Abstract

Magnetic particles are increasingly used for various biomedical applications because they are easy to handle and separate from biological samples. In this work, a novel anchor molecule was used for targeted protein display onto magnetic nanoparticles. The magnetic bacterium Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 synthesizes intracellular bacterial magnetic particles (BMPs) covered with a lipid bilayer membrane. In our recent research, an integral BMP membrane protein, Mms13, was isolated and used as an anchor molecule to display functional proteins onto BMPs. The anchoring properties of Mms13 were confirmed by luciferase fusion studies. The C terminus of Mms13 was shown to be expressed on the surface of BMPs, and Mms13 was bound to magnetite directly and tightly permitting stable localization of a large protein, luciferase (61 kDa), on BMPs. Consequently, luminescence intensity obtained from BMPs using Mms13 as an anchor molecule was >400 or 1,000 times higher than Mms16 or MagA, which previously were used as anchor molecules. Furthermore, the immunoglobulin G-binding domain of protein A (ZZ) was displayed uniformly on BMPs using Mms13, and antigen was detected by transmission electron microscopy using antibody-labeled gold nanoparticles on a single BMP displaying the ZZ-antibody complex. The results of this study demonstrated the utility of Mms13 as a molecular anchor, which will facilitate the assembly of other functional proteins onto BMPs in the near feature.

Nanoparticles such as quantum dots, gold particles, and magnetic particles recently have attracted research interest because of the uniqueness of their physical properties, and they have been used as immobilization supports (24, 32), probes (1, 4), or catalysts (25). Magnetic particles have been used in various biomedical applications because they are easy to handle and allow the separation of target molecules from reaction mixtures (10, 12, 19, 30). Functional proteins have been assembled onto nanoparticles, and these complexes have been used as recognition materials for biomolecule detection. The method chosen for protein assembly is determined by the surface properties of the particles. Various methods of assembly onto nanoparticles have been reported, such as electrostatic assembly (5), covalent cross-linking (4, 8), avidin-biotin technology (7), or membrane integration (19, 29). The amount and stability of assembled proteins or the percentage of active proteins among assembled proteins are dependent on the method used for coupling. Important requirements for protein assembly are that the matrix should provide an appropriately stable environment for protein function and allow assembly of enough proteins to perform bioassays.

Functional proteins and random peptide libraries have been displayed on the surface of bacteria (13), bacteriophages (3), viruses (11), and yeasts (27), allowing the manipulation of diverse molecules, which provides tremendous applications in environmental and biomedical fields. These techniques have been achieved using anchor molecules to display foreign proteins on the surface of microorganisms. Foreign proteins also have been displayed on the surface of magnetic nanoparticles. Protein display on bacterial magnetic particles (BMPs) was realized by the development of a fusion technique involving anchor proteins isolated from magnetic bacteria (20). Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 synthesizes intracellular nanoparticle-sized (50- to 100-nm) BMPs covered with a lipid bilayer membrane, which have a single magnetic domain of magnetite and exhibit strong ferrimagnetisms. The MagA (46.8-kDa) and Mms16 (16-kDa) proteins have been used as anchor molecules for displaying luciferase (20), acetate kinase (17), protein A (16), the estrogen receptor hormone-binding domain (33), and G protein-coupled receptors (34), respectively. However, the efficiency and stability of proteins displayed on BMPs have been limited, where only one to three molecules of proteins have been assembled onto a single BMP. New anchor molecules are required for the efficient and stable display of foreign proteins on BMPs. Recently, novel proteins tightly bound to BMPs were discovered in T. Matsunaga's laboratory (2). These proteins were highly expressed in the lipid bilayer membrane covering the BMPs.

In this study, the efficient and stable display of the immunoglobulin G (IgG)-binding domain of protein A (ZZ) on BMPs using a novel anchor molecule, Mms13, which was isolated as a protein tightly bound to BMPs, was performed. The anchoring properties of Mms13 onto BMPs were evaluated using luciferase fusion studies, and its anchoring efficiency was compared to that of other anchor molecules, MagA and Mms16. In addition, a sandwich immunoassay was performed on a single BMP displaying ZZ with Mms13 as an anchor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used as a host for gene cloning. Cells were cultured in LB medium containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C. M. magneticum AMB-1 was microaerobically cultured in magnetic spirillum growth medium at 25°C as previously described (15). Microaerobic conditions were established by purging the cultures with argon gas. Cultures for production of BMPs were prepared in 2 volumes in 4-liter flasks or an 8-liter fermentor (31). AMB-1 transformants were cultured under the same conditions using 5-μg/ml ampicillin.

Construction of expression vectors.

The plasmids pUMLC, pUM13L, and pUM13DL were derived from pUMG (Apr; 6.4 kbp) (23). For construction of pUMLC, the gene encoding luciferase was generated by PCR amplification using AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), a primer set consisting of LC1F (5′-ATGCATATGGAAGACGCC-3′) and LC1R (5′-TTACAATTTGGACTTTCCGCC-3′), with pGV-SC (Toyo Ink Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) as a template. The sequence encoding the mms16 promoter (pmms16) was amplified using the primers P16F (5′-ATGCATGCTTTGCCAGTCGC-3′) and P16R (5′-ATGCATGTTATTCCTCCAACCCG-3′) and AMB-1 genomic DNA as a template. (Underlining in the primers described above indicates the NsiI site.) Each PCR fragment was cloned into pGEMTeasy (Promega, Madison, WI), and this plasmid was designated pGEM-pmms16. The fragment containing the luciferase gene was prepared by partial digestion with EcoRI and cloned into EcoRI-digested pUMG. The plasmid construct pUMGLC (Apr; 8.1 kbp) contains an NsiI site upstream of the sequence including the luciferase gene. The fragment carrying pmms16 was prepared by digestion of pGEM-pmms16 with NsiI and cloned into NsiI-digested pUMGLC. This plasmid construct was designated pUMLC (Apr; 8.6 kbp).

For construction of pUM13L and pUM13DL, the fragment containing the luciferase gene was amplified using KOD polymerase (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), primer set LC2F (5′-AATATTAGCGGCctggtgccgcgcggcagcATGGAAGACGCC-3′, where underlined and lowercase letters indicate SspI and thrombin sites, respectively) and LC1R with pGV-SC as a template and then ligated into SspI-digested pUMG. This plasmid then was digested with SspI, and the amplified DNA fragments encoding Mms13 (native) using a primer set consisting of M13F (5′-ATGCATATGCCCTTTCACCTTG-3′, where underlining indicates the NsiI site) and M13R (5′-GGCCAGTTCGTCCCG-3′) or the fragment encoding the first transmembrane domain of Mms13 (dMms13) using the primer set consisting of M13F and M13′R (5′-GCCGACGGTTTCCTTGC-3′), respectively, were introduced into the SspI site. These constructs were digested with NsiI, and the fragments encoding pmms16 were introduced. Each construct was designated pUM13L (Apr; 9.0 kbp) and pUM13DL (Apr; 8.8 kbp).

For the construction of pUM13ZZ, the mms16 promoter and the fragments encoding Mms13 were amplified using a primer set consisting of P16M13F (5′-GCTTTGCCAGTCGCTGCTG-3′) and P16M13R (5′-AATATTGCTGCCGCGCGGCG-3′, where underlining indicates the SspI site) with pUM13L as a template and then ligated into SspI-digested pUMG (pUMGP16M13). The gene encoding the two Z-domains, which are a synthetic analogue of the IgG-binding B domain of protein A of Staphylococcus aureus, were amplified using a primer set consisting of ZZ-F (5′-AACGTAGACAACAAATTCAACAAAGAAC-3′) and ZZ-R (5′-TTAGGGTACCGAGCTCGAATTC-3′), with pRZM (16) as a template. The construction of pUM16L and pUMML for the expression of the fusion proteins Mms16-luciferase and MagA-luciferase have been described previously (34). The above plasmids were transformed into wild-type M. magneticum AMB-1 by electroporation (23).

Subcellular fractionation.

Stationary-phase cultures of wild-type AMB-1 or transformants harboring each plasmid were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g; 10 min at 4°C), resuspended in 40 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and disrupted by three passes through a French press at 1,500 kg/cm2 (Ohtake Works Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The BMP and disrupted cell fractions were separated magnetically with a columnar neodymium-boron (Nd-B) magnet (diameter, 18.0 mm; height, 10.0 mm; 1.3 T). The collected BMPs were washed with HEPES buffer (10 mM) at least 10 times with weak sonication. The concentration of BMPs in suspension was estimated by optical density at 660 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV-2200; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A value of 1.0 corresponded to 172 μg (dry weight) of BMPs per ml. These purified BMPs then were used for the following assays.

Proteins tightly bound to BMPs were extracted as described previously (2). The purified BMPs (6 mg) were incubated three times in 600 μl of 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), and 40 mM Tris base solution with weak sonication to remove membrane-associated proteins; the BMPs were then washed several times with HEPES buffer. To isolate the tightly bound proteins, BMPs were treated with 60 μl of 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in a water bath at 100°C for 30 min.

The cellular membranes and cytoplasm were fractionated as previously described (22). Disrupted cell fractions were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove undisrupted cells. The supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 165,000 × g for 1 h, and the obtained pellet was washed with HEPES buffer and resuspended in PBS buffer.

Western blotting.

Proteins from the cytoplasmic and cell membrane fractions extracted from BMPs (with boiling in 1% SDS) or the BMP fraction were mixed with SDS sample buffer (final concentrations were as follows: 62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 5% sucrose, and 0.002% bromophenol blue), denatured, and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. The gel was blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by electroblotting. For immunostaining of Western blots, anti-luciferase polyclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Promega, Madison, WI) and alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody (1:5,000 dilution, sc-2771; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used. The membrane was developed using BCIP/NBT-Blue (substrate solution; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Measurement of luciferase activity.

The luciferase activity in each fraction was evaluated as previously described (34). The luminescence intensity (λmax = 565 nm) was measured using a Lucy-2 luminescence reader (Aloka Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with measurements taken 1 min after the addition of substrate solution (luciferase assay systems; Promega, Madison, Wis.). Twenty micrograms of BMPs or 1 μg of protein from the cell membrane or cytoplasmic fraction per 50 μl was mixed with 50 μl of substrate solution.

Protease treatment.

BMPs (3 mg) extracted from AMB-1 transformants harboring pUM13L were mixed with 600 μl of thrombin protease solution (100 U/ml; Amersham Bioscience) and shaken at room temperature for 2 h, followed by magnetic separation of BMPs. BMPs treated with protease were washed once with HEPES buffer, the supernatants (100 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of substrate solution, and luminescence intensity was measured. Localization of Mms13-luciferase fusion proteins on the BMPs was analyzed by Western blotting as described above.

Experiments of IgG binding to ZZ-BMPs.

AMB-1 transformants harboring pUM13ZZ were cultured, and BMPs displaying ZZ domains of protein A (ZZ-BMPs) were purified from disrupted cells. The IgG-binding capacity of ZZ-BMPs was evaluated with rabbit IgG antibody. A sample containing 50 μg of ZZ-BMPs was incubated with 100 μl of alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody solution (0.05 to 25 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature with pulsed sonication. The alkaline phosphate-labeled IgG-ZZ-BMP conjugates then were magnetically separated using a Nd-B magnet from unbounded alkaline phosphate-labeled IgG and washed three times with 100 μl PBS with 0.05% Tween 20. After three washes, the BMP-protein conjugates were mixed with 100 μl of Lumi-Phos 530 including Lumigen PPD {4-methoxy-4-[3-(phosphonooxy)phenyl]spiro[1,2-dioxeteane-3,2′ adamantine] disodium salt} (3.3 × 10−4 M) as luminescence substrate for alkaline phosphatase, and the luminescence intensity was measured. Wild-type BMPs were used as a control. To evaluate each single ZZ-BMP, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG was added, and the BMPs were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

To observe the localization of ZZ domains displayed on a single BMP, gold nanoparticle-labeled IgG was used. ZZ-BMPs (500 μg) were reacted with rabbit anti-guinea pig IgG (50 μg/ml; Sigma) for 60 min and washed three times, followed by incubation of rabbit IgG-ZZ-BMPs (10 μg) with 200 μl of gold nanoparticle (5 nm)-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:5 dilution; Sigma) or anti-human IgG antibody (1:5 dilution; Sigma) as a negative control for 60 min. After washing, 1 μl of the gold nanoparticle-labeled IgG-ZZ-BMP conjugate (10 μg/ml) was incubated on grids for several hours. The distribution of gold nanoparticles on BMPs was observed by electron microscopy (H-700H; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) without staining. The gold nanoparticles were counted on 10 BMPs, and the average number of particles per single BMP was calculated.

Sandwich immunoassay on ZZ-BMPs.

Rabbit anti-goat IgG (Sigma) was added to the ZZ-BMPs, and 10 μg of the IgG-ZZ-BMP conjugate was incubated with 100 μl of antigen solution (goat anti-human IgE antibody, 0.1 to 1,000 ng/ml; Sigma) for 60 min. After being washed, gold nanoparticle (10 nm)-labeled anti-goat IgG (1:5 dilution; Sigma) was introduced and incubated for another 60 min. After conjugates were washed and magnetically separated, gold nanoparticles on BMPs were observed by electron microscopy and counted on >50 BMPs.

RESULTS

Display of luciferase onto BMPs using an anchor molecule, Mms13.

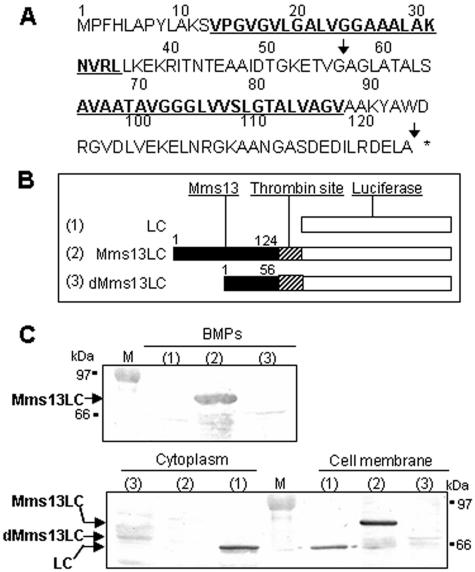

To elucidate the anchoring mechanism of Mms13, which was isolated from tightly binding proteins of BMPs covered with lipid bilayer membrane (2), the secondary structure was analyzed by the computer program SOSUI (http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/sosui_submit.html). The amino acid sequence of Mms13 has two transmembrane helices indicating that Mms13 is localized in the membrane (Fig. 1A). Therefore, luciferase fusion proteins including the native Mms13 (Mms13LC in Fig. 1B) and first transmembrane domain of Mms13 (dMms13) (dMms13LC in Fig. 1B) were constructed. Luciferase was also used as a control (Fig. 1B). BMPs were purified from disrupted cells of AMB-1 transformants harboring plasmid pUMLC, pUM13L, and pUM13DL. Localization of fusion proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C). When native Mms13 was used as an anchor, Mms13-luciferase fusion proteins were observed on BMPs. However, dMms13-luciferase fusion proteins were expressed very poorly and only in the cytoplasmic fraction. Luciferase without an anchor was not localized on BMPs, demonstrating that the second transmembrane domain and C terminus of Mms13 are important for localization onto BMPs.

FIG. 1.

(A) Amino acid sequence of Mms13. Underlining indicates the putative transmembrane domains, and the arrows indicate fusion site with luciferase. (B) The constructions used are shown. Sequences of thrombin site and luciferase were fused to native Mms13 (Mms13LC) or the first transmembrane domain of Mms13 (dMms13LC). (C) Western blots of proteins in BMP membrane, cytoplasmic, and cell membrane fractions, removed from BMPs of AMB-1 transformants harboring pUMLC. Lane 1, LC (luciferase); 61 kDa, pUM13L; lane 2, Mms13LC (Mms13-luciferase fusion protein; 74 kDa) and pUM13DL; lane 3, dMms13LC (dMms13-luciferase fusion protein; 67 kDa). M, molecular mass marker. BMPs (2.5 mg) or proteins (40 μg) of cytoplasmic and cell membrane fractions were treated with SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were denatured and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-luciferase antibody as described in Materials and Methods.

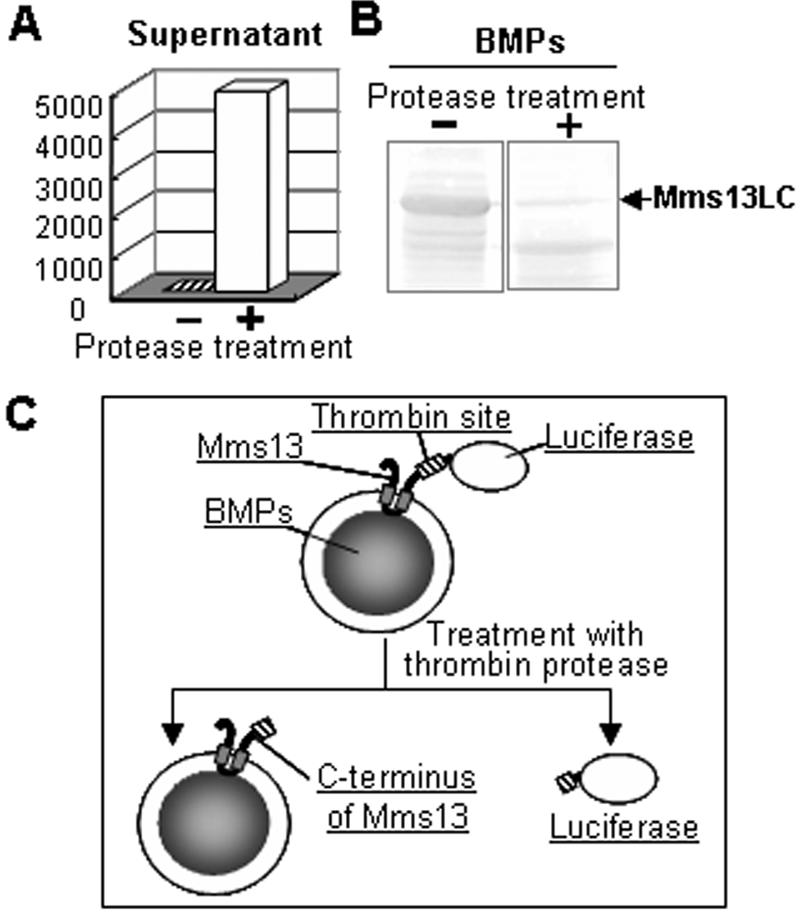

Topology of C terminus of Mms13.

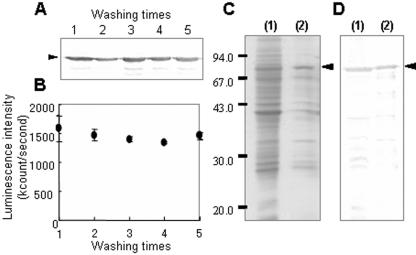

The expression analysis by Western blot showed that Mms13-luciferase was localized on the BMPs (Fig. 1C). However, it was unclear whether the luciferase was surface exposed on BMPs or internally between the magnetite and membrane on BMPs. To address this question, a thrombin recognition site between Mms13 and luciferase was designed (Mms13LC in Fig. 1B) and utilized to determine the orientation of Mms13 in the membrane. BMPs extracted from the AMB-1 transformant harboring pUM13L were treated with thrombin protease. The luminescence intensity of supernatants separated magnetically from BMPs was then measured. High luminescence intensity of the supernatant separated from protease-treated BMPs was obtained (Fig. 2A). Proteolytic cleavage was performed on the surface of BMPs, which showed that the thrombin site and the C terminus of Mms13 were localized on the surface of the BMP membrane. Furthermore, protease-treated BMPs were separated and mixed with SDS buffer to remove the lipid bilayer membrane covering the BMPs. The proteins removed from BMPs in the SDS buffer were analyzed by Western blot using anti-luciferase antibodies (Fig. 2B). The protein bands of Mms13-luciferase were dramatically decreased by the addition of protease, indicating that the fusion protein was largely digested (>90%). The data indicate that the C terminus of Mms13 is localized on the surface of BMP membrane (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Topology of the C terminus of Mms13 on BMPs identified by proteolytic cleavage. (A) Luminescence intensity of supernatant (100 μl) magnetically separated from BMPs treated without (−) or with (+) thrombin protease (100 U/ml). (B) Western blot of proteins removed from BMPs treated with protease. After being washed with HEPES buffer, BMPs (2.5 mg) were mixed with SDS sample buffer, and the eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Schematic diagram showing the reaction of BMPs and thrombin protease.

Stability of Mms13-luciferase integrated into the lipid bilayer membrane covering the BMPs.

Washing and magnetic separation of the BMP suspension used for the bioassays could result in mechanical disruption of the BMPs. Furthermore, the accuracy of the bioassay could be affected by the stability of fusion proteins integrated into lipid bilayer membrane covering BMPs. Therefore, the stability of Mms13-lucifease fusion proteins in the BMP membrane during washing was evaluated. The results from Western blot analysis of proteins removed from lipid bilayer membrane covering BMPs and measurements of luminescence intensity of BMPs displaying luciferase showed constant localization of Mms13-luciferase fusion proteins on BMPs, even though the large protein luciferase (61 kDa) was fused to Mms13 (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

Stability of Mms13-luciferase integrated into the lipid bilayer membrane covering BMPs. (A) Western blot analysis of proteins removed from the lipid bilayer membrane covering BMPs. BMPs (2.5 mg) were mixed with SDS sample buffer, and the eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Luminescence intensity of BMPs (20 μg) after washing by pipetting and magnetic separation. (C) SDS-PAGE profile. (D) Western blot analysis of proteins extracted from BMPs with boiling 1% SDS solution. Proteins were extracted from BMPs before (lanes 1) and after (lanes 2) treatment with a solution containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 4% CHAPS proteins. Proteins (30 μg) removed from BMPs with boiling 1% SDS solution were used in the experiments shown in panels C and D. Arrowheads indicate Mms13-luciferase.

In previous studies (18, 21, 22), it was found most proteins on BMPs, except proteins that bind tightly to magnetite, could be removed by treatment with buffer containing urea. BMPs displaying luciferase before and after treatment with a solution containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 4% CHAPS were immersed in boiling 1% SDS solution, and the proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3C) and Western blotting using anti-luciferase antibodies (Fig. 3D). When protein fractions before and after treatment with the solution were compared, it was found that most of the proteins on the BMPs were dissolved by the treatment. Conversely, Mms13-luciferase fusion proteins showed stable localization on BMPs. The stability of Mms13 on BMPs could be attributed to some interaction between Mms13 and the magnetite surface.

Anchoring efficiency of Mms13, Mms16, and MagA onto BMPs.

The anchoring efficiency of Mms13 onto BMPs was compared to that of Mms16 and MagA, which have been used for protein display on BMPs in previous studies (28, 34). Mms16 is a small hydrophilic protein (16 kDa), while MagA is predicted to be a 12-transmembrane protein (46.8 kDa) with large hydrophobic domains. Mms13-luciferase, Mms16-luciferase, and MagA-luciferase were expressed in AMB-1 transformants under the control of the mms16 promoter. Luciferase activity of each cellular fraction was measured; the data are summarized in Table 1. Total expression of luciferase (cell debris in Table 1) was different between transformants although the same promoter was used in all of the constructs. The luminescence intensity of cellular debris expressing Mms13-luciferase was 3.4 times higher than Mms16-luciferase. Furthermore, the luminescence intensity of BMPs using Mms13 was >400 times higher than that observed with Mms16. A large amount of luciferase was targeted and displayed on BMPs, and Mms13 behaved as an efficient anchor molecule.

TABLE 1.

Luminescence intensity of cell fractions from AMB-1 transformants harboring each plasmida

| Fraction | Plasmid (anchor)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pUM13L (mms13) | pUM16L (mms16) | pUMML (magA) | |

| Cell debris | 318.8 | 93.6 | 8.3 |

| Cytoplasm | 37.3 | 165.7 | 3.7 |

| Cell membrane | 154.8 | 1.4 | 15.1 |

| BMPs | 3,008.3 | 7.5 | 3.0 |

Units are kilocounts per second per microgram of protein of each fraction. The substrate (50 μl) was added into each fraction (1 μg of proteins or 20 μg of BMPs/50 μl). BMP membrane proteins constituted 3% of the total mass weight of BMPs.

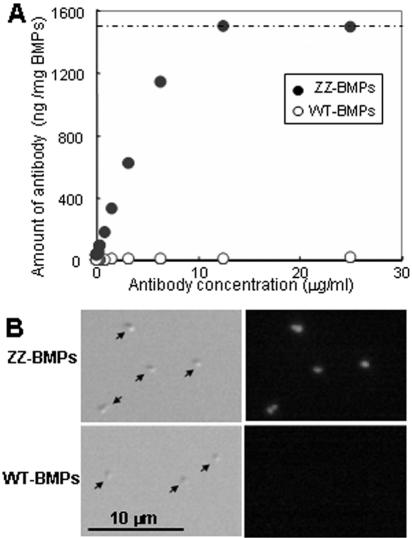

Display of the IgG-binding domain of protein A onto BMPs using Mms13.

Mms13 was used as an anchor molecule for the display of a functional protein, the IgG-binding domains of staphylococcal protein A (ZZ) on the surface of BMPs. Mms13-ZZ fusion proteins were assembled onto BMPs; display of ZZ on BMPs was confirmed with alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody (Fig. 4A). Nonspecific adsorption of antibody to BMPs extracted from wild-type AMB-1 was not detected, while the saturation-binding curve of antibodies to BMPs extracted from transformants harboring pUM13ZZ (ZZ-BMPs) was obtained; approximately 1,500 ng of antibodies was introduced onto 1 mg of ZZ-BMPs.

FIG. 4.

Display of ZZ on BMPs using Mms13. (A) Saturation binding curve of alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG bound to BMPs. (B) Differential interference microscopy imaging and fluorescence microscopy imaging of BMPs after introduction of TRITC-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG. WT-BMPs, BMPs extracted from wild-type AMB-1; ZZ-BMPs, BMPs extracted from AMB-1 transformant harboring pUM13ZZ.

To demonstrate that ZZ was displayed on all of the BMPs extracted from transformants, TRITC-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody was added, and single BMPs were observed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4B). Single BMPs were observed by differential interference imaging (Fig. 4B, left). Sufficient fluorescence for the clear observation of individual ZZ-BMPs was generated (Fig. 4B, right), and the antibody was present on all BMPs (>50 particles were observed). The data indicate that ZZ was functionally displayed on all BMPs.

Furthermore, distribution of the displayed ZZ among single BMPs was visualized using gold nanoparticle-conjugated antibodies by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Rabbit IgG was added to ZZ-BMPs (rabbit IgG-ZZ-BMPs), and gold nanoparticle (5 nm)-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Ab-A) or anti-human IgG antibodies (Ab-B; negative control) were added. After repeated washes were done, gold nanoparticle-labeled antibodies on rabbit IgG-ZZ-BMP conjugates were observed by TEM (Fig. 5). The detection of gold nanoparticles on BMPs using Ab-A indicated the presence of displayed ZZ (Fig. 5A) because the gold nanoparticles were not observed with Ab-B, which cannot recognize rabbit IgG (Fig. 5B). Gold nanoparticles on single BMPs were counted and averaged 21.8 ± 7.9 particles per BMP (average of 10 BMPs).

FIG. 5.

TEMs of ZZ-BMPs introduced to rabbit IgG after addition of gold nanoparticle (5 nm)-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Ab-A) (A) or anti-human IgG antibodies (Ab-B) (B).

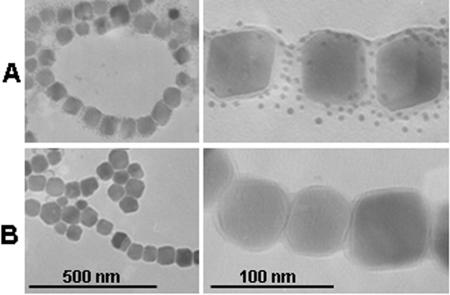

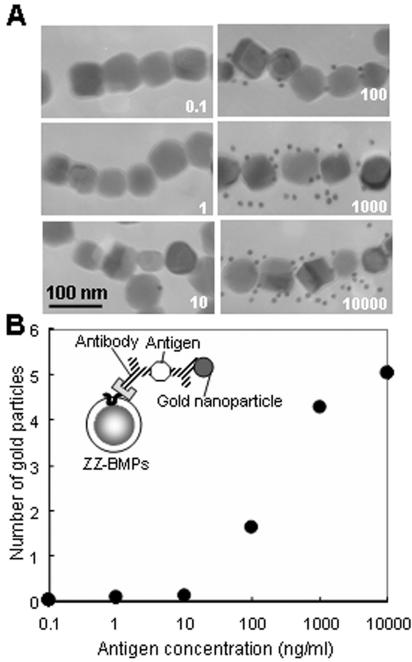

Relationship between antigen concentration and number of gold nanoparticles on a single BMP.

When various concentrations of antigen (goat IgG) were reacted with antibody (anti-goat IgG antibodies), the number of gold nanoparticles conjugated to the secondary antibody (anti-goat IgG antibodies) were measured by TEM. Anti-goat IgG antibodies were added to ZZ-BMPs, and anti-goat IgG-ZZ-BMP conjugates were incubated with various concentrations of antigen solution (goat IgG; 0.1 to 10,000 ng/ml). After being washed, gold nanoparticle (10 nm)-labeled anti-goat IgG antibodies were added. After washing, the number of gold nanoparticles on a BMP complex at each concentration of antigen was counted (Fig. 6A). The number of gold nanoparticles observed increased with increasing concentrations of antigen. The gold nanoparticles were counted on >50 BMPs, and the average number of particles per a single BMP was calculated (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrate the possibility of using a single BMP in a sandwich immunoassay. Under the experimental conditions used here, the detectable concentration of antigen was in the range of 10 to 1,000 ng/ml.

FIG. 6.

Observation of sandwich immunoassay on ZZ-BMPs by TEM. (A) TEM of BMPs after sandwich immunoassay. Anti-goat IgG antibody-ZZ-BMP complexes were mixed with antigen (goat IgG, 0.1 to 10,000 ng/ml), followed by gold nanoparticle (10 nm)-labeled anti-goat IgG antibody. (B) Relationship between antigen concentration and number of gold nanoparticles on a single BMP. The number of gold nanoparticles was counted on >50 BMP samples.

DISCUSSION

BMPs have been utilized for a number of environmental or clinical applications, and DNA and proteins have been immobilized onto BMPs by cross-linking methods (14, 35) or assembled by genetic engineering and fusion techniques with membrane-integrated or -attached proteins, which guided target proteins onto the surface of BMPs (12, 28, 34). These techniques permit preservation of protein activity and simple preparation of functional protein-BMP complexes. In this study, Mms13, which was used as an anchor molecular for efficient and stable display of functional proteins onto BMPs, was characterized, and its anchoring properties were evaluated. Mms13 showed no sequence similarity to known functional proteins, and the only observed similarity was to the BMP membrane protein MamC from Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense (9). The secondary structure of Mms13 (124 amino acids) was predicted to have two transmembrane domains. The results of luciferase fusion and proteolytic cleavage studies confirmed that the C-terminal of Mms13 is surface exposed on the lipid bilayer membrane covering the BMPs and that the loop region (36LKEKRITNTEAAIDTGKETVGAGLATALS64) between the first and second transmembrane domains is inevitably in the face of the magnetite surfaces. The interaction between the loop domain and magnetite was not identified; however, Mms13 was dominant in the fraction obtained by boiling and SDS treatment, and the protein solution showed a yellowish color, indicating the presence of iron, which was observed in previous studies (2).

In magnetic bacteria, BMP membrane vesicles are thought to originate from invagination of the cytoplasmic membrane (6, 21). Therefore, the following hypothesis of Mms13 membrane trafficking is proposed: initially, the N terminus of Mms13 is localized to the cytoplasmic side, membrane trafficking of the first and second transmembrane domains occurs, and then the C terminus of Mms13 localizes to the cytoplasmic side again. Invagination of the cytoplasmic membrane and magnetite formation proceed in vesicles; consequently, the C and N termini of Mms13 are surface exposed on BMPs. It has been suggested that Mms13 plays an important role in crystal formation and that the loop domain is bound tightly to magnetite. Consequently, functional proteins fused to the C terminus of Mms13 might be stably localized on BMPs. A large number of techniques for the display of proteins onto the outer membranes of microorganisms have been investigated and achieved using anchor proteins. The maximum size and stability of displayed proteins on the outer membrane of microorganisms are determined by anchor protein properties (26). Stable display of proteins of >50 kDa on the outer membrane of microorganisms usually is difficult. In the case of BMPs, large proteins like luciferase (61 kDa) were stably displayed onto the lipid bilayer membrane covering magnetic nanoparticles.

We demonstrated the efficient and stable display of ZZ onto BMPs, and an immunoassay using single ZZ-BMPs was performed. It has been found that approximately 20 antibodies can be consistently assembled on a single ZZ-BMP. The number of assembled antibodies enabled us to observe and count antigen-bound gold nanoparticles through TEM images. The ability to observe and count the antigen-bound gold nanoparticles is a novel method and suggests that antibody-antigen binding was successfully observed at the molecular level, leading to high sensitivity. Furthermore, from the careful observation of TEM images, gold nanoparticles were located away from BMP surfaces at maximal distances of 20 nm for the results shown in Fig. 5A and 30 nm for the data shown in Fig. 6A. Since the size of the antibody is assumed to be 10 nm, these distances are feasible for the sandwich immunoassay.

The ZZ-BMPs developed in this study can be used in a variety of applications. BMPs are excellent biomaterials for use in fully automated systems employing magnetic separation. These systems facilitate rapid buffer exchange and stringent washing and reduce nonspecific binding, which may interfere with analysis. Mms13 is a novel molecular anchor that has strong potential for display of different type of functional proteins onto magnetic nanoparticles.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (2), no. 13002005 from the Scientific Research for the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerman, M. E., W. C. Chan, P. Laakkonen, S. N. Bhatia, and E. Ruoslahti. 2002. Nanocrystal targeting in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12617-12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakaki, A., J. Webb, and T. Matsunaga. 2003. A novel protein tightly bound to bacterial magnetic particles in Magnetospirillum magneticum strain AMB-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8745-8750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clackson, T., H. R. Hoogenboom, A. D. Griffiths, and G. Winter. 1991. Making antibody fragments using phage display libraries. Nature 352:624-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao, X., Y. Cui, R. M. Levenson, L. W. Chung, and S. Nie. 2004. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:969-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman, E. R., G. P. Anderson, P. T. Tran, H. Mattoussi, P. T. Charles, and J. M. Mauro. 2002. Conjugation of luminescent quantum dots with antibodies using an engineered adaptor protein to provide new reagents for fluoroimmunoassays. Anal. Chem. 74:841-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorby, Y. A., T. J. Beveridge, and R. P. Blakemore. 1988. Characterization of the bacterial magnetosome membrane. J. Bacteriol. 170:834-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gref, R., P. Couvreur, G. Barratt, and E. Mysiakine. 2003. Surface-engineered nanoparticles for multiple ligand coupling. Biomaterials 24:4529-4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grubisha, D. S., R. J. Lipert, H. Y. Park, J. Driskell, and M. D. Porter. 2003. Femtomolar detection of prostate-specific antigen: an immunoassay based on surface-enhanced Raman scattering and immunogold labels. Anal. Chem. 75:5936-5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunberg, K., E. C. Muller, A. Otto, R. Reszka, D. Linder, M. Kube, R. Reinhardt, and D. Schuler. 2004. Biochemical and proteomic analysis of the magnetosome membrane in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1040-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu, H., P. L. Ho, K. W. Tsang, L. Wang, and B. Xu. 2003. Using biofunctional magnetic nanoparticles to capture vancomycin-resistant enterococci and other gram-positive bacteria at ultralow concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:15702-15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kratz, P. A., B. Bottcher, and M. Nassal. 1999. Native display of complete foreign protein domains on the surface of hepatitis B virus capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1915-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhara, M., H. Takeyama, T. Tanaka, and T. Matsunaga. 2004. Magnetic cell using antibody binding with protein A expressed on bacterial magnetic particles. Anal. Chem. 76:6207-6213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, J. S., K. S. Shin, J. G. Pan, and C. J. Kim. 2000. Surface-displayed viral antigens on Salmonella carrier vaccine. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:645-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama, K., H. Takeyama, E. Nemoto, T. Tanaka, K. Yoda, and T. Matsunaga. 2004. Single nucleotide polymorphism detection in aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) gene using bacterial magnetic particles based on dissociation curve analysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87:687-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsunaga, T., T. Sakaguchi, and F. Tadokoro. 1991. Magnetite formation by a magnetic bacterium capable of growing aerobically. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:651-655. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsunaga, T., R. Sato, S. Kamiya, T. Tanaka, and H. Takeyama. 1999. Chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay using protein A-bacterial magnetite complex. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 194:126-131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsunaga, T., H. Togo, T. Kikuchi, and T. Tanaka. 2000. Production of luciferase-magnetic particle complex by recombinant Magnetospirillum sp. AMB-1. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 70:704-709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsunaga, T., N. Tsujimura, Y. Okamura, and H. Takeyama. 2000. Cloning and characterization of a gene, mpsA, encoding a protein associated with intracellular magnetic particles from Magnetospirillum sp. strain AMB-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268:932-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirzabekov, T., H. Kontos, M. Farzan, W. Marasco, and J. Sodroski. 2000. Paramagnetic proteoliposomes containing a pure, native, and oriented seven-transmembrane segment protein, CCR5. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:649-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura, C., T. Kikuchi, J. G. Burgess, and T. Matsunaga. 1995. Iron-regulated expression and membrane localization of the magA protein in Magnetospirillum sp. strain AMB-1. J. Biochem. 118:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamura, Y., H. Takeyama, and T. Matsunaga. 2001. A magnetosome-specific GTPase from the magnetic bacterium Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48183-48188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura, Y., H. Takeyama, and T. Matsunaga. 2000. Two-dimensional analysis of proteins specific to the bacterial magnetic particle membrane from Magnetospirillum sp. AMB-1. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 84-86:441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamura, Y., H. Takeyama, T. Sekine, T. Sakaguchi, A. T. Wahyudi, R. Sato, S. Kamiya, and T. Matsunaga. 2003. Design and application of a new cryptic-plasmid-based shuttle vector for Magnetospirillum magneticum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4274-4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phadtare, S., V. P. Vinod, P. P. Wadgaonkar, M. Rao, and M. Sastry. 2004. Free-standing nanogold membranes as scaffolds for enzyme immobilization. Langmuir 20:3717-3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad, B. L., S. I. Stoeva, C. M. Sorensen, V. Zaikovski, and K. J. Klabunde. 2003. Gold nanoparticles as catalysts for polymerization of alkylsilanes to siloxane nanowires, filaments, and tubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:10488-10489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuelson, P., E. Gunneriusson, P. A. Nygren, and S. Stahl. 2002. Display of proteins on bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 96:129-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shusta, E. V., M. C. Kieke, E. Parke, D. M. Kranz, and K. D. Wittrup. 1999. Yeast polypeptide fusion surface display levels predict thermal stability and soluble secretion efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 292:949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka, T., and T. Matsunaga. 2000. Fully automated chemiluminescence immunoassay of insulin using antibody-protein A-bacterial magnetic particle complexes. Anal. Chem. 72:3518-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka, T., H. Takeda, Y. Kokuryu, and T. Matsunaga. 2004. Spontaneous integration of transmembrane peptides into a bacterial magnetic particle membrane and its application to display of useful proteins. Anal. Chem. 76:3764-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu, C., K. Xu, H. Gu, X. Zhong, Z. Guo, R. Zheng, X. Zhang, and B. Xu. 2004. Nitrilotriacetic acid-modified magnetic nanoparticles as a general agent to bind histidine-tagged proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:3392-3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, C., H. Takeyama, T. Tanaka, and T. Matsunaga. 2001. Effects of growth medium composition, iron sources and atmospheric oxygen concentrations on production of luciferase-bacterial magnetic particle complex by a recombinant Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 29:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, H. H., S. Q. Zhang, X. L. Chen, Z. X. Zhuang, J. G. Xu, and X. R. Wang. 2004. Magnetite-containing spherical silica nanoparticles for biocatalysis and bioseparations. Anal. Chem. 76:1316-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshino, T., F. Kato, H. Takeyama, M. Nakai, Y. Yakabe, and T. Matsunaga. 2005. Development of a novel method for screening of estrogenic compounds using nano-sized bacterial magnetic particles displaying estrogen receptor. Anal. Chim. Acta 532:105-111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshino, T., M. Takahashi, H. Takeyama, Y. Okamura, F. Kato, and T. Matsunaga. 2004. Assembly of G protein-coupled receptors onto nanosized bacterial magnetic particles using Mms16 as an anchor molecule. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2880-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshino, T., T. Tanaka, H. Takeyama, and T. Matsunaga. 2003. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 gene using a single bacterial magnetic particle. Biosens. Bioelectron. 18:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]