucleotide sequence of mini-Rts1 and its copy mutant. J. Bacteriol. 158:307-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch, W. H., A. R. Fernandez de Henestrosa, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Identification of mucAB-like homologs on two IncT plasmids, R394 and Rts1. Mutat. Res. 457:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komano, T., T. Yoshida, K. Narahara, and N. Furuya. 2000. The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1348-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krabbe, M., J. Zabielski, R. Bernander, and K. Nordstrom. 1997. Inactivation of the replication-termination system affects the replication mode and causes unstable maintenance of plasmid R1. Mol. Microbiol. 24:723-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamark, T., I. Kaasen, M. W. Eshoo, P. Falkenberg, J. McDougall, and A. R. Strøm. 1991. DNA sequence and analysis of the bet genes encoding the osmoregulatory choline-glycine betaine pathway of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1049-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanka, E., and B. M. Wilkins. 1995. DNA procession reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:141-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marinus, M. G. 1996. Methylation of DNA, p. 782-791. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, R., J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 41.Matsumoto, H., Y. Kamio, R. Kobayashi, and Y. Terawaki. 1978. R plasmid Rts1-mediated production of extracellular deoxyribonuclease in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 133:387-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Missiakas, D., C. Georgopoulos, and S. Raina. 1994. The Escherichia coli dsbC (xprA) gene encodes a periplasmic protein involved in disulfide bond formation. EMBO J. 13:2013-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mochida, S., H. Tsuchiya, K. Mori, and A. Kaji. 1991. Three short fragments of Rts1 DNA are responsible for the temperature-sensitive growth phenotype (Tsg) of host bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 173:2600-2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mollet, B., M. Clerget, J. Meyer, and S. Iida. 1985. Organization of the Tn6-related kanamycin resistance transposon Tn2680 carrying two copies of IS26 and an IS903 variant, IS903B. J. Bacteriol. 163:55-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murata, T., A. L. Bognar, T. Hayashi, M. Ohnishi, K. Nakayama, and Y. Terawaki. 2000. Molecular analysis of the folC gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:879-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakayama, K., S. Kanaya, M. Ohnishi, Y. Terawaki, and T. Hayashi. 1999. The complete nucleotide sequence of φCTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 31:399-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okawa, N., M. Tanaka, S. Finver, and A. Kaji. 1987. Identification of the Rts1 DNA fragment responsible for temperature-sensitive growth of host cells harboring a drug resistance factor Rts1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 142:1084-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okawa, N., H. Yoshimoto, and A. Kaji. 1985. Identification of an Rts1 DNA fragment conferring temperature-dependent instability to vector plasmids. Plasmid 13:88-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pohlman, R. F., F. Liu, L. Wang, M. I. More, and S. C. Winans. 1993. Genetic and biochemical analysis of an endonuclease encoded by the IncN plasmid pKM101. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4867-4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raina, S., and D. Missiakas. 1997. Making and breaking disulfide bonds. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:179-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reuven, N. B., G. Arad, A. Maor-Shoshani, and Z. Livneh. 1999. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB and is specialized for translesion replication. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31763-31766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romine, M. F., L. C. Stillwell, K.-K. Wong, S. J. Thurston, E. C. Sisk, C. Sensen, T. Gaasterland, J. K. Fredrickson, and J. D. Saffer. 1999. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181:1585-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 54.Sherburne, C. K., T. D. Lawley, M. W. Gilmour, F. R. Blattner, V. Burland, E. Grotbeck, D. J. Rose, and D. E. Taylor. 2000. The complete DNA sequence and analysis of R27, a large IncHI plasmid from Salmonella typhi that is temperature-sensitive for transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2177-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka, M., N. Okawa, K. Mori Y. Suyama, and A. Kaji. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of an Rts1 fragment causing temperature-dependent instability. J. Bacteriol. 170:1175-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terawaki, Y., H. Takayasu, and T. Akiba. 1967. Thermosensitive replication of a kanamycin resistance factor. J. Bacteriol. 94:687-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terawaki, Y., Y. Kakizawa, H. Takayasu, and M. Yoshikawa. 1968. Temperature sensitivity of cell growth in Escherichia coli associated with the temperature-sensitive R (KM) factor. Nature 219:284-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terawaki, Y., and R. Rownd. 1972. Replication of the R factor Rts1 in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 109:492-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terawaki, Y., Y. Kobayashi, M. Matsumoto, and Y. Kamio. 1981. Molecular cloning and mapping of a deletion derivative of the plasmid Rts1. Plasmid 6:222-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tian, Q. B., T. Hayashi, T. Murata, and Y. Terawaki. 1996. Gene product identification and promoter analysis of hig locus of plasmid Rts1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 225:679-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian, Q. B., M. Ohnishi, A. Tabuchi, and Y. Terawaki. 1996. A new plasmid-encoded proteic killer gene system: cloning, sequencing, and analyzing hig locus of plasmid Rts1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 220:280-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tian, Q. B., M. Ohnishi, T. Murata, K. Nakayama, Y. Terawaki, and T. Hayashi. 2001. Specific protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction in the hig gene system, a plasmid-borne proteic killer gene system of plasmid Rts1. Plasmid 45:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker, G. C. 1996. The SOS response of Escherichia coli, p. 1400-1416. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, R., J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 64.Wilkins, B., and E. Lanka. 1993. DNA processing and replication during plasmid transfer between gram-negative bacteria, p. 105-136. In D. B. Clewell (ed.), Bacterial conjugation. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 65.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yokota, T., Y. Kanamaru, R. Mori, and T. Akiba. 1969. Recombination between a thermosensitive kanamycin resistance factor and a nonthermosensitive multiple-drug resistance factor. J. Bacteriol. 98:863-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yonemitsu, H., H. Higuchi, T. Fujihashi, and A. Kaji. 1995. An unusual mutation in RepA increases the copy number of a stringently controlled plasmid (Rts1 derivative) by over one hundred fold. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:397-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarembinski, T. I., L.-W., Hung, H.-J. Mueller-Dieckmann, K.-K. Kim, H. Yokota, R. Kim, and S.-H. Kim. 1998. Structure-based assignment of the biochemical function of a hypothetical protein: a test case of structural genomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15189-15193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]