Abstract

Three oligomeric forms of colicin A with apparent molecular masses of about 95 to 98 kDa were detected on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels loaded with unheated samples from colicin A-producing cells of Escherichia coli. These heat-labile forms, called colicins Au, were visualized both on immunoblots probed with monoclonal antibodies against colicin A and by radiolabeling. Cell fractionation studies show that these forms of colicin A were localized in the outer membrane whether or not the producing cells contained the cal gene, which encodes the colicin A lysis protein responsible for colicin A release in the medium. Pulse-chase experiments indicated that their assembly into the outer membrane, as measured by their heat modifiable migration in SDS gels, was an efficient process. Colicins Au were produced in various null mutant strains, each devoid of one major outer membrane protein, except in a mutant devoid of both OmpC and OmpF porins. In cells devoid of outer membrane phospholipase A (OMPLA), colicin A was not expressed. Colicins Au were detected on immunoblots of induced cells probed with either polyclonal antibodies to OmpF or monoclonal antibodies to OMPLA, indicating that they were associated with both OmpF and OMPLA. Similar heat-labile forms were obtained with various colicin A derivatives, demonstrating that the C-terminal domain of colicin A, but not the hydrophobic hairpin present in this domain, was involved in their formation.

Colicins are proteins produced by strains of Escherichia coli carrying a colicinogenic plasmid and lethal for related E. coli strains. They are classified into two groups according to various characters. Colicins of group A are secreted, but those of group B are not. The mechanism of secretion of group A colicins is unknown. It involves one lipopeptide, called colicin lysis protein, which is expressed with the colicin. The colicin lysis proteins are thought to allow colicins to cross both the inner and outer membranes of E. coli and to release them in the medium late after synthesis (reviewed in references 14 and 46).

Colicin A is a group A colicin. It is a pore-forming protein of 63 kDa, organized into three domains, like all colicins. It is produced in huge amounts during the SOS response along with the colicin A lysis protein, called Cal. Cal is synthesized as a precursor that is acylated and processed in the inner membrane before being exported to the outer membrane. Colicin A has been shown to accumulate in the cytoplasm before being released in the medium with the help of Cal at the end of induction (12).

High-molecular-mass forms of colicin A have been detected in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gels loaded with unheated samples of producing cells (9, 31). They are poorly stained by Coomassie brilliant blue but can be visualized either on Western blots of the gels probed with antibodies to colicin A or on autoradiograms of gels loaded with cells labeled with radioactive amino acids. In this study, the heat-labile forms of colicin A were studied in induced cells of E. coli W3110(pColA9) and characterized by their electrophoretic mobility in SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Cell fractionation studies revealed that they were localized in the outer membrane whether or not the producing cells contained the cal gene. The heat-modifiable electrophoretic mobility of these colicin A forms was a consequence of their location in the outer membrane, as heat-modifiable gel migration is a characteristic common among outer membrane proteins (7, 23, 29, 36, 37, 42). Colicin A thus appeared to be able to reach the outer membrane without the help of Cal. As colicin A is a globular protein with no signal sequence, it seemed unlikely that it could spontaneously reach the outer membrane. Therefore, the role of various outer membrane proteins during export was investigated by testing mutants devoid of one specific outer membrane protein. The heat-labile forms of colicin A were absent in cells devoid of both OmpC and OmpF porins and in cells devoid of outer membrane phospholipase A (OMPLA). However, in pldA null mutants, induction of colicin A expression did not occur. The heat-labile forms of colicin A reacted with antibodies to colicin A, to OmpF, and to OMPLA, indicating that they were tightly associated with porins and with OMPLA. Based on these observations, the mechanism of export and the physiological role of the heat-labile species of colicin A are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli K12 W3110 (Nalr), W3110 degP, W3110 pldA, MC4100, MC4100 9301 ompF, MC4100 MH764 ompC, MC4100 G11e1 btuB, UT5600 ompT, and JE5505 lpp were from the lab collection. E. coli JC8931 ompA and JC7752 pal were a gift from Jean-Claude Lazzaronni. E. coli BZB3000 and BZB1107 ompF were a gift from Roland Lloubès (22). E. coli CE1347 ΔpldA::Kan was a gift from H. M. Verheij (7). The null mutation ΔpldA::Kanr was transferred to W3110 by P1 transduction. The plasmid pColA9 contains the wild-type colicin A operon. The plasmids pColA9F1 and pJMM1 contain the colicin A operon from which the cal gene has been deleted. Plasmids containing an in-frame deletion within the caa gene which encodes colicin A, a protein of 592 amino acids, have been constructed from pColA9. The plasmids pAR1, pVC44, and pBC7 contain the colicin A operon with a deletion in the caa gene corresponding to amino acids 31 to 173 (Δ31-173), 70 to 370 (Δ70-370), and 172 to 592 (Δ172-592) of colicin A, respectively (2). The plasmid pX345 contains a frameshift within the caa gene which substitutes 26 residues for the last 42 residues of colicin A (550 to 592) (1).

Growth conditions.

Strains were grown at 37°C with shaking in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in M9 minimal medium supplemented with thiamine (1 μg/ml), lactate (0.4%, vol/vol) and Casamino Acids (0.01%, wt/vol). Cultures with an optical density at 600 nm of 1 were induced with mitomycin C at 300 ng/ml for 3 h. Globomycin, a gift from M. Inukai (Sankyo and Co., Ltd, Japan), was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (5 mg/ml) and added to the cultures 15 to 20 min after induction at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Either EDTA (1 mM) or sodium azide (2 mM) was added at zero time of induction.

Colicin A activity.

Aliquots of 2 μl of a colicin A solution were spotted onto a lawn of MC4100 cells spread on LB agar plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, clear zones of growth inhibition were observed.

Cell fractionation.

Cells grown in LB medium were induced with mitomycin C for 90 min. They were pelleted by centrifugation and submitted to spheroplasting followed by osmotic shock as described by Osborn et al. (38). The envelope fraction was resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2)-5 mM MgCl2-2% Triton X-100 to solubilize inner membrane proteins. The insoluble outer membrane fraction was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 15,000 × g, washed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) containing 5 mM MgCl2, and resuspended in the same buffer. Polyclonal antibodies (PAbs) to OsmY, GroEL, and OmpF were used to monitor fractionation of the periplasm, the cytoplasm, and the outer membrane, respectively.

Density gradient flotation was carried out as described previously (17). A 50-ml culture of UT5600(pColA9) in LB medium was induced for 90 min with mitomycin C, washed in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2), resuspended in 2 ml of buffer, and broken in a French press. Broken cells were layered at the top of a Beckman SW41 centrifuge tube containing successive overlays with 1-ml aliquots of 60, 56, 53, 50, 47, 44, 41, 38, 35, and 28% (wt/wt) sucrose in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2). Centrifugation was carried out in a SW41 rotor at 76,400 × g for 15 h at 10°C. Fractions were removed from the top of the gradient in 500-μl increments with a Buchler Auto Densi-Flow II machine. Ten microliters of each fraction was used for determination of NADH oxidase activity as described previously (38).

Urea extraction of outer membranes.

Urea treatment of outer membranes was performed as described previously (29). Outer membrane preparations (20 μl) were mixed with 60 μl of 8 M urea in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) and incubated on ice for 30 min. They were then reisolated by ultracentrifugation (30 min, 75,000 × g, TLA 100.2 rotor; Beckman) at 4°C and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2).

Pulse-chase experiments.

Cells grown in M9 medium and induced with mitomycin C for 60 min were labeled with a 35S protein labeling mix (1,175 Ci/mmol) at 20 μCi/ml (1 μCi = 37 kBq) for various times and then chased with a mixture of cold methionine and cold cysteine (50 μg/ml). Radioactive products were purchased from NEN. In routine experiments, 15-μl samples of the cultures were taken at various times after the chase and mixed with 10 μl of sample buffer. The samples were diluted 10 times in the same solution (1.5 vol of M9 medium/1 vol of sample buffer) before being heated for 4 min to 96°C, as necessary, and loaded on 6% polyacrylamide-SDS gels.

Protein analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described previously (9). Routinely, 15 μl of culture after 3 h of induction was mixed with 10 μl of sample buffer. A 2-μl portion of this suspension was diluted 10 times in the same solution (1.5 vol of LB medium/1 vol of sample buffer) before being heated for 4 min to 96°C, as necessary, and loaded either on an SDS gel containing 6% acrylamide or on a urea-SDS gel containing 7% acrylamide and 7 M urea. Proteins in unstained gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (200-nm pore size; Schleicher & Schuell, Inc.). The membranes were incubated first with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to colicin A (MAb 1C11 at 1:5,000 or 9E2 at 1:500) or PAbs to OmpF at 1:1,000 (8) and then with phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies as appropriate. Protein bands were visualized by incubation with Nitro Blue Tetrazolium in the presence of MgCl2 and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate disodium salt.

RESULTS

Heat-labile forms of colicin A.

After induction by mitomycin C of E. coli W3110(pColA9) bacteria, colicin A rapidly becomes the major cell protein and is detected as a thick band with an apparent molecular mass of 60 kDa on SDS gels stained with Coomassie blue (9, 12). In order to increase the resolution, small volumes of an induced LB culture of E. coli W3110(pColA9) were loaded onto SDS gels containing only 6% acrylamide. Colicin A could not then be seen by Coomassie blue staining and was instead immunodetected by the MAb 1C11, which has high affinity for colicin A (24). Various species of colicin A were detected. They were mainly two monomer forms with apparent molecular masses of 60 and 61 kDa, called colicin Af (i.e., fast migration) and colicin As (i.e., slow migration), and various oligomeric forms with apparent molecular masses of 120 to 135 kDa, called collectively colicins Ao (i.e., oligomers) (Fig. 1). All these colicin A forms were detected whether or not the sample loaded on the SDS gels had been heated in sample buffer.

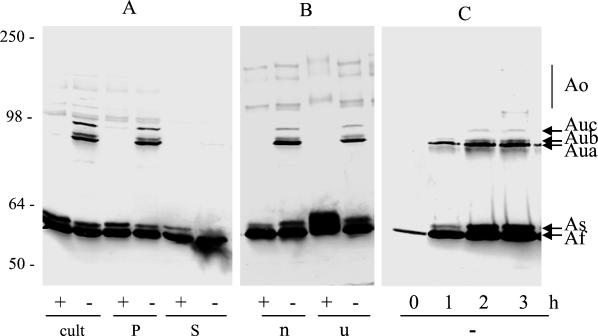

FIG. 1.

Heat-labile forms of colicin A in producing E. coli cells. W3110(pColA9) cells were induced with mitomycin C. (A) After 3 h of induction, samples were taken and centrifuged. Samples of the culture (cult), cell pellet (P), or supernatant (S) were mixed with sample buffer and heated 4 min to 96°C (+) or left unheated (−) before loading on an SDS gel. (B) Samples were mixed in either normal sample buffer (n) or sample buffer containing urea (5 M final concentration; u) before being heated (+) and loaded. (C) At various times after induction, samples were mixed with sample buffer and loaded without heating (−) onto the gel. Western blots of the gels probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A are presented. Numbers on the left are the molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of the standard proteins.

Different high-molecular-weight forms of colicin A were detected on the immunoblots of the gels in samples of the induced W3110(pColA9) cells which had not been boiled in SDS before being loaded onto gels (Fig. 1A). These heat-labile forms were called colicins Au (i.e., unheated). They consisted of three bands with similar apparent molecular masses, two near 95 kDa and one near 98 kDa. Their molecular masses did not correspond to those of dimers of colicin A. They were observed in samples in SDS in the presence of urea (Fig. 1B) and when heated to 70°C (data not shown) but not in samples heated to 96°C. Of the two bands at 95 kDa, the one with the greatest electrophoretic mobility was the major form and was designated Aua. The second one was called Aub. The band at 98 kDa was designated colicin Auc. It was more heat stable than the two other bands, as it was observed in culture samples kept 1 min at 96°C (data not shown). It was present in smaller amounts than the colicins Aua and Aub.

The three colicins Au were detectable soon after induction. Their amount increased with time, but their proportions remained stable (Fig. 1C). At the end of induction, their amounts were significant (10 to 20% of the total amount of colicin A) in the culture and in the cells pelleted by centrifugation but not in the medium (Fig. 1A). They seemed either to be released less efficiently than the other forms of colicin A or to dissociate into monomers during or after release into the medium.

These various forms of colicin A were found in induced W3110 cells carrying pColA9, pColA9F1, or pJMM1, that is, carrying a plasmid containing a colicin A operon with or without the cal gene. They were found whether cells were grown on LB or M9 medium at 30, 37, or 42°C, as well as in cells treated with globomycin, sodium azide, EDTA, or Mg2+ ions, products that have been shown to influence colicin A induction (10). They were similarly detected by anti-colicin A PAbs and by the MAbs 1C11 and 9E2, directed against the N- and the C-terminal parts of colicin A, respectively (data not shown).

Radiolabeling of colicins Au.

Pulse-chase experiments were performed to study the kinetics of synthesis of colicins Au. Induced W3110(pColA9) cells grown in M9 medium were labeled with a 35S protein labeling mix for 15 s. Samples were taken at various times during the chase and analyzed on SDS gels. On the autoradiogram of the gel (Fig. 2A), monomeric colicin A was the most intensely labeled band from the first 30 s of chase in the induced cells. It was found in both the heated and the unheated samples of the induced culture. In the unheated samples of the induced cells, two bands migrating at 95 kDa were observed after the first 30 s of chase. They were absent in the uninduced cells and they corresponded in position to colicins Aua and Aub on the immunoblot of the radioactive gel (data not shown). The fastest-migrating one was the major form. The two bands remained stable during the chase.

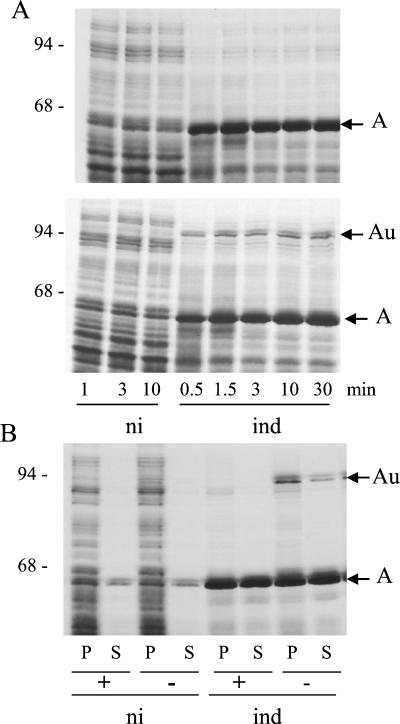

FIG. 2.

Radiolabeling of colicins Au in producing cells. W3110(pColA9) cells grown in M9 medium were induced (ind) with mitomycin C or not induced (ni). (A) After 1 h of induction, 35S protein labeling mix was added and chased 15 s later. At the indicated times during the chase, samples were suspended in sample buffer and heated (top) or not (bottom) before being loaded onto an SDS gel. (B) 35S protein labeling mix was added and chased 5 min later. Samples taken after 150 min of the chase were centrifuged. The cell pellet (P) and the supernatant (S) were mixed with sample buffer and heated (+) or left unheated (−) before being loaded onto a gel. The autoradiograms of the gels are presented. Numbers on the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins.

By 3 h after induction, colicins Au were observed in the pellet and the supernatant of the induced cells, but in lower amount in the supernatant than in the cell pellet (Fig. 2B). Colicin Auc was not observed under these labeling conditions due to its low level of synthesis, though it was observed on the immunoblot of the gel (data not shown).

Cellular localization of colicins Au.

The subcellular localization of colicins Au was determined in W3110(pColA9) cells grown in LB and induced with mitomycin C for 90 min. By this time of induction, the amount of colicin A in the cell had reached its maximum, but colicin release into the medium had not started. Cells were fractionated by spheroplasting, osmotic shock lysis, and solubilization by Triton X-100 (38). The various fractions were analyzed under the conditions described above (Fig. 3). All cell fractions contained active colicin A. Among the unheated samples of each cell compartment, only the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction contained colicins Au in large amounts. In this fraction, they constituted almost the totality of colicin A present in the unheated sample, while monomeric colicin A was found in the heated sample. Thus, colicins Au were transformed in monomers of colicin A after thermal unfolding in SDS.

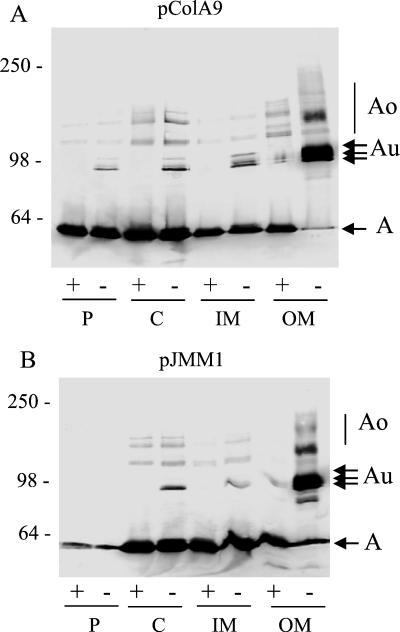

FIG. 3.

Cellular localization of colicins Au. Cells induced with mitomycin C for 90 min were fractionated by spheroplasting and osmotic shock. Samples of the periplasm (P), the cytoplasm (C), the inner membrane (IM), and the outer membrane (OM) were mixed with sample buffer and heated (+) or not (−) before loading onto an SDS gel. (A) W3110(pColA9) cells; (B) W3110(pJMM1) cells. Western blots of the gels probed with MAb 1C11 are presented. Numbers on the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins.

The localization of the various forms of colicin A was similar in W3110 cells carrying either pColA9, which contains the wild-type colicin A operon (Fig. 3A), or pJMM1, which contains a colicin A operon with the cal gene deleted (Fig. 3B). However, smaller amounts of colicin A were found in the periplasm of W3110(pJMM1) cells than in that of W3110(pColA9) cells. The cal gene product could play a role in the export of colicin A to the periplasm but did not seem to be needed to send it to the envelope. The presence in the periplasm of cloacin DF13 has been previously observed (39).

Assembly of colicins Au into the outer membrane.

Colicins Au detected in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction could be aggregated colicin A that pelleted with the membrane during centrifugation. In order to determine whether colicins Au were correctly assembled into the outer membrane, the outer membrane fraction of W3110(pColA9) cells was treated with 8 M urea for 30 min before being reisolated by ultracentrifugation. Colicins Au were again detected in the unheated samples of the pellet, as seen after gel and immunoblot analysis (data not shown). The resistance of colicins Au to urea indicated that they were assembled in the outer membrane.

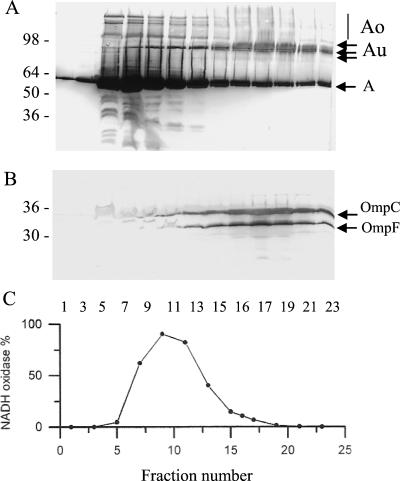

To confirm the subcellular localization of colicins Au, sucrose gradient centrifugation was performed on membranes from induced UT5600(pColA9) cells. The gradient fractions were analyzed on urea-SDS gels in order to detect both porins of the outer membrane (6). As seen on immunoblots, all the fractions contained various forms of colicin A (Fig. 4A) and all contained active colicin A. Colicins Au were located in high-density fractions, whereas monomeric colicins A were preferentially found in low-density fractions. Fractions containing colicins Au also contained the porins OmpC and OmpF (Fig. 4B), but not NADH oxidase activity (Fig. 4C). Thus, colicins Au appeared to be associated with the outer membrane. Their electrophoretic migration is similar to that of outer membrane proteins, whose migration in SDS gels varies greatly when they are boiled in the sample buffer, the unfolded forms migrating differently than the folded ones and monomeric forms migrating faster than the oligomeric ones (7, 29, 36, 37, 42).

FIG. 4.

Subcellular localization of colicins Au determined by flotation sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Induced W3110(pColA9) cells were disrupted in a French press and were layered onto a 28-to-60% (wt/wt) sucrose step gradient. Samples of the fractions were analyzed on urea-SDS gels. (A) Western blot of the gel loaded with unheated samples probed with MAb 1C11; (B) blot of the gel loaded with heated samples probed with PAbs to OmpF. Numbers on the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins. (C) NADH oxidase activity measured in each sample.

Production of colicins Au in mutants devoid of outer membrane proteins.

If colicins Au were heterodimers formed with colicin A linked to an outer membrane protein, they should not be produced in cells with mutations in that outer membrane protein. To identify this protein, pColA9 was introduced into cells with deletions of specific major outer membrane proteins. Transformants were induced for colicin A production and analyzed on gels and immunoblots as described above.

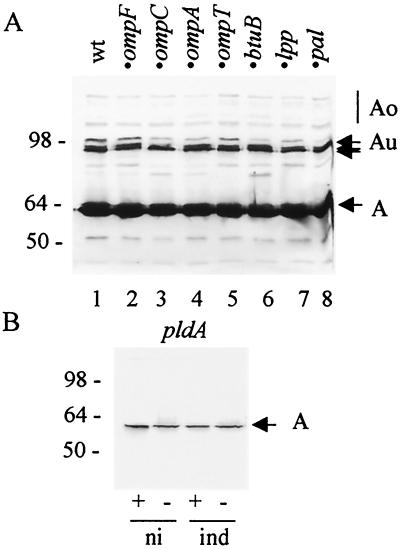

Colicins Au were detected in all null mutant strains tested as in the wild type, though with some quantitative differences (Fig. 5A). They were produced in induced E. coli cells: 9301, devoid of the porin OmpF; MH764, devoid of the porin OmpC; JC8931, devoid of the porin OmpA; UT5600, devoid of the protease OmpT; G11e1, devoid of the porin BtuB; JE5505, devoid of the lipoprotein Lpp; and JC7752, devoid of the lipoprotein Pal. No outer membrane proteins deleted in the mutants tested seemed to be required for the formation of colicins Au.

FIG. 5.

Production of colicins Au in E. coli cells devoid of one outer membrane protein. (A) Various mutated cells carrying pColA9 were induced with mitomycin C for 3 h. Aliquots of 2 μl of each culture (5 μl of 9301 ompF) were mixed with sample buffer and loaded onto an SDS gel without heating. Lanes: 1, W3110 (wild type [wt]); 2, MC4100 9301 ompF; 3, MC4100 MH764 ompC; 4, JC8931 ompA; 5, UT5600 ompT; 6, MC4100 G11e1 btuB; 7, JE5505 lpp; 8, JC7752 pal. (B) W3110 pldA::Kan(pColA9) cells were induced (ind) with mitomycin C for 3 h or not induced (ni). Aliquots of 10 μl were mixed with sample buffer and heated (+) or left unheated (−) before loading. Western blots of the gels probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A are presented.

Production of colicins Au was also tested in a mutant devoid of OMPLA (outer membrane phospholipase A). Cells of W3110 ΔpldA::Kan cells were transformed with either pColA9 or pJMM1, but the transformants were unstable, suggesting that the plasmids were lethal for the cells. Induction of colicin A in W3110 ΔpldA::Kan(pColA9) cells was drastically impaired, and only traces of monomeric colicin A were found in the induced as in the noninduced cells on immunoblots (Fig. 5B). That was surprising, as colicin A is produced in W3110 pldA cells, which contain a missense mutation in the pldA gene and have an inactive OMPLA (11, 28), although with a longer delay and at a lower level than in wild-type cells (10). Thus, the protein OMPLA, rather than its activity, seemed to be required for colicin A induction. Its absence might cause more significant cell perturbations than the loss of its activity, which has been shown to induce stress regulons (34).

OmpF is associated with colicins Au.

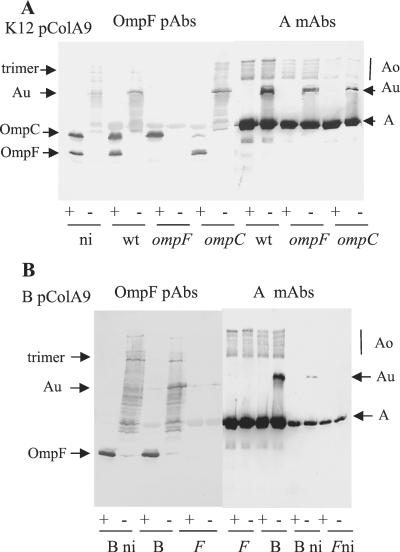

Colicin A production was reduced in 9301 ompF cells in such a way that twice the volume of the culture had to be loaded on gels as for the wild type (Fig. 5A). That suggested a role of OmpF in colicin A synthesis or stability. Thus, isogenic E. coli K-12(pColA9) cells, devoid of either OmpC or OmpF, were analyzed. Samples of the induced cultures were analyzed on urea-SDS gels in order to separate the porins OmpC and OmpF. The immunoblots were probed with PAbs to OmpF or MAbs to colicin A (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Colicins Au are not produced in cells devoid of OmpC and OmpF. Samples of cells carrying pColA9 were mixed with sample buffer and heated (+) or left unheated (−) before loading onto a urea-SDS gel. Western blots of the gels probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A and with PAbs to OmpF are presented. (A) K-12 pColA9 cells. W3110 (wild-type [wt]) cells were induced or not induced (ni). 9301 (ompF) and MH764 (ompC) cells were induced. (B) B(pColA9) cells. BZB3000 (B) and BZB1107 (ompF [F]) cells were induced or not induced (ni).

In the blot probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A, colicins A and Au were detected as in Fig. 5A. In the blot probed with an antiserum to OmpF, both OmpC and OmpF porins were detected in samples boiled in SDS before loading. OmpF migrated faster than OmpC, as expected (6). In the samples not heated in SDS before loading, a smear of proteins with an apparent molecular mass higher than 60 kDa was observed in cells containing OmpF, suggesting that it corresponded to various species of OmpF. In the smear, proteins with the same electrophoretic migration as colicins Au were detected in induced cells. They were faintly detected in uninduced cells, in which some spontaneous colicin A induction occurs. Their migration was faster than that of the OmpF trimers, whose apparent molecular masses are 120 to 130 kDa. Thus, some colicins Au seemed to be associated with OmpF in W3110 and MH764 ompC cells. In 9301 ompF cells, colicins Au were detected on the blot probed with MAbs to colicin A but not on the one probed with PAbs to OmpF. It might be that they are associated with OmpC, the only porin present, and the bound OmpC is not recognized by the PAbs to OmpF despite the homologies between the two porins. The PAbs recognize OmpC when it is unfolded after boiling in SDS, but they might not recognize it when it is partially unfolded or associated, as no smear of proteins similar to that observed in MH764 ompC is shown in uninduced (data not shown) or induced 9301 cells. Alternatively, colicins Au of 9301 ompF cells might be linked to an outer membrane protein(s) different from OmpC. The PAbs to OmpF recognized weakly monomeric colicin A on the blot as they recognized pure colicin A (data not shown).

Colicins Au are not produced in cells devoid of both OmpC and OmpF porins.

Cells of E. coli B contain only the OmpF porin. One mutant of the B strain devoid of OmpF, called BZB1107, has been constructed from BZB3000, a wild-type B strain (22). Both isogenic strains were transformed with pColA9 and analyzed as described above (Fig. 6B). On the blot probed with MAb 1C11, monomers of colicin A were detected in the same amount in both strains. Colicins Au were present in B cells as in W3110 cells, except for colicin Auc. In BZB1107 cells, no colicin Au was observed. On the blot probed with PAbs to OmpF, OmpF was detected in the heated samples of B cells and not in that of BZB1107 cells, as expected. In the unheated samples, no protein was detected in BZB1107 cells; in contrast, in the B cells, proteins which had the same migration as colicins Au were observed in the smear of proteins related to OmpF. They were present in greater amounts in induced cells than in uninduced ones. Bands which migrated at 130 kDa were present in both induced and uninduced B cells and corresponded to OmpF trimers. Thus, OmpF interacted with colicin A to produce colicins Aua and Aub. The absence of colicin Auc in the B cells suggested that it was formed by interaction between colicin A and OmpC, though that appeared to be inconsistent with the results obtained with ompC MH764 cells (Fig. 5A and 6A).

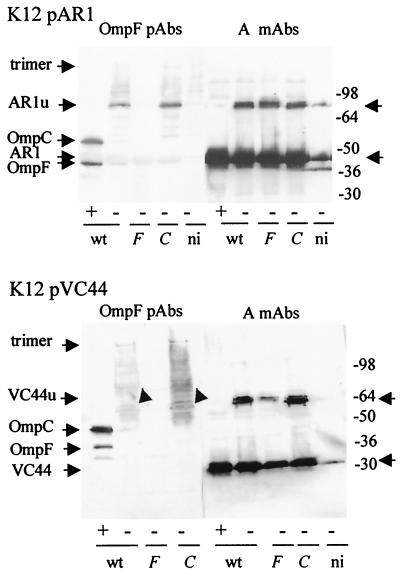

OmpF is required for the production of heat-labile forms of colicin A derivatives.

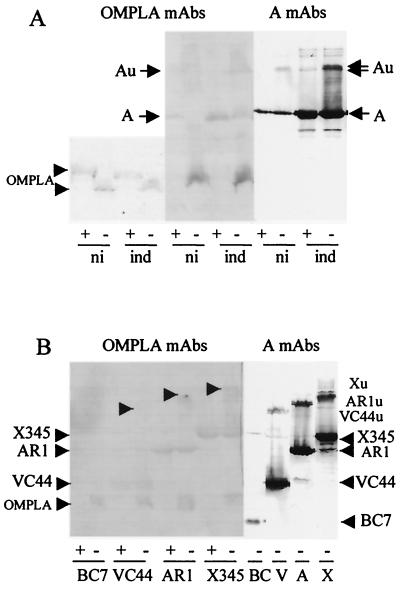

To confirm that the bands observed on the immunoblot probed with PAbs to OmpF were related to colicins Au, in-frame deletion derivatives of colicin A, whose heat-labile forms should migrate faster than those of colicin A, were studied. Colicin X345 (frameshift from residue 550 to 576) lacks the hydrophobic hairpin in the C-terminal domain, colicin AR1 (Δ31-173) lacks part of the translocation domain, colicin VC44 (Δ70-370) lacks the receptor binding domain, and colicin BC7 (Δ172-592) lacks the receptor and the pore-forming domains. All these colicin A derivatives are recognized by the MAb 1C11.

Strains W3110, 9301 ompF, and MH764 ompC containing pAR1 or pVC44 were induced and analyzed as described above (Fig. 7). In the unheated samples of the three strains producing colicin AR1 (Δ31-173), the MAb 1C11 detected monomers of 50 kDa and heat-labile oligomers of about 88 kDa, called AR1u. The PAbs to OmpF detected OmpC and OmpF as in Fig. 6A. In unheated samples of induced W3110 and MH764 ompC cells, they detected bands migrating at the same position as colicin AR1u. None was detected in induced 9301 ompF cells or in uninduced W3110 cells. Colicin VC44 (Δ70-370) of 32 kDa and its heat-labile oligomers with an apparent molecular mass of about 78 kDa, called VC44u, were detected by MAb 1C11 in the three strains tested. A smear that may include colicins VC44u was detected by the PAbs to OmpF in W3110 and MH764 ompC cells but not in 9301 ompF cells. Thus, OmpF was associated with the heat-labile forms of the colicin A derivatives as it was with the ones of colicin A. In strain 9301, devoid of OmpF, the heat-labile forms could be associated to OmpC which, for unknown reason, would not be recognized by the PAbs to OmpF.

FIG. 7.

Heat-labile forms of colicin A derivatives. K12 cells carrying pAR1 (top) or pVC44 (bottom) were analyzed on urea-SDS gels after being heated (+) or left unheated (−) prior to loading. W3110 (wild-type [wt]) cells were induced or not induced (ni). 9301 (F) and MH764 (C) cells were induced. Western blots of the gels probed with MAbs to colicin A and PAbs to OmpF are presented. Numbers on the right are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins.

Production of colicin A derivatives was analyzed in B and BZB1107 cells carrying pAR1, pVC44, or pBC7 (Fig. 8). The deletion-containing colicins AR1 (Δ31-173), VC44 (Δ70-370), and BC7 (Δ172-592) were produced in both strains. The heat-labile forms of colicins AR1 and VC44 were formed in B cells but not in BZB1107 cells. They were detected by OmpF PAbs, as they were in W3110 cells. Colicin BC7 (Δ172-592) did not form heat-labile oligomers. Colicin X345 (frameshift of 550 to 576) produced heat-labile forms which were recognized similarly to colicins Au on immunoblots in every strain tested (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Heat-labile forms of colicin A derivatives are not produced in cells devoid of OmpC and OmpF. (A) BZB3000 (wt B) cells carrying pColA9, pAR1, pVC44, or pBC7 were induced or not induced (ni) before being analyzed on a urea-SDS gel after being heated (+) or not prior to loading. (B) Same experiment with BZB1107 (ompF B) cells. The Western blots of the gels probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A and to PAbs to OmpF are presented. Numbers on the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins.

Hence, colicins Aus, AR1u, and VC44u contained OmpF associated with colicins A, AR1, and VC44, respectively. However, the difference between the apparent mass of the heat-labile forms and that of the monomeric forms of each colicin A derivative was not constant, as it should be if one specific protein were involved in the formation of the heat-labile forms.

On the blots (Fig. 7 and 8), the PAbs to OmpF recognized weakly monomeric colicin AR1 as well as monomeric colicin A (Fig. 6) but not monomeric colicin VC44. The PAbs reacted similarly with preparation of the colicins A and AR1 (data not shown), suggesting the presence of one recognized epitope(s) in the region deleted in VC44.

OMPLA interacts with colicins Au.

Production of colicin A was inhibited in cells devoid of OMPLA. To determine whether or not OMPLA was involved in the formation of colicins Au, analysis of the induced W3110(pColA9) cells were performed on immunoblots probed with MAbs to OMPLA (Fig. 9A). OMPLA was detected as a band of 31 kDa in the heated samples on the back side of the nitrocellulose membrane as it went through it (Fig. 9A) and as a band of 27 kDa in the unheated samples, as described previously (7). These bands were not detected in W3110 ΔpldA::Kan cells (data not shown). In addition, a band migrating as colicin A, i.e., 60 kDa, was detected by the MAbs in both unheated and heated samples of induced cells as was a faint band migrating as colicins Au in the unheated samples of induced cells but not in uninduced cells. Similar bands were observed in outer membrane fractions of induced UT5600 degP cells carrying pColA9 but not in cells with no plasmid (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

Heat-labile forms of colicin A and colicin A derivatives are detected by MAbs to OMPLA. (A) W3110(pColA9) cells were induced (ind) with mitomycin C or not induced (ni). They were analyzed on a SDS-9% polyacrylamide gel after being heated (+) or left unheated (−) prior to loading. (B) Induced W3110 cells carrying pX345, pAR1, pVC44, or pBC7 were analyzed as for panel A. Western blots of gels probed with MAb 1C11 to colicin A and with MAbs to OMPLA are presented. Part of the back of the blot probed with MAbs to OMPLA is presented (A, far left).

The band of 60 kDa detected by MAbs to OMPLA could not correspond to an OMPLA dimer, since the OMPLA dimer has to be cross-linked to be observed after activation of OMPLA (20). OMPLA is known to dimerize when activated (20, 45), and it is activated during colicin release, as reported previously (11, 21, 28, 41). But this band was detected in induced W3110(pJMM1) cells in which no colicin release took place (data not shown) and, consequently, in which OMPLA remains inactive, i.e., monomeric, suggesting that it corresponded to OMPLA linked to colicin A. Thus, OMPLA seemed to be associated with colicin A and to participate to the formation of colicins Au.

OMPLA is involved in the formation of heat-labile forms of colicin A derivatives.

To determine whether OMPLA is involved in the formation of the heat-labile forms of the colicin A derivatives, W3110 ΔpldA::Kan cells were transformed with various colicin A-encoding plasmids. Transformants with pX345, pAR1, or pVC44 were unstable, while transformants with pBC7 were stable. In the induced transformants, the production of colicins X345, AR1, and VC44 was drastically impaired, but not that of colicin BC7 (data not shown). That was unexpected, as W3110 pldA cells which contain an inactive OMPLA could be stably transformed with these plasmids and produced each colicin A derivative like the wild type, but in smaller amounts. OMPLA appears to be required for production of colicin A derivatives that produced heat-labile forms. Heat-labile forms might be toxic for producing cells in the absence of OMPLA.

The induced W3110 cells carrying pX345, pAR1, pVC44, or pBC7 were analyzed on SDS gels, and the immunoblots of the gels were probed with MAb to OMPLA (Fig. 9B). Monomeric OMPLA was detected as in Fig. 9A. In addition, a band migrating as the monomeric form of colicin A derivatives X345, AR1, and VC44 was detected by the MAb in both heated and unheated samples of induced cells. Furthermore, the MAbs recognized a faint band migrating as the heat-labile forms of colicins X345 (frameshift of 550 to 576), AR1 (Δ31-173), and VC44 (Δ70-370) in the unheated samples of the cells. No band was detected with colicin BC7 (Δ172-592), whose molecular mass is lower than that of OMPLA. Thus, OMPLA seemed to be associated with colicin A derivatives which produced heat-labile forms.

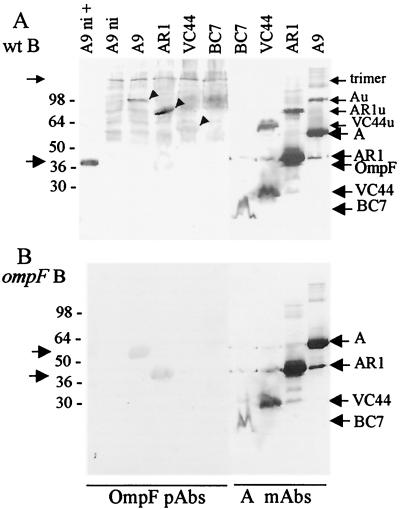

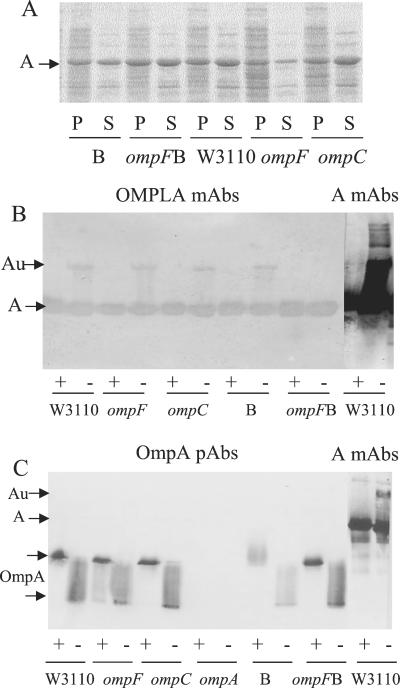

Colicins Au are not required for secretion.

Colicin A is secreted late after synthesis. To determine whether colicins Au were involved in the secretion, the cultures of the various strains studied were centrifuged 3 h after induction, and pellets and supernatants were analyzed on SDS gels stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 10A). All strains released colicin A, even BZB1107, which did not produce colicin Au. Thus, formation of colicins Au is not needed for colicin A secretion.

FIG. 10.

Colicins Au are not needed for secretion. (A) Cells carrying pColA9 were centrifuged after 3 h of induction. The pellet (P) and the supernatant (S) were analyzed on an SDS gel after heating in sample buffer. The relevant part of the gel stained by Coomassie blue is presented. (B) Western blots of the gel probed with MAbs to OMPLA and with MAb 1C11 to colicin A. (C) Western blot of the gel probed with MAbs to OmpA and with MAb 1C11 to colicin A. W3110 (wild-type), 9301 (ompF), MH764 (ompC), JC8931 (ompA), BZB3000 (B), and BZB1107 (ompF B) cells were analyzed after being heated (+) or left unheated (−) prior to loading.

All the strains tested contained OMPLA, which is involved in colicin secretion (11, 21, 28, 41). To determine whether OMPLA was associated with colicin A, the strains were analyzed on a urea-SDS gel, and the immunoblot of the gel was probed with MAbs to OMPLA (Fig. 10B). The MAbs recognized monomeric colicin A in the heated and unheated samples of each strain tested and colicins Au in the unheated samples, except in the unheated sample of BZB1107 cells. To confirm that the detection was specific, a similar blot was probed with PAbs to OmpA (Fig. 10C). The PAbs detected only OmpA as a 35-kDa band in the heated samples and as a 28-kDa smear in the unheated ones, as described previously (23), except in ompA JC8931 cells. Thus, the detection of colicin A by the MAbs to OMPLA indicated an association of OMPLA with colicin A in every strain.

DISCUSSION

Colicin A was found in various electrophoretic forms in extracts of producing E. coli cells. Three oligomeric forms, called colicins Au, exhibited heat-modifiable electrophoretic migration in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. They migrated in the gels with an apparent molecular mass of 95 to 98 kDa in unheated samples of cells and at the monomeric size of 60 kDa after heating. Their electrophoretic migration resembled that of outer membrane proteins, which migrate differently whether or not they are unfolded by heating in SDS (7, 23, 36, 37, 42). In fact, colicins Au were localized into the outer membrane of the cell. That was surprising, since colicin A does not have a signal sequence and is found in large amounts in the cytoplasm of the bacteria after induction of its synthesis (12). The assembly into the outer membrane of the colicins Au followed a rapid time course, as measured by the appearance of their heat-modifiable character. It was observed from the earliest time of chase after a 15-s pulse-labeling and remained stable whether or not the producing cells possessed a cal gene, i.e., possessed the colicin A export pathway. Their assembly in the outer membrane was a consequence of colicin A interaction with OmpC and OmpF porins and with OMPLA.

OmpF was shown to comigrate with colicins Au, as PAbs to OmpF recognized colicins Au on immunoblots. The colicins Au with very similar apparent molecular masses, Aua and Aub, might be colicin A associated with OmpF, a complex stable in urea and SDS but unstable after thermal unfolding in SDS. They were present in a K-12 mutant devoid of either OmpF or OmpC, suggesting that OmpC might substitute for OmpF, and vice versa, as these porins are homologous. The third colicin Au, Auc, had the highest apparent molecular mass. It is absent in B cells devoid of OmpC but present in an ompC K-12 mutant, indicating that it could not be colicin A associated with OmpC. An unidentified outer membrane protein might be linked to it. The three colicins Au were absent in cells devoid of both OmpC and OmpF, confirming that they contained porins. Thus, colicins Au corresponded to a heterogenous group of colicin A oligomers present in various amounts.

OMPLA was detected with both monomeric colicin A and colicins Au on immunoblots by MAbs to OMPLA, indicating that OMPLA interacts with colicin A and participate in the formation of colicins Au. However, OMPLA is a minor protein (43) and cannot be associated with the total amount of colicin Au. The instability of plasmids encoding colicin A or colicin A derivatives which produce heat-labile forms in a null pldA mutant confirms that OMPLA is required to the formation of Au species. It suggested that Au forms might be harmful for the cell in the absence of OMPLA.

Interaction of colicin A with either OmpF or OMPLA would take place when the proteins are newly synthesized. Newly synthesized OmpF and newly synthesized OMPLA might interact with newly synthesized colicin A and pilot it to the outer membrane to give colicins Au. OmpF is an abundant protein and would titrate colicins Au, explaining the large amount of colicins Au formed. The amounts of OmpF and OMPLA not associated with colicin A detected on immunoblots would be the amounts present in the cell before induction.

In colicins Au, OmpF and OMPLA may interact with the C-terminal domain of colicin A, as suggested by studies of the colicin A derivatives. That was unexpected, as OmpF is known to bind colicin A on sensitive cells (13, 15) but to the N-terminal domain during the translocation step of colicin A killing (3). The C-terminal domain of colicin A is composed of α-helices (40) and not β-sheets, as are outer membrane proteins (4, 18). Furthermore, it contains a hydrophobic helical hairpin that allows it to insert spontaneously into both inner membranes and lipid bilayers (25, 30, 33, 44). Such a hairpin could not constitute a signal for colicin A export to the outer membrane, as hydrophobic sequences have been shown to act as stop signals for protein export to the outer membrane (19, 36). A derivative of colicin A, called colicin X345 (frameshift from 550 to 576), devoid of the hydrophobic hairpin, was able to form heat-labile forms. The signal involved in colicin Au formation might be the long helix linking the C-terminal domain to the receptor domain observed in the structure of crystallized colicins (47, 48). It would be present in all colicins, since heat-labile forms have been observed in cells producing either a pore-forming colicin, such as colicins A and E1 (9), or a nuclease colicin, such as colicins E2 and E3 (data not shown).

Whether heat-labile forms are common to all colicins, they should have a function. The Au species formed of colicin A and porin play no role in secretion, since release of colicin A occurs in BZB1107 cells, which are devoid of it. Colicins Au are stable, indicating that colicin A is not exported to the outer membrane prior to release. The quantities of colicins Au found in the medium could be due to the formation of outer membrane vesicles during colicin A secretion, as has been hypothesized (14, 46). It is more pronounced in cells grown in M9 medium than in cells grown in LB medium, perhaps due to the high concentration of divalent cations present in minimal medium, which are known to stabilize vesicles.

The colicin A associated with OMPLA could play a role in secretion. It could constitute a channel in the outer membrane through which the cytoplasmic colicin might transit during release into the medium with the help of Cal. This would explain why colicin release does not occur in mutants with an inactive OMPLA (41). All the protein secretion process described in gram-negative bacteria involve an oligomeric outer membrane protein which forms a pore used to transport proteins across the outer membrane (16, 26, 27, 35). In type II and III secretion systems, this multimeric protein is called secretin and is often associated with a secretin-specific pilot protein that is a lipoprotein (5). Colicins Au are not multimeric, and Cal, which is a lipopeptide synthesized with colicin A, did not appear to pilot them to the outer membrane.

In type I secretion system, the last step of protein release requires an outer membrane protein, TolC, which is formed by a β-barrel fused to a long α-helical tunnel (32). The complex OMPLA-colicin A could form a structural homologue to that of TolC. The β-barrel of OMPLA contains 12 β-strands and spans the outer membrane, as does the β-barrel of TolC (45). By interacting with OMPLA via its α-helical C-terminal domain, colicin Au could form an α-helical tunnel extending from the inner side of the outer membrane to the periplasmic space similar to the α-helical barrel of TolC, which protrudes far into the periplasm. This location could explain the partial sensitivity to trypsin of colicins Au in isolated outer membrane fractions (not shown). Colicin A export could take place with the help of Cal through the composite tunnel formed by association of colicin Au and OMPLA.

However, colicin lysis proteins do not require colicin to provoke protein release (14, 46). Furthermore, colicin X345, which gives heat-labile forms, is not secreted (1) while colicin BC7, which does not produce them, is secreted as well as wild-type colicin A (2). But the structure of these two constructed colicin A derivatives differs significantly from that of the wild type. Colicin X345 aggregates spontaneously and might be unable to be released. Colicin BC7 contains only the N-terminal domain of colicin A and might be released by Cal by an alternative means.

Colicins Au seemed to play a role in regulating expression of the colicin operon. The expression of colicin A was reduced in ompF 9301 cells, which lack OmpF and contain OmpC, but was not reduced in B cells, which lack OmpC, or in BZB1107 cells, which lack both porins. That suggested a negative role of OmpC on colicin A production. In contrast, OMPLA appeared to play a positive role in colicin A induction, as no colicin A was produced in cells devoid of OMPLA. Its role in colicin E1 expression also seemed very significant, as colicin E1 was not produced in W3110 pldA cells, which contain an inactive OMPLA (data not shown).

Colicin A is a polymorphic protein. It requires changes of conformation in order to be released and to carry out its lethal activity. Characterization of its various forms and isolation of mutants devoid of specific forms would help to understand colicin A release and functioning at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

I thank Richard James, Stephen Slatin, and James Sturgis for critical reading of the manuscript. I am grateful to Jean-Claude Lazzaronni, Roland Lloubès, and the late Hubertus M. Verheij for the gift of strains, to Roland Lloubès and Jean-Marie Pagès for the gift of polyclonal antibodies to OmpF, to Jan Tommassen for the gift of polyclonal antibodies against phospholipase A, and to Niek Dekker and Roelie Kingma for the gift of monoclonal antibodies against phospholipase A.

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baty, D., M. Knibiehler, H. Verheij, F. Pattus, D. Shire, A. Bernadac, and C. Lazdunski. 1987. Site-directed mutagenesis of the COOH-terminal region of colicin A: effect on secretion and voltage-dependent channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:1152-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baty, D., R. Lloubès, V. Géli, C. Lazdunski, and P. S. Howard. 1987. Extracellular release of colicin A is non-specific. EMBO J. 6:2463-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedetti, H., M. Frenette, D. Baty, M. Knibielher, F. Pattus, and C. Lazdunski. 1991. Individual domains of colicins confer specificity in colicin uptake, in pore-properties and in immunity requirement. J. Mol. Biol. 217:429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein, H. D. 2000. The biogenesis and assembly of bacterial membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitter, W., and J. Tommassen. 1999. Ushers and other doorkeepers. Trends Microbiol. 7:4-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolla, J. M., C. Lazdunski, and J. M. Pagès. 1988. The assembly of the major outer membrane protein OmpF of Escherichia coli depends on lipid synthesis. EMBO J. 7:3595-3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brock, R. G. P., E. Brinkman, R. van Boxtel, A. C. P. A. Bekkers, H. Verheij, and J. Tommassen. 1994. Molecular characterization of enterobacterial pldA genes encoding outer membrane phospholipase A. J. Bacteriol. 176:861-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cascales, E., A. Bernadac, M. Gavioli, J. C. Lazzaroni, and R. Lloubès. 2002. Pal lipoprotein plays a major role for outer membrane integrity. J. Bacteriol. 184:754-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavard, D. 1991. Synthesis and functioning of the colicin E1 lysis protein: comparison with the colicin A lysis protein. J. Bacteriol. 173:191-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavard, D. 1998. Inhibition of colicin synthesis by the antibiotic globomycin. Arch. Microbiol. 171:50-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavard, D., D. Baty, S. P. Howard, H. Verheij, and C. Lazdunski. 1987. Lipoprotein nature of the colicin A lysis protein: effect of amino acid substitutions at the site of modification and processing. J. Bacteriol. 169:2187-2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavard, D., A. Bernadac, and C. Lazdunski. 1981. Exclusive localization of colicin A in cell cytoplasm of producing bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 119:125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavard, D., and C. Lazdunski. 1981. Involvement of BtuB and OmpF proteins in binding and uptake of colicin A. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 12:311-316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavard, D., and B. Oudega. 1992. General introduction to the secretion of bacteriocins, p. 297-305. In R. James, C. Lazdunski, and F. Pattus (ed.), Bacteriocins, microcins and lantibiotics, vol. H65. NATO ASI Series, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 15.Chai, T. J., and J. Foulds. 1977. Escherichia coli K-12 tolF mutants: alterations in protein composition of the outer membrane. J. Bacteriol. 130:781-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crago, A. M., and V. Koronakis. 1998. Salmonella InvG forms a ring-like multimer that requires the InvH lipoprotein for outer membrane localization. Mol. Microbiol. 30:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daefler, S., and M. Russel. 1998. The Salmonella typhimurium InvH protein is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for the proper localization of InvG. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1367-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danese, P. N., and T. Silhavy. 1999. Targeting and assembly of periplasmic and outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32:59-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis, N. G., and P. Model. 1985. An artificial anchor domain: hydrophobicity suffices to stop transfer. Cell 41:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dekker, N., J. Tommassen, A. Lustig, J. P. Rosenbusch, and H. M. Verheij. 1997. Dimerization regulates the enzymatic activity of outer membrane phospholipase A. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3179-3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekker, N., J. Tommassen, and H. M. Verheij. 1999. Bacteriocin release protein triggers dimerization of outer membrane phospholipase A in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 181:3281-3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derouiche, R., M. Gavioli, H. Bénédetti, A. Prilipov, C. Lazdunski, and R. Lloubès. 1996. TolA central domain interacts with Escherichia coli porins. EMBO J. 15:6408-6415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freudl, R., H. Schwarz, Y. D. Stierhof, K. Gamon, I. Hindennach, and U. Henning. 1986. An outer membrane protein (OmpA) of Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes a conformational change during export. J. Biol. Chem. 261:11355-11361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Géli, V., R. Lloubès, S. A. J. Zaat, R. M. L. van Spaendonk, C. Rollin, H. Benedetti, and C. Lazdunski. 1993. Recognition of the colicin A N-terminal epitope 1C11 in-vitro and in-vivo in Escherichia coli by its cognate monoclonal antibody. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 109:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Manas, J. M., J. H. Lakey, and F. Pattus. 1993. Interaction of the colicin A pore-forming domain with negatively charged phospholipids. Eur. J. Biochem. 211:625-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardie, K. R., S. Lory, and A. P. Pugsley. 1996. Insertion of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli requires a chaperone-like protein. EMBO J. 15:978-988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson, I. R., R. Cappello, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Autotransporter proteins, evolution and redefining protein secretion. Trends Microbiol. 8:529-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard, S. P., D. Cavard, and C. Lazdunski. 1991. Phospholipase-A-independent damage caused by the colicin A lysis protein during its assembly into the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:81-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen, C., M. Heutink, J. Tommassen, and H. de Cock. 2000. The assembly pathway of outer membrane protein PhoE of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3792-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim, Y., K. Valentine, S. J. Opella, S. L. Schendel, and W. A. Cramer. 1998. Solid-state NMR studies of the membrane-bound closed state of the colicin E1 channel domain in lipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 7:342-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knibiehler, M., and C. Lazdunski. 1987. Conformation of colicin A: apparent difference between cytoplasmic and extracellular polypeptide chain. FEBS Lett. 216:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koronakis, V., A. Sharff, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakey, J. H., J. M. Gonzalez-Manas, F. G. van der Goot, and F. Pattus. 1992. The membrane insertion of colicins. FEBS Lett. 307:26-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langen, G. R., J. R. Harper, T. Silhavy, and S. P. Howard. 2001. Absence of the outer membrane phospholipase A suppresses the temperature-sensitive phenotype of Escherichia coli degP mutants and induces the Cpx and σE extracytoplasmic stress responses. J. Bacteriol. 183:5230-5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Létoffé, S., P. Delepelaire, and C. Wandersman. 1996. Protein secretion in Gram-negative bacteria: assembly of the three components of ABC protein-mediated exporters is ordered and promoted by substrate binding. EMBO J. 15:5804-5811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacIntyre, S., R. Freudl, M. L. Eschbach, and U. Henning. 1988. An artificial hydrophobic sequence functions as either an anchor or signal sequence at only one of two positions within the Escherichia coli outer membrane protein OmpA. J. Biol. Chem. 263:19053-19059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura, K., and S. Mizushima. 1976. Effects of heating in dodecyl sulfate solution on the conformation and electrophoretic mobility of isolated major outer membrane proteins from Escherichia coli K12. J. Biochem. 80:1411-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osborn, M. J., J. E. Gander, E. Parisi, and J. Carson. 1972. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 247:3962-3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oudega, B., F. Stegehuis, G. J. van Tiel-Menkveld, F. K. de Graaf. 1982. Protein H encoded by plasmid CloDF13 is involved in excretion of cloacin DF13. J. Bacteriol. 150:1115-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker, M. W., F. Pattus, A. D. Tucker, and D. Tsernoglou. 1989. Structure of the membrane-pore-forming fragment of colicin A. Nature 337:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pugsley, A. P., and M. Schwartz. 1984. Colicin E2 release: lysis, leakage or secretion? Possible role of a phospholipase. EMBO J. 3:2393-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenbusch, J. P. 1974. Characterization of the major envelope protein from Escherichia coli. Regular arrangement on the peptidoglycan and unusual dodecyl sulfate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 249:8019-8029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scandella, C. J., and A. Kornberg. 1971. A membrane-bound phospholipase A1 purified from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 10:4447-4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slatin, S. L., X. Q. Qiu, K. S. Jakes, and A. Finkelstein. 1994. Identification of a translocated protein segment in a voltage-dependent channel. Nature 371:158-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snijder, H. J., I. Ubarretxena-Bellandia, M. Blaauw, K. H. Kalk, H. M. Verheij, M. R. Egmond, N. Dekker, and B. W. Djikstra. 1999. Structural evidence for dimerization-regulated activation of an integral membrane phospholipase. Nature 401:717-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Wal, F., J. Luirink, and B. Oudega. 1995. Bacteriocin release proteins: mode of action, structure and biotechnological application. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 17:381-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vetter, I. R., M. W. Parker, A. D. Tucker, J. H. Lakey, F. Pattus, and D. Tsernoglou. 1998. Crystal structure of a colicin N fragment suggests a model for toxicity. Structure 6:863-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiener, M., D. Freymann, P. Ghosh, and R. M. Stroud. 1997. Crystal structure of colicin. Nature 385:461-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]