Abstract

Activation of cytotoxic nucleoside analogs in vivo depends primarily on their cell-specific phosphorylation. Anticancer chemotherapy using nucleoside analogs may be significantly enhanced by intracellular administration of active phosphorylated drugs. However, the cellular transport of anionic compounds is very ineffective and restricted by many drug efflux transporters. Recently developed cationic nanogel carriers can encapsulate large amounts of nucleoside 5′-triphosphates that form polyionic complexes with protonated amino groups on the polyethylenimine backbone of the nanogels. In this paper, 5′-triphosphate of an antiviral nucleoside analog, 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT), was efficiently synthesized and its complexes with nanogels were obtained and evaluated as potential cytotoxic drug formulations for treatment of human breast carcinoma cells. A selective phosphorylating reagent, tris-imidazolylphosphate, was used to convert AZT into the nucleoside analog 5′-triphosphate using a one-pot procedure. The corresponding 3′-azidothymidine 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP) was isolated with high yield (75%). Nanogels encapsulated up to 30% of AZTTP by weight by mixing solutions of the carrier and the drug. The AZTTP/nanogel formulation showed enhanced cytotoxicity in two breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, demonstrating the IC50 values 130–200 times lower than those values for AZT alone. Exact mechanism of drug release from nanogels remains unclear. One mechanism could involve interaction with negatively charged counterions. A high affinity of nanogels to isolated cellular membranes has been observed, especially for nanogels made of amphiphilic block copolymer, Pluronic® P85. Cellular trafficking of nanogel particles, contrasted by PEI-coordinated copper(II) ions, was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which revealed membranotropic properties of nanogels. A substantial release of encapsulated drug was observed following interactions of drug-loaded nanogels with cellular membranes. A drug release mechanism triggered by interaction of the drug-loaded nanogels with phospholipid bilayer is proposed. The results illustrate therapeutic potential of the phosphorylated nucleoside analogs formulated in nanosized crosslinked polymeric carriers for cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: nanogels, 3′-azidothymidine 5′-triphosphate, synthesis, cytotoxicity, membrane, cellular trafficking, cancer

Introduction

Nucleoside analogs represent an important class of anticancer chemotherapeutics 1,2. These compounds are actually ‘prodrugs’ that require initial conversion to active 5′-phosphorylated nucleosides by intracellular nucleoside kinases. This enzymatic phosphorylation progresses in three steps: first nucleoside 5′-monophosphate (NMP), second, 5′-diphosphate (NDP) and, finally, nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTP). The 5′-triphosphates of cytotoxic nucleoside analogs are efficient terminators of nucleic acid synthesis in proliferating cancer cells. However, these compounds are considered to be too unstable for direct use in cancer chemotherapy. Various approaches have been evaluated to prepare stable in serum phosphate analogs of NTP, however, they could not significantly improve the situation 3,4. Recently, nucleoside analogs have been more frequently administered in the form of more soluble nucleoside 5′-monophosphates or their protected prodrug derivatives 5. Development of drug resistance due to a decreased nucleoside kinase activity has often reduced the efficacy of nucleoside analogs 6. Used in chemotherapy, high therapeutic doses caused many adverse effects in vivo and usually were attributed to inefficient activation of these drugs. Transporter mechanisms of nucleoside drug delivery and efflux, and associated drug resistance has been discovered in many cancer cells and demonstrated recently for different nucleoside analogs 2. The high electronegative nature of NTP makes their mass transport across cellular barriers an extremely difficult event. First, these charges should be neutralized by counterions, and second, NTPs should be protected from phosphatase activities in the biological environment. The application of nano- or microcarriers for encapsulation and targeted delivery of phosphorylated nucleoside drugs will allow resolve many of the problems associated with this chemotherapy. Until now, there was only a handful of successful examples for encapsulation and cellular delivery of phosphorylated nucleoside drugs in liposomes 7–9 or erythrocytes 10–12.

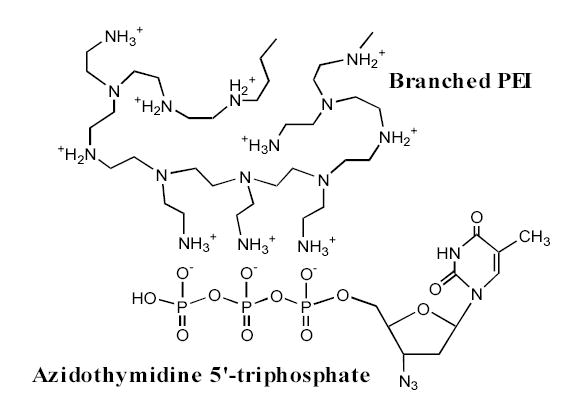

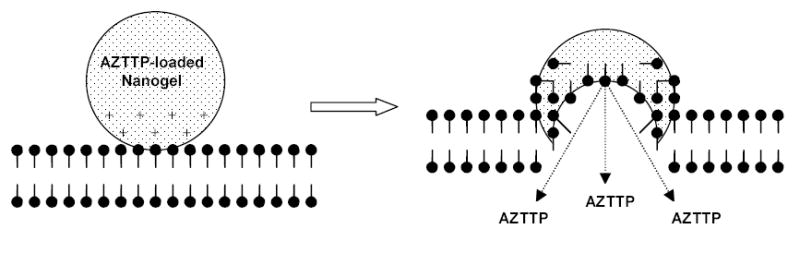

The last few years have witnessed intense development in the area of polymeric drug delivery systems 13. One of the most interesting cationic polymers used in the area of drug delivery is polyethylenimine (PEI). PEI was first introduced a decade ago as an efficient non-viral transfection agent 14. Branched PEI has a very high density of positive charges and can be easily modified with polymers or targeting ligands 15,16. We have a long-standing interest in the development of PEI-based carriers, such as PEI-graft-conjugates with PEG or block copolymers (Poloxamers) 17–20, or corresponding cross-linked polymeric networks (nanogels) 21,22. In this manuscript we suggest a new drug formulation based on the nucleoside analog 5′-triphosphate encapsulated into a nanosized hydrophilic polymeric network - nanogel. Negatively charged phosphate groups of NTP form polyionic complexes with protonated amino groups of PEI chains in nanogels as shown in Figure 2. Recently, our preliminary data have demonstrated an efficient drug encapsulation, protection against enzymatic degradation, and targeted delivery of NTP-loaded nanogels into cancer cells 23. These formulations of nucleoside analogs, administered at lower doses, have shown a strong cytotoxic effect on cancer cells. The purpose of the present study was to prepare 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP), its formulation with nanogels, and to evaluate the membranotropic affinity of drug-loaded nanogel particles. This property may play a critical role in the cellular accumulation of AZTTP-loaded nanogels and intracellular release of the active phosphorylated drug from carrier. Cellular uptake of AZTTP-encapsulated nanogels was very efficient, and this formulation has induced death of human breast carcinoma cells at significantly lower doses compared to the original nucleoside analog. Our results suggest that interaction of drug-loaded nanogels with cells or cellular membranes results in a triggered drug release from nanogel carriers into cytosol.

Figure 2.

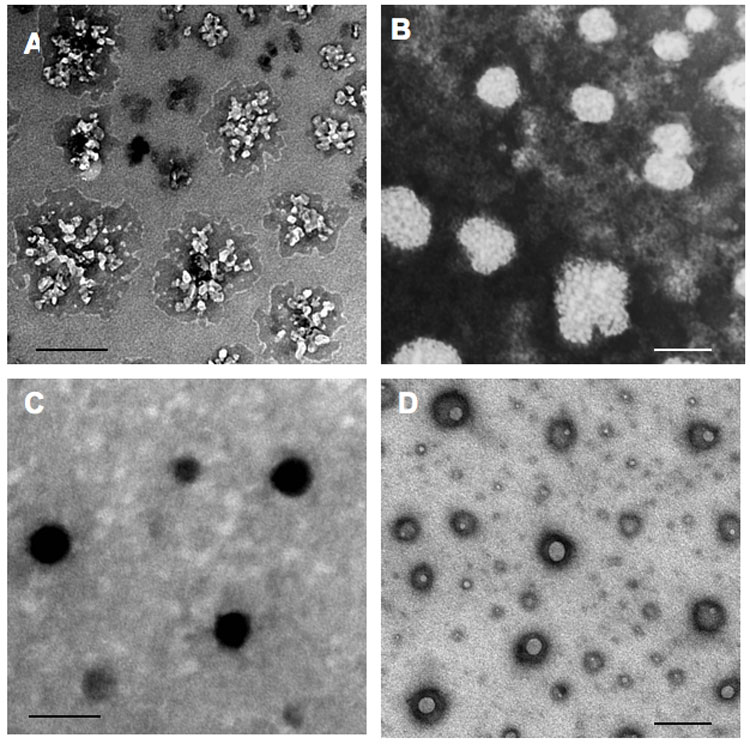

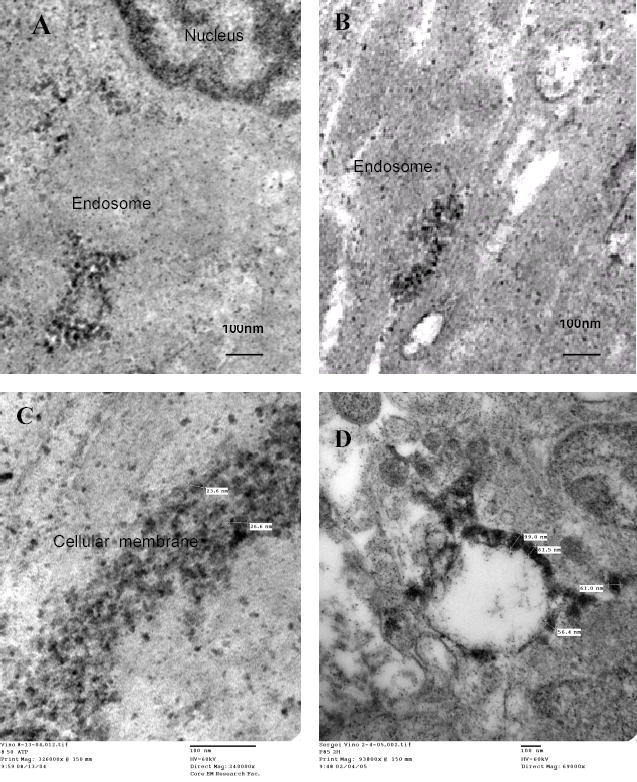

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of Nanogels, NG(PEG) (A) and NG(P85) (B), contrasted by copper(II) ions. ATP-loaded NG(PEG) (C) and NG(P85) (D) form compact ATP-PEI complexes with a dense core. Bars: 100 nm.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods.

All solvents and reagents, except specially mentioned, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) at the highest purity grade. Pluronic® P85 was a gift from BASF Corp. (Parsippany, NJ). 3H-Succinimidyl propionate, specific activity 40Ci/mmol, was purchased from ARC, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). BODIPY® FL ATP was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). SpectraPor dialysis membrane tubes with various MW cutoffs were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Nanogel Synthesis and Labeling.

Synthesis of nanogels consisting of a PEG-cl-PEI polymeric network, NG(PEG), was described previously 24, and this protocol was used with minor modifications for the synthesis of nanogels with Pluronic® P85-cl-PEI polymeric network, NG(P85). Both hydroxyl groups at the ends of Pluronic® P85 have been activated by reaction with 5-fold molar excess of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole. The bis(imidazolylcarbonyl)ated Pluronic® P85 was isolated using dialysis (MWCO 2,000 Da) against 10% ethanol, twice for 4 h at 4°C. The activated product was freeze dried and dissolved in dichloromethane, 20% (w/v). Commercial PEI was purified by dialysis (MWCO 2,000 Da and MWCO 25,000 Da) against water for 48 h at 25°C; fraction with MW <25,000 Da was collected and concentrated in vacuo. Solution of the activated Pluronic® P85 (15 mL) was added dropwise to 250 mL of 0.4% aqueous PEI solution, followed by sonication in an ultrasonic water bath, mixing for 10 min, and removal of organic solvent in vacuo at 50°C. “Maturation” of nanogel particles was continued overnight at 25°C, and large debris was removed by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 30 min. The solution was dialyzed (MWCO 12,000 Da) against 0.025% aqueous ammonia containing 10% ethanol for 24 h at 25°C to remove polymers with low-molecular weight, concentrated in vacuo, and freeze-dried to obtain nanogels NG(P85) with 50% yield by weight.

For the analysis of polymer/PEI molar ratios in nanogel preparations, 5% solutions of dried samples in D2O were prepared and filtered. 1H NMR spectra (with integration) were obtained in the range 0–6 ppm at ambient temperature using a Varian 300 MHz spectrometer. These data have been used to calculate a polymer/PEI molar ratio in obtained nanogels. Elemental analysis (M-H-W Laboratories, Phoenix, AZ) was used to determine the total nitrogen content and a polymer/PEI weight ratio in nanogels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition and properties of nanogels

| Nanogel type | PEO: CH2O, δ (Integral, %) | PPO: CH3, δ (Integral, %) | PEI: CH2N, δ (Integral, %) | Molar (weight) Polymer: PEI ratio* | Average diameter, nm (+AZTTP)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG(PEG) | 3.56 (72.9) | – | 2.52–2.68 (27.1) | 8.3 (2.7) | 301±6 (150±4) |

| NG(P85) | 3.56 (63.6) | 1.05 (8.2) | 2.56–2.76 (28.2) | 18.1 (3.3) | 297±4 (144±3) |

Based on 1H-NMR and elemental analysis data;

Data for major unfractionated batches of nanogels or nanogel/AZTTP formulations prepared on their basis and dispersed in phosphate buffer at concentration 0.1 mg mL−1.

In order to modify nanogels with a fluorescent dye, the polymeric carrier (100 mg) was dispersed in 1 mL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9, and treated with 1% solution of rhodamine isothiocyanate (RITC) (0.1 mL) in dimethylformamide (DMF) overnight at 25°C. The red colored fraction consisting of rhodamine-labeled nanogel was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration in 20% ethanol twice using disposable NAP-25 columns (Amersham-GE Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Fractions containing the fluorescent nanogel product were lyophilized with 80% recovery. Fluorescent spectral characteristics of the rhodamine-labeled nanogel (λex 549 nm and λem 577 nm) were measured in the phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using spectrofluorimeter.

Tritium-labeled nanogels were synthesized as follows 22. Suspension of nanogel (0.2 g) in 2 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile containing 2% (v/v) of triethylamine was treated with a solution of 3H-succinimidyl propionate (100 μCi) in toluene-ethyl acetate mixture overnight at 25°C. Organic solvents were removed using a stream of nitrogen, and tritium-labeled nanogel was separated from low molecular weight substances by gel filtration on the Sephadex G-25 column (1 x 20 cm) in 20% ethanol at elution rate 0.5 mL min−1. Radioactivity of the fractions was measured using a liquid scintillation counter. Efficiency of the labeling procedure was no less than 80%. Fractions containing the labeled nanogel have been collected and lyophilized. The specific activity of the tritium-labeled nanogel measured in 0.01% aqueous solution was 0.8 μCi/mg.

Synthesis of AZT 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP).

3′-Azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) was phosphorylated using a one-pot synthesis. The phosphorylating agent, tris-imidazolylphosphate, was synthesized according to the following modification of a previously described procedure 25,26. Trimethylsilylimidazole (2.3 g, 15.5 mmol) in 25 mL of anhydrous toluene was treated dropwise with freshly distilled phosphorus oxychloride (0.77 g, 5 mmol) under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h at 25°C and then concentrated in vacuo until white solid crystals formed. The process was continued at −18°C for 3 h and crystals were decanted and washed with cold toluene. The product was dried overnight in vacuo over phosphorus pentoxide. The white solid reagent, tris-imidazolylphosphate, was obtained with a yield of 97%.

Azidothymidine (267 mg, 1 mmol) was dried by coevaporation twice with anhydrous toluene (15 mL) followed by addition of tris-imidazolylphosphate (500 mg, 2 mmol) in 2 mL of anhydrous DMF. The mixture was allowed to stand for 3 h at 25°C, quenched with 0.2 mL of methanol at 4°C, incubated for 30 min at 25°C, and added dropwise to a solution of tetra-n-butylammonium salt of inorganic pyrophosphate (1.2 g, 2.7 mmol) in 4 mL of DMF containing 0.5 mL (2.8 mmol) of N,N’-diisopropylethylamine. The clear reaction mixture was mixed for 24 h at 25°C, and then the phosphorylated products were precipitated by the addition of 200 mL of 1% sodium perchlorate in cold acetone. A white precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed 2 times with cold acetone, and dried in vacuo. The product was incubated in 25% aqueous ammonia overnight at 4°C and then concentrated in vacuo. Analytical HPLC showed that the conversion rate of the nucleoside analog into 5′-triphosphate was usually higher than 85%. This product was purified on a Sephadex QAE A-25 (5x15 cm) column in 0.1M triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), pH 8, containing 20% ethanol, at elution rate 4 mL min−1. The column was washed with a stepwise gradient of TEAB concentrations: 250 mL-volumes of 0.1M, 0.15M, 0.2M, 0.25M and 750 mL of 0.25M TEAB to elute the major peak of AZTTP. The product was lyophilized, precipitated with sodium perchlorate in acetone as described above, and dried in a vacuum desiccator. AZTTP was isolated with a total yield of 75% (purity >90%). Analysis of 5′-phosphorylated nucleosides was performed by ion-pair HPLC (Vydac C18 column, 0.4 x 15 cm), eluting with 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 6, 0.15% tetrabutylammonium chloride at 1 mL min−1 in the concentration gradient of acetonitrile (0–30%) 27. Retention times were 3.9 min (nucleoside, AZT), 7.3 min (5′-monophosphate, AZTMP), 10 min (5′-diphosphate, AZTDP) and 12.8 min (5′-triphosphate, AZTTP).

Elemental analysis of AZTTP was close to theoretically calculated values for tetrasodium salt of AZTTP: C10H12N5O13P3Na4 , calcd: C 20.16, H 2.02, N 11.76, O 34.95, P 15.63, Na 15.46 and found: C 20.21, H 2.04, N 11.99, O 35.11, P 15.85, Na 14.80.

Enzymatic hydrolysis was used to confirm the polyphosphate structure of AZTTP. 0.2, 0.5 or 1 units of alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1, small intestine, 200 units mL−1) were added to 90 qL of a 5 mM solution of AZTTP in 0.1M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, and 2 mM MgCl2 and incubated for 60 min at 25°C. The degradation products, AZT and its phosphates, were analyzed by ion pair HPLC as described above.

Formulation of nanogels with AZTTP.

Nanogels were used in free amine form. The tetrasodium salt of AZTTP was dissolved in water and passed through a short Dowex-50 x 6 column in H+ form to convert the 5′-triphosphate into the free acid form. The column was then washed by water (2 x 15 mL), and the collected eluate was used directly for titration of the nanogel solution until pH of the mixture reached 7.4. The final complex was freeze-dried and stored in dry form in the freezer at −20°C. At these conditions nanogel/AZTTP complexes contained up to 30% (wt) of the encapsulated AZTTP as determined spectrophotometrically by absorbance at 267 nm (ɛ = 11,650).

Measurements of nanogel diameters by dynamic light scattering were performed using a ‘ZetaPlus’ Zeta Potential Analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with 15 mV solid state laser operated at a laser wavelength of 635 nm and having the Multi-Angle Option at the angle of 90°. Effective hydrodynamic diameters of free and the AZTTP-loaded nanogel particles were measured at 25°C in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at concentration 0.1 mg mL−1.

Nanogel Binding with Isolated Cellular Membranes.

Crude cellular membranes were isolated according to the previously described protocol 28. About 2 x 108 harvested MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells were washed by ice cold PBS and centrifuged at 1200x g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet (1 x 107 cells mL−1) was suspended in hypotonic lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, and incubated for 1 h on ice. The swollen cells were disrupted with 20 strokes in Dounce homogenizer. The nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 400x g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 1 h, and the pellet was used as a crude membrane fraction. The membrane fraction was analyzed for protein content using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay, resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer containing 50% (w/v) glycerol and stored at −80°C.

In the membrane-binding experiments, 10 μL of tritium-labeled nanogel (70 μg) was added to 0.5 mL-aliquot of isolated membranes (1 mg of protein content), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for different time points (30 min, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h). After incubation, the sample was collected at 12,000 x g to separate unbound nanogels. The resulting membrane pellet was dissolved in PBS, and 10 μL of the solution was used for radioactive counting. All incubations were done in triplicate.

For the in vitro drug release experiment, the prepared 0.01% solution of drug-nanogel complex was divided into two equal parts, and cellular membranes were added (1 or 2 mg of protein mL−1) to one. The samples were added to dialysis tubes (MWCO 2,000 Da) and dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4). At indicated time points, approximately 50μl of the sample was removed from the dialysis bag and diluted 20-fold to determine absorbance at 260nm. The graphs were plotted as % of drug release from the complex vs. time.

Cells and Cell Culture.

Human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD), and MDA-MB-231 cells were a gift from Dr. Rakesh Singh (UNMC). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All culture media were obtained from Gibco Life Technologies, Inc. For cytotoxicity and accumulation studies, cells were seeded at densities of 5,000 cells/well in 96-well microplates or 50,000 cells/well in 24-well microplates.

Cytotoxicity studies.

Cytotoxicity of nanogels, free nucleotides or nucleotide-loaded nanogels was measured in the cell viability assay using 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) 29. Briefly, 96-well microplates were seeded with 5000 cells/well and allowed to attach overnight. Serial dilutions of nanogels, free nucleotides or drug-nanogel formulations in fresh culture medium were incubated with the cells for 24 h at 37°C. The cells were washed with 3 x 0.1 mL of DMEM and grown for 3 days in 0.2 mL of fresh full culture medium changed daily. Then, 25 μL of MTT solution (5 mg mL−1) was added and cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in the dark. After washing, the cells were lysed with 20% sodium dodecylsulfate in 50% aqueous DMF (100 μL) overnight at 37°C. Absorption was measured at 550 nm in a microplate reader and expressed as a percentage of the values obtained for control cells treated only with culture medium. All measurements were repeated eight times.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

In order to prepare electron-contrasted particles, a nanogel suspension (1 mg mL−1) was mixed with 1 mM Cu(NO3)2 in 10 mM tris buffer, pH 7.4, and 0.1M NaCl at the molar cupper/PEI ratio 10, which is equivalent to about 10% of PEI saturation by cupper(II) cations. A 2-fold excess of an ATP solution was added 30 min later and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 25°C to obtain nanogel/ATP complexes. An excess of ATP was removed by dialysis (MWCO 2,000 Da) for 4 h against water and the complexes were freeze-dried. The cultured cancer cells have been treated with 0.01% solutions of nanogels in serum-free medium. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, washed twice with PBS, and fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 h. After removal of the fixative, cells were placed in PBS containing 1% BSA, scraped and spinned. The collected pellets were stored in this solution at 4°C before processing. Plastic-embedded samples for TEM were prepared and examined as described previously using a Philips 410LS transmission electron microscope equipped with an AMT digital imaging system (UNMC Electron Microscopy Core) 30.

Atomic Force Microscopy.

The following protocol for the Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was employed to observe the interaction of different types of nanogels, NG(PEG) or NG(P85), with isolated cellular membranes. Cellular membrane aliquots equivalent to 0.1 mg mL−1 of protein were pre-incubated with nanogel solution (0.1 mg mL−1) for 2 h at 37°C. After incubation, 100qL of the mixture was placed on a 1 cm2 piece of freshly cleaved mica. An excess of liquid was removed in 20 min by a stream of argon. The sample was placed in microscope and imaged on air immediately. All measurements were performed in amplitude mode on MFP instrument (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Images were taken on air at 25°C using the Asylum Research AC160TS tip (UNMC Molecular Imaging Core).

Laser Confocal Microscopy.

Formulations of nanogels with fluorescent drug, ATP-BODIPY, have been prepared as described above. Cellular accumulation of rhodamine-labeled nanogels and drug-nanogel formulations was examined in live MCF-7 cells without cell fixation as follows. MCF-7 cells were plated in Bioptech® plates (Bioptechs, Butler, PA) at a density of 50,000 cells per plate (50% confluency) in 0.8 mL of growth medium and allowed to attach for 24 h prior to the treatment. Cells were washed briefly with 0.5 mL of assay buffer and then incubated with 1 mL of 0.001% nanogel or drug-nanogel formulations for specified time periods in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Thereafter, cells were washed three times with 0.5 mL ice-cold PBS containing 1% BSA and, finally, once with solely ice-cold PBS, and investigated at two fluorescence modes, for rhodamine and BODIPY FL dyes. Zeiss Confocal LSM410 microscope (Iena, Germany) equipped with an argon-krypton laser was used to study the intracellular trafficking of the nanogel (UNMC Confocal Microscopy Core).

Results

Synthesis of Nanogel Carriers.

Swollen nanosized polymeric network of nanogels have been prepared by crosslinking of branched PEI (MW 25,000) with bis-imidazolcarbonyloxy-derivatives of PEG (MW 8,000) or amphiphilic block copolymer, Pluronic® P85 (MW 4,600) in a heterogeneous system using an “emulsification-solvent evaporation” method as described previously 24. Crude fractionation of the obtained nanogels could be performed by preparative gel-permeation chromatography. High degree of cross-linking was obtained for nanogel networks with a polymer/PEI molar ratio ranging from 8 to 18 (Table 1). Urethane bonds between PEI and neutral polymers in nanogels are hydrolytically stable; however, protonation of the PEI molecules in nanogels results in a gradual hydrolysis of urethane bonds and ultimate degradation of the nanogel network after several days of incubation under physiological conditions. Both types of nanogels, NG(PEG) and NG(P85) consisted of polydispersed particles, with diameters between 100 and 300 nm (Figure 3). Polymer chains in NG(PEG) and NG(P85) were uniformly distributed and formed particles with well-developed surface staining by PEI-coordinated copper(II) cations (Figures 2A and 2B). Addition of nucleoside 5′-triphosphate to the NG(PEG) nanogels resulted in significant compaction of the nanogel network into particles with dense electron-contrasted cores (Figure 2C). By contrast, the NTP-loaded NG(P85) nanogels showed compactly-looking particles with donut-like shapes (Figure 2C). Intracellular trafficking of these particles could be easily traced using TEM.

Figure 3.

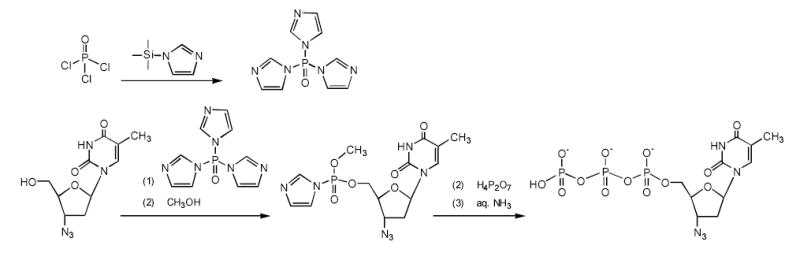

One-pot synthesis of a 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine 5′-triphophate (AZTTP). The phosphorylating reagent, tris-imidazolylphosphate, is prepared as a crystalline solid from the phosphoryl chloride and N-trimethylsilyl-imidazole in toluene. Initially, AZT reacts with this phosphorylating reagent (1), and then with methanol (2), forming an intermediate product, AZT 5′-imidazolylmethylphosphate. This activated product is converted into AZTTP following the reaction with tetra-n-butylammonium salt of pyrophosphate (3) and isolated by anion-exchange chromatography (4).

Synthesis of 3′-Azidothymidine 5′-Triphosphate.

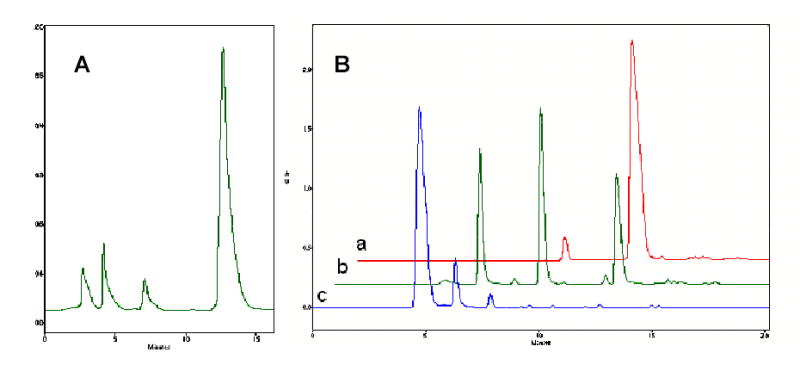

Chemical synthesis of a nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTP) could be performed in several steps, including transient protection of nucleosides and chromatographic isolation of intermediate products. Generally, NTP preparation is a costly process where final yields do not exceed 40–50% 31. Alternative, inexpensive one-pot conversion of nucleosides into 5′-triphosphate with single chromatographic purification of the NTP product could be applied for pyrimidine nucleoside analogs without 2′ and 3′-hydroxyl groups. We have developed an improved modification of the one-pot approach that allowed us to synthesize a hundred milligrams of 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP) (Figure 4). According to this method, a primary 5′-hydroxyl group of AZT was efficiently and specifically phosphorylated with the mild phosphorylating reagent, tris-imidazolylphosphate (TIP). TIP primarily phosphorylated the 5′-hydroxyl group and, with low efficacy, the 3′-hydroxyl group of nucleosides. However, nucleoside analogs with no 3′(2′)-hydroxyl groups could be converted into the NTP without complications. Previously, we synthesized a similar phosphorylating reagent, tris-triazolylphosphate using reaction of N-trimethylsilyltriazole with phosphoryl chloride 26. This reaction was very efficient and produced the phosphorylated reagent in solid crystalline form. However, this reagent was later found to be exceedingly active, modifying the heterocyclic bases of nucleosides as well. We have obtained the TIP using a reaction of phosphoryl chloride with N-trimethylsilylimidazole in anhydrous toluene. The trimethylsilyl chloride formed during this reaction was eliminated by evaporation in vacuo, and the crystalline TIP reagent was precipitated from the cold saturated solution. AZT was reacted initially with the phosphorylated reagent as shown in Figure 4. The nucleotide 5′-imidazolylphosphates could readily interact with inorganic pyrophosphate forming nucleoside 5′-triphosphates 32. Introduction of methanol significantly reduced the amount of by-products in this synthesis. The obtained phosphorylated intermediate II was reacted without isolation with tetra-n-butylammonium salt of inorganic pyrophosphate at 25°C and the reaction product after mild ammonia treatment represented mainly nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP) by HPLC analysis (Figure 4A). It was purified by preparative anion exchange chromatography with high yields and purity >90% (Figure 4B, line a). The structure of AZTTP was confirmed by elemental analysis of its sodium salt, as well as by partial hydrolysis with alkaline phosphatase and HPLC analysis of degradation products (Figure 4B, lines b–c).

Figure 4.

Ion-pair HPLC analysis of reaction mixtures after synthesis of the AZT 5′-triphosphate (A) and after enzymatic hydrolysis of purified AZTTP (B, line a) with different concentrations of alkaline phosphatase (lines b and c). AZT was eluted at t = 5 min, AZTMP – at t = 7.3 min, AZTDP - at t = 10 min AZTTP at t = 13 min.

Properties of Nanogel-Nucleotide Complexes.

Nanogel-nucleotide complexes form spontaneously by titration of nanogel carriers in the form of free amines with a solution of AZTTP in the form of free acid form up to pH 7.4. Small molecules of nucleoside 5′-triphosphates easily penetrate into the inner volume of swollen nanogels, associate with protonated amino groups of PEI and result in collapse of the neutralized cross-linked polymeric network (Figure 2). The change in size of the polyionic complexes was studied using a dynamic light scattering technique. We observed a significant size reduction of loaded carriers compared to original nanogels, which was equivalent to ca. a 10-fold decrease of nanogel volume. The hydrodynamic radius of AZTTP/nanogel complexes at 0.01% concentration was ~150 nm (Table 1). All complexes showed negligible surface positive charge (zeta-potential) because of the shielding effect of neutral PEG chains, which form a protective polymeric envelope surrounding nanogels. The compaction was previously demonstrated to increase resistance of drug-nanogel formulations to degradation by nucleolytic enzymes in biological media 23. Nanogel formulations had a high AZTTP-loading capacity reaching up to 0.5 μmol mg−1, or 30% by weight. Drug-loaded nanogels showed no signs of aggregation (particle size increase) during prolonged incubation in biological media with or without serum at 25 or 37°C. The drug-nanogel formulations could be stored in freeze-dried form and redissolved without significant changes in particle size (data not shown). These complexes have provided an excellent protection of encapsulated NTP against enzymatic degradation in vitro (Table 2). At conditions, when most of the free AZTTP was hydrolyzed to AZT (26%) and AZTMP (67%), AZTTP/nanogel formulation has protected up to 60% of AZTTP, forming 4 times less AZT and AZTMP metabolites.

Table 2.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of AZT 5′-triphosphate and its nanogel formulation

| Nucleoside and nucleoside 5′-phosphates content (%) in formulations:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | drug | drug + enzyme* | Drug/nanogel | Drug/nanogel + enzyme* |

| AZTTP | 90 ± 3 | 0 | 93.5 ± 0.8 | 58 ± 2.5 |

| AZTDP | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 7 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 19.8 ± 1.1 |

| AZTMP | 0 | 66.8 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 2 |

| AZT | 0 | 26 ± 1 | 0 | 6.1 ± 0.1 |

Intestinal alkaline phosphatase (0.5 U, 37° C, 1h).

Cytotoxicity of Nanogel Formulations.

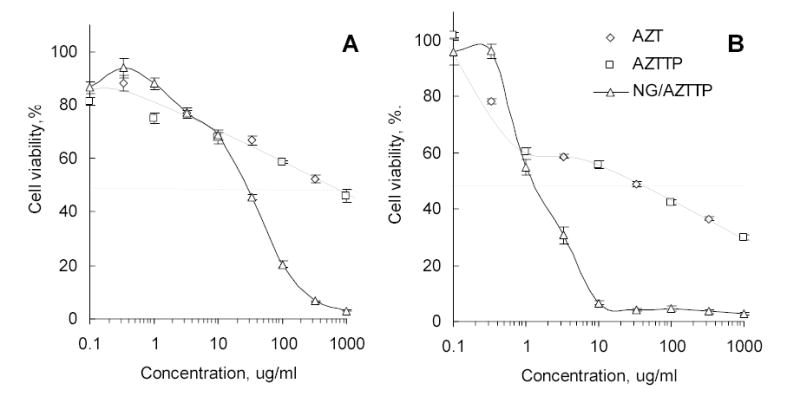

The cytotoxic activities of AZT, AZTTP, AZTTP/nanogel formulations and unloaded nanogels have been compared in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines by cell viability assay using MTT dye. Cells were treated with drugs/formulations for 24h and dose-response curves were obtained (Figure 6). The IC50 values were calculated by fitting the experimental data to a sigmoid curve (Table 3). Nanogel NG(PEG) showed a moderate cellular toxicity in MCF-7 (IC50 = 0.08 mg mL−1), but its formulation with AZTTP was significantly more cytotoxic (IC50 = 0.02 mg mL−1). This corresponds to an encapsulated AZTTP concentration of 9 μM. Both AZT and AZTTP have the same IC50 = 0.55 mg, which is equal to 2.1 and 1 mM, respectively. Therefore, drug cytotoxicity using nanogel formulations was increased > 200 times. Similar results were obtained in metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells. However, the cytotoxic effects of drugs and nanogels were significantly greater in this cell line, and IC50 values for AZT and AZTTP/nanogel formulation were 120 and 0.5 μM, respectively. This represents an increase in cytotoxicity of drug-nanogel formulations of 240 times. Control nanogel formulations containing ATP instead of AZTTP have demonstrated cytotoxicity up to 40 times lower compared to drug-loaded nanogels. The ATP-loaded nanogels were 3–5 times less toxic to cells than unloaded carriers following 24 h-treatment. In a separate experiment, we have observed an about 2-fold decrease in the cellular ATP level after 24 h-treatment with nanogels that could reflect an influence of the cationic carrier on energy production in MCF-7 cells. By contrast, the treatment of cells with ATP-loaded nanogels has no effect on the cellular ATP level (data not shown).

Figure 6.

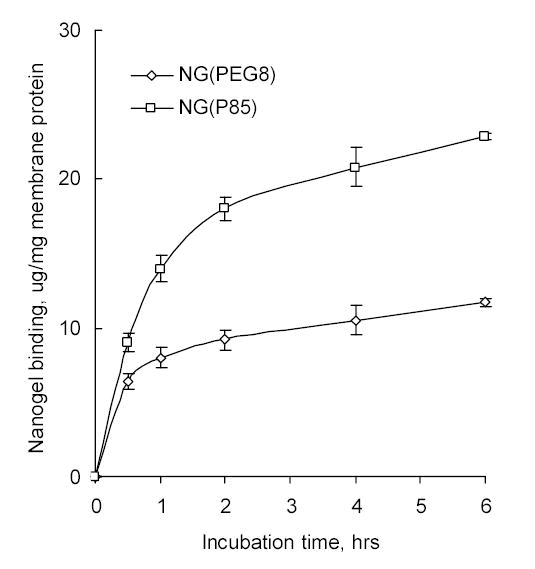

Binding of tritium-labeled Nanogels with isolated cellular (MCF-7) membranes. The quantity of membranes was the same in both experiments (equivalent to 1 mg of membrane protein).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of various drug (AZT) and nanogel formulations

| IC50 values (μM; mg/ml in italic) in the following cell lines* |

||

|---|---|---|

| Drug formulation | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 |

| AZT | 2,100 | 120 |

| AZTTP | 1,000 | 60 |

| Nanogel(PEG)/AZTTP | 9 / 0.02 | 0.5 / 0.0006 |

| Nanogel(PEG)/ATP | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| Nanogel (PEG) | 0.08 | 0.008 |

| Nanogel (P85) | 0.015 | 0.0025 |

Measured after 24h-incubation with the breast carcinoma cell lines.

Association of Nanogels with Cellular Membranes.

It is well-known that polycationic compounds can interact with negatively charged cellular membranes. Tritium-labeled nanogels have efficiently associated with isolated MCF-7 cellular membranes displaying standard saturation kinetics (Figure 7). Furthermore, NG(P85) nanogels made of more hydrophobic polymers showed a higher level of binding with cellular membranes, and the level of association of NG(P85) with membranes was two-fold compared to NG(PEG) after 2 h of incubation.

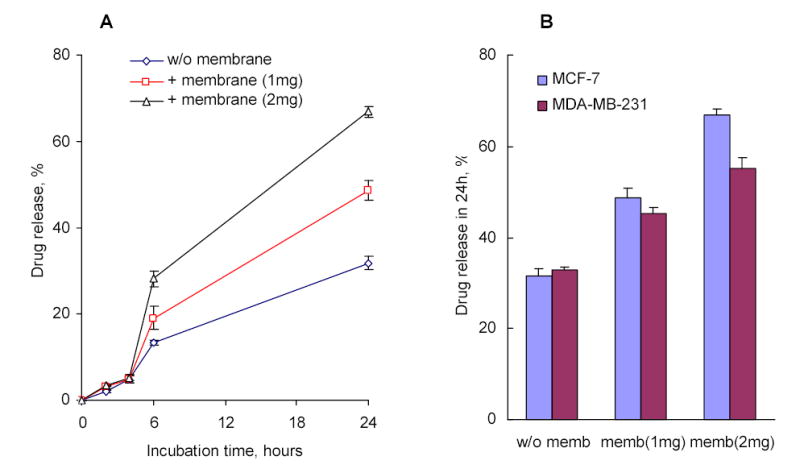

Figure 7.

In vitro drug release from AZTTP/Nanogel formulations in the presence of MCF-7 cellular membranes (1 or 2 mg of the membrane protein) (A); and a comparison of the release between MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cellular membranes following 24 h-incubation (B).

The interaction of nanogels with cellular membranes may play a role in drug release from these carriers. Evidently, there are several ways for drugs to be released in the cytosol. The first is from acidification inside endosomes resulting in the reduction of the total negative charge of NTPs and dissociation of the drug from the nanogel complex. The drug can then diffuse into the cytosol or be deposited there as a result of endosomal burst, which has been previously described as the “proton sponge effect” for PEI-based carriers 33. The second mechanism for drug release into the cytosol includes an interaction of nanogels with endogenic negatively charged proteins or polymers, which can occur in the blood circulation, or on the surface of cellular membranes. The third putative mechanism of drug release is caused by direct interaction or fusion of the nanogels with the cellular membrane.

We needed to confirm that the interaction of drug-loaded nanogels with the cellular membrane can trigger an efficient drug release from the carrier. To observe the in vitro drug release from AZTTP/nanogel formulations, we used a dialysis technique. The change in drug concentration versus time was measured spectrophotometrically inside semi-permeable dialysis bags, which allowed free drug to pass into the surrounding buffer and held the drug-encapsulated nanogels inside the bags. The drug release curve showed a cumulative 33% drug release after 24 h of incubation (Figure 7A). In parallel experiments, different quantities of isolated cellular membranes were added into a dispersion of drug-loaded nanogels, which resulted in about 2-fold increase of drug release during 24 h. This experiment shows two important implications of the nanogel-membrane interactions. The first is that drug release was accelerated by interaction of nanogels with membranes. And, the second is that the whole membrane-triggered process of drug release was very fast (around 6 h) and effective; almost the same drug release kinetics was observed after 6 h-incubation compared to the drug-nanogel formulation alone. The quantity of released drug was increased in this experiment at higher membrane to nanogels ratio. Cellular membranes isolated from different sources demonstrated also a different ability to bind nanogels. For example, membranes derived from MDA-MB-231 cells were slightly less effective than membranes from MCF-7 cells in promoting drug release from nanogels in the in vitro experiments (Figure 7B).

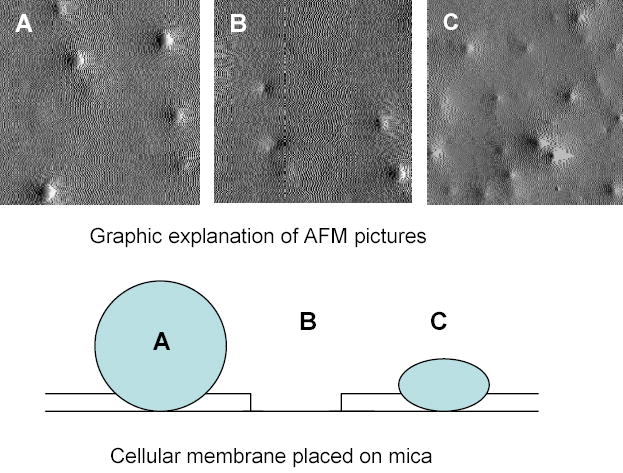

To obtain insight into the nanoscale interaction of nanogels with cellular membrane, atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies were performed using isolated cellular membranes placed on negatively charged mica. Suspensions of ATP-loaded nanogels NG(PEG) or NG(P85) were incubated with membranes for 2 hours. AFM pictures were obtained that clearly showed association of nanogel particles with membranes (Figure 9). NG(PEG) interacted with membrane, and particles with diameter ca. 50 nm were observed on the surface (Figure 8A). At select membrane regions, holes could be observed after incubation with NG(PEG) (Figure 8B), but not after incubation with NG(P85) (Figure 8C). The latter type can interact more efficiently with membranes as shown by a higher particle density on the membrane surface. The efficient binding of more hydrophobic nanogels makes them anchored or fused into the membrane. Thus, no holes were detected on AFM pictures of NG(P85) nanogels. By contrast, hydrophilic nanogels, NG(PEG) nanogels, may sporadically detach from the membrane, sometimes dislodging part of the associated membrane and producing holes in the phospholipid bilayer.

Figure 9.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of MCF-7 cells treated for 2 h with ATP-loaded Nanogels (bold black dots). Nanogels mostly accumulated inside of the endosomes, and were frequently associated with the membrane of the vesicles (A, B), some intracellular organelles, or outer cellular membranes (C, the two-cell contact area is shown).

Figure 8.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) of Nanogel particles incubated for 2 h with isolated cellular (MCF-7) membranes. Associated with the membrane NG(PEG) (A, B) or NG(P85) (C) were placed on negatively charged mica. Picture size is 2 x 2 microns.

Cellular Trafficking of Drug-Loaded Nanogels.

The interaction with cellular membranes and intracellular distribution of heavy metal-labeled nanogel particles have been investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Nanogel particles were labeled as a result of the spontaneous formation of PEI-copper(II) coordination complexes after mixing solutions of nanogels and Cu(NO3)2 34. Drug-loaded and copper-labeled nanogels appeared as small black particles and were easily visible under TEM (Figure 10). Nanogels avidly interact with intracellular membranes of endosomal vesicles (Figure 9A–B). The second picture clearly shows disrupted endosomes with nanogel particles remaining associated with its membrane (Figure 9B). Another site of abundant accumulation of nanogels was the outer cellular membrane, such as the area of contact between two MCF-7 cells illustrated in Figure 9C. A significantly lower level of accumulation in nuclear membranes was observed in these experiments. The membrane interactions of more hydrophobic NG(P85) nanogels showed a distinct pattern (Figure 9D). These particles appeared flattened and completely fused into the endosomal membrane. The distinctive membranotropic features of nanogel carriers are clearly visible in these pictures.

Figure 10.

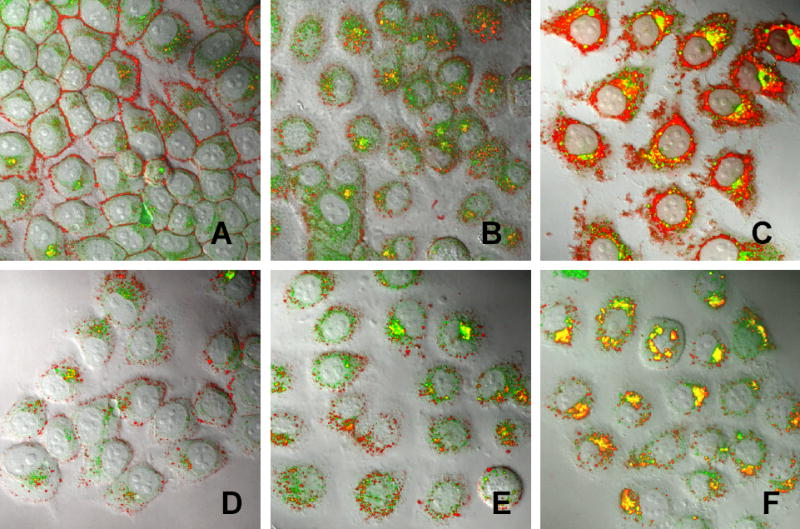

Cellular trafficking of drug-loaded Nanogels analyzed by confocal microscopy in MCF-7 cells after 30 min-incubation (A, D), 60 min-incubation (B, E) and 120 min-incubation (C, F) with NG(PEG) (A-C) or NG(P85)(D-E) at concentrations 0.01mg/ml of NG(PEG) or 0.005 mg/ml of NG(P85). Rhodamine-labeled Nanogels (red) contained encapsulated BODIPY FL ATP (green). Pictures are superimposed bright field and fluorescent images at magnification x 100.

Confocal microscopy was used to study the intracellular trafficking of fluorescently labeled nanogels and nanogel-encapsulated BODIPY-FL ATP. Rhodamine-labeled nanogels showed a rapid association with outer membranes of MCF-7 cells (30 min of incubation) (Figure 10A). However, after a 2 h-incubation most of the nanogel preparation was accumulated in endosomal vesicles across the cytosol and in the perinuclear region (Figure 10B). Release of green fluorescent BODIPY-FL ATP was clearly observed after a 4h-incubation; however, it was not clear whether the drug was released into cytosol or remained inside of endosomes (Figure 10C). Yellow areas show a superposition of red and green fluorescence. Part of it may be associated with drug-nanogel complexes, and another part may be produced separately by nanogels and drug sequestered inside endosomes. Similar pictures were obtained for drug-loaded NG(P85) nanogels. After 30 min of incubation, NG(P85) nanogels were mainly associated with outer membrane, and a significant quantity of drug was already observed in cytosol (Figure 10D). Obviously, the drug release followed an initial association with cellular membrane. After a 2h-incubation, a significant amount of nanogels was detected inside the cells as well as a higher level of drug trafficking into cytosol (Figure 10E). A longer incubation revealed that the drug-nanogel complex (yellow areas) preferred intracellular accumulation sites in the perinuclear region (Figure 10F). Drug-loaded NG(P85) nanogels demonstrated a similar drug release pattern compared to the NG(PEG). As discussed earlier, these two similar nanogel formulations may form complexes with phospholipids 21. This complex formation leads to substitution of the initial polyionic complexes (drug-nanogel formulations) and release of the less tightly associated nucleoside 5′-triphosphates. These new complexes have significant additional energy input and stabilization from hydrophobic interactions between phospholipids bound inside the nanogel network 35. This process is schematically illustrated in Figure 12. A significant amount of the released drug may cross the cellular membrane and enter the cytosol by this mechanism. In this case, nanogels remain fused with membrane and do not inflict any endosomal leakages. Efficient fusion with membranes and even formation of holes were recently documented for smaller cationic particles, high-generation dendrimers36. At the present time, we have not determined the actual impact of this process on drug release from nanogels. It is possible that there are other pathways active, as was discussed above. Nevertheless, this property of nanogels seems to be very promising, since it includes a mechanism of drug release triggered by interaction with cellular membranes. For example, a specific nanogel interaction with cellular membranes could be initially obtained as a result of receptor-mediated binding of vectorized nanogel carriers with targeted cancer cells.

Discussion

Our data showed that nanogels can be used as a drug delivery system for NTP analogs to substantially enhance the cytotoxicity of the corresponding drugs in cancer cells. Most NTP analogs act as chain growth terminators during nucleic acid synthesis. Therefore, the actual activity of these compounds is determined mainly by their fidelity for DNA polymerases rather than efficacy of cellular phosphorylation of related nucleoside analogs. Efficient termination of DNA synthesis by NTP analogs results in the arrest of cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Nanogel formulations of NTP analogs have circumvented problems previously associated with cytotoxic nucleoside analogs for chemotherapy—intracellular transport, enzymatic activation, and tissue specificity—by directly delivering NTP analogs into cancer cells. Additionally, as discussed in this paper, nanogel carriers have other pharmacological advantages as drug carriers.

Positively charged polymeric networks of dispersed nanogels are capable of loading the dissolved NTP analogs in the form of polyionic complexes rapidly condensed into nanosized particles. This approach is very mild, efficient, and non-damaging to the NTP structure compared to encapsulation into biodegradable nanoparticles or liposomes, for example. Drug-loaded nanogel formulations are easily dispersed in water, aggregationally stable, and (of importance from the pharmaceutical viewpoint) can be lyophilized; redissolved lyophilized formulations maintain the same particle size and can be injected intravenously. Particle size of drug-loaded nanogels around or less than 150 nm. This size is convenient in many aspects, for example: (i) it allows for sterilization of drug-nanogel formulations by filtration, (ii) particles can penetrate even small blood capillaries, and (iii) readily enter cells by endocytosis. The low buoyant density of nanogels makes them a unique type of drug carrier with a great potential for systemic administration.

In order to justify the application of more expensive phosphorylated drugs, we have proposed here a simple one-pot approach to the synthesis of NTP analogs using a mild phosphorylating reagent, tris-imidazolylphosphate 25,26. Nucleoside analogs lacking 3′ and 2′-hydroxyl groups can be easily converted into their 5′-triphosphates without chemical derivatization. As an example, AZT 5′-triphosphate (AZTTP) was obtained by this method with a high yield and purity. This nucleoside analog was previously shown to possess chemotherapeutic activity against breast cancer 37. Further searches for inexpensive nucleoside analogs that could be used as universal antimetabolites in the form of NTP analogs may lead to discovery of novel inexpensive drugs for cancer chemotherapy 38. Formulations of AZTTP with nanogels were found to have a significantly increased cytotoxicity compared to both the parent drug AZT and uncomplexed AZTTP and provide several other important benefits, such as an efficient cellular uptake and the possibility of a vectorized drug delivery. We have observed different sensitivity of two human breast carcinoma cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, to AZT, AZTTP and AZTTP-loaded nanogels. MCF-7 cells are estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), while metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells are known as estrogen receptor-negative (ER-). It has been proposed that sensitivity to chemotherapy by nucleoside analogs depends on ER expression in breast cancer cells 39. Actually, the difference observed here between the therapeutic sensitivity of these two types of breast cancer cells may make the application of drug-nanogel formulations especially useful for treatment of aggressive and metastatic types of cancer.

Drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles are usually taken into the cells by endocytosis and intracellular biodegradation of nanoparticles is a major factor of drug release. During this process, encapsulated NTP analogs will be rapidly degraded and inactivated inside the cell. Until now, only PEI and PEI-based carriers were able to induce endosomal escape of the encapsulated compounds 40. However, nanogel has an advantage over PEI because of its significantly lower cytoxicity. Nanogels usually become degraded after incubation for several days in aqueous solution; their degradation products, PEG-g-PEI block copolymers, are practically nontoxic and rapidly cleared from the body 19.

The most significant finding of this study was that drug release can be increased to a significant extent due to the interaction of nanogels with cellular membranes. Membranotropic properties of nanogels were confirmed in vitro and have been clearly demonstrated by various microscopic methods. Following interactions with membranes, drug-loaded nanogels actively release the formulated drug. Utilization of vectorized nanogels can further increase association of drug-loaded carriers with the cellular membrane through ligand-receptor binding. We have suggested here a mechanism of the membrane-mediated drug release. However, other mechanisms of nanogel escape from endosomes can contribute to the release of phosphorylated nucleoside analogs, such as formation of holes in the cellular membrane or even bursting of endosomes. At present, we cannot specify the general importance of the suggested mechanism, but it looks promising for the development of drug carriers capable of membrane-mediated release of encapsulated drugs.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the polyionic complex between protonated amino groups of branched PEI in Nanogels and phosphate groups of NTP analogs.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of AZT, AZTTP, and AZTTP/Nanogel formulations following the 24h-treatment as determined in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 (A) and MDA-MB-231 (B) cells using the MTT viability assay.

Figure 11.

Graphic representation of the Nanogel fusion with cellular membrane and substitution of the loaded drug (AZTTP) with anionic components of the phospholipid bilayer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute, grant R01 CA102791 (for SVV). We are extremely grateful to Luda Schlyakhtenko for AFM pictures, Tom Bargar for TEM images, and Janice Taylor for excellent assistance with confocal microscopy. Authors thank Dr. William Chaney for helpful discussion and Michael Jacobsen for help in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hatse S, De Clercq E, Balzarini J. Role of antimetabolites of purine and pyrimidine nucleotide metabolism in tumor cell differentiation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:539–555. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galmarini CM, Mackey JR, Dumontet C. Nucleoside analogues and nucleobases in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krayevsky A, Arzumanov A, Shirokova E, Dyatkina N, Victorova L, Jasko M, Alexandrova L. dNTP modified at triphosphate residues: substrate properties towards DNA polymerases and stability in human serum. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1998;17:681–693. doi: 10.1080/07328319808005209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kukhanova M, Krayevsky A, Prusoff W, Cheng YC. Design of anti-HIV compounds: from nucleoside to nucleoside 5′-triphosphate analogs. Problems and perspectives. Curr Pharm Des. 2000;6:585–598. doi: 10.2174/1381612003400687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner CR, Iyer VV, McIntee EJ. Pronucleotides: toward the in vivo delivery of antiviral and anticancer nucleotides. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:417–451. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200011)20:6<417::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RJ, Bischofberger N. Minireview: nucleotide prodrugs. Antiviral Res. 1995;27:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00011-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwendener RA, Schott H. Lipophilic 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl cytosine derivatives in liposomal formulations for oral and parenteral antileukemic therapy in the murine L1210 leukemia model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122:723–726. doi: 10.1007/BF01209119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JX, Sun X, Zhang ZR. Enhanced brain targeting by synthesis of 3′,5′-dioctanoyl-5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine and incorporation into solid lipid nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;54:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erion MD, van Poelje PD, Mackenna DA, Colby TJ, Montag AC, et al. Liver-targeted drug delivery using HepDirect prodrugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:554–560. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnani M, Rossi L, Fraternale A, Silvotti L, Quintavalla F, Piedimonte G, Matteucci D, Baldinotti F, Bendinelli M. Feline immunodeficiency virus infection of macrophages: in vitro and in vivo inhibition by dideoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate-loaded erythrocytes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:1179–1186. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraternale A, Rossi L, Magnani M. Encapsulation, metabolism and release of 2-fluoro-ara-AMP from human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1291:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(96)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnani M, Rossi L, Fraternale A, Casabianca A, Brandi G, Benatti U, De Flora A. Targeting antiviral nucleotide analogues to macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:133–137. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, Behr JP. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kichler A, Leborgne C, Coeytaux E, Danos O. Polyethylenimine-mediated gene delivery: a mechanistic study. J Gene Med. 2001;3:135–144. doi: 10.1002/jgm.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erbacher P, Bettinger T, Brion E, Coll JL, Plank C, Behr JP, Remy JS. Genuine DNA/polyethylenimine (PEI) complexes improve transfection properties and cell survival. J Drug Target. 2004;12:223–236. doi: 10.1080/10611860410001723487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Self-assembly of polyamine-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers with phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9:805–812. doi: 10.1021/bc980048q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinogradov S, Batrakova E, Li S, Kabanov A. Polyion complex micelles with protein-modified corona for receptor-mediated delivery of oligonucleotides into cells. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:851–860. doi: 10.1021/bc990037c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen HK, Lemieux P, Vinogradov SV, Gebhart CL, Guerin N, Paradis G, Bronich TK, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV. Evaluation of polyether-polyethyleneimine graft copolymers as gene transfer agents. Gene Ther. 2000;7:126–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradov SV, Batrakova EV, Li S, Kabanov AV. Mixed polymer micelles of amphiphilic and cationic copolymers for delivery of antisense oligonucleotides. J Drug Target. 2004;12:517–526. doi: 10.1080/10611860400011927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Nanosized cationic hydrogels for drug delivery: preparation, properties and interactions with cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinogradov SV, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Nanogels for oligonucleotide delivery to the brain. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:50–60. doi: 10.1021/bc034164r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinogradov SK, Kabanov AV. Synthesis of Nanogel carriers for delivery of active phosphorylated nucleoside analogues. Polymer Preprints. 2004;45:378–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinogradov S. Batrakova, E; Kabanov, A Poly(ethylene glycol)-polyethylenimine NanoGel particles: novel drug delivery systems for antisense oligonucleotides. Coll Surf B: Biointerf. 1999;16:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sergeeva NF, Solovieva VD, Shabarova ZA, Prokof’ev MA, Zarytova VF, Lebedev AV, Knorre DG. Reaction of deoxyribonucleosides and dinucleoside phosphates with phosphoryl chloroimidazolides and phosphoryl triimidazolide in pyridine solution. Bioorg Khim. 1976;2:1056–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinogradov SV, Berlin YuA. Modified nucleosides: oligonucleotides, containing 5-trimethylsilyl-2′-deoxyuridine residue. Nucl Acid Res Symp Ser. 1984;14:271–272. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decosterd LA, Cottin E, Chen X, Lejeune F, Mirimanoff RO, Biollaz J, Coucke PA. Simultaneous determination of deoxyribonucleoside in the presence of ribonucleoside triphosphates in human carcinoma cells by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:59–68. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamada H, Tsuruo T. Characterization of the ATPase activity of the Mr 170,000 to 180,000 membrane glycoprotein (P-glycoprotein) associated with multidrug resistance in K562/ADM cells. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4926–4932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panyam J, Sahoo SK, Prabha S, Bargar T, Labhasetwar V. Fluorescence and electron microscopy probes for cellular and tissue uptake of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2003;262:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer B, Boyer JL, Hoyle CH, Ziganshin AU, Brizzolara AL, Knight GE, Zimmet J, Burnstock G, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Identification of potent, selective P2Y-purinoceptor agonists: structure-activity relationships for 2-thioether derivatives of adenosine 5′-triphosphate. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3937–3946. doi: 10.1021/jm00076a023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoard DE, Ott DG. Conversion Of Mono- And Oligodeoxyribonucleotides To 5-Triphosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:1785–1788. doi: 10.1021/ja01086a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang SJ, Davis ME. Cationic polymers for gene delivery: designs for overcoming barriers to systemic administration. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2001;3:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ungaro F, De Rosa G, Miro A, Quaglia F. Spectrophotometric determination of polyethylenimine in the presence of an oligonucleotide for the characterization of controlled release formulations. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2003;31:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(02)00571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronich TV, Vinogradov SV, Kabanov AV. Interaction of nanosized copolymer networks with oppositely charged amphiphilic molecules. NanoLett. 2001;1:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang ZY, Smith BD. High-generation polycationic dendrimers are unusually effective at disrupting anionic vesicles: membrane bending model. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:805–814. doi: 10.1021/bc000018z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner CR, Ballato G, Akanni AO, McIntee EJ, Larson RS, Chang S, Abul-Hajj YJ. Potent growth inhibitory activity of zidovudine on cultured human breast cancer cells and rat mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2341–2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGuigan C, Kinchington D, Wang MF, Nicholls SR, Nickson C, Galpin S, Jeffries DJ, O’Connor TJ. Nucleoside analogues previously found to be inactive against HIV may be activated by simple chemical phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1993;322:249–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81580-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mobley JA, Brueggemeier RW. Increasing the DNA damage threshold in breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;180:219–226. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kircheis R, Wightman L, Wagner E. Design and gene delivery activity of modified polyethylenimines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:341–358. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]