Abstract

HoxN, a high-affinity, nickel-specific permease of Ralstonia eutropha H16, and NhlF, a nickel/cobalt permease of Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1, are structurally related members of the nickel/cobalt transporter (NiCoT) family. These transporters have an eight-helix structure and are characterized by highly conserved segments with polar or charged amino acid residues in transmembrane domains (TMDs) II, III, V, and VI. Two histidine residues in a Ni2+ binding motif, the signature sequence of NiCoTs, in TMD II of HoxN have been shown to be crucial for activity. Replacement of the corresponding His residues in NhlF affected both Co2+ and Ni2+ uptake, demonstrating that NhlF employs a HoxN-like mechanism for transport of the two cations. Multiple alignments of bacterial NiCoT sequences identified a striking correlation between a hydrophobic residue (Val or Phe) in TMD II and a position in the center of TMD I occupied by either an Asn (as in HoxN) or a His (as in NhlF). Introducing an isoleucine residue at the latter position strongly reduced HoxN activity and abolished NhlF activity, suggesting that a Lewis base N-donor moiety is important. The Asn-to-His exchange had no effect on HoxN, whereas the converse replacement reduced NhlF-mediated Ni2+ uptake significantly. Replacement of the entire TMD I of HoxN by the respective NhlF segment resulted in a chimera that transported Ni2+ and Co2+ with low capacity. The Val-to-Phe exchange in TMD II of HoxN led to a considerable rise in Ni2+ uptake capacity and conferred to the variant the ability to transport Co2+. NhlF activity dropped in response to the converse mutation. Our data predict that TMDs I and II in NiCoTs spatially interact to form a critical part of the selectivity filter. As seen for the V64F variant of HoxN, modification of this site can increase the velocity of transport and concomitantly reduce the specificity.

In the functional phylogenetic transporter classification system developed by Saier (26, 27), the family with the code TC 2.A.52 is described as the nickel/cobalt transporter (NiCoT) family. The family comprises structurally related membrane proteins in gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, in archaea, and in fungi. An eight-helix structure, conserved signatures containing charged residues in transmembrane domains (TMDs), and a large hydrophilic loop connecting TMDs IV and V are common features of the members of this family (reviewed in references 5, 8, and 9). High-affinity Ni2+ uptake to provide the metal ion for incorporation into Ni-containing metalloenzymes (see reference 14 for a review) is the physiological role of the NiCoTs of Ralstonia eutropha (HoxN), Helicobacter pylori (NixA), and the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Despite the family name, HoxN acts as a selective Ni2+ permease and does not transport Co2+ (4). NixA activity in the human pathogen H. pylori is essential to virulence, since nickel-containing urease is a central pathogenicity determinant in this species. Site-directed mutagenesis has been employed to localize residues and motifs in HoxN (10) and NixA (12) that cannot be altered without a dramatic or complete loss of activity. These studies uncovered the relevance of a strongly conserved segment (GLR/KHAV/FDADHI/LAAI) in TMD II that can be considered a signature sequence for NiCoTs. NhlF, the NiCoT of the gram-positive Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1, provides Co2+ ion for incorporation into Co2+-containing nitrile hydratases (17), industrial catalysts that contain a non-corrin cobalt metallocenter (reviewed in reference 16). In contrast to HoxN, NhlF is literally a NiCoT and transports Ni2+ and Co2+ with high affinity (4).

Experimental analysis of NiCoT activity is difficult. These permeases transport their substrates with very high affinity but extremely low capacity. For reproducible measurement of HoxN activity, hoxN has been expressed in Escherichia coli and metal uptake has been analyzed during growth in complex medium (33). At a 63Ni2+ concentration of 500 nM in the growth medium, the resulting cellular 63Ni content was in the range of 25 to 50 pmol per mg of protein, corresponding to approximately 2,500 to 5,000 Ni2+ ions per cell. These values are not markedly affected by the optical density of the cultures unless the cells reached the very late exponential phase. The experiments have confirmed the exceptionally low capacity of HoxN-mediated metal transport. Signal-to-noise ratios (>15:1) in analyses of HoxN (4, 10, 33) and NhlF activity (4) obtained with this assay were much higher than those obtained with standard transport assays by using nongrowing bacterial cell suspensions. Experiments during the characterization of a nickel transport-deficient mutant of fission yeast (6) have confirmed the sensitivity and reproducibility of this method as a measure for Ni2+ uptake.

In the present study, we attempted to gain insight into the basis of the exceptionally high selectivity of NiCoTs. We used metal accumulation assays to characterize HoxN and NhlF mutant and chimeric permeases in order to identify recognition domains responsible for the different substrate profiles of the two NiCoTs. Evidence is presented that residues in TMDs I and II interact and form a critical part of the selectivity filter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) and CC118 (21) were used for gene cloning. For metal accumulation tests, urease assays, and Western blot analysis, variants of HoxN and NhlF were produced in E. coli CC118, a strain that lacks the entire lac operon, including lacI, due to the lacX74 deletion. Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml).

Plasmid constructions.

Relevant plasmids are listed in Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers used for mutagenesis are listed in Table 2. The plasmids constructed in this study are derivatives of pCH674 and pCH675, containing nhlF and hoxN, respectively, under the control of a lac promoter and a bacterial ribosomal binding site in a derivative of vector pBluescript KS(+) that confers streptomycin resistance (4). The respective derivatives that confer ampicillin resistance contain essentially the same inserts in vector pBluescript II KS(+) and were designated pCH674A and pCH675A. For production of FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK)-tagged NhlF and HoxN, 24 bp were inserted between the last codon and the stop codon in nhlF and hoxN by PCR with Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and primers 12 (nhlF) and 13 (hoxN) in combination with standard reverse primer. The purified PCR products were digested with HindIII/XbaI (nhlF) and EcoRI/XbaI (hoxN) and used to replace the respective segments of pCH674A and pCH675A. The resulting plasmids were designated pCH674AF and pCH675AF. The relevant segments were verified by sequence determination.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCH674 | lac promoter, nhlF; confers streptomycin resistance | 4 |

| pCH675 | lac promoter, hoxN; confers streptomycin resistance | 4 |

| pCH434L117 | hoxN codons 1-117, 12-nt linker with BamHI site, lacZ | 7 |

| pCH434L167 | hoxN codons 1-167, 12-nt linker with BamHI site, lacZ | 7 |

| pKAU17 | lac promoter, Klebsiella aerogenes urease operon in vector pUC8; confers ampicillin resistance | 22 |

| pCH674A | Derivative of pCH674, confers ampicillin resistance | This study |

| pCH675A | Derivative of pCH675, confers ampicillin resistance | This study |

| pCH674AF | Derivative of pCH674A, codes for FLAG-tagged NhlF | This study |

| pCH675AF | Derivative of pCH675A, codes for FLAG-tagged HoxN | This study |

| pNhlFH34I | Derivative of pCH674A, nhlF H34I | This study |

| pNhlFH34N | Derivative of pCH674A, nhlF H34N | This study |

| pNhlFH68IF | Derivative of pCH674A, nhlF H68I, FLAG tag | This study |

| pNhlFF70V | Derivative of pCH674A, nhlF F70V | This study |

| pNhlFH74IF | Derivative of pCH674A, nhlF H74I, FLAG tag | This study |

| pHoxNN31H | Derivative of pCH675A, hoxN N31H | This study |

| pHoxNN31I | Derivative of pCH675A, hoxN N31I | This study |

| pHoxNV64F | Derivative of pCH675A, hoxN V64F | This study |

| pChi1 | Derivative of pCH674AF, nhlF (nt 1-156) fused to hoxN (nt 139-1056) | This study |

| pChi2 | Derivative of pCH674AF, nhlF (nt 1-471) fused to hoxN (nt 451-1056) | This study |

| pChi3 | Derivative of pCH675AF, hoxN (nt 1-351), 12-nt linker encoding PGDP, nhlF (nt 376-1059) | This study |

| pChi4 | Derivative of pCH675AF, hoxN (nt 1-501), 12-nt linker encoding PGDP, nhlF (nt 529-1059) | This study |

nt, nucleotide(s).

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer no. | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Application |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAGCCAGGCGCCGATGTGGAATGCAATCAGCAG (−) | HoxN N31H |

| 2 | GAGCCAGGCGCCGATAATGAATGCAATCAGCAG (−) | HoxN N31I |

| 3 | CGCATGAATTCTACTGGCC (+) | HoxN N31H, N31I |

| 4 | TTGCGCCACGCGTTCGACGCAGATCATCTCGC (+) | HoxN V64F |

| 5 | CCATGACAGCGATCAGC (−) | HoxN V64F, N31H, N31I |

| 6 | GTTCGTCACGCAGTCGACGCCGACCACATCGC (+) | NhlF F70V |

| 7 | GCCACGCCCAAGACGTTCAGGATCACGATGGCAC (−) | NhlF H34N |

| 8 | GCCCAAGACGATCAGGATCACGATGGC (−) | NhlF H34I |

| 9 | CGGCGTCGAATGCGATACGAACGCCGAGCA (−) | NhlF H68I |

| 10 | CGATTGCCGCGATGATGTCGGCGTCGAATGC (−) | NhlF H74I |

| 11 | CGAGTGTCCCATCGCGAAG (−) | Replacements in NhlF |

| 12 | CGCTCTAGATCACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCGTTCCGTTGAGGTTTCAGG (−) | NhlF FLAG tagging |

| 13 | CGCTCTAGACTCACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCGGCACGCACTTCGCTGTCGTC (−) | HoxN FLAG tagging |

| 14 | GCGCGGCCGGGGTGCTGCTCGGCACC (+) | Chimera 1 |

| 15 | GCTCGGCGTATCGGGCGTTC (+) | Chimera 2 |

| 16 | GGCGGATCCACTCGAAGGAGTACAGGAAATCG (+) | Chimera 3 |

| 17 | GGCGGATCCCGAGAGCAGACTCAGTGAGCG (+) | Chimera 4 |

| 18 | CGCAAGCTTTAAGGAGGAATAGCGTATGTTCCAATTGCTCGC (+) | Chimeras 3 and 4 |

Altered bases are shown in boldface type. Underlined bases represent the antisense strand of the FLAG epitope-encoding sequence. (−), antisense strand; (+), sense strand.

Single-codon replacements were introduced by two rounds of PCR as described previously (10). Pfx DNA polymerase was used for amplification. Point mutations were verified by nucleotide sequencing. hoxN N31H and N31I mutations were generated with combinations of primers 1 and 3 and 2 and 3, respectively. The purified amplimers were used as primers in the second rounds of PCR in combination with primer 5. The resulting products were digested with EcoRI and MscI and inserted into the EcoRI/MscI-treated pCH675A. Primers 4 and 5 and standard reverse primer were used to construct hoxN V64F. The HindIII/MscI-digested product of the second PCR round was used to replace the respective fragment of pCH675A. Mutagenic oligonucleotides 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, primer 11, and standard reverse primer were employed for the generation of nhlF point mutations. The mutated alleles were inserted into pCH674A or pCH674AF after treatment with HindIII/NruI (F70V and H34N) or ClaI/NruI (H34I, H68I, and H74I).

Plasmids encoding chimeric permeases were generated as follows. pChi1 was constructed in two steps. In the first step, a ScaI/EagI fragment of pCH674A was subcloned in vector pBluescript II SK(+). Finally, a PCR product generated with primer 14, standard universal forward primer, and pCH675AF as the template was digested with EagI and XbaI and inserted into the intermediate plasmid to give pChi1. pChi2 was assembled by inserting a blunt/XbaI fragment, obtained by amplification of pCH675AF in the presence of primer 15 and standard universal forward primer and subsequent digestion with XbaI, into the FspI/XbaI-treated pCH674A. Generation of pChi3 and pChi4 took advantage of the previously described fusions of a BamHI site-flanked lacZ to hoxN codons 117 and 167 in plasmids pCH434L117 and pCH434L167 (7). The hoxN-lacZ fusions were amplified with primer 18 and universal forward primer, digested with HindIII and XbaI, and inserted into vector pBluescript II KS(+). The resulting intermediates were used to insert BamHI/XbaI-digested amplicons obtained by PCR with pCH674AF as the template and primer pairs 16-universal forward and 17-universal forward to yield pChi3 and pChi4, respectively.

DNA sequencing.

Nucleotide sequences were determined by cycle sequencing in the presence of an infrared dye-labeled primer and subsequent usage of an automatic sequencer (LI-COR DNA4000).

Assays.

63Ni2+ and 57Co2+ accumulation of E. coli CC118 expressing hoxN, nhlF, or derivatives was analyzed as described previously (4, 10, 33). Briefly, cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth in the presence of an appropriate antibiotic and 63NiCl2 (24 TBq/mol) or 57CoCl2 (1 to 13 TBq/mol) at the indicated concentrations. To avoid artifacts due to variations of the metal-complexing properties of the Luria-Bertani medium, sterilized liquid medium from the same bottle was used each time when metal uptake of wild-type and mutant permeases was compared. Radioactivity of washed and concentrated cells was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting in a Canberra-Packard TRI-CARB 2000TR counter. Metal accumulation is expressed as picomoles of metal ion taken up per milligram of protein. Each data point represents the mean of double or triple determinations with independent cultures grown in the same lot of medium. Protein was estimated by a modified Lowry procedure (24) by using a commercial kit according to the manufacturer's (Sigma) recommendations. The urease activity of E. coli CC118 expressing the urease operon from pKAU17 and hoxN, nhlF, or variants from a plasmid that confers streptomycin resistance was measured as described previously (33).

Solubilization of membrane proteins and Western blotting.

To analyze the expression and stability of mutant and chimeric permeases, FLAG-tagged copies were produced in E. coli CC118. Cells were grown in 20 ml of Luria-Bertani broth to an optical density at 578 nm of approximately 1.8, washed twice with 5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (35 mM, pH 7.0), and resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer containing a mixture of protease inhibitors for bacterial cell extracts, as recommended by the manufacturer (Sigma). Cells were disrupted by sonication, and cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation (800 × g at 4°C, twice). Membranes in the supernatant were pelleted by high-speed centrifugation in a tabletop centrifuge (21,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h). Membrane protein was solubilized by stirring at 4°C for 2 h after the addition of 100 μl of solubilization buffer (10 mM Tris-hydrochloride, 10 mM EDTA, 3% [wt/vol] glycerol, 2% [wt/vol] lithium dodecyl sulfate, protease inhibitors; pH 6.8). Nonsolubilized material was pelleted by centrifugation (21,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h). Ten micrograms of solubilized membrane protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the method of Laemmli (18). Proteins were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. FLAG-tagged permeases were visualized by using monoclonal anti-FLAG Bio M2 antibody (Sigma), alkaline phosphatase-coupled goat anti-mouse conjugate (Promega), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride solution.

RESULTS

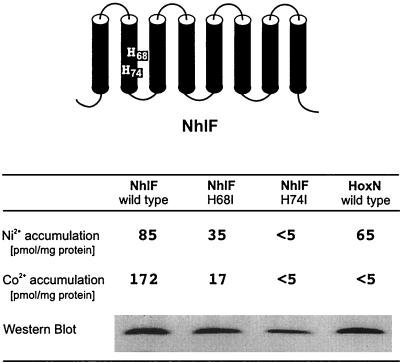

Histidine residues in TMD II of NhlF are critical for transport activity.

NhlF was originally described as a selective Co2+ permease in the actinomycete R. rhodochrous J1 (17). Later, a detailed analysis of its substrate spectrum revealed that, in addition to Co2+, Ni2+ ion is transported by NhlF with high affinity (4). Amino acid sequence and hydropathy profile alignments showed a close relationship between NhlF and other members of the NiCoT family (4, 9). The two histidines and flanking residues within TMD II of NiCoTs are conserved in NhlF. These residues have been shown to play a central role in high-affinity nickel transport of H. pylori NixA (12, 13) and R. eutropha HoxN (10). Replacement of HoxN His-62 strongly reduced the affinity of the permease for the Ni2+ ion, and alteration of His-68 completely abolished transport activity. To examine the consequences of exchanges of the corresponding His residues for NhlF activity, we introduced individual His-to-Ile mutations at positions 68 and 74 and analyzed the Ni2+ and Co2+ transport activities of the resulting permeases in the E. coli system. The results are shown in Fig. 1. Both Ni2+ and Co2+ transport activity were diminished to background levels in the strain producing NhlF H74I. Although there was somewhat less protein detected in the case of the H74I variant, this cannot account for the drastic reduction of transport activity. NhlF was less affected by the H68I replacement. At a metal ion concentration of 500 nM, Ni2+ and Co2+ uptake of this variant were reduced by 60 and 90%, respectively. The inhibitory effect of the two alterations in NhlF resembled inhibition of HoxN-mediated nickel uptake by the H62I and H68I replacements (10). The results showed that TMD II of NhlF plays a central role in Ni2+ and Co2+ transport and suggested that His-68 and His-74 are directly involved in coordination of the two ions.

FIG. 1.

Activity of NhlF variants with His-to-Ile changes in a conserved region in TMD II. nhlF alleles were expressed from pCH674AF (wild type), pNhlFH68IF, and pNhlFH74IF in E. coli CC118. Wild-type hoxN was expressed from plasmid pCH675AF and served as a control. Metal accumulation during growth was analyzed in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 500 nM 63NiCl2 or 57CoCl2. The amounts of the transporters in the E. coli membrane were estimated with monoclonal anti-FLAG antibodies by Western immunoblotting.

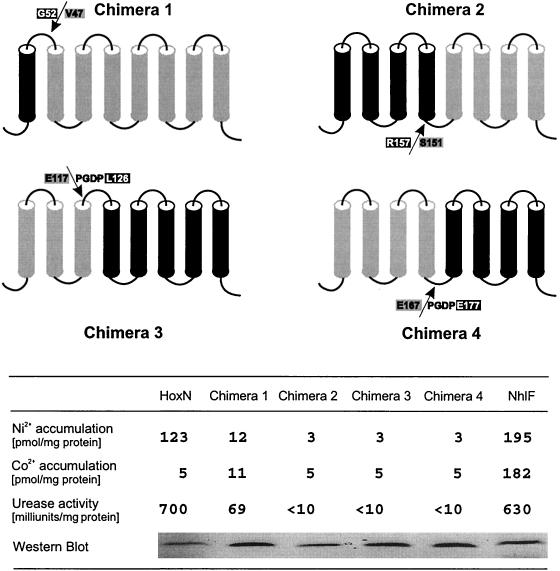

HoxN-NhlF hybrids.

HoxN (351 amino acid residues) and NhlF (352 amino acid residues) differ in their specificities for divalent ions (4, 9). To gain insight into the structural basis of the different selectivities, we constructed chimeras and analyzed these hybrids for Ni2+ and Co2+ uptake. The structures and activities of the chimeric permeases are shown in Fig. 2. The fusion sites are located in periplasmic or cytoplasmic loops. Chimera 2 contains the four amino-terminal TMDs of NhlF fused to the four carboxy-terminal TMDs of HoxN. The four amino-terminal TMDs of HoxN are fused to the four carboxy-terminal TMDs of NhlF in chimera 4. Chimera 3 consists of TMDs I to III of HoxN and TMDs IV to VIII of NhlF. Although chimeras 2, 3, and 4 were stable, none of them mediated metal ion transport in E. coli CC118 (Fig. 2). In contrast, chimera 1 showed low, but significant, transport activity. In this hybrid, TMD I of HoxN has been replaced by the respective segment of NhlF. It is evident that this modification led to a considerable reduction of Ni2+ transport. Nevertheless, production of chimera 1 in E. coli enhanced the activity of a nickel-dependent urease, demonstrating the capability of the hybrid permease to transport Ni2+ ions across the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 2). Transport properties of chimera 1 have been analyzed in more detail. The data presented in Fig. 3 confirmed that replacement of TMD I in HoxN reduced Ni2+ uptake activity. In addition, and most interestingly, they indicated that the hybrid permease, in contrast to wild-type HoxN, has the ability to transport the Co2+ ion, albeit with low activity. The very low level of Co2+ accumulation in cells expressing wild-type hoxN was also found in cells lacking a functional HoxN (not shown). It was thus considered as HoxN-independent background activity.

FIG. 2.

Structure and activity of chimeric nickel permeases. TMDs are shown as black (NhlF moiety) and grey (HoxN moiety) cylinders. The sequences at the fusion sites (arrows) in periplasmic (chimeras 1 and 3) and cytoplasmic (chimeras 2 and 4) loops are indicated in single-letter code. Construction of chimeras 3 and 4 resulted in four additional amino acid residues (PGDP) at the fusion sites. FLAG epitope-tagged chimeras 1 to 4 and parental transporters were individually produced in E. coli CC118. The metal accumulation of growing cells was assayed in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 500 nM concentrations of radiolabeled metal chlorides. The urease-enhancing activity of the permeases was analyzed in cells coexpressing a bacterial urease operon during growth in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 500 nM NiCl2. The relative quantities of the transporters were estimated by Western immunoblotting after separation of the solubilized membrane proteins by SDS-PAGE.

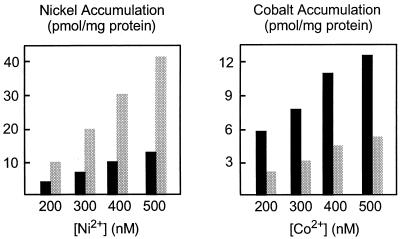

FIG. 3.

Concentration-dependent metal uptake of E. coli CC118 harboring pChi1 (black bars) or pCH675AF (grey bars). Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the radiolabeled metal chlorides at the concentrations indicated. The cellular metal content was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting.

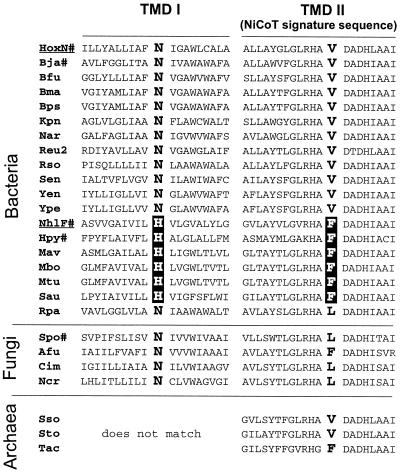

Alignment of NiCoTs points to functional interaction of TMDs I and II.

The aforementioned data suggested that the structure of TMD I, which is divergent among NiCoTs, plays an important role in selectivity. A multiple-sequence alignment of known or putative NiCoTs identified a conserved position, occupied by an Asn or His residue, in the central part of TMD I in the bacterial and fungal transporters (Fig. 4). The His is found in NiCoTs of gram-positive bacteria (including NhlF) and in NixA of H. pylori. Surprisingly, occurrence of the His residue is strictly correlated with the presence of a Phe residue in a strongly conserved segment of TMD II, the signature sequence of NiCoTs. The Asn residue in the center of TMD I is found in most bacterial NiCoTs and in the fungal NiCoTs. With the exception of the permeases of Rhodopseudomonas palustris and the fungal species, the Asn is correlated with a Val residue at the conserved position in TMD II (Fig. 4). In the R. palustris, S. pombe, Coccidioides immitis, and Neurospora crassa NiCoT sequences, the latter position is occupied by a Leu residue. The combination of Asn in TMD I and Phe in TMD II is found in the Aspergillus fumigatus sequence. The correlation of residues in TMDs I and II led us to speculate that these positions are important for a functional interaction of the two helices. The primary structures of the archaeal NiCoTs were taken from the complete genome sequences of Sulfolobus solfataricus (28), Sulfolobus tokadaii (15), and Thermoplasma acidophilum (25). These permeases contain the conserved signatures of NiCoTs, with the exception of the amino-terminal region. We were not able to precisely predict the location of TMD I for the archaeal transporters, since the overall sequence similarity in this region is low and neither an Asn nor a His is conserved.

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment of putative TMDs I and II of NiCoTs from bacteria, archaea, and fungi. The list contains experimentally investigated permeases (#), sequences from completed genome projects, and preliminary genomic and expressed sequence tag sequences. HoxN from R. eutropha and NhlF from R. rhodochrous are underlined. The correlation between an Asn or His residue in TMD I and a Val, Phe, or Leu residue within the NiCoT signature sequence in TMD II is highlighted. The similarity between TMD I of the archaeal transporters and their bacterial and fungal counterparts is not obvious. The program CLUSTALW (http://clustalw.genome.ad.jp) was used for multiple alignments. Afu, A. fumigatus; Bfu, Burkholderia fungorum; Bja, Bradyrhizobium japonicum (11); Bma, Burkholderia mallei; Bps, Burkholderia pseudomallei; Cim, C. immitis; Hpy, NixA of H. pylori (12, 13); Kpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; Mav, Mycobacterium avium; Mbo, Mycobacterium bovis; Mtu, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Ncr, N. crassa; Nar, Novosphingobium aromaticivorans; Reu2, R. eutropha; Rso, Ralstonia solanacearum; Rpa, R. palustris; Sen, Salmonella enterica; Spo, S. pombe (6); Sso, S. solfataricus; Sto, S. tokadaii; Tac, T. acidophilum; Yen, Yersinia enterocolitica; Ype, Yersinia pestis.

Role of asparagine and histidine in TMD I.

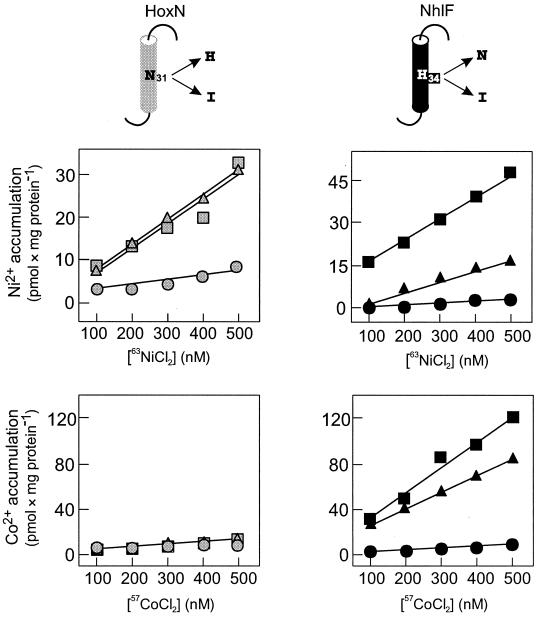

To investigate the significance of Asn-31 in HoxN and His-34 in NhlF for metal ion transport we generated hydrophobic side chains (isoleucine) in place of the polar amide- or imidazole-containing side chains. Furthermore, HoxN Asn-31 was changed to His, and the converse replacement (H34N) was introduced into NhlF. The consequences of these replacements are illustrated in Fig. 5. NhlF was completely inactivated by the hydrophobic exchange, whereas marginal transport was observed for the corresponding HoxN variant. On the other hand, the N31H mutation had no detectable effect on HoxN activity. The altered permease behaved like a high-affinity Ni2+ transporter and, like its parent, was unable to transport the Co2+ ion. The converse replacement in NhlF (H34N) had a considerable effect on Ni2+ uptake but affected Co2+ uptake only moderately. Although it is difficult to draw conclusions on kinetic parameters on the basis of our assays, it seems as if the H34N replacement in NhlF reduced the affinity for Ni2+ while slightly decreasing the velocity of Co2+ transport without affecting the affinity for this ion (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Metal accumulation of E. coli CC118 producing HoxN variants N31H and N31I (grey symbols) and NhlF variants H34N and H34I (black symbols) during growth in Luria-Bertani medium. TMD I of each of the two permeases is shown in the upper part; the approximate locations of the HoxN residue N31 and the NhlF residue H34 are indicated. Transporters were produced from plasmids pCH675A (squares), pHoxNN31H (triangles), and pHoxNN31I (circles) for HoxN and from plasmids pCH674A (squares), pNhlFH34N (triangles), and pNhlFH34I (circles) for NhlF.

A phenylalanine residue within the signature sequence of NiCoTs correlates with enhanced transport capacity.

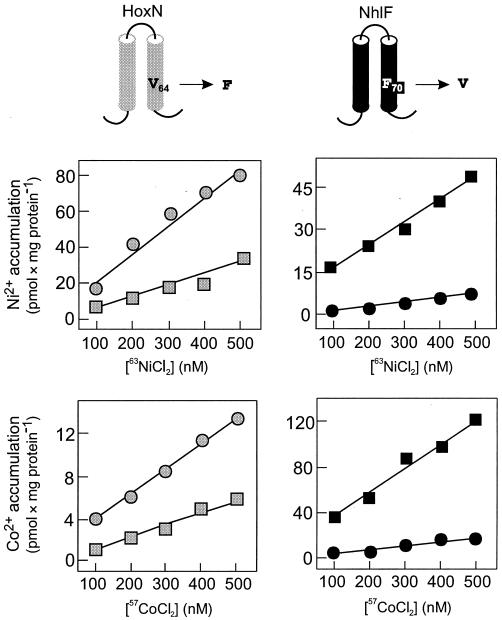

To address the question of whether the position occupied by a Val or a Phe residue in TMD II of most NiCoTs specifies selectivity, we generated the HoxN V64F and NhlF F70V derivatives. The clear-cut consequences of these alterations for metal ion transport are shown in Fig. 6. The capacity of both NhlF-mediated Ni2+ and Co2+ transport was strongly inhibited by the F70V exchange. The converse V64F replacement in HoxN raised the capacity of Ni2+ transport considerably. In addition, the bulky Phe residue at position 64 converted HoxN into a low-activity Co2+ permease. The latter observation is compatible with the notion that an increase in transport velocity resulted in a reduction of the specificity.

FIG. 6.

A bulky Phe residue within the conserved region in TMD II enhances the ion transport activity of NiCoTs. The illustrations in the upper part represent the relevant segments of HoxN and NhlF. hoxN (grey squares), hoxN V64F (grey circles), nhlF (black squares), and nhlF F70V (black circles) were expressed from plasmids pCH675A, pHoxNV64F, pCH674A, and pNhlFF70V, respectively, in E. coli CC118, and metal accumulation upon growth in Luria-Bertani medium was analyzed.

Single-residue exchanges do not interfere with stability of HoxN and NhlF.

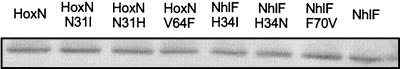

To exclude the possibility that the effects of exchanges of Asn and His (TMD I) and Val and Phe (TMD II) residues on transport activity were due to altered expression levels or reduced stability of the permeases, the content of the FLAG-tagged copies of the transporter variants in recombinant E. coli was analyzed by Western immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 7, wild-type and mutant permeases were present in comparable amounts in the membrane fraction, indicating that single-codon replacements did not interfere with stability.

FIG. 7.

Relative amounts of HoxN and NhlF variants in membranes of E. coli CC118. The mutant alleles were introduced into pCH675AF and pCH674AF, respectively, and expressed in strain CC118. Solubilized membrane proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Transporters were visualized by using monoclonal anti-FLAG antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-coupled goat anti-mouse antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Transport of transition metal ions (reviewed in reference 30) is a challenging problem for prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. These ions are found in nanomolar concentrations in standard natural environments and are essential cofactors in housekeeping and specialized metabolic processes (reviewed in reference 31). Deregulated increase of the cellular metal content, however, for instance as a consequence of uncontrolled ion uptake in metal-polluted environments, is hazardous to various cellular targets. Therefore, transition metal uptake systems must operate within a narrow range. They have to recognize metal ions with very high affinity and selectivity. On the other hand, transport with very low capacity rather than high capacity is an adaptation to cellular requirements. The latter can be achieved by strict regulation of the amounts of transporter protein in the cell or by a very low velocity of the transport process itself. In the present study we attempted to get insight into the molecular basis of selective high-affinity, low-capacity transition metal cation transport, choosing R. eutropha HoxN and R. rhodochrous NhlF for examination. The two bacterial transporters represent functional variants of the structurally related NiCoTs, a family of membrane proteins whose members are widespread in bacteria and have recently been identified in the genome sequences of certain archaeal and fungal species. HoxN is a selective Ni2+ permease and is not inhibited by Mn2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ (4). NhlF shows a preference for the Co2+ ion, transports Ni2+ with high affinity in the absence of Co2+, and is not affected by Mn2+ and Zn2+ (4). Chimeras and site-specifically altered HoxN and NhlF variants were constructed and analyzed to uncover determinants of selectivity. Replacement of His-68 and His-74 in NhlF by Ile residues affected both Co2+ and Ni2+ transport. The H68I mutant showed reduced transport of the two ions, probably due to reduced affinity, whereas the H74I mutant was completely inactive. Similar behaviors, i.e., reduction of affinity for Ni2+ and inactivation, were observed in a previous study for the corresponding mutants of HoxN (10), and thus, we conclude that (i) HoxN and NhlF employ very similar transport mechanisms and (ii) Co2+ and Ni2+ run along the same path in NhlF.

A second approach focused on the analysis of hybrid permeases. This technique has provided valuable information on the substrate recognition domains in various transporters, including human and rat catecholamine transporters (2), yeast and Chlorella monosaccharide transporters (23, 29), and E. coli aromatic amino acid transporters (3). The latter study uncovered a small region responsible for the different substrate profiles and activities of the AroP general aromatic transport system and the PheP high-affinity phenylalanine transport system, demonstrating the effectiveness of this method. Nonetheless, although AroP and PheP are 61% identical on the amino acid level, none of the AroP-PheP hybrids displayed overall transport activity above 50% of either of the parent proteins and some chimeras had lost activity completely (3). Likewise, three out of four NhlF-HoxN hybrids described in the present study, although present in amounts comparable to wild-type HoxN and NhlF in E. coli membranes, were inactive. This result could be a consequence of tertiary structure rearrangements, since many interhelical and protein-lipid contact sites might be altered in hybrid permeases. Nevertheless, the moderate activity of chimera 1 pointed to a role of TMD I in ion recognition. Komeda et al. (17) have reported that the signature VXLHVLGXAL in the central part of TMD I of NhlF is also found in TMD V of Cot1p, a transporter of the cation diffusion facilitator family in yeast vacuoles involved in the detoxification of Co2+ and Zn2+ (19, 20). They speculated that the structures of TMD I may be important for the different substrate profiles of NhlF and HoxN (17). Our data are in agreement with this hypothesis because TMD I of NhlF can confer on a selective Ni2+ permease the ability to transport Co2+ ion.

The third approach was based on multiple alignments of NiCoT sequences which identified a striking correlation between pairs of amino acid residues in TMDs I and II. Experimental topological analyses of HoxN (7, 10) and NixA (13) have localized these residues to the central parts of TMDs I and II. These findings, and the rule that transmembrane helices in membrane proteins are in spatial contact with sequence neighbors in almost every case (1), led us to assume that TMDs I and II interact to form a central part of the selectivity filter. Previous work on HoxN (10) and NixA (12) has revealed that histidine and other residues in TMD II with the potential to carry a charge are essential for Ni2+ transport. Our present results point to an important role for the Asn or His residue at a position in TMD I which is conserved in bacterial and fungal NiCoTs. Histidine is the more versatile residue and can be protonated to give a positive charge, whereas asparagine does not ionize. HoxN activity was not affected by the N31H replacement, suggesting that the Lewis base function of an unprotonated imidazole nitrogen can compensate for the amide-containing side chain. His-34 is critical for NhlF activity. As in the case of HoxN, a hydrophobic Ile residue is not tolerated at this position. Strong reduction of transport activity has also been observed for a similar variant of NixA of H. pylori (32). The H34N exchange had a slight inhibitory effect on Co2+ uptake but caused significant inhibition of Ni2+ uptake. This result is difficult to explain. It reflects the preference of wild-type NhlF for the Co2+ ion.

The results of this and a previous study (4) show that NhlF significantly and reproducibly surpasses HoxN in Ni2+ uptake activity. The higher capacity is correlated with lower specificity and could be due to weaker metal coordination in the selectivity filter, allowing faster movement of ions through the transporter. A hydrophobic residue within the NiCoT signature sequence in TMD II is a critical factor for transport capacity. This position is occupied by valine, phenylalanine, or in a few cases, leucine. The Val residue in HoxN correlates with lower activity and higher specificity than the Phe-containing NhlF. Indeed, converting Val-64 to Phe resulted in considerably increased Ni2+ uptake at various substrate concentrations and conferred to HoxN the ability to transport Co2+, although with a low capacity. Correspondingly, the F70V exchange in NhlF led to strongly decreased transport activity. These data suggest that the bulkier Phe residue hinders tight metal ion coordination, a prerequisite for extremely high selectivity.

We also constructed double mutants by conversion of the His-Phe pair in NhlF to Asn-Val and of the Asn-Val pair in HoxN to His-Phe, and we replaced the Val residue in TMD II of chimera I with Phe. However, these variants contributed little information, since all three were completely inactive (data not shown).

As shown for Kcs, a structurally well-investigated, selective K+ channel (34), it is a prerequisite for selective ion transport to remove the outer water shell of the ions and to replace inner shell water molecules with amino acid side chain and/or backbone ligands. Selective recognition of divalent transition metal cations by NiCoTs through the hydration sphere is hardly conceivable, since the ion radii and, thus, the charge densities and the volumes of the water shell are too similar. However, different preferences of the dehydrated cations for the kind and number of ligands and for the coordination type can be exploited. Octahedrally coordinated Ni2+ (83 pm) and Co2+ (79 pm in the low-spin state) have smaller radii than Cu2+ (87 pm) and Zn2+ (88 pm). In addition, the latter ions prefer lower coordination numbers, resulting in radii below 75 pm. The radius of six-coordinate low-spin Mn2+ (81 pm) is in between those of Co2+ and Ni2+, but this ion has a stronger preference than Ni2+ and Co2+ for ligands in the hard Lewis base category like O-donor moieties. Ni2+ and Co2+ are closely related metal ions. Nevertheless, HoxN is able to discriminate between the two cations and to selectively transport Ni2+. Our data have shown that interaction of TMDs I and II contributes to specificity and that replacement of a single hydrophobic residue in TMD II can interfere with capacity and specificity. The roles of other conserved features, for instance, the conserved signature in TMD III, the essential hydrophilic loop connecting TMDs IV and V, and the pairs of acidic residues in TMDs V and VI (reviewed in reference 9) for NiCoT activity need closer investigation. A very recent report on H. pylori NixA mutants assigned an essential role in nickel transport to the FX2GH sequence conserved in TMD III of NiCoTs (32).

Most of the NiCoTs have not yet been experimentally investigated, and thus, it is too soon to draw conclusions on the substrate profile of the family in its entirety. Future physiological, biochemical, and structural analyses will clarify whether or not the designation NiCoT family is appropriate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bärbel Friedrich for long-term support and Edward Schwartz for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowie, J. U. 1997. Helix packing in membrane proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 272:780-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck, K. J., and S. G. Amara. 1994. Chimeric dopamine-norepinephrine transporters delineate structural domains influencing selectivity for catecholamines and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12584-12588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgriff, A. J., G. Brasier, J. Pi, C. Dogovski, J. P. Sarsero, and A. J. Pittard. 2000. A study of AroP-PheP chimeric proteins and identification of a residue involved in tryptophan transport. J. Bacteriol. 182:2207-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degen, O., M. Kobayashi, S. Shimizu, and T. Eitinger. 1999. Selective transport of divalent cations by transition metal permeases: the Alcaligenes eutrophus HoxN and the Rhodococcus rhodochrous NhlF. Arch. Microbiol. 171:139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eitinger, T. 2001. Microbial nickel transport, p. 397-417. In G. Winkelmann (ed.), Microbial transport systems. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 6.Eitinger, T., O. Degen, U. Böhnke, and M. Müller. 2000. Nic1p, a relative of bacterial transition metal permeases in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, provides nickel ion for urease biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18029-18033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eitinger, T., and B. Friedrich. 1994. A topological model for the high-affinity nickel transporter of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Mol. Microbiol. 12:1025-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eitinger, T., and B. Friedrich. 1997. Microbial nickel transport and incorporation into hydrogenases, p. 235-256. In G. Winkelmann and C. J. Carrano (ed.), Transition metals in microbial metabolism. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 9.Eitinger, T., and M.-A. Mandrand-Berthelot. 2000. Nickel transport systems in microorganisms. Arch. Microbiol. 173:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eitinger, T., L. Wolfram, O. Degen, and C. Anthon. 1997. A Ni2+ binding motif is the basis of high-affinity nickel transport of the Alcaligenes eutrophus nickel permease. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17139-17144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu, C., S. Javedan, F. Moshiri, and R. J. Maier. 1994. Bacterial genes involved in incorporation of nickel ion into a hydrogenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5099-5103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulkerson, J. F., Jr., R. M. Garner, and H. L. T. Mobley. 1998. Conserved motifs and residues in the NixA protein of Helicobacter pylori are critical for the high affinity transport of nickel ions. J. Biol. Chem. 273:235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulkerson, J. F., Jr., and H. L. T. Mobley. 2000. Membrane topology of the NixA nickel transporter of Helicobacter pylori: two nickel transport-specific motifs within transmembrane helices II and III. J. Bacteriol. 182:1722-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausinger, R. P. 1993. Biochemistry of nickel. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y.

- 15.Kawarabayashi, Y., Y. Hino, H. Horikawa, K. Jin-No, M. Takahashi, M. Sekine, S. Baba, A. Ankai, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, S. Fukui, Y. Nagai, K. Nishijima, R. Otsuka, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, Y. Kato, T. Yoshizawa, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, S. Masuda, M. Yanagii, M. Nishimura, A. Yamagishi, T. Oshima, and H. Kikuchi. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon, Sulfolobus tokadaii strain 7. DNA Res. 8:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi, M., and S. Shimizu. 1999. Cobalt proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 261:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komeda, H., M. Kobayashi, and S. Shimizu. 1997. A novel transporter involved in cobalt uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:36-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, L., and J. Kaplan. 1998. Defects in the yeast high affinity iron transport system result in increased metal sensitivity because of the increased expression of transporters with broad transition metal specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22181-22187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDiarmid, C. W., L. A. Gaither, and D. Eide. 2000. Zinc transporters that regulate vacuolar zinc storage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19:2845-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manoil, C., and J. Beckwith. 1985. TnphoA: a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:8129-8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulrooney, S. B., H. S. Pankratz, and R. P. Hausinger. 1989. Regulation of gene expression and cellular localization of cloned Klebsiella aerogenes (K. pneumoniae) urease. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:1769-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishizawa, K., E. Shimoda, and M. Kasahara. 1995. Substrate recognition domain of the Gal2 galactose transporter in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as revealed by chimeric galactose-glucose transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 270:2423-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson, G. L. 1977. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal. Biochem. 83:346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruepp, A., W. Graml, M.-L. Santos-Martinez, K. K. Koretke, C. Volker, H. W. Mewes, D. Frishman, S. Stocker, A. N. Lupas, and W. Baumeister. 2000. The genome sequence of the thermoacidophilic scavenger Thermoplasma acidophilum. Nature 407:508-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saier, M. H., Jr. 2000. A functional-phylogenetic classification system for transmembrane solute transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:354-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saier, M. H., Jr. 2001. Families of transporters: a phylogenetic overview, p. 1-22. In G. Winkelmann (ed.), Microbial transport systems. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 28.She, Q., R. K. Singh, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, G. Allard, M. J. Awayez, C. C.-Y. Chan-Weiher, I. G. Clausen, B. A. Curtis, A. De Moors, G. Erauso, C. Fletcher, P. M. K. Gordon, I. Heikamp-de Jong, A. C. Jeffries, C. J. Kozera, N. Medina, X. Peng, H. P. Thi-Ngoc, P. Redder, M. E. Schenk, C. Theriault, N. Tolstrup, R. L. Charlebois, W. F. Doolittle, M. Duguet, T. Gaasterland, R. A. Garret, M. A. Ragan, C. W. Sensen, and J. Van der Ost. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Will, A., R. Grassl, J. Erdmenger, T. Caspari, and W. Tanner. 1998. Alteration of substrate affinities and specificities of the Chlorella Hexose/H+ symporters by mutations and construction of chimeras. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11456-11462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkelmann, G. (ed.). 2001. Microbial transport systems. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 31.Winkelmann, G., and C. J. Carrano (ed.). 1997. Transition metals in microbial metabolism. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 32.Wolfram, L., and P. Bauerfeind. 2002. Conserved low-affinity nickel-binding amino acids are essential for the function of the nickel permease NixA of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:1438-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfram, L., B. Friedrich, and T. Eitinger. 1995. The Alcaligenes eutrophus protein HoxN mediates nickel transport in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:1840-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou, Y., J. H. Morais-Cabral, A. Kaufman, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 Å resolution. Nature 414:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]