Abstract

dnaE, the gene encoding one of the two replication-specific DNA polymerases (Pols) of low-GC-content gram-positive bacteria (E. Dervyn et al., Science 294:1716-1719, 2001; R. Inoue et al., Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:564-571, 2001), was cloned from Bacillus subtilis, a model low-GC gram-positive organism. The gene was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. The purified recombinant product displayed inhibitor responses and physical, catalytic, and antigenic properties indistinguishable from those of the low-GC gram-positive-organism-specific enzyme previously named DNA Pol II after the polB-encoded DNA Pol II of E. coli. Whereas a polB-like gene is absent from low-GC gram-positive genomes and whereas the low-GC gram-positive DNA Pol II strongly conserves a dnaE-like, Pol III primary structure, it is proposed that it be renamed DNA polymerase III E (Pol III E) to accurately reflect its replicative function and its origin from dnaE. It is also proposed that DNA Pol III, the other replication-specific Pol of low-GC gram-positive organisms, be renamed DNA polymerase III C (Pol III C) to denote its origin from polC. By this revised nomenclature, the DNA Pols that are expressed constitutively in low-GC gram-positive bacteria would include DNA Pol I, the dispensable repair enzyme encoded by polA, and the two essential, replication-specific enzymes Pol III C and Pol III E, encoded, respectively, by polC and dnaE.

Various analyses of the DNA polymerases (Pols) of low-GC-content gram-positive (Gr+) eubacteria have identified three enzymes which are constitutively expressed in this class of organisms (1, 3, 9, 10, 16, 20). In Bacillus subtilis, one of the most thoroughly studied of the low-GC Gr+ organisms, these Pols include: (i) Pol I, a dispensable repair enzyme encoded by polA (20); (ii) Pol III, an indispensable, replication-specific enzyme encoded by polC (10); and (iii) Pol II, an enzyme of unknown function and genetic origin that has been widely assumed (1, 3, 9, 10, 13) to be the equivalent of its namesake, E. coli Pol II (17).

Since its initial characterization (10, 16), polC-specific Pol III has been assumed to be the only Pol required for DNA replication in low-GC Gr+ eubacteria (10, 13). However, as Dervyn et al. (7) and Inoue et al. (12) have recently demonstrated for B. subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively, DNA replication in low-GC Gr+ organisms requires a second member of the Pol III primary structural family (4), a dnaE-encoded enzyme closely related to the dnaE-specific Pol IIIs required for chromosome replication in Gr-negative and high-GC Gr+ eubacteria (8, 13). Given this newfound replicative role for the low-GC Gr+ dnaE-specific product, we have sought to identify its native form in an appropriate low-GC Gr+ host. Specifically, we have exploited B. subtilis as a model organism to address the following questions: is the native dnaE product a novel enzyme, or is it Pol II, the enzyme long assumed to be the equivalent of E. coli Pol II (9, 10)? Our experiments indicate that the dnaE product is, indeed, the so-called Pol II. The results of these experiments are described below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was from EM Science, and Lennox broth (LB) was from Difco. Kanamycin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2-mercaptoethanol (BME), iminodiacetic acid-agarose (IMAC agarose), Triton X-100, and imidazole were from Sigma. Protein A-Sepharose, Mono-Q HR16/10, and phenyl Sepharose CL-4B were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

B. subtilis strain F2 (10), the source of B. subtilis Pol II and genomic DNA used to clone dnaE, was provided by Nicholas Cozzarelli. The expression plasmid pSGA04 and its host, E. coli SG101 (11), were provided by John Lowenstein. The cloning plasmid pBSm13+ (KS) was from Stratagene. Oligonucleotides used as PCR primers were synthesized and supplied by Operon, Inc. Recombinant histidine-tagged B. subtilis Pol III was a Mono-Q fraction produced and purified in this lab as described by Barnes et al. (2).

Enzyme assay.

Pol activity was assayed by using the method described by Gass and Cozzarelli (10), with [3H]TTP as the labeled substrate and nuclease-activated calf thymus DNA as the template:primer. In this assay, 1 U of activity is defined as the amount catalyzing the incorporation of 10 nmol of total nucleotide in 30 min at 37°C. Apparent inhibitor constants (Kis) of uracil-based dGTP analogs were determined in the absence of dGTP by the truncated assay method described by Wright and Brown (22). When added at a sufficient concentration to the truncated assay mixture, dGTP is specifically and fully competitive with the inhibitory actions of these analogs both to B. subtilis Pol III C and B. subtilis Pol III E.

Purification of Pol II from Pol I-deficient B. subtilis F2.

The enzyme was assayed and purified exactly as described by Gass and Cozzarelli (10). The purification was run at a scale of one-fifth of that of the original, exploiting 8 g of cell paste in the first first four steps of the procedure (step I, sonic extraction [yield, 24 ml of extract]; step II, phase partitioning; step III, ammonium sulfate precipitation; and step IV, DEAE-cellulose chromatography). The results, which were essentially identical to those reported by Gass and Cozzarelli (10), showed a step IV Pol II product with a specific activity of 28 U/mg of protein.

Cloning of B. subtilis dnaE.

The dnaE gene was cloned from B. subtilis F2 DNA as two fragments with PCR primers based on the B. subtilis genomic dnaE sequence (14) given in SubtiList (18, 19; also see the SubtiList website: http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList/). The following primer pairs were synthesized: (i) primer pair 5′a-3′a consisting of TTTTGAGCTCGAGATGTCTTTTGTTCACCTGCAAGTGCATA (SacI, XhoI) (5′a) and GGCTTCGCTCTCTGTCCAGGATTTCTTT (3′a) and (ii) primer pair 5′b-3′b consisting of GGGCGTTGTCCTGAGTGAAGAACCGTTA (5′b) and TTTAGGATCCGCATTTCTGACCTCTACTTTTGAT (BamHI) (3′b).

The respective PCR products obtained with these primers overlapped near the center of the dnaE coding sequence in a region containing a unique site for EagI. The product obtained from primer pair 5a and 3a (2,096 bp) was trimmed with SacI and EagI and cloned in a similarly digested vector [pBS(KS); Stratagene] to yield the plasmid pBSEa. The 5b-3b product (2,099 bp) was trimmed with EagI and BamHI and inserted into pBSEa downstream of the 5a-3a insert, giving rise to plasmid pBSE, containing the complete dnaE coding sequence. For expression, the dnaE sequence of pBSE was inserted into pSGA04, an expression plasmid designed to generate recombinant proteins with a removable N-terminal six-His tag (11). Specifically, pSGA04 was digested with XhoI and BamHI, and the 3,576-bp dnaE fragment, following its removal from pBSE by BamHI/XhoI digestion, was inserted into the digested plasmid to yield the expression plasmid pEXhis6:polE. Thus engineered, pEXhis6:polE specifically expresses a form of the dnaE product in which the first 6 amino acids of the enzyme's amino terminus are replaced with the following 19-residue sequence: NH2-M G H6 S G L F K R H M S R I (underlined residues denote the sequence of a cleavage site for protease Kex-2 [see reference 11]).

Growth and preparation of induced cells.

pEXhis6:polE was introduced into E. coli SG101 by transformation on LB plates containing 15 μg of kanamycin per ml and 150 μg of ampicillin per ml. Individual transformant colonies were grown at 30°C to an absorbance (600 nM; 1-cm light path) of approximately 1.0 in LB medium containing 15 μg of kanamycin per ml and 150 mg of ampicillin per ml. The culture was then cooled to 18°C, IPTG was added to 1 mM, and incubation was continued with shaking at 18°C for 18 h. The cells were chilled to 0°C, centrifuged, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.15 M NaCl; 50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.6]) containing 1 mM PMSF, and finally resuspended (30 ml of buffer per liter of centrifuged culture) in a buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5), 2 mM BME, 20% glycerol, and 1 mM PMSF.

Enzyme purification.

The following scheme summarizes purification from cells derived from 1 liter of IPTG-induced culture; all steps were performed at 4°C. Cells were fractured in a French press, and the resulting crude extract was centrifuged at ∼27,000 × g for 2 h. The resulting supernatant was loaded on a 12.5-ml column of Ni2+-charged IMAC-agarose (prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions) equilibrated with an IMAC column buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.5], 2 mM BME, 20% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF). The column was washed with 2 volumes of IMAC column buffer and eluted in a 0 to 200 mM imidazole gradient based in the same buffer but containing 10 rather than 20% glycerol (total gradient volume, 250 ml). Fractions were collected and assayed for Pol activity, and the peak fractions were pooled.

The IMAC-agarose pool was loaded directly onto a 20-ml Mono-Q fast-performance liquid chromatography column, washed with 60 ml of a buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate at pH 7.5, 5 mM BME, and 10% glycerol, and eluted with a 0.1 to 0.6 M NaCl gradient in the same buffer. The total gradient volume was 240 ml. Fractions of 2 ml were collected and assayed for Pol activity. The Pol activity and a polypeptide of the expected size (i.e., 128 to 130 kDa) coeluted in a single, sharp peak at a NaCl concentration of ∼0.4 M. The central 80% of the activity peak was pooled and used for subsequent analyses. Densitometric analysis of stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAG) electropherograms of this pool indicated that the dnaE-specific polypeptide was >95% pure. In sum, the above scheme yielded an overall purification of approximately 50-fold, with a recovery in the Mono-Q pool of approximately 50% of the recombinant Pol activity present in the crude extract.

Preparation of antibodies against the recombinant products of B. subtilis dnaE and B. subtilis polC.

Polyclonal antibody specific for each recombinant enzyme was raised in New Zealand White rabbits at Immuno-Dynamics, Inc., La Jolla, Calif. The antigen was either the Mono-Q-purified recombinant dnaE protein described above (purity, >95%) or homogeneous recombinant polC protein prepared as described by Barnes et al. (2). Following the collection of an appropriate sample of preimmune serum, each rabbit was injected intradermally with 0.2 mg of antigen in Freund's complete adjuvant. At 2, 4, and 6 weeks thereafter, each rabbit was given a booster dose by an intramuscular injection of 0.1 mg of antigen in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. Preimmune immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immune IgG were isolated from the respective sera with protein A-Sepharose by using the procedure provided by the manufacturer.

Immunosequestration assay.

Although the dnaE- and polC-specific IgGs strongly bound the corresponding recombinant protein (see the section on calibration for Western blot analysis, below), neither of them significantly neutralized its Pol activity. Therefore, the specificities and effects of the IgGs were assessed in an assay exploiting protein A-agarose to sequester the IgG-enzyme complex from solution. In this assay, appropriately diluted target enzyme was mixed with an equal amount of either a preimmune or immune IgG stock solution (both were 2 mg/ml) and incubated at 25°C for 15 min. The IgG-Pol mixture was then mixed with an equal volume of a 50% suspension of protein A-agarose in PBS and incubated for an additional 15 min at 25°C. The samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 10,000 × g to pellet the agarose, and the supernatant was retained and assessed for polymerase activity. Relative to controls run without IgG, the samples run with preimmune IgGs displayed no significant sequestration of Pol activity.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Enzyme samples were denatured and subjected to SDS-PAG electrophoresis (PAGE) as described by Laemmli (15) by using PAGEr 4 to 20% Gold Precast gels (Bio Whittaker Molecular Applications). For detection of protein by staining, gels were washed with distilled water and stained with Coomassie blue-based EZBlue reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For Western blot analysis, proteins were electrophoretically transferred from the gels to a Biotrace polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Pall Corporation) in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol) for 2 h with 100 V of constant current. Membranes were then blocked in blocking buffer (PBS, 2% dry milk, 0.2% Tween 20) for 1 h at 25°C with shaking. Membranes were then exposed to preimmune or immune rabbit IgG at a concentration of 2 mg/ml in the blocking buffer and incubated for 1 h at 25°C with shaking. Following incubation, the membranes were extensively washed with six changes (500 ml/membrane) of PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20. The membranes were then reacted with a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (Promega) in blocking buffer for 1 h at 25°C with shaking. Following incubation, the membranes were again extensively washed with six changes (500 ml/membrane) of PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20. The membranes were exposed to SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and photodeveloped on BioMax Light film (Kodak).

Preliminary calibration of IgG efficacy in Western blotting.

To calibrate the IgGs for possible use in Western blotting analysis, we carried out preliminary experiments in which diluted (1:5), SDS-denatured samples of the Pol II and Pol III peaks shown in Fig. 1 were dot blotted onto a polyvinyl difluoride membrane and probed as described above with 2-μg/ml solutions of each of the four IgGs (i.e., anti-Pol III E and its preimmune IgG and anti-Pol III C and its preimmune IgG). The results indicated that the anti-Pol III IgGs were highly enzyme specific. The anti-Pol III C-specific IgG reacted strongly with the Pol III peak and displayed a very low level of reactivity versus that of the Pol II peak, a level equivalent to that of its preimmune IgG. Similarly, the anti-Pol III E-specific IgG reacted strongly with the Pol II peak and displayed a level of reactivity versus that of the pol III peak no greater than that of its preimmune IgG.

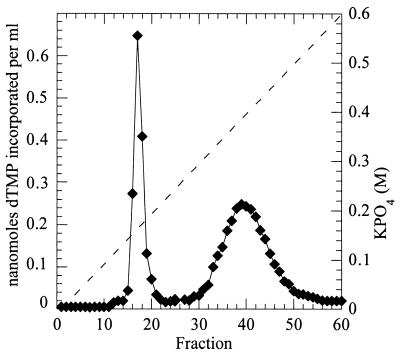

FIG. 1.

Separation of native B. subtilis Pol II and Pol III by DEAE-cellulose chromatography. The DNA Pols were extracted and copurified from an extract of the Pol I-deficient F2 strain exactly as described by Gass and Cozzarelli (10). The chromatogram represents step IV of this procedure (see Materials and Methods). Left peak, Pol II; right peak, Pol III. The Pol activity (solid line) of each fraction was assessed by determining the level of incorporation of the dTMP moiety of tritium-labeled dTTP as described in Materials and Methods. The broken line denotes the calculated molarity of potassium phosphate used for gradient elution.

RESULTS

dnaE encodes a catalytically active protein.

To determine whether dnaE encodes an active Pol, we cloned the gene and engineered it for insertion into an E. coli-based plasmid vector to permit the controlled overexpression of a recombinant protein with an N-terminal hexahistidine purification tag (see Materials and Methods for the structure and details of the cloning and induction of expression). A preliminary experiment was done to determine if the recombinant construct actually yielded a catalytically active enzyme. The experiment included three relevant plasmids: (i) a vector-only negative control, (ii) the dnaE-specific recombinant, and (iii) a positive control consisting of an equivalent recombinant plasmid construct expressing B. subtilis polC (2). The negative (vector-only) and the positive (polC recombinant) control extracts displayed the expected level of specific Pol activity (2), while the dnaE extract displayed very high specific Pol activity, a level approximately four times that of the polC-specific control.

The deduced molecular size of the six-His-tagged dnaE protein is 127.9 kDa. To determine whether the dnaE-specific extract contained a unique protein of this size, we subjected it and the negative-control (vector) extract to SDS-PAG analysis. The results (not shown) clearly indicated that the dnaE-specific extract contained a robust band of a novel protein migrating at the position expected for a 125- to 130-kDa polypeptide. When this dnaE-specific extract was subjected to the chromatographic purification procedure described in Materials and Methods, this peptide consistently coincided with Pol activity.

Identification of Pol II as the dnaE product.

After demonstrating that the dnaE product was catalytically active, we sought to determine whether it was expressed as a catalytically active protein “naturally” in its host. Because Pol II (9, 10) was the most likely candidate to be the dnaE product, we isolated Pol II from a relevant B. subtilis extract and compared it to the purified recombinant enzyme by examining selected catalytic properties, their antigenic structures, and their susceptibilities to Pol III-specific inhibitors.

For the isolation of native B. subtilis Pol II, we exploited the Pol I-negative strain and the purification procedure used by Gass and Cozzarelli (10) in their original demonstration of B. subtilis Pols II and III. The DEAE-cellulose chromatogram generated in step IV of this procedure is shown in Fig. 1. The profile of Pol activity, which closely resembled that found by Cozzarelli and Gass (10), displayed two distinct peaks, the first representing the activity of Pol II and the second representing the activity of Pol III.

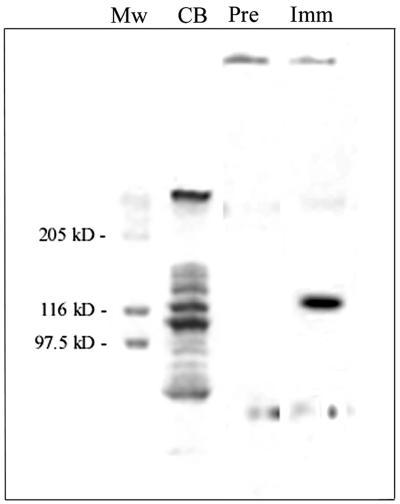

The peak fraction of the Pol II activity, as expected, was not sufficiently pure to directly distinguish the putative Pol II polypeptide (see lane CB of the SDS-PAG electropherogram shown in Fig. 2). Therefore, it was examined by Western blot analysis (see Materials and Methods for details of the procedure) with polyclonal IgG raised in a rabbit against purified recombinant dnaE enzyme (see Materials and Methods for details of the preparation). The results, which are summarized in the rightmost two lanes of Fig. 2, revealed a strong immunoreactive band at the position corresponding to approximately 125 kDa, the molecular mass expected for the full-length natural dnaE product.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of native B. subtilis Pol II. The peak fraction (fraction 16) of the chromatogram shown in Fig. 1 was processed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods; approximately 50 μg of protein was loaded in each lane. Lane MW, molecular mass standards; lane CB, Coomassie blue-stained protein; lane Pre, Western blotted sample versus preimmune IgG; lane Imm, Western blotted sample versus immune (anti-dnaE product) IgG.

Table 1 summarizes experiments that compared several essential properties of the dnaE-specific recombinant enzyme and the native B. subtilis Pol II and, as appropriate, selected properties of the so-called Pol III (i.e., the B. subtilis polC product). The dnaE product displayed the same degree of salt sensitivity and temperature dependence as native Pol II. Similarly, a polyclonal IgG raised against a highly purified form of the dnaE-specific recombinant Pol also specifically reacted with Pol II (see Materials and Methods for details of the preparation and characterization of the IgGs specific for the polC- and dnaE-specific proteins). The native Pol II and the recombinant dnaE Pol also reacted identically to representatives of two classes of our uracil-based inhibitory dGTP analogs (3, 5, 21), displaying (i) sensitivity to DCBAU [6-(3,4-dichlorobenzylamino)uracil], a 6-benzyl derivative reactive for both the polC and the dnaE recombinant products (3, 5), and (ii) essentially complete resistance to the Pol III-specific 6-anilino derivative EMAU [6-(3-ethyl-4-methylanilino)uracil] (21).

TABLE 1.

Native Pol II versus the recombinant product of dnaE

| Enzymea | Optimal ionic strength (mM)b | Activity ratio (56°C/37°C)c | Reactivity (% of Pol activity sequestered) against:d

|

Ki value (μM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimmune IgG | Anti-dnaE-Pol IgG | Anti-PolC IgG | EMAU | DCBAU | |||

| Native Pol IIe | 100 | 1.9 | <1 | 94 | <1 | NSf | 0.65 |

| dnaE productg | 100 | 1.8 | <1 | 92 | <1 | NS | 0.7 |

| polC producth | 15 | 0.12 | <1 | <1 | 95 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Enzymes were assayed under standard assay conditions as described in Materials and Methods.

KCl; assay performed as described in reference 10.

Thirty-minute assay as described in reference 10.

Sequestration as an IgG-protein complex on protein A-agarose as described in Materials and Methods.

Fraction 16 (peak) of the DEAE-cellulose chromatogram shown in Fig. 1.

NS, not sensitive; indicates a Ki value of >0.5 mM.

Mono-Q pool; see Materials and Methods for the method of preparation.

Recombinant Pol III, fraction III (Mono-Q); see Materials and Methods for the method of preparation.

DISCUSSION

The analysis of the recombinant product of B. subtilis dnaE described in Results and Materials and Methods clearly indicates that this gene encodes a catalytically active DNA Pol with the molecular weight expected for the full-length gene product. The finding of Pol activity in this dnaE product is consistent with that of Bruck and O'Donnell (6), who demonstrated a catalytically active recombinant form of the dnaE product of another low-GC Gr+ eubacterium, Streptococcus pyogenes, and it is also consistent with our recent expression of a catalytically active recombinant form of dnaE from a third low-GC Gr+ bacterium, Enterococcus fecalis (M. Barnes, K. Foster, and N. Brown, unpublished results).

The recombinant B. subtilis dnaE Pol and the naturally derived B. subtilis enzyme known as Pol II have the same catalytic, antigenic, and physical properties (Table and Fig. 2) and a pattern of reactivity identical to that of the 6-anilino- and 6-benzyl-uracil inhibitors (Table 1). In sum, our findings clearly demonstrate that the recombinant product of B. subtilis dnaE and the constitutively expressed B. subtilis Pol II are one and the same.

How do these results with B. subtilis dnaE apply to the rest of the membership of the low-GC class of Gr+ eubacteria? The widespread incidence of a dnaE-like gene in these low-GC Gr+ organisms clearly suggests that they apply broadly to this class, and our work with several other members of the class strongly supports that suggestion. For example, we have found that application of the B. subtilis Pol II-Pol III purification scheme (10) to the crude extracts of Enterococcus fecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, and three other bacilli (i.e., B. licheniformis, B. pumilis, and B. megaterium) consistently yields, in step IV, the Pol II-Pol III elution pattern found for B. subtilis (1, 3; M. Barnes and N. Brown, unpublished results). Further, the Pol “II” and Pol III peaks of these organisms also display the same pattern of reactivity to the DCBAU- and EMAU-based inhibitors.

Our results also finally resolve two inconsistencies that have arisen from the long-standing assumption that the low-GC Gr+-specific Pol II is the equivalent of E. coli Pol II (9, 10, 17). The first inconsistency is the striking difference noted in the physical and catalytic properties of the B. subtilis and E. coli enzymes (10, 13, 17). The second is the absence from the B. subtilis genome of a gene encoding a protein with the canonical family B-type primary structure of E. coli Pol II (4, 13, 17, 18, 19).

With the identification of Pol II as the dnaE product, the three Pols constitutively expressed by low-GC Gr+ bacteria are as follows: (i) Pol I, the product of polA and a member of the primary structural Pol family A (4, 10, 20); (ii) Pol III, the product of polC and a member of the replication-specific Pol III family (4, 10); and (iii) the dnaE-encoded “Pol II” enzyme. Considering the fact that both of the enzymes encoded by polC and dnaE are members of the replication-specific Pol III primary structural family (4), we propose that, henceforth, each be given the Pol III designation and the suffix C or E to denote the gene from which it originates, i.e., Pol III C for the polC product and Pol III E for the dnaE product.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grant GM45330 from the USPHS, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes, M., and N. Brown. 1979. Antibody to B. subtilis DNA polymerase III: use in enzyme purification and examination of homology among replication-specific DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 6:1202-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes, M., C. Leo, and N. Brown. 1998. DNA polymerase III of Gram-positive Eubacteria is a zinc metalloprotein conserving an essential finger-like domain. Biochemistry 37:15254-15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, M., P. Tarantino, Jr., P. Spacciapoli, N. Brown, H. Yu, and K. Dybvig. 1994. DNA polymerase III of Mycoplasma pulmonis: isolation and characterization of the enzyme and its structural gene, polC. Mol. Microbiol. 13:843-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braithwaite, D., and J. Ito. 1993. Compilation, alignment, and phylogenetic relationships of DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:787-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, N., J. Gambino, and G. Wright. 1977. Inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III: 6-(arylalkylamino)-uracils and 6-anilinouracils. J. Med. Chem. 20:1186-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruck, I., and M. O'Donnell. 2000. The DNA replication machine of a Gram-positive organism. J. Biol. Chem. 275:28971-28983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dervyn, E., C. Suski, R. Daniel, C. Bruand, J. Chapuis, J. Errington, L. Janniere, and S. Ehrlich. 2001. Two essential DNA polymerases at the bacterial replication fork. Science 294:1716-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flett, F., D. Jungman-Campello, V. Mersinias, S. Koh, R. Godden, and C. Smith. 1999. A “Gram-negative-type” DNA polymerase III is essential for replication of the linear chromosome of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 31:949-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesan, A., C. Yehle, and C. Yu. 1973. DNA replication in a polymerase I-deficient mutant and the identification of DNA polymerases II and III in Bacillus subtilis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 50:155-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gass, K., and N. Cozzarelli. 1973. Further genetic and enzymological characterization of the three Bacillus subtilis deoxyribonucleic acid polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 248:7688-7700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh, S., and J. Lowenstein. 1996. A multifunctional vector system for heterologous expression of proteins in Escherichia coli: expression of native and hexahistidyl fusion proteins, rapid purification of the fusion proteins, and removal of fusion peptide by Kex2 protease. Gene 176:249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue, R., C. Kaito, M. Tanabe, K. Kamura, N. Akimitsu, and K. Sekimizu. 2001. Genetic identification of two distinct DNA polymerases, DnaE and PolC, that are required for chromosomal replication in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:564-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornberg, A., and T. Baker. 1992. Prokaryotic DNA polymerases other than E. coli pol I, p. 161-196. In A. Kornberg and T. Baker, DNA replication, 2nd ed. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, N.Y.

- 14.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, L. Moszer, A. Abertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low, R., S. Rashbaum, and N. Cozzarelli. 1976. Purification and characterization of DNA polymerase III from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 251:1311-1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moses, R., and C. Richardson. 1970. A new DNA polymerase activity of Escherichia coli. I. Purification and properties of the activity present in E. coli polA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 41:1557-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moszer, I., P. Glaser, and A. Danchin. 1995. SubtiList: a relational database for the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology 141:261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moszer, I. 1998. The complete genome of Bacillus subtilis: from sequence annotation to data management and analysis. FEBS Lett. 430:28-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okazaki, T., and A. Kornberg. 1964. Enzymatic synthesis of DNA. XV. Purification and properties of a polymerase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 239:259-268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarantino, P., M., Jr., C. Zhi, G. E. Wright, and N. C. Brown. 1999. Inhibitors of DNA polymerase III as novel antimicrobial agents against gram-positive eubacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1982-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright, G., and N. Brown. 1976. The mechanism of inhibition of B. subtilis DNA polymerase III by 6-(arylhydrazino)-pyrimidines: novel properties of 2-thiouracil derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 432:37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]