Abstract

Objective

Youth processed in the juvenile justice system are at great risk for early violent death. Groups at greatest risk, ie, racial/ethnic minorities, male youth, and urban youth, are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. We compared mortality rates for delinquent youth with those for the general population, controlling for differences in gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Methods

This prospective longitudinal study examined mortality rates among 1829 youth (1172 male and 657 female) enrolled in the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a study of health needs and outcomes of delinquent youth. Participants, 10 to 18 years of age, were sampled randomly from intake at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in Chicago, Illinois, between 1995 and 1998. The sample was stratified according to gender, race/ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, or other), age (10–13 or ≥14 years), and legal status (processed as a juvenile or as an adult), to obtain enough participants for examination of key subgroups. The sample included 1005 African American (54.9%), 296 non-Hispanic white (16.2%), 524 Hispanic (28.17%), and 4 other-race/ethnicity (0.2%) subjects. The mean age at enrollment was 14.9 years (median age: 15 years). The refusal rate was 4.2%. As of March 31, 2004, we had monitored participants for 0.5 to 8.4 years (mean: 7.1 years; median: 7.2 years; interquartile range: 6.5–7.8 years); the aggregate exposure for all participants was 12 944 person-years. Data on deaths and causes of death were obtained from family reports or records and were then verified by the local medical examiner or the National Death Index. For comparisons of mortality rates for delinquents and the general population, all data were weighted according to the racial/ethnic, gender, and age characteristics of the detention center; these weighted standardized populations were used to calculate reported percentages and mortality ratios. We calculated mortality ratios by comparing our sample’s mortality rates with those for the general population of Cook County, controlling for differences in gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Results

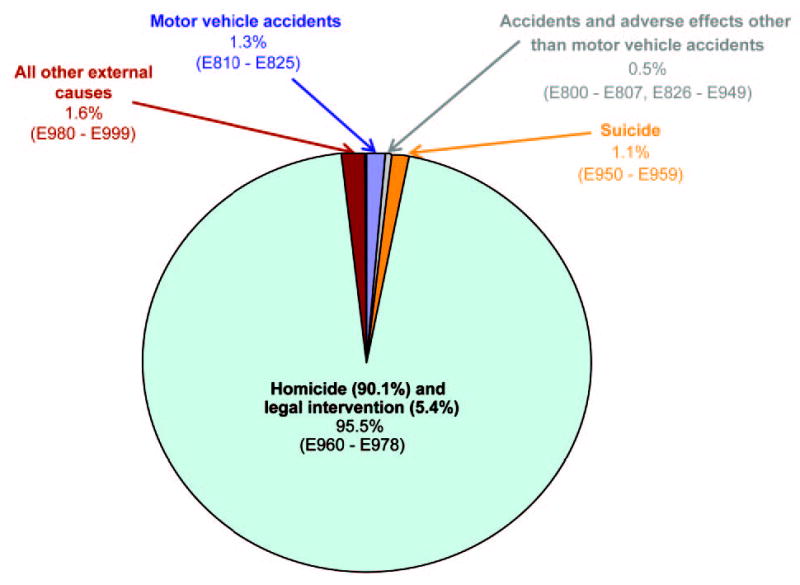

Sixty-five youth died during the follow-up period. All deaths were from external causes. As determined by using the weighted percentages to estimate causes of death, 95.5% of deaths were homicides or legal interventions (90.1% homicides and 5.4% legal interventions), 1.1% of all deaths were suicides, 1.3% were from motor vehicle accidents, 0.5% were from other accidents, and 1.6% were from other external causes. Among homicides, 93.0% were from gunshot wounds. The overall mortality rate was >4 times the general-population rate. The mortality rate among female youth was nearly 8 times the general-population rate. African American male youth had the highest mortality rate (887 deaths per 100 000 person-years).

Conclusions

Early violent death among delinquent and general-population youth affects racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately and should be addressed as are other health disparities. Future studies should identify the most promising modifiable risk factors and preventive interventions, explore the causes of death among delinquent female youth, and examine whether minority youth express suicidal intent by putting themselves at risk for homicide.

Keywords: juvenile, delinquent, death, homicide, detainees, gun violence, mortality

ABBREVIATIONS: CI, confidence interval; CIBS, bootstrap confidence interval

Delinquent youth, who often are depicted as juvenile predators,1 are also at great risk for injury2–5 and early violent death.6,7 Offending increases exposure to life-threatening situations.4,8,9 In their classic study of 500 white male delinquents sampled in the 1940s, Glueck and Glueck10 found that nearly 5% had died by age 32, compared with 2.2% of nondelinquent control subjects; by age 65, 13% had died unnatural deaths, compared with 6% of the nondelinquent control subjects.5 Another study of 118 delinquents found that 7 (5.9%) had died by age 25.6 Similarly, death rates in 2 samples of male parolees were 3.6% (1998 male subjects sampled in 1981–1982 and tracked for 6 years) and 5.5% (1997 male subjects sampled in 1986–1987 and tracked for 11 years).7

Previous studies do not reflect today’s delinquent youth. The Glueck and Glueck study5,10 in the 1940s did not include racial/ethnic minorities (now nearly two thirds of juvenile detainees11) and, like the study by Lattimore et al,7 did not include female youth (now 28% of arrested youth12 and 13% of youth in residential placement11). Even studies that included female youth6 had too few for analysis of gender differences. Finally, the most recent US study was conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s,7 when youth homicides were increasing to record high levels.13

Studying mortality rates among delinquent youth is timely. Homicide, the second leading cause of death for youth 15 to 24 years of age (5219 homicides in 2002),14 is the only major cause of childhood death to increase in incidence in the past 30 years.15 Data published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that, among African American youth, homicide is the most common cause of death (48.3 deaths per 100 000 person-years).16 African American youth’s annual rate of homicide is 2.7 times that of Hispanic youth (17.7 deaths per 100 000 person-years) and 13 times that of non-Hispanic white youth (3.7 deaths per 100 000 person-years).16 Groups at greatest risk (ie, racial/ethnic minorities, male youth, and urban youth) are all overrepresented in the juvenile justice system.17,18 In this report, we contrast the standardized annual mortality rates for a sample of delinquent youth, ie, youth processed in the juvenile justice system, with that for a comparable sample of general-population youth.

METHODS

This research was approved by the Northwestern University and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention institutional review boards and by the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Human Research Protections. We obtained informed consent from all participants ≥18 years of age. For participants <18 years of age, we obtained assent from the youth and consent from a parent or guardian, whenever possible; when this was not possible, youth assent was overseen by a participant advocate representing the interests of the youth.

Participants were 1829 youth (1172 male and 657 female) who were enrolled between 1995 and 1998 in the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a longitudinal study of health needs and outcomes of delinquent youth. Participants, who were then 10 to 18 years of age, were sampled randomly from intake at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (Chicago, IL). The sample was stratified according to gender, race/ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, or other), age (10–13 or ≥14 years), and legal status (processed as a juvenile or as an adult), to obtain enough participants to examine key subgroups, eg, female youth, Hispanic youth, and younger adolescents. Table 1 reports the sample’s demographic characteristics. The sample included 1172 male youth (64.1%) and 657 female youth (35.9%), 1005 African American (54.9%), 296 non-Hispanic white (16.2%), 524 Hispanic (28.7%), and 4 of other race/ethnicity (0.2%). The mean age of participants was 14.9 years, and the median age was 15 years. Additional information is available elsewhere.19–21

TABLE 1.

Unweighted Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | n (N = 1829) | % of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 1005 | 54.9 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 296 | 16.2 |

| Hispanic | 524 | 28.7 |

| Other | 4 | 0.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1172 | 64.1 |

| Female | 657 | 35.9 |

| Age, y | ||

| Mean | 14.9 | |

| Median | 15 | |

| Mode | 16 | |

| Specific ages, y | ||

| 10 | 7 | 0.4 |

| 11 | 20 | 1.1 |

| 12 | 87 | 4.8 |

| 13 | 258 | 14.1 |

| 14 | 217 | 11.9 |

| 15 | 498 | 27.2 |

| 16 | 644 | 35.2 |

| 17 | 89 | 4.9 |

| 18 | 9 | 0.5 |

| Education | ||

| ≤6th grade | 89 | 4.9 |

| 7th grade | 171 | 9.3 |

| 8th grade | 306 | 16.7 |

| 9th grade | 568 | 31.1 |

| 10th grade | 455 | 24.9 |

| 11th grade | 172 | 9.4 |

| 12th grade | 27 | 1.5 |

| Currently in GED classes | 31 | 1.7 |

| Alternative or home schooling | 5 | 0.3 |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.3 |

| Legal status | ||

| Processed in adult court (automatic transfer) | 275 | 15.0 |

| Processed in juvenile court | 1554 | 85.0 |

Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding errors.

We have been tracking our participants since they were enrolled in the study. To ensure comparability with other studies of mortality rates,22,23 we examined deaths that occurred between 15 and 24 years of age. As of March 31, 2004, we had monitored participants for 0.5 to 8.4 years (mean: 7.1 years; median: 7.2 years; interquartile range: 6.5–7.8 years); the aggregate exposure for all participants was 12 944 person-years.

Deaths were identified during contacts with participants’ friends, family members, and other acquaintances, by checking death records at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s office, and by submitting our participants’ names to the National Death Index.24 We verified all deaths by obtaining copies of death certificates.

Our comparison group included all persons in the general population of Cook County, Illinois, who were 15 to 24 years of age.25 We obtained counts of deaths in the comparison group by using the most recent source available, the National Center for Health Statistics Multiple Cause-of-Death Public Use Files for 1996–2001.26 To compare mortality rates for delinquents and the general population, all data were weighted according to the racial/ethnic, gender, and age characteristics of the detention center; these weighted standardized populations were used to calculate reported percentages and mortality ratios. We calculated mortality ratios by comparing our sample’s mortality rate with that for the general population of Cook County, controlling for differences in gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

We used nonparametric bootstrap methods (with 5000 replications and bias correction) for all tests of inference. These methods are widely applicable and, for rare events such as death, they provide unbiased tests of inference.27 We report 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIBS).

RESULTS

Sixty-five participants died during the follow-up period. Table 2 reports their gender, race/ethnicity, and age. Figure 1 shows that all died as a result of external causes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision,28 codes E800–E999); 95.5% died as a result of homicide or legal intervention (90.1% homicide and 5.4% legal intervention), and 1.1% of all deaths were suicides. Among homicides, 93.0% were from gunshot wounds.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of Deaths in the Sample of Delinquent Youth (N = 1829)

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Male (n = 1172) | 51 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American (n = 575) | 23 |

| Non-Hispanic white (n = 207) | 7 |

| Hispanic (n = 387) | 21 |

| Other (n = 3) | 0 |

| Age of death | |

| 15–16 y | 8 |

| 17–18 y | 21 |

| 19–20 y | 14 |

| ≥21 y | 8 |

| Female (n = 657) | 14 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American (n = 430) | 7 |

| Non-Hispanic white (n = 89) | 2 |

| Hispanic (n = 137) | 5 |

| Other (n = 1) | 0 |

| Age of death | |

| 15–16 y | 1 |

| 17–18 y | 3 |

| 19–20 y | 5 |

| ≥21 y | 5 |

| Total (n = 1829) | 65 |

Fig 1.

Causes of death for delinquent youth (with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision,28 codes). Percentages were weighted according to the racial/ethnic, gender, and age characteristics of the detention center.

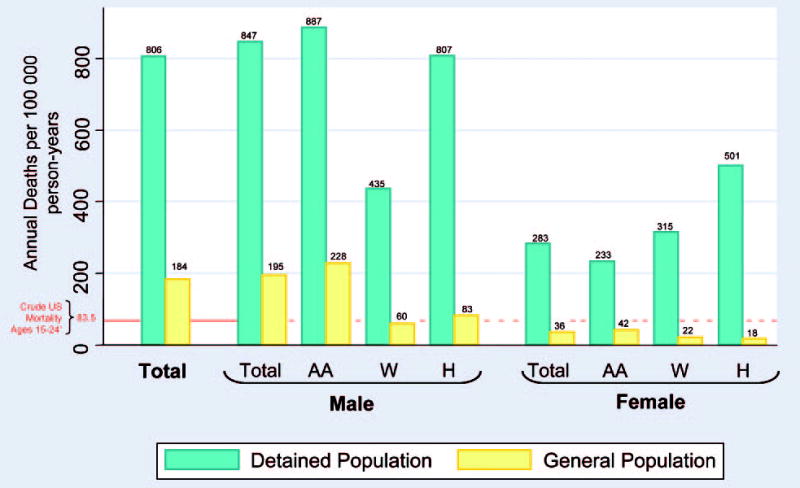

Next, we compared the mortality rate from external causes among delinquents with that for the general population, controlling for gender and race/ethnicity. Figure 2 and Table 3 present standardized annual mortality rates per 100 000 person-years for our sample of delinquent youth and the general population, with 95% confidence intervals (CIBS), and standardized mortality ratios comparing our sample with the general population, with 95% CIs. For reference, Fig 2 also shows the crude mortality rate for 1996–2001 for the same age group (15–24 years of age) in the general population (not corrected for gender, race/ethnicity, and age).29–34

Fig 2.

Standardized rates of death attributable to external causes for delinquent and community youth. AA indicates African American; W, non-Hispanic white; H, Hispanic. The crude mortality rate for 1996–2001 was computed from the National Center for Health Statistics reports.29–34

TABLE 3.

Standardized Rates of Death Attributable to External Causes for Delinquent and Community Youth, Mortality Ratios, and 95% CIs

| Mortality Rate, Deaths per 100 000 Person-Years (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Detained Population | Community Population | Mortality Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Total | 806 (520–1172) | 184 (177–190) | 4.4* (2.8–6.4) |

| Male | 847 (539–1242) | 195 (188–203) | 4.3* (2.8–6.4) |

| African American | 887 (505–1379) | 228 (217–239) | 3.9† (2.2–6.1) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 435 (142–823) | 60 (54–66) | 7.3‡ (2.4–13.8) |

| Hispanic | 807 (466–1234) | 83 (76–91) | 9.8* (5.6–15.1) |

| Female | 283 (154–457) | 36 (32–40) | 7.9* (4.3–13.0) |

| African American | 233 (45–442) | 42 (36–165) | 5.5§ (0.8–10.7) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 315 (0–892) | 22 (19–332) | 14.1§ (0.0–40.4) |

| Hispanic | 501 (18–1026) | 18 (0–22) | 28.5‡ (5.2–60.8) |

Significant at P < .001.

Significant at P < .01.

Significant at P < .05.

Not significant at .05.

The standardized mortality rate for delinquent youth (806 deaths per 100 000 person-years) was >4 times that for general-population youth (184 deaths per 100 000 person-years; mortality ratio: 4.4; 95% CIBS: 2.8–6.4). Table 3 also shows that mortality ratios were significantly >1 for male youth overall, for each racial/ethnic subgroup of male youth, for female youth overall, and for Hispanic female youth. The CIBS was quite wide for Hispanic female youth (mortality ratio: 28.5; 95% CIBS: 5.2–60.8), which suggests instability in the size of this mortality ratio. Both delinquent and general-population female youth had significantly lower mortality rates than did their male counterparts.

Delinquent African American male youth had the highest mortality rate (887 deaths per 100 000 person-years; 95% CIBS: 505–1379 deaths per 100 000 person-years). However, African American male youth had the lowest mortality ratio (3.9; 95% CIBS: 2.2–6.1) because the mortality rate for the general population was relatively high (228 deaths per 100 000 person-years; 95% CIBS: 217–239 deaths per 100 000 person-years). Tests for differences in mortality rates among racial/ethnic groups were not significant for either male or female youth, possibly because there were too few participants within racial/ethnic subgroups for detection of differences.

DISCUSSION

Mortality Rates

Overall, the mortality rate among delinquent youth was >4 times higher than that in the standardized general population of Cook County. Of particular concern was the mortality rate for delinquent female youth, which was nearly 8 times the general-population rate. More than 90% of deaths among delinquent youth were homicides. More than 90% of deaths were from gunshot wounds, either homicidal, accidental, or self-inflicted. To put our findings (806 deaths per 100 000 person-years) into perspective, the leading causes of death among youth in the general population are accidents (38.0 deaths per 100 000 person-years), homicide (12.9 deaths per 100 000 person-years), suicide (9.9 deaths per 100 000 person-years), and malignant neoplasms (4.3 deaths per 100 000 person years).35

Mortality rates in this sample appeared to be as much as 3 times greater than those among delinquents, 11 to 32 years of age, in the 1940s study by Glueck and Glueck,10 who examined only non-Hispanic white male youth. Mortality rates in our sample also appeared to be higher than those reported by Lattimore et al,7 although their study included only male youth and was conducted when homicide rates were at an all-time high.13 It is sobering that the findings of Laub and Vaillant5 suggest that, as delinquent youth age, they continue to have greater mortality rates than the general population.

The overall mortality rate in our sample was similar to that in a recent Australian study of young offenders.36 However, nearly one half of the Australian sample’s deaths were attributable to drug overdoses, compared with only 3 deaths in our sample. The paucity of drug overdoses in our sample might be because few of our participants used illegal drugs other than marijuana or alcohol.37,38 Nevertheless, many of the homicides in our sample might be drug related; nearly 97% of youth who died as a result of homicide had sold drugs, an activity fraught with risk.39

Our findings highlight several key public health issues. Even in the US general population, homicides are not uncommon among youth. Although homicide rates have decreased since the early 1990s, homicides still represent 15.8% of all deaths among youth.16 More than one third of homicide deaths in 2002 involved persons <25 years of age.35 On an average day in the year 2000, 3.56 youth <18 years of age became victims of homicide.17 Homicide rates for our sample were more than double those among male youth 15 to 24 years of age in Cali, Columbia.40,41

Our findings highlight the role of firearms in early violent deaths, especially homicides. Among youth 15 to 24 years of age in the United States, 20% of deaths are from firearms35; in our sample, >90% of deaths were from firearms. In the United States, nearly 80% of homicides among youth are related to firearms.14 Nationally, only motor vehicle accidents cause more deaths than guns among youth 15 to 24 years of age.42

Deaths from firearms affect minority youth disproportionately, both in this sample and in the US general population.33 Of youth (15–24 years of age) killed by firearms in the US general population in 2000, 60.6% were African American or Hispanic,33 compared with almost 98% in this sample. Among African American and Hispanic youth (15–24 years of age) in the US general population who died in 2000, 34% of deaths were firearm related,33 compared with >90% in our sample. Although homicide rates are decreasing among all racial/ethnic groups and ages, these decreases have not been as dramatic among African American youth.13

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Like previous studies,5,7 we sampled from a detained population. Generalizability is limited to urban youth who are apprehended and detained. Detained youth may engage in more serious delinquent acts than arrestees or youth whose delinquency is not detected.

Because death is relatively rare, even with a large sample, some CIs were wide. Moreover, we could not examine well-known correlates of early violent death, eg, gang affiliation,7 substance abuse,43 family disorganization,5,44 and child physical abuse.45

The available general population data (1996–2001) are not precisely contemporaneous with deaths in our sample (June 1996 through March 2003). Bias is minimal, however, because homicide rates in the general population have not changed appreciably since 2001 (refs 12 and 13; M. Sickmund, PhD, verbal communication, 2005).

The true mortality ratios may be even greater than those observed, for 3 reasons. (1) Because we counted death only when we could obtain a death certificate, we might have underestimated the true mortality rate for our sample. (2) Our groups, ie, the sample and the standardized general population of Cook County, are not mutually exclusive, because the comparison group (the general population) also includes youth who have been detained. (3) Census data (the denominator with which risk is computed for the general population) undercount male subjects, minorities, youth, and persons living in central cities,46,47 increasing estimates of mortality rates for these groups and decreasing the mortality ratio. Overall, these limitations attenuate the differences between the sample and the comparison group and reduce the power to detect them. Conversely, the true mortality ratios may be smaller than observed, because 1.2% of deaths reported to the National Death Index do not list the cause of death.26 Despite these limitations, our study has implications for research and for public health policy.

Future Research

Longitudinal Studies of Violent Victimization

Longitudinal descriptive studies would provide information about resilience to violent victimization in high-risk groups, risk factors in low-risk groups, and the most promising modifiable risk factors. Longitudinal intervention studies could inform public health professionals about the effectiveness and persistence of prevention strategies, which programs warrant investment, for which risk groups, and whether gender-specific and culturally specific interventions warrant the additional effort. We especially need studies of youth as they make the transition from adolescence into young adulthood, the period of greatest risk.

Studies of Delinquent Female Youth

Despite the relatively small numbers of female youth in the juvenile justice system (28% of arrested youth but growing12), research on female youth is especially needed. Compared with delinquent male youth, female youth are more likely to have histories of physical and sexual abuse and certain psychiatric disorders.19–21,48 Intimate partner violence and pregnancy-associated homicide are particularly important areas to study.49–51 Two female subjects died during domestic disputes. Even in the general population, female youth (≤24 years of age) are 10 times more likely than male youth to be killed by intimate partners.52

Suicidal Ideation and Risk Among Minority Youth

Suicide is now the third leading cause of death among African American youth 15 to 19 years of age.16 The rate increased from 2.1 deaths per 100 000 person-years in 1980 (10–19 years of age) to 4.5 deaths per 100 000 person-years in 1995,53 and suicide is now nearly as common among minority youth as among nonminority youth.54 In our sample, African American male youth had a significantly higher mortality rate than other groups; however, no deaths were recorded officially as suicide. The true suicide rate among minority youth may be much higher than indicated by our findings. Some studies54–56 suggested that African American youth may express suicidal intent by putting themselves at risk for homicide. Additional research is needed to examine the many ways suicidality manifests as violent death among minority youth.

Implications for Public Health Policy

The Surgeon General’s goal is to reduce homicides (among youth and adults) from 6.5 deaths per 100 000 person-years in 1998 to ≤3.0 deaths per 100 000 person-years by the year 2010.57 Medical, public health, and juvenile justice professionals must take the following steps.

First, early violent death should be addressed as aggressively as any other health disparity. Compared with non-Hispanic white youth, minority youth have a much greater risk of early violent death. Moreover, minorities are overrepresented in the justice systems. One study found that more than one fourth of low-income, urban, African American youth have been arrested by age 18.58 More than 1 in 10 African American males in their 20s and early 30s are incarcerated at any given time, compared with 4% of Hispanic and 1.6% of non-Hispanic white males.59

Second, delinquency and violence prevention programs should be implemented. Attempts to reduce violence can begin by addressing common modifiable risk factors, such as physical fighting (reported by 33% of general-population youth in grades 9 through 1260), carrying weapons (17.1% of youth60), and gang membership (reported by 10.6% of eighth graders61). Delinquency prevention could reduce the proclivity of offenders to become victims.3,8 Interventions must be tailored to youth of widely varying social, economic, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds62 and should include parent training, mentoring, home visitation, and education.62

Third, violence-prevention interventions should be implemented in nontraditional settings. School-based interventions should be augmented with community-based programs. Public health, criminal justice, and educational experts must collaborate to develop interventions in nontraditional settings for youth who do not attend school regularly. For example, interventions in urban detention centers would reach youth at the greatest risk: male youth, racial/ethnic minority youth, older teens, and urban youth. Moreover, they would reach high-risk youth who cycle through the juvenile justice system at some time during their adolescence.19,20 Referrals from juvenile courts to violence prevention programs could reach as many as 1.1 million youth per year18,63 who are processed through the juvenile justice system.

Fourth, US firearms policies should be evaluated in terms of the national public health. In 2002, 30 242 persons of all ages died from firearms in the United States.35 Nearly one fourth of victims are youth 15 to 24 years of age.35 A World Health Organization report on violence and health64 showed that the rate of death from firearms in the United States is >3 times greater than that in Canada, >6 times greater than that in Australia, and nearly 38 times greater than that in the United Kingdom. Although the consequences of gun violence in our society are incalculable, the financial costs are well documented.65 The costs to society attributable to gun violence against youth are estimated at $15 billion per year.66

Fifth, conditions correlated with early violent death should be improved. Many detained youth are poor.67–69 Since the 1970s, income segregation (in addition to racial/ethnic segregation) has resulted in increased concentration of poverty in US cities.70 Reducing poverty, segregation, and de facto racial/ethnic isolation, which are known correlates of illness, violence, death, and homicide, could also reduce violence among youth.71

Sixth, mental health services for high-risk youth should be improved. Nearly three fourths of detained female youth and two thirds of detained male youth have ≥1 psychiatric disorder.19,21 The Surgeon General reports that, despite their need for mental health treatment, insufficient services are available for delinquent youth in detention centers or after they return to their communities.72 Treating youth who have behavioral or substance use disorders may reduce the risk of victimization by curtailing the high-risk lifestyles associated with these disorders.73 Moreover, treating youth who have substance use or mood disorders may decrease suicidal risk.74

CONCLUSIONS

Perhaps nothing underscores our failure to reach and rehabilitate at-risk youth more than their vulnerability to an early violent death. Ironically, mass school shootings (52 deaths between 1990 and 200075) have received far more attention than homicides of inner-city youth, which, in New York City alone, accounted for 840 deaths of youth 14 to 17 years of age.76 School shootings capture the nation’s attention because of their rarity, drama, and potential for contagion.75,77 Although urban violence may no longer be viewed as newsworthy,78 the health professions must address the equally tragic, if less dramatic, daily violence that affects urban delinquent youth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH54197 and R01MH59463 and Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention grant 1999-JE-FX-1001. Major funding was also provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Princeton, NJ), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD), the Center for Mental Health Services (Rockville, MD), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention (Atlanta, GA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center on Injury Prevention and Control (Atlanta, GA), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Bethesda, MD), the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (Rockville, MD), the National Institutes of Health Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Bethesda, MD), the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (Rockville, MD), the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health (Bethesda, MD), the National Institutes of Health Office of Rare Diseases (Bethesda), and the William T. Grant Foundation (New York, NY). Additional funds were provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (Chicago, IL), the Open Society Institute (New York, NY), and the Chicago Community Trust. We thank all of our agencies for their collaborative spirit and steadfast support. These study sponsors played no role in the design, methods, data management, or analysis of this project or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Many people contributed to this project. Ann Hohmann, PhD, and Kimberly Hoagwood, PhD, provided technical support in the design; Heather Ringeisen, PhD, provided helpful advice; Grayson Norquist, MD, and Delores Parron, PhD, provided steadfast support throughout. We thank Katherine Christoffel, MD, Anthony Komaroff, MD, Mary McFarlane, PhD, Kiang Liu, PhD, and the anonymous reviewers for insightful critiques of prior drafts. We thank all project staff members, especially Amy M. Lansing, PhD, for supervising the data collection. Laura Coats performed outstanding library work and editing. We thank the Cook County Office of the Medical Examiner, headed by Edmund Donoghue, MD, and the late Mary Kehoe Griffin. We also appreciate greatly the cooperation of everyone working in the Cook County systems, especially David H. Lux, our project liaison. Without the county’s cooperation, this study would not have been possible. Finally, we thank our participants and their families for their time and willingness to take part. We extend our sympathies to the families and loved ones of youth who died.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Mileusnic’s current address is: Knox County Office of the Medical Examiner, Knoxville, TN 37920.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Mental Health; 2001

- 2.Lauritsen JL, Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Conventional and delinquent activities: implications for the prevention of violent victimization among adolescents. Violence Vict. 1992;7:91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeber R, Kalb L, Huizinga D. Juvenile Delinquency and Serious Injury Victimization. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2001. Publication NCJ 188676

- 4.Menard S. Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Adolescent Victimization. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2002. Publication NCJ 191210

- 5.Laub JH, Vaillant GE. Delinquency and mortality: a 50-year follow-up study of 1,000 delinquent and nondelinquent boys. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:96–102. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeager CA, Lewis DO. Mortality in a group of formerly incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:612–614. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lattimore PK, Linster RL, MacDonald JM. Risk of death among serious young offenders. J Res Crime Delinq. 1997;34:187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeber R, DeLamatre M, Tita G, Cohen J, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Gun injury and mortality: the delinquent backgrounds of juvenile victims. Violence Vict. 1999;14:339–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huizinga D, Jakob-Chien C. The contemporaneous co-occurrence of serious and violent juvenile offending and other problem behaviors. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, eds. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998:47–67

- 10.Glueck S, Glueck E. Unravelling Juvenile Delinquency New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 1950

- 11.Sickmund M, Wan Y. Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement Data-book. Available at: www.ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/cjrp Accessed March 26, 2002

- 12.Snyder HN. Juvenile Arrests 2001. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. Publication NCJ 201370

- 13.Fox JA, Zawitz MW. Homicide Trends in the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2002. Publication NCJ 173956

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten Leading Causes of Death, United States. Available at: http://cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars Accessed April 4, 2005

- 15.Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Homicides of Children and Youth Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2001. Publication NCJ 187239

- 16.Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;53(17):1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastore AL, Maguire K. Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2001 Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2002

- 18.Snyder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 1999 National Report Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999

- 19.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:906–912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1097–1108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh GK, Yu SM. Trends and differentials in adolescent and young adult mortality in the United States, 1950 through 1993. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:560–564. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Statistics of the United States, 1992, Vol II, Mortality, Part A Washington, DC: US Public Health Service; 1996

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Death Index. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/r&d/ndi/what_is_ndi.htm Accessed June 9, 2003

- 25.US Bureau of the Census. Special Tabulations Program. Available at: www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/sptabs/main.html Accessed December 31, 2001

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death Public Use Files for 1996–2001 [book on CD-ROM]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. National Technical Information Services Publication PB2000-500128

- 27.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1993

- 28.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1977

- 29.Peters KD, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1996. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1998;47(9):1–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyert DL, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1997. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1999;47(19):1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2000;48(11):1–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoyert DL, Arias E, Smith BL, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 1999. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(8):1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minino AM, Arias E, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Smith BL. Deaths: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002;50(15):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arias E, Anderson RN, Kung H-C, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003;52(3):1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Anderson RN, Scott C. Deaths: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004;53(5):119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coffey C, Veit F, Wolfe R, Cini E, Patton GC. Mortality in young offenders: retrospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2003;326:1064–1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7398.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClelland GM, Elkington KS, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Multiple substance use disorders in juvenile detainees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1215–1224. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000134489.58054.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Detection and Prevalence of Substance Use Among Juvenile Detainees Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2004. Publication NCJ 203934

- 39.Howell JC, Decker SH. The Youth Gangs, Drugs and Violence Connection. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. Publication NCJ 171152

- 40.Villaveces A, Cummings P, Espitia VE, Koespsell TD, McKnight B, Kellermann AL. Effect of a ban on carrying firearms on homicide rates in 2 Colombian cities. JAMA. 2000;283:1205–1209. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patterns of homicide: Cali, Columbia, 1993–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:734–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2000 Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2001

- 43.Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates of aggressive and violent behavior among public high school adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:26–34. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)94070-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caputo RK. Correlates of mortality in a U.S. cohort of youth, 1980–98: implications for social justice. Soc Justice Res. 2002;15:271–293. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabotta EE, Davis RL. Fatality after report to a child abuse registry in Washington State 1973–1986. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:627–635. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90101-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson JG. ESCAP II: Demographic Analysis Results: Executive Steering Committee for A.C.E. Policy 11 Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2001

- 47.Schenker N, Bell WR, Fay RE, et al. Undercount in the 1990 Census. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88:1044–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:403–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR. Domestic violence against women: incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA. 1995;273:1763–1767. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.22.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:471–477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenfeld LA, Rand MR, Craven D, et al. Violence by Intimates. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 1998. Publication NCJ 167237

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide among black youths: United States, 1980–1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, Shaffer D. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:386–405. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046821.95464.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poussaint AF, Alexander A. Lay My Burden Down: Unraveling Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African Americans Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2000

- 56.Joe S, Kaplan MS. Suicide among African American men. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:106–121. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.106.24223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2000

- 58.Reynolds AJ. Resilience among black urban youth: prevalence, intervention effects, and mechanisms of influence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:84–100. doi: 10.1037/h0080273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harrison PM, Karberg JC. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2002 Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2003. Publication NCJ 198877

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence-related behaviors among high school students—United States, 1991–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:651–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esbensen FA, Deschenes EP. A multisite examination of youth gang membership: does gender matter? Criminology. 1998;36:799–827. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton TN, Craft CA, Dahlberg LL, Lynch BS, Baer K. Best Practices of Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action (Revised). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2002

- 63.Puzzanchera C, Stahl AL, Finnegan TA, Tierney N, Snyder HN. Juvenile Court Statistics 1999 Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice; 2003

- 64.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World Report on Violence and Health Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002

- 65.Kizer KW, Vassar MJ, Harry RL, Layton KD. Hospitalization charges, costs, and income for firearm-related injuries at a university trauma center. JAMA. 1995;273:1768–1773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cook PJ, Ludwig J. The costs of gun violence against children. Future Child. 2002;12:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCabe KM, Lansing AE, Garland A, Hough R. Gender differences in psychopathology, functional impairment, and familial risk factors among adjudicated delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:860–867. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Domalanta DD, Risser WL, Roberts RE, Risser JMH. Prevalence of depression and other psychiatric disorders among incarcerated youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:477–484. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046819.95464.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dembo R, Wothke W, Seeberger W, et al. Testing a model of the influence of family problem factors on high-risk youths’ troubled behavior: a three-wave longitudinal study. J Psychoact Drugs. 2000;32:55–65. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jargowsky PA. Take the money and run: economic segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas. Am Soc Rev. 1996;61:984–998. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenberg ML, O’Carroll PW, Powell KE. Let’s be clear: violence is a public health problem. JAMA. 1992;267:3071–3072. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.22.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.US Department of Health and Human Services. Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000 [PubMed]

- 73.Loeber R, Burke JD, Mutchka J, Lahey BB. Gun carrying and conduct disorder: a highly combustible combination? Implications for juvenile justice and mental and public health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:138–145. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;43:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003

- 76.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Characteristics of Homicides Reported by the New York City Police Department, NY Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at: http://bjsdata.ojp.usdoj.gov/dataonline/Search/Homicide/Local/RunHomJurisbyJuris.cfm Accessed November 11, 2003

- 77.Mulvey EP, Cauffman E. The inherent limits of predicting school violence. Am Psychol. 2001;56:797–802. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.10.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Menifield CE, Rose WH, Homa J, Cunningham AB. The media’s portrayal of urban and rural school violence: a preliminary analysis. Deviant Behav. 2001;22:447–464. [Google Scholar]