Abstract

In this study, we established an in-house database of yeast internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. This database includes medically important as well as colonizing yeasts that frequently occur in the diagnostic laboratory. In a prospective study, we compared molecular identification with phenotypic identification by using the ID32C system (bioMérieux) for yeast strains that could not be identified by a combination of CHROMagar Candida and morphology on rice agar. In total, 113 yeast strains were included in the study. By sequence analysis, 98% of all strains were identified correctly to the species level. With the ID32C, 87% of all strains were identified correctly to the species or genus level, 7% of the isolates could not be identified, and 6% of the isolates were misidentified, most of them as Candida rugosa or Candida utilis. For a diagnostic algorithm, we suggest a three-step procedure which integrates morphological criteria, biochemical investigation, and sequence analysis of the ITS region.

Yeast infections are increasing due to the growing number of immunocompromised and severely ill patients (5, 9). In addition, widespread use of antibiotics and invasive procedures facilitate infections with yeasts (18). Although Candida albicans is still the most frequently encountered yeast species, others have gained increasing importance in the last few years (1). Some species, such as Candida krusei (resistance to fluconazole) or Trichosporon sp. (reduced susceptibility to amphotericin B), may show inherent resistance to antimycotics (13). Rapid and accurate identification is thus essential for proper treatment. Various identification methods have been proposed in the past, including morphology, physiological properties, nucleic acid amplification, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and sequencing (2).

For molecular identification, we have chosen sequence analysis since this procedure is simple and can be fully automated. In addition, interpretation of nucleic acid sequences is straightforward and does not depend on too much expertise compared to morphological analyses. As target, we have chosen the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, which is located between the highly conserved genes coding for 18S and 28S rRNA. The ITS encompasses the two noncoding regions ITS1 and ITS2, which are separated by the highly conserved 5.8S rRNA gene (20). The ITS1 and ITS2 regions are more variable than the adjacent rRNA gene sequences and thus promise a better separation of closely related species. As the inspection of yeast ITS sequences which are available in the public database GenBank (NCBI) suggested that some entries are incorrect and because certain medically relevant species are not included, we decided to establish an in-house database. Since the number of known yeast species is enormous, we restricted our database to species occurring in the medical diagnostic laboratory.

In this study, we compared sequence-based identification with conventional identification. Based on these results, we established an algorithm for the effective identification of yeasts in the diagnostic laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conventional identification.

In our mycology laboratory, the identification of yeasts is achieved primarily by phenotypic characteristics. C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis are identified by their morphology on CHROMagar Candida (BD, Basel, Switzerland) combined with micromorphology on rice agar. Other yeast isolates are subjected to biochemical characterization with the ID32C system (bioMérieux, Geneva, Switzerland), and the resulting code is translated into a species with the API biocomputing system (ID32C version 2.0 database; bioMérieux). Identification values of more than 80% are accepted as species or genus identification following recommendations by the manufacturer. As proposed by Tietz et al. (17), strains with the ID32C codes 7046340011 or 7246340011 are identified as Candida africana, a species not included in the ID32C database.

DNA extraction.

Yeast strains were cultivated on Sabouraud agar at room temperature. Two loops full of fungal culture were collected and digested at 37°C for 2 h with 30 U of Lyticase (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Schnelldorf, Germany) in 200 μl digestion buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). Alkaline lysis was performed with the addition of 10 μl 1 M NaOH and 10 μl 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate and incubation for 10 min at 95°C. Following neutralization with 10 μl 1 M HCl, DNA was purified with the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (QIAGEN, Basel, Switzerland) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 200 μl of AL buffer from the kit was added and incubated for 10 min at 70°C. Then, 200 μl of pure ethanol was added, and the whole mixture was loaded on a column. The column was washed twice with the washing buffers from the kit, and the DNA was finally eluted from the column in 100 μl H2O.

Amplification and sequencing.

Amplification was performed in a LightCyler (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) in a volume of 20 μl containing 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM each of primers ITS1 and ITS4 (20), 2 μl of SYBR green master mix, and 2 μl of eluted DNA. Cycling parameters included an initial denaturation for 10 min at 95°C and 50 cycles of 1 sec at 95°C, 5 sec at 53°C, and 40 sec at 72°C. The amplification products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Basel, Switzerland). For construction of the database, sequences were generated with forward primer ITS1 and with backward primer ITS4 and, if necessary, also with forward primer ITS3 and backward primer ITS2, both located in the 5.8S rRNA gene (20). For the clinical isolates, strains were sequenced with forward primer ITS1; in case the forward sequence was not readable, backward primer ITS4 was used for generating the sequence. The BigDye kit (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) and an automated DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer; Applied Biosystems) were used for sequencing.

Construction of the database.

A list covering the majority of the yeasts occurring in the medical diagnostic laboratory was defined. This list covers 48 species from 8 genera and includes all medically important and the most frequent colonizing yeasts (Table 1). For a total of 90 strains (at least one isolate for each species), the ITS region was amplified and both strands were sequenced and assembled to compose the ITS region. The strains originated from quality controls (United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service, Sheffield, United Kingdom), patient isolates, and the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Baarn, The Netherlands) strain collection. The sequences obtained were analyzed together with sequences available in GenBank (NCBI). The SeqWeb version 2.1.0 (web interface to a core set of sequence analysis programs in the GCG Wisconsin package; Accelrys, Cambridge, United Kingdom) evolution program was used to define intra- and interspecies homologies. Sequences that were confirmed by at least one additional independent sequence of the same species (i.e., sequence homology greater than 95%) and that fit well into the similarity tree calculated from the sequence alignment were included in the in-house database. The resulting yeast ITS database is stored in the SmartGene IDNS (Lausanne, Switzerland).

TABLE 1.

Yeast species included in the ITS database, intraspecies homology and number of analyzed sequences

| Speciesa | Intraspecies homology (%) | No. of sequences (in-house/GenBank) |

|---|---|---|

| Candida africana | 99.8-100.0 | 6 (5/1) |

| Candida albicans (S, Candida stellatoidea) | 99.3-100.0 | 22 (4/18) |

| Candida blankii | 100.0 | 2 (0/2) |

| Candida dubliniensis | 99.1-100.0 | 13 (3/10) |

| Candida fabianii (T, Hansenula fabianii, Pichia fabianii) | 1 (0/1) | |

| Candida famata (T, Debaromyces hansenii) | 98.4-100.0 | 11 (1/10) |

| Candida glabrata (S, Torulopsis glabrata) | 98.3-100.0 | 11 (3/8) |

| Candida guilliermondii (T, Pichia guilliermondii) | 99.4-100.0 | 16 (4/12) |

| Candida inconspicua (S, Torulopsis inconspicua) | 98.7-100.0 | 2 (2/0) |

| Candida kefyr (T, Kluyveromyces marxianus) | 99.0-100.0 | 15 (3/12) |

| Candida krusei (T, Issatchenkia orientalis) | 96.4-100.0 | 7 (3/4) |

| Candida lambica (T, Pichia fermentans) | 99.1-100.0 | 4 (2/2) |

| Candida lipolytica (T, Yarrowia lipolytica) | 98.6 | 2 (1/1) |

| Candida lusitaniae (T, Clavispora lusitaniae) | 98.5-100.0 | 11 (4/7) |

| Candida norvegensis (T, Pichia norvegensis) | 99.6-100.0 | 4 (3/1) |

| Candida parapsilosis | 96.7-100.0 | 13 (3/10) |

| Candida pararugosa | 99.5-100.0 | 4 (0/4) |

| Candida pelliculosa (T, Hansenula anomala, Pichia anomala) | 98.4-100.0 | 8 (5/3) |

| Candida rugosa | 94.5-100.0 | 3 (1/2) |

| Candida sorbosa (T, Issatchenkia occidentalis) | 1 (1/0) | |

| Candida tropicalis | 96.2-100.0 | 7 (3/4) |

| Candida utilis (T, Pichia jadinii) | 97.6-100.0 | 6 (2/4) |

| Cryptococcus albidus | 97.0-100.0 | 24 (2/22) |

| Cryptococcus curvatus | 100.0 | 16 (0/16) |

| Cryptococcus humicola | 99.8-100.0 | 9 (0/9) |

| Cryptococcus laurentii group Ia | 99.5-99.8 | 3 (0/3) |

| Cryptococcus laurentii group Ib | 94.2 | 2 (0/2) |

| Cryptococcus laurentii group II | 90.4-97.6 | 4 (0/4) |

| Cryptococcus neoformans (T, Filobasidiella neoformans) | 99.3-100.0 | 30 (4/26) |

| Cryptococcus uniguttulatus (T, Filobasidium uniguttulatum) | 99.8-100.0 | 4 (0/4) |

| Geotrichum candidum (T, Galactomyces geotrichum, Dipodascus australiensis) | 93.5-99.5 | 6 (3/3) |

| Geotrichum capitatum (S, Blastoschizomyces capitatus; T, Dipodascus capitatus) | 99.8-100.0 | 4 (0/4) |

| Malassezia dermatis | 100.0 | 5 (0/5) |

| Malassezia furfur | 98.0-100.0 | 8 (2/6) |

| Malassezia obtusa | 100.0 | 4 (0/4) |

| Malassezia pachydermatis | 100.0 | 3 (2/1) |

| Malassezia restricta | 99.6-100.0 | 5 (0/5) |

| Rhodotorula glutinis (T, Rhodosporium diobovatum) | 96.4-100.0 | 25 (0/25) |

| Rhodotorula minuta | 93.7-100.0 | 29 (0/29) |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | 98.6-100.0 | 32 (2/30) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 97.5-100.0 | 28 (1/27) |

| Saccharomyces kluyveri | 98.3-100.0 | 7 (0/7) |

| Sporobolomyces holsaticus (T, Sporidiobolus johnsonii) | 99.1-100.0 | 6 (0/6) |

| Sporobolomyces salmonicolor (T, Sporidiobolus salmonicolor) | 99.1-100.0 | 10 (1/9) |

| Sporobolomyces roseus | 99.6-100.0 | 10 (0/10) |

| Trichosporon asahii | 98.9-100.0 | 11 (3/8) |

| Trichosporon asteroides | 99.1-100.0 | 4 (0/4) |

| Trichosporon cutaneum | 100.0 | 3 (1/2) |

| Trichosporon inkin | 100.0 | 3 (1/2) |

| Trichosporon mucoides | 99.1-100.0 | 10 (4/6) |

| Trichosporon ovoides | 99.6-100.0 | 4 (1/3) |

S, synonym; T, teleomorph.

Prospective study.

To determine the quality of conventional identification procedures which rely on visual interpretation of CHROMagar Candida and morphology on rice agar, four to five strains each of C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis were sequenced.

Between June and November 2003, all clinical isolates subjected to ID32C were also investigated by sequence determination. The resulting sequence was visually compared with the electropherogram, corrected, and analyzed using the SmartGene IDNS custom platform with the in-house yeast ITS database. Undetermined nucleotides (designated N′s) in the reference sequence were counted as mismatches. The isolate was assigned to a species if the sequence revealed a homology of ≥97% (over the whole length of the sequence) to a reference sequence (depending on the intraspecies homology), and if the next species showed less than 95% homology over the whole length of the sequence. If the comparison with the in-house database did not allow species assignment, the sequence was compared with GenBank using the FASTA algorithm of the GCG Wisconsin package (Accelrys, Cambridge, United Kingdom). The results of the sequence analysis and the ID32C test were compared, and discrepant results were resolved by additional morphological criteria.

RESULTS

Generation of the database.

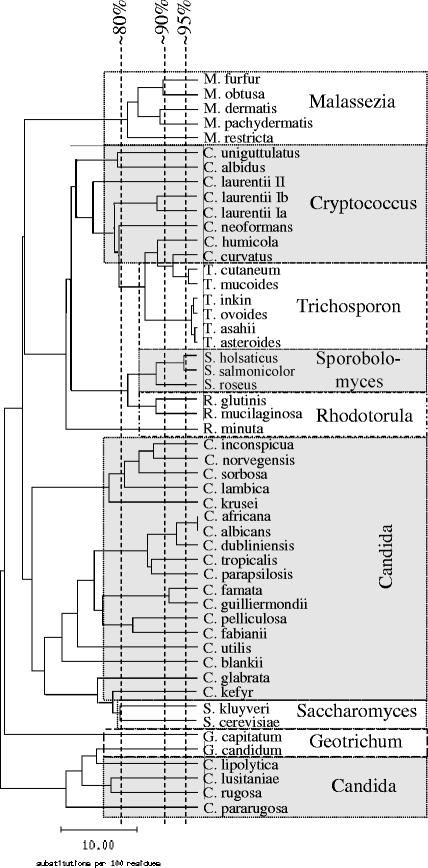

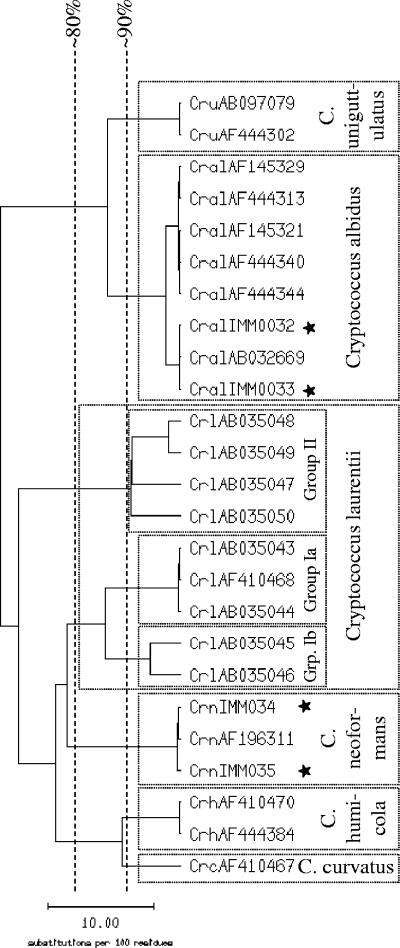

The database consists of 184 sequences representing 48 species from 8 genera (Table 1). Intraspecies homology for 42 of the 48 species is ≥97%. Most species included in our database can be clearly distinguished from each other, as shown in Fig. 1 and in detail in Table 2. Candida stellatoidea is regarded as a synonym of C. albicans, since these two species cannot be discriminated from each other by the ITS sequence (10). Candida africana is included as a separate species, although it is difficult to discriminate from C. albicans with an interspecies sequence homology of 99.3 to 99.8%, which is almost identical to the intraspecies homology of C. albicans (99.3 to 100.0%). For identification of C. albicans and C. africana, the first reference sequence with no mismatch was accepted as the correct identification. Cryptococcus laurentii was split into three genogroups according to the homology of the ITS region; the genogroups showed high intra- but poor intergroup homologies (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Similarity tree calculated from the alignment of yeast species included in the ITS database (one ITS sequence per species), using SeqWeb version 2.1.0.

TABLE 2.

Intra- and interspecies homology of some Candida species

| % Homology

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. dubliniensis | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. lusitaniae | C. norvegensis | C. tropicalis | |

| C. albicans | 99.3-100.0 | 91.2-94.4 | 67.5-68.4 | 62.1-62.7 | 64.1-67.1 | 65.0-65.4 | 87.0-89.6 |

| C. dubliniensis | 99.1-100.0 | 66.4-68.3 | 61.8-63.2 | 65.1-68.0 | 63.1-64.9 | 86.4-90.2 | |

| C. glabrata | 98.3-100.0 | 56.9-87.9 | 54.5-56.9 | 56.9-57.7 | 67.7-70.1 | ||

| C. krusei | 96.4-100.0 | 53.6-57.1 | 71.9-73.3 | 61.0-62.5 | |||

| C. lusitaniae | 98.5-100.0 | 56.2-58.4 | 63.9-68.5 | ||||

| C. norvegensis | 99.6-100.0 | 60.9-63.0 | |||||

| C. tropicalis | 96.2-100.0 | ||||||

FIG. 2.

Similarity tree calculated from the alignment of Cryptococcus ITS sequences using SeqWeb version 2.1.0. The sequences of Cryptococcus laurentii cluster in three genogroups called group Ia, group Ib, and group II. Sequences with the prefix AB or AF were extracted from GenBank (NCBI); sequences with the prefix IMM and marked with a star were obtained from the strain collection in-house.

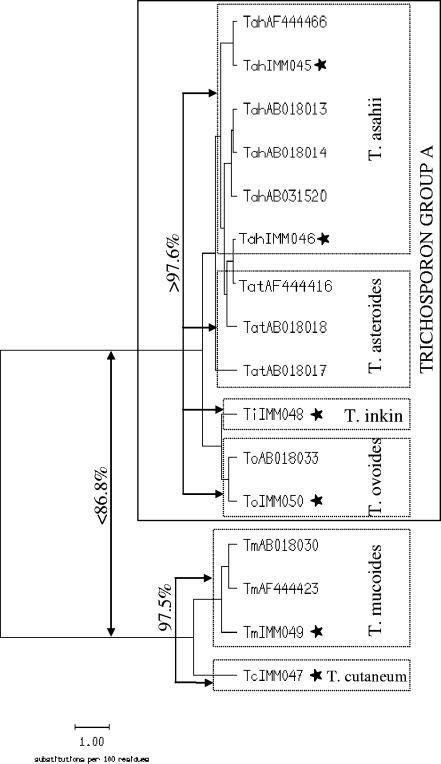

Some of the species included in the in-house database cannot be clearly separated from GenBank entries of other species. Candida guilliermondii cannot be separated from the closely related Candida fermentati (99.0% interspecies homology). Genogroup II of Cryptococcus laurentii, with an intraspecies homology of 90.4 to 97.6% (Fig. 2), is difficult to differentiate from Cryptococcus victoriae (92.5 to 95.9% interspecies homology; data not shown). Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is highly homologous to Rhodotorula dairenensis (97.9 to 98.4% interspecies homology, GenBank sequences). Except for Trichosporon cutaneum and Trichosporon mucoides, Trichosporon species are difficult to distinguish from each other using the ITS sequence (97.6 to 100.0% homology); for the in-house database, we have chosen to summarize these species in Trichosporon group A (Fig. 3). Further, Candida famata, Cryptococcus albidus, Rhodotorula glutinis, Rhodotorula minuta, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae each show high sequence homologies to two or more different species within their genus.

FIG. 3.

Similarity tree calculated from the alignment of Trichosporon ITS sequences using SeqWeb version 2.1.0. The sequences of Trichosporon asahii, T. asteroides, T. inkin and T. ovoides cannot be clearly distinguished from each other, thus, they are combined in the Trichosporon group A. Sequences with the prefix AB or AF were extracted from GenBank (NCBI); sequences with the prefix IMM and marked with a star were obtained from the strain collection in-house.

Prospective study.

During the 6 months of this study, a total of 1,648 yeast strains were subjected to identification. Of these, 1,535 isolates were identified by a combination of CHROMagar Candida and rice agar, resulting in an assignment to one of the four Candida species C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis. Correct identification for four to five representative isolates of each species was confirmed by sequence analysis.

During the 6-month period, 113 isolates could not be identified by phenotypic criteria on CHROMagar Candida and rice agar and were therefore included in this study.

Identification with ID32C.

Using the ID32C system, 70.8% (80 of 113) of the isolates studied were identified to the species level without additional tests. An additional 19.5% (22 of 113) of the isolates were identified by additional tests as recommended by the manufacturer. These additional tests included growth at different temperatures (e.g., 35°C or 40°C), presence of pseudohyphae, and positive reaction for hydrolysis of esculin or urea.

Identification by sequencing.

By sequence determination and comparison with the in-house sequence database, 98% (111 of 113) of the strains were identified to the species level (97.0 to 100.0% homology to the best-matching reference sequence). Only two strains could not be identified due to missing reference sequences in the databases (less than 90% homology to the best match).

Comparison of ID32C and sequencing.

By comparing the two methods, 85.8% (97 of 113) of the results were identical (Table 3). Of these 97 isolates, 96 strains, which were assigned to a species by ID32C, were confirmed by sequencing. One strain could not be identified with either method (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of ID32C and sequence analysis by identification level for 113 isolates

| Identification level | % ID32C (no.) | % Sequence analysis (no.) | % Identical results (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 90.3 (102) | 98.2 (111) | 85.0 (96) |

| Genus | 2.7 (3) | ||

| Not identified | 7.0 (8) | 1.8 (2) | 0.9 (1) |

| Total | 100.0 (113) | 100.0 (113) | 85.8 (97) |

TABLE 4.

Concordant results for ID32C and sequence analysis

| Identification | No. of strains with identical results | Homology (%) to reference sequence (mismatches/sequence length) | Sequence homology (%) to next species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida africana | 5 | 100 (0/511) | 99 to Candida albicans |

| Candida albicans | 3 | 100 (0/511) | 99 to Candida africana |

| Candida dubliniensis | 1 | 100 (0/497) | 91 to Candida albicans |

| Candida glabrata | 17 | 99-100 (0-3/535) | 61 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Candida guilliermondii | 6 | 99-100 (0-4/582) | 87 to Candida famata |

| Candida inconspicua | 6 | 98-100 (0-7/385) | 82 to Candida norvegensis |

| Candida kefyr | 7 | 99 (1/596) | 63 to Candida pelliculosa |

| Candida krusei | 1 | 100 (0/485) | 75 to Candida norvegensis |

| Candida lambica | 1 | 99 (1/419) | 69 to Candida norvegensis |

| Candida lusitaniae | 10 | 99-100 (0-2/357) | 58 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Candida norvegensis | 2 | 100 (0/389) | 82 to Candida inconspicua |

| Candida parapsilosis | 11 | 98-100 (0-7/442) | 81 to Candida tropicalis |

| Candida pelliculosa | 2 | 99 (1/576) | 72 to Candida famata |

| Candida pulcherrimaa | 1 | 98 (6/352) | 76 to Metschnikowia reukaufii |

| Candida tropicalis | 7 | 99 (1-3/500) | 79 to Candida parapsilosis |

| Candida validab | 1 | 99 (2/323) | 76 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 12 | 98-100 (0-7/550) | 61 to Candida glabrata |

| Trichosporon inkin | 1 | 100 (0/514) | 98 to Trichosporon asahii |

| Trichosporon mucoides | 2 | 100 (0/503) | 97 to Trichosporon cutaneum |

| No identification | 1 | 68 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

Not included in the in-house ITS-database, since the two ITS sequences of C. pulcherrima available in GenBank show only 88.8% sequence homology.

Not included in the in-house ITS-database, since at the time of sequence analysis, only one ITS sequence of C. valida was available in GenBank.

Among the 16 strains with discrepant results (Table 5), 7 isolates were not identified by their biochemical profile but by sequencing. For five of these seven strains, sequence analysis revealed a species included in the ID32C system; in two, the isolate was from C. blankii, which is not included in the ID32C database. With ID32C, 2 of 16 strains were identified at the genus level (Candida sp.), whereas sequencing assigned them at the species level (Candida kefyr and Candida lusitaniae). In 7 of 16 cases, strains were misidentified with ID32C. In five of these seven isolates, sequencing revealed a species not included in the ID32C database. These isolates produced a biochemical profile similar to that of a species included in the ID32C; e.g., the biochemical profile of Candida pararugosa is similar to the profile of Candida rugosa. This also applies to Candida fabianii and Candida utilis. However, these species can readily be distinguished by sequence analysis. In two instances, conventional identification was inconsistent with sequence analysis: one strain, identified as Candida glabrata by ID32C, could not be assigned to any species by sequencing. The sequence homology to Candida glabrata was 65.6 to 67.3%. The other strain was slow growing and exhibited morphology compatible with Candida albicans on rice agar. The color on CHROMagar Candida was atypical, therefore an ID32C was performed. The biochemical profile resulted in Zygosaccharomyces sp. (very few reactions were positive), while sequence analysis revealed 100% homology to Candida albicans. Thus, it appears that the strain was misidentified with the ID32C due to slow growth which resulted in weak reactions after 48 h of incubation (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Discrepant results by identification type

| Identification with ID32C | Identification by sequence analysis | Homology (%) to reference sequence (mismatches/sequence length) | Sequence homology to next species | Homology (%) to the species identified with ID32C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida rugosa | Candida pararugosa | 100 (0/390) | 65.4 to Geotrichum candidum | 66.4-67.2 |

| Candida rugosa | Candida pararugosa | 98 (9/391) | 64.9 to Geotrichum candidum | 66.4-67.2 |

| Candida rugosa | Candida pararugosa | 97 (9/364) | 62.7 to Geotrichum candidum | 66.4-67.2 |

| Candida utilis | Candida fabianii | 99 (1/372) | 79.3 to Candida pelliculosa | 83.0-84.0 |

| Candida utilis | Candida fabianii | 98 (6/372) | 78.2 to Candida pelliculosa | 83.0-84.0 |

| Candida glabrata | No identification | 75.3 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 65.6-67.3 | |

| Candida sp. | Candida kefyr | 99 (1/535) | 66.6 to Candida pelliculosa | |

| Candida sp. | Candida lusitaniae | 100 (0/309) | 64.7 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae | |

| Zygosaccharomyces sp.a | Candida albicans | 100 (0/511) | 51.6 to Candida dubliniensis | 54.6-62.0 |

| No identification | Candida blankiib | 99 (1/464) | 88.8 to Candida digboiensis | |

| No identification | Candida blankiib | 99 (1/464) | 88.5 to Candida digboiensis | |

| No identification | Candida glabrata | 99 (1/358) | 44.6 to Saccharomyces cerevisiae | |

| No identification | Candida norvegensis | 97 (7/300) | 88.3 to Candida inconspicua | |

| No identification | Candida parapsilosis | 100 (0/495) | 77.0 to Candida tropicalis | |

| No identification | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 99 (3/388) | 72.7 to Candida glabrata | |

| No identification | Trichosporon mucoides | 100 (0/503) | 57.0 to Trichosporon cutaneum |

The morphology on rice agar was compatible with C. albicans, but the color on CHROMagar Candida was atypical.

Not included in ID32C database.

Considering the additional discriminating criteria, the molecular approach was found to yield the correct identification in all discrepant cases. Overall, 96 of 113 (85%) strains were correctly identified at the species level by ID32C, and 111 of 113 (98%) strains were correctly identified by ITS sequencing (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Final comparison of identification by ID32C versus nucleic acid sequencing

| Comparison parameter | % (No./total no.) of strains

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ID32C | Sequencing | |

| Correct species identification | 85.0 (96/113) | 98.2 (111/113) |

| Correct genus identification | 1.8 (2/113) | |

| Misidentified | 6.2 (7/113) | |

| Not identified | 7.0 (8/113) | 1.8 (2/113) |

DISCUSSION

For the identification of yeasts, various methods are available, including chromogenic substrates (12), micromorphology on rice agar, and biochemical characterizations. For the latter, several products are commercially available, such as Auxacolor (Bio-Rad), Vitek, or API ID32C (bioMérieux). API ID32C covers 62 taxa and was used in the present study. In recent years, several DNA-based molecular identification methods have been established which make use of the variable domains of the 18S or 28S rRNA gene (8, 11). Since the variability of 18S and 28S rRNA genes is limited, it can be difficult to differentiate between species (6). The ITS region, located between the 18S and 28S rRNA genes, is more promising for species discrimination because of its higher variability (7). Although attempts to identify fungi by focusing on either the ITS1 or the ITS2 region may be successful for some species and genera (3, 4), analysis of the complete ITS region offers greater promise for molecular identification (4).

The reliability of identification by sequencing not only depends on the length of the sequence determined, but also on the quality and availability of reference sequences. In GenBank, some species cannot be distinguished from others of the same genus by the ITS sequence. It is not always obvious whether failure of discrimination is a result of mislabeling, of close relationship, or of erroneous taxonomic separation. The definition of a species in mycology is complicated (15). One species may have several names given by different mycologists or due to reassignment of a species based on sequence analysis. Today, morphological characteristics have to be supported by molecular analysis before definition of a new species is approved (e.g., see reference 16). High sequence similarity of the ITS regions may be evidence, but it does not provide definite proof for the identity of two taxa. However, for a large majority of species, the similarity tree of the ITS region is identical to the phylogenetic tree, allowing good identification (14).

To avoid the aforementioned problems of identification with GenBank, we generated an in-house ITS database covering medically relevant yeasts and including only confirmed sequences. To evaluate the quality of our database and the efficiency of phenotypic identification, we compared sequencing with biochemical identification by the ID32C system. In our study, correct species identification was achieved in 98% of the strains by sequence analysis and in 85% by ID32C. The ID32C system misidentified 7% of the isolates. Sequencing identified those isolates mainly as species not included in the ID32C database and biochemically similar to a species included in the ID32C database, e.g., C. rugosa and C. pararugosa or C. utilis and C. fabianii.

Most of the strains included in our study belong to the genus Candida sp. (94 of 113), 4 isolates belong to Trichosporon sp., 13 isolates belong to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and 2 strains could not be identified. Other yeast genera such as Malassezia sp. or Rhodotorula sp. are rare in the diagnostic mycological laboratory (19); these species are, however, included in the in-house database. The vast majority of isolates in the clinical laboratory belong to the species Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis, which can be reliably identified by a combination of morphology on CHROMagar Candida and rice agar, as confirmed by the sequencing of strains with typical phenotypic characteristics.

Results of sequence analysis can be expected within two working days. The results of the ID32C identification system are available after 24 h of incubation, but readings need to be confirmed after 48 h since some strains may show delayed growth. Weak growth with certain substrates makes the resulting identification dependent on the duration of incubation, on individual interpretation, and on the possibility of confirmation by morphology. Sequence analysis, on the other hand, leads to unambiguous identification, but comprises several steps (DNA extraction, amplification, and sequence analysis) which require more hands-on time than the preparation and reading of an ID32C test strip.

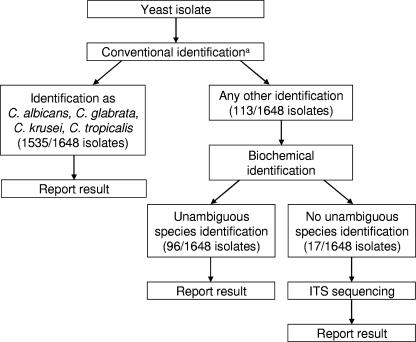

Based on the results of this study, we have implemented the following algorithm in our diagnostic mycology laboratory (Fig. 4). Yeast strains are first grown on chromogenic agar and on rice agar. Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis, in general, can be reliably identified by their morphology (>90% of clinical isolates), although the misidentification of C. dubliniensis as C. albicans is possible. Strains with no specific morphology (5 to 10% of clinical isolates) are subjected to biochemical analysis. If no unambiguous species identification is obtained (about 1% of clinical isolates) and if a correct species identification is of concern, we proceed to sequence determination of the ITS region. This algorithm implements both the cost-effectiveness and precision of analysis that are required in the diagnostic laboratory.

FIG. 4.

Diagnostic algorithm. The numbers in bracket are based on applying this algorithm to the study isolates. a, combination of chromogenic agar and rice agar.

This is the first study comparing the widely used ID32C system to molecular identification in a more systematic approach. We conclude that the ID32C system is easy to perform and has a reasonable accuracy (85%). Sequencing, on the other hand, is more accurate (98%). It requires more hands-on time than the ID32C system, but is not dependent on individual interpretation and expertise. Following the defined algorithm, sequencing is required for about 1% of clinical isolates for optimal identification.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technicians in our laboratory for their valuable help. This work was supported by research grant no. 54230401 from the University of Zürich to P. B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal, J., S. Bansal, G. K. Malik, and A. Jain. 2004. Trends in neonatal septicemia: emergence of non-albicans Candida. Indian Pediatr. 41:712-715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, S. C. A., C. L. Halliday, and W. Meyer. 2002. A review of nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests for systemic mycoses with an emphasis on polymerase chain reaction-based assays. Med. Mycol. 40:333-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, Y. C., J. D. Eisner, M. M. Kattar, S. L. Rassoulian-Barrett, K. LaFe, S. L. Yarfitz, A. P. Limaye, and B. T. Cookson. 2000. Identification of medically important yeasts using PCR-based detection of DNA sequence polymorphisms in the internal transcribed spacer 2 region of the rRNA genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2302-2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, Y. C., J. D. Eisner, M. M. Kattar, S. L. Rassoulian-Barrett, K. LaFe, U. Bui, A. P. Limaye, and B. T. Cookson. 2001. Polymorphic internal transcribed spacer region 1 DNA sequences identify medically important yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4042-4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggimann, P., J. Garbino, and D. Pittet. 2003. Epidemiology of Candida species infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed patients. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:685-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fell, J. W., T. Boekhout, A. Fonseca, G. Scorzetti, and A. Statzell-Tallman. 2000. Biodiversity and systematics of basidiomycetous yeasts as determined by large-subunit rDNA D1/D2 domain sequence analysis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1351-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwen, P. C., S. H. Hinrichs, and M. E. Rupp. 2002. Utilization of the internal transcribed spacer regions as molecular targets to detect and identify human fungal pathogens. Med. Mycol. 40:87-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtzman, C. P., and C. J. Robnett. 1997. Identification of clinically important ascomycetous yeasts based on nucleotide divergence in the 5′ end of the large-subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1216-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maertens, J., M. Vrebos, and M. Boogaerts. 2001. Assessing risk factors for systemic fungal infections. Eur. J. Cancer Care 10:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahrous, M., A. D. Sawant, W. R. Pruitt, T. Lott, S. A. Meyer, and D. G. Ahearn. 1992. DNA relatedness, karyotyping and gene probing of Candida tropicalis, Candida albicans and its synonyms Candida stellatoidea and Candida claussenii. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makimura, K., S. Y. Murayama, and H. Yamaguchi. 1994. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungi by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:358-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odds, F. C., and R. Bernaerts. 1994. CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1923-1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2004. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4419-4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scorzetti, G., J. W. Fell, A. Fonseca, and A. Statzell-Tallman. 2002. Systematics of basidiomycetous yeasts: a comparison of large subunit D1/D2 and internal transcribed spacer rDNA regions. FEMS Yeast Res. 2:495-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor, J. W., D. J. Jacobson, S. Kroken, T. Kasuga, D. M. Geiser, D. S. Hibbett, and M. C. Fisher. 2000. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Gen. Biol. 31:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Than, V. N., M. S. Smit, N. Moleleki, and J. W. Fell. 2004. Rhodotorula cycloclastica sp. nov., Rhodotorula retinophila sp. nov., and Rhodotorula terpenoidalis sp. nov., three limonene-utilizing yeasts isolated from soil. FEMS Yeast Res. 4:857-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tietz, H.-J., M. Hopp, A. Schmalreck, W. Sterry, and V. Czaika. 2001. Candida africana sp. nov., a new human pathogen or a variant of Candida albicans? Mycoses 44:437-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tortorano, A. M., L. Caspani, A. L. Rigoni, E. Biraghi, A. Sicignano, and M. A. Viviani. 2004. Candidosis in the intensive care unit: a 20-year survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 57:8-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh, T. J., A. Groll, J. Hiemenz, R. Fleming, E. Roilides, and E. Anaissie. 2004. Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. 10(Suppl. 1):48-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. .In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.