Abstract

Preexposure of Bifidobacterium longum NCIMB 702259T to cholate caused increased resistance to cholate, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin. The B. longum ctr gene, encoding a cholate efflux transporter, was transformed into the efflux-negative mutant Escherichia coli KAM3, conferring resistance to bile salts and other antimicrobial compounds and causing the efflux of [14C]cholate.

Bifidobacteria are major components of the human intestinal microflora (13) and are widely used as probiotics in food supplements. Probiotic survival depends on resistance to antibiotics and to inhibitory host-produced substances, such as bile salts (9). Bifidobacteria are resistant to a range of antibiotic compounds (5), which could allow them to withstand concurrent antibiotic administration. This study aimed to identify and prove the functionality of a possible efflux system encoded by the ctr gene in Bifidobacterium longum which may contribute to bile and antibiotic resistance.

Adaptation to sodium glycocholate and antibiotics.

To determine the intrinsic MICs for B. longum NCIMB 702259T (NCIMB, United Kingdom) of antimicrobial agents, 10 μl of a standard cell suspension (optical density at 600 nm, 0.5) of a culture grown anaerobically on BYG agar (14) was spotted onto BYG plates containing a twofold dilution range of sodium glycocholate, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, or tetracycline. Adaptation to the antibiotics was tested using a method modified from the work of Carsenti-Etesse et al. (4). Mid-exponential-phase B. longum cells grown in BYG broth were streaked for four passages onto sodium glycocholate gradient plates, and the MICs for these cells were tested as described above. Adapted B. longum showed an increase in resistance to sodium glycocholate, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin but not to ampicillin and tetracycline (Table 1). This indicated that B. longum may possess multidrug transporters, since these are often regulated by the compounds that they transport but may confer resistance to structurally unrelated antimicrobial agents (3).

TABLE 1.

MICs of antimicrobial agents tested against B. longum NCIMB 702259a

| Treatment | Antimicrobial MIC

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amp (μg/ml) | Chl (μg/ml) | Cholate (%) | Em (μg/ml) | Tet (μg/ml) | |

| Control | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| Cholate preexposure | 1.6 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

MICs of antimicrobial agents tested against B. longum NCIMB 702259, without (control) and following preexposure to cholate, as determined by plating cells onto BYG plates containing a twofold dilution range of each antibiotic. The antimicrobial agents used were ampicillin (Amp), chloramphenicol (Chl), erythromycin (Em), tetracycline (Tet), and sodium glycocholate (cholate). The experiments were done in triplicate.

Cloning and antimicrobial characterization of the ctr gene.

Open reading frame BL1102 (B. longum NCC 2705, GenBank accession number AE014295) was identified as a possible sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. The BL1102 orthologue was isolated from B. longum NCIMB 702259T genomic DNA (14), using standard PCR protocols and the primers ctrans-F (5′-AGCTGAATTCGCGCAACAGG-3′) and ctrans-R (5′-ACGCCCGGTACCTCAATCG-3′). EcoRI and KpnI restriction enzyme sites (underlined) were introduced to ctrans-F and ctrans-R, respectively, to assist subcloning into pBluescriptSK. The nucleotide sequence of the insert in the recombinant plasmid pCtr was determined (14), and nucleotide and amino acid homology searches were performed using the BLAST algorithm and NCBI databases (1). The deduced amino acid sequence of Ctr was 100% identical to that of BL1102. Plasmid pCtr was transformed into competent (2) Escherichia coli KAM3 (11), a K-12 derivative lacking the multidrug transporter AcrAB. The MICs of acriflavine, sodium dodecyl sulfate (Merck), chloramphenicol, erythromycin, ethidium bromide, tetracycline (Sigma), and sodium glycocholate (Difco) were determined using the broth dilution method (8). Plasmid pCtr conferred cholate resistance on E. coli KAM3, increasing the MIC of sodium glycocholate by 16-fold (Table 2). Resistance to the antimicrobial agents was increased by two- to fourfold.

TABLE 2.

MICs for E. coli KAM3 harboring pCtr and the control vector pBluescriptSK as determined by the broth dilution methoda

| Plasmid | MIC of:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acr (μg/ml) | Chl (μg/ml) | Em (μg/ml) | EtBr (μg/ml) | Cholate (%) | SDS (%) | Tet (μg/ml) | |

| pBluescriptSK | 6.25 | 0.4 | 1.25 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.4 |

| pCtr | 25 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 50 | 8 | 0.02 | 1.6 |

The antimicrobial agents used were acriflavine (Acr), ampicillin (Amp), chloramphenicol (Chl), erythromycin (Em), ethidium bromide (EtBr), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), sodium glycocholate (cholate), and tetracycline (Tet). The experiments were done in triplicate.

Efflux of [14C]cholate.

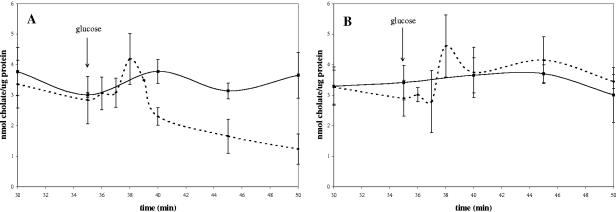

To determine whether pCtr conferred resistance to bile through the active efflux of the compound, de-energized washed cell suspensions of E. coli KAM3 (pCtr or pBluescriptSK) that had been grown to mid-exponential phase in Luria-Bertani broth (14) were preloaded with [carboxyl-14C]cholic acid (New England Nuclear Corp.). The amount of cell-associated radioactivity was monitored with and without the addition of glucose as an energy source. The method of Yokota et al. (17) was used with the following modifications. Washed cells were resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 4, aliquots of 1.94 ml were used in the experiment, and all incubation was at 37°C. To preload the cells with cholate, 40 μl of 5.8 mM [14C]cholate (16 mCi/mmol) was added (final cholate concentration, 0.116 mM). The amount of radioactivity associated with each aliquot was used to calculate the counts per minute per mmol of cholate. The results were expressed as nmol cholate/μg protein, determined using a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). In the absence of glucose, the external and internal cellular cholate concentrations reached equilibrium within 35 min (Fig. 1A and B). Upon the addition of glucose, cholate was transiently accumulated in the presence and absence of pCtr. In the absence of pCtr, an equilibrium was again reached after 40 min (Fig. 1B). When pCtr was present, however, there was a decrease in the level of cell-associated cholic acid (Fig. 1A), indicating an active efflux of cholate. Glucose metabolism results in a slow generation of a pH gradient, which is likely to drive the initial accumulation of cholate. The subsequent activity of the Na+/H+ antiporter results in the generation of a sodium gradient necessary to drive the cholate transporter. This is evidence that the ctr gene of B. longum encodes a cholate efflux transport system that is functional in E. coli.

FIG. 1.

Energy-dependent extrusion of [14C]cholate in E. coli KAM3 harboring (A) pCtr or (B) pBluescriptSK. Cells were preloaded with cholate, and the amount of cell-associated cholate was subsequently measured over time with the addition of glucose (dotted lines) or without glucose (solid lines) Glucose was added to a final concentration of 10 mM at 35 min as indicated by the arrow. During each experiment, samples were taken in triplicate, and the entire experiment was also performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate the deviation from the mean.

Bioinformatic and phylogenetic analysis of the Ctr protein.

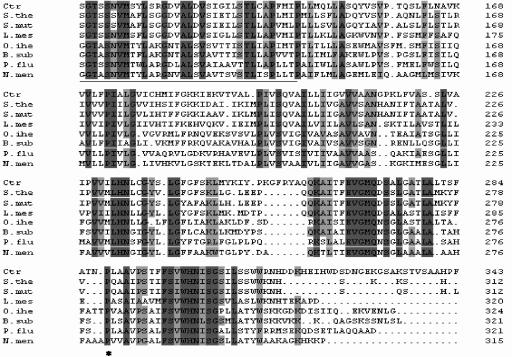

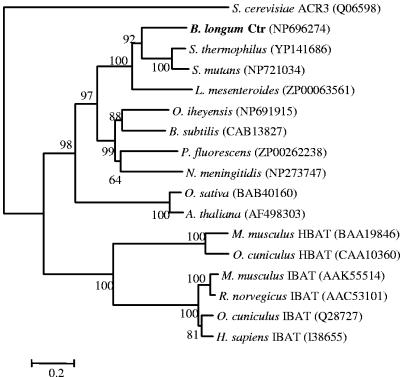

Ctr belongs to the sodium/bile acid family (SBF) of transporters (10), showing the signature motif of this family (Fig. 2). Analysis of the predicted membrane topology revealed the presence of nine transmembrane segments as well as a highly conserved proline residue, corresponding to P290 in the human bile transporter (Fig. 2), which is an essential residue for bile acid transport (15). The phylogenetic relationship of various SBF proteins from different taxa was determined using the neighbor-joining method of ClustalW (Fig. 3). The Ctr protein is closely related to a number of sodium bile acid cotransporter proteins from bacteria, including two Streptococcus species and Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Prior to this study, the members of the SBF family with proved function were all in eukaryotes, and in mammals, these transmembrane proteins are responsible for the cotransport of sodium and bile acids across the plasma membrane in the liver and ileum (6, 7). SBF transporters from plants, namely, Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa (12), form a separate distinct cluster. These are inducible during growth, but neither their efflux function nor their substrates have been established. The ACR3 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an efflux transmembrane protein involved in resistance to arsenic compounds (16).

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of the significant regions of the putative B. longum bile transporter Ctr (GenBank accession no. DQ017587) with closely related bacterial sodium/bile acid transporters. Sequences included are from the following organisms: B. longum (Ctr) (NP_696274), Streptococcus thermophilus (S.the) (YP_141686), Streptococcus mutans (S.mut) (NP_721034), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L.mes) (ZP_00063561), Oceanobacillus iheyensis (O.ihe) (NP_691915), Bacillus subtilis (B.sub) (CAB13827.1), Pseudomonas fluorescens (P.flu) (ZP_00262238.1), and Neisseria meningitides (N.men) (NP_273747). Amino acids conserved in all sequences are shaded in dark gray, and amino acids conserved in over 75% of the sequences are shaded in light gray. The conserved proline residue is indicated by an asterisk, and the SBF signature motif is underlined.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship analysis of bacterial sodium/bile acid transporters, namely, Ctr from B. longum, Streptococcus thermophilus, Streptococcus mutans, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Oceanobacillus iheyensis, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Neisseria meningitidis; the plant sodium/bile acid symporter-like proteins AtSbf1 (Arabidopsis thaliana) and OsSbf1 (Oryza sativa); mammalian ileal sodium/bile acid transporters (IBAT) from Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Oryctolagus cuniculus, and Rattus norwegicus; mammalian hepatic sodium/bile acid transporters (HBAT) from M. musculus and O. cuniculus; and the arsenate resistance protein (ACR3) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Database accession numbers are given in parentheses. The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method, and bootstrap values (250 replicates) are given at the branch points.

In this study we have confirmed that the ctr gene of B. longum encodes a cholate transporter which is responsible for the efflux of cholate from E. coli and confers resistance to a number of structurally unrelated antimicrobial compounds. This is the first characterization of a bile acid transporter of the SBF family in bacteria and the first multidrug transporter to be characterized from a Bifidobacterium species.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the putative B. longum bile transporter Ctr is DQ017587.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) South Africa for financial support of this project. C. E. Price acknowledges an NRF bursary and a University of Cape Town travel scholarship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage, P., R. Walden, and J. Draper. 1988. Vectors for the transformation of plant cells using agrobacterium, p. 46-49. In J. Draper, R. Scott, P. Armitage, and W. Walden (ed.), Plant genetic transformation and gene expression, a laboratory manual. Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 3.Baranova, N. N., A. Danchin, and A. A. Neyfakh. 1999. Mta, a global MerR-type regulator of the Bacillus subtilis multidrug-efflux transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1549-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carsenti-Etesse, H., P.-M. Roger, B. Dunais, S. Durgeat, G. Mancini, M. Bensoussan, and H. Schweizer. 1999. Gradient plate method to induce Streptococcus pyogenes resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:439-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charteris, W. P., P. M. Kelly, L. Morelli, and J. K. Collins. 2000. Effect of conjugated bile salts on antibiotic susceptibility of bile salt tolerant Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium isolates. J. Food Prot. 63:1369-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagenbuch, B., and P. Dawson. 2004. The sodium bile salt cotransporter family SLC10. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 447:566-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagenbuch, B., and P. J. Meier. 1994. Molecular cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional characterization of a human liver Na+ bile salt cotransporter. J. Clin. Investig. 93:1326-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koneman, E. W., S. D. Allen, V. R. Dowell, Jr., W. M. Jando, H. M. Sommer, and W. C. Winn, Jr. 1988. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, p. 473. In E. W. Koneman (ed.), Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 3rd ed. J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 9.Kurdi, P. H. Tanaka, H. van Veen, K. Asano, F. Tomita, A., and Yokota. 2003. Cholic acid accumulation and its diminution by short-chain fatty acids in bifidobacteria. Microbiology 149:2031-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchler-Bauer, A., and S. H. Bryant. 2004. CD-search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W327-W331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita, Y., K. Kodama, S. Shiota, T. Mine, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tscuchiya. 1998. NorM, a putative multidrug efflux protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its homolog in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1778-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rzewuski, G., and M. Sauter. 2002. The novel rice (Oryza sativa L.) gene OsSbf1 encodes a putative member of the Na+/bile acid symporter family. J. Exp. Bot. 53:1991-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon, G. L., and S. L. Gorbach. 1984. Intestinal flora in health and disease. Gastroenterology 86:174-193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trindade, M. I., V. R. Abratt, and S. J. Reid. 2003. Induction of sucrose-utilization genes from Bifidobacterium lactis by sucrose and raffinose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:24-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong, M. H., P. Oelkers, and P. A. Dawson. 1995. Identification of a mutation in the ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter gene that abolishes transport activity. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27228-27234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysocki, R., P. Bobrowicz, and S. Ulaszewski. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACR3 gene encodes a putative membrane protein involved in arsenite transport. J. Biol. Chem. 272:30061-30066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokota, A., M. Veenstra, P. Kurdi, H. W. van Veen, and W. N. Konings. 2000. Cholate resistance in Lactococcus lactis is mediated by an ATP-dependent multispecific organic anion transporter. J. Bacteriol. 182:5196-5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]