Abstract

The circadian clock of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 imposes a global rhythm of transcription on promoters throughout the genome. Inactivation of any of the four known group 2 sigma factor genes (rpoD2, rpoD3, rpoD4, and sigC), singly or pairwise, altered circadian expression from the psbAI promoter, changing amplitude, phase angle, waveform, or period. However, only the rpoD2 mutation and the rpoD3 rpoD4 and rpoD2 rpoD3 double mutations affected expression from the kaiB promoter. A striking differential effect was a 2-h lengthening of the circadian period of expression from the promoter of psbAI, but not of those of kaiB or purF, when sigC was inactivated. The data show that separate timing circuits with different periods can coexist in a cell. Overexpression of rpoD2, rpoD3, rpoD4, or sigC also changed the period or abolished the rhythmicity of PpsbAI expression, consistent with a model in which sigma factors work as a consortium to convey circadian information to downstream genes.

Cyanobacteria are the simplest organisms known to exhibit circadian rhythms of biological activities, including gene expression (13). These are endogenously generated oscillations that have a period of ∼24 h under constant conditions and are robustly maintained in the absence of external timing cues (26). In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, some components of the circadian clock have been identified by genetic analysis, with luciferase gene fusions as phenotypic reporters of circadian gene expression (10, 12, 15, 19, 29, 32). Genetic complementation of mutants with circadian periods between 14 and 60 h and of arrhythmic mutants with distorted waveforms (17) identified three novel genes, kaiA, kaiB, and kaiC (10). Disruption of any individual kai gene abolishes circadian rhythms, suggesting that these genes are central to the timing mechanism (10). Although putative kai orthologs exist in other groups of prokaryotes, the deduced amino acid sequences of Kai proteins have little similarity with proteins of known function from other organisms (10).

The specific functions of the Kai proteins are still cryptic, but some of their biochemical properties are known. KaiB and KaiC protein levels cycle robustly under constant conditions, whereas KaiA abundance shows little oscillation (33). The three Kai proteins form homo- and heteromultimeric complexes, and the physical interactions among them seem to be important for generation of circadian rhythms (11, 34). KaiC shows autophosphorylation and ATP-binding activities, which are also likely to be significant for circadian function (25).

In S. elongatus, the circadian clock globally regulates expression of the entire genome, although many promoters are expressed with a specific waveform or relative phasing that indicates specialization of circadian expression (20). Even an artificial Escherichia coli consensus promoter, PconII (6), drives rhythmic expression of the luciferase (luxAB) genes in the cyanobacterium (32). This is contrary to observations from well-characterized eukaryotic circadian model organisms in which only a small percentage of genes are known to be under circadian control and specific cis elements confer rhythmicity (2, 8, 35). How temporal information is transduced from the central Kai oscillator globally to the ∼3,000 genes in the S. elongatus genome is not known. Circadian control is so extensive in S. elongatus that it is almost inconceivable that each set of genes has its own dedicated transcription factor(s) responsible for its circadian expression. Instead, we propose that regulatory mechanisms that are more global are responsible for transducing temporal information to all downstream genes.

Previous work implicated the basic transcription machinery in circadian control. Inactivation of rpoD2, an S. elongatus group 2 sigma factor gene, results in circadian rhythms with low amplitude, albeit high expression levels, from a subset of reporter genes including psbAI (32). This observation placed rpoD2 as a component of an output pathway from the circadian oscillator that affects transmission of temporal information to some genes (32). Group 2 comprises sigma factors that are sigma 70-like in sequence but not essential for growth (23). Cyanobacteria are unusual in having several closely related group 2 sigma factors in addition to the essential, principal sigma, RpoD1 (30). Genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that the holoenzyme comprising different group 2 sigma factors can recognize S. elongatus promoters (7, 24).

Two models were proposed to explain the limited effect of rpoD2 inactivation on the amplitude of oscillation from some genes. In one, RpoD2 is necessary for transcribing a gene that encodes a factor responsible for generating the circadian trough (e.g., a time-dependent repressor of psbAI expression). In another, the loss of RpoD2 allows access of other sigma factors to the psbAI promoter by relieving competition.

In order to distinguish between these possibilities, we disrupted other known group 2 sigma factor genes, rpoD3, rpoD4, and sigC, to see whether their loss would cause a circadian defect as predicted by a sigma competition model. We found that removing any one of the four group 2 sigma factors of S. elongatus affects circadian properties of a subset of reporter genes, suggesting that the combinatorial action of sigma factors contributes to wild-type circadian rhythmicity. All pairwise inactivations of these sigma factor genes also affected the circadian properties of the psbAI reporter, but only two combinations had a notable effect on the expression of PkaiB and PpurF. Taken together, the data indicate that these sigma factors, although structurally similar and partially overlapping in function, are not entirely redundant. Circadian alterations accompanied overexpression of each of four group 2 sigma factors, consistent with a model in which rhythmicity of gene expression derives from temporal modulation of the holoenzyme pool. Disruption of one sigma factor gene, sigC, showed a lengthening of the period of expression from the psbAI promoter by about 2 h but did not affect that from the kaiB and purF promoters to the same extent. These data indicate that it is possible for two or more oscillations of different periodicities to coexist in S. elongatus. Immunoblot analysis revealed oscillation of RpoD4 in protein levels during the circadian cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inactivation of sigma factor genes.

Inactivation of each of the four sigma factor genes has been described previously for a PpsbAI reporter strain (24). Single or pairwise inactivations were made in the reporter strains AMC393 (−185 to +224 of PpsbAI fused to the luxAB reporter integrated in neutral site II [NS2] and psbAI::luxCDE in neutral site I [NS1]; Gmr cassette in sigC), AMC669 (−185 to +224 of PpsbAI::luxAB and PpsbAI::luxCDE integrated in NS2; Kmr cassette in rpoD2, rpoD3, or rpoD4), AMC777 (−54 to +43 of PpsbAI fused to luxAB integrated in NS2 and PpsbAI::luxCDE in NS1; used for pairwise sigma factor inactivation effect on PpsbAI), AMC462 (PkaiB::luxAB in NS2 and PpsbAI::luxCDE in NS1), and AMC408 (PpurF::luxAB in NS2 and PpsbAI::luxCDE in NS1). Transformants were selected on BG-11 M agar with kanamycin (20 μg/ml) and/or gentamicin (2 μg/ml), as appropriate.

Bioluminescence assays.

All strains were derived from S. elongatus PCC 7942 and carry, in addition to the luxAB gene set, a PpsbAI::luxCDE construct that directs synthesis of the long-chain aldehyde substrate for luciferase in vivo, making the reporter strains autonomously bioluminescent. Cultures grown on BG-11 M agar (3) were inoculated onto BG-11 M agar in 96-well microtiter plates. Appropriate antibiotics were included in the agar. The microtiter plates with samples were incubated in constant light (LL) conditions for 6 h and then subjected to a 12-h entraining dark incubation to synchronize the clocks of all cells in the population (15). Bioluminescence rhythms were assayed from luciferase reporter strains in at least two independent experiments on a Packard TopCount luminometer (1, 15). Because light intensity has a minor effect on circadian period (less than 1 h) and because absolute expression levels (but not circadian parameters) vary with cell number, all mutant and control analyses reported here were calculated from samples carefully paired on the monitoring device for equivalent illumination from samples grown in parallel under identical conditions. Note that some cycle-to-cycle variations in amplitude and expression levels are normal. Data were imported into Microsoft Excel 2000 for plotting. Phase, amplitude, and period were calculated by using the Fourier analysis software, FFT-NLLS, version 98.5, from the Import & Analysis software package (M. Straume, National Science Foundation [NSF] Center for Biological Timing, University of Virginia).

Overexpression of sigma factor genes.

Each sigma factor gene was amplified from S. elongatus PCC 7942 chromosomal DNA by PCR with Pwo polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and primers that incorporated restriction enzyme sites for cloning into the cyanobacterial overexpression vector p322Ptrc (19). Each sigma factor coding region was cloned directly in frame with the ATG of the vector at the NcoI site. Primer pairs and resulting restriction sites for each gene were as follows: rpoD2, 5′-CTCTCTCATGAGTACCTCCTCCGC-3′ (BspHI; compatible with NcoI site in the vector) and 5′-TCTCGGATCCAACCTAGCTAGCTGCG-3′ (BamHI); rpoD3, 5′-TCATGCCATGGCCAAAACTGAAACCCC-3′ (NcoI) and 5′-TCTCGGATCCACACTAGCTAGCCAAG-3′ (BamHI); rpoD4, 5′-CTCTCTCACTCTCTCATGAACGTACAGGAACGC-3′ (BspHI) and 5′-CGATCGAGCTCAGCCTAGCAAGCCTCTGG-3′ (SacI); sigC, 5′-CTCTCTCATGACGGCTGCC-3′ (BspHI) and 5′-CGATCGAGCTCCGACTAGTGCAACAACTCC-3′ (SacI).

Fusions of Ptrc to rpoD3, rpoD4, and sigC were then cloned as BglII fragments into the NS1 vector pAM1303 to incorporate the overexpression constructs into the cyanobacterial genome (18). A 4-kb BstZ171-NgoMIV fragment bearing the rpoD2 coding region fused to the Ptrc promoter was cloned into the NS1 vector pAM2314 cut with XmaI and StuI. The nucleotide sequence of each construct was confirmed by using the cycle sequencing method (dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction, ABI PRISM; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). AMC669 was transformed with each overexpression construct, and clones were selected on BG-11 M plates with spectinomycin (20 μg/ml). Bioluminescence from overexpression strains was monitored after inducing expression of the sigma factors by adding 2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and subjecting the cells to a 12-h dark pulse to synchronize the clock.

Complementation of the sigC, rpoD3, and rpoD4 mutations.

sigC, rpoD3, and rpoD4 were inactivated in AMC669, a PpsbAI::luxAB reporter strain. The resultant strains bearing rpoD3 and rpoD4 mutations were transformed with the rpoD3 and rpoD4 overexpression constructs, respectively, with the ectopic copies of the sigma factor genes in NS1 (4). Bioluminescence rhythms were measured in the absence of IPTG; the Ptrc promoter allows low-level constitutive expression of genes in S. elongatus. A 3.1-kb BamHI fragment from pAM2330, bearing the sigC gene, was cloned into pAM1303 to create pAM2337. This construct was used to transform a PpsbAI::luxAB strain in which sigC was disrupted.

Preparation of protein extracts and immunoblots to detect overexpression of RpoD3 and RpoD4.

Cultures (100 ml) of wild-type and overexpression strains of RpoD3 and RpoD4 were grown to an optical density of ∼0.7 at 750 nm in shaking flasks in CO2-enriched air (1%) at a light intensity of 150 microeinsteins m−2 s−1. The cultures were divided, and 2 mM IPTG was added to one half of each culture to induce the expression of the respective sigma factor. The flasks were incubated for an additional 12 h, then cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and resuspended in the same buffer to give a final volume of 2 ml. The cell suspension was passed twice through a prechilled French pressure cell at 137.9 MPa (20,000 lb/in2). Fifteen micrograms of the protein extract from the uninduced sample and 7.5 and 15 μg of protein from the induced sample were suspended in a β-mercaptoethanol-containing denaturing buffer system, boiled for 5 min, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (BA85S; Schleicher and Schuell) as previously described (22). Proteins were immunostained with anti-RpoD3 and anti-RpoD4 antisera at a dilution of 1:15,000 and detected by the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). Antisera raised against RpoD2, RpoD3, and RpoD4, expressed in E. coli, were provided by Kan Tanaka, University of Tokyo. To determine the degree to which each cross-reacts with other sigma factors, we compared immunostains of extracts prepared from wild-type and specific rpoD-inactivated and rpoD-overexpressing S. elongatus strains. The results indicated that the anti-RpoD4 serum recognizes itself and overexpressed RpoD3; however, the amount of RpoD3 in wild-type cells was too low to be detected by anti-RpoD3 antiserum. We concluded that anti-RpoD4 primarily recognizes RpoD4 in wild-type cells.

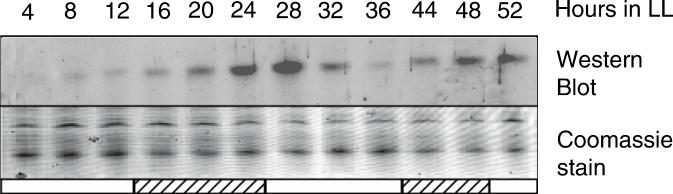

Immunoblots to detect cycling of RpoD4.

Cells were grown in culture tubes suspended in a 30°C water-filled aquarium under aeration (1% CO2) in LL conditions of 200 microeinsteins m−2 s−1 (28). Cultures were exposed to two light-dark pulses of 12 h each to synchronize the circadian clock and then returned to LL conditions. Samples corresponding to 2 ml at an optical density at 750 nm of 0.55 were collected at 4-h intervals and frozen at −20°C. Samples were resuspended in a β-mercaptoethanol-containing denaturing buffer and boiled for 5 min in a water bath. Ten microliters of the protein sample was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis as described above. The anti-RpoD4 antiserum was used at a dilution of 1:15,000. Posttransfer gels were stained with Coomassie blue to verify even loading of total protein.

Monitoring rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC gene expression as bioluminescence from a luciferase reporter.

A 1-kb SmaI-to-PstI fragment carrying the upstream region of rpoD3 recovered from pAM1309 was blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase and cloned into pAM1580 digested with StuI. The upstream region of sigC (1.2-kb EcoRV-SalI fragment) from pAM2330 was cloned into pAM1580 cut with SmaI and SalI. Strain AMC395, carrying psbAI-driven luxCDE genes to provide an aldehyde substrate for luciferase and a spectinomycin-streptomycin resistance marker in NS1, was transformed with the pAM1580 derivatives. The PrpoD2::luxAB fusion was reported previously (15). Bioluminescence from these strains was monitored as described above. No stable promoter fragment clone was obtained from the upstream region of rpoD4 (data not shown).

RESULTS

Differential effects of inactivating group 2 sigma factor genes on circadian expression of genes in different output pathways.

We inactivated each of the four group 2 sigma factor genes, rpoD2, rpoD3, rpoD4, and sigC, singly in a PpsbAI::luxAB reporter strain and monitored bioluminescence levels in LL after an entraining 12-h dark pulse. As reported earlier by screening with a cooled charge-coupled device camera and uniform sample illumination, the disruption of rpoD2 decreased the peak-to-trough amplitude of the circadian expression rhythm from PpsbAI::luxAB (32).

However, in our present screening device, the low-amplitude phenotype could not be assigned to loss of trough and was conditional, depending on light intensity reaching the sample, i.e., evident at 230 microeinsteins m−2 s−1 (Fig. 1A) but not at 50 microeinsteins m−2 s−1 (data not shown). An approximately 50% decrease in amplitude also resulted from the loss of rpoD3 (5.3 × 103 ± 0.8 × 103 versus 8.2 × 103 ± 0.5 × 103, n = 12) or rpoD4 (4.5 × 103 ± 1.9 × 102 versus 8.2 × 103 ± 0.5 × 103, n = 12). The phasing of the peaks was advanced by ∼4 h in both the rpoD3 and rpoD4 mutant backgrounds relative to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B and C, respectively). Inactivation of sigC caused a lengthening of the PpsbAI::luxAB expression rhythm by about 2 h (27.2 ± 0.4 h versus 25.1 ± 0.3 h, n = 20) and consistently increased overall bioluminescence and amplitude of the oscillation (Fig. 1D). Genetic complementation confirmed that the observed phenotypes resulted from the loss of the given sigma factor gene rather than from polar effects on adjacent loci (32) (also data not shown).

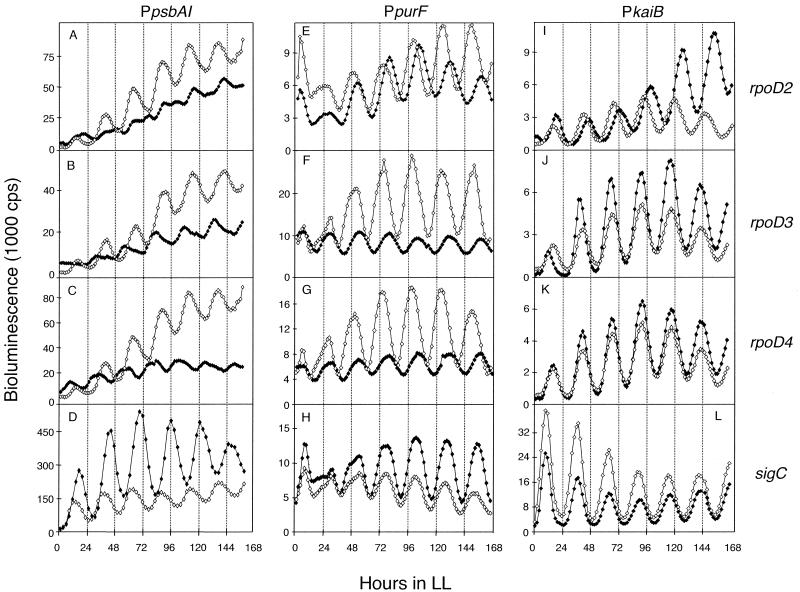

FIG. 1.

Circadian expression rhythms of PpsbAI::luxAB, PpurF::luxAB, and PkaiB::luxAB reporter strains in which the rpoD2, rpoD3, rpoD4, or sigC gene has been inactivated. Bioluminescence traces are shown from wild-type (open diamonds) and sigma-inactivated mutant (closed diamonds) strains that carry the reporter gene shown above each column of panels. The gene inactivated in each reporter strain is indicated at the end of each row. The x axis shows time in hours after the cells were released into LL. The y axis indicates bioluminescence (in units of 1,000 cps). Sigma factor gene inactivations are: rpoD2 (A, E, and I), rpoD3 (B, F, and J), rpoD4 (C, G, and K), and sigC (D, H, and L). Traces are representative of bioluminescence measured from at least three replicates of four independent transformants for each sigma factor mutant. Note that the wild-type psbAI::luxAB reporter strain used for inactivation of sigC in panel D is of a different genetic background than that used for inactivation of the other sigma factor genes in panels A, B, and C (see Materials and Methods). The overall expression level is higher for the AMC393 reporter than for AMC669, but the circadian properties of the strains are equivalent.

Thus, disruption of any of the group 2 sigma factors affected the circadian expression of the psbAI promoter. This is more consistent with a model in which RpoD2 depletion allows access to the psbAI promoter by an RNA polymerase associated with other sigma factors than with one based on RpoD2-dependent expression of a specific circadian regulatory factor. The sigma factor inactivations did not identically affect the psbAI promoter, indicating that the activities of the sigma factors are not entirely redundant.

We chose the PpurF::luxAB and PkaiB::luxAB reporter strains as representative of classes of promoters different from PpsbAI (15) to determine whether the loss of each of the group 2 sigma factors also affected their rhythmic expression. The circadian expression pattern of PpurF is nearly opposite that of PpsbAI, i.e., its expression peaks at subjective dawn (circadian times [CT] of 24 and 48 h, etc., where 1 CT h = 1/24 of one circadian cycle) (20). The kaiB promoter drives very high amplitude expression of kaiB and kaiC, which are central clock genes in S. elongatus (10). Mutations in other genes have been shown to affect the circadian expression of PpsbAI but not of PpurF or PkaiB, suggesting that these genes are in different output pathways (15, 32).

As shown in Fig. 1E, and as reported previously, disruption of rpoD2 had no effect on the amplitude of PpurF::luxAB expression (32). However, we observed an increase in period length by about 1 h (26.6 ± 0.5 h versus 24.8 ± 0.3 h, n = 20), which was not detected previously (32). The circadian oscillation of PkaiB::luxAB expression was also lengthened by about 1 h (26.4 ± 0.5 h versus 25.1 ± 0.3 h, n = 20), with no change in amplitude (Fig. 1I). The period lengthening is, by eye, also possible to detect for PpsbAI, but the low amplitude of that oscillation impaired calculation of the period value (Fig. 1A). We assume that this reflects a small fundamental change in the period of the central oscillator in the rpoD2 mutant.

Inactivation of other sigma factor genes affected additional circadian properties of PpurF. The disruption of rpoD3 or rpoD4 changed the phase angle (relative timing of the peaks), amplitude, and expression level of a PpurF::luxAB reporter strain (Fig. 1F and G). Either mutation consistently delayed the peaks of PpurF::luxAB bioluminescence by about 3 h and decreased the amplitude of expression to one half and the expression level itself to one third of those in the wild type. The same mutations had no significant effect on the bioluminescence rhythms of a PkaiB::luxAB reporter strain (Fig. 1J and K).

The sigC null mutant, which consistently lengthened the period of psbAI expression by 2 h (Fig. 1D), had little or no effect on the period of expression from the PpurF::luxAB (25.2 ± 0.2 h versus 24.8 ± 0.3 h, n = 12) and PkaiB::luxAB (24.9 ± 0.3 h versus 25.1 ± 0.1 h, n = 12) reporter strains (Fig. 1H and L, respectively). In some experiments, sigC inactivation increased PpurF::luxAB and PkaiB::luxAB periods ∼0.8 h over the periods of the respective wild-type reporter strains but never to the extent seen in the PpsbAI reporter. The loss of sigC extended the period of expression from PkaiA, PpsbAIII, and PconII similarly to that from PpsbAI (data not shown).

The individual inactivation of the four group 2 sigma factors dissimilarly affected the circadian expression patterns of different reporter genes, supporting the assignment of these genes to different output pathways from the circadian clock. However, none of the sigma factors was genuinely essential for expression of any of the tested genes or for circadian rhythmicity.

Pairwise inactivation of sigma factor genes affects a broader spectrum of gene expression rhythms.

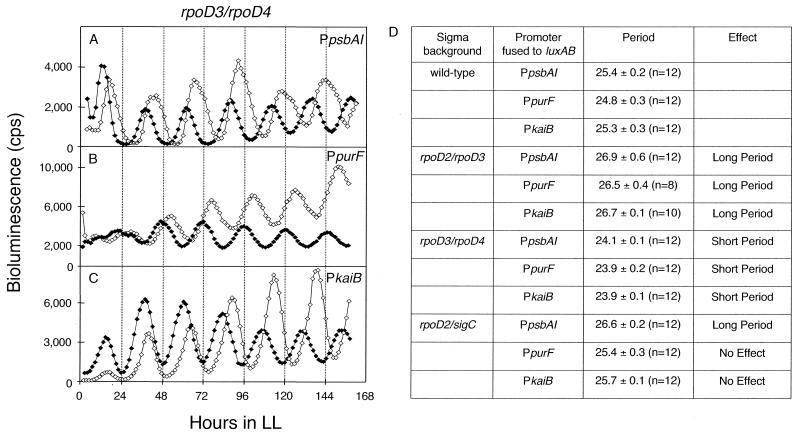

We assessed the effects of pairwise inactivation of group 2 sigma factors on the PpsbAI, PpurF, and PkaiB expression patterns in order to determine whether a larger subset of genes would be affected by their loss. All six combinations of sigma factor mutations affected the phase, amplitude, or expression from PpsbAI (Fig. 2D and data not shown). However, only two combinations had an effect on either PpurF or PkaiB. The rpoD2 rpoD3 double mutation lengthened, and the rpoD3 rpoD4 double mutation shortened, the circadian periods from all three reporter strains by ∼1.5 h (Fig. 2). The rpoD2 sigC double mutation led to a ∼1.5-h-long period of PpsbAI::luxAB expression but had no significant effect on the periods of expression of the PpurF::luxAB and PkaiB::luxAB reporters, confirming the ability of mutations to differentially affect the periods of different reporters (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Effects of pairwise inactivations of sigma factors on period lengths of PpsbAI, PpurF, and PkaiB expression rhythms. Effect of the rpoD3 rpoD4 double null mutation on PpsbAI::luxAB (A), PpurF::luxAB (B), and PkaiB::luxAB (C) bioluminescence rhythms. Open diamonds and closed diamonds represent wild-type and mutant traces, respectively. The x and y axes are labeled as described for Fig. 1 except that the units for bioluminescence are counts per second. Traces are representative of bioluminescence measured from at least three replicates of four independent transformants. (D) Effects of pairwise inactivations of rpoD2-rpoD3, rpoD3-rpoD4, and rpoD2-sigC on the periods of PpsbAI::luxAB, PpurF::luxAB, and PkaiB::luxAB expression rhythms.

The absence of effect on PkaiB when either rpoD3 or rpoD4 is missing (Fig. 1J and K), but mutant phenotype when both are lost (Fig. 2C and D), suggests that these sigma factors redundantly recognize PkaiB. We propose that this short period effect on PkaiB, which drives expression of the essential clock components KaiB and KaiC, cascades to the other promoters PpsbAI and PpurF via a change in the central oscillator period.

Effects of sigma factor overexpression on psbAI expression rhythms.

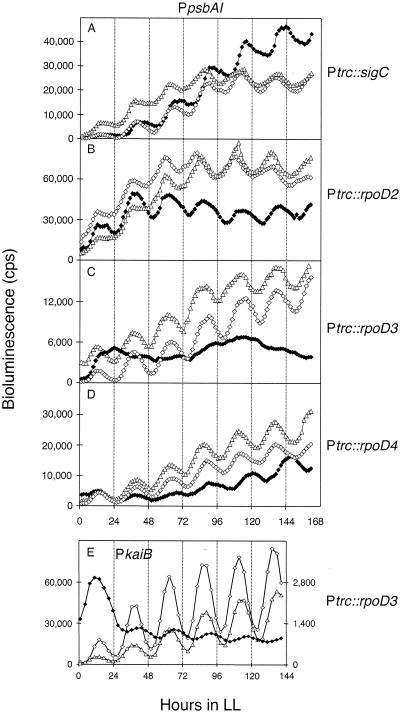

If sigma factors compete for association with the core RNA polymerase, and if different forms of holoenzyme can recognize S. elongatus promoters (7), we would predict that disrupting the normal pool by overabundance of any one sigma factor would result in abnormal rhythmicity of gene expression. We placed the coding region of each of the four group 2 sigma factor genes under transcriptional control of the IPTG-inducible trc promoter and assayed the effects of overexpression on PpsbAI::luxAB expression. As shown in Fig. 3A, B, and D, the period of PpsbAI expression rhythm increased by approximately 2 h with overexpression of SigC (26.8 ± 0.3 h versus 24.8 ± 0.3 h, n = 6), RpoD2 (26.7 ± 0.3 h versus 24.4 ± 0.3 h, n = 6), or RpoD4 (26.9 ± 0.4 h versus 24.8 ± 0.3 h, n = 6). Overexpression of RpoD3 resulted in arrhythmic expression of PpsbAI::luxAB (Fig. 3C). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that RpoD3 and RpoD4 (for which antisera were available) were overexpressed after administration of IPTG, reaching eight- and fourfold, respectively, over their corresponding uninduced levels (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Differential effects of sigma factor overexpression. The overexpression of sigC (A), rpoD2 (B), rpoD3 (C), or rpoD4 (D) on rhythms from a PpsbAI::luxAB and rpoD3 (E) on a PkaiB::luxAB reporter strain. Overexpression was induced in bioluminescent reporter strains by the addition of 2 mM IPTG immediately before the entraining 12-h dark pulse. Open triangles, bioluminescence rhythms from wild-type reporter strains; open and closed diamonds, rhythms from reporter strains bearing sigma factor overexpression constructs in the absence and presence, respectively, of the inducer. The gene overexpressed from the trc promoter is indicated at the end of each row. The x and y axes are the same as in Fig. 2. Traces are representative of bioluminescence measured from at least six independent samples for each sigma factor overexpression.

We wanted to determine whether arrhythmic expression of PpsbAI when RpoD3 is overexpressed represented a complete cessation of Kai clock function itself. Many mutations, including the sigma factor inactivations reported here, dramatically alter PpsbAI oscillation while leaving PkaiB expression unaffected. Therefore, we assayed a PkaiB::luxAB strain in which RpoD3 was overexpressed. IPTG induction reduced the magnitude of expression by a factor of 10 and decreased the amplitude of oscillation, but the expression was still notably rhythmic (Fig. 3E). Thus, overexpression of RpoD3 does not stop the clock altogether.

Expression patterns of rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC.

We constructed transcriptional fusions between promoterless luxAB and upstream regions of rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC to determine the relative phasing and expression patterns of the sigma factor genes themselves (15). Attempts to produce a similar reporter for rpoD4 produced only unstable clones, so expression of that gene could not be assayed.

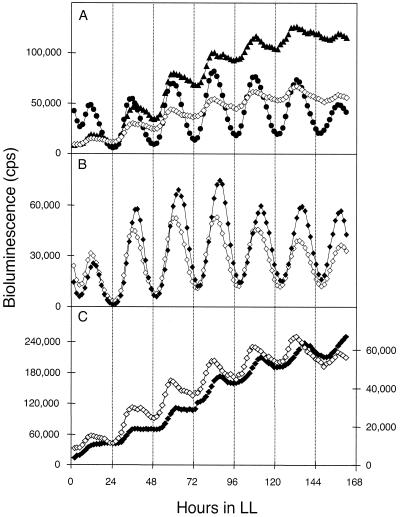

All three sigma factor promoters were strongly expressed with peaks of reporter activity at subjective dusk (class 1 phase) like most genes in S. elongatus (Fig. 4A). The amplitude of the PsigC::luxAB reporter is one order of magnitude higher than that of PrpoD2::luxAB or PrpoD3::luxAB. No difference in relative phasing of the rhythms was observed. However, the reporter cannot identify differences in transcription, mRNA stability, protein accumulation, or properties of proteins such as activity or ability to bind to the RNA polymerase core, any of which may vary over CT.

FIG. 4.

Expression patterns of rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC and the effect of the loss of sigC and rpoD2 on their respective oscillations. (A) The upstream regions of rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC were fused to luxAB, and the expression patterns of these sigma factor genes were monitored. Closed triangles, PrpoD3::luxAB; closed circles, PsigC::luxAB; open diamonds, PrpoD2::luxAB. (B) Inactivation of sigC in a PsigC::luxAB reporter strain. Open diamonds, wild-type PsigC::luxAB reporter strain; closed diamonds, sigC mutant PsigC::luxAB reporter strain. (C) Inactivation of rpoD2 in a PrpoD2::luxAB reporter strain. Open diamonds, wild-type PrpoD2::luxAB reporter strain, with y axis scale at right; closed diamonds, PrpoD2::luxAB rpoD2 mutant trace, with y axis scale at left. The x and y axes are the same as for Fig. 2. Traces are representative of bioluminescence measured from at least three replicates of four independent transformants.

To assess the effect of the loss of each sigma factor on its own gene's oscillation, we inactivated rpoD2, rpoD3, and sigC genes in their respective reporter fusion backgrounds. The inactivation of rpoD2 lead to an ∼4-fold-elevated expression from an rpoD2::luxAB fusion (Fig. 4C). The period of PrpoD2::luxAB expression was not affected by the loss of rpoD2, whereas PpurF::luxAB and PkaiB::luxAB rhythms were extended by ∼1 h (Fig. 1E and I). We concluded that rpoD2 negatively regulates its own expression, either directly or indirectly. The inactivation of rpoD3 (data not shown) and sigC (Fig. 4B) had no effect on their own oscillations. We propose that while rpoD3 and sigC are involved in the recognition of promoters like PpsbAI, their own promoters may be recognized solely by RNA polymerase complexed with the principal sigma factor RpoD1.

Cycling of RpoD4 protein under constant conditions.

Because the transcriptional luciferase reporter fusions do not report posttranscriptional events for the genes under study, we wanted to determine whether sigma factors themselves accumulate in a rhythmic manner. Although the promoter activities of all genes tested in S. elongatus are rhythmic when fused with the luciferase reporter, and mRNA abundances for psbAI, psbAII, purF, kaiA, and kaiBC oscillate in a circadian fashion, only the clock proteins KaiB and KaiC have been demonstrated to oscillate at the protein level under LL conditions (10, 12, 16, 33). An antiserum raised against RpoD4 (a gift from K. Tanaka, University of Tokyo) was sufficiently specific to track the abundance of that protein over a CT scale.

Immunoblot analysis showed that the RpoD4 protein level oscillates as a function of time, with peaks near 28 and 52 h in LL conditions (Fig. 5). The timing of these peaks is almost opposite to those of the bioluminescence patterns from rpoD2::luxAB, rpoD3::luxAB, and rpoD2::luxAB. However, we do not know whether this reflects a difference in the timing of expression of the rpoD4 and the other sigma factor genes or a difference between peaks of transcription and protein accumulation.

FIG. 5.

Rhythmic abundance of RpoD4 during the circadian cycle. An entrained wild-type strain was sampled at 4-h intervals between hours 4 and 52 in LL (200 microeinsteins m−2 s−1) and examined by immunoblot analysis with an RpoD4 antiserum (one sample was lost at 40 h). The posttransfer gel was stained with Coomassie blue to verify equal loading of protein samples. White and hatched bars indicate time points corresponding to subjective day and night, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism by which temporal information is transduced to downstream genes in S. elongatus poses a dilemma because circadian control is not limited to a small subset of genes; rather, it pervades expression of the entire genome (20). Although the transcriptional level is not the only level at which gene expression may be regulated by the clock, it is the control point most readily assayed via luciferase reporter genes in which the cyanobacterial promoter is the only variable among tested loci. A large body of reporter data showing rhythmic bioluminescence from defined promoters and from randomly sampled genomic segments suggests that the fundamental transcription machinery (RNA polymerase [RNAP] core plus sigma factors) is important in maintaining wild-type circadian rhythmicity.

Our working model for the global regulation of gene expression by the circadian clock is that the transcription apparatus oscillates in a circadian manner, in phase with the class 1 (peak at dusk) genes (20). There may be accessory (transcription) factors that modulate specific circadian properties, e.g., the opposite-phase expression of PpurF::luxAB or the high-amplitude expression of PkaiB::luxAB. We propose that changes in the pool of sigma species during the circadian cycle are at least partially responsible for global circadian expression.

We found that removal of any single group 2 sigma factor modifies expression from the psbAI gene of S. elongatus and that different aspects of the circadian rhythm can be affected: the circadian period, the amplitude of the oscillation, and the relative phasing of the peaks. These data suggest an important role for sigma factors in the circadian regulation of gene expression. Because all individual and pairwise sigma factor gene inactivations affected PpsbAI expression, we expect that the psbAI promoter is recognized by all four group 2 sigma factors. This is consistent with previously reported genetic data for overall expression in sigma mutant backgrounds (24) and with biochemical evidence that the holoenzymes reconstituted with RpoD1, RpoD3, or RpoD4 all recognized a number of S. elongatus and E. coli promoters, albeit with different preferences (7).

Our data are most consistent with a model in which different sigma factors compete for association with the core RNAP, such that the composition of the holoenzyme pool varies over a CT scale. Temporal changes in the relative abundance of active sigmas, and differences among them in affinity for specific promoters, could account, at least in part, for individualized patterns of gene expression in an overall rhythmic background. In Arabidopsis, the circadian waves of members of a putative signal transduction protein family have been proposed as conveyors of temporal information (21). The expression of five members of the APRR1/TOC1 family of pseudo response regulators is coordinated in a circadian manner with the abundance of each message peaking at a distinct time. The authors propose a bar code model to explain how CT might be read out based on the relative abundance of these factors (21). Expression patterns of PrpoD2, PrpoD3, and PsigC fusions to the luxAB gene set showed no evidence for a progressive change from one sigma factor to another at different times during the circadian cycle; all showed peaks of expression in the class 1 phase (Fig. 4A). However, even though transcriptional peaks of these sigma factors are not differently phased, their activities, such as ability to associate with the RNAP core, may vary on a CT scale.

From immunoblot analysis, the protein level of RpoD4 oscillates with peaks of abundance near CT 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5), although the bioluminescence peaks from the majority of gene fusions are at CT 12 and 36 h, etc. Despite the robust cycling of RpoD4 evident in two experiments, oscillation was not obvious in another. Thus, changes in sigma factor protein abundance may not be necessary for circadian rhythmicity. Temporal changes in activity may occur that are not evident by immunoblot analysis. The inability to distinguish among sigma factors with existing antisera currently precludes determining whether the protein abundance oscillation phasing is different among the factors. Aside from absolute abundance changes, sigma factors may experience temporal regulation of activity. For example, sigmas may be sequestered and rendered inactive by anti-sigma factors, as occurs in many developmental systems (9). A search of the genome of another cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, revealed two predicted anti-sigma factors, slr1856 (homolog of an anti-sigma B factor antagonist) and slr1912 (homolog of an anti-sigma F factor antagonist) (14) (www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano). Complete genome analysis of S. elongatus PCC 7942 is under way and will determine whether the identification of this class of regulatory factors is present in S. elongatus (C. Holtman, P. Youderian, and S. S. Golden, unpublished data). Another regulatory mechanism for altering sigma activity has been proposed in plants in which phosphorylation states of sigma-like factors affects DNA binding characteristics in different plastid types (31).

None of the single or pairwise sigma factor gene disruptions severely reduced expression of PpsbAI, PpurF, or PkaiB reporter strains, indicating that the remaining sigma factors in the pool are capable of transcribing these promoters even if the usual mechanism involves progressive interchange of subunits during the circadian cycle.

Overexpression of RpoD3 resulted in arrhythmicity of a PpsbAI reporter strain (Fig. 3C). However, overexpression in the PkaiB::luxAB reporter strain decreased the magnitude and amplitude of the bioluminescence rhythm without abolishing it, indicating that intrinsic timing is still intact in this situation (Fig. 3E). The decreased amplitude of expression from PkaiB, which encodes a central component of the clock mechanism, may be sufficient to explain why the oscillation from PpsbAI, which is controlled by the clock but not part of the clock, becomes arrhythmic. Alternatively, the difference between a lower amplitude rhythm from PkaiB::luxAB and arrhythmia from PpsbAI::luxAB may merely reflect the lower amplitude of the wild-type psbAI oscillation.

The relative insensitivity of PkaiB expression to the loss of sigma factor genes supports the idea that this promoter is relatively insulated, or buffered, from other gene expression pathways (Fig. 1). However, the promoter for kaiA, which also encodes a clock component and is immediately upstream of kaiBC in the genome, shows the same sensitivity to output pathway mutations as does psbAI (15; this study and A. Sivan, N. Tsinoremas, and S. S. Golden, unpublished data [for mutations in the tnp5 gene]). These data indicate that PkaiA and PkaiB are on different regulatory circuits and that kaiA expression can be dramatically altered without changing the fundamental timing mechanism, even though KaiA is necessary for normal levels of PkaiB expression (10). The marked effect of rpoD3 and rpoD4 inactivation on the amplitude of oscillation and magnitude of expression for purF is the first evidence for a gene involved in the circadian expression of a class 2 (peaks at dawn) gene, although the sigma factors do not seem to regulate circadian phasing.

Inactivation of rpoD2 led to an approximately fourfold increase in expression from PrpoD2::luxAB (Fig. 4C). At this time we do not know whether the interaction of RpoD2 with its own promoter is biochemical or solely genetic. RpoN of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae strain VF39SM negatively autoregulates expression from rpoN by binding to its upstream region (5), but the RpoD2 data could be explained as easily by an indirect mechanism.

The sigC null mutation caused the period of PpsbAI expression to be longer than those of PkaiB and PpurF (Fig. 1D, H, and L). These results reveal that it is possible for multiple timing circuits to coexist in S. elongatus. The first report that clearly demonstrates the presence of two oscillations with different circadian periods in one cell is from the unicellular alga Gonyaulax polyedra (27). In this organism, rhythms of bioluminescence and aggregation run with different periods, and the authors proposed that each rhythm is controlled by its own separate oscillator (27).

This phenomenon is not limited to sigC disruption. The inactivation of rpoD3 dissimilarly affects even different segments of the psbAI regulatory region: it shortened the period of the bioluminescence rhythm by ∼1 h (23.9 ± 0.2 h versus 25.0 ± 0.3 h, n = 10) in a reporter strain that bears the −54 to +43 element of PpsbAI fused to luxAB (data not shown); however, it advanced the relative phase of expression by about 4 h without affecting the period in a reporter strain that carries a longer upstream region (−185 to +224 element of PpsbA) (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the rpoD2 sigC double mutation led to an ∼1.5-h-long period of PpsbAI::luxAB expression but had no significant effect on the period of expression of the PpurF::luxAB and PkaiB::luxAB strains, confirming the ability of mutations to differentially affect the circadian periods of different reporters (Fig. 2D). These results reveal that it is possible for multiple timing circuits to coexist in the cell and that there is flexibility in circadian timing in S. elongatus.

A comprehensive model for the roles of sigma factors in circadian control of gene expression must account for the dissimilar effects on different promoters, the ability to control genes with timing circuits of different periods, and increased expression from some genes when a sigma factor is missing. The data describe a complex network in which both direct and indirect effects of changes in gene expression are likely to contribute to the observed phenotypes. Direct assay of the RNAP holoenzyme and its sigma factor constituents over time will contribute greatly to assembling the puzzle and determining whether the basic tenets of the model are correct.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kan Tanaka (University of Tokyo) for plasmids that carry the rpoD2, rpoD3, and rpoD4 genes; for the sequences of those plasmids; and for antisera directed against their products. We thank Jim Golden for helpful advice regarding the organization of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (P01 NS39546) and NSF (MCB-9982852) to S.S.G. J.L.D. is a fellow of the NSF (PA 99-025).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, C. A., N. F. Tsinoremas, J. Shelton, N. V. Lebedeva, J. Yarrow, H. Min, and S. S. Golden. 2000. Application of bioluminescence to the study of circadian rhythms in cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 305:527-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell-Pedersen, D., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 1996. Distinct cis-acting elements mediate clock, light, and developmental regulation of the Neurospora crassa eas (ccg-2) gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:513-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustos, S. A., and S. S. Golden. 1991. Expression of the psbDII gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 requires sequences downstream of the transcription start site. J. Bacteriol. 173:7525-7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bustos, S. A., and S. S. Golden. 1992. Light-regulated expression of the psbD gene family in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942: evidence for the role of duplicated psbD genes in cyanobacteria. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232:221-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, S. R., I. J. Oresnik, and M. F. Hynes. 2001. RpoN of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae strain VF39SM plays a central role in FnrN-dependent microaerobic regulation of genes involved in nitrogen fixation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:623-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elledge, S. J., P. Sugiono, L. Guarente, and R. W. Davis. 1989. Genetic selection for genes encoding sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3689-3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goto-Seki, A., M. Shirokane, S. Masuda, K. Tanaka, and H. Takahashi. 1999. Specificity crosstalk among group 1 and group 2 sigma factors in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942: in vitro specificity and a phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 34:473-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harmer, S. L., J. B. Hogenesch, M. Straume, H. S. Chang, B. Han, T. Zhu, X. Wang, J. A. Kreps, and S. A. Kay. 2000. Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science 290:2110-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes, K. T., and K. Mathee. 1998. The anti-sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:231-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiura, M., S. Kutsuna, S. Aoki, H. Iwasaki, C. R. Andersson, A. Tanabe, S. S. Golden, C. J. Johnson, and T. Kondo. 1998. Expression of a clock gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science 281:1519-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki, H., Y. Taniguchi, M. Ishiura, and T. Kondo. 1999. Physical interactions among circadian clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 18:1137-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwasaki, H., S. B. Williams, Y. Kitayama, M. Ishiura, S. S. Golden, and T. Kondo. 2000. A KaiC-interacting sensory histidine kinase, SasA, necessary to sustain robust circadian oscillation in cyanobacteria. Cell 101:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, C. H., and S. S. Golden. 1999. Circadian programs in cyanobacteria: adaptiveness and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:389-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko, T., S. Sato, H. Kotani, A. Tanaka, E. Asamizu, Y. Nakamura, N. Miyajima, M. Hirosawa, M. Sugiura, S. Sasamoto, T. Kimura, T. Hosouchi, A. Matsuno, A. Muraki, N. Nakazaki, K. Naruo, S. Okumura, S. Shimpo, C. Takeuchi, T. Wada, A. Y. Watanabe, M. Yamada, M. Yasuda, and S. Tabata. 1996. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 3:109-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katayama, M., N. F. Tsinoremas, T. Kondo, and S. S. Golden. 1999. cpmA, a gene involved in an output pathway of the cyanobacterial circadian system. J. Bacteriol. 181:3516-3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo, T., T. Mori, N. V. Lebedeva, S. Aoki, M. Ishiura, and S. S. Golden. 1997. Circadian rhythms in rapidly dividing cyanobacteria. Science 275:224-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo, T., N. F. Tsinoremas, S. S. Golden, C. H. Johnson, S. Kutsuna, and M. Ishiura. 1994. Circadian clock mutants of cyanobacteria. Science 266:1233-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulkarni, R. D., and S. S. Golden. 1997. mRNA stability is regulated by a coding-region element and the unique 5′ untranslated leader sequences of the three Synechococcus psbA transcripts. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1131-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kutsuna, S., T. Kondo, S. Aoki, and M. Ishiura. 1998. A period-extender gene, pex, that extends the period of the circadian clock in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 180:2167-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Y., N. F. Tsinoremas, C. H. Johnson, N. V. Lebedeva, S. S. Golden, M. Ishiura, and T. Kondo. 1995. Circadian orchestration of gene expression in cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 9:1469-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsushika, A., S. Makino, M. Kojima, and T. Mizuno. 2000. Circadian waves of expression of the APRR1/TOC1 family of pseudo-response regulators in Arabidopsis thaliana: insight into the plant circadian clock. Plant Cell Physiol. 41:1002-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel, K.-P., and E. K. Pistorius. 1992. Isolation of a photosystem II associated 36 kDa polypeptide and an iron stress 34 kDa polypeptide from thylakoid membranes of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC 6301 grown under mild iron deficiency. Z. Naturforsch. Teil C 47:867-874. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulvey, M. R., and P. C. Loewen. 1989. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel sigma transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:9979-9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair, U., C. Thomas, and S. S. Golden. 2001. Functional elements of the strong psbAI promoter of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 183:1740-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiwaki, T., H. Iwasaki, M. Ishiura, and T. Kondo. 2000. Nucleotide binding and autophosphorylation of the clock protein KaiC as a circadian timing process of cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:495-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittendrigh, C. S. 1981. Circadian systems: general perspective and entrainment, p. 57-80 and 95-124. In J. Aschoff (ed.), Handbook of behavioral neurobiology: biological rhythms, vol. 4. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 27.Roenneberg, T., and D. Morse. 1993. Two circadian oscillators in one cell. Nature 362:362-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaefer, M. R., and S. S. Golden. 1989. Light availability influences the ratio of two forms of D1 in cyanobacterial thylakoids. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7412-7417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz, O., M. Katayama, S. B. Williams, T. Kondo, and S. S. Golden. 2000. CikA, a bacteriophytochrome that resets the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Science 289:765-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka, K., S. Masuda, and H. Takahashi. 1992. Multiple rpoD-related genes of cyanobacteria. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56:1113-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiller, K., and G. Link. 1993. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation affect functional characteristics of chloroplast and etioplast transcription systems from mustard (Sinapis alba L.). EMBO J. 12:1745-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsinoremas, N. F., M. Ishiura, T. Kondo, C. R. Andersson, K. Tanaka, H. Takahashi, C. H. Johnson, and S. S. Golden. 1996. A sigma factor that modifies the circadian expression of a subset of genes in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 15:2488-2495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, Y., T. Mori, and C. H. Johnson. 2000. Circadian clock-protein expression in cyanobacteria: rhythms and phase setting. EMBO J. 19:3349-3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, Y., D. W. Piston, and C. H. Johnson. 1999. A bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) system: application to interacting circadian clock proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:151-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu, H., M. Nowrousian, D. Kupfer, H. V. Colot, G. Berrocal-Tito, H. Lai, D. Bell-Pedersen, B. A. Roe, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2001. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from two starvation, time-of-day-specific libraries of Neurospora crassa reveals novel clock-controlled genes. Genetics 157:1057-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]