Abstract

Mutations A49P and Δ47-53 at the T loop of the Escherichia coli GlnB (PII) protein impair regulatory interactions with the two-component sensor regulator NtrB (P. Jiang, P. Zucker, M. R. Atkinson, E. S. Kamberov, W. Tirasophon, P. Chandran, B. R. Schepke, and A. J. Ninfa, J. Bacteriol. 179: 4342-4353, 1997). We show here that these mutations also impair interactions between PII and NtrB in the yeast two-hybrid system, indicating that defects in NtrB regulation closely reflect binding impairment. The reported results underline the strength of two-hybrid assays for analysis of interactions involving the T loop of PII proteins.

PII proteins play a key role in both transcriptional regulation and metabolic regulation in bacteria, being among the most ubiquitous signal transduction proteins (reviewed in reference 1). Two paralogous genes, glnB and the more recently discovered gene glnK, encode PII proteins (referred to as GlnB and GlnK, respectively) in enterobacteria. The physical properties of the Escherichia coli GlnB and GlnK proteins are very similar, and under some circumstances, GlnK can substitute for GlnB. The structures of the E. coli PII proteins are known to high resolution (16, 17).

GlnB is involved in nitrogen status signaling to glutamine synthetase (GS), the key enzyme for the assimilation of ammonia. This is performed by regulating both the activity of GS by reversible adenylylation and the transcription of glnA, which encodes GS. The nitrogen status of the cell is sensed by the uridylyltranferase/uridylyl-removing (UTase/UR) enzyme encoded by glnD (12). The UTase/UR enzyme uridylylates GlnB at Tyr51 to form GlnB-UMP under nitrogen limitation conditions and deuridylylates it under nitrogen excess conditions (1). Nonuridylylated GlnB activates the adenylylation activity of the bifunctional GS adenylyl-transferase (ATase) and weakly inhibits its deadenylylation activity, while GlnB-UMP activates the deadenylylation activity of the ATase. Nonuridylylated GlnB interacts with NtrB to determine the balance of the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation reactions of NtrB (7, 8, 13) which, in turn, catalyzes the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of NtrC, the transcriptional regulator of the ntr regulon. NtrB and NtrC are the sensor and response regulator, respectively, of a two-component signal transduction system based on histidine-aspartate phosphotransfer (reviewed in reference 15). Therefore, interaction of GlnB with three different bifunctional signal-transducing enzymes (UTase/UR, ATase, and NtrB) is at the center of nitrogen signal transduction.

The key issue of specificity of interactions of PII proteins with their protein receptors has already been addressed for GlnB, where mutational analysis indicates that functional interactions with its three known receptors map to the T loop and are genetically separable (9). Two types of GlnB mutants (also referred to as PII here) affecting interactions with NtrB were reported in that work: (i) those affected in interactions with all three receptors and (ii) those with the A49P mutation, which are unable to elicit NtrB phosphatase activity but interact normally with the UTase/UR and ATase enzymes. Unanswered by that study was the question of whether defects in eliciting the measured activities of the receptors reflect defects in binding.

In a previous work, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to probe interactions between NtrB and GlnB from Klebsiella pneumoniae, showing that GlnB specifically contacts the transmitter module of NtrB (11), a result in close agreement with in vitro cross-linking between GlnB and the C-terminal domain of NtrB (13). Here we investigated the impact on two-hybrid signals of mutations impairing the ability of PII to regulate NtrB phosphatase. To this end, we used two different types of E. coli PII derivatives: PIIΔ47-53, in which the apex of the T loop is deleted and which is completely defective in interactions with all three receptors, and PIIA49P, which has a point mutation in the T loop that specifically abolishes NtrB regulation. The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. To construct two-hybrid plasmids pUAG173 and pUAG174, pJLA503A49P was digested with NdeI, Klenow treated, and cut with BamHI and the corresponding 490-bp fragment was cloned into pGAD424 and pGBT9, respectively. Plasmid pJLA503Δ47-53 was cut with NdeI, Klenow treated, and cut with BamHI, and the corresponding 469-bp fragment was cloned into pGBT9, giving plasmid pUAG176. An EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pUAG176 was cloned into pGAD424, giving plasmid pUAG175.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80d lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 λ− | 5 |

| S. cerevisiae Y190 | MATa ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 trp1-90 leu2-3, 112 gal4Δ gal80Δ URA3::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-lacZ LYS2::GAL1UAS-HIS3TATA-HIS3 cyhr2 | 6 |

| pGAD424 | AmprLEU2 GAL4(768-881)AD | 3 |

| pGBT9 | AmprTRP1 GAL4(1-147)BD | 4 |

| pJAL503-PIIA49P | glnB T-loop point mutation | 9 |

| pJAL503-PIIΔ47-53 | glnB T-loop deletion mutation | 9 |

| pUAG211 | GAL4AD-NtrB | 11 |

| pUAG212 | GAL4BD-NtrB | 11 |

| pUAG221 | GAL4AD-NtrBHNG | 11 |

| pUAG222 | GAL4BD-NtrBHNG | 11 |

| pUAG171 | GAL4AD-PII | 11 |

| pUAG172 | GAL4BD-PII | 14 |

| pUAG173 | GAL4AD-PIIA49P | This work |

| pUAG174 | GAL4BD-PIIA49P | This work |

| pUAG175 | GAL4AD-PIIΔ47-53 | This work |

| pUAG176 | GAL4BD-PIIΔ47-53 | This work |

Fusion proteins consisted of the activator or DNA-binding domain of GAL4 (GAL4AD and GAL4BD) fused to the N termini of the corresponding polypeptides. To determine the ability of two given polypeptides to interact in the two-hybrid system, expression of both GAL1::lacZ and GAL1::HIS3 reporters was analyzed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y190 by β-galactosidase assay and growth on histidine-deficient medium, respectively. S. cerevisiae Y190 was cotransformed with different pairs of two-hybrid plasmids (1 μg of each), and at least four independent clones were selected for further analysis. The yeast culture and transformation procedures used were as previously described (2). β-Galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (14). Growth on histidine-deficient medium was analyzed on solid YNB medium lacking His, Leu, and Trp in the presence of different concentrations of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole, and growth rates were categorized into four classes (++, +, ±, and −) as previously described (10). The fusion proteins carried by a given strain are always named in the order GAL4AD-X/GAL4BD-Y, which is abbreviated X/Y, where X or Y is any polypeptide fused to GAL4AD and GAL4BD, respectively. Following previously established conventions, the transmitter module of NtrB is designated NtrBHNG. For simplicity, GlnB derivatives are designated PII here.

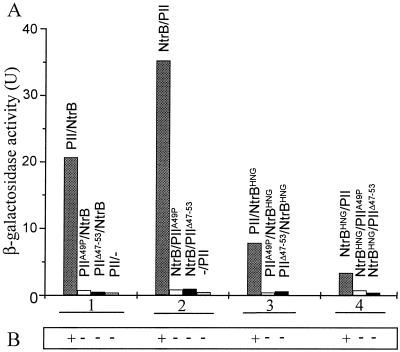

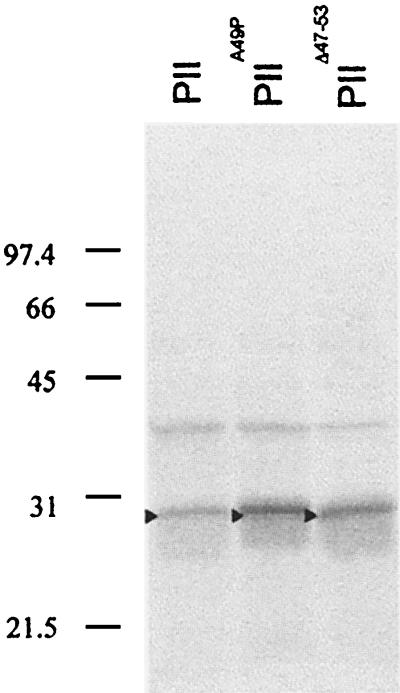

When mutant and wild-type versions of PII were tested for the ability to interact with NtrB or NtrBHNG, both PIIΔ47-53 and PIIA49P failed to give signals with the two reporter genes while significant signals were always obtained with PII (Fig. 1). GlnB wild-type fusion proteins from both K. pneumoniae and E. coli were assayed with identical results (data not shown). Therefore, these results closely parallel the failure of the corresponding mutant PII proteins to regulate NtrB both in vivo and in vitro (9). To exclude a negative impact of the T-loop mutations on the stability of fusion proteins in yeast, their expression was analyzed by Western blot assays. As shown in Fig. 2, expression of mutant PII derivatives in yeast is as good as that of their wild-type counterpart, thus indicating that the lack of interaction in the two-hybrid system observed with PIIΔ47-53 and PIIA49P is not due to reduced stability of the corresponding fusion proteins in the yeast system and suggesting that the inability of the corresponding mutant proteins to elicit NtrB phosphatase activity does, indeed, reflect binding impairment. The fact that PIIA49P specifically and completely abolished interaction with NtrB and NtrBHNG in the two-hybrid system suggests either that there are no additional determinants outside the T loop or that they are not important enough to overcome the deleterious effect of the A49P change on NtrB recognition.

FIG. 1.

Effects of PII T-loop mutations on expression of GAL1::lacZ and GAL1::HIS3 in strain Y190 carrying different pairs of fusion proteins. Dashes indicate the absence of proteins fused to GAL4 domains. The numbered lines between panels A and B encompass blocks of data according to the type of comparison: 1, PII derivatives paired with GAL4BD-NtrB; 2, PII derivatives paired with GAL4AD-NtrB; 3, PII derivatives paired with GAL4BD::NtrBHNG; 4, PII derivatives paired with GAL4AD-NtrBHNG. (A) Each bar represents the mean β-galactosidase activity of at least four independent transformants, each measured in triplicate. (B) Levels of growth on histidine-deficient medium.

FIG. 2.

Western blotting of GAL4BD fused to PII and mutant derivatives. In each case, protein extracts were derived from 2- to 3-ml cultures (turbidity at 600 nm, 2) of Y190 also carrying GAL4AD-NtrB. Protein extracts were treated, separated, transferred to the membrane, and probed with a monoclonal antibody to GAL4BD (sc-510) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology as previously described (11). An arrowhead points to the protein indicated above each lane. The values to the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of protein size standards.

It is worth noting that, with the exception of its ability to regulate NtrB, the A49P point mutation does not affect any known property or function of PII. In fact, and in spite of the close proximity of Ala49 to Tyr51, the active site for the uridylyl transfer reaction, PIIA49P is uridylylated as efficiently as PII (9). The specific impact of the A49P point mutation on interactions with NtrB is also observed in the yeast two-hybrid system, since UTase/PII and UTase/PIIA49P, but not UTase/PIIΔ47-53, gave signals with both the GAL1::lacZ and GAL1::HIS3 reporters (data not shown).

In addition to establishing, for particular PII mutants, a clear correlation between regulation of NtrB and the ability to interact in the two-hybrid system, our results indicate that the yeast two-hybrid system used here may be particularly fruitful when used to study interactions mediated by T-loop-containing proteins such as PII, further validating the use of yeast two-hybrid approaches to address two different biological problems: the study of specific interactions with known PII receptors by direct and reverse strategies and the identification of additional receptors for PII proteins. Given the growing interest in the function of PII proteins from a great variety of organisms, for the majority of which there are no genetic tools available, it can be anticipated that the use of PII as bait to screen genomic libraries would greatly facilitate the task of identifying PII receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant PB97-0115 from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

We thank I. Fuentes for excellent technical assistance, R. Maldonado and A. Ninfa for providing plasmids, and A. Ninfa for encouragement of this work and comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcondeguy, T., R. Jack, and M. Merrick. 2001. P(II) signal transduction proteins, pivotal players in microbial nitrogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:80-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1999. Short protocols in molecular biology, 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bartel, P., C. T. Chien, R. Sternglanz, and S. Fields. 1993. Elimination of false positives that arise in using the two-hybrid system. BioTechniques 14:920-924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien, C. T., P. L. Bartel, R. Sternglanz, and S. Fields. 1991. The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9578-9582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan, D. 1985. Techniques for transformation of Escherichia coli, p. 109-135. In D. Glover (ed.), DNA cloning. IRL Press Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 6.Harper, J. W., G. R. Adami, N. Wei, K. Keyomarsi, and S. J. Elledge. 1993. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75:805-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang, P., M. R. Atkinson, C. Srisawat, Q. Sun, and A. J. Ninfa. 2000. Functional dissection of the dimerization and enzymatic activities of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II and their regulation by the PII protein. Biochemistry 39:13433-13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang, P., and A. J. Ninfa. 1999. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:1906-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang, P., P. Zucker, M. R. Atkinson, E. S. Kamberov, W. Tirasophon, P. Chandran, B. R. Schepke, and A. J. Ninfa. 1997. Structure/function analysis of the PII signal transduction protein of Escherichia coli: genetic separation of interactions with protein receptors: J. Bacteriol. 179:4342-4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Argudo, I., J. Martín-Nieto, P. Salinas, R. Maldonado, M. Drummond, and A. Contreras. 2001. Two-hybrid analysis of domain interactions involving NtrB and NtrC two-component regulators. Mol. Microbiol 40:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Argudo, I., P. Salinas, R. Maldonado, and A. Contreras. 2002. Domain interactions on the ntr signal transduction pathway: two-hybrid analysis of mutant and truncated derivatives of histidine kinase NtrB. J. Bacteriol. 184:200-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merrick, M. J., and R. A. Edwards. 1995. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:604-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pioszak, A. A., P. Jiang, and A. J. Ninfa. 2000. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein regulates the activities of the two-component system transmitter protein NRII by direct interaction with the kinase domain of the transmitter module. Biochemistry 39:13450-13461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider, S., M. Buchert, and C. M. Hovens. 1996. An in vitro assay of beta-galactosidase from yeast. BioTechniques 20:960-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West, A. H., and A. M. Stock. 2001. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:369-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu, Y., E. Cheah, P. D. Carr, W. C. van Heeswijk, H. V. Westerhoff, S. G. Vasudevan, and D. L. Ollis. 1998. GlnK, a PII-homologue: structure reveals ATP binding site and indicates how the T-loops may be involved in molecular recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 282:149-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu, Q., P. D. Carr, T. Huber, S. G. Vasudevan, and D. L. Ollis. 2001. The structure of the PII-ATP complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:2028-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]