Abstract

We have studied the roles of the auxiliary protein HypA and of its homolog HybF in hydrogenase maturation. A mutation in hypA leads to the nearly complete blockade of maturation solely of hydrogenase 3 whereas a lesion in hybF drastically but not totally reduces maturation and activity of isoenzymes 1 and 2. The residual level of matured enzymes in the hybF mutant was shown to be due to the function of HypA; HybF, conversely, was responsible for a minimal residual activity of hydrogenase 3 in the mutant hypA strain. Accordingly, a hypA ΔhybF double mutant was completely blocked in the maturation process. However, the inclusion of high nickel concentrations in the medium could restore limited activity of all three hydrogenases. The results of this study and of previous work (M. Blokesch, A. Magalon, and A. Böck, J. Bacteriol. 189:2817-2822, 2001) show that the maturation of the three functional hydrogenases from Escherichia coli is intimately connected via the activity of proteins HypA and HypC and of their homologs HybF and HybG, respectively. The results also support the suggestion of Olson et al. (J. W. Olson, N. S. Mehta, and R. J. Maier, Mol. Microbiol. 39:176-182, 2001) that HypA cooperates with HypB in the insertion of nickel into the precursor of the large hydrogenase subunit. Whereas HypA is predominantly involved in the maturation of hydrogenase 3, HybF takes over its function in the maturation of isoenzymes 1 and 2.

The incorporation of nickel into the metal center of nickel-dependent enzymes like ureases, CO dehydrogenases, or hydrogenases requires the activities of a complex set of accessory proteins. Functions in which they may be involved are nickel transport and intracellular acquisition, donation of the nickel to the apoprotein, release of the nickel donor from the apoprotein after liberation of the metal, chaperone-like activity to maintain a certain folding state amenable to metal insertion, and triggering of a conformational switch to internalize the completed metal center (reviewed in references 9, 22, 28, and 46). Although the metal centers of urease, CO dehydrogenase, and hydrogenase differ considerably in their structures and catalytic roles, some of their auxiliary proteins share similarities both in amino acid sequence and in function. The most conspicuous one is the HypB protein, which is required for hydrogenase maturation; it is homologous to the urease maturation protein UreG and the CO dehydrogenase auxiliary protein CooC. These homologs bind guanosine and adenosine nucleotides, respectively, and their GTP/ATP hydrolysis is essential for nickel insertion (14, 23, 29, 43). Additionally, it was shown elsewhere for urease and CO dehydrogenase that a nickel binding protein exists (UreE and CooJ) which possesses a stretch of His residues similar to that present in some HypB variants (10, 15, 18). Another intriguing characteristic is that their function, when abolished by mutation, can be chemically compensated for by the inclusion of high nickel concentrations in the medium (15, 44, 47).

The main auxiliary proteins required for [NiFe]-hydrogenase maturation are the products of the hyp genes (hypA, hypB, hypC, hypD, hypE, and hypF) and of a gene coding for a specific endopeptidase (hyaD, hybD, or hycI in Escherichia coli) which proteolytically removes a C-terminal extension from the respective large subunit once the metal center is completed (13, 20, 35). Mutational studies have shown that proteins HypB, HypD, HypE, and HypF are involved in the maturation of hydrogenases 1, 2, and 3 of E. coli whereas proteins HypA and HypC act only in the hydrogenase 3 system (13). For HypC, the basis of the specificity lies in the fact that the operon coding for hydrogenase 2 (hyb) contains a gene (hybG [25]) whose function can take over the task of hypC in the maturation of hydrogenases 1 and 2 (3). In addition the maturation of hydrogenase 1 can also be brought about by HypC itself.

hypA is a second gene which has a homolog—as judged by sequence similarity—in the hyb operon, namely, hybF (25). HypA and HybF are very rich in cysteine residues, and their function has not been defined. A recent and intriguing finding, however, is that HypA and HypB are both required for development of urease plus hydrogenase activity in Helicobacter pylori and that lesions in these genes can be fully (urease) and partially (hydrogenase) compensated for by an excess of nickel in the medium (30). In this paper it is shown that HybF—like HybG—ties the maturation of hydrogenase 2 to that of hydrogenase 1 and that under certain physiological conditions there is a functional interplay between HypA and HybF. It is also shown that, in a hypA ΔhybF double mutant, high nickel concentrations in the medium can partially restore the maturation of all three hydrogenases, which indicates a function of the gene products in nickel incorporation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Chromosomal DNA of MC4100, which was used as the wild-type strain, was taken as the template for amplification of the hybF gene via PCR. The respective primers were hybF265upBamHI and hybF186down, as shown in Table 2. The 802-bp PCR fragment was blunt end ligated into the EcoRV restriction site of pACYC184, leading to plasmid pAHBF. A deletion of 252 bp in hybF was introduced by inverse PCR on pAHBF with the oligonucleotides delhybF5′and delhybF3′ (Table 2). The resulting plasmid, pADHBF, was treated with BamHI, and the 749-bp fragment was subcloned into the BamHI-restricted pMAK700 vector. The corresponding plasmid pMDHBF was used to generate the chromosomal in-frame deletion of hybF by the method of Hamilton et al. (11). The parental strains were MC4100 and SMP101, from which DHB-F and DPABF were obtained.

TABLE 1.

List of strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | F− (φ80dlacZΔM15) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | 48 |

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 ptsF25 deoC1 relA1 flbB5301 rpsL150 λ− | 6 |

| SMP101 | MC4100, ATG codon of hypA mutated into TAA | 13 |

| HD705 | MC4100 ΔhycE | 37 |

| DHB-F | MC4100 ΔhybF | This work |

| DPABF | SMP101 ΔhybF | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMAK700 | Cmr | 11 |

| pACYC184 | Cmr Tcr | 7 |

| pBR322 | Apr Tcr | 5 |

| pAHBF | pACYC184 hybF Cmr | This work |

| pADHBF | pACYC184 with 252-bp deletion in hybF; Cmr | This work |

| pMDHBF | pMAK700 with 252-bp deletion in hybF; Cmr | This work |

| pBHBF-Strep | pBR322 hybF-StreptagII Apr | This work |

| pJA101 | pACYC184 hypA Cmr | 13 |

| pR537H | pACYC184 hycE (A1612G, T1613A), hycF′; Cmr | 45 |

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Designation | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| hybF265upBamHI | 5′-CAAGGATCCCTCTGGCCGCTGCGCAAAGTG-3′ |

| hybF186down | 5′-GCTCATGGCAAATCCGACGTGTACCAGCAC-3′ |

| hybFC-StrepII | 5′-CACTTTTCAAACTGAGGGTGGCTCCATTCAACTCAATAC-3′ |

| delhybF5′ | 5′-ATAGACGTCATACTACAACTCATGCATTTTCGCCACTC-3′ |

| delhybF3′ | 5′-TATGACGTCTATTGTCCGCTCTGTCACGGC-3′ |

Newly generated restriction sites are printed in boldface.

To generate plasmid pBHBF-Strep, a 640-bp fragment was ligated into the EcoRV restriction site of pBR322. This fragment was acquired by PCR with the primers hybF265upBamHI and hybFC-StrepII with pAHBF as template.

Growth conditions.

E. coli cells were cultivated anaerobically at 37°C in buffered TGYEP medium (2) supplemented with 15 mM sodium formate. To obtain high-level expression of hydrogenase 2, glucose was omitted from the TGYEP medium, and instead glycerol was added to a final concentration of 0.8%, as well as 15 mM sodium fumarate. Sodium molybdate (1 μM) and sodium selenite (1 μM) were used as supplements. The standard nickel concentration was 5 μM if not indicated otherwise. When needed, the antibiotics chloramphenicol and ampicillin were added to the medium at 20 to 30 and 50 μg/ml, respectively. The cultures were harvested after reaching an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 and stored at −20°C. Crude extracts were obtained as described previously (8).

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

To separate proteins, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed according to the method of Laemmli (16). For analyzing the processing state of the large subunits of hydrogenase 2 (HybC) or 3 (HycE), the proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and reacted with the respective antibodies. The antisera were used at a dilution of 1:1,500 for anti-HybC and 1:1,000 for anti-HycE.

In vivo nickel incorporation experiments.

To examine in vivo nickel incorporation, cells were grown anaerobically in 100 ml of TGYEP medium containing 120 nM 63Ni2+ (specific activity, 642 mCi/mmol; NEN Life Science Products, Inc.). After harvesting and washing of the cells, crude extracts were prepared by sonication and subsequent centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography after separation over 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels as described previously (8). Exposition was for 2 to 4 weeks.

Determination of hydrogenase activity.

Total hydrogenase activity of crude extracts was measured by H2-dependent reduction of benzylviologen according to the procedure of Ballantine and Boxer (1). To highlight active hydrogenases 1 and 2 in polyacrylamide gels, activity staining was performed. For this purpose, 30 μg of crude extract protein was electrophoretically separated in SDS gels (10%) for 4 h at 4°C. All buffers contained SDS at a final concentration of 0.1%, which maintains the compact active structure of hydrogenases 1 and 2, similar to the situation with the hydrogenase of Azotobacter vinelandii as described by Seefeldt and Arp (42). The gels were subsequently incubated in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.5 mM benzylviologen and 1 mM triphenyl tetrazolium chloride under an H2 atmosphere for 16 to 36 h. Hydrogenase 3 activity cannot be visualized by this staining method, probably because of the lability of this isoenzyme under such conditions (39).

RESULTS

Genomic organization of the operons involved in hydrogenase formation in E. coli.

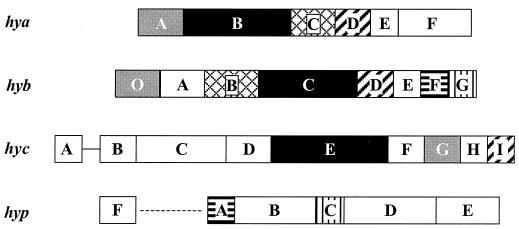

For an overview Fig. 1 displays the gene composition and organization of the hya (26), hyb (25), hyc (4), and hyp (20) operons. The large subunits are encoded by hyaB (hydrogenase 1), hybC (hydrogenase 2), and hycE (hydrogenase 3), and the small subunits are encoded by hyaA, hybO (36), and hycG, respectively. hyaC and hybB code for a cytochrome b for the periplasmic, membrane-bound hydrogenases 1 and 2. Each large subunit requires a specific endopeptidase for the cleavage of the C-terminal extension once the metal center has been incorporated. Their genes are hyaD (27), hybD (25), and hycI (34) for hydrogenases 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In the operon coding for the structural subunits of hydrogenase 2, there are two genes, hybF and hybG, coding for accessory proteins with high sequence similarity to HypA and HypC, respectively (13, 25). As predicted in silico, it was shown that HybG fulfills the role of HypC in the maturation of hydrogenases 1 and 2 (3).

FIG. 1.

Organization of the operons hya, hyb, hyc, and hyp. Homologous genes have the same type of shading. Black boxes, large subunit genes; gray boxes, small subunit genes; hatched boxes, genes for the specific endopeptidases; crosshatched boxes, genes for cytochrome b; vertically striped boxes, genes for HypC and its homolog HybG; horizontally striped boxes, genes for HypA and its homolog HybF.

Properties of HypA and HybF.

The hypA gene of E. coli is the promoter-proximal gene of the hyp operon and is transcribed from the σ54-dependent promoter Pp, which requires the FhlA transcriptional activator plus formate for activation (12, 19, 41). As a consequence, it is expressed only under fermentative conditions; transcription of the downstream genes of the hyp operon under nonfermentative conditions takes place from an Fnr-dependent, σ70 promoter located inside the reading frame of hypA (20). hybF, in contrast, is a member of the hyb operon coding for hydrogenase 2 components and is translated from the polycistronic message of this operon (25). HypA has a size of 13 kDa, and HybF has a size of 12.6 kDa. They share 48% sequence identity and 70% sequence similarity. A conspicuous feature is that the two proteins are very rich in cysteine residues: HypA contains 10 cysteine residues and HybF contains 8 cysteine residues, 4 of them in positions conserved in all homologs known thus far.

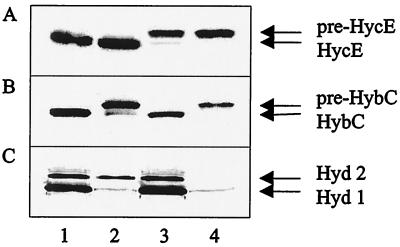

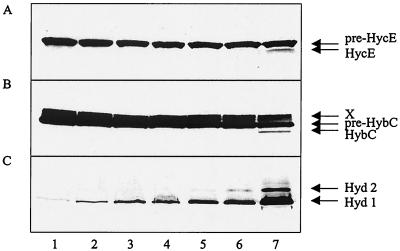

An in-frame deletion was introduced into the chromosomal hybF gene, and the resulting mutant (DHB-F) was analyzed for hydrogenase maturation and activity in comparison to those from a mutant (SMP101) lacking hypA expression and from the hypA ΔhybF double mutant DPABF (Fig. 2). Maturation was assessed by monitoring the proteolytic processing of the precursors of the large subunits for hydrogenase 3 (pre-HycE) (Fig. 2A) and for hydrogenase 2 (pre-HybC) (Fig. 2B). Hydrogenase activity was monitored by H2-dependent benzylviologen reduction after SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2C). The ΔhybF lesion inhibited processing of pre-HybC to a great extent; however, there was still a weakly processed band visible. This is paralleled by the fact that the hypA mutation also did not fully block the maturation of pre-HycE (Fig. 2A, lane 3). In the double mutant, neither of the two precursors was processed at all. Hydrogenase 1 and 2 activity was severely reduced in the ΔhybF background and, with the exception of a trace of hydrogenase 1 activity, was abolished in the hypA ΔhybF strain. As had been shown previously (13), the hypA mutation of strain SMP101 abolished hydrogenase 3 activity to a great extent (data not shown). The results displayed in Fig. 2 were supported by semiquantitative measurements of gas production under fermentative conditions. Compared to the wild type, DHB-F exhibited identical activity, SMP101 produced gas at a lower rate and yield, and the double mutant was devoid of activity (results not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblotting analysis of the precursor and mature forms of HycE and HybC in the wild-type strain MC4100 and in hypA and/or hybF mutant strains. Proteins (30 μg of protein from crude extracts) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel electrophoresis and reacted with antibodies against HycE (A) and HybC (B). Lane 1, MC4100; lane 2, DHB-F (MC4100 ΔhybF); lane 3, SMP101; lane 4, DPABF (SMP101 ΔhybF). Panel C displays the corresponding hydrogenase activity staining.

Overproduction of HypA and HybF.

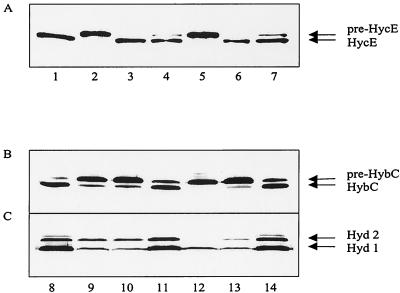

The results in Fig. 2 suggest that HybF promotes maturation of hydrogenases 1 and 2, but they also indicate that HypA may at least partially substitute for the function of HybF and vice versa. Since such functional cross talk should be more predominant when one of the partners is overproduced, the single and double mutant strains were transformed with a plasmid overexpressing either hypA (pJA101) or hybF (pBHBF-Strep). The assessment of hydrogenase maturation in the transformants showed that HybF is functional in hydrogenase 3 maturation (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 7). On the other hand, overproduction of HypA is able to compensate definitely for the defect in hydrogenase 2 maturation at a low level and possibly also for the defect in hydrogenase 1 maturation exhibited by the hybF or the hypA ΔhybF mutant (Fig. 3B, lanes 10 and 13). The determination of hydrogenase 1 and 2 activity present in extracts of the transformants supported these results (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Investigation of the interchangeability of HypA and HybF. Analysis of the processing of HycE (A) (0.15 600-nm optical density units of cells) and HybC (B) (30 μg of total protein) after immunoblotting. The cells used in panel B were additionally analyzed by hydrogenase activity staining (C). Lane 1, MC4100; lane 2, SMP101; lane 3, SMP101/pJA101; lane 4, SMP101/pBHBF-Strep; lane 5, DPABF (SMP101 ΔhybF); lane 6, DPABF/pJA101; lane 7, DPABF/pBHBF-Strep; lane 8, MC4100; lane 9, DHB-F (MC4100 ΔhybF); lane 10, DHB-F/pJA101; lane 11, DHB-F/pBHBF-Strep; lane 12, DPABF (SMP101 ΔhybF); lane 13, DPABF/pJA101; lane 14, DPABF/pBHBF-Strep.

The mutations in hypA and hybF can be compensated for by high external nickel concentrations.

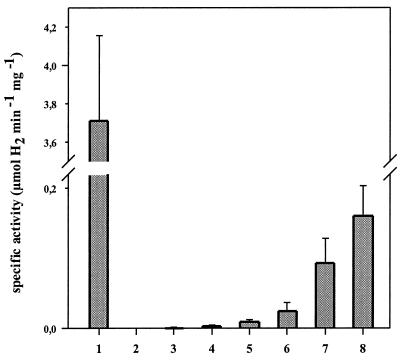

The availability of a hypA ΔhybF mutant and the recent report that HypA from H. pylori may be involved in nickel incorporation into both urease and hydrogenase (30) stimulated the study of whether hydrogenase maturation can be restored chemically by increased nickel concentrations. Extracts from the E. coli hypA ΔhybF mutant cultivated in the presence of different nickel concentrations were tested for H2 oxidation coupled to benzylviologen reduction. The results in Fig. 4 show that hydrogenase activity can be restored to about 4% of the activity of the wild type.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the H2-dependent reduction of benzylviologen by extracts from cells grown in the presence of different nickel concentrations. Crude extracts from the wild type and the hypA ΔhybF mutant DPABF were used for this assay. Lane 1, MC4100; lanes 2 to 8, DPABF. The indicated EDTA and nickel concentrations, respectively, were present in the growth medium: lane 2, 50 μM EDTA; lane 3, 0 μM NiCl2; lane 4, 5 μM NiCl2; lane 5, 20 μM NiCl2; lane 6, 100 μM NiCl2; lane 7, 200 μM NiCl2; lane 8, 400 μM NiCl2. Please note that the ordinate is interrupted from 0.22 to 3.5 and that the maximal recovery is only about 4% in comparison to the wild type.

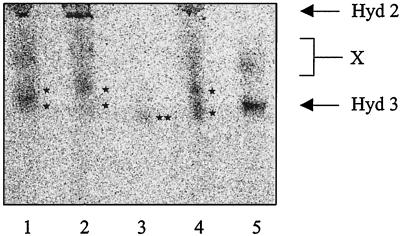

Since this assay predominantly measures hydrogenase 3 activity, we used substrate staining of polyacrylamide gels to test whether the activities of hydrogenases 1 and 2 separated by electrophoresis are also restored (Fig. 5C). This was clearly the case; increasing the metal concentration in the medium leads to a gradual increase of the activity of isoenzymes 1 and 2. Figure 5A and B present the processing of the large subunits of hydrogenases 3 and 2 under these conditions. At the highest nickel concentration employed, the immunoblot visualizes the presence of the processed form of the large subunits. One can conclude, therefore, that to a limited but significant extent nickel replaces the function of the HypA and HybF proteins in the maturation of all three hydrogenases from E. coli.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblotting analysis of the processing ability and hydrogenase activity of the mutant strain DPABF (SMP101 ΔhybF) grown in the presence of different concentrations of EDTA or NiCl2 in the growth medium. Lane 1, 50 μM EDTA; lane 2, 0 μM NiCl2; lane 3, 5 μM NiCl2; lane 4, 20 μM NiCl2; lane 5, 100 μM NiCl2; lane 6, 200 μM NiCl2; lane 7, 400 μM NiCl2. Crude extracts (100 μg of protein) were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by detection with antibodies raised against HycE (large subunit of hydrogenase 3) (A) and HybC (large subunit of hydrogenase 2) (B). Band X indicates nonspecific material. (C) Hydrogenase activity staining of the gel.

Finally, we have measured whether nickel incorporation into the large subunit can be detected in the absence of functional hypA and hybF gene products. Cultures of the control strain MC4100, SMP101 (hypA), DPABF (hypA ΔhybF), and the transformants DPABF/pBHBF-Strep and HD705/pR537H were grown in the presence of radioactive nickel, and extracts were analyzed for 63Ni2+ incorporation after nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6). pR537H is a plasmid which overproduces hydrogenase 3 (45). The S100 extract of strain HD705/pR537H was used as a control to monitor nickel incorporation solely into hydrogenase 3 (E. Theodoratou and A. Böck, unpublished results). The labeling pattern indicates that hydrogenases 1 and 2 contain nickel in the hypA strain (lane 2) but not in the hypA ΔhybF strain (lane 3). When hybF is overexpressed from a plasmid, nickel is incorporated into all three isoenzymes (lane 4). One should note that hydrogenase 1 migrates in a multimeric pattern during purification of hydrogenase 1 as shown before (38). In Fig. 6, band X denotes nickel-containing pre-HycE, which differs greatly in its migration from that of processed HycE (21), and band Y in lane 3 indicates a so-far-unknown signal.

FIG. 6.

In vivo incorporation of 63Ni2+ into hydrogenases 1, 2, and 3. Crude extracts (150 μg of protein, lanes 1 to 4) and S100 extract (150 μg of protein, lane 5) were subjected to nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography for 2 to 4 weeks. Lane 1, MC4100; lane 2, SMP101; lane 3, DPABF (SMP101 ΔhybF); lane 4, DPABF/pBHBF-Strep; lane 5, HD705/pR537H. The migration positions of hydrogenases 2 and 3 are shown by arrows, and the multimeric forms of hydrogenase 1 are denoted by single asterisks; the double asterisk indicates an unidentified nickel signal. X denotes nickel-containing precursors of HycE.

DISCUSSION

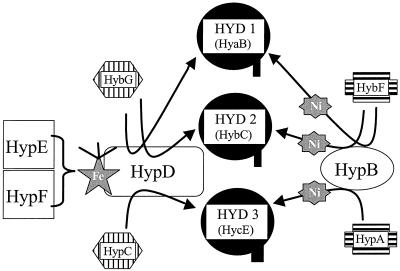

The results obtained in this study complement our previously established network of functional interactions of auxiliary proteins (3), providing the information that HybF has its predominant role in the maturation of hydrogenases 1 and 2. Hydrogenase 3 in contrast can be processed only minimally by the aid of HybF when HypA is missing. In their maturation, isoenzymes 1 and 2 are, therefore, tightly connected by the products of two genes located in the operon for hydrogenase 2, namely, hybF and hybG. In Fig. 7 an extended model of interaction between the auxiliary proteins in the maturation of hydrogenases 1, 2, and 3 is presented. The homologs for HypA and HypC, HybF, and HybG, respectively, are most probably involved in guiding the other Hyp proteins in the direction of hydrogenase 1 and 2 maturation. Under fermentative conditions less HybF and less HybG are present, and therefore, HypA and HypC can predominantly direct the maturation machinery into maturation of hydrogenase 3, which is the major hydrogenase under such growth conditions. Lack of expression of the genes for hydrogenase 2, which is the genuine uptake hydrogenase, would also prevent the maturation of hydrogenase 1, which is supposed to possess a recycling function (40). The minimal cross-function of HybF in the maturation of hydrogenase 3 may be of advantage when cells are shifted from anaerobic respiratory to purely fermentative conditions. It would guarantee a basal level of “HypA function” (which is not formed under anaerobic respiration) and facilitate the rapid adjustment to fermentation.

FIG. 7.

Interactions between the auxiliary proteins in the maturation of hydrogenases 1 (HYD1; HyaB), 2 (HYD2; HybC), and 3 (HYD3; HycE). The model highlights the role of HybG and HybF in guiding the maturation machinery to hydrogenase 1 and 2 maturation under anaerobic respiration. Under fermentative conditions HypC and HypA direct the components to the maturation of hydrogenase 3. The left part represents postulated Fe incorporation by a complex between HypD and HypC/HybG which is followed by the Ni incorporation by HypB and HypA/HybF, shown on the right side. The weak effects of HypA on hydrogenase 1 and 2 maturation and of HybF on hydrogenase 3 maturation as well as the interaction of HypC with hydrogenases 1 and 2 when the homolog is missing are not depicted, for the sake of clarity.

The fact that overproduced HypA can complement the hybF and hypA ΔhybF mutant only slightly whereas HybF complements a hypA and hypA ΔhybF mutant to a considerable extent could be due to a difference in expression level in our experiments. For HybF the overexpression from plasmid pBHBF-Strep can be clearly demonstrated by immunoblotting with antisera raised against the C-terminally fused StreptagII (data not shown). The expression of HypA from plasmid pJA101, on the other hand, can be judged only from the fact that strain SMP101/pJA101 regains full hydrogenase 3 activity (13). Such a difference in expression could affect formation of complexes with other maturation components, which would therefore be titrated. For example, HypC and HybG form a complex with the HypD protein (Fig. 7) (M. Blokesch and A. Böck, unpublished results) as well as with the precursors of the large subunits for hydrogenases 3 and 1 and 2, respectively (3, 8). Another complex exists between HypE and HypF (32; A. Bauer, A. Paschos, and A. Böck, unpublished results) which is crucial for the synthesis of the diatomic ligands CO and CN (31; A. Paschos and A. Böck, unpublished results).

The data presented are also suggestive of a cooperative action of proteins HypA and HybF in nickel incorporation, as suggested recently by Maier and coworkers (30) for HypA of H. pylori. Evidence for such a function came from experiments which showed that the HypC-pre-HycE complex accumulated to almost equal amounts in strains SMP101 (hypA) and DHP-B (ΔhypB) and in a strain devoid of nickel transport (Hyd720) whereas it was strongly reduced in other hyp mutants (8). The results indicated that hydrogenase maturation seems to be blocked at the same step, namely, nickel incorporation. Another argument for this hypothesis is that, like mutations in hypB, lesions in hypA and hybF can be compensated for chemically by high metal concentrations. For hypB mutants, the level of complementation achieved is between 10 and 15% of the specific hydrogenase activity of the wild type; for the hypA ΔhybF mutant it is about 4%. Since HypA and HybF act specifically in the maturation system for hydrogenases 3 and 1 and 2, respectively, in contrast to HypB this may suggest some interaction with the target protein, i.e., the metal-free apoprotein. HypB may provide the energy-yielding step required for nickel insertion. Further analysis is required to detail the specific biochemical role of these proteins and, especially, to delineate whether nickel binding and delivery and GTP hydrolysis are functions of one and the same protein, as previously postulated for HypB (10, 24, 33), or whether they are distributed over two proteins, as in the maturation of urease and CO dehydrogenase (15, 17, 18).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ekaterini Theodoratou for providing the 63Ni2+-labeled S100 extract of strain HD705/pR537H.

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for support of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballantine, S. P., and D. H. Boxer. 1985. Nickel-containing hydrogenase isoenzymes from anaerobically grown Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 163:454-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begg, Y. A., J. N. Whyte, and B. A. Haddock. 1977. The identification of mutants of Escherichia coli deficient in formate dehydrogenase and nitrate reductase activities using dye indicator plates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2:47-50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blokesch, M., A. Magalon, and A. Böck. 2001. Interplay between the specific chaperone-like proteins HybG and HypC in maturation of hydrogenases 1, 2, and 3 from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2817-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Böhm, R., M. Sauter, and A. Böck. 1990. Nucleotide sequence and expression of an operon in Escherichia coli coding for formate hydrogenlyase components. Mol. Microbiol. 4:231-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolivar, F., R. L. Rodriguez, P. J. Greene, M. C. Betlach, H. L. Heyneker, and H. W. Boyer. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1979. Lactose genes fused to exogenous promoters in one step using a Mu-lac bacteriophage: in vivo probe for transcriptional control sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4530-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, A. C., and S. N. Cohen. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drapal, N., and A. Böck. 1998. Interaction of the hydrogenase accessory protein HypC with HycE, the large subunit of Escherichia coli hydrogenase 3 during enzyme maturation. Biochemistry 37:2941-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eitinger, T., and M. A. Mandrand-Berthelot. 2000. Nickel transport systems in microorganisms. Arch. Microbiol. 173:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu, C., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 1995. HypB protein of Bradyrhizobium japonicum is a metal-binding GTPase capable of binding 18 divalent nickel ions per dimer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2333-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton, C. M., M. Aldea, B. K. Washburn, P. Babitzke, and S. R. Kushner. 1989. New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:4617-4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopper, S., and A. Böck. 1995. Effector-mediated stimulation of ATPase activity by the σ54-dependent transcriptional activator FHLA from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:2798-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobi, A., R. Rossmann, and A. Böck. 1992. The hyp operon gene products are required for the maturation of catalytically active hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 158:444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon, W. B., J. Cheng, and P. W. Ludden. 2001. Purification and characterization of membrane-associated CooC protein and its functional role in the insertion of nickel into carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38602-38609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerby, R. L., P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1997. In vivo nickel insertion into the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase of Rhodospirillum rubrum: molecular and physiological characterization of cooCTJ. J. Bacteriol. 179:2259-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, M. H., S. B. Mulrooney, M. J. Renner, Y. Markowicz, and R. P. Hausinger. 1992. Klebsiella aerogenes urease gene cluster: sequence of ureD and demonstration that four accessory genes (ureD, ureE, ureF, and ureG) are involved in nickel metallocenter biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 174:4324-4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, M. H., H. S. Pankratz, S. Wang, R. A. Scott, M. G. Finnegan, M. K. Johnson, J. A. Ippolito, D. W. Christianson, and R. P. Hausinger. 1993. Purification and characterization of Klebsiella aerogenes UreE protein: a nickel-binding protein that functions in urease metallocenter assembly. Protein Sci. 2:1042-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutz, S., R. Böhm, A. Beier, and A. Böck. 1990. Characterization of divergent NtrA-dependent promoters in the anaerobically expressed gene cluster coding for hydrogenase 3 components of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 4:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutz, S., A. Jacobi, V. Schlensog, R. Böhm, G. Sawers, and A. Böck. 1991. Molecular characterization of an operon (hyp) necessary for the activity of the three hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:123-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magalon, A., and A. Böck. 2000. Dissection of the maturation reactions of the [NiFe] hydrogenase 3 from Escherichia coli taking place after nickel incorporation. FEBS Lett. 473:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maier, T., and A. Böck. 1996. Nickel incorporation into hydrogenases, p. 173-192. In R. P. Hausinger, G. L. Eichhorn, and L. G. Marzilli (ed.), Mechanisms of metallocenter assembly. VCH, New York, N.Y.

- 23.Maier, T., A. Jacobi, M. Sauter, and A. Böck. 1993. The product of the hypB gene, which is required for nickel incorporation into hydrogenases, is a novel guanine nucleotide-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 175:630-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier, T., F. Lottspeich, and A. Bock. 1995. GTP hydrolysis by HypB is essential for nickel insertion into hydrogenases of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 230:133-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menon, N. K., C. Y. Chatelus, M. Dervartanian, J. C. Wendt, K. T. Shanmugam, H. D. Peck, Jr., and A. E. Przybyla. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and mutational analysis of the hyb operon encoding Escherichia coli hydrogenase 2. J. Bacteriol. 176:4416-4423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menon, N. K., J. Robbins, H. D. Peck, Jr., C. Y. Chatelus, E. S. Choi, and A. E. Przybyla. 1990. Cloning and sequencing of a putative Escherichia coli [NiFe] hydrogenase-1 operon containing six open reading frames. J. Bacteriol. 172:1969-1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menon, N. K., J. Robbins, J. C. Wendt, K. T. Shanmugam, and A. E. Przybyla. 1991. Mutational analysis and characterization of the Escherichia coli hya operon, which encodes [NiFe] hydrogenase 1. J. Bacteriol. 173:4851-4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobley, H. L., M. D. Island, and R. P. Hausinger. 1995. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol. Rev. 59:451-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moncrief, M. B., and R. P. Hausinger. 1997. Characterization of UreG, identification of a UreD-UreF-UreG complex, and evidence suggesting that a nucleotide-binding site in UreG is required for in vivo metallocenter assembly of Klebsiella aerogenes urease. J. Bacteriol. 179:4081-4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson, J. W., N. S. Mehta, and R. J. Maier. 2001. Requirement of nickel metabolism proteins HypA and HypB for full activity of both hydrogenase and urease in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 39:176-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paschos, A., R. S. Glass, and A. Böck. 2001. Carbamoylphosphate requirement for synthesis of the active center of [NiFe]-hydrogenases. FEBS Lett. 488:9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rain, J. C., L. Selig, H. De Reuse, V. Battaglia, C. Reverdy, S. Simon, G. Lenzen, F. Petel, J. Wojcik, V. Schachter, Y. Chemama, A. Labigne, and P. Legrain. 2001. The protein-protein interaction map of Helicobacter pylori. Nature 409:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rey, L., J. Imperial, J. M. Palacios, and T. Ruiz-Argueso. 1994. Purification of Rhizobium leguminosarum HypB, a nickel-binding protein required for hydrogenase synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 176:6066-6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossmann, R., T. Maier, F. Lottspeich, and A. Böck. 1995. Characterisation of a protease from Escherichia coli involved in hydrogenase maturation. Eur. J. Biochem. 227:545-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossmann, R., M. Sauter, F. Lottspeich, and A. Böck. 1994. Maturation of the large subunit (HycE) of Escherichia coli hydrogenase 3 requires nickel incorporation followed by C-terminal processing at Arg537. Eur. J. Biochem. 220:377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sargent, F., S. P. Ballantine, P. A. Rugman, T. Palmer, and D. H. Boxer. 1998. Reassignment of the gene encoding the Escherichia coli hydrogenase 2 small subunit—identification of a soluble precursor of the small subunit in a hypB mutant. Eur. J. Biochem. 255:746-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauter, M., R. Bohm, and A. Böck. 1992. Mutational analysis of the operon (hyc) determining hydrogenase 3 formation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1523-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawers, R. G. 1985. Membrane-bound hydrogenase isoenzymes from Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom.

- 39.Sawers, R. G., S. P. Ballantine, and D. H. Boxer. 1985. Differential expression of hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli K-12: evidence for a third isoenzyme. J. Bacteriol. 164:1324-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawers, R. G., D. J. Jamieson, C. F. Higgins, and D. H. Boxer. 1986. Characterization and physiological roles of membrane-bound hydrogenase isoenzymes from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:398-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlensog, V., and A. Böck. 1990. Identification and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the transcriptional activator of the formate hydrogenlyase system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1319-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seefeldt, L. C., and D. J. Arp. 1987. Redox-dependent subunit dissociation of Azotobacter vinelandii hydrogenase in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 262:16816-16821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano, A., and R. P. Hausinger. 1999. GTP-dependent activation of urease apoprotein in complex with the UreD, UreF, and UreG accessory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11140-11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sriwanthana, B., M. D. Island, D. Maneval, and H. L. Mobley. 1994. Single-step purification of Proteus mirabilis urease accessory protein UreE, a protein with a naturally occurring histidine tail, by nickel chelate affinity chromatography. J. Bacteriol. 176:6836-6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Theodoratou, E., A. Paschos, S. Mintz-Weber, and A. Böck. 2000. Analysis of the cleavage site specificity of the endopeptidase involved in the maturation of the large subunit of hydrogenase 3 from Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 173:110-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vignais, P. M., B. Billoud, and J. Meyer. 2001. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:455-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waugh, R., and D. H. Boxer. 1986. Pleiotropic hydrogenase mutants of Escherichia coli K12: growth in the presence of nickel can restore hydrogenase activity. Biochimie 68:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodcock, D. M., P. J. Crowther, J. Doherty, S. Jefferson, E. DeCruz, M. Noyer-Weidner, S. S. Smith, M. Z. Michael, and M. W. Graham. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:3469-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]