Abstract

Wing geometric morphometry was used to study the spatial structuring of populations of Triatoma infestans from different villages, ecotopes, and sites within a village in northwestern Argentina. A total of 308 male and 197 female wings of T. infestans collected from peridomestic and domestic ecotopes in March 2000 was analyzed. On average, female bugs had a significantly larger wing size than males. Triatomines collected from domiciles or structures associated with chickens had larger wings than bugs collected from goat or pig corrals. The wing size of bugs did not differ significantly between villages. Discriminant analyses of wing shape showed significant divergence between villages, ecotopes, and individual collection sites. The study of metric variation of males between sites belonging to the same ecotope also revealed significant heterogeneity. Indeed, within the same section of the village the difference between two goat corrals was sometimes greater than that between neighboring goat and pig corrals. Thus, morphometric heterogeneity within villages may be the result not only of ecotope and host associations, but also of physical isolation between subunits. The strong structuring of T. infestans populations in the study area indicates that recolonization could be traced back to a small geographic source.

Keywords: Triatoma infestans, geometric morphometry, population structure, isometric size, shape

Triatoma infestans (Klug) is the principal vector of Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas’ disease. T. infestans occurs almost exclusively in domestic or peridomestic habitats, with very rare sylvatic populations (Carcavallo et al. 1988, Dujardin et al. 1987). The transmission of T. cruzi to humans mostly occurs in human habitations (the domestic environment or domiciles) as a result of the interaction between domestic triatomines, infected dogs or cats, people, and chickens (Cohen and Gürtler 2001). The peridomestic rural environment usually includes a wide array of structures, such as goat, sheep, and pig corrals; chicken coops; and storerooms. In northern Argentina, these ecotopes are very frequently infested by T. infestans and other triatomine species (Cecere et al. 1997, 2002; Canale et al. 2000). Peridomestic sites were the most important source of T. infestans that reinvaded the house after residual spraying of insecticides, but at least in Argentina they were not a source of T. cruzi-infected bugs (Cecere et al. 1999, 2002).

Most morphometric studies on T. infestans have been based on traditional morphometry to compare insects grown under laboratory conditions or colonizing human dwellings and sylvatic habitats (Dujardin et al. 1997a, b). Triatomines collected from human dwellings tended to show a reduced size relative to sylvatic populations (Dujardin et al. 1997a, 1997b, 1998a, 1999; Schofield et al. 1999). None of these studies compared T. infestans from domestic and peridomestic ecotopes within and between villages from a well-defined area.

Traditional morphometry does not allow recovering the geometry of the original form from the usual distance measurements (Rohlf and Marcus 1993). In contrast, geometric morphometry preserves the information on spatial arrangement of the organism and reduces the effects of differences in growth, which generally have environmental causes. When growth effects are properly removed from shape and significant differences between groups are still detected, shape variables are supposed to reflect adaptive (or genetic) causes rather than mere environmental influences. Geometric morphometry has been applied to Triatominae for taxonomic purposes (Matias et al. 2001, Villegas et al. 2002); to distinguish laboratory-reared and field specimens (Jaramillo et al. 2002); and to assess the chromatic variation of T. infestans across several countries (Gumiel et al. 2003). As part of a broader project on the eco-epidemiology of Chagas’ disease in northern Argentina, we report in this work the first attempt to use geometric morphometry to study the spatial structuring of T. infestans populations at a finer geographic scale. The metric variation of wings was investigated within and between rural communities in a 10 km × 10 km area with documented control interventions.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Insects

The insects were captured in the rural villages of Amamá, Trinidad, Mercedes, and San Pablo (27.18° S, 63.08° W), Moreno Department, Province of Santiago del Estero, Argentina, in March 2000. The area and its history of infestation by T. infestans were described by Gürtler et al. (1994). Amamá had 88% of houses with bedroom areas infested by T. infestans before being sprayed with 2.5% suspension concentrate deltamethrin at 25 mg active ingredient/m2 by the National Chagas Service (NCS) in September 1985, and again in October 1992 (Gürtler et al. 1994, Cecere et al. 2002). Reinfested sites were selectively sprayed with deltamethrin by NCS (1993–1995) or householders themselves (since 1996). Other rural areas at the department level were first sprayed with residual insecticides against triatomine bugs in 1994–1995 and irregularly thereafter. Most domiciles had adobe walls and thatched roofs; peridomestic sites were those that did not share a roof with bedroom areas, such as storerooms and chicken coops (where chickens usually nested; both structures hereafter will be called chicken coops for convenience), corrals (goat and pig corrals), and wood piles.

Three skilled bug collectors from NCS searched for triatomines in all bedroom and peridomestic areas using 0.2% tetramethrin dislodgant (Icona, Buenos Aires, Argentina) in 117 houses that included 525 identified peridomestic sites from 14 to 27 March 2000. The bugs were identified to species and stage at the field laboratory, as described elsewhere (Canale et al. 2000), and stored at −20°C.

Metric Data

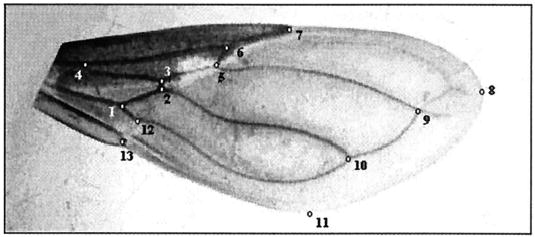

In total, 308 male and 197 female wings of T. infestans were examined (Table 1). The wings were mounted between microscope slides and cover-slips using a commercial adhesive. Photographs of each pair of wings were taken using a digital camera and a stereo-microscope. We identified a total of 11 type I landmarks (venation intersections) and two type II landmarks, according to Bookstein (1990) (Fig. 1). The geometric coordinates of each landmark were digitized using tpsDig version 1.18 (Rohlf 1999a).

Table 1.

Numbers (n) of male and female T. infestans wings examined for geometric morphometry according to site of capture

| Males (n = 308)

|

Females (n = 197)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | T | S | Total | A | M | T | S | Total | |

| Domiciles | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Chicken coops | 39 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 55 | 44 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 54 |

| Goat corrals | 59 | 0 | 36 | 12 | 107 | 20 | 8 | 18 | 8 | 54 |

| Pig corrals | 81 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 107 | 37 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 49 |

| Wood piles | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Total | 194 | 34 | 48 | 32 | 308 | 123 | 34 | 24 | 16 | 197 |

Amamá and nearby villages, March 2000: A, Amamá; M, Mercedes; T, Trinidad; S, San Pablo.

Fig. 1.

Points of reference measured as coordinates of wings of T. infestans. Numbering on the points denotes the arrangement followed to obtain the coordinates using tpsdig version 1.18. Points 8 and 11 correspond to landmarks type II, and the rest to landmarks type I.

Size Variation

For comparison of overall wing size between sexes and between ecotopes within each sex, we used the isometric estimator known as centroid size (CS) derived from coordinates data. CS is defined as the square root of the sum of the squared distances between the center of the configuration of landmarks and each individual landmark (Bookstein 1990). It was extracted from each matrix using tpsRegr version 1.18 (Rohlf 1999b).

Shape Variation

Shape variables (partial warps) were obtained using the Generalized Procrustes Analysis superimposition algorithm (Rohlf 1996). They were computed separately for each sex and tested for their variation using tpsRelw version 1.18 (Rohlf 1999c).

Statistical Analysis

We explored the variation of size, shape, or their combination at different spatial levels: 1) the village, 2) the ecotope, and 3) the individual site of insect collection. For the first two levels of comparison, the interaction with sex was first examined using either analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for size, which is a single variable) or multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) (for shape, which is a set of many variables). For the third level, such analyses could not be performed.

When possible, the problem of sample size lower than the number of shape variables (see discussion in Bookstein 1996) was circumvented by using a restricted representation of shape, i.e., a set of principal components (relative warps) derived from the shape variables. This procedure reduced the amount of captured shape, but the reduction never exceeded 10%. Because sample size for females did not reach the minimum number of wings required per individual site, analysis of shape variation at site level was performed on male insects only. The analysis compared 8 units across three villages: three goat and three pig corrals from Amamá, one goat corral from Trinidad, and one pig corral from San Pablo.

Mahalanobis distances were derived from these analyses, and their statistical significance was computed by nonparametric permutation tests (1000 runs each) after Bonferroni correction. These distances were used in an unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) cluster analysis to produce a dendrogram. Reclassification based on these distances was evaluated by the Kappa statistic (Fleiss 1981).

The software used was: BAC (version 23; http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/) for principal component analyses; PAD (version 40; http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/) for discriminant analyses and permutations; PHYLIP (version 3.5c.) and treeview (version 1.6.6.) for unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average tree construction; and JMP (version 3.2.2) for ANOVA on size and Kappa statistic.

Results

Size Variation

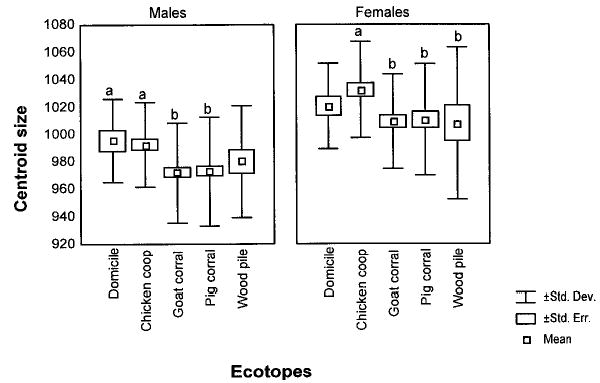

Female wing size (CSf = 1017.1, SD = 39.32) was significantly larger than male wing size (CSm = 977.3, SD = 38.98) (F = 66.35, df =1, P < 0.0001). Wing size significantly differed between ecotopes, but not between villages (F = 7.18, df = 4, P < 0.0001, and F =1.61, df = 3, P > 0.1, respectively), with no significant interaction effect of sex (F = 0.43, df = 4, P > 0.5, and F = 2.1, df = 3, P = 0.1, respectively). For each sex, triatomines collected from domiciles and chicken coops had larger wing size than those collected from goat or pig corrals and wood piles (Fig. 2). Statistically significant differences were observed between male bugs collected from domiciles or chicken coops and corrals, and between females collected from chicken coops and corrals or wood piles. The wing size of the T. infestans collected from goat and pig corrals did not differ significantly between villages.

Fig. 2.

Variation of CS between ecotopes and sex of T. infestans. Box plots show the isometric size differences of wings between ecotopes for each sex. Each box shows the mean, standard error, and standard deviation of each group. Asterisks followed by different letters showed statistically significant differences.

Shape Variation

Wing shape showed significant divergence between villages (P < 0.002) and ecotopes (P < 0.0001). Because of a highly significant interaction with sex at both subdivision levels, this divergence was examined by separate discriminant analyses in each sex. The last level of subdivision (the site of capture) was examined for males only, producing again a significant heterogeneity of size and shape.

The reclassification scores of the discriminant analysis were the lowest for the villages that had a wider range of ecotopes (Amamá and Trinidad for males, 64–65%; or Amamá and Mercedes for females, 55–59%) (Table 2). When size and shape variables were combined together to perform the discriminant analysis, the Kappa statistic was always improved (data not shown). Therefore, the rest of the analyses was performed by combining size and shape variables. The observed agreement between the observed and expected classification for bugs according to the village or ecotope where they had been captured was moderate (according to Landis and Koch 1977). The third level of comparisons (between physical sites of capture) gave the most satisfactory reclassification scores (Table 3).

Table 2.

Reclassification of samples of T. infestans according to sex and the village in which they had been captured, after a discriminant analysis using size and shape variables

| Males

|

Females

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | A | M | T | S | Observed total | Observed agreement | A | M | T | S | Observed total | Observed agreement |

| A | 124 | 16 | 32 | 22 | 194 | 64 | 68 | 13 | 25 | 17 | 123 | 55 |

| M | 1 | 28 | 5 | 0 | 34 | 82 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 3 | 34 | 59 |

| T | 10 | 5 | 31 | 2 | 48 | 65 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 24 | 75 |

| S | 2 | 2 | 1 | 27 | 32 | 84 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 16 | 94 |

| Total | 308 | 68 | 197 | 61 | ||||||||

A, Amamá; M, Mercedes; T, Trinidad; S, San Pablo.

Table 3.

Degree of correct classification among T. infestans bugs according to village, ecotope, and site of capture for both sexes

| Classification | Sex | Observed agreement | Kappa (standard error) |

|---|---|---|---|

| By village | Male | 68 | 0.51 (0.04) |

| Female | 61 | 0.43 (0.05) | |

| By ecotope | Male | 56 | 0.43 (0.04) |

| Female | 61 | 0.51 (0.04) | |

| By site of capture | Male | 72 | 0.68 (0.04) |

Observed agreement: proportion of individuals that have been correctly attributed to their respective group. Kappa: measure of agreement estimated between observed and expected classification scaled from 0 to 1, a score below 0 is considered poor; between 0.00 and 0.20, slight, between 0.21 and 0.40, fair; between 0.41 and 0.60, moderate; between 0.61 and 0.80, substantial; and between 0.81 and 1, perfect (Landis and Koch 1977).

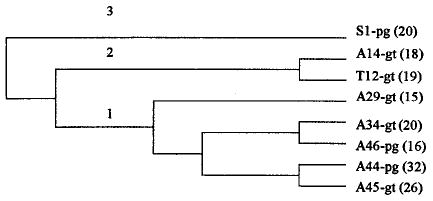

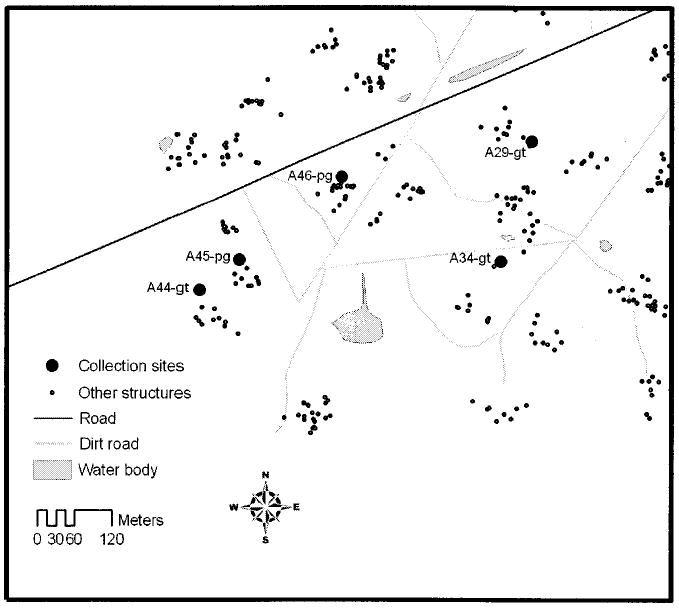

The results of the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average dendrogram (Fig. 3) showed that nearly all Amamá sites (group 1) were classified together as similar sites. These five sites were all located in the southwestern section of the village and within 200 m from each other (Fig. 4). However, one site from Amamá (A14) was grouped separately (group 2) with another site (T12) from Trinidad village, both being goat corrals (Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that site A14 was located >1.5 km northeast of the other Amamá sites (group 1) and separated from them by a canal.

Fig. 3.

Unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average dendrogram derived from Mahalonobis distances. A, Amamá; T, Trinidad; S, San Pablo; the number after the letter of the village is the house number; pg, pig corral; gt, goat corral; the number between parentheses is the sample size for each site.

Fig. 4.

Map of southeastern Amamá indicating the location of the collection sites in which bugs from group 1 of the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average dendrogram were collected.

Within group 1 (southwest Amamá), the similarity of wing shape from bugs in structures that were closest to each other was higher than from bugs from the same ecotope. Thus, bugs collected in goat corral A34 were grouped together with bugs collected from pig corral A46, and bugs collected in goat corral A45 were grouped together with bugs collected from pig corral A44 (Figs. 3 and 4).

Discussion

All species of Triatominae grown under controlled laboratory conditions or colonizing human dwellings tend to show a reduction in size relative to their sylvatic populations (Dujardin et al. 1997a, 1997b, 1998a, 1999; Jaramillo et al. 2002; Schofield et al. 1999). Natural selection may favor larger phenotypes in sylvatic habitats, possibly because of a greater capacity to resist temporary food shortages, while smaller individuals apparently survive better under laboratory or domestic conditions where food availability is less restricted (Dujardin et al. 1997a, 1997b). Dujardin et al. (1999) suggested that the morphological changes observed between sylvatic and laboratory populations within a given triatomine species might parallel those existing between sylvatic and domestic populations. Extrapolating to peridomestic versus domestic triatomines, we would expect to find bigger specimens in peridomestic rather than domestic ecotopes. However, triatomines collected from the more peridomestic goat corrals, pig corrals, or wood piles had smaller wing size than those collected from domestic sites or chicken coops. These differences may be explained by the poorer nutritional status and larger abundance of T. infestans in goat or pig corrals compared with bugs collected in structures in which chickens nested (unpublished data). Goat or pig corrals also experienced more marked variations in microsite temperature and relative humidity, which would affect growth rates (Vazquez-Prokopec et al. 2002). Host species effects may also be involved, because hosts may also differ in their nutritional characteristics (Guarneri et al. 2000). Experiments using the typical host species found in the field would help clarify whether there were any host species effects on wing shape and size.

An alternative, although not exclusive, explanation to size differences is associated with bug dispersal between ecotopes, resulting in triatomines captured in an ecotope in which they had not developed. Characteristics of these migrant bugs would be those that ensure success in dispersing to and colonizing the new site. Parallel studies on reinfestation dynamics in our study area suggested that such process was directional and progressed from peridomestic to domestic sites (Cecere et al. 1997, 2002). The higher local abundance and lower nutritional status of T. infestans from goat corrals suggested that adult triatomines from the latter would be more likely to disperse by flight than triatomines from chicken coops (unpublished data). Such selective dispersal would cause a decrease in mean bug size in goat corrals and an increase in storerooms, chicken coops, and domestic sites. Light trap collections revealed significant flight dispersal of T. infestans in summer (Vazquez-Prokopec et al. 2004).

The notable feature of morphometric variation disclosed by this study is the significant metric heterogeneity at a very fine spatial resolution, i.e., within villages and between unique sites of capture of insects such as individual (and neighboring) goat or pig corrals. The lower classification scores between villages or ecotopes versus individual sites of capture could indicate that villages or ecotopes were actually subdivided into discrete units, whereas the higher scores obtained for sites of capture suggested that they represented the discrete units in which metric differentiation took place.

The scores of village reclassification were the lowest for villages presenting a wider range of ecotopes (Amamá and Trinidad for males; Amamá and Mercedes for females) (Table 2). This is probably caused by the fact that bugs collected from different ecotopes varied significantly in size and shape; therefore, pooling different ecotopes into a single group (i.e., a village) could confound metric identification. However, the study of metric variation between sites belonging to the same ecotope also revealed significant heterogeneity. Indeed, the difference between two goat corrals was sometimes greater than between neighboring goat and pig corrals within the same section of the village. Distance per se, the canal or both could be acting as barriers to genetic flow between sites in the same village. This suggests that morphometric heterogeneity within villages may be related not only to ecotope and host associations, but also to some degree of physical isolation between subunits.

Our findings are in general agreement with other genetic studies. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis data have provided important information on gene flow and genetic structuring in domestic T. infestans populations. In Bolivia, the panmictic unit was suggested to be a group of villages separated by 50 km in Vallegrande, and single villages separated only by few kilometers in the Yungas valleys (Dujardin et al. 1988, 1998b). In other areas of Bolivia, however, the panmictic unit was represented by a single house or chicken coop when larger numbers of bugs were analyzed (Brenière et al. 1998). Such different levels of spatial structuring can be caused by several factors, such as topography, landcover, human-assisted passive dispersal, or active dispersal that may act as barriers or corridors between villages.

The fact that morphometric differences were detected between geographically close populations raises the question as to whether these differences were genetically determined or whether they were a consequence of sampling recently isolated triatomine populations affected by founder effects caused by community-wide residual insecticide sprays in 1992 and selective sprays carried out in 1995–1998. Our study does not address the origin of morphometric differences in T. infestans populations. Regardless of the underlying mechanisms of differentiation, the evidence points to a strong structuring of T. infestans populations. Microsatellite molecular markers are expected to give concluding evidence on the actual extent of spatial structuring.

The source of reinfestations has been generally difficult to determine, whether from local survivors of the initial treatment or immigrants from untreated, sylvatic foci (Dujardin et al. 1996, 1998b). Our data give confidence in the use of metric variation to tentatively identify the origin of reinfestation within a village, particularly when the comparisons involve contemporaneous generations of insects, or nearly so (all bugs used in this analysis were collected within a 2-wk period). Under these circumstances, the use of size in combination with shape may improve the reclassification.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Elisa Angrisano, Ellen Dotson, Carla Cecere, and the European Community–Latin American Network for Research on the Biology and Control of Triatominae (ECLAT) network for support. This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant R01 TW05836 funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to U. K. and R.E.G., and by grants from the University of Buenos Aires and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica (Argentina) to R.E.G. J.S.-B. was supported by a scholarship from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de Argentina (CONICET). R.E.G. is member of CONICET Researcher’s Career.

References

- Bookstein, F. L. 1990. Introduction to methods for landmark data, pp 216–225. In F. J. Rohlf and F. L. Bookstein (eds.), Proceedings, Michigan Morphometrics Workshop, 1988. The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Special Publication No. 2, Ann Arbor, MI.

- Bookstein, F. L. 1996. Combining the tools of geometric morphometrics: advances in morphometrics, pp. 131–152. In L. F. Marcus, M. Corti, A. Loy, G.J.P. Naylor, and D. Slice (eds.), Advances in morphometrics NATO ASI, series A, life sciences. Plenum Publication, New York.

- Brenière SF, Bosseno MF, Vargas F, Yaksic N, Noireau F, Noel S, Dujardin JP, Tibayrenc M. Smallness of the panmictic unit of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) J Med Entomol. 1998;35:911–917. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale DM, Cecere MC, Chuit R, Gürtler RE. Peridomestic distribution of Triatoma garciabesi and Triatoma guasayana in north-west Argentina. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:383–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcavallo RU, Canale DM, Martínez A. Habitats de triatominos argentinos y zonas ecológicas donde prevalecen. Chagas. 1988;5:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cecere MC, Gürtler RE, Canale D, Chuit R, Cohen JE. The role of the peridomiciliary area in the elimination of Triatoma infestans from rural Argentine communities. Pan Am J Public Health. 1997;1:273–279. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891997000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecere MC, Castañera MB, Canale DM, Chuit R, Gürtler RE. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in Triatoma infestans and other triatomines: long-term effects of a control program in rural northwestern Argentina. Pan Am J Public Health. 1999;5:392–399. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891999000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecere MC, Gürtler RE, Canale D, Chuit R, Cohen JE. Effects of partial housing improvement and insecticide spraying on the reinfestation dynamics of Triatoma infestans in rural northwestern Argentina. Acta Trop. 2002;84:101–16. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JE, Gürtler RE. Modeling household transmission of American trypanosomiasis. Science. 2001;293:694–698. doi: 10.1126/science.1060638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Tibayrenc M, Venegas E, Maldonado L, Desjeux P, Ayala FJ. Isozyme evidence of lack of speciation between wild and domestic Triatoma infestans (Heteroptera: Reduviidae) in Bolivia. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:40–45. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, La Fuente C, Cardozo L, Tibayrenc M. Dispersing behaviour of Triatoma infestans: evidence from a genetical study of field populations in Bolivia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1988;88:235–240. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761988000500042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Cardozo L, Schofield C. Genetic analysis of Triatoma infestans following insecticidal control interventions in central Bolivia. Acta Trop. 1996;61:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(96)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Bermúdez H, Schofield CJ. The use of morphometrics in entomological surveillance of sylvatic foci of Triatomainfestansin Bolivia. Acta Trop. 1997a;66:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Bermúdez H, Casini C, Schofield CJ, Tibayrenc M. Metric differences between sylvatic and domestic Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Bolivia. J Med Entomol. 1997b;34:544–551. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Forgues G, Torres M, Martinez E, Cordoba C, Gianella A. Morphometrics of domestic Pastrongylus rufotuberculaus in Bolivia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998a;92:219–228. doi: 10.1080/00034989860076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Schofield CJ, Tibayrenc M. Population structure of Andean Triatoma infestans: allozyme frequencies and their epidemiological relevance. Med Vet Entomol. 1998b;12:20–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1998.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Steindel M, Chávez T, Ponce C, Moreno J, Schofield CJ. Changes in the sexual dimorphism of Triatominae in the transition from natural to artificial habitats. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:565–569. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J. L. 1981. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, 3rd ed. Wiley, New York.

- Guarneri AA, Pereira MH, Diotaiuti L. Influence of the blood meal source on the development of Triatoma infestans, Triatoma brasiliensis, Triatoma sordida, and Triatoma pseudomaculata (Heteroptera: Reduviidae) J Med Entomol. 2000;37:373–379. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/37.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumiel M, Catalá S, Noireau F, RojasdeArias A, García A, Dujardin JP. Wing geometry in Triatoma infestans (Klug) and T. melanosoma Martinez, Olmedo & Carcavallo (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Syst Entomol. 2003;28:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gürtler RE, Petersen RM, Cecere MC, Schweigmann NJ, Chuit R, Gualtieri JM, Wisnivesky-Colli MC. Chagas’ disease in north-west Argentina: risk of domestic reinfestation by Triatoma infestans after a single community-wide application of deltamethrin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:27–30. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo N, Castillo D, Wolff ME. Geometric morphometric differences between Panstrongylus geniculatus from field and laboratory. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:667–673. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurements of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias A, de la Riva JX, Torrez M, Dujardin JP. Rhodnius robustus in Bolivia identified by wings. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:947–950. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F. J. 1996. Morphometric spaces, shape components and the effects of linear transformations, pp. 117–129. In L. F. Marcus, M. Corti, A. Loy, G.J.P. Naylor, and D. Slice (eds.), Advances in morphometrics NATO ASI, series A, life sciences. Plenum Publication, New York.

- Rohlf, F. J. 1999a. TPSDIG, version 1.18. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/).

- Rohlf, F. J. 1999b. TPSREGR, version 1.18. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/).

- Rohlf, F. J. 1999c. TPSRELW, version 1.18. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/).

- Rohlf FJ, Marcus LF. A revolution in morphometrics. Trends Ecol Evol. 1993;8:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90024-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield CJ, Diotaiuti L, Dujardin JP. The process of domestication in Triatominae. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:375–375. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000700073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Ceballos LA, Cecere MC, Gürtler RE. Seasonal variations of micro-climatic conditions in domestic and peridomestic habitats of Triatoma infestans in rural northwest Argentina. Acta Trop. 2002;84:229–238. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Ceballos LA, Kitron U, Gürtler RE. Active dispersal of natural populations of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in rural northwestern Argentina. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:614–621. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas J, Feliciangeli MD, Dujardin JP. Wing shape divergence between Rhodnius prolixus from Cojedes (Venezuela) and Rhodnius robustus from Mérida (Venezuela) Infect Genet Evol. 2002;2:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]