Abstract

An adenylyl cyclase gene (cyaA) present upstream of an osmosensor protein gene (mokA) was isolated from Myxococcus xanthus. cyaA encoded a polypeptide of 843 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 91,187 Da. The predicted cyaA gene product had structural similarity to the receptor-type adenylyl cyclases that are composed of an amino-terminal sensor domain and a carboxy-terminal catalytic domain of adenylyl cyclase. In reverse transcriptase PCR experiments, the transcript of the cyaA gene was detected mainly during development and spore germination. A cyaA mutant, generated by gene disruption, showed normal growth, development, and germination. However, a cyaA mutant placed under conditions of ionic (NaCl) or nonionic (sucrose) osmostress exhibited a marked reduction in spore formation and spore germination. When wild-type and cyaA mutant cells at developmental stages were stimulated with 0.2 M NaCl or sucrose, the mutant cells increased cyclic AMP accumulation at levels similar to those of the wild-type cells. In contrast, the mutant cells during spore germination had mainly lost the ability to respond to high-ionic osmolarity. In vegetative cells, the cyaA mutant responded normally to osmotic stress. These results suggested that M. xanthus CyaA functions mainly as an ionic osmosensor during spore germination and that CyaA is also required for osmotic tolerance in fruiting formation and sporulation.

Myxococcus xanthus is a gram-negative bacterium which migrates on semisolid surfaces by gliding. M. xanthus lives in the soil, where it moves in a social unit called a swarm and feeds on other bacteria. Under certain nutritionally limiting conditions, the vegetative cells undergo a developmental cycle involving cell-cell interactions. More than 105 cells migrate to an aggregation center and form a fruiting body, within which cells differentiate into myxospores. Since M. xanthus demonstrates complex social behavior, signal transduction systems in this bacterium have been studied widely (19, 24).

The environmental changes are transmitted to the cell by signal-transducing proteins. Cyclic AMP (cAMP) is one of the most common signaling molecules and is widely distributed from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. In mammalian cells, cAMP has significant roles in a variety of fundamental physiological regulatory mechanisms, e.g., cell differentiation, transcriptional regulation, and myocardial contraction. In the prokaryotes and in eukaryotic microorganisms, intracellular cAMP levels change in response to changes in environmental conditions. In Escherichia coli, there is an apparent interaction between concentrations of cAMP in cells and those of glucose in medium, and cAMP receptor protein-cAMP complex is essential for transcription of the glucose permease gene (20). Under conditions of nitrogen starvation, the pseudohyphal growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by cAMP signal transduction pathways (3). Upon nutrient starvation, the eukaryotic slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum undergoes a spectacular development cycle, in which extracellular cAMP acts as a chemoattractant controlling cell aggregation and also induces the differentiation of spore cells (14). In this organism, spore germination is also controlled by cAMP signal transduction pathways (10, 33).

The synthesis of cAMP is catalyzed by the enzyme adenylyl cyclase, and the adenylyl cyclases are found in all animals, plants, and bacteria. There are at least nine closely related isoforms of adenylyl cyclases for which the genes have been cloned and characterized in mammals (9). These adenylyl cyclases are membrane proteins of more than 1,000 amino acids that commonly have two sets of six transmembrane spans and two sets of conserved catalytic domains. E. coli and some eubacteria have hydrophilic adenylyl cyclases, which possess an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal regulatory domain (1). There is no sequence similarity between these proteins and mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Receptor-type adenylyl cyclases are composed of an extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic catalytic domain. The receptor-type adenylyl cyclases are thought to have the ability to sense an extracellular signal and to control adenylyl cyclase activity of the catalytic domain. These enzymes were initially found in protozoans and have since been identified in eubacteria, although how the activity of these prokaryotic enzymes is regulated is unknown (23).

In M. xanthus, the cellular concentration of cAMP increases rapidly during early starvation-induced and glycerol-induced development (17, 34). Campos and Zusman also observed that the formation of fruiting bodies was stimulated by the addition of cAMP to agar containing a low level of nutrients (5). However, the adenylyl cyclase gene of M. xanthus has not been cloned. In a previous study, we cloned the mokA gene encoding an osmosensor histidine kinase from an M. xanthus genomic library (21). An open reading frame is present in the region of about 6 kb upstream of the mokA gene, and its deduced gene product (CyaA) showed a high degree of similarity with receptor-type adenylyl cyclase. In this paper, we report characterization of the cyaA gene and the finding that cyaA encodes a protein that senses osmolarity and regulates cAMP synthesis during spore germination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

M. xanthus IFO13542 (ATCC 25232) was used as the wild-type strain in this study. The M. xanthus wild-type or mutant strain was grown at 30°C in Casitone-yeast extract (CYE) medium (6), and kanamycin (70 μg/ml) was added when necessary.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

A positive clone which contains the mokA gene (21) was used in this experiment. Phage DNA was prepared from the clone and digested with KpnI, SalI, and SmaI. SalI (7.6-kb) and SmaI (2.3-kb) fragments were extracted from an 0.7% agarose gel. The DNA fragments were ligated into pBluescript SK and sequenced by the primer walking method using the ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Co., Norwalk, Conn.) with the BigDye terminator kit (Perkin-Elmer Co.).

Construction of cyaA disruption mutant.

To investigate the biological function of CyaA, we constructed a cyaA deletion-insertion mutant. First, a 2.2-kb fragment containing the cyaA gene was amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-GAAGCTGGGTGTCTACGACGC-3′ and 5′-TACGGCTTCTGCCACATGGG-3′. The PCR product was ligated into vector pT7 Blue1. This plasmid was designated pTCYA. Plasmid pTCYA was digested with BalI, and a 4.9-kb fragment was recovered from an agarose gel. A 1.2-kb DNA fragment containing a kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene was amplified by PCR with TnV as a template and a pair of primers (15). The resulting DNA fragment was inserted into the BalI site of pTCYA. The disrupted gene constructed as described above was amplified by PCR with the above oligonucleotides. The PCR products thus obtained were introduced into M. xanthus by electroporation (28).

Developmental assays.

M. xanthus wild-type and cyaA mutant strains were grown on CYE medium up to 5 × 108 cells/ml and washed in TM buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5] and 8 mM MgSO4). Aliquots (10 μl) of cell suspension (2 × 107 cells) were spotted on the surface of a clone fruiting (CF) agar plate or a CF agar plate containing up to 0.25 M NaCl or sucrose (16). The plates were incubated at 32°C. For glycerol induction of spore formation, cells were harvested at the mid-logarithmic phase of growth and washed with 1% Casitone-8 mM MgSO4, pH 7.6. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 0.5 M, and cells were shaken at 30°C for 10 h (13).

Spore germination.

M. xanthus spores were harvested from 7-day-old fruiting bodies. Undifferentiated cells were killed by five 30-s treatments with a Branson sonifier and by incubation at 60°C for 15 min. Spores were inoculated to 2 × 106 cells/ml in CYE medium containing up to 0.25 M NaCl or sucrose. The cultures were incubated at 30°C with continuous shaking until the germination in the medium without addition of NaCl or of sucrose was about 50%. The numbers of spores and vegetative cells were determined by counting with a hemacytometer.

Assays for cAMP accumulation.

Wild-type and mutant cells were cultured on CF agar for 6 or 22 h at 32°C. Cells were harvested and washed with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The cells were resuspended in the buffer and then stimulated with 0.2 M NaCl or sucrose. Aliquots (0.1 ml) containing 3 × 108 cells were taken at the respective time points and heated to 95°C for 10 min.

To obtain spores, vegetative cells were spotted on CF agar and cultured for 7 days. Spores were harvested and washed with TM buffer. After sonication and heat treatment, spores were cultured in CYE medium for 12 to 14 h, and then NaCl or sucrose was added to a final concentration of 0.2 M. Aliquots (1 ml) containing 2 × 108 spores were taken at various times, and the spores were washed with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), resuspended in 0.25 ml of the buffer, and then immediately sonicated with 0.2 g of acid-washed, 0.4-mm-diameter glass beads for 4 min at full power. Under this condition, approximately 95% of spores were disrupted. After centrifugation, a portion (80 μl) of the supernatant was mixed with 16 μl of perchloric acid (30% [vol/vol]) and then frozen. To determine the amount of cAMP, frozen samples were thawed, neutralized with KHCO3, and then centrifuged. Supernatants were used for assays with a commercial immunoassay kit (Amersham Pharmacia).

Time courses of cAMP levels under ionic-osmotic stress.

Intracellular cAMP levels were determined in wild-type and mutant cells during development and spore germination under ionic-osmotic stress. To measure cAMP production during development, vegetative cells were spotted on CF agar or CF agar containing 0.15 M NaCl. Cells were harvested at various times, washed once by centrifugation in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and suspended in 0.25 ml of the phosphate buffer. The cells were immediately sonicated with 0.2 g of glass beads for 4 min at full power. After centrifugation, a portion (80 μl) of the supernatant was mixed with perchloric acid and neutralized with KHCO3. After centrifugation, an 0.1-ml aliquot of the supernatant was assayed for cAMP as described above.

To estimate internal cAMP levels during germination, spores were inoculated in CYE medium or in CYE medium containing 0.2 M NaCl at 1.2 × 108 spores/ml and cultured at 30°C. Cells (1.8 × 108) were harvested by centrifugation at various times, washed once, and suspended in 250 μl of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Extraction and enzyme immunoassay of cAMP were performed by the above-mentioned method.

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford technique (4). Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results, and results of typical assays are shown.

Transcript analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from M. xanthus at exponential growth phase, at germination, and during development as described previously (22). Contaminating DNA was removed by digestion with DNase. For reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μg of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with BcaBEST polymerase in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan). PCR was performed with Bca-optimized Taq polymerase, a 5′ gene-specific primer (5′-ACACGGACATCTTCCGGC-3′), and a 3′ gene-specific primer (5′-GAAGCTGGGTGTCTACGACGC-3′). Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the M. xanthus cyaA gene has been deposited in the DDBJ sequence library under accession no. AB066096.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the cyaA gene from M. xanthus.

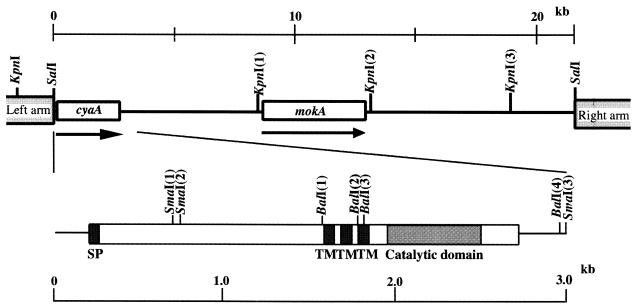

Recently, we cloned a histidine kinase gene (mokA) from a phage library of M. xanthus genomic DNA (21). On DNA analysis, we found that a 10-kb KpnI fragment of the cloned phage DNA contained an open reading frame the predicted amino acid sequence of which is homologous to adenylyl cyclases of prokaryotes and eukaryotes. We designated this gene cyaA. The restriction map of the cyaA gene and the positions of the mokA and cyaA genes are shown in Fig. 1. The nucleotide sequence of a 3.0-kb SalI-SmaI fragment of the 10-kb KpnI fragment DNA that contained the complete transcription unit was determined. The cyaA gene sequence predicts a protein composed of 843 amino acids, with a calculated molecular mass of 91,187 Da.

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the cloned phage DNA harboring the cyaA and mokA genes of M. xanthus. Lines with arrows indicate their orientations. The 0.25-kb BalI(1)-BalI(3) fragment was replaced by the Kmr gene. SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane domain.

Predicted protein structure and functional domains.

The predicted amino acid sequence of M. xanthus CyaA was compared with those in the DDBJ sequence library by using the BLASTP program. The amino-terminal region of the CyaA protein showed high homology with two potential sensor histidine kinases (25, 30) and a target protein of serine/threonine kinase (31) (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the cyaA gene product with the PSORT or SOSUI program suggested that CyaA possesses a signal peptide (Met-1 to Val-21) and three transmembrane regions (Leu-461 to Leu-483, Ala-490 to Phe-512, and Trp-518 to Tyr-540) that would place the protein in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 1).

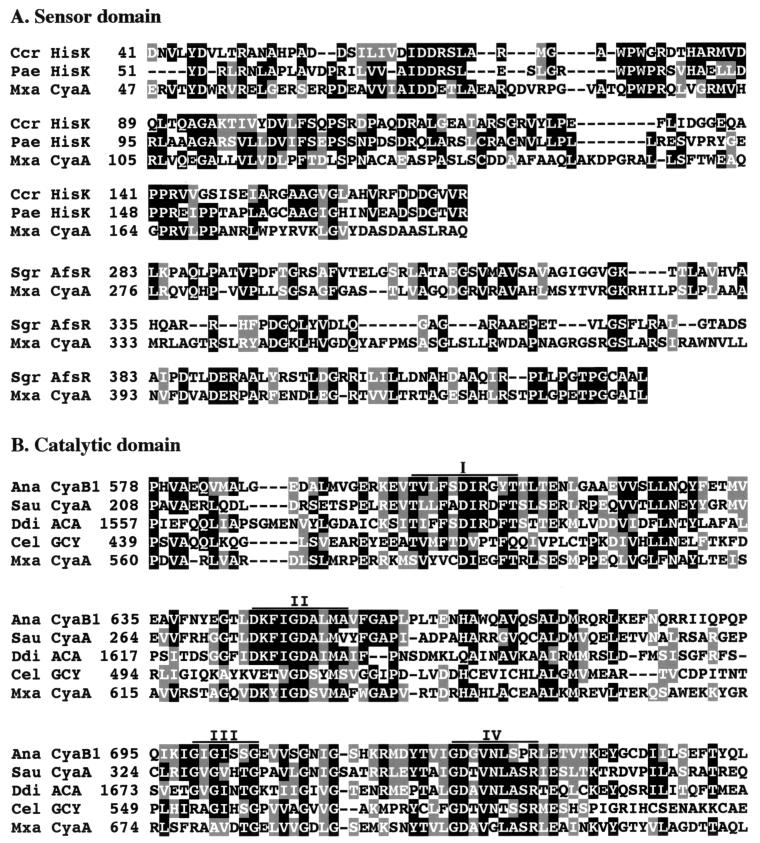

FIG. 2.

(A) Alignment of the deduced sensor domain of CyaA with the putative sensor histidine kinases HisK of Caulobacter crescentus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the target protein of serine/threonine kinase AfsR of Streptomyces griseus. (B) Alignment of the deduced catalytic domain of CyaA with the adenylyl cyclase CyaB1 of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120, the adenylyl cyclase CyaA of S. aurantiaca, the adenylyl cyclase ACA of D. discoideum, and the adenylyl-guanylyl cyclase GCY of C. elegans. Amino acid residues in agreement for more than three residues are indicated by black shading. Gray shading indicates degrees of similarity among amino acid residues. Four conserved motifs (I to IV) in class III adenylyl cyclases are overlined.

The carboxyl-terminal part of CyaA is a hydrophilic domain with a high degree of identity to the conserved catalytic domain of adenylyl cyclases from eukaryotes and eubacteria. The four regions conserved in class III adenylyl cyclases were found in the carboxyl-terminal region of CyaA. This region of CyaA shows 36.5% identity to the adenylyl cyclase CyaB1 of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (18), 34.5% identity to the adenylyl cyclase CyaA of Stigmatella aurantiaca (11), 28.5% identity to the adenylyl cyclase ACA of D. discoideum (27), and 23.5% identity to adenylyl-guanylyl cyclase GCY of Caenorhabditis elegans (7). Sequence alignments of carboxyl-terminal regions of these adenylyl cyclases are shown in Fig. 2B. No apparent sequence similarity with the E. coli adenylyl cyclase was found. These results suggested that the M. xanthus CyaA is a receptor-type adenylyl cyclase that belongs to the class III adenylyl cyclases as described by Danchin (12).

Stage-specific expression of CyaA.

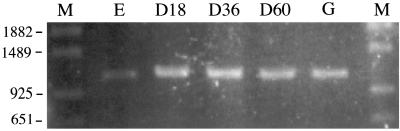

We investigated the expression of the cyaA gene in M. xanthus cells during growth, development, and spore germination by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3). The expected 1,190-bp RT-PCR products were mainly amplified from mRNA of developing and germinating cells. The cyaA gene was also expressed at a low level in vegetative cells. As a control, the expected product was not amplified without reverse transcription, indicating that there was no DNA contamination in the mRNA (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR analysis of cyaA gene expression in M. xanthus. Total RNAs prepared from cultures at exponential growth phase (E); at germination (G); and during development at 18 (D18), 36 (D36), and 60 (D60) h were used for RT-PCR analysis. Molecular sizes (M) of DNA fragments are given in bases.

Effect of disruption of cyaA on development.

As described in Materials and Methods, the cyaA gene on the chromosome was disrupted by insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene from TnV. Using Southern hybridization and PCR analysis, we confirmed that the kanamycin resistance gene was inserted into the cyaA gene (data not shown). To study the function of CyaA in development, wild-type and cyaA mutant strains were cultured on starvation medium (CF agar). When wild-type cells were allowed to develop on CF agar, aggregations and fruiting bodies were formed at approximately 12 to 24 and 40 to 65 h, respectively. The cyaA mutant showed the normal developmental process, and the morphology of the fruiting body of the mutant strain was similar to that of the wild-type strain. The final yield of spores for the cyaA mutant was also identical to that of the wild-type strain. During development under nonosmolarity, there were no significant differences in cellular cAMP levels between the wild-type and mutant cells (see Fig. 7). In glycerol-containing medium, the cyaA mutant was also able to form spores. When cultured in CYE growth medium, the mutant grew as well as did the wild type.

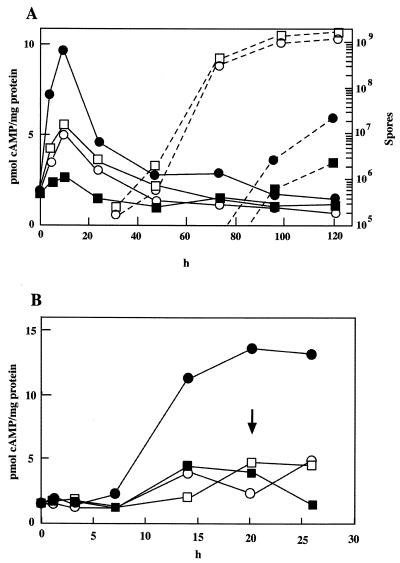

FIG. 7.

Changes in intracellular cAMP levels in wild-type and cyaA mutant strains during development and germination under ionic osmostress. (A) Wild-type (circles) and cyaA mutant (squares) cells were developed on CF agar (open symbols) or on CF agar containing 0.15 M NaCl (solid symbols), and intracellular cAMP levels (solid lines) and numbers of spores (dashed lines) were determined at the time points indicated in the figure. (B) Wild-type (circles) and cyaA mutant (squares) spores were incubated in CYE medium (open symbols) or in CYE medium containing 0.2 M NaCl (solid symbols), and intracellular cAMP levels were determined at the time points indicated in the figure. The arrow indicates the time at which rod-shaped cells were seen in cultures with no addition of NaCl.

Osmosensitivity of the cyaA mutant.

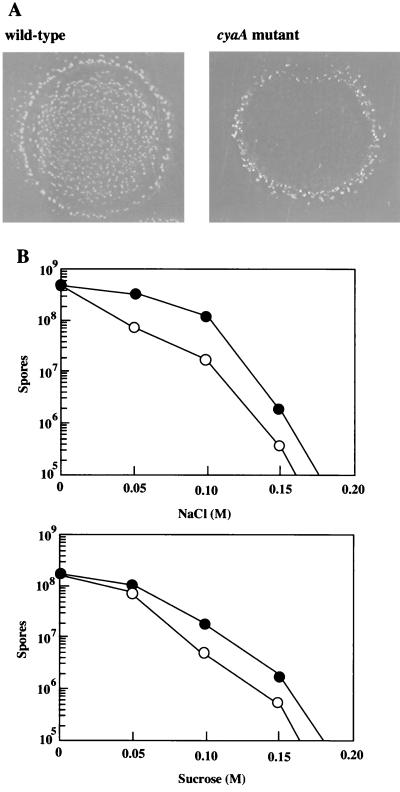

Adenylyl cyclases of Trypanosoma brucei, Leishmania donovani, and D. discoideum, which have a large extracellular domain, are considered to function as receptors or as sensors (2, 29, 32). Since the structure of M. xanthus CyaA is similar to those of receptor- or sensor-type adenylyl cyclases, we investigated the phenotypic differences between wild-type and cyaA mutant strains under various stresses. The vegetative cells of the cyaA mutant were found to be reasonably normal with respect to stresses such as temperature shifts, pH changes, osmotic pressure, and anaerobic culture (data not shown). However, the cyaA mutant showed an osmosensitive phenotype during development and germination. Figure 4A shows fruiting bodies of the wild type and the cyaA mutant on CF agar plates containing 0.1 M NaCl. The wild-type strain formed normal fruiting bodies about 1 day later than did the wild-type strain in the nonosmotic medium. In contrast, fruiting bodies of the mutant strain were formed around the spot only after incubation for 3 to 4 days. As a result, the spore yield of the mutant strain was approximately 15% of that of the wild-type strain at 5 days after inoculation onto CF agar plates containing 0.1 M NaCl (Fig. 4B). Moreover, when the cyaA mutant cells were developed on CF agar containing 0.1 to 0.15 M sucrose, spore numbers of the mutant were one-third to one-fourth of those of the wild type.

FIG. 4.

(A) Fruiting bodies of wild-type and cyaA mutant strains under high-ionic osmolarity. Vegetative cells were spotted on CF agar containing 0.1 M NaCl. Photographs of fruiting bodies were taken after 5 days of incubation. (B) Spore formation of M. xanthus wild type (solid circles) and cyaA mutant (open circles) on CF agar containing various concentrations of NaCl or sucrose. Spores were counted at 5 days of development with a hemacytometer.

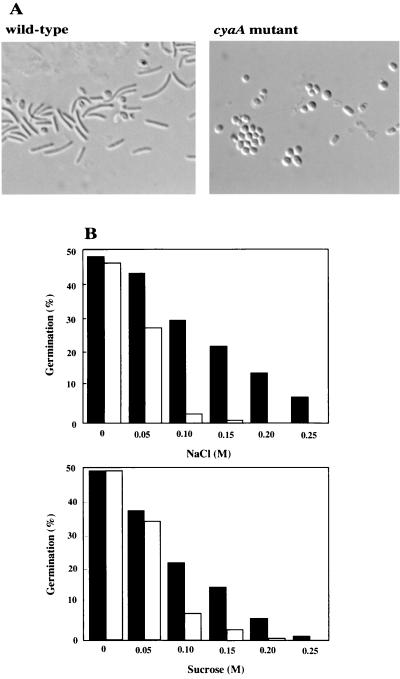

When wild-type spores were incubated in CYE medium containing 0.2 M NaCl for 65 h, more than 90% of the spores were elongated into rod-shaped structures (Fig. 5A). Under this condition, only a minor population of mutant spores was converted into vegetative-cell-like cells. Figure 5B shows the rates of germination in wild-type and cyaA mutant spores at various NaCl concentrations. The rate of germination of wild-type spores decreased with increasing NaCl concentration, and almost all spores did not germinate in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl. In the presence of 0.1 and 0.15 M NaCl in CYE medium, the rate of germination of mutant spores showed nearly a 10-fold decrease compared with that of wild-type spores. The mutant showed little or no germination on CYE medium containing 0.2 or 0.25 M NaCl, respectively. In CYE medium containing more than 0.1 M sucrose, the cyaA mutant spores also germinated poorly compared with the wild-type spores, as shown in Fig. 5B. However, the spore germination of the cyaA mutant was more strongly inhibited by NaCl than by sucrose.

FIG. 5.

(A) Germination of myxospores under high-ionic osmolarity. Photographs of spore germination were taken after 65 h of incubation with 0.2 M NaCl. (B) Spore germination of M. xanthus wild-type (solid bars) and cyaA mutant (open bars) spores in CYE medium containing various concentrations of NaCl or sucrose. Percent germination of each strain was determined by counting with a hemacytometer.

Assays for cAMP accumulation.

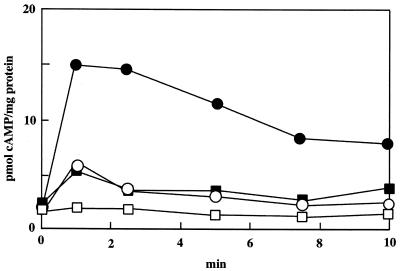

cAMP production by spores was measured during a period of 10 min after osmotic stimulation (Fig. 6). In the response experiment, wild-type and mutant spores, in which germination programs progressed by incubation for 12 h in CYE medium, were used. In wild-type spores, addition of 0.2 M NaCl resulted in a rapid increase in cAMP level, which peaked at 1 min and slowly decreased thereafter. In contrast, cAMP production by mutant spores was only weakly stimulated by addition of 0.2 M NaCl. Addition of 0.2 M sucrose to wild-type spores induced an up-to-threefold increase in the accumulation of cAMP, but the accumulated cAMP levels were lower than those with NaCl stimulation.

FIG. 6.

Assays for cAMP accumulation in wild-type and cyaA mutant spores. After wild-type spores (circles) and cyaA mutant spores (squares) were incubated in CYE medium for 12 h, 0.2 M NaCl (solid symbols) or 0.2 M sucrose (open symbols) was added to both cultures. Spores were assayed for total accumulated cAMP levels.

We also measured whether CyaA activity during development is regulated by high osmolarity. When 0.2 M NaCl or sucrose was added to developing cells, cAMP increased linearly for at least 60 min of incubation, resulting in accumulated cAMP levels of about 8 to 12 or 20 to 30 pmol/mg of protein, respectively. There was no significant difference in the amounts of cAMP accumulation between wild-type and cyaA mutant cells (data not shown).

Time courses of cAMP levels during development and germination in high salt.

We next determined cAMP levels in wild-type and cyaA mutant cells during development and spore germination under ionic osmostress. Wild-type and cyaA mutant cells were cultured on CF agar or CF agar containing 0.15 M NaCl, and intracellular cAMP levels were determined over a time course of 120 h (Fig. 7A). In nonosmotic conditions, the intracellular cAMP levels of wild-type and cyaA mutant strains increased two- to threefold during the first 12 h of incubation. In the presence of NaCl accumulated cAMP levels of the wild-type strain were about twofold higher than those in its absence, and the cAMP accumulation stimulated by 0.15 M NaCl could be detected by 72 h of development. In contrast, the cyaA mutant developed under high osmolarity showed no increased intracellular cAMP levels during early stages of development, which was possibly due to damage of osmosensitive mutant cells.

Wild-type and cyaA mutant spores were germinated in CYE medium or in CYE medium containing 0.2 M NaCl, and the changes in intracellular cAMP levels were determined. As shown in Fig. 7B, the cAMP levels of wild-type spores under osmotic stress increased rapidly from 7 to 14 h of incubation and reached a maximum level at 20 h or approximately at the time of initiation of nonosmotic spore germination. The spores at the early stage of germination may not be susceptible to stimulation by osmolarity, because the spores are covered with thick spore coats. In contrast, adenylyl cyclase activity of cyaA mutant spores was not stimulated by 0.2 M NaCl, and the changes in cAMP levels of mutant spores during germination were similar to those of nonosmotically stressed wild-type and mutant spores. There was a three- to fourfold difference in cAMP level at 20 h between wild-type and cyaA mutant spores under ionic osmostress. When wild-type and cyaA mutant spores were incubated in the absence of NaCl for 20 or 26 h, the percentages of rod-shaped cells in each culture were 0.25 and 0.28% and 5 and 7%, respectively (data not shown). By 26 h of incubation, no vegetative-cell-like cells of either strain were observed in the cultures with 0.2 M NaCl. As heat-treated spores were used in this experiment, germination proceeded slowly compared with that of non-heat-treated spores (26).

In the developmental or germination time course of cAMP levels, mutant cells under high-ionic osmolarity showed significantly lower levels of cAMP accumulation than did wild-type cells, indicating that cAMP accumulation plays a role in enhancement of osmotic tolerance during development and germination.

DISCUSSION

In the eukaryotic slime mold D. discoideum, cAMP coordinates the stages of the developmental program, and an adenylyl cyclase, ACA, is expressed during early aggregation (27). The proposed structure of ACA resembles those of typical mammalian adenylyl cyclases, and the ACA-null mutant has little detectable adenylyl cyclase activity during aggregation and fails to aggregate. The myxobacterium M. xanthus has a developmental cycle that resembles that of D. discoideum. During development, cAMP levels in M. xanthus increase by about 2- to 20-fold early in development, and cAMP stimulates fruiting body formation when added to low-nutrient or nonnutrient medium (5, 17, 34). Although activation of adenylyl cyclase and accumulation of cAMP are likely to be required for the development of M. xanthus as well as of D. discoideum, it was difficult to demonstrate this assumption directly because the adenylyl cyclase gene had not been cloned in M. xanthus. In this study, we cloned an adenylyl cyclase (cyaA) gene from M. xanthus, constructed a cyaA mutant by gene disruption, and used the mutant for a developmental assay. cyaA was expressed during development, but the cyaA mutant was able to undergo normal development and exhibited cAMP production similar to that of the wild-type strain during development. These results indicated that M. xanthus CyaA is not involved in the production of cAMP during development and that another adenylyl cyclase produces cAMP during development. Several prokaryotes have been reported elsewhere to possess multiple adenylyl cyclase genes (8, 18).

Hydropathy profile analysis suggested that M. xanthus CyaA possesses three potential transmembrane regions that connect an extracellular domain in the amino-terminal region to an internal catalytic domain in the carboxyl-terminal region. This structure is often found in the receptor-type guanylyl cyclases of eukaryotes. As M. xanthus CyaA is thought to be a receptor-type adenylyl cyclase, this implies that CyaA has the ability to sense an extracellular signal and control adenylyl cyclase activity. Mutation of cyaA caused significant reduction of fruiting body formation, spore formation, and spore germination at high osmolarity. The phenotypes of the mutant would not be due to polar effects, because there was no open reading frame that formed an operon with the cyaA gene. We next investigated whether CyaA was a sensor for osmolarity and was regulated by high osmolarity. When spores cultured in growth media were incubated at high osmolarity, there was an apparent difference in cAMP accumulation between wild-type and cyaA mutant strains. In wild-type spores, high osmolarity caused a rapid cAMP increase which peaked at 1 min and then slowly declined. The cAMP accumulation in wild-type cells was much more strongly stimulated by NaCl than by sucrose. In contrast, the mutant cells showed only weak NaCl-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. On the other hand, cAMP accumulation in cyaA mutant cells at developmental stages was stimulated by 0.2 M NaCl or sucrose, and the stimulated cAMP levels were similar to those of wild-type cells. Since the levels of cAMP accumulation were increased until at least 60 min after stimulation, the cAMP accumulation would be due to other adenylyl cyclases. However, the cyaA gene was expressed during development, and the cyaA mutant cells at developmental stages showed an osmosensitive phenotype. In addition, when wild-type and mutant cells were developed under high-ionic osmolarity, the mutant cells showed significantly lower intracellular cAMP levels than did the wild-type cells during the developmental period. These results indicate that CyaA also has a function in osmotic tolerance during development.

Receptor-type adenylyl cyclase genes have been cloned from protozoans, D. discoideum, and eubacteria. A receptor-type adenylyl cyclase, ACG, of D. discoideum is expressed only during germination and acts as an osmosensor that controls spore germination (32). No apparent sequence similarity in the sensor domain was found between CyaA of M. xanthus and ACG of D. discoideum.

In summary, our results indicated that M. xanthus CyaA is a transmembrane osmosensor protein during germination that directly produces cAMP in response to osmotic pressure that contributes to the osmotic tolerance of germinating cells. As far as we know, our results represent the first demonstration of an adenylyl cyclase that acts as a sensor in a prokaryote. The signal transduction pathway for osmoregulation of germination in D. discoideum is assumed to be as follows: the increased intracellular cAMP by osmotic stress activates a cAMP-dependent protein kinase (protein kinase A [PKA]), and the activated PKA inhibits spore germination (32). The first prokaryote protein serine/threonine kinase was discovered in M. xanthus, and at least 11 serine/threonine kinase genes have been submitted to the DDBJ sequence library. We are currently investigating whether M. xanthus possesses a cAMP-PKA pathway for osmotic transduction of development and germination.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., K. Mori, M. Tanaka, T. Ooi, A. Roy, and A. Danchin. 1984. The complete nucleotide sequence of the adenylate cyclase genes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:9427-9440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre, S., P. Paindavoine, P. Tebabi, A. Pays, S. Halleux, M. Steinert, and E. Pays. 1990. Differential expression of a family of putative adenylate/guanylate cyclase genes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 43:279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borges-Walmsley, M., and A. R. Walmsley. 2000. cAMP signaling in pathogenic fungi: control of dimorphic switching and pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 8:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos, J. M., and D. R. Zusman. 1975. Regulation of development in Myxococcus xanthus: effect of 3′:5′-cyclic AMP, ADP, and nutrition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:518-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos, J. M., J. Geisselsoder, and D. R. Zusman. 1978. Isolation of bacteriophage MX4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J. Mol. Biol. 119:167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. 1998. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science 282:2012-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLeah, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Soeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, D. M. F., N. Mons, and J. W. Karpen. 1995. Adenylyl cyclases and the interaction between calcium and cAMP signaling. Nature 374:421-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter, D. A., A. J. Dunbar, S. T. Buconjic, and J. F. Wheldrake. 1999. Ammonium phosphate in sori of Dictyostelium discoideum promotes spore dormancy through stimulation of the osmosensor ACG. Microbiology 145:1891-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coudart-Cavalli, M. P., O. Sismeiro, and A. Danchin. 1997. Bifunctional structure of two adenylyl cyclases from the myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca. Biochimie 79:757-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danchin, A. 1993. Phylogeny of adenylyl cyclases. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprot. Res. 27:109-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin, M., and S. M. Gibson. 1964. A system for studying microbial morphogenesis: rapid formation of microcysts in Myxococcus xanthus. Science 146:243-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firtel, R. A. 1995. Interacting signalling pathways controlling multicellular development in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 9:1427-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furuichi, T., M. Inouye, and S. Inouye. 1985. Novel one-step cloning vector with a transposable element: application to the Myxococcus xanthus genome. J. Bacteriol. 164:270-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagen, C. D., P. A. Bretscher, and D. Kaiser. 1979. Synergism between morphogenic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev. Biol. 64:284-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho, J., and H. D. McCurdy. 1980. Sequential changes in the cyclic nucleotide levels and cyclic phosphodiesterase activities during development of M. xanthus. Curr. Microbiol. 3:197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katayama, M., and M. Ohmori. 1997. Isolation and characterization of multiple adenylate cyclase genes from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 179:3588-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearns, D. B., and L. J. Shimkets. 2001. Lipid chemotaxis and signal transduction in Myxococcus xanthus. Trends Microbiol. 9:126-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimata, K., H. Takahashi, T. Inada, P. Postma, and H. Aiba. 1997. cAMP receptor protein-cAMP plays a crucial role in glucose-lactose diauxie by activating the major glucose transporter gene in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12914-12919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura, Y., H. Nakano, H. Terasaka, and K. Takegawa. 2001. Myxococcus xanthus mokA encodes a histidine kinase-response regulator hybrid sensor required for development and osmotic tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 183:1140-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, M., and L. Shimkets. 1994. Cloning and characterization of the socA locus which restores development to Myxococcus xanthus C-signaling mutants. J. Bacteriol. 176:2200-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCue, L. A., K. A. McDonough, and C. E. Lawrence. 2000. Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 10:204-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz-Dorado, J., S. Inouye, and M. Inouye. 1991. A gene encoding a protein serine/threonine kinase is required for normal development of M. xanthus, a gram-negative bacterium. Cell 67:995-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nierman, W. C., T. V. Feldblyum, M. T. Laub, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, J. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, M. R. K. Alley, N. Ohta, J. R. Maddock, I. Potocka, W. C. Nelson, A. Newton, C. Stephens, N. D. Phadke, B. Ely, R. T. DeBoy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, J. F. Kolonay, J. Smit, M. Craven, H. Khouri, J. Shetty, K. Berry, T. Utterback, K. Tran, A. Wolf, J. Vamathevan, M. Ermolaeva, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, J. C. Venter, L. Shapiro, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4136-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otani, M., M. Inouye, and S. Inouye. 1995. Germination of myxospores from the fruiting bodies of Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 177:4261-4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitt, G. S., N. Milona, J. Borleis, K. C. Lin, R. R. Reed, and P. N. Derveotes. 1992. Structurally distinct and stage-specific adenylyl cyclase genes play different roles in Dictyostelium development. Cell 69:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plamann, L., A. Kuspa, and D. Kaiser. 1992. The Myxococcus xanthus asgA gene encodes a novel signal transduction protein required for multicellular development. J. Bacteriol. 174:3311-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez, M. A., D. Zeoli, E. M. Klamo, M. P. Kavanaugh, and S. M. Landfear. 1995. A family of putative receptor-adenylate cyclase from Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17551-17558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stover, C. K., X.-Q. T. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. L. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrook-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. M. Lim, K A. Smith, D. H. Spencer, G. K.-S. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. W. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umeyama, T., P. Lee, K. Ueda, and S. Horinouchi. 1999. An AfsK/AfsR system involved in the response of aerial mycelium formation to glucose in Streptomyces griseus. Microbiology 145:2281-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Es, A., K. J. Virdy, G. S. Pitt, M. Meima, T. W. Sands, P. N. Devreotes, D. A. Cotter, and P. Schaap. 1996. Adenylyl cyclase G, an osmosensor controlling germination of Dictyostelium spores. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23623-23625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virdy, K. J., T. W. Sands, S. H. Kopko, S. van Es, M. Meima, P. Schaap, and D. A. Cotter. 1999. High cAMP in spores of Dictyostelium discoideum: association with spore dormancy and inhibition of germination. Microbiology 145:1883-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yajko, D. M., and D. R. Zusman. 1978. Changes in cyclic AMP levels during development in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 133:1540-1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]