Abstract

Bacterial intercellular communication provides a mechanism for signal-dependent regulation of gene expression to promote coordinated population behavior. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium produces a non-homoserine lactone autoinducer in exponential phase as detected by a Vibrio harveyi reporter assay for autoinducer 2 (AI-2) (M. G. Surette and B. L. Bassler, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7046-7050, 1998). The luxS gene product mediates the production of AI-2 (M. G. Surette, M. B. Miller, and B. L. Bassler, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1639-1644, 1999). Environmental cues such as rapid growth, the presence of preferred carbon sources, low pH, and/or high osmolarity were found to influence the production of AI-2 (M. G. Surette and B. L. Bassler, Mol. Microbiol. 31:585-595, 1999). In addition to LuxS, the pfs gene product (Pfs) is required for AI-2 production, as well as S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) (S. Schauder, K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler, Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476, 2001). In bacterial cells, Pfs exhibits both 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA) and SAH nucleosidase functions. Pfs is involved in methionine metabolism, regulating intracellular MTA and SAH levels (elevated levels of MTA and SAH are potent inhibitors of polyamine synthetases and S-adenosylmethionine dependent methyltransferase reactions, respectively). To further investigate regulation of AI-2 production in Salmonella, we constructed pfs and luxS promoter fusions to a luxCDABE reporter in a low-copy-number vector, allowing an examination of transcription of the genes in the pathway for signal synthesis. Here we report that luxS expression is constitutive but that the transcription of pfs is tightly correlated to AI-2 production in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028. Neither luxS nor pfs expression appears to be regulated by AI-2. These results suggest that AI-2 production is regulated at the level of LuxS substrate availability and not at the level of luxS expression. Our results indicate that AI-2-dependent signaling is a reflection of metabolic state of the cell and not cell density.

Bacterial intercellular communication provides a mechanism for the regulation of gene expression, resulting in coordinated population behavior. This phenomenon has been referred to as quorum sensing or cell-cell communication and has been reviewed recently (1, 12, 17, 30, 34). Gram-negative bacteria typically produce, release, and respond to acyl-homoserine lactone (HSL) molecules (autoinducers) that accumulate in the external environment as the cell population grows. HSLs are synthesized by the LuxI family of HSL synthases and, above threshold concentrations, bind to their cognate receptor proteins (the LuxR family of transcriptional regulators) to mediate changes in gene transcription.

Unlike other gram-negative quorum-sensing organisms, Vibrio harveyi mediates quorum sensing via two parallel signaling systems, and detection and response to either signal is mediated by a two-component phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cascade (3, 15). The first signaling system is comprised of autoinducer 1 (AI-1), a hydroxybutanoyl-l-HSL (synthesized by LuxLM), and its cognate sensor protein LuxN, whereas the second signaling system is composed of AI-2 (synthesized by LuxS) and the LuxPQ sensor complex (6, 35, 39). Both signaling systems regulate a phosphorelay signaling pathway through LuxU to the transcriptional regulator LuxO to relieve repression of the lux operon (15). High concentrations of either AI-1 or AI-2 regulate bioluminescence (3), siderophore production, colony morphology, and possibly the expression of other LuxO-σ54-dependent genes in response to high cell density in V. harveyi (23).

V. harveyi reporter strains constructed to detect only AI-1 or AI-2 demonstrated that many species of bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Yersinia enterocolitica (2) produce autoinducers which induce bioluminescence through the AI-2 system of V. harveyi. The gene whose product is responsible for AI-2 production was initially identified in V. harveyi, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Escherichia coli and was named luxS (44). The luxS family of genes are highly homologous to one another but not to any other identified gene and define a new family of autoinducer-producing genes. In the National Center for Biotechnology Information microbial genome database, 30 of 136 bacterial species contain a luxS homologue. The luxS family of genes has widespread distribution among gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including pathogenic and nonpathogenic species (41).

More recently, luxS-dependent AI-2 signaling activity has been reported in many other bacteria including: E. coli O157 (37), Shigella flexneri (9), Helicobacter pylori (14, 22), Vibrio vulnificus (27), Streptococcus pyogenes (25), Mannheimia haemolytica (26), and Proteus mirabilis (36), as well as in periodontal pathogens such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (13), Prevotella intermedia, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Porphyromonas gingivalis (4, 7, 16). Recent studies with DNA arrays have implicated AI-2 in the regulation of a large number of genes in E. coli (10, 38). In Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, AI-2 regulates the expression of an outer membrane AI-2 transport protein (42).

A second protein (Pfs) is also required for AI-2 biosynthesis (35). Pfs catalyzes two reactions in bacterial cells: the formation of S-ribosylhomocysteine (SRH) from S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) to release adenine and the production of 5′-methylthioribose (MTR) from 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA), also releasing adenine (11, 19, 28). Both SAH and MTA are potent inhibitors of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-requiring reactions, and the accumulation of these metabolites is avoided through the activities of Pfs (8). The absence of pfs in E. coli results in severe growth defects (5). A recent study by Schauder et al. has shown that purified Pfs and LuxS enzymes are necessary and sufficient for AI-2 production in vitro with SAH as a substrate (35).

The environmental regulation of signal (AI-2) production in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 has been previously reported (40). Maximal AI-2 activity is produced during mid-exponential phase when Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is grown in the presence of glucose or other preferred carbohydrates (40). Degradation of the signal is believed to occur toward the onset of stationary phase or when the carbohydrate is depleted from the medium (40). Maximal signaling activity is also observed if, after growth in the presence of glucose, Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is transferred to high-osmolarity (0.4 M NaCl) or low-pH (pH 5.0) conditions (40). High osmolarity and low pH are environmental conditions that Salmonella serovar Typhimurium may encounter during infection, suggesting that quorum sensing may have a role in the regulation of virulence in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (40).

The purpose of this study is to determine how AI-2 production by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 is regulated at the genetic level by genes (luxS and pfs) whose products are directly involved in AI-2 generation. The analysis presented here demonstrates that the profile of pfs transcription is tightly correlated to the AI-2 production pattern in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 and that the transcription of luxS and pfs is not regulated by AI-2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All Salmonella strains were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm in Luria broth (LB; Gibco-BRL) containing 10 g of SELECT peptone 140, 5 g of SELECT yeast extract (low sodium), and 10 g of sodium chloride/liter with or without supplemented carbohydrate at 0.5% (wt/vol). V. harveyi was grown at 30°C with shaking at ca. 200 rpm in autoinducer bioassay (AB) medium as described previously (18). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: tetracycline, 15 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; and kanamycin, 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 | Wild type | ATCC 14028 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium CS132 | Isogenic to 14028 containing luxS::MudJ | 41 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SS007 | Isogenic to 14028 containing luxS::T-POP | 35 |

| V. harveyi BB170 | Isogenic to wild-type BB120 containing luxN::Tn5Kn | 3 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCS26 | Low-copy-number luxCDABE reporter vector | C. Southward |

| pAB12 | pCS26 containing luxS promoter | This study |

| pAB13 | pCS26 containing pfs promoter | This study |

| pBAD18 | Arabinose-inducible expression vector | Invitrogen; 21 |

| pMS234 | pBAD18 containing luxS | 35 |

DNA cloning.

All cloning vectors and plasmid constructs used in this study are listed in Table 1. The luxS and pfs promoter regions were cloned into a low-copy-number vector (pCS26), creating promoter-luxCDABE reporter transcriptional fusions to allow sensitive high-throughput analysis of promoter activity during growth. pCS26 is derived from pZS21-luc (24), which contains a low-copy-number pSC101 origin of replication, and a kanamycin resistance cassette. Additional modifications of pZS21-luc included replacement of the luciferase gene (luc) and the PLtetO-1 regulatory unit by the luxCDABE operon and a BamHI cloning site, respectively.

pAB12 was created by cloning the luxS promoter region from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 into the BamHI site of pCS26. The primers used to amplify the luxS promoter by PCR were luxS01 (CGGGG ATCCT TACCG TAATC TGTTA CGCG) and luxS02 (CGGGA TCCAA TAATG GCATT TAGTC ACCTC), generating a 405-bp fragment. pAB13 was created by cloning the pfs promoter region from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 into the BamHI site of pCS26. The primers used to amplify the pfs promoter by PCR were pfs01 (CGGGA TCCTC CATTG CGCCA ATGAT GCC) and pfs02 (CGGGA TCCTG AACGA TAACG ACGAT GCC), generating a 167-bp fragment. The resulting pAB12 and pAB13 constructs contain considerable regions upstream of luxS and pfs, respectively. Although the transcription start sites are not known (or predicted) for these genes, the cloned regions are sufficient to contain RNA polymerase binding and regulatory protein-binding sites. Similar luxS expression profiles were observed between the chromosomal luxS::MudJ lacZ transcriptional fusion and the cloned luxS-luxCDABE construct (pAB12), indicating that the complete promoter region was cloned. A larger clone of the pfs promoter region that included an additional 161 bp upstream gave similar results.

pMS234 was created by cloning the entire luxS gene from E. coli O157:H7 into the EcoRI and HindIII cloning sites of pBAD18 (Invitrogen) (21). The primers used to amplify the luxS gene by PCR were ygag01 (GTGAA GCTTG TTTAC TGACT AGATG TGC) and ygag03 (GTGTC TAGAA AAACA CGCCT GACAG).

PCR was perfomed in a Mastercycler gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf) with Taq polymerase (Gibco-BRL) and 55°C annealing temperature. Plasmid DNA was isolated by using QIA Spin Mini-Columns (Qiagen), and chromosomal DNA was isolated by the standard method of CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) extraction (44).

Correct plasmid constructs were confirmed by PCR-based sequencing by using a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (ABI PRISM) at the University Core DNA Sequencing Services (University of Calgary).

AI-2 bioassays.

The detection of AI-2 in culture supernatants by using V. harveyi BB170 was performed as previously reported (39). Briefly, the V. harveyi reporter strain was grown for ca. 16 h at 30°C at 200 rpm in AB medium (20). Cells were diluted 1/5,000 in fresh AB medium, and filter-sterilized culture supernatant samples were assayed at 10% (vol/vol) with the V. harveyi reporter strain BB170 (ΔluxN) to a final volume of 100 μl; the plates were then incubated with shaking at 30°C. Luminescence values were measured every hour in a Microbeta Liquid Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (Wallac model 1450) and reported as the fold induction of luminescence by the reporter strain above the negative medium control.

Gene expression analysis.

The promoter-luxCDABE fusions were used to measure promoter activity as counts per second (cps) of light in a Victor2 Multilabel Counter (Wallac model 1420). Overnight cultures were diluted 1/100 in LB with the appropriate antibiotic(s), and measurements were taken every hour during the growth curve. The growth of the cultures was determined by measuring the optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 100-μl samples in 96-well plates (path length of 0.4 cm) with the Victor2 Multilabel Counter. Gene expression was normalized per cell by dividing the luminescence value by the OD620 value of each sample.

luxS promoter activity was additionally examined with luxS-lacZ transcriptional fusions. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described by Miller (29) and expressed as β-galactosidase activity per OD600 unit (in Miller units). For autoregulation experiments, cells were grown in LB with or without 0.5% l-arabinose, harvested after 4 h growth at 37°C, and assayed for β-galactosidase activity (OD measurements were taken at 420, 550, and 600 nm in a Beckman DU640 spectrophotometer). All experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate.

RESULTS

Transcriptional analysis of luxS.

A transciptional fusion of the luxS promoter to the luxCDABE operon (pAB12) on a low-copy-number plasmid allowed sensitive, real-time, noninvasive monitoring of gene expression under a variety of growth conditions. By using this construct, we analyzed the transcription of luxS in conditions previously reported to result in minimal and maximal signaling activity by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, namely, in LB or in LB supplemented with 0.5% glucose (40).

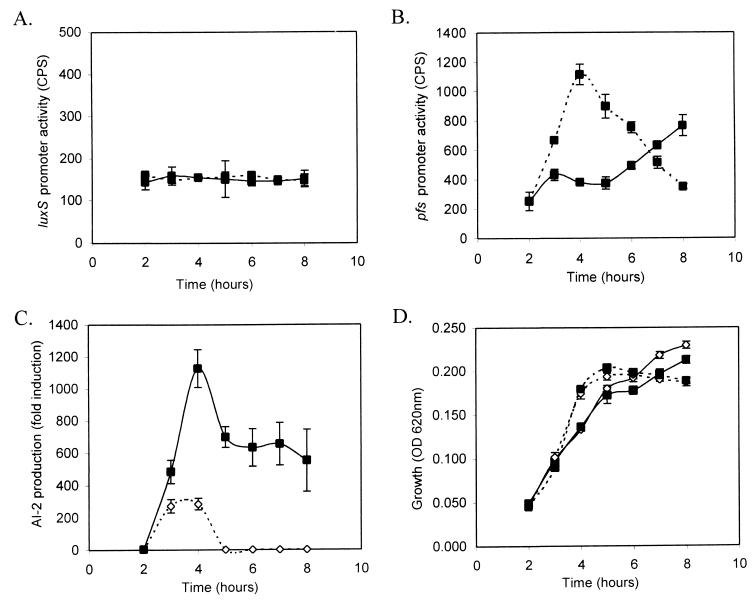

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028/pAB12 (luxS promoter-luxCDABE) was grown in LB with or without 0.5% glucose, and samples were removed every hour for OD and light output (cps) measurements, as well as for measurements of AI-2 activity. luxS was constitutively transcribed at low levels throughout the measured time points, and the addition of glucose to the culture medium resulted in minimal changes in gene expression (Fig. 1A). Similar results were obtained with a chromosomal luxS::MudJ lacZ transcriptional fusion (data not shown). The close agreement between the plasmid reporter and the chromosomal lacZ fusion validate the use of the plasmid-based reporter system in these studies. It should be emphasized that the use of low-copy-number vectors was important for this type of investigation.

FIG. 1.

Constitutive luxS expression and the correlation of pfs transcription to AI-2 production in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium during growth in LB medium with or without 0.5% glucose. luxS expression (A) and pfs expression (B) in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium during growth in LB medium with or without 0.5% glucose was measured by using low-copy-number luxCDABE reporter fusion to the luxS and pfs promoters. Solid line, LB; dashed line, LB with 0.5% glucose. (C) AI-2 production profile of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium during growth in LB media with or without 0.5% glucose. Supernatants were prepared from samples of growing cultures, filter sterilized, and assayed for AI-2 activity by using the V. harveyi BB170 AI-2 reporter strain. Samples collected from cultures grown in LB are shown by the broken line, and the dashed line represents AI-2 activity from cultures grown in LB with 0.5% glucose. (D) Growth curves of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 containing promoter-luxCDABE reporter vectors in LB or LB with 0.5% glucose are shown by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Symbols: ▪, 14028/pAB12; ⋄, 14028/pAB13.

Experiments were performed in an attempt to isolate mutations that resulted in changes in luxS transcription by random Tn10 mutagenesis. No luxS regulatory mutants were recovered in these screens of >35,000 colonies, a finding which supports our observations that luxS is not regulated at the transcriptional level.

We also examined changes in luxS transcription with quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis. RNA from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium was isolated each hour during growth in LB with or without glucose and then subjected to quantitative reverse transcription-PCR with a commercially available β-actin RNA as a control standard. The amount of luxS RNA transcripts observed was independent of the availability of glucose in the growth medium (data not shown).

The decrease in AI-2 production by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium that occurs in late log phase may also be due to changes in the level of LuxS enzymes, LuxS stability, or LuxS enzymatic activity. Through Western blot analysis, we examined LuxS stability in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium during growth. Preliminary results show that LuxS protein levels in stationary-phase cells are not lower than cells in exponential phase (data not shown), indicating that regulation of AI-2 production is not due to changes in LuxS levels during growth.

Transcriptional analysis of pfs.

Pfs catalyzes the production of SRH and MTR from SAH and MTA, respectively (11, 19, 28). The Pfs reaction product SRH is the substrate for LuxS. LuxS hydrolyzes SRH to homocysteine and AI-2 (35). A transcriptional fusion of the pfs promoter to the luxCDABE operon (pAB13) was used to analyze transcription of pfs in a manner similar to that described for the transcriptional analysis of luxS. Growth conditions were used that result in both minimal and maximal signal production by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium.

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028/pAB13 (pfs promoter-luxCDABE) was grown in LB with or without 0.5% glucose, and samples were removed every hour for OD and cps measurements, as well as for measuring the AI-2 activity. In contrast to luxS transcription, pfs expression was sensitive to the presence of glucose. pfs expression in LB with 0.5% glucose increased dramatically to a maximal value during the exponential phase and decreased upon entry into stationary-phase growth (Fig. 1B). The pfs transcriptional profile correlates with the observed pattern of AI-2 production in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, and maximal AI-2 production and pfs expression occurs at the same time. The AI-2 production profile by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 in LB with or without 0.5% glucose is shown in Fig. 1C. The increased presence of AI-2 activity at 3 and 4 h and the decrease beginning at 5 h correlates with the pfs expression pattern (Fig. 1B and C). Figure 1D shows that growth was unaffected by the presence of the reporter plasmids. These results indicate that the production of AI-2 by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is partially regulated at the transcriptional level of the pfs gene in the AI-2 synthesis pathway. Transcriptional fusions to the luxS and pfs promoters were also constructed by using lacZ as a reporter, and similar expression profiles were observed (data not shown).

Effects of different carbohydrates on pfs transcription and AI-2 production.

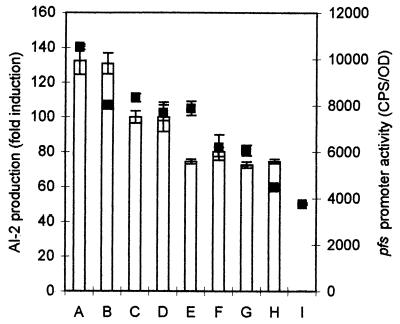

The AI-2 production profile by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium can be significantly different when carbohydrate supplements other than glucose are used in LB medium. Using pAB13 as a reporter construct for pfs transcription, we monitored pfs expression during growth in LB supplemented with 0.5% (nonlimiting) concentrations of various carbohydrates (Fig. 2). The following carbohydrates were tested: monosaccharides, including arabinose, galactose, and mannose; disaccharides, including maltose and melibiose; a trisaccharide (raffinose); and glycerol. Although the levels of AI-2 activity were dramatically affected by growth in alternative carbohydrate sources, these results show that, regardless of the carbohydrate supplement, pfs expression correlated to AI-2 production. For cultures supplemented with each of the carbohydrates, pfs expression and AI-2 production profiles were qualitatively similar to those of cultures supplemented with glucose; in each case, the maximum AI-2 production correlated with the peak in pfs expression (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of different carbohydrate supplements on pfs expression and AI-2 production. pfs expression (using pAB13) during growth in LB medium with 0.5% of various carbohydrates was measured every hour. The AI-2 activity of these cultures was also assayed by using V. harveyi BB170 AI-2 reporter strain on cell-free culture supernatants. The growth conditions (in columns A to I) were LB medium plus a 0.5% concentration of one of the following carbohydrates: A, arabinose; B, galactose; C, glucose; D, mannose; E, raffinose; F, melibiose; G, maltose; H, glycerol; and I, LB. The maximal AI-2 activity (bars) is depicted as a percentage relative to glucose, and pfs expression levels (datum points, ▪) are presented. In each case, they coincided at the same time point.

AI-2 does not regulate pfs and luxS transcription.

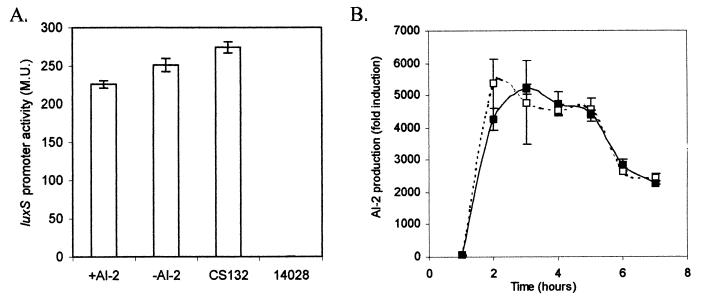

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium CS132 was used to analyze AI-2 regulation of luxS expression. CS132 has a luxS::lacZ transcriptional fusion created by a MudJ insertion in luxS. luxS expression was examined in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium CS132 with or without luxS complementation in trans by pMS234 (luxS cloned in the arabinose-inducible vector, pBAD18). Strains were grown in LB with or without 0.5% arabinose, and β-galactosidase assays performed at 4 h postsubculture when the cultures were growing maximally at mid-log phase. The results of these experiments indicated that overexpression of luxS in trans does not affect transcription of the native luxS promoter (Fig. 3A). In addition, we observed that LuxS overexpression from pMS234 in CS132 complements the AI-2 defect but does not result in increased AI-2 production from that generated by wild-type 14028, even though LuxS levels are much higher (Fig. 3B). This provides additional support for the hypothesis that AI-2 production by LuxS is regulated at the level of substrate (SRH) availability.

FIG. 3.

AI-2 does not regulate transcription of luxS. (A) The luxS::lacZ transcriptional fusion in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium CS132 (luxS::MudJ) was used to monitor luxS expression (β-galactosidase activity measured in Miller units [M.U.]). Mid-log-phase (4 h) luxS expression in CS132/pMS234 (pBAD18 containing luxS) was measured when AI-2 was produced during growth in LB plus 0.5% arabinose. The expression of luxS in CS132/pMS234 was determined in the absence of AI-2 during growth in LB without arabinose induction. luxS expression in CS132 without pMS234 and 14028 (negative control) are also shown. (B) Overexpression of LuxS does not result in increased AI-2 production over wild-type levels. AI-2 production levels by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 (wild type) and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium CS132 (luxS)/pMS234 are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively.

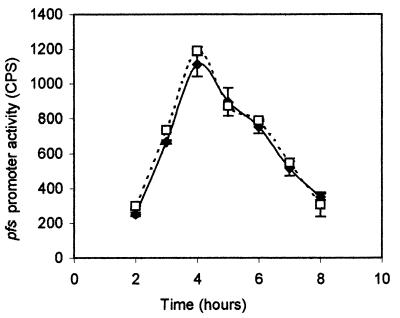

Possible regulatory effects on pfs transcription by AI-2 were also investigated. The pfs promoter fusion to luxCDABE (pAB13) was used to examine pfs transcription in the luxS mutant strain SS007 (luxS::T-POP) background and compared to that observed in wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 (Fig. 4). These expression studies indicated that pfs transcription is not affected by the availability of AI-2.

FIG. 4.

AI-2 does not regulate the transcription of pfs. The pfs-luxCDABE transcriptional fusion was used to monitor pfs expression in the presence or absence of AI-2 in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028 (luxS+) or SS007 (ΔluxS) strain backgrounds. pfs expression (light production) was measured in the two strains during growth in LB with 0.5% glucose. The pfs expression profile in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028/pAB13 is indicated by the solid line and in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SS007 (luxS::T-POP)/pAB13 by the dashed line.

In addition, no effect on luxS or pfs expression was observed when AI-2 was added exogenously. This finding provides additional support to our hypothesis that AI-2 does not affect expression of genes whose products are directly involved in its own production and regulation of luxS and pfs expression is at the level of substrate availability.

DISCUSSION

AI-2 is a unique bacterial signal since it is produced by both gram-negative and gram-positive species, and it has a novel structure. AI-2 is thought to be a universal signal and to mediate interspecies communication (34). The production of AI-2 by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is tightly regulated. Maximal signaling activity is observed during rapid growth in exponential phase with the presence of a preferred carbon source, including glucose (40). AI-2 production by a variety of bacteria has also been shown to be regulated by growth phase and media conditions (9, 14; A. L. Beeston and M. G. Surette, unpublished observations).

LuxS utilizes SRH to generate homocysteine and the AI-2 signal (35). The enzyme Pfs acts directly upstream of LuxS in the AI-2 production pathway and is responsible for generation of adenine and the LuxS substrate SRH from SAH (35). Although the contribution of the luxS transcriptional profile on the regulation of AI-2 production appears to be minimal, the pattern of pfs transcription is correlated to the AI-2 production profile in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 1 and 2) in LB medium containing glucose or alternative carbohydrate supplements. This result indicates that the tight regulation of AI-2 production by Salmonella is largely at the level of pfs transcription. The increase in AI-2 production due to osmotic or acid shock is not regulated at the level of pfs or luxS transcription, which suggests that these conditions may increase SAM utilization or alter Pfs and/or LuxS enzyme activity.

Although the maximal levels of pfs promoter activity and AI-2 production coincide temporally, the decrease in AI-2 levels after log-phase growth and pfs expression in LB without glucose supplements do not correlate as well. AI-2 degradation (40) or removal (42) at the onset of stationary phase is most likely responsible for this discrepancy. Alternatively, differences between AI-2 production and pfs transcription at this time or condition could be related to differences in the stability of Pfs or to various degrees of protein turnover in cells grown without glucose. The lux reporter is most likely not linked to this discrepancy since pfs expression profiles generated by luxCDABE and lacZ reporters were similar. The level of AI-2 is a consequence of both production and degradation rates, both of which may be independently subject to change during growth.

The decrease in pfs expression after maximum detectable levels of AI-2 production is consistent with a negative autoregulatory pattern. However, our results suggest that pfs is not transcriptionally regulated by the availability of AI-2 in the wild type or by the accumulation of the Pfs reaction product in the luxS null mutant (Fig. 4). In a luxS mutant, SRH is predicted to accumulate intracellularly since no enzymes other than LuxS are known to utilize SRH. The apparent accumulation of SRH does not result in toxicity, since we have observed that a luxS mutant shows no growth defects compared to wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium or E. coli. If the decrease in pfs expression is due to accumulation of SRH, the observation that pfs expression profiles are the same in wild-type and isogenic luxS mutant strains would indicate that AI-2 production is not the major pathway for SRH catabolism (or removal from the cell). It is possible that mechanisms other than LuxS activity function to catabolize SRH in bacteria. AI-2 production may also be dependent on the availability of SAH due to the utilization of SAH as a substrate by Pfs. Intercellular SAH levels will be dependent on methionine and SAM synthesis, in addition to SAM-dependent methyl transfer reactions, in one-carbon-compound metabolism, including DNA (restriction-modification, phase variation, DNA replication), RNA, and protein methylation (such as in chemotaxis).

Similarly, luxS transcription also is not regulated by a negative autoregulatory feedback loop (Fig. 3A). The decrease in AI-2 production observed during the late log phase and the stationary phase is not due to a decrease in luxS expression. Regulation of AI-2 production was shown to occur largely through the activity of the pfs promoter and is seemingly under the control of a regulatory network that is tightly linked to methionine metabolism. AI-2-dependent signaling may be a reflection of metabolic state of the cell or metabolic potential of the environment rather than a consequence of cell density as reported for HSL-dependent signaling. Futhermore, overexpression of LuxS does not result in increased AI-2 production (Fig. 3B), supporting our hypothesis that AI-2 production is limited by SRH availability.

In addition to the role of Pfs in AI-2 production, this enzyme may indirectly influence the activity of the LuxI family of HSL synthases. The dual functions of Pfs prevent the accumulation of MTA and SAH, both of which have been shown to inhibit the activity of the HSL synthase family of enzymes (31). AI-2 and HSL signal generation pathways are dependent on central methionine metabolism, since both are derived from SAM, an essential metabolite, and both involve Pfs activity.

The environment of the intestinal lumen has been reported to be rich in nutrients (including carbohydrates) and of low pH and high osmolarity (20). AI-2 production by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is also maximal under such conditions, suggesting that it may produce large amounts of AI-2 during infection (40). Interestingly, pfs is the first gene in a three-gene operon consisting of pfs, btuF, and yadS, where pfs and btuF have recently been shown to be cotranscribed (5). BtuF acts as a periplasmic vitamin B12 (cobalamin)-binding protein (5, 43), and the function of yadS has not been determined. Despite the genetic organization of these genes, the pfs and yadS gene products do not appear to be involved in cobalamin transport or utilization (5). Vitamin B12 synthesis is suppressed during aerobic growth and in media containing glucose (32), indicating that under these conditions Salmonella serovar Typhimurium requires BtuF-dependent cobalamin uptake from the environment. The coexpresssion of pfs and btuF (despite exhibiting different functions) indicates that pfs expression is high in conditions of excess vitamin B12. We have observed increased pfs expression in LB media containing 0.5% glucose with 0.5 to 5.0 μM cyanocobalamin or hydroxycobalamin supplements (data not shown).

The vitamin B12 biosynthetic pathway is not required for virulence of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (33), suggesting that significant amounts of vitamin B12 are present in the intestinal tract. The presence of pfs and btuF in the same operon may have evolved to facilitate coregulation in similar environments. Interestingly, pfs and btuF share an operon only in enteric species, suggesting that AI-2 production is tightly linked to cobalamin uptake in the intestinal tract. Understanding that the molecular basis of the regulation of AI-2 production by pathogenic bacteria is at the level of pfs expression may lead to the development of therapeutics that interfere with AI-2-dependent signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Bassler for V. harveyi BB170, helpful discussions, and advice; S. Schauder for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SS007 and anti-LuxS sera; C. Southward for constructing the luxCDABE reporter vector; and lab members for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). M.G.S. is also an AHFMR and CIHR scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler, B. L. 1999. How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:582-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler, B. L., E. P. Greenberg, and A. M. Stevens. 1997. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 179:4043-4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassler, B. L., M. Wright, and M. R. Silverman. 1994. Multiple signalling systems controlling expression of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes encoding a second sensory pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 13:273-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess, N. A., D. F. Kirke, P. Williams, K. Winzer, K. R. Hardie, N. L. Meyers, J. Aduse-Opoku, M. A. Curtis, and M. Camara. 2002. LuxS-dependent quorum sensing in Porphyromonas gingivalis modulates protease and haemagglutinin activities but is not essential for virulence. Microbiology 148:763-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadieux, N., C. Bradbeer, E. Reeger-Schneider, W. Koster, A. K. Mohanty, M. C. Wiener, and R. J. Kadner. 2002. Identification of the periplasmic cobalamin-binding protein BtuF of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:706-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao, J. G., and E. A. Meighen. 1989. Purification and structural identification of an autoinducer for the luminescence system of Vibrio harveyi. J. Biol. Chem. 264:21670-21676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, W. O., Y. Park, R. J. Lamont, R. McNab, B. Barbieri, and D. R. Demuth. 2001. Signaling system in Porphyromonas gingivalis based on a LuxS protein. J. Bacteriol. 183:3903-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornell, K. A., R. W. Winter, P. A. Tower, and M. K. Riscoe. 1996. Affinity purification of 5-methylthioribose kinase and 5-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biochem. J. 317:285-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day, W. A., Jr., and A. T. Maurelli. 2001. Shigella flexneri LuxS quorum-sensing system modulates virB expression but is not essential for virulence. Infect. Immun. 69:15-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLisa, M. P., C. F. Wu, L. Wang, J. J. Valdes, and W. E. Bentley. 2001. DNA microarray-based identification of genes controlled by autoinducer 2-stimulated quorum sensing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5239-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Della Ragione, F., M. Porcelli, M. Carteni-Farina, V. Zappia, and A. E. Pegg. 1985. Escherichia coli S-adenosylhomocysteine/5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase: purification, substrate specificity, and mechanism of action. Biochem. J. 232:335-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunny, G. M., and B. A. Leonard. 1997. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:527-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong, K. P., W. O. Chung, R. J. Lamont, and D. R. Demuth. 2001. Intra- and interspecies regulation of gene expression by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans LuxS. Infect. Immun. 69:7625-7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsyth, M. H., and T. L. Cover. 2000. Intercellular communication in Helicobacter pylori: luxS is essential for the production of an extracellular signaling molecule. Infect. Immun. 68:3193-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman, J. A., and B. L. Bassler. 1999. Sequence and function of LuxU: a two-component phosphorelay protein that regulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 181:899-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frias, J., E. Olle, and M. Alsina. 2001. Periodontal pathogens produce quorum sensing signal molecules. Infect. Immun. 69:3431-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray, K. M. 1997. Intercellular communication and group behavior in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 5:184-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg, E. P., J. W. Hastings, and S. Ulitzur. 1979. Induction of luciferase synthesis in Beneckea harveyi by other marine bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 120:87-91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene, R. C. 1996. Biosynthesis of methionine, p. 542-560. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Guiney, D. G. 1997. Regulation of bacterial virulence gene expression by the host environment. J. Clin. Investig. 99:565-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joyce, E. A., B. L. Bassler, and A. Wright. 2000. Evidence for a signaling system in Helicobacter pylori: detection of a luxS-encoded autoinducer. J. Bacteriol. 182:3638-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilley, B. N., and B. L. Bassler. 2000. Regulation of quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi by LuxO and sigma-54. Mol. Microbiol. 36:940-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutz, R., and H. Bujard. 1997. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1203-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyon, W. R., J. C. Madden, J. C. Levin, J. L. Stein, and M. G. Caparon. 2001. Mutation of luxS affects growth and virulence factor expression in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 42:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malott, R. J., and R. Y. Lo. 2002. Studies on the production of quorum-sensing signal molecules in Mannheimia haemolytica A1 and other Pasteurellaceae species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDougald, D., S. A. Rice, and S. Kjelleberg. 2001. SmcR-dependent regulation of adaptive phenotypes in Vibrio vulnificus. J. Bacteriol. 183:758-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, C. H., and J. A. Duerre. 1968. S-Ribosylhomocysteine cleavage enzyme from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 243:92-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Miller, M. B., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsek, M. R., D. L. Val, B. L. Hanzelka, J. E. Cronan, Jr., and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Acyl homoserine-lactone quorum-sensing signal generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4360-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roth, J. R., J. G. Lawrence, and T. A. Bobik. 1996. Cobalamin (coenzyme B12): synthesis and biological significance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:137-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampson, B. A., and E. C. Gotschlich. 1992. Elimination of the vitamin B12 uptake or synthesis pathway does not diminish the virulence of Escherichia coli K1 or Salmonella typhimurium in three model systems. Infect. Immun. 60:3518-3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schauder, S., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The languages of bacteria. Genes Dev. 15:1468-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schauder, S., K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider, R., C. V. Lockatell, D. Johnson, and R. Belas. 2002. Detection and mutation of a luxS-encoded autoinducer in Proteus mirabilis. Microbiology 148:773-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperandio, V., J. L. Mellies, W. Nguyen, S. Shin, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. Quorum sensing controls expression of the type III secretion gene transcription and protein secretion in enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:15196-15201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, J. A. Giron, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 183:5187-5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surette, M. G., and B. L. Bassler. 1998. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7046-7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surette, M. G., and B. L. Bassler. 1999. Regulation of autoinducer production in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 31:585-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Surette, M. G., M. B. Miller, and B. L. Bassler. 1999. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Vibrio harveyi: a new family of genes responsible for autoinducer production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1639-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taga, M. E., J. L. Semmelhack, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS-dependent autoinducer AI-2 controls the expression of an ABC transporter that functions in AI-2 uptake in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 42:777-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Bibber, M., C. Bradbeer, N. Clark, and J. R. Roth. 1999. A new class of cobalamin transport mutants (btuF) provides genetic evidence for a periplasmic binding protein in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 181:5539-5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, K. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.