Abstract

The bgl promoter is silent in wild-type Escherichia coli under standard laboratory conditions, and as a result, cells exhibit a β-glucoside-negative (Bgl−) phenotype. Silencing is brought about by negative elements that flank the promoter and include DNA structural elements and sequences that interact with the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. Mutations that confer a Bgl+ phenotype arise spontaneously at a detectable frequency. Transposition of DNA insertion elements within the regulatory locus, bglR, constitutes the major class of activating mutations identified in laboratory cultures. The rpoS-encoded σS, the stationary-phase sigma factor, is involved in both physiological as well as genetic changes that occur in the cell under stationary-state conditions. In an attempt to see if the rpoS status of the cell influences the nature of the mutations that activate the bgl promoter, we analyzed spontaneously arising Bgl+ mutants in rpoS+ and rpoS genetic backgrounds. We show that the spectrum of activating mutations in rpoS cells is different from that in rpoS+ cells. Unlike rpoS+ cells, where insertions in bglR are the predominant activating mutations, mutations in hns make up the majority in rpoS cells. The physiological significance of these differences is discussed in the context of survival of natural populations of E. coli.

The bgl operon (Fig. 1) is one of four β-glucoside utilization systems pre sent in Escherichia coli. It specifies the genes required for the uptake and utilization of the aromatic β-glucosides, salicin and arbutin (22). Wild-type cells are Bgl−, i.e., they cannot utilize arbutin and salicin, at least under laboratory conditions, because the expression of the bgl genes is significantly reduced by silencing elements that include DNA structural elements as well as the global repressor, H-NS (19, 21, 25, 31). However, Bgl+ mutants arise spontaneously at a detectable frequency. Most activating mutations isolated in the laboratory are insertion elements (ISs) within the regulatory region, bglR (23, 24, 27), that distance or disrupt the negative elements (19, 21, 25). Point mutations in the CRP-binding site (19, 24) and unlinked mutations at loci, such as hns (12), gyrA, gyrB (5), bglJ (6), and leuO (33), also activate the operon. Once activated, the operon is inducible by salicin and arbutin, and its transcription is regulated by antitermination (20, 26) involving modulation of the binding of the antiterminator to mRNA (13) by phosphorylation (1). The mechanism underlying the silencing of the bgl operon in wild-type cells has been extensively studied (3, 21). From an evolutionary viewpoint, retention of the wild-type operon in a silent form, without the structural genes accumulating mutations, is intriguing.

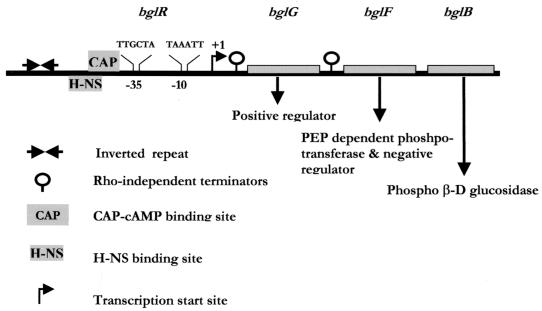

FIG. 1.

The bgl operon of E. coli. The region upstream of the structural genes is termed bglR. Activation of the operon occurs predominantly by insertions in bglR. Negative regulatory elements, such as the inverted repeat that can extrude into a cruciform and the H-NS binding region, ensure the silencing of the operon in wild-type cells. The catabolite gene activator protein-cyclic AMP (CAP-cAMP) binding site, present upstream of the promoter, overlaps with the H-NS binding site. BglG, which functions as an antiterminator at the two Rho-independent terminators, brings about salicin-inducible transcription of the bgl genes upon activation. PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Faced with environmental stress, microbial populations respond by activating inducible systems or, alternatively, exploit genetic processes that can help select for cells better adapted to the new environment. A genetic system that is activated by mutation or recombination may be of particular relevance for enteric bacteria like E. coli that are subjected to frequent changes in their immediate environment. The bgl operon, with its unusual regulatory mechanism, may represent one such system. The bgl genes may be retained in wild-type populations by oscillations between the silent and active states of the operon, with each state providing growth advantage in a different environment (10). Since a majority of the Bgl+ mutants isolated from wild-type (Bgl−) cultures in the laboratory carry insertions of IS1 and IS5 in bglR, it has been suggested that the transposition of mobile genetic elements could be instrumental in bringing about oscillations between the active and silent states by insertion and precise excision (10). But IS-mediated alternation between active and silent states does not seem possible, at least under laboratory conditions, since in most of the revertants of an IS1-activated strain, the operon is permanently inactivated as a consequence of IS1-mediated deletions of the structural genes (38).

The rpoS-encoded σS, the stationary-phase sigma factor, is a key player that enables the cell to survive stress and stasis (18). When cells enter the stationary state, the expression of almost 100 different genes, whose main function is to protect the cell against a variety of stresses (σS regulon) is induced or derepressed. This activation is brought about in an RpoS-dependent manner in concert with a combination of one or more global regulators such as Lrp, H-NS, and IHF (11, 14, 37). A number of chromosomal genes, including rpoS, affect the transpositions of mobile genetic elements. RpoS has been shown to be required for phage Mu-mediated DNA rearrangements (7, 17). Paradoxically, mutations in rpoS also confer a growth advantage in the stationary phase and are the first in a series of genetic changes detected in survivors of prolonged starvation, enabling the efficient scavenging of available nutrients in the environment (40).

Since rpoS has been implicated in both physiological as well as genetic changes that occur in the cell in stationary-state conditions, we have analyzed spontaneous Bgl+ mutants of wild-type and rpoS cells and show that the spectrum of activating mutations is different in an rpoS background. The physiological significance of this observation, in terms of colonization by E. coli of its natural habitat, the mammalian large intestine, and secondary habitats, such as soil, is examined.

The rpoS mutant strain forms papillae earlier and more frequently than the isogenic rpoS+ strain.

The wild-type strains RV (bglR0 rpoS+) and SM2 (bglR0 rpoS::Tn10) are isogenic (Table 1). Appropriate dilutions of RV and SM2 were plated on MacConkey-salicin plates and subjected to prolonged incubation to allow the colonies to form papillae. We observed that SM2 formed papillae earlier than RV (∼24 h for SM2 compared to ∼36 h for RV), and there were, on the average, more papillae per colony of SM2. The papillae frequency (measured as the number of papillae/the number of cells) of SM2 was two orders of magnitude higher than that of RV (14.5 × 10−7 for SM2 versus 16.2 × 10−9 for RV). The mean number of Sal+ colonies arising when overnight cultures of both were plated on minimal salicin plates was also similarly higher for SM2 compared to RV. This indicates that disruption of rpoS enhances the mutational activation of bgl.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| RV+ | F− ΔlacX74 thi bglR11 (bglR::IS1) (Bgl+) | A. Wright |

| RV | F− ΔlacX74 thi bglR0 (Bgl−) | A. Wright |

| SM2 | RV rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| MM1 | F− ΔlacX74 thi bglR0tna::Tn10 (Bgl−) | M. Mukerji |

| AE328 | ΔlacX74 thi bglR11 (bglR::IS1) tna::Tn10 (Bgl+) | A. Wright |

| RVp1-1.31 | Papillae from RV (Bgl+) | This work |

| SM2p1-1.32 | Papillae from SM2 (Bgl+) | This work |

| MM1pap1-15 | Papillae from MM1 (Bgl+) | This work |

| Hfr strains | 30 | |

| CAG12200 | KL16 zed-3120::Tn10Kan | |

| CAG12201 | KL14 thi-3178::Tn10Kan | |

| CAG12202 | KL96 trpB3193::Tn10Kan | |

| CAG12203 | KL208 zbc-3105::Tn10Kan | |

| CAG12205 | KL228 zgh-3159::Tn10Kan | |

| CAG12206 | HfrH nadA3052::Tn10Kan | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJL3 | bglJ4, BamHI-NheI fragment in pSK Apr | 6 |

| pHMG409 | hns, EcoRI-StuI fragment in pLG339 Kan | 8 |

Most rpoS papillae do not carry insertions in bglR.

About 30 papillae from each strain were purified and further analyzed by Southern hybridization or PCR of the bglR region to determine the nature of the activating mutation. Wild-type RV, IS1-activated RV+, and IS5-activated RVp3 (previously isolated and characterized) were used as controls, and IS1 or IS5 insertions in bglR were identified as having increased band sizes compared to the wild type (Fig. 2). A remarkable difference was apparent when the activating mutations in the rpoS+ and rpoS mutant backgrounds were compared (Table 2). In RV, most of the mutants (∼80%) showed insertional activation, more than half of which were activated by IS1. On the other hand, in SM2 only about 33% (9 of 30 analyzed) showed insertions in bglR (Fig. 2). Of these, two were activated by insertions of IS1 and five were activated by an insertion of IS5. In the remaining two (SM2p1.7 and SM2p1.15), the size of the insertion did not match either IS1 (∼0.7 kb) or IS5 (1.2 kb). On the basis of size and restriction analysis, this insertion was identified as IS10. In both of these mutants, the orientation of the IS10 element was opposite to that of the operon. Thus, unlike in the wild type, in the majority of SM2 papillae (∼67%), activation did not involve IS1 and IS5 elements and the bglR locus remained unaltered with respect to size.

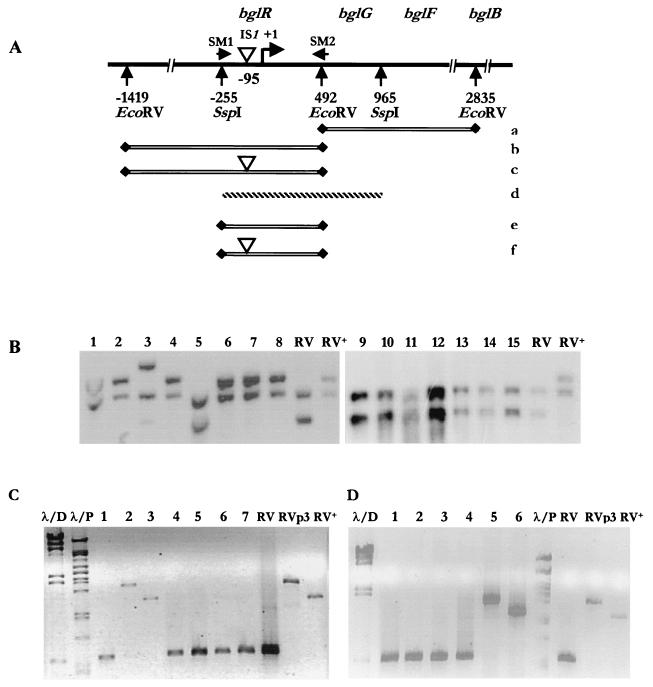

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematic representation of the molecular analysis of the bgl operon of wild-type cells and Bgl+ mutants. (a to d) Expected bands of genomic DNA digested with EcoRV. (d) The 1.2-kb fragment obtained by SspI digestion of the plasmid carrying the wild-type operon used as a probe. This detects two bands, a 2.3-kb downstream fragment (a) and an upstream fragment (b), which is 1.9 kb in the wild-type and noninsertionally activated operons. (c) This increases in size to 2.6, 3.1, or 3.2 kb upon activation of the operon by the insertion of IS1, IS5, or IS10, respectively. (e and f) Expected bands obtained in PCR analysis. Primers SM1 and SM2 amplify an ∼560-bp region in wild-type and noninsertionally activated operons (e). (f) Insertion of IS1, IS5, or IS10 results in a larger product, 1.3, 1.8, or 1.9 kb, respectively. (B) Representative Southern analysis of RV (lanes 1 to 8) and SM2 (lanes 9 to 15) papillae. Except for RVp3 (bglR::IS5) (lane 3) and RVp5 (wild type) (lane 5), all strains show an increase in size in the 1.9-kb band suggestive of IS1 insertion. All seven SM2 papillae show bands similar to that of the wild-type strain. The wild type, RV, and RV+ (bglR::IS1) are controls. PCR analysis of representative papillae of SM2 (C) and RV (D). SM2p1.18 is activated by IS5 (lane 2) and SM2p1.19 is activated by IS1 (lane 3), whereas SM2p1.17, 1.21, 1.22, 1.23, and 1.24 show products with sizes similar to that of the wild type (lanes 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively). RVp1.12 is activated by IS5 (lane 5) and RVp1.13 is activated by IS1 (lane 6), whereas RVp1.3, 1.6, 1.8, and 1.9 show products with sizes similar to that of the wild type (lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively). λ/D and λ/P are size markers. The wild type, RV, RV+ (bglR::IS1), and RVp3 (bglR::IS5) were used as controls in the PCR analysis.

TABLE 2.

Spectrum of bgl-activating mutations in RV and SM2 papillaea

| Strain (genotype) | No. of mutations linked to bgl

|

No. of mutations not linked to bgl

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS1 | IS5 | Other inser- tion | No inser- tion | hns | bglJ | leuO | Other | |

| RV (bglR0rpoS+) | 15 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SM2 (bglR0rpoS::Tn10) | 2 | 5 | 2b | 0 | 8 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

The strains were streaked to isolation on MacConkey-salicin indicator plates and incubated at 37°C until red Sal+ papillae appeared as a result of mutation. Papillae from different colonies were purified and analyzed to determine the nature of the bgl-activating mutations. A total of 30 papillae were analyzed in each strain background. The numbers of different types of activating mutations identified in the rpoS+ and rpoS backgrounds are represented.

Both of these papillae were activated by insertions of IS10 in bglR.

All activating mutations in rpoS+ papillae are linked to the bgl operon while all noninsertional mutations in the rpoS mutant papillae are unlinked.

All Bgl+ mutants of both RV and SM2 that did not carry insertions in bglR were subjected to further analysis. Firstly, they were transduced with a P1 lysate prepared from a strain carrying the wild-type bgl operon linked to recF::Tn3 to determine whether the activating mutations are located within the operon. It was seen that all 6 noninsertional mutations in RV were linked to bgl, whereas in SM2 all 21 of the mutations were unlinked. Since Southern analysis and PCR of the bglR region did not indicate sizes different from those of the wild type (Fig. 2), the RV mutations are probably point mutations or small deletions.

The loci likely to be mutated in the SM2 Sal+ papillae are the other β-glucoside-utilizing operons, namely the cel and asc operons, both of which are activated by insertions (9, 16), the global repressor hns (12), the gyrase genes, gyrA and gyrB (5), and the recently identified transactivators, bglJ (6) and leuO (33). To verify that the Sal+ phenotype in the SM2 mutants was a consequence of the activation of the bgl operon rather than of other β-glucoside-utilizing operons, bgl transcript levels in the wild-type and activated strains were measured. The level of bgl transcript in the mutants was comparable to that of an IS1-activated strain, AE328 (Fig. 3). Further, all mutants were found to be Cel− (unable to utilize cellobiose), confirming that the Bgl+ phenotype in these strains is independent of the involvement of the cel and asc operons. Spontaneous mutations that inactivate the gyrase genes, leading to bgl activation, are unlikely, as they are expected to be lethal and can be isolated only under specific conditions. When the growth of the mutants was monitored at 37 and 42°C, they showed the same growth rate at 42°C as the wild type, suggesting that they do not harbor conditional mutations in gyrA or gyrB.

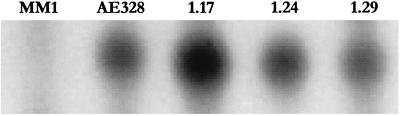

FIG. 3.

Detection of bgl transcript levels from representative SM2 papillae, SM2p1.17, SM2p1.24, and SM2p1.29 (Bgl+) with the S1 nuclease protection assay as described previously (35). Wild-type MM1 (bglR0) and activated AE328 (bglR::IS1) are the controls. No transcript can be detected in MM1, but the SM2 papillae show transcript levels comparable to those of the insertionally activated strain, indicating that the Sal+ phenotype of the mutants is due to enhanced bgl transcription.

Activating mutations in the rpoS papillae map to two loci: hns and bglJ.

The strains derived from SM2 papillae that did not carry an insertion in bglR were checked for complementation with the plasmid pHMG409 carrying the wild-type hns gene. Of the 21 strains tested, 8 mutants were complemented by hns. The activating mutations in the remaining 13 papillae were mapped to a region within 95 to 5 min of the E. coli chromosome with the Hfr mapping set (30). Both bglJ (99.2 min) and leuO (1.8 min) lie in this region. Mutations in these two loci were checked by P1 transduction with strains carrying Tn5 insertions linked to the two loci. Based on these analyses, the mutations were found to be linked to bglJ in all 13 of the strains. The original bglJ-activating mutation was an IS10R insertion upstream of the gene, resulting in overproduction of the BglJ protein, a putative activator of the bgl operon. The SM2-derived bglJ strains were subjected to Southern analysis to determine whether the activating mutation was an insertion in these strains, too. At least five representative strains were found to carry an insertion that, on the basis of size, is likely to be IS10 (Fig. 4). Although, leuO was also identified as a transactivator of bgl as a result of insertional activation by mini-Tn10 Cm leading to overexpression, none of the SM2 papillae appeared to be mutated in leuO. Thus, there are differences in the spectrum of the activating mutations in rpoS+ and rpoS strains.

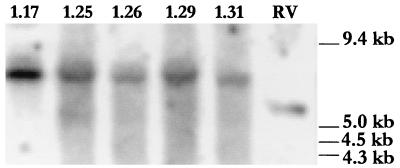

FIG. 4.

Southern analysis of the bglJ region of representative SM2 mutants showing an insertion of ∼1.4 kb. Genomic DNA of the mutants was digested with BamHI and probed with linearized pJL3. RV (Bgl−), which has wild-type bglJ, shows a band of ∼6 kb while SM2p1.17, 1.25, 1.26, 1.29, and 1.31 (Bgl+) show bands of ∼7.5 kb, indicating an insertion.

Most activating mutations in a Tn10-carrying rpoS+ strain also map to bglJ.

While RV and SM2 are isogenic at all loci except rpoS, there is a major difference between the two: in SM2, a Tn10 element disrupts rpoS. Thus, SM2 is an rpoS mutant but also carries a copy of IS10R capable of transposition. The differences in activation between the two strains may be a result of the activity of IS10R. To verify this, an rpoS+ tna::Tn10 Bgl− strain (MM1) was allowed to form papillae and the papillae were analyzed to determine the nature of the activating mutations. MM1 was found to form papillae at a frequency that is an order of magnitude lower than that of SM2 (∼10−8). The majority of the activating mutations were found to be linked to bglJ (14 out of 15 papillae). Unlike in SM2, mutations in hns were not identified. These results indicate that, though mutations in bglJ may be related to the presence of IS10 in the genome and may occur irrespective of the rpoS status, mutations in hns are seen only in the rpoS mutant genetic background.

The genomes of stationary-state cultures have been shown to be dynamic, and this allows accumulation of changes that improve the fitness of individual cells in the population (40). Since σS is the central regulator of cellular changes during starvation, the present study was aimed at analyzing activation of the bgl operon in rpoS+ and rpoS cells. Given that ISs constitute the predominant class of bgl-activating mutations, such a study would help towards understanding the role of insertional activation in environments outside the laboratory.

Unlike the rpoS+ strain RV, most of the mutations in the rpoS strain SM2 (rpoS::Tn10) are not linked to the bgl operon. They fall into two categories. Mutations in hns account for about half of them; the remaining mutations are linked to bglJ, a putative activator of bgl. The nature of the hns mutation is not known, but the bglJ mutation is an insertion, probably of IS10, similar to the original activating mutation (6). The activity of IS10R is tightly regulated; its transposition occurs preferentially after DNA replication (4, 29). It is therefore likely that SM2 appears to form papillae earlier due to IS10 transposition early during colony growth when cells are actively dividing; other activating mutations (such as IS1 and IS5 insertions) occur once cells in the colony stop dividing. This activity of IS10 is apparently the same in rpoS+ and rpoS cells. Irrespective of the IS10 status, the major difference between the two strains is the high frequency of the hns mutations seen exclusively in the rpoS background. The increase in papillae frequency in SM2 is due to two factors: the presence of IS10 in the genome and its transposition and increased mutations in hns associated with the rpoS genetic background.

H-NS is a global inhibitor of gene expression during the exponential phase. Mutations in hns pleiotropically increase the expression of various genes, which include rpoS itself (39) and a large number of genes belonging to the σS regulon (2). Repression of these stress response genes is mediated by H-NS either indirectly via its negative regulation of RpoS or directly by binding to the control regions of these genes. H-NS is believed to have a direct role in silencing the bgl promoter (21, 28), and the activating insertions disrupt this interaction. Since the predominant mutations that activate the operon in an rpoS+ background are insertions of ISs, the higher frequency of hns mutations in the rpoS background is suggestive of the fact that selection for these mutations is independent of their positive effect on bgl. This is further supported by the observation that four out of five Bgl+ mutants isolated under nonselective conditions from an aged culture of an RpoS-attenuated strain bearing the rpoS819 allele (40) carried mutations in hns (S. Mahadevan and R. Kolter, unpublished data).

Natural microbial populations spend the majority of their lives under starvation stress interspersed with sporadic and short-lived periods of growth when nutrients become available, a feast-and-famine lifestyle (15). While the overall population of stationary-phase E. coli cultures may be considered starved, such populations are highly dynamic, and subpopulations arise that consist of mutants with enhanced fitness during starvation. Most of these subpopulations bear a mutation in rpoS and consequently have attenuated expression of the σS regulon (40). Additional mutations in the rpoS background enhance the ability of the cells to scavenge for available nutrients and grow rapidly (41). Thus, rather than maintain a highly resistant nongrowing state, these mutants continue to grow and out compete the wild-type cells in the stationary phase (35). That such population takeovers by rpoS cells may be occurring in nature is supported by the allelic variation found in the rpoS gene in strains isolated from long-term laboratory cultures as well as from host organisms and secondary environments (32, 34, 36). The balance between the wild-type rpoS and its attenuated counterparts will probably depend on the typical amount of time between two feast periods. In nutritionally rich environments, the mortality rate of the wild type would be relatively high and population shifts may be very rapid. In low-nutrient stressful environments, such as minimal media, soil, and water, maintenance and stress resistance functions are of major importance for long-term survival. In such environments, the mortality of the wild type would be low; on the other hand, that of mutants with an attenuated RpoS would be higher since, in these, survival functions would be compromised.

The only other global regulator so far found to accumulate mutations in aged cultures is Lrp (42). Mutations in regulators such as these make global shifts in metabolism and physiology, often with coordinated effect. Alterations in the function of a global regulator would alter several activities and may result in a fitness gain higher than that resulting from altering a single activity. The results reported here suggest that the effect of hns mutations in an rpoS background may be similar. Given that hns normally represses exponential-phase expression of the σS regulon, cells with hns rpoS double mutations would not only be able to grow rapidly but would also be able to endure stress better. This is consistent with the report that hns rpoS double mutants have a faster doubling time than rpoS single mutants (2). Though the effect on bgl expression may be indirect, the differential spectrum of mutations that activate the bgl genes has provided the indication that there is positive selection for hns mutations in an rpoS background.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Wright, J. Lopilato, and J. Gowrishankar for bacterial strains and plasmids and K. Manjula Reddy for help with mapping of the mutations. We also thank the two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions for improving the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant SP/SO//D62/97 to S.M. from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amster-Choder, O., and A. Wright. 1992. Modulation of the dimerization of an antiterminator protein by phosphorylation. Science 257:1395-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth, M., C. Marschall, A. Muffler, D. Fischer, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1995. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of σS and many σS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:3455-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caramel, A., and K. Schnetz. 1998. Lac and lambda repressors relieve silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter: activation by alteration of a repressing nucleoprotein complex. J. Mol. Biol. 284:875-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Case, C. C., S. M. Roels, J. E. Gonzalez, E. L. Simons, and R. W. Simons. 1988. Analysis of the promoters and transcripts involved in IS10 anti-sense RNA control. Gene 72:219-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Nardo, S., K. A. Voelkel, R. Sternglanz, A. E. Reynolds, and A. Wright. 1982. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants have compensatory mutations in the DNA gyrase genes. Cell 31:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giel, M., M. Desnoyer, and J. Lopilato. 1996. A mutation in a new gene, bglJ, activates the bgl operon in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics 143:627-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Gomez, J. M., J. Blazquez, F. Baquero, and J. L. Martinez. 1997. H-NS and RpoS regulate emergence of Lac Ara+ mutants of Escherichia coli MCS2. J. Bacteriol. 179:4620-4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goranson, M., B. Sonden, P. Nilsson, B. Dagberg, K. Forsman, K. Emanuelsson, and B. E. Uhlin. 1990. Transcriptional silencing and thermoregulation of genes in Escherichia coli. Nature 344:682-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall, B. G., and L. Xu. 1992. Nucleotide sequence, function, activation and evolution of the cryptic asc operon of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9:688-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall, B. G., S. Yokoyama, and D. H. Calhoun. 1983. Role of cryptic genes in microbial evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1:109-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1996. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase, p. 1497-1512. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Higgins, C. F., C. J. Dorman, D. A. Stirling, L. Waddel, I. R. Broth, G. May, and E. Bremer. 1988. Physiological role of DNA supercoiling in the osmotic regulation of gene expression in S. typhimurium and E. coli. Cell 52:569-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houman, F., M. R. Diaz-Torres, and A. Wright. 1990. Transcriptional antitermination in the bgl operon of E. coli is modulated by a specific RNA binding protein. Cell 62:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihama, A. 1997. Adaptation of gene expression in stationary phase bacteria. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7:582-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch, A. L. 1971. The adaptive responses of Escherichia coli to a famine and feast existence. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 6:147-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kricker, M., and B. G. Hall. 1987. Biochemical genetics of the cryptic gene system for cellobiose utilization in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics 115:419-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamrani, S., C. Ranquet, M. Gama, H. Nakai, J. Shapiro, A. Toussaint, and G. Maenhaut-Michel. 1999. Starvation-induced Mucts62-mediated coding sequence fusion: a role for ClpXP, Lon, RpoS and Crp. Mol. Microbiol. 32:327-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange, R., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1991. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopilato, J., and A. Wright. 1990. Mechanism of activation of the cryptic bgl operon of E. coli K-12, p. 435-444. In K. Drlica and M. Riley (ed.), The bacterial chromosome. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Mahadevan, S., and A. Wright. 1987. A bacterial gene involved in transcription antitermination: regulation at a rho-independent terminator in the bgl operon of E. coli. Cell 50:485-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukerji, M., and S. Mahadevan. 1997. Characterization of the negative elements involved in silencing the bgl operon of Escherichia coli: possible roles for DNA gyrase, H-NS, and CRP-cAMP in regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 24:617-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad, I., and S. Schaefler. 1974. Regulation of the β-glucoside system in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 120:638-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds, A. E., J. Felton, and A. Wright. 1981. Insertion of DNA activates the cryptic bgl operon of E. coli. Nature 293:625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds, A. E., S. Mahadevan, S. F. J. LeGrice, and A. Wright. 1986. Enhancement of bacterial gene expression by insertion elements or by mutations in a CAP-cAMP binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 191:85-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnetz, K. 1995. Silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter by flanking sequence elements. EMBO J. 14:2545-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnetz, K., and B. Rak. 1988. Regulation of the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by transcription antitermination. EMBO J. 7:3271-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnetz, K., and B. Rak. 1992. A mobile enhancer of transcription in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1244-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnetz, K., and J. Wang. 1996. Silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter: effects of template supercoiling and cell extracts on promoter activity in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2422-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons, R. W., B. C. Hoopes, W. R. McClure, and N. Kleckner. 1983. Three promoters near the termini of IS10: pIN, pOUT, and pIII. Cell 34:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer, M., T. A. Baker, G. Schnitzler, S. M. Deischel, M. Goel, W. Dove, K. J. Jaacks, A. D. Grossman, J. W. Erickson, and C. Gross. 1989. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 53:1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh, J., M. Mukerji, and S. Mahadevan. 1995. Transcriptional activation of the Escherichia coli bgl operon: negative regulation by DNA structural elements near the promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 17:1085-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton, A., R. Buencamino, and A. Eisenstark. 2000. rpoS mutants in archival cultures of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 182:4375-4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueguchi, C., T. Ohta, C. Seto, T. Suzuki, and T. Mizuno. 1998. The leuO gene product has a latent ability to relieve bgl silencing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:190-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visick, J. E., and S. Clarke. 1997. RpoS- and OxyR-independent induction of HPI catalase at stationary phase in Escherichia coli and identification of rpoS mutations in common laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 179:4158-4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vulic, M., and R. Kolter. 2001. Evolutionary cheating in Escherichia coli stationary phase cultures. Genetics 158:519-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waterman, S. C., and P. L. C. Small. 1996. Characterization of the acid resistance phenotype and rpoS alleles of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:2808-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weichart, D., R. Lange, N. Henneberg, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1993. Identification and characterization of stationary phase-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 10:407-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yakkundi, A., S. Moorthy, and S. Mahadevan. 1998. Reversion of an E. coli strain carrying an IS1-activated bgl operon under non-selective conditions is predominantly due to deletions within the structural genes. J. Genet. 77:21-26. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashino, T., C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific sigma factor, σS, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 14:594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zambrano, M. M., D. A. Siegele, M. Almirón, A. Tormo, and R. Kolter. 1993. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science 259:1757-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinser, E. R., and R. Kolter. 1999. Mutations enhancing amino acid catabolism confer a growth advantage in stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 181:5800-5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinser, E. R., and R. Kolter. 2000. Prolonged stationary-phase incubation selects for lrp mutations in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 182:4361-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]