Abstract

Burkholderia thailandensis is a nonpathogenic gram-negative bacillus that is closely related to Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei. We found that B. thailandensis E125 spontaneously produced a bacteriophage, termed φE125, which formed turbid plaques in top agar containing B. mallei ATCC 23344. We examined the host range of φE125 and found that it formed plaques on B. mallei but not on any other bacterial species tested, including B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei. Examination of the bacteriophage by transmission electron microscopy revealed an isometric head and a long noncontractile tail. B. mallei NCTC 120 and B. mallei DB110795 were resistant to infection with φE125 and did not produce lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O antigen due to IS407A insertions in wbiE and wbiG, respectively. wbiE was provided in trans on a broad-host-range plasmid to B. mallei NCTC 120, and it restored LPS O-antigen production and susceptibility to φE125. The 53,373-bp φE125 genome contained 70 genes, an IS3 family insertion sequence (ISBt3), and an attachment site (attP) encompassing the 3′ end of a proline tRNA (UGG) gene. While the overall genetic organization of the φE125 genome was similar to λ-like bacteriophages and prophages, it also possessed a novel cluster of putative replication and lysogeny genes. The φE125 genome encoded an adenine and a cytosine methyltransferase, and purified bacteriophage DNA contained both N6-methyladenine and N4-methylcytosine. The results presented here demonstrate that φE125 is a new member of the λ supergroup of Siphoviridae that may be useful as a diagnostic tool for B. mallei.

The disease glanders is caused by Burkholderia mallei, a host-adapted pathogen that does not persist in nature outside of its horse host (32). Glanders is a zoonosis, and humans whose occupations put them into close contact with infected animals can contract the disease. There have been no naturally occurring cases of glanders in North America in the last 60 years, but laboratory workers are still at risk of infection with B. mallei via cutaneous (68) and inhalational (31) routes. Human glanders has been described as a painful and loathsome disease from which few recover without antibiotic intervention (33, 51). There is little known about the virulence factors of this organism, but a recent report indicates that the capsular polysaccharide is essential for virulence in hamsters and mice (24).

Burkholderia pseudomallei is the etiologic agent of the glanders-like disease melioidosis (21). As the names suggest, B. mallei and B. pseudomallei are closely related species (19, 56, 59, 69). These β-Proteobacteria can now be directly compared at the genomic level because the B. pseudomallei K96243 genomic sequence is available at the Sanger Institute website (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/) and the B. mallei ATCC 23344 genomic sequence is available at the TIGR (The Institute for Genomic Research) website (http://www.tigr.org/). Preliminary BLAST (4) comparisons indicate that the genes conserved between these species are ∼99% identical at the nucleotide level. This high level of nucleotide identity makes it challenging to use nucleic acid-based assays to discriminate between B. mallei and B. pseudomallei (6, 71).

There are legitimate concerns that B. mallei and B. pseudomallei may be misused as biological weapons (16, 46, 51, 60), and there is compelling evidence that B. mallei has already been used in this manner (3, 74). Diagnostic assays should be developed to discriminate between these microorganisms in the event that they are misused in the future. The use of a combination of diagnostic assays may be necessary to discriminate between these species, including nucleic acid-based assays, phenotypic assays (colony morphology, motility, and carbohydrate utilization), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, intact cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight, and bacteriophage susceptibility.

In 1957 Smith and Cherry described eight lysogenic B. pseudomallei strains that produced bacteriophage that were more active on B. mallei than on B. pseudomallei (67). In fact, bacteriophage E attacked B. mallei strains exclusively. Manzenink et al. (45a) found that 91% of their B. pseudomallei strains were lysogenic and that three bacteriophages, PP19, PP23, and PP33, could be used in combination to identify B. mallei. Unfortunately, these B. mallei-specific bacteriophage were not further characterized and are not readily available. It is interesting that neither study identified bacteriophage production by B. mallei strains.

The purpose of this work was to identify and characterize a B. mallei-specific bacteriophage and make it available to the scientific community. Burkholderia thailandensis is a nonpathogenic soil saprophyte that has been described as B. pseudomallei-like (9, 10), and there are no published reports describing bacteriophage production by this species. B. thailandensis E125, isolated in 1991 from soil in northeastern Thailand (70), spontaneously produced a temperate bacteriophage (φE125) that attacked B. mallei but not any other bacterial species examined. The gene order and modular organization of the φE125 genome is reminiscent of lambdoid bacteriophages (11, 34), and it contains several interesting features, including an insertion sequence, two DNA methylase genes, and a novel cluster of putative replication and lysogeny genes. Bacteriophage φE125 exhibits a B1 morphotype and therefore is a new member of the family Siphoviridae (phage with long noncontractile tails) (1, 2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial plasmids, strains, and growth conditions.

The plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. The B. mallei strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. The following B. pseudomallei strains were used in this study: 316c, NCTC 4845, 1026b, WRAIR 1188, USAMRU Malaysia 32, Pasteur 52237, STW 199-2, STW 176, STW 115-2, STW 152, STW 102-3, STW 35-1, K96243, 576a, 275, 295, 296, 503, 506, 112c, 238, 423, 465a, 776, 439a, 487, 644, 713, 730, E8, E12, E13, E24, E25, E40, E203, E210, E214, E215, E250, E272, E277, E279, E280, E283, E284, E300, E301, E302, and E304 (5, 20, 22, 25, 26, 66, 76). B. thailandensis strains E27, E30, E32, E96, E100, E105, E111, E120, E125, E132, E135, E202, E251, E253, E254, E255, E256, E257, E258, E260, E261, E263, E264, E266, E267, E275, E285, E286, E290, E293, E295, and E299 (10, 66, 76) were also utilized in this study. Other Burkholderia species used in this study include B. cepacia LMG 1222 (genomovar I) (44), B. multivorans C5568, B. multivorans LMG 18823 (44), B. cepacia LMG 18863 (genomovar III) (44), B. cepacia 715j (genomovar III) (47), B. stabilis LMG 07000, B. vietnamiensis LMG 16232 (44), B. vietnamiensis LMG 10929 (44), B. gladioli 2-72 (62), B. gladioli 2-75 (62), B. gladioli 4-54 (62), B. gladioli 5-62 (62), B. uboniae EY 3383 (77), B. cocovenans ATCC 33664, B. pyrrocinia ATCC 15958, B. glathei ATCC 29195, B. caryophylli Pc 102, B. andropogonis PA-133, B. kururiensis KP23 (79), B. sacchari IPT101 (8), Burkholderia sp. strain 2.2N (13), and Burkholderia sp. strain T-22-8A. Ralstonia solanacearum FC228, R. solanacearum FC229, R. solanacearum FC230, Pandoraea apista LMG 16407 (17), Pandoraea norimbergensis LMG 18379 (17), Pandoraea pnomenusa LMG 18087 (17), Pandoraea pulmonicola LMG 18106 (17), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia XM16 (39), S. maltophilia XM47 (39), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO (30), P. aeruginosa PA14 (55), Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 (73), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (29), Serratia marcescens H11, Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen), S17-1λpir (65), HB101 (7), MC4100 (15), DH5α (Gibco BRL), JM105 (78), E2348/69 (41), and DB24 (36) were also used in this study. E. coli was grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (Lennox) or in LB broth (Lennox). P. syringae, B. andropogonis, Burkholderia sp. strain 2.2N, Burkholderia sp. strain T-22-8A, B. glathei, and B. caryophylli were grown at 25°C on LB agar or in LB broth containing 4% glycerol. All other bacterial strains were grown at 37°C on LB agar or in LB broth containing 4% glycerol. When appropriate, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 100 μg of ampicillin, 30 μg of chloramphenicol, 25 μg of kanamycin, and 15 μg of tetracycline per ml for E. coli and 100 μg of streptomycin and 50 μg of tetracycline per ml for B. thailandensis. B. mallei DD3008 was grown in the presence of 5 μg of gentamicin per ml, and B. mallei NCTC 120 (pBHR1) was grown in the presence of 15 μg of polymyxin B and 5 μg of kanamycin per ml.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript KS | General cloning vector; ColE1; Apr | Stratagene |

| pDW1 | pBluescript KS containing 1,068-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW3.2 | pBluescript KS containing 3,231-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW4.4 | pBluescript KS containing 4,351-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW5.5 | pBluescript KS containing 5,448-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW7.5 | pBluescript KS containing 7,325-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW9.5 | pBluescript KS containing 9,025-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW11 | pBluescript KS containing 9,942-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pDW18 | pBluescript KS containing 12,983-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 | This study |

| pSKM11 | Positive selection cloning and suicide vector; IncP oriT; ColE1 ori; Apr Tcs | 50 |

| pSKM3.2 | pSKM11 containing 3,231-bp HindIII fragment from φE125; Apr Tcr | This study |

| pDD5003B | 37.4-kb BamHI fragment from DD5003 obtained by self-cloning; Apr Tcr | This study |

| pCR2.1 | 3.9-kb TA cloning vector; pMB1 oriR; Kmr Apr | Invitrogen |

| pAM1 | pCR2.1 containing φE125 gene27 downstream of the lac promoter | This study |

| pCM1 | pCR2.1 containing φE125 gene56 downstream of the lac promoter | This study |

| pDD70 | pCR2.1 containing 3.2-kb NCTC 120 wbiE::IS407A PCR fragment | This study |

| pDD71 | pCR2.1 containing 3.2-kb DB110795 wbiG::IS407A PCR fragment | This study |

| pDD72 | pCR2.1 containing ATCC 23344 wbiE | This study |

| pSPORT 1 | General cloning vector; ColE1; Apr | Life Technologies |

| pSPORT 8.1 | pSPORT 1 containing 8.1-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pDD5003B | This study |

| pBHR1 | Mobilizable broad-host-range vector; Kmr Cmr | MoBiTec |

| pBHR1-wbiE | pBHR1 containing 1.8-kb EcoRI fragment from pDD72; Kmr Cms | This study |

Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin; Tc, tetracycline; Km, kanamycin; Cm, chloramphenicol.

TABLE 2.

Bacteria used to examine the host range of bacteriophage φE125

| Bacterium | Relevant information | Plaque formationa |

|---|---|---|

| Burkholderia mallei | ||

| NCTC 120 | LPS O-antigen mutant; wbiE::IS407A | − |

| NCTC 10248 | + | |

| NCTC 10229 | + | |

| NCTC 10260 | + | |

| NCTC 10247 | + | |

| NCTC 3708 | + | |

| NCTC 3709 | + | |

| ATCC 23344 | + | |

| ATCC 10399 | + | |

| ATCC 15310 | + | |

| DB110795 | Laboratory-passaged ATCC 15310; LPS O-antigen mutant; wbiG::IS407A | − |

| BML10 | ATCC 23344 (φE125) | − |

| DD3008 | ATCC 23344::pGSV3008; capsule mutant | + |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | 50 strains | − |

| Burkholderia thailandensis | 32 strains | − |

| Burkholderia cepacia | Genomovar I; 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia multivorans | 2 strains | − |

| Burkholderia cepacia | Genomovar III; 2 strains | − |

| Burkholderia stabilis | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | 2 strains | − |

| Burkholderia gladioli | 4 strains | − |

| Burkholderia uboniae | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia cocovenans | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia pyrrocinia | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia glathei | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia caryophylli | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia andropogonis | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia kururiensis | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia sacchari | 1 strain | − |

| Burkholderia spp. | 2 strains | − |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | 3 strains | − |

| Pandoraea apista | 1 strain | − |

| Pandoraea norimbergensis | 1 strain | − |

| Pandoraea pnomenusa | 1 strain | − |

| Pandoraea pulmonicola | 1 strain | − |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 strains | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2 strains | − |

| Pseudomonas syringae | 1 strain | − |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | 1 strain | − |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 strain | − |

| Escherichia coli | 8 strains | − |

+, present; −, absent.

Spontaneous bacteriophage production by lysogenic B. thailandensis strains and UV induction experiments.

B. thailandensis strains E264, E275, E202, E125, and E251 were grown in LB broth for 18 h at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm). One hundred microliters of each saturated culture was used to inoculate two LB broth (3-ml) subcultures. One set of subcultures was incubated for 5 h under the same conditions. The other set of subcultures was incubated for 3 h, poured into sterile petri dishes in a class II biological safety cabinet, subjected to a hand-held UV light source (254 nm) for 20 s (25 cm above the sample), pipetted back into culture tubes, and incubated for an additional 2 h. Both sets of subcultures were briefly centrifuged to pellet the cells, and the supernatants were filter sterilized (0.45-μm-pore-size filters). The samples were serially diluted in suspension medium (SM) (40), and the numbers of PFU were assessed by using B. mallei ATCC 23344 as the host strain as described below. Bacteriophage was considered to be induced if the titer increased twofold (or more) after exposure to UV light. If bacteriophage titers did not increase twofold, the bacteriophage was not considered to be induced by UV light.

Bacteriophage φE125 propagation and DNA purification.

The protocols followed for picking plaques, titrating bacteriophage stocks, and preparing plate lysates were the same as those used for bacteriophage λ (61), with a few minor modifications. Briefly, 0.1 ml of φE125 and 0.1 ml of a saturated culture of B. mallei ATCC 23344 (∼5 × 108 bacteria) were mixed and incubated at 25°C for 20 min, and 4.8 ml of molten LB top agar (0.7%) containing 4% glycerol was added. The mixture was immediately poured onto LB plates containing 4% glycerol and incubated overnight at 37°C. For preparation of plate lysate stocks, 5 ml of SM was added to the plate, and bacteriophage was eluted overnight at 4°C without shaking. SM was harvested, bacterial debris was separated by centrifugation, and the resulting supernatant was filter sterilized (0.45-μm-pore-size filters) and stored at 4°C. Bacteriophage φE125 DNA was purified from a plate culture lysate using the Wizard Lambda Preps DNA Purification System (Promega). The φE125 lysogen BML10 was isolated from a single turbid plaque formed on ATCC 23344. The plaque was picked with a Pasteur pipette, transferred to a tube containing 3 ml of broth media, and incubated overnight. The saturated culture was spread onto solid media with an inoculating loop, and 10 isolated colonies were tested for their ability to form plaques with φE125. All of the colonies were resistant to infection with φE125, and one was selected and designated BML10.

φE125 sensitivity testing.

Approximately 102 PFU was added to a saturated bacterial culture and incubated at 25°C for 20 min, and 4.8 ml of molten LB top agar (0.7%) containing 4% glycerol was added. The mixture was immediately poured onto a LB plate containing 4% glycerol and incubated overnight at 25 or 37°C, depending on the bacterial species being tested. Bacteria were considered to be sensitive to φE125 if they formed plaques under these conditions and resistant if they did not. It should be noted that the positive control, B. mallei ATCC 23344, formed plaques in the presence of φE125 after incubation at 25 and 37°C. No bacterial species tested formed plaques in the absence of φE125.

Negative staining of φE125.

Bacteriophage φE125 was prepared from 20 ml of a plate culture lysate (see above), incubated at 37°C for 15 min with Nuclease Mixture (Promega), precipitated with Phage Precipitant (Promega), and resuspended in 1 ml of Phage Buffer (Promega). The bacteriophage solution (∼100 μl) was added to a strip of parafilm M (Sigma), and a formvar-coated nickel grid (400 mesh) was floated on the bacteriophage solution for 30 min at 25°C. Excess fluid was removed, and the grid was placed on a drop of 1% phosphotungstic acid, pH 6.6, for 2 min at 25°C. Excess fluid was removed, and the specimen was examined on a Philips CM100 transmission electron microscope. Nickel grids were glow discharged on the day of use.

DNA manipulation and plasmid conjugation.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments used in cloning procedures were excised from agarose gels and purified with a GeneClean III Kit (Bio 101). Bacterial genomic DNA was prepared by using the Masterpure DNA Kit (Epicentre) for methylase dot blot assays and by a previously described protocol (75) for all other experiments. Plasmids were purified from overnight cultures using Wizard Plus SV Minipreps (Promega). The broad-host-range plasmids pBHR1 and pBHR1-wbiE were electroporated into E. coli S17-1λpir (12.25 kV/cm) and conjugated to B. mallei NCTC 120 for 8 h as described elsewhere (22). Similarly, the suicide vector pSKM3.2 was electroporated into E. coli S17-1λpir and conjugated to B. thailandensis E125 for 8 h as described elsewhere (22). The resulting strain, B. thailandensis DD5003, contained pSKM3.2 integrated into the φE125 genome at the 3.2-kb HindIII fragment. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from DD5003 and digested with the restriction endonuclease BamHI, and the bacteriophage attachment site and flanking bacterial DNA were obtained by self-cloning (22).

Immunoblot analysis.

Fifty microliters of a saturated broth culture of B. mallei was subjected to centrifugation, and the bacterial pellet was washed with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. The sample was resuspended in 50 μl of sample buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.005% bromphenol blue in Tris buffer, pH 6.8) and boiled for 10 min. The sample was treated with proteinase K (25 μg dissolved in 10 μl of sample buffer) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Forty microliters of sample was boiled for 5 min, loaded onto a 4% polyacrylamide stacking gel-12% polyacrylamide separating gel, and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed using 1× Tris-Glycine SDS Running buffer (Novex). The gel was blotted to Immuno-Blot PVDF Membrane (Bio-Rad) by using a Trans-Blot SD Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The membrane was subjected to a blocking step (5% skim milk, 0.1% Tween 20) and was reacted with a 1:2,000 dilution of 3D11, a monoclonal mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody that reacts with B. mallei lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O antigen (Research Diagnostics, Inc.). Following several washing steps with blocking buffer, the membrane was reacted with a 1:5,000 dilution of peroxidase-labeled goat antibody to mouse IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc. [KPL]). Finally, it was washed three times with blocking buffer and once with PBS (pH 7.4) and then incubated with TMB Membrane Peroxidase Substrate (KPL).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed at ACGT, Inc. (Northbrook, Ill.) and at LMT Sequencing Lab (Frederick, Md.). Most φE125 genes were identified by using GeneMark.hmm (43), whereas others were identified by visual inspection, guided by BLAST (4) results. DNA and protein sequences were analyzed with GeneJockeyII and MacVector 7.1 software for the Macintosh. The gapped BLASTX and BLASTP programs were used to search the nonredundant sequence database for homologous proteins (4). In order to determine the nucleotide sequence of the φE125 cos sites, we sequenced the ends of φE125 DNA directly by using the following primers: COS4, 5′-AATCCGGCTCGTCCTTATTC-3′ and COS10, 5′-GTTGCGGTGACGTGGTGGTG-3′. The nucleotide sequences obtained contained a gap relative to the ligated φE125 ends on pDW9.5, which corresponded to unsequenceable 3′ ends (64).

PCR amplifications.

PCR products were sized by using agarose electrophoresis and cloned using the pCR2.1 TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and chemically competent E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen). PCR amplifications were performed with a final reaction volume of 100 μl and contained 1× Taq PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), 1 μM oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers, and approximately 200 ng of genomic DNA. PCR mixtures were transferred to a PTC-150 MiniCycler with a Hot Bonnet accessory (MJ Research) and heated to 97°C for 5 min. This was followed by 30 cycles of a three-temperature cycling protocol (97°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min) and one cycle at 72°C for 10 min. The eight oligodeoxyribonucleotide primer pairs used in the PCR amplification of the LPS O-antigen gene cluster were as follows: 1-1, 5′-CGAGTTCACGGTATCACAAG-3′, and 1-2, 5′-GTTGTCGTAGAAGTACAGCC-3′; 2-1, 5′-GGCTGTACTTCTACGACAAC-3′, and 2-2, 5′-GCATCAGCAGCGGATTGAAG-3′; 3-1, 5′-CTTCAATCCGCTGCTGATGC-3′, and 3-2, 5′-GAATGCGACTTCAACAACAC-3′; 4-1, 5′-GTGTTGTTGAAGTCGCATTC-3′, and 4-2, 5′-CATAAACGTTCTGCAGACGC-3′; 5-1, 5′-GCGTCTGCAGAACGTTTATG-3′, and 5-2, 5′-GATTTGCTGCAAATAGCGTG-3′; 6-1, 5′-CACGCTATTTGCAGCAAATC-3′, and 6-2, 5′-CGAAGATATCGAGCCAGTGC-3′; 7-1, 5′-GCACTGGCTCGATATCTTCG-3′, and 7-2, 5′-CCGAAGCGGTTGAAGAAGTG-3′; 8-1A, 5′-CTGGAAATGGCTATGAGCAG-3′, and 8-2A, 5′-AAATGCTCGCGTCATGTTGC-3′.

In order to determine the order and orientation of the HindIII fragments in the intact φE125 genome, outward-oriented primers specific for the ends of each HindIII fragment (except the 1,068-bp fragment) were synthesized and PCR was performed with φE125 genomic DNA and all possible primer combinations. We reasoned that two HindIII fragments were adjacent if we obtained a PCR product with primer pairs specific for the corresponding ends of those fragments. All PCR products were cloned and sequenced to confirm the PCR results. For these PCRs, and all of the PCR experiments mentioned below, the conditions mentioned above were used, with the following exception: we used 72°C for 30 s instead of 72°C for 2 min in the three-temperature cycling protocol. The 14 oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers used in this analysis were as follows: 3.2F, 5′-AGACGATCAAGCAACACGAG-3′; 3.2R, 5′-TCGAAGCGCCAATAAAACGC-3′; 4.4F, 5′-CAAGCTCTCTCAGCTTCTCG-3′; 4.4R, 5′-ACCAGCGGCCATACATTATG-3′; 5.5F, 5′-GGTCTCCGGATCGTAATTGT-3′; 5.5R, 5′-TCGTGCGTCAGTTCAAATGG-3′; 7.5F, 5′-CCAGATCCAGAATACGCAAC-3′; 7.5R, 5′-ATAACGCGCTTTGTCGATCG-3′; 9.5F, 5′-GAGTGAAGCCATCGAAGATC-3′; 9.5R, 5′-ACGGAAAGGAGCATGTCATC-3′; 11F, 5′-TCATCGACGAGGAACTTCAC-3′; 11R, 5′-AATGATGGTCAGCACGAACG-3′; 18F-2, 5′-TCAAGGTAGAACAGCGTGTG-3′; 18R, 5′-GCTCCTTGTCCAAGTAGATG-3′.

PCR was performed with genomic DNAs from B. mallei ATCC 23344, B. mallei BML10, φE125, and the primers Pro (5′-TATACCCGACCGAATTGG-3′) and Int (5′-TATGACGTGAAGGCACTC-3′) to determine if φE125 integrated into the proline tRNA (UGG) gene in B. mallei. We obtained a single PCR product of the expected size (550 bp) with B. mallei BML10 DNA. This product was cloned, and its nucleotide sequence was determined. No PCR products were obtained when genomic DNAs from B. mallei ATCC 23344 or φE125 were used in the PCR.

Genomic DNA from φE125 was used for PCR amplification of gene27 with the following primers: AM-UP, 5′-CAAGTTTAAAAACGGCTTTCAC-3′, and AM-DOWN, 5′-CAGCCAATCGATCAGAACAG-3′. The resulting PCR product was cloned, sequenced, and designated pAM1 (Table 1). Similarly, gene56 was amplified by PCR using φE125 genomic DNA and the following primers: CM-UP, 5′-CACAGGTGCTGTTCAATCTC-3′, and CM-DOWN, 5′-CTCACATGACCTCCAAAACG-3′. The resulting PCR product was cloned, sequenced, and designated pCM1 (Table 1).

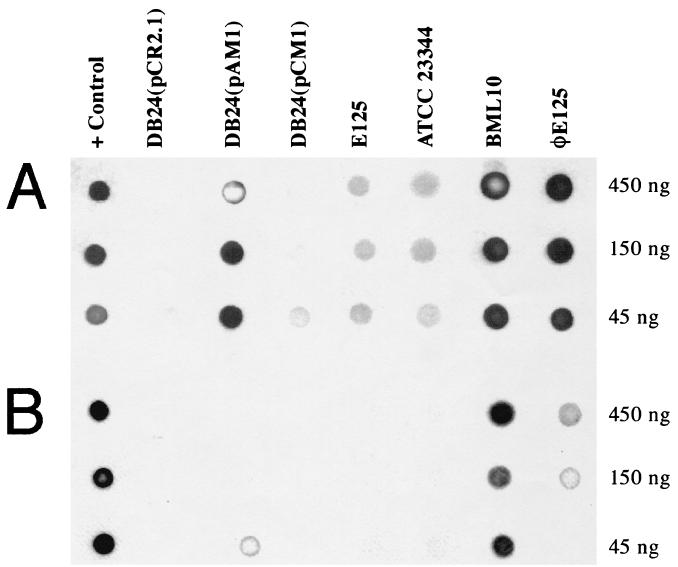

Dot blot assay for DNA methyltransferase activity.

The plasmids pCR2.1, pAM1, and pCM1 (Table 1) were electroporated into E. coli DB24, a strain that lacks all endogenous DNA methylation (36). The transformants were grown overnight in the presence of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and genomic DNA was isolated as described above. Genomic DNA preparations were diluted in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) to yield stocks of 150, 50, and 15 ng/μl, and 3-μl aliquots of each were spotted onto a BA85 nitrocellulose filter (Schleicher & Schuell). Methylase activity was assessed by using rabbit primary antibodies that react specifically with DNA containing N6-methyladenine (m6A) or N4-methylcytosine (m4C) in a dot blot assay, as described previously (36). The secondary antibody was a peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) conjugate (KPL). Primary and secondary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:50,000 and 1:1,000, respectively. Detection was accomplished by using the luminol system (Amersham/Pharmacia), and exposures were made to hyperfilm-ECL (Amersham/Pharmacia). The film images were digitally captured using a UMAX flatbed scanner (S900) and Adobe Photodeluxe (version 1.1) software for the PowerMac.

GenBank and American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers AF447491 (φE125 genome) and AY063741 (B. thailandensis bacteriophage attachment site). φE125 was deposited in the ATCC bacteriophage collection and was assigned the accession number ATCC 23344-B1.

RESULTS

B. thailandensis strains spontaneously produce bacteriophage that infect B. mallei.

Five strains of B. thailandensis (E125, E202, E251, E264, and E275) were examined for the production of B. mallei-specific bacteriophage. All of the strains, with the exception of E251, spontaneously produced bacteriophage that formed plaques with diameters of 1.5 to 2 mm on B. mallei ATCC 23344. Strain E264 produced two bacteriophages that formed distinct plaques, one turbid and one clear. Strains E125, E202, and E275 each produced a bacteriophage that formed turbid plaques. Bacteriophage production was increased 2-fold (E264 and E275), 6-fold (E125), and 55-fold (E202) by brief exposure to UV light. The clear plaque bacteriophage from E264 was not induced, and UV light did not induce bacteriophage production by E251. We examined the host range of all five B. thailandensis bacteriophages on 10 strains of B. mallei and 13 strains of B. pseudomallei and found that the temperate bacteriophages produced by E264, E202, and E275 formed plaques on 9 of 10 B. mallei strains and on 3 of 13 B. pseudomallei strains. Since these bacteriophages were not specific for B. mallei, they were not further characterized. The clear plaque bacteriophage produced by E264 (LPE264) and the temperate bacteriophage produced by E125 (φE125) formed plaques on 8 of 10 and 9 of 10 B. mallei strains, respectively. Neither bacteriophage formed plaques on B. pseudomallei or on B. mallei NCTC 120. Typical yields of plate lysate stocks of LPE264 were 105 PFU/ml, and yields of φE125 were 108 PFU/ml. Bacteriophage LPE264 was not further characterized in this study due to its low yield and its inability to form plaques on B. mallei NCTC 3709. Taken together, these results indicate that lysogenic B. thailandensis strains exist in nature and that the bacteriophage they harbor are spontaneously produced and infect B. mallei.

Bacteriophage φE125 is B. mallei specific.

The host range of φE125 was examined with 139 bacterial strains, including 13 strains of B. mallei, 50 strains of B. pseudomallei, and 32 strains of B. thailandensis (Table 2). Bacteriophage φE125 formed plaques on 9 of 10 B. mallei strains obtained from NCTC and ATCC. It also formed plaques on DD3008, a capsule-deficient mutant derived from ATCC 23344 (24). Three B. mallei strains were resistant to plaque formation by φE125, NCTC 120, DB110795 (a laboratory-passaged derivative of ATCC 15310), and BML10 (ATCC 23344 harboring the φE125 prophage).

φE125 did not form plaques on any of the B. pseudomallei or B. thailandensis strains used in this study (Table 2). It should be noted that the B. pseudomallei strains employed in this study were from a variety of sources; 15 clinical isolates, 30 Thai soil isolates, and 5 Australian soil isolates. Similarly, the B. thailandensis strains were isolated in northeastern Thailand (15 strains) and central Thailand (17 strains).

Finally, φE125 plaque formation was evaluated with 15 additional species of Burkholderia, 4 species of Pandoraea, 2 species of Pseudomonas, Ralstonia solanacearum, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Serratia marcescens, and E. coli. None of these bacteria formed plaques with bacteriophage φE125 (Table 2). These results demonstrate that bacteriophage φE125 forms plaques only on B. mallei strains, that φE125-resistant B. mallei strains exist, and that the capsular polysaccharide (24) is not required for plaque formation by φE125.

φE125 is a new member of the family Siphoviridae.

Bacteriophage may be tailed, cubic, filamentous, or pleomorphic and can be classified by morphotype and host genus (2). Numerous negatively stained bacteriophage were examined, and a representative image of φE125 is shown in Fig. 1. φE125 possessed an isometric head of 63 nm in diameter and a long noncontractile tail of 203 nm in length and 8 nm in diameter. Based on its B1 morphotype, φE125 can be classified as a member of the order Caudovirales and the family Siphoviridae (1, 2). To our knowledge, this is the first bacteriophage of the Siphoviridae family described as being harbored by the host genus Burkholderia (2).

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrograph of bacteriophage φE125 negatively stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid. Scale bar, 100 nm.

LPS O antigen is required for plaque formation by φE125.

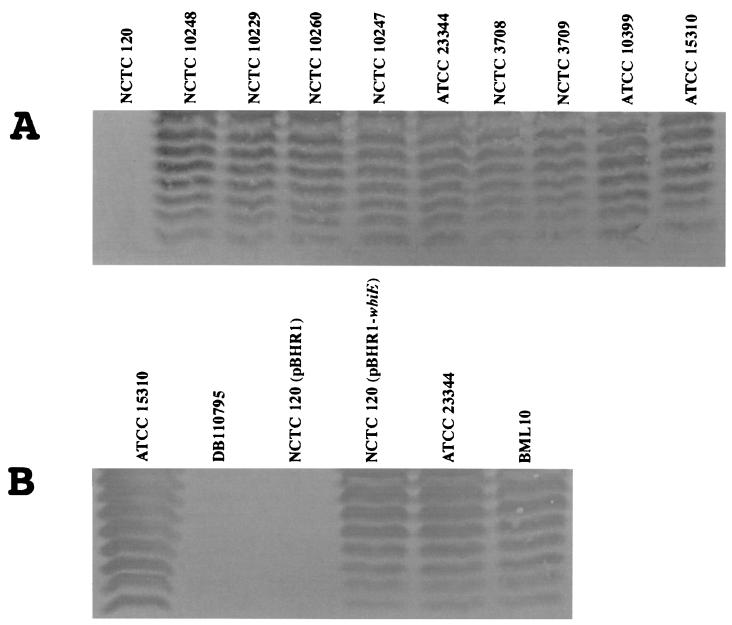

Of the 10 B. mallei strains obtained from NCTC and ATCC, only NCTC 120 was resistant to plaque formation by φE125 (Table 2). We hypothesized that resistance was due to the absence of a surface receptor for φE125 on NCTC 120. The result obtained with DD3008 demonstrated that the capsular polysaccharide was not the φE125 receptor (Table 2). We next performed an immunoblot on whole-cell lysates of the NCTC and ATCC strains with a commercially available monoclonal antibody (3D11) that reacts with B. mallei LPS O antigen (Fig. 2A). All of the NCTC and ATCC B. mallei strains, with the exception of NCTC 120, demonstrated a typical ladder LPS appearance after immunostaining with 3D11 (Fig. 2A). The laboratory-passaged derivative of ATCC 15310, termed DB110795, also does not form plaques with φE125 (Table 2). We performed an immunoblot on a whole cell lysate of DB110795 with the monoclonal antibody 3D11 and found that it did not produce LPS O antigen (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that there is a correlation between the absence of LPS O antigen and resistance to plaque formation by φE125.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of B. mallei LPS O antigens. Bacteria were washed, resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled, treated with proteinase K, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The LPS O antigens were blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and reacted with the monoclonal antibody 3D11. (A) LPS O-antigen profiles of NCTC and ATCC B. mallei strains. (B) Comparative LPS O-antigen profiles of φE125-resistant and φE125-susceptible B. mallei strains. All strains form plaques with bacteriophage φE125 except NCTC 120, DB110795, and NCTC 120 (pBHR1).

A previous study demonstrated that IS407A is active in B. mallei during serial subculture in vitro. IS407A integrated into the capsule gene cluster in B. mallei DD420 and resulted in a capsule-deficient strain (24). The LPS O-antigen gene clusters of NCTC 120 and DB110795 were analyzed to determine if this 1.2-kb insertion element (IS) was responsible for the lack of LPS O-antigen production by these strains. The nucleotide sequence of the B. pseudomallei LPS O-antigen gene cluster is known (23), and it was used to design eight PCR primer pairs that would result in 2-kb amplicons spanning the LPS O-antigen locus in B. mallei. Eight 2-kb amplicons were generated when PCR assays were performed with these primer pairs and genomic DNA from B. pseudomallei 1026b and B. mallei ATCC 23344 (data not shown). When the PCR assays were performed with genomic DNA from NCTC 120 and DB110795, seven 2-kb amplicons and one 3.2-kb amplicon were produced (data not shown). The 3.2-kb amplicons generated using primer pairs 7-1-7-2 (NCTC 120) and 8-1A-8-2A (DB110795) were cloned and sequenced. The sequencing results demonstrate that NCTC 120 and DB110795 harbor IS407A insertions in wbiE and wbiG, respectively. There was a 4-bp duplication of the sequence 5′-CTGC-3′ flanking the insertion site in NCTC 120 and a 4-bp duplication of the sequence 5′-GCAG-3′ flanking the insertion site in DB110795. Interestingly, the B. mallei capsule mutant DD420 harbors an IS407A insertion in wcbF that is also flanked by a duplication of the sequence 5′-GCAG-3′ (24).

The wbiE::IS407A mutation in NCTC 120 was complemented by providing the wbiE gene from ATCC 23344 in trans on the broad-host-range plasmid pBHR1 (Table 1). Figure 2B shows that NCTC 120 (pBHR1) does not produce LPS O antigen but that NCTC 120 (pBHR1-wbiE) does. Furthermore, NCTC 120 (pBHR1-wbiE) formed plaques with φE125, but NCTC 120 (pBHR1) did not. These results demonstrate that the lack of LPS O-antigen production by NCTC 120 is due to an IS407A mutation in wbiE and that the LPS O antigen is required for plaque formation by φE125.

BML10 is immune to φE125 superinfection and produces LPS O antigen.

Lysogenic bacteria are resistant to superinfection by the temperate bacteriophage that they harbor. Following infection, the φE125 genome integrates in the B. mallei chromosome at a specific site and becomes a prophage (see below). ATCC 23344 was infected with φE125, and a lysogenic derivative was isolated and designated BML10. B. mallei BML10 spontaneously produced approximately 500 φE125 per ml of broth culture. In comparison, B. thailandensis E125 spontaneously produced approximately 1,100 φE125 per ml of broth culture. As shown in Table 2, φE125 does not form plaques on BML10. Whole-cell lysates of ATCC 23344 and BML10 were analyzed by immunoblot analysis with the monoclonal antibody 3D11, and both strains produced a typical LPS O-antigen banding pattern (Fig. 2B). As shown above, NCTC 120 and DB110795 are resistant to infection with φE125 because they do not produce LPS O antigen. BML10, on the other hand, produces LPS O antigen but is still resistant (immune) to φE125 superinfection, probably via a prophage-encoded gene product(s). It should be noted that B. thailandensis E125 also harbors the φE125 prophage and is also immune to superinfection with φE125 (Table 2).

Molecular characterization of the bacteriophage φE125 genome.

The φE125 genome was digested with HindIII, and eight fragments were generated of the following sizes: 1.0, 3.2, 4.4, 5.5, 7.3, 9.0, 9.9, and 13.0 kb. The fragments were heated to 80°C, and the 9.0-kb fragment dissociated into two fragments (1.7 and 7.3 kb), suggesting the presence of a cohesive (cos) site on this fragment (data not shown). The eight HindIII fragments were cloned, and their nucleotide sequences were determined. The nucleotide-sequencing results are depicted schematically in Fig. 3, and pertinent features of φE125 genes and gene products are shown in Table 3.

FIG. 3.

Physical and genetic map of the bacteriophage φE125 genome. The locations and directions of transcription of genes are represented by arrows, and the gene names are shown below. The locations of HindIII endonuclease restriction sites are shown (H), and the insertion sequence ISBt3 is represented as a rectangle. The locations of the cohesive (cos) and bacteriophage attachment (attP) sites are shown above and below the φE125 genome, respectively. The putative functions of proteins encoded by φE125 genes are color coded.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of bacteriophage φE125 genes and gene products

| Gene | Orientationa | Start (position) | End (position) | Size of protein (kDa) | Protein function and homologs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R | 46 | 531 | 17.2 | Terminase (small subunit); phage GMSE-1 Orf16; 1e-12; AF311659; phage 7201 Orf21; 2e-09; AF145054 |

| 2 | R | 541 | 2253 | 64.2 | Terminase (large subunit); E. coli YmfN; 1e-162; NP_415667; phage D3 terminase; 1e-125; NP_061498 |

| 3 | R | 2250 | 2435 | 6.3 | |

| 4 | R | 2440 | 3699 | 46.4 | Portal protein; H. influenzae Orf25-like protein; 1e-40; AAF27362; CP-933C Z1849; 1e-40; NP_287334 |

| 5 | R | 3759 | 4664 | 31.7 | Capsid assembly protein/protease; phage WO Orf7; 8e-44; AB036665; prophage Gifsy-1 STM2605; 2e-34; AE008818 |

| 6 | R | 4767 | 6074 | 46.3 | Major capsid protein; CP-933N Z1804; 2e-09; NP_287292; CP-933M Z1360; 2e-09; NP_286882 |

| 7 | R | 6134 | 6319 | 6.4 | |

| 8 | R | 6326 | 6892 | 20.6 | |

| 9 | R | 6892 | 7218 | 12.1 | Phage HK022 gp9; 3e-08; AF069308 |

| 10 | R | 7211 | 7633 | 15.4 | Phage HK97 gp10; 4e-20; AF069529 |

| CP-933M Z1368; 1e-19; NP_286890 | |||||

| 11 | R | 7630 | 7977 | 12.1 | |

| 12 | R | 8039 | 8497 | 16.4 | Major tail subunit protein; phage HK97 gp12; 2e-20; NP_037706; E. coli ECs1800; 7e-17; NP_309827 |

| 13 | R | 8519 | 8989 | 17.4 | Tail assembly chaperone protein; phage HK97 gp13; 9e-06; NP_037708; phage HK97 gp14; 1e-05; NP_037707 |

| 14 | R | 8989 | 9273 | 10.0 | Phage HK97 gp14; 9e-07; NP_037707 |

| 15 | R | 9287 | 13351 | 143.0 | Tail length tape measure protein; CP-933P Z6034; 2e-25; NP_287971; E. coli ECs2240; 2e-25; NP_310267 |

| 16 | R | 13348 | 13686 | 12.5 | Minor tail protein; phage HK97 gp17; 1e-18; NP_037711; phage HK022 gp17; 3e-18; NP_037677 |

| 17 | R | 13695 | 15083 | 50.1 | |

| 18 | R | 15080 | 15763 | 25.2 | Minor tail protein; P. aeruginosa PA0638; 2e-62; G83565; phage N15 gp18; 3e-51; AF064539 |

| 19 | R | 15783 | 16565 | 28.6 | Tail component protein; P. aeruginosa PA0639; 1e-51; AE004499; phage HK97 gp19; 1e-43; AF069529 |

| 20 | R | 16562 | 17146 | 20.1 | Tail component protein; Y. pestis YPO2129; 3e-33; AJ414151; phage N15 gp20; 3e-28; AF064539 |

| 21 | R | 17143 | 20448 | 118.3 | Tail tip fiber protein; Y. pestis YPO2131; < 1e-119; AJ414151; phage N15 gp21; < 1e-119; AF064539 |

| 22 | R | 20445 | 20759 | 11.6 | |

| 23 | R | 20759 | 21493 | 27.6 | |

| 24 | R | 21536 | 21748 | 7.6 | Class II holin; phage PS119 gp13; 8e-04; AJ011581; phage PS34 gp13; 8e-04; AJ011580 |

| 25 | R | 21826 | 22230 | 14.7 | Lysozyme; X. fastidiosa XF0513; 2e-13; AE003900; phage PS119 gp19; 2e-11; AJ011581 |

| 26 | R | 22227 | 22775 | 18.6 | |

| 27 | R | 22918 | 23706 | 30.2 | DNA adenine methylase; phage GMSE-1 Orf10; 1e-40; AF311653; A. lwoffii AlwI methylase; 5e-19; AF431889 |

| 28 | R | 23815 | 24693 | 30.9 | |

| 29 | R | 24875 | 25435 | 19.1 | P. aeruginosa PA1508; 7e-07; AE004579; Y. pestis YPO0866; 8e-07; AE004579 |

| 30 | R | 25432 | 26166 | 26.3 | P. aeruginosa PA0822; 5e-23; AE004517; P. aeruginosa PA0823; 4e-09; AE004517 |

| 31 | R | 26194 | 27285 | 39.4 | P. aeruginosa PA0821; 1e-48; AE004517 |

| 32 | L | 28059 | 27418 | 25.0 | |

| 33 | R | 28145 | 28816 | 25.3 | Plasmid pFKN Orf11; 2e-17; AF359557; plasmid pNL1 Orf520; 3e-04; AF079317 |

| 29062 | 29014 | attP (3′ end of tRNA ProUGG) | |||

| 34 | L | 30292 | 29192 | 42.2 | Site-specific integrase; prophage XfP2 XF2530; 6e-09; AE004060; CP-933M Z1323; 1e-08; NP_286846 |

| 35 | L | 30609 | 30292 | 11.8 | |

| 36 | L | 31142 | 30642 | 19.3 | |

| 37 | L | 32131 | 31139 | 37.2 | M. tuberculosis Rv2734; 8e-32; NP_217250; N. punctiforme hypothetical protein; 4e-28; AAK68643 |

| 38 | L | 33180 | 32128 | 37.9 | |

| 39′ | L | 33314 | 33195 | ||

| tnpB | L | 34204 | 33350 | 32.6 | Transposase (IS3 family); IS868 ORF4; 1e-101; X55075; IS401 transposase subunit; 4e-99; L09108 |

| tnpA | L | 34539 | 34261 | 10.7 | Transposase (IS3 family); IS401 transposase subunit; 6e-29; L09108; IS868 Orf1; 9e-20; X55075 |

| ′39 | L | 34794 | 34636 | ||

| Gene | Orientationa | Start (position) | End (position) | Size of protein (kDa) | Protein function and homologs |

| 40 | L | 35195 | 34794 | 14.6 | Phage M×8 p77; 0.1; AF396866 |

| 41 | L | 35863 | 35192 | 25.1 | CP-9330 Z2097; 4e-05; AE005346; CP-933U Z3120; 2e-04; AE005422 |

| 42 | L | 36671 | 35877 | 29.8 | |

| 43 | L | 37670 | 36858 | 29.7 | Y. pestis YPMT1.49c; 1e-38; NC_003134; S. enterica HCM2.0006c; 2e-38; AL513384 |

| 44 | L | 37816 | 37667 | 5.5 | |

| 45 | R | 38065 | 38718 | 28.6 | |

| 46 | R | 38919 | 39173 | 9.1 | |

| 47 | L | 39586 | 39170 | 15.5 | |

| 48 | L | 39993 | 39862 | 4.7 | |

| 49 | L | 40278 | 40003 | 10.4 | |

| 50 | R | 40519 | 40662 | 5.0 | |

| 51 | R | 40747 | 40935 | 7.0 | |

| 52 | L | 41555 | 41163 | 14.4 | Repressor protein; X. fastidiosa XF0499; 9e-14; AE003899; prophage e14 protein b1145; 9e-04; F64859 |

| 53 | R | 42006 | 42338 | 11.8 | |

| 54 | L | 42821 | 42567 | 9.4 | |

| 55 | R | 43007 | 43447 | 15.8 | Phage phi CTX Orf33; 0.24; BAA36261 |

| 56 | R | 43452 | 44588 | 42.1 | DNA cytosine methylase; C. freundii Cfr9I methylase; 8e-45; X17022; P. alcaligenes Pac25I methylase; 1e-44; U88088 |

| 57 | R | 44585 | 45583 | 36.8 | PAPS reductase/sulfotransferase; phage 186 Orf84; 6e-55; U32222; A. pernix APE2075; 8e-07; F72512 |

| 58 | R | 45618 | 46439 | 29.9 | DNA partitioning protein; R. equi ParA; 1e-06; NP_066815; L. lactis ParA; 2e-05; NP_266252 |

| 59 | R | 46436 | 46696 | 9.5 | |

| 60 | R | 46850 | 47842 | 36.3 | CP-933R Z2397; 7e-06; NP_287824 |

| 61 | R | 48035 | 48388 | 13.9 | Prophage pi3 protein 45; 4e-05; AL596172; L. monocytogenes lmo2306; 6e-05; CAD00384 |

| 62 | R | 48385 | 48741 | 13.2 | |

| 63 | R | 48843 | 49181 | 12.6 | |

| 64 | R | 49172 | 49516 | 13.1 | |

| 65 | R | 49492 | 49752 | 9.8 | |

| 66 | R | 49761 | 50408 | 24.1 | |

| 67 | R | 50482 | 51876 | 51.3 | S. meliloti SMa0594; 6e-11; NP_435557 |

| 68 | L | 52603 | 52217 | 14.1 | Helix-turn-helix transcriptional regulator; S. meliloti SMc00089; 4e-10; NP_385047; A. tumefaciens AGR_C_1081p; 2e-04; NP_353634 |

| 69 | L | 52857 | 52600 | 9.3 | P. horikoshii PHS013; 1e-04; NP_142388; P. jensenii Orf10; 0.006; CAC38044 |

| 70 | R | 52916 | 53272 | 13.1 | Class I holin; X. nematophila prophage Orf7; 1e-16; CAB58450; H. influenzae holin-like protein; 4e-08; AF198256 |

R, right; L, left.

The φE125 genome is a linear molecule of 53,373 bp in length, and it contains 10-base 3′ single-stranded extensions on the left (3′-GCGGGCGAAG-5′) and right (5′-CGCCCGCTTC-3′), as depicted in Fig. 3. The G + C content of the φE125 genome is 61.2%, which is lower than the 69.3% G + C content of the B. thailandensis genome (77). The φE125 genome encodes 70 proteins, and 44% of them show no homology to proteins in the GenBank databases using the BLASTP search algorithm (Table 3 and Fig. 3). The bacteriophage genome also harbors a novel IS3 family insertion sequence (45), designated ISBt3 (Table 3 and Fig. 3). ISBt3 is 1,318 bp in length, and it has 27-bp terminal inverted repeats flanked by a 3-bp direct duplication. ISBt3 integrated into φE125 gene39, suggesting that the encoded protein (gp39) is not essential for a productive lysogenic infection.

Twenty-eight proteins encoded by φE125 are similar to proteins encoded by other bacteriophage, prophage, or prophage-like elements (Table 3). Interestingly, there are numerous similarities to HK022 and HK97 (34) and to λ-like cryptic prophages in E. coli O157 Sakai (52) and E. coli O157 EDL933 (53). Bacteriophage genomes are composed of a mosaic of multigene modules, each of which encodes a group of proteins involved in a common function, such as DNA packaging, head biosynthesis, tail biosynthesis, host lysis, lysogeny, or replication (11, 28, 34, 37). The φE125 genome contains a unique combination of multigene modules involved in DNA packaging, head morphogenesis, tail morphogenesis, and host lysis (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The relative order of these modules in the φE125 genome is similar to that of other Siphoviridae genomes (11, 34, 37, 42). Since φE125 possesses both structural and genetic similarities to the λ supergroup group of Siphoviridae, it probably should be included with λ, N15, HK97, HK022, and D3 in the λ-like genus (11).

Early bacteriophage gene functions (lysogeny and replication) are typically located on the right half of Siphoviriae genomes, as depicted in Fig. 3 (11). However, the putative lysogeny and replication modules of φE125 appear to be unique relative to other members of the Siphoviridae. Some of the unusual proteins encoded by the right half of the φE125 genome include a DNA adenine methylase (gp27), a DNA cytosine methylase (gp56), a 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) reductase or PAPS sulfotransferase (gp57), and a chromosome partitioning protein (gp58) (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The φE125 genome also contains two putative holins, gp70 (class I) and gp24 (class II), to coordinate the programmed release of lysozyme (gp25) from the cytoplasm prior to bacteriophage release (72). It is currently unknown if gp70, gp24, or both gp70 and gp24 are required for membrane permeabilization during the φE125 life cycle. Finally, several recently sequenced bacterial genomes also encode proteins with similarities to gp29, gp30, gp31, gp33, gp37, gp43, gp61, gp67, gp68, and gp69 (Table 3), suggesting the presence of prophages or prophage remnants in these bacterial genomes. Alternatively, φE125 may have acquired these genes via horizontal transfer from a bacterial host, and they may provide a selective advantage to a lysogen harboring this bacteriophage.

φE125 integrates into a proline tRNA (UGG) gene in B. thailandensis and B. mallei.

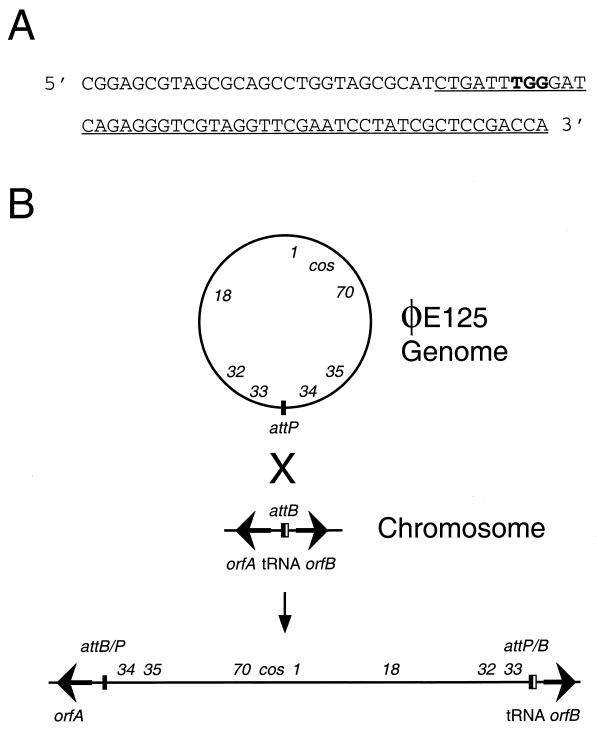

As with other lambdoid bacteriophages, φE125 DNA probably circularizes at the cos sites after it is injected into the bacterial cell and follows one of two possible pathways (14). The circularized genome may replicate and produce bacteriophage progeny (lytic response), or it may integrate into the bacterial chromosome and be maintained in a quiescent state (lysogenic response). Temperate bacteriophage genomes often contain an attachment site (attP) that they utilize to integrate into a homologous region on the bacterial genome (attB) via site-specific recombination (18). Since φE125 encodes a site-specific integrase (gp34), we were interested in identifying where the φE125 genome was integrated in B. thailandensis E125 and B. mallei BML10 and in determining the nucleotide sequences of attP and attB.

Chromosomal DNA flanking one side of the φE125 attachment site in B. thailandensis E125 was cloned and sequenced (see Materials and Methods). The nucleotide sequence of this region contained a 49-bp sequence that was identical for the φE125 genome and the B. thailandensis E125 chromosome. This sequence corresponded to the 3′ end of a 77-bp proline tRNA (UGG) gene on the B. thailandensis chromosome (Fig. 4A). tRNA genes often serve as target sequences for site-specific integration of temperate bacteriophages, plasmids, and pathogenicity islands (27, 63). Immediately upstream of the proline tRNA (UGG) gene on the B. thailandensis chromosome was a divergently transcribed gene designated orfB (Fig. 4B). BLASTP results demonstrated that OrfB was 52% identical to RSc1539, a probable hydrolase protein from R. solanacearum. The B. thailandensis proline tRNA (UGG) gene and orfB were also present in the B. mallei ATCC 23344 genome (http://www.tigr.org/), and they were 100 and 91% identical at the nucleotide level, respectively. Downstream of the proline tRNA (UGG) gene in B. mallei ATCC 23344 was orfA, a gene that encoded a protein with 40% identity to RSc2888, a hypothetical protein from R. solanacearum (Fig. 4B). In order to determine if φE125 integrates in the 3′ end of the tRNA proline (UGG) gene in B. mallei, we designed PCR primers specific for B. mallei orfA and φE125 gene34 (Fig. 4B). B. mallei ATCC 23344 and φE125 DNA did not yield a PCR product with these primers, but B. mallei BML10 did (data not shown). These results, represented schematically in Fig. 4B, demonstrate that bacteriophage φE125 integrates into the 3′ end of the proline tRNA (UGG) gene in B. mallei and B. thailandensis. It should also be noted that attachment at this site leaves the proline tRNA (UGG) gene intact on the right side, as depicted in Fig. 4B.

FIG. 4.

Bacteriophage φE125 integrates into the proline tRNA (UGG) gene in B. mallei and B. thailandensis. (A) The nucleotide sequence of the proline tRNA (UGG) gene of B. mallei ATCC 23344 and B. thailandensis E125. The underlined sequence represents the 49-bp attachment site that is identical in the φE125 genome (attP), the B. mallei chromosome (attB), and the B. thailandensis chromosome (attB). The location of the anticodon in the proline tRNA gene is shown in bold. (B) Schematic representation of integration of the φE125 genome into the proline tRNA (UGG) gene of B. mallei and B. thailandensis. The φE125 genome is depicted as a circle, and the approximate locations of gene1, gene18, gene32, gene33, gene34, gene35, gene70, and the cos site are shown. The B. mallei and B. thailandensis chromosomes are represented as a line, and the location and direction of transcription of orfA and orfB are represented by arrows. The 5′ end of the proline tRNA (UGG) gene is shown as a thin white rectangle, and the 3′ end (the attachment site) is shown as a thin black rectangle. Following site-specific recombination (X), the orfA and orfB genes are separated by the integrated φE125 prophage.

Survey of B. thailandensis strains for the presence of φE125-like prophages.

As mentioned above, lysogenic bacteria are immune to superinfection with the same (or similar) bacteriophage that they harbor. The results presented in Table 2 demonstrate that all thirty-two B. thailandensis strains in our collection, including E125, are resistant to infection with φE125. To determine if the strains were resistant to infection because they harbored φE125-like prophages, genomic DNA was isolated from all strains and PCR was performed with primer pairs specific for four distinct regions of the φE125 genome. The primer pairs used were 9.5R and 3.2R (gene9 and gene10), 7.5F and 5.5F (gene21), 18R and 11F (gene42), and 4.4R and 9.5F (gene67). Only ten of the thirty-two B. thailandensis strains yielded positive PCR results with these primer pairs (E96, E100, E125, E253, E254, E256, E263, E264, E286, and E293). As expected, E125 was positive for all of the PCR primer pairs. The only other strain that was positive for all four primer pairs was E286. Strains E253 and E264 yielded positive PCR results for two primer pairs, and all of the other strains were positive for three primer pairs. All 10 B. thailandensis strains spontaneously produced bacteriophage that formed plaques on B. mallei ATCC 23344. Thus, it appears that E96, E100, E253, E254, E256, E263, E264, E286, and E293 all harbor φE125-like prophage and may be immune to superinfection with φE125. On the other hand, 22 B. thailandensis strains did not yield a positive PCR product with any of the primer pairs and probably do not harbor a φE125-like prophage. These observations suggest that the molecular mechanism of φE125 resistance in these strains is probably not due to superinfection immunity.

Functional analysis of the putative DNA methyltransferases of φE125.

φE125 encodes two proteins, gp27 and gp56, that contain similarities to Type II DNA methyltransferases (Table 3). Site-specific DNA methylation usually leads to the formation of three different products: N6-methyladenine (m6A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), and N4-methylcytosine (m4C). Some tailed bacteriophage genomes contain unusual or modified DNA bases that may be important in protecting the infecting bacteriophage DNA from host restriction endonucleases (1). gp27 is a putative DNA adenine methylase, and gp56 is a putative DNA cytosine methylase. We were interested in determining if gp27 and gp56 were functional DNA methyltransferases.

The plasmids pCR2.1, pAM1, and pCM1 (Table 1) were transformed into E. coli DB24, a strain that is deficient in all of the E. coli DNA methylases (36), and DNA methylase dot blot assays were performed with rabbit primary antibodies specific for m6A and m4C. Figure 5A shows that the m6A antibody reacted with genomic DNA samples from λ (positive control) and DB24 (pAM1) but did not react with DB24 (pCR2.1) or DB24 (pCM1). The m6A antibody also reacted with genomic DNA samples from B. mallei BML10 and bacteriophage φE125 (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, there was only background reactivity of the m6A antibody with genomic DNA from B. thailandensis E125 and B. mallei ATCC 23344 (Fig. 5A). It appears that the φE125 m6A methylase has little or no activity in the B. thailandensis lysogen but is very active in the B. mallei lysogen (Fig. 5A, compare E125 and BML10). It is currently unclear if the B. mallei BML10 genome contains m6A or if the positive signal obtained with the m6A antibody is due to the φE125 genome, which also contains m6A (Fig. 5A). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that gene27 is expressed in DB24, that gp27 is a functional m6A methylase, and that the φE125 genome contains m6A.

FIG. 5.

Dot blot assay to detect genomic DNA methylation using rabbit primary antibodies specific for m6A or m4C. (A) Methylase dot blot assay using polyclonal antibodies specific for m6A. Bacteriophage 2 genomic DNA was used as a positive (+) control. (B) Methylase dot blot assay using polyclonal antibodies specific for m4C. E. coli DB24 genomic DNA methylated by M.RsaI served as a positive (+) control. The quantities of genomic DNAs spotted on each panel are shown.

The m4C antibody did not react with genomic DNA from DB24 (pCR2.1), DB24 (pAM1), DB24 (pCM1), or B. thailandensis E125, but it did react with DB24 genomic DNA methylated with M.RsaI as a positive control (Fig. 5B). This indicates that gene56 is not expressed or is inactive in DB24 (pCM1) and B. thailandensis E125. On the other hand, positive signals were obtained when the m4C antibody was reacted with genomic DNA from B. mallei BML10 and φE125 (Fig. 5B). It is likely that gp56 is an m4C methylase because genomic DNA from B. mallei BML10 reacts with the m4C antibody, but B. mallei ATCC 23344 genomic DNA does not (Fig. 5B). Alternatively, φE125 infection may activate a cryptic B. mallei m4C methylase or a φE125 protein other than gp56 may be responsible for the m4C methylase activity in B. mallei BML10. It is not clear if the B. mallei BML10 genome contains m4C or if the positive signal obtained with the m4C antibody is strictly due to m4C methylation of the φE125 genome (Fig. 5B). Further studies will be required to determine the DNA specificities of gp27 and gp56.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated and characterized φE125, a tailed bacteriophage specific for B. mallei. The host range of φE125 was examined by using bacteria from three genera of β-Proteobacteria (Burkholderia, Pandoraea, and Ralstonia) and five genera of γ-Proteobacteria (Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Salmonella, Serratia, and Escherichia). In fact, eighteen different Burkholderia species were tested, and only B. mallei strains were sensitive to φE125 (Table 2). The most-impressive host specificity results were obtained with B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis, two species closely related to B. mallei. Bacteriophage φE125 did not form plaques on any of the 50 strains of B. pseudomallei or 32 strains of B. thailandensis tested in this study. Glanders was eradicated from North America in the 1930s and we were able to test only 13 strains of B. mallei due to the difficulty of obtaining unique isolates of this species. Nonetheless, the results clearly demonstrate that φE125 specifically forms plaques on B. mallei, and we hope to use it, in conjunction with other methods, as a diagnostic tool for B. mallei.

The LPS O antigen was required for infection with φE125, suggesting that this molecule is the bacteriophage receptor. This is similar to the λ-like bacteriophage D3, which utilizes the LPS O antigen of P. aeruginosa for infection (37, 38). It is surprising that φE125 did not infect B. pseudomallei or B. thailandensis because the chemical structure of the B. mallei LPS O antigen, a heteropolymer of repeating d-glucose and l-talose, is similar to that previously described for these closely related species (10, 12, 35, 54). In fact, the gene clusters encoding the B. mallei and B. pseudomallei LPS O antigens are 99% identical at the nucleotide level (12, 23). However, unlike B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis, the B. mallei LPS O antigen is devoid of an O-acetyl group at the 4′ position of the l-talose residue. The chemical structure of the B. mallei LPS O antigen is as follows: (3)-β-d-glucopyranose-(1,3)-6-deoxy-α-l-talopyranose-(1-, in which the talose residue contains 2-O-methyl or 2-O-acetyl substituents (12). Our present hypothesis is that B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis are resistant to infection with φE125 because the O-acetyl group at the 4′ position of the l-talose residue alters the conformation of the LPS O antigen and/or blocks the bacteriophage binding site. B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis possess an O-acetyltransferase that is responsible for transferring the O-acetyl group to the 4′ position of the l-talose residue. This O-acetyltransferase gene is not present, is not expressed, or is mutated in B. mallei. We are currently attempting to identify the B. pseudomallei O-acetyltransferase gene and provide it in trans to B. mallei to see if it O-acetylates the 4′ position of l-talose and confers resistance to φE125. Alternatively, inactivation of the O-acetyltransferase gene should make B. pseudomallei sensitive to φE125.

It is also possible that B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis are immune to superinfection with φE125 because they harbor a φE125-like prophage. The nucleotide sequence of a 1,068-bp HindIII fragment from a B. mallei-specific bacteriophage produced by B. pseudomallei 1026b (φ1026b) was recently obtained and was found to be 98% identical to the 1,068-bp HindIII fragment from φE125 (D. DeShazer, unpublished data). However, the nucleotide sequences of other HindIII fragments from φ1026b displayed no similarities to φE125, indicating that φ1026b and φE125 are distinct bacteriophages that share regions (modules) of genetic similarity. We found that 10 of the 32 B. thailandensis strains in our collection harbor a φE125-like prophage, and the genomic sequence of B. pseudomallei K96243 also contains several genes that are nearly identical to φE125 genes (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/). Thus, it is clear that some B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis strains are lysogenic for a φE125-like bacteriophage and may be immune to superinfection with φE125. It is also important to note that 22 B. thailandensis strains in our collection did not possess an φE125-like prophage, suggesting that superinfection immunity alone is not responsible for their resistance to infection with φE125.

In this study, we found that B. mallei NCTC 120 and B. mallei DB110795 do not produce LPS O antigens due to IS407A insertions in wbiE and wbiG, respectively. Burtnick et al. (12) have recently obtained identical results with B. mallei NCTC 120 and B. mallei ATCC 15310, the parental strain of B. mallei DB110795. We found that B. mallei ATCC 15310 does produce LPS O antigen (Fig. 2A) and does not contain the wbiG::IS407A mutation. In fact, the ATCC stock cultures (1964 and 1974) of B. mallei ATCC 15310 do not harbor IS407A insertions in wbiG (Jason Bannan, personal communication). B. mallei DB110795 was obtained by routine laboratory passage of B. mallei ATCC 15310 at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). The strain used in the study of Burtnick et al. (12) was obtained from USAMRIID and was probably B. mallei DB110795, not B. mallei ATCC 15310. It was previously reported by members of our group that IS407A integrated into a capsular polysaccharide gene during repeated laboratory passage of B. mallei ATCC 23344 (24). Taken together, these results suggest that IS407A transposition may be relatively common during routine laboratory passage of this microorganism. Serial subculture of B. mallei on laboratory media results in a loss of virulence for animals (48, 49, 51, 57), and it is tempting to speculate that IS407A transposition is responsible, directly or indirectly, for this phenomenon.

Finally, we found that φE125 genomic DNA contained the methylated bases m6A and m4C (Fig. 5). DNA methylation may protect φE125 DNA from host restriction endonucleases (1), or it may be involved in some other aspect of the φE125 life cycle. We cloned and expressed φE125 gene27 in E. coli and found that gp27 was a functional m6A methylase. We were unable to provide direct evidence that gp56 was a m4C methylase, but it was intriguing that φE125 DNA and genomic DNA from a B. mallei lysogen contained m4C. It was surprising that genomic DNA from a B. mallei lysogen contained m6A and m4C, but genomic DNA from a B. thailandensis lysogen did not. We are currently examining the possibility that gp27 and gp56 require host factors for production and/or activity that are present in B. mallei but not in B. thailandensis. Type II DNA methylases specifically bind and methylate recognition sequences on a DNA substrate (58). The DNA sequence specificities of gp27 and gp56 are currently unknown, but BLASTP results show that gp56 is similar to cytosine methylases that recognize and methylate the sequence 5′-CCCGGG-3′, which occurs nine times in the φE125 genome. φE125 DNA was treated with five restriction endonucleases that recognize this sequence (SmaI, XmaI, Cfr9I, PspAI, and XmaCI), and they all cleaved the DNA into nine fragments of the predicted sizes (D. DeShazer and J. A. Jeddeloh, unpublished data). The fact that cleavage was not blocked strongly suggests that this site is not methylated. Further studies are required to determine the specificity of gp27 and gp56 and to understand their role(s) in the φE125 life cycle.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bart Currie, Pamela A. Sokol, Norman W. Schaad, Joseph O. Falkinham III, Rich Roberts, Christine Segonds, Christian O. Brämer, Rick Titball, Hui Zhang, Ron R. Read, and Eiko Yabuuchi for providing bacterial strains and reagents. We also thank Kathy Kuehl for electron microscopy assistance and Tim Hoover and Rick Ulrich for critically reading the manuscript. We are indebted to Jason Bannan (ATCC) for confirming that the 1964 and 1974 B. mallei ATCC 15310 stock cultures did not contain IS407A insertions in the wbiG gene.

This work was supported in part by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant to D.E.W. D.E.W. is a Canada Research Chair in Microbiology and performed this work at USAMRIID while on sabbatical leave from the University of Calgary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, H.-W. 1999. Tailed bacteriophages: the order Caudovirales. Adv. Virus Res. 51:135-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackermann, H.-W. 2001. Frequency of morphological phage descriptions in the year 2000. Arch. Virol. 146:843-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alibek, K., and S. Handelman. 1999. Biohazard: the chilling true story of the largest covert biological weapons program in the world. Random House, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anuntagool, N., P. Aramsri, T. Panichakul, V. Wuthiekanun, R. Kinoshita, N. J. White, and S. Sirisinha. 2000. Antigenic heterogeneity of lipopolysaccharide among Burkholderia pseudomallei clinical isolates. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 31:146-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauernfeind, A., C. Roller, D. Meyer, R. Jungwirth, and I. Schneider. 1998. Molecular procedure for rapid detection of Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2737-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brämer, C. O., P. Vandamme, L. F. da Silva, J. G. C. Gomez, and A. Steinbüchel. 2001. Burkholderia sacchari sp. nov., a polyhydroxyalkanoate-accumulating bacterium isolated from soil of a sugar-cane plantation in Brazil. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. E vol. Microbiol. 51:1709-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brett, P. J., D. DeShazer, and D. E. Woods. 1997. Characterization of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei-like strains. Epidemiol. Infect. 118:137-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brett, P. J., D. DeShazer, and D. E. Woods. 1998. Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., description of a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:317-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brussow, H., and F. Desiere. 2001. Comparative phage genomics and the evolution of Siphoviridae: insights from dairy phages. Mol. Microbiol. 39:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burtnick, M. N., P. J. Brett, and D. E. Woods. 2002. Molecular and physical characterization of Burkholderia mallei O antigens. J. Bacteriol. 184:849-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cain, C. C., A. T. Henry, R. H. Waldo III, L. J. Casida, Jr., and J. O. Falkinham III. 2000. Identification and characteristics of a novel Burkholderia strain with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4139-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell, A. 1994. Comparative molecular biology of lambdoid phages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:193-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casadaban, M. J. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104:541-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Biological and chemical terrorism: strategic plan for preparedness and response. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49(RR-4):1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coenye, T., E. Falsen, B. Hoste, M. Ohlen, J. Goris, J. R. W. Govan, M. Gillis, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Description of Pandoraea gen. nov. with Pandoraea apista sp. nov., Pandoraea pulmonicola sp. nov., Pandoraea pnomenusa sp. nov., Pandoraea sputorum sp. nov. and Pandoraea norimbergensis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:887-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig, N. L. 1988. The mechanism of conservative site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22:77-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cravitz, L., and W. R. Miller. 1950. Immunologic studies with Malleomyces mallei and Malleomyces pseudomallei. I. Serological relationships between M. mallei and M. pseudomallei. J. Infect. Dis. 86:46-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Currie, B. J., D. A. Fisher, D. M. Howard, J. N. Burrow, D. Lo, S. Selva-Nayagam, N. M. Anstey, S. E. Huffam, P. L. Snelling, P. J. Marks, D. P. Stephens, G. D. Lum, S. P. Jacups, and V. L. Krause. 2000. Endemic melioidosis in tropical northern Australia: a 10-year prospective study and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:981-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dance, D. A. B. 1996. Melioidosis, p. 925-930. In G. C. Cook (ed.), Manson's tropical diseases. W. B. Saunders Company Ltd, London, United Kingdom.

- 22.DeShazer, D., P. J. Brett, R. Carlyon, and D. E. Woods. 1997. Mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei with Tn5-OT182: isolation of motility mutants and molecular characterization of the flagellin structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 179:2116-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeShazer, D., P. J. Brett, and D. E. Woods. 1998. The type II O-antigenic polysaccharide moiety of Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharide is required for serum resistance and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1081-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeShazer, D., D. M. Waag, D. L. Fritz, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Identification of a Burkholderia mallei polysaccharide gene cluster by subtractive hybridization and demonstration that the encoded capsule is an essential virulence determinant. Microb. Pathog. 30:253-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelstein, R. A., P. Atthasampunna, and M. Chulasamaya. 2000. Pseudomonas (Burkholderia) pseudomallei in Thailand 1964-1967; geographic distribution of the organism, attempts to identify cases of active infection, and presence of antibody in representative sera. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:232-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godfrey, A. J., S. Wong, D. A. Dance, W. Chaowagul, and L. E. Bryan. 1991. Pseudomonas pseudomallei resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics due to alterations in the chromosomally encoded beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1635-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker, J., G. Blum-Oehler, I. Muldorfer, and H. Tschape. 1997. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1089-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. M. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. D. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holloway, B. W., U. Romling, and B. Tummler. 1994. Genomic mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology 140:2907-2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howe, C., and W. R. Miller. 1947. Human glanders: report of six cases. Ann. Intern. Med. 26:93-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howe, C. 1950. Glanders, p. 185-202. In H. A. Christian, (ed.), The Oxford medicine. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 33.Jennings, W. E. 1963. Glanders, p. 264-292. In T. G. Hull (ed.), Diseases transmitted from animals to man. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

- 34.Juhala, R. J., M. E. Ford, R. L. Duda, A. Youlton, G. F. Hatfull, and R. W. Hendrix. 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J. Mol. Biol. 299:27-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knirel, Y. A., N. A. Paramonov, A. S. Shashkov, N. K. Kochetkov, R. G. Yarullin, S. M. Farber, and V. I. Efremenko. 1992. Structure of the polysaccharide chains of Pseudomonas pseudomallei lipopolysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 233:185-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong, H., L.-F. Lin, N. Porter, S. Stickel, D. Byrd, J. Posfai, and R. J. Roberts. 2000. Functional analysis of putative restriction-modification system genes in the Helicobacter pylori J99 genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3216-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kropinski, A. M. 2000. Sequence of the genome of the temperate, serotype-converting, Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage D3. J. Bacteriol. 182:6066-6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuzio, J., and A. M. Kropinski. 1983. O-antigen conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 by bacteriophage D3. J. Bacteriol. 155:203-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laing, F. P. Y., K. Ramotar, R. R. Read, N. Alfieri, A. Kureishi, E. A. Henderson, and T. J. Louie. 1995. Molecular epidemiology of Xanthomonas maltophilia colonization and infection in the hospital environment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:513-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lech, K., and R. Brent. 1987. Plating lambda phage to generate plaques, p. 1.11.1-1.11.4. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, et al. (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Levine, M. M., E. J. Bergquist, D. R. Nalin, D. H. Waterman, R. B. Hornick, C. R. Young, and S. Sotman. 1978. Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stabile enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet i:1119-1122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Lucchini, S., F. Desiere, and H. Brussow. 1999. Comparative genomics of Streptococcus thermophilus phage species supports a modular evolution theory. J. Virol. 73:8647-8656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukashin, A. V., and M. Borodovsky. 1998. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1107-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. Coenye, J. W. Chung, D. P. Speert, J. R. W. Govan, P. Taylor, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Diagnostically and experimentally useful panel of strains from the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:910-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Manzenink, O. I., N. V. Volozhantsev, and E. A. Svetoch. 1994. Identification of Pseudomonas mallei bacteria with the help of Pseudomonas pseudomallei bacteriophages. Microbiologiia 63:537-544. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGovern, T. W., G. W. Christopher, and E. M. Eitzen. 1999. Cutaneous manifestations of biological warfare and related threat agents. Arch. Dermatol. 135:311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKevitt, A. I., S. Bajaksouzian, J. D. Klinger, and D. E. Woods. 1989. Purification and characterization of an extracellular protease from Pseudomonas cepacia. Infect. Immun. 57:771-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller, W. R., L. Pannell, L. Cravitz, W. A. Tanner, and T. Rosebury. 1948. Studies on certain biological characteristics of Malleomyces mallei and Malleomyces pseudomallei. II. Virulence and infectivity for animals. J. Bacteriol. 55:127-135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minett, F. C. 1959. Glanders (and melioidosis), p. 296-318. In A. W. Stableforth (ed.), Infectious diseases of animals. Diseases due to bacteria. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 50.Mongkolsuk, S., S. Rabibhadana, P. Vattanaviboon, and S. Loprasert. 1994. Generalized and mobilizabile positive-selection cloning vectors. Gene 143:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neubauer, H., H. Meyer, and E. J. Finke. 1997. Human glanders. Revue Internationale des Services de Santé des Forces Armées 70:258-265. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohnishi, M., K. Kurokawa, and T. Hayashi. 2001. Diversification of Escherichia coli genomes: are bacteriophages the major contributors? Trends Microbiol. 9:481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli 0157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perry, M. B., L. L. MacLean, T. Schollaardt, L. E. Bryan, and M. Ho. 1995. Structural characterization of the lipopolysaccharide O antigens of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 63:3348-3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rahme, L. G., E. J. Stevens, S. F. Wolfort, J. Shao, R. G. Tompkins, and F. M. Ausubel. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Redfearn, M. S., N. J. Palleroni, and R. Y. Stanier. 1966. A comparative study of Pseudomonas pseudomallei and Bacillus mallei. J. Gen. Microbiol. 43:293-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Redfearn, M. S., and N. J. Palleroni. 1975. Glanders and melioidosis, p. 110-128. In W. T. Hubbert, W. F. McCulloch, P. R. Schnurrenberger, (ed.), Diseases transmitted from animals to man. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

- 58.Roberts, R. J. 1990. Restriction enzymes and their isoschizomers. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:2331-2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogul, M., J. J. Brendle, D. K. Haapala, and A. D. Alexander. 1970. Nucleic acid similarities among Pseudomonas pseudomallei,. Pseudomonas multivorans, and Actinobacillus mallei. J. Bacteriol. 101:827-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosebury, T., and E. A. Kabat. 1947. Bacterial warfare. A critical analysis of the available agents, their possible military applications, and the means for protection against them. J. Immunol. 56:7-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 62.Segonds, C., T. Heulin, N. Marty, and G. Chabanon. 1999. Differentiation of Burkholderia species by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and application to cystic fibrosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2201-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Semsey, S., B. Blaha, K. Koles, L. Orosz, and P. Papp. 2002. Site-specific integrative elements of rhizobiophage 16-3 can integrate into proline tRNA (CGG) genes in different bacterial genera. J. Bacteriol. 184:177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]