Abstract

Vibrios are gram-negative γ-proteobacteria which are ubiquitous in marine and estuarine environments. Recently, we demonstrated that some, if not all, Vibrio species have two circular chromosomes. The whole genome sequence of Vibrio cholerae N16961 has been reported. In this study, we constructed a physical and genetic map of the genome of Kanagawa phenomenon-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus strain KX-V237 and compared it with those of V. parahaemolyticus AQ4673 and V. cholerae N16961. The genome of KX-V237 comprised two circular chromosomes (3.3 and 1.9 Mb), similar to the structure of the AQ4673 genome. The relative positions of the genes on the genomes were well conserved in the two strains, but a large inversion on the large chromosomes, probably symmetric around the replication origin, was suggested. Although the sizes of the large chromosomes of KX-V237 and V. cholerae N16961 were similar, the sizes of the small chromosomes were very different. Unlike N16961, the superintegron of KX-V237 was located on the large chromosome. Comparison of the genetic maps of the chromosomes of KX-V237 and V. cholerae N16961 revealed that most of the open reading frames (ORFs) present on the large chromosome of the V. cholerae strain had homologues on the large chromosome of the V. parahaemolyticus strain and that most of the ORFs on the small chromosome of N16961 were present on the small chromosome of KX-V237. The difference in the orders of the ORFs on the chromosomes of N16961 and KX-V237 implies that numerous and frequent genetic exchanges have occurred intrachromosomally rather than interchromosomally.

Vibrios are gram-negative γ-proteobacteria which are ubiquitous in marine and estuarine environments. Vibrio cholerae (32) is the most clinically important vibrio, because it is the etiological agent of cholera, a severe diarrheal disease that is highly lethal unless it is properly treated. This organism has multiple lifestyles, including a planktonic, free-swimming form, a sessile form attached to zooplankton and other aquatic flora and fauna (6), and a pathogen of host organisms (humans). It also enters a viable but nonculturable state (24) under certain conditions. Recently, it was revealed that some, if not all, Vibrio species, including V. cholerae, have two circular chromosomes (10, 31, 33). Determination of the whole genome sequence of V. cholerae strain N16961 (10) demonstrated that the vast majority of recognizable genes for essential cell functions (such as DNA replication, transcription, translation, and cell wall biosynthesis) and for pathogenicity (for example, genes encoding toxins, surface antigens, and adhesins) are located on the large chromosome. In contrast, the small chromosome contains a higher proportion of hypothetical genes than the large chromosome. Comparing the bias in the gene contents of the two chromosomes, Heidelberg et al. (10) conjectured that under some environmental conditions, there might be a difference in copy number between the chromosomes and that one of the chromosomes may have accumulated genes that are better expressed at a higher or lower copy number than genes on the other chromosome. They also postulated from evidence based on genome sequence information that the small chromosome of V. cholerae may have originally been a megaplasmid that was captured by an ancestral Vibrio species.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, another vibrio, is recognized as a major, worldwide cause of gastroenteritis, particularly in areas of the world where seafood consumption is high (16). This organism is an emerging pathogen in North America (2, 3, 7). Like V. cholerae, this organism has multiple lifestyles in various environments (20). Hemolysis on a special blood agar (Wagatsuma's agar), known as the Kanagawa phenomenon (KP), has been recognized to be strongly associated with human-pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains (26). The hemolysin that causes KP is called the thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) (11). Although much less frequently, KP-negative V. parahaemolyticus strains that produce a toxin named TDH-related hemolysin have also been reported to cause gastroenteritis similar to that caused by TDH-producing isolates (12, 14, 30). Both TDH and TDH-related hemolysin, encoded by the tdh and trh genes, respectively, are now recognized as important virulence factors in the pathogenesis of V. parahaemolyticus (11, 22).

We have previously presented a physical and genetic map of the genome of V. parahaemolyticus strain AQ4673 and demonstrated that it has two circular chromosomes (33). AQ4673 is a KP-negative strain, a comparative rarity among clinical isolates of V. parahaemolyticus. In this study, we analyzed a physical and genetic map of the genome of the KP-positive strain V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237 and compared it with that of AQ4673. We also compared the map with that of V. cholerae N16961 to determine the similarities and differences in the genome structures of two species in the genus Vibrio.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

V. parahaemolyticus strain RIMD2210633 (referred to in this paper as KX-V237) used in this study was isolated at the Kansai International Airport quarantine station in 1996 from a patient with traveler's diarrhea (21). This strain is KP positive and possesses two copies of the tdh gene.

PFGE and FIGE.

Samples of bacterial genomic DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or field inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE) were prepared by a previously described method (15). PFGE was carried out with a CHEF DRIII or CHEF MAPPER system (Bio-Rad). FIGE was performed with a CHEF MAPPER system. The agarose gels used for PFGE or FIGE were 1% pulsed-field-certified agarose (Bio-Rad) or 0.8% chromosomal grade agarose (Bio-Rad) gels.

DNA techniques.

After electrophoresis, nicking of the DNA fragments, transfer of the DNA fragments onto a nylon membrane, and hybridization were done by using previously described procedures (15). The nylon membrane used for DNA transfer was a GeneScreen membrane (NEN Life Science Products). A UV chamber GS Gene Linker (Bio-Rad) was used for nicking DNA fragments in the gels after electrophoresis and for cross-linking the DNA to nylon membranes. The hybridization temperature was 42°C. General DNA techniques, such as digestion of DNA with restriction enzymes and ligation, were performed as previously described (27). Preparation of plasmids from bacterial cells was performed by the alkaline lysis methods (1).

Preparation of linking clones.

Two methods were used in combination to obtain linking clones to construct the physical map of the chromosomes of the V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237 strain. One procedure was a previously described procedure (33). Briefly, to isolate NotI-linking clones, the genomic DNA of the KX-V237 strain was completely digested with the enzyme EcoRI, PstI, SalI, EcoT22I, BanIII, or Mlu I. Each digest was then self-ligated. The resulting circular molecules were linearized by NotI digestion. The linear DNA fragments were cloned into the NotI site of the pBluescript II vector (Stratagene). For use in NotI-linking probes, we characterized the plasmids that were obtained on the basis of the sizes of the inserts and the specificity for hybridizing to the NotI fragments of KX-V237. In the second method, a lambda phage library of genomic DNA of KX-V237 (unpublished data) was used. The insert of each clone in the library (a total of 2,500 clones) was amplified by PCR by using LA Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), and the products were treated with restriction enzyme NotI. Inserts possessing a NotI site were used as linking clones.

Preparation of DIG-labeled DNA probe.

The DNA fragments used as NotI-linking probes were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by using a random primer extension method and a DIG DNA labeling kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The probes used for open reading frames (ORFs) of V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae were prepared by using a PCR DIG labeling kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Sequence data required for PCR primer design were obtained from the DNA Database of Japan and the Comprehensive Microbial Resource of the Institute for Genomic Research. For comparison of the genome structures of V. cholerae N16961 and V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237, DNA probes were obtained as follows. A number of ORFs present on the N16961 genome were selected, and PCR primer sets were designed for these ORFs. By using these primer sets, PCR was carried out with the genomic DNA of KX-V237. From the primer sets with which DNA fragments of the expected sizes were amplified, we selected 42 sets that showed the most even overall distribution across the N16961 genome (see Fig. 4). The amplified PCR products were used to prepare DIG-labeled probes by the method described above.

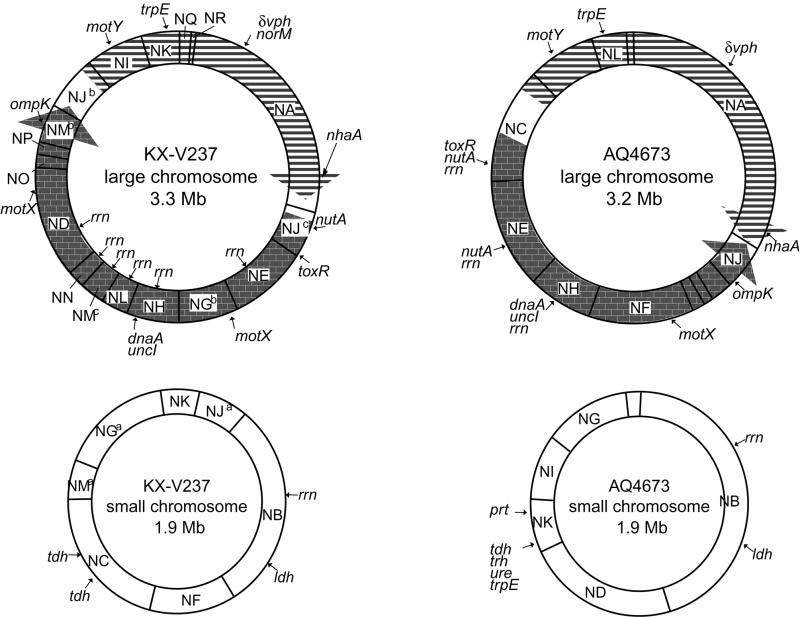

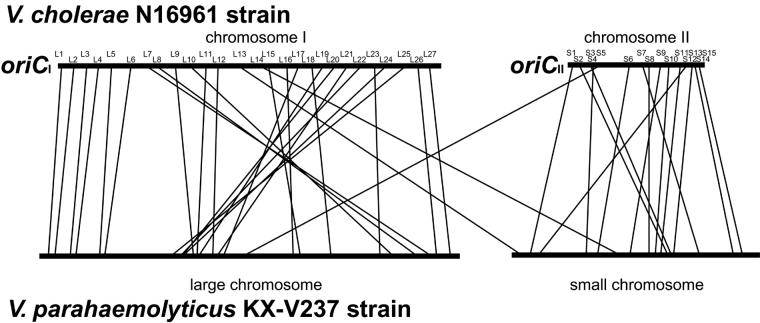

FIG. 4.

Comparison of genetic maps of V. cholerae N16961 and V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237. The ORFs of N16961 corresponding to probes L1 to L27 and S1 to S15 are listed in Table 2.

RESULTS

Construction of a physical map of V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237 chromosomes.

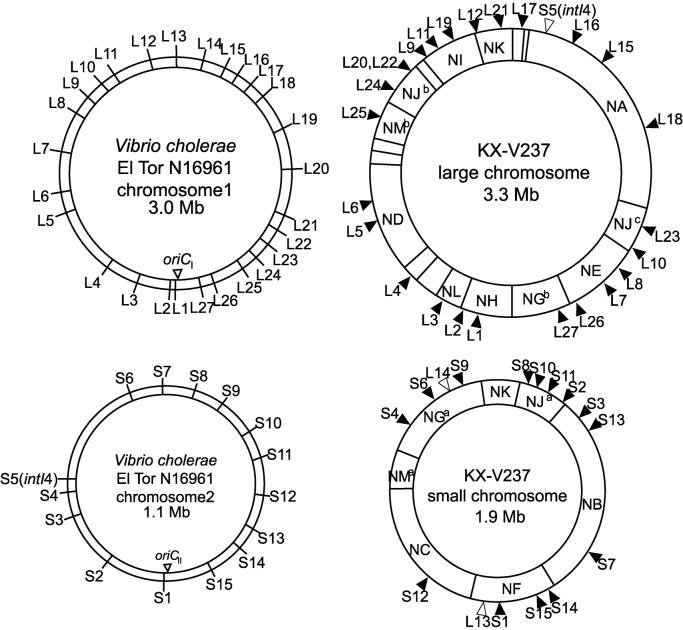

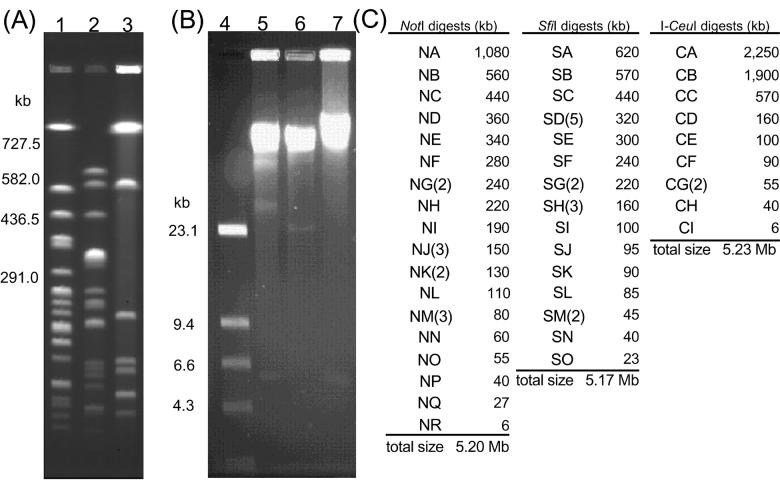

Digestion of the genomic DNA of V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237 with restriction enzymes NotI, SfiI, and I-CeuI yielded 24, 23, and 10 DNA fragments, respectively (Fig. 1). The sums of the sizes of the NotI, SfiI, or I-CeuI fragments were approximately 5.2 Mb in each case (Fig. 1C); thus, the total genome size of KX-V237 was estimated to be approximately 5.2 Mb. We constructed a physical map of this genome by linking the 24 NotI fragments using linking clones prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Table 1 contains a list of the linking clones that we used and the NotI fragments linked by these linking clones. The physical map of the KX-V237 genome which we constructed is shown in Fig. 2. The genome of KX-V237 comprised two separate circular chromosomes, similar to the structure that we reported for V. parahaemolyticus strain AQ4673 (33). The size of the large chromosome was 3.3 Mb, and the size of the small chromosome was 1.9 Mb. These sizes conformed well with those found for the two chromosomes of AQ4673 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 1.

Restriction fragments of the genomic DNA of KX-V237. (A and B) Genomic DNA of KX-V237 was digested with NotI (lanes 1 and 5), SfiI (lanes 2 and 6), or I-CeuI (lanes 3 and 7) and then analyzed by PFGE (A) or FIGE (B). Lane 4 contained λ HindIII molecular weight markers. (C) Size of each restriction fragment.

TABLE 1.

Linking clones used and NotI fragments linked by the linking clones

| NotI fragments linked | NotI-linking clone(s) | SfiI fragment hybridized | I-CeuI fragment hybridized |

|---|---|---|---|

| NI-NJ | #12-10-H | SD | CA |

| NG-NM | P106, T104 | SB | CB |

| ND-NN | E103, S111, #13-6-A | SE | CD |

| NB-NF | E105, #12-6-C | SH | CA |

| NE-NG | E009 | SG | CC |

| NJ-NM | E107, #14-2-E | SD | CB |

| NL-NM | B103 | SE | CG |

| NM-NN | P102 | SE | CG |

| NC-NM | P103, #13-12-B | SB | CB |

| NI-NK | P107 | SD | CA |

| NA-NR | #14-5-A | SA | CA |

| NQ-NR | P109 | SA | CA |

| NH-NL | M104, #13-2-C | SD | CF |

| NK-NQ | S111, #14-4-E | SA | CA |

| NG-NH | P108, #13-3-A | SD | CC |

| NC-NF | T106, #12-5-A | SD | CB |

| NE-NJ | E104 | SD | CA |

| NO-NP | S104, #11-12-B | SD | CA |

| NA-NJ | E101 | SC | CA |

| NB-NJ | S114 | SD | CB |

| NG-NK | T101 | SB | CB |

| NJ-NK | B102 | SD | CB |

| NM-NP | E102 | SD | CA |

| ND-NO | M101 | SD | CA |

FIG. 2.

Physical map of the genome of V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237. The linkage of NotI fragments and the relative locations of SfiI and I-CeuI fragments are shown. In this study, we constructed the map of NotI restriction fragments. The SfiI or I-CeuI fragments are not linked by, for example, linking clones. This is why the arcs that indicate the SfiI or I-CeuI fragments have gaps. The positions of the SfiI or I-CeuI fragments were determined from the results of hybridization with the NotI-linking clones or probes for the genes indicated. The restriction fragments whose designations have a superscript (e.g., SDb) are the fragments for which multiple fragments having indistinguishable sizes were found (Fig. 1); we could not identify which fragment was which.

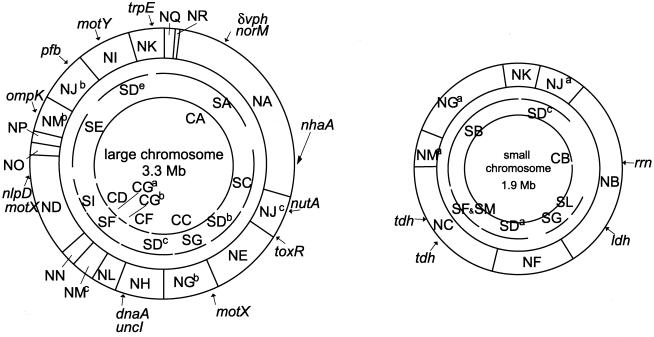

FIG. 3.

Comparison of genetic maps of KX-V237 and AQ4673. The arrows on the large chromosomes indicate a putative genetic inversion between the two strains. Although I-CeuI digestion of the genomic DNA of KX-V237 and AQ4673 suggested the presence of 10 and 9 rrn operons, respectively, fewer rrn operons are indicated because a single NotI fragment can have more than one rrn operon.

Comparison of genetic maps of the chromosomes of KX-V237 and AQ4673.

Localizing the genes of V. parahaemolyticus reported so far by using Southern hybridization, we constructed a genetic map of the KX-V237 chromosomes (Fig. 3). Our results indicate that the small chromosome possesses at least one rrn operon that encodes rRNA. Since digestion of the KX-V237 genome with I-CeuI, which cleaves a specific sequence present only in rrn, yielded 10 DNA fragments (Fig. 1), it is likely that the genome possesses at least 10 rrn operons. Similar analysis with I-CeuI digestion suggested that AQ4673 possesses nine rrn operons (data not shown). Comparing the genetic maps of the large chromosomes of KX-V237 and AQ4673, we found an apparent difference in gene order in the circular chromosome. This difference can be plausibly interpreted as resulting from a genetic inversion event occurring as indicated in Fig. 3. On the small chromosome, both of the copies of the tdh gene, a major virulence factor gene of V. parahaemolyticus, were located on a single NotI fragment, fragment NC (Fig. 3). Compared with the positions of rrn and ldh, the relative position of the tdh gene on the small chromosome of KX-V237 was similar to that of tdh and trh on the small chromosome of AQ4673 (Fig. 3).

Comparison of genetic maps of the chromosomes of KX-V237 and V. cholerae N16961.

To ascertain the differences in the genome structures of two species of Vibrio, the genetic map of the chromosomes of KX-V237 was compared with that of V. cholerae N16961. Since the whole genome sequence of N16961 was available from the Institute for Genomic Research database, we obtained 27 probes (probes L1 to L27) for the ORFs present on chromosome 1 (large chromosome) and 15 probes (probes S1 to S15) for ORFs on chromosome 2 (small chromosome) of N16961, as described in Materials and Methods; the probes are described in Table 2. Positions corresponding to these probes were distributed in almost all the regions of the N16961 genome, as shown in Fig 4 . The locations of homologues for the ORFs on the KX-V237 genome were analyzed by Southern hybridization with the prepared probes. The results are summarized in Fig. 4 and 5. The data revealed that most of the ORFs present on chromosome 1 of N16961 had a homologue on the large chromosome of KX-V237. The findings were similar for ORFs present on the small chromosome. Most of the ORFs present on chromosome 2 of N16961 had a homologue on the small chromosome of KX-V237. These results suggest that the bias of distribution of the ORFs on the large and small chromosomes has been well conserved in the two species. Nevertheless, it is curious that the orders of the locations of the homologous sequences in the chromosomes of the two species have diverged so much (Fig. 5).

TABLE 2.

Probes and ORF of V. cholerae N16961 corresponding to each probe

| Probe | ORF | Description |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | VC0003 | Thiophene and furan oxidation protein ThdF |

| L2 | VC0012 | Chromosomal DNA replication initiator DnaA |

| L3 | VC0134 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| L4 | VC0275 | Phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase PurD |

| L5 | VC0533 | Lipoprotein NlpD |

| L6 | VC0543 | RecA protein |

| L6 | VC0717 | Putative protease |

| L8 | VC0852 | DNA repair protein RecN |

| L9 | VC0984 | Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR |

| L10 | VC1008 | Sodium-type flagellar protein MotY |

| L11 | VC1091 | Oligopeptide ABC transporter, periplasmic oligopeptide-binding protein OppA |

| L12 | VC1174 | Anthranilate synthase component I TrpE |

| L13 | VC1220 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase, beta chain PheT |

| L14 | VC1354 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| L15 | VC1486 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| L16 | VC1540 | Multidrug resistance protein NorM, putative |

| L17 | VC1623 | Carboxynorspermidine decarboxylase NspC |

| L18 | VC1627 | Na+/H+ antiporter protein NhaA |

| L19 | VC1751 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| L20 | VC1903 | Cell division protein FtsK, putative |

| L21 | VC2030 | RNase E Rne |

| L22 | VC2162 | Permease PerM, putative |

| L23 | VC2174 | UDP-sugar hydrolase UshA |

| L24 | VC2290 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, Na translocating, beta subunit NqrF |

| L25 | VC2305 | Outer membrane protein OmpK |

| L26 | VC2431 | Topoisomerase IV, subunit B ParE |

| L27 | VC2560 | Sulfate adenylate transferase, subunit 2 CysD |

| S1 | VCA0011 | Regulatory protein MalT |

| S2 | VCA0103 | Sulfate permease family protein |

| S3 | VCA0204 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase RhlE |

| S4 | VCA0276 | Glycine cleavage system P protein GcvP, authentic frameshift |

| S5 | VCA0291 | Site-specific recombinase IntI4 |

| S6 | VCA0511 | Anaerobic ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase NrdD |

| S7 | VCA0606 | Phosphonoacetaldehyde phosphonohydrolase PhnX |

| S8 | VCA0657 | Aerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GlpD |

| S9 | VCA0702 | Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase |

| S10 | VCA0759 | Arginine ABC transporter, periplasmic arginine-binding protein ArtI |

| S11 | VCA0805 | Exoribonuclease II Rnb |

| S12 | VCA0859 | Oxidoreductase, aldo/keto reductase 2 family |

| S13 | VCA0937 | Transcriptional regulator, AraC/XylS family |

| S14 | VCA0982 | Transcriptional regulator, LysR family |

| S15 | VCA1026 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

FIG. 5.

Comparison of genetic maps of V. cholerae N16961 and V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237. The maps are in a linearized form, starting at the oriC sites of the N16961 genome.

In previous studies (10, 31) workers reported that the rrn genes were present only on the large chromosome of V. cholerae and that no rrn genes were present on the small chromosome. In V. parahaemolyticus AQ4673, however, rrn was found on both the large and small chromosomes (33). In this study, we found that KX-V237 possessed at least 10 rrn operons and that at least one of them was on the small chromosome (Fig. 3). Thus, we suggest that even though V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus belong to the same genus, the presence of rrn on the small chromosome varies.

Heidelberg et al. (10) reported that the superintegron and the gene encoding its integrase (IntI4) (5, 19) were located on the small chromosome in V. cholerae N16961. The presence of a similar superintegron was also demonstrated for V. parahaemolyticus (25). Therefore, we investigated on which chromosome the superintegron was present in KX-V237. The probe which we prepared for intI4 (probe S5) hybridized with the NA fragment of the KX-V237 genome (Fig. 4). We also prepared a probe for VPR, a repeat sequence that constitutes the superintegron of V. parahaemolyticus (25), and analyzed the location of VPR in the KX-V237 genome. The probe hybridized only with the NA fragment (data not shown), thus confirming that the superintegron is located on the NA fragment. These results suggest that the superintegron of V. parahaemolyticus is located on the large chromosome and not on the small chromosome.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we constructed a physical and genetic map of the chromosomes of KX-V237, a KP-positive V. parahaemolyticus strain. KX-V237 was found to possess two circular chromosomes whose sizes were similar to those previously reported for the KP-negative V. parahaemolyticus AQ4673 (Fig. 2 and 3) (33). The relative positions of the genes on the genomes were well conserved in the two strains, but a large inversion on the large chromosomes was suggested (Fig. 3). Taking into consideration the position of dnaA, which is often found near the replication origin of bacterial chromosomes, the observed inverse locations of the genes on the large chromosomes of KX-V237 and AQ4673 are likely to be due to a symmetric chromosomal inversion around the replication origin. Similar symmetric chromosomal inversions in strains belonging to a single species have been reported by several researchers (8, 18, 28); thus, the present data might be another example of such inversions.

It has been suggested that tdh and trh were introduced some time in the past from another bacterium into V. parahaemolyticus (22). Recently, it was reported that the DNA regions surrounding tdh and trh might form a pathogenicity island (9) in the genome of V. parahaemolyticus (14, 15, 23). In this study, the tdh gene, the major virulence factor gene of V. parahaemolyticus, was found on the small chromosome of KX-V237. The relative position of the tdh gene was similar to the position of the tdh and trh genes on the small chromosome of the KP-negative strain AQ4673 (Fig. 3). Although the presence of tdh and trh in V. parahaemolyticus varies depending on the strain (14, 29, 30), the present data suggest that the integrated positions of the putative pathogenicity islands of KP-positive (e.g., KX-V237) and KP-negative (e.g., AQ4673) strains might be the same.

The use of I-CeuI to digest the genomic DNA of KX-V237 and AQ4673 provided evidence that these strains possess 10 and 9 rrn operons, respectively. KX-V237 is one of the strains recently exhibiting pandemic spread across Asia and North America (2-4, 7, 13). Since an increase in the number of rrn operons may give an organism a selective advantage for survival in a continually fluctuating environment (17), the observed increase in the number of rrn operons could be one of the factors responsible for making certain strains of V. parahaemolyticus pandemic.

Recently, the whole genome sequence of another vibrio, V. cholerae N16961, was reported (10). Noting that the N16961 genome also has a two-chromosome structure (10), we compared the genome structures of V. parahaemolyticus KX-V237 and V. cholerae N16961 to elucidate the structural similarities and differences of these organisms. Although the sizes of the large chromosomes of V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae were similar, the sizes of the small chromosomes differed greatly (1.9 Mb in KX-V237 and 1.1 Mb in N16961). At present, it is unclear why the small chromosome of V. parahaemolyticus is 0.8 Mb bigger than that of V. cholerae. The toxin gene of V. parahaemolyticus, tdh, was present in the small chromosome. If the region surrounding the tdh gene does form a pathogenicity island (14, 15, 23), this might be one of the components which makes the small chromosome of V. parahaemolyticus so much bigger than that of V. cholerae. Detailed elucidation of the actual extra DNA sequences of the small chromosome of V. parahaemolyticus is a task for the future.

Comparison of the genetic maps of N16961 and KX-V237 revealed that most of the ORFs present on the large chromosome of V. cholerae had a homologue on the large chromosome of V. parahaemolyticus. We also found that most of the ORFs present on the small chromosome of N16961 had a homologue on the small chromosome of KX-V237. The difference in the orders of the homologues on the chromosomes of N16961 and KX-V237 implies that numerous frequent genetic exchanges have occurred intrachromosomally rather than interchromosomally (Fig. 4 and 5). The observed discrepancy of the frequencies of hypothetical intra- and interchromosomal genetic exchanges can be explained in several ways. It might simply be due to physical distance. Proximity itself may result in recombination events that occur more frequently within chromosomes than between chromosomes. Another interesting possibility is that the discrepancy is due to the differences in the functions of each chromosome. Vibrios, especially those pathogenic for humans, have to adapt to more than one environments to survive under various circumstances, such as in marine or estuarine water, on the surfaces of aquatic flora and fauna, and in human hosts. Heidelberg et al. (10) have proposed that the genes on the large and small chromosomes of V. cholerae function differently depending on the environments encountered by the organisms and that the organisms adapt to different situations by varying the copy number of the chromosomes. Adaptation of vibrios to different environments that is accomplished by regulating the copy number of the large and small chromosomes would explain the observed similarity of the distribution of the homologues on each chromosome. This variation in the copy number of the chromosomes in vibrios, however, has not been experimentally demonstrated yet. Further study is needed to resolve this issue.

Heidelberg et al. (10) have proposed that the small chromosome of V. cholerae was derived from a megaplasmid captured by an ancestral vibrio. Several lines of evidence support this hypothesis. For example, an integron, an element often found on plasmids (19), has been found on the small chromosome of N16961 (10). Evidence from the present study, however, shows that the superintegron occurs on the large chromosome rather than the small chromosome in V. parahaemolyticus. This difference in the location of the superintegron in the same Vibrio species indicates that the chromosomal location of the superintegron cannot be used as evidence to support the megaplasmid hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Kansai International Airport quarantine station for providing the V. parahaemolyticus strains used in this study.

This work was supported by the Research for the Future Programs (grants 97L00101 and 97L00704) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and by an International Health Cooperation Research grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with eating raw oysters—Pacific Northwest, 1997. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:457-462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection associated with eating raw oysters and clams harvested from Long Island Sound—Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, 1998. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:48-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chowdhury, N. R., S. Chakraborty, T. Ramamurthy, M. Nishibuchi, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2000. Molecular evidence of clonal Vibrio parahaemolyticus pandemic strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, C. A., L. Purins, P. Kaewrakon, and P. A. Manning. 1997. VCR repetitive sequence elements in the Vibrio cholerae chromosome constitute a mega-integron. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1137-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colwell, R. R., and A. Huq. 1994. Environmental reservoir of Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 740:44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels, N. A., L. MacKinnon, R. Bishop, S. Altekruse, B. Ray, R. M. Hammond, S. Thompson, S. Wilson, N. H. Bean, P. M. Griffin, and L. Slutsker. 2000. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973-1998. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1661-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisen, J. A., J. F. Heidelberg, O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 2000. Evidence for symmetric chromosomal inversions around the replication origin in bacteria. Genome Biol. Res. 1:0011.1-0011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groisman, E. A., and H. Ochman. 1996. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell 87:791-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, et al. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda, T., and T. Iida. 1993. The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct haemolysin and related haemolysins. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 4:106-113. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honda, T., Y.-X. Ni, and T. Miwatani. 1988. Purification and characterization of a hemolysin produced by a clinical isolate of Kanagawa phenomenon-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related to the thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 56:961-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iida, T., A. Hattori, K. Tagomori, H. Nasu, R. Naim, and T. Honda. 2001. Filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:477-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida, T., K.-S. Park, O. Suthienkul, J. Kozawa, Y. Yamaichi, K. Yamamoto, and T. Honda. 1998. Close proximity of the tdh, trh and ure genes on the chromosome of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microbiology 144:2517-2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iida, T., O. Suthienkul, K.-S. Park, G.-Q. Tang, R. K. Yamamoto, M. Ishibashi, K. Yamamoto, and T. Honda. 1997. Evidence for genetic linkage between the ure and trh genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Med. Microbiol. 46:639-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph, S. W., R. R. Colwell, and J. B. Kaper. 1982. Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related halophilic vibrios. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 10:77-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khetawat, G., R. K. Bhadra, S. Nandi, and J. Das. 1999. Resurgent Vibrio cholerae O139: rearrangement of cholera toxin genetic elements and amplification of rrn operon. Infect. Immun. 67:148-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, S.-L., and K. E. Sanderson. 1996. Highly plastic chromosomal organization in Salmonella typhi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10303-10308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazel, D., B. Dychinco, V. A. Webb, and J. Davies. 1998. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science 280:605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarter, L. 1999. The multiple identities of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:51-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasu, H., T. Iida, T. Sugahara, Y. Yamaichi, K.-S. Park, K. Yokoyama, K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and T. Honda. 2000. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishibuchi, M., and J. B. Kaper. 1995. Thermostable direct hemolysin gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a virulence gene acquired by a marine bacterium. Infect. Immun. 63:2093-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park, K.-S., T. Iida, Y. Yamaichi, T. Oyagi, K. Yamamoto, and T. Honda. 2000. Genetic characterization of DNA region containing the trh and ure genes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect. Immun. 68:5742-5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roszak, D. B., and R. R. Colwell. 1987. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol. Rev. 51:365-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., A.-M. Guetout, P. Ploncard, B. Dychinco, J. Davies, and D. Mazel,. 2001. The evolutionary history of chromosomal super-integrons provides an ancestry for multiresistant integrons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:652-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakazaki, R., K. Tamura, T. Kato, Y. Obara, S. Yamai, and K. Hobo. 1968. Studies on the enteropathogenic, facultatively halophilic bacteria. Vibrio parahaemolyticus. III. Enteropathogenicity. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 21:325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Stibitz, S., and M.-S. Yang. 1997. Genomic fluidity of Bordetella pertussis assessed by a new method for chromosomal mapping. J. Bacteriol. 179:5820-5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suthienkul, O., T. Iida, K.-S. Park, M. Ishibashi, S. Supavej, K. Yamamoto, and T. Honda. 1996. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of the tdh and trh genes in clinical Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1293-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suthienkul, O., M. Ishibashi, T. Iida, N. Nettip, S. Supavej, B. Eampokalap, M. Makino, and T. Honda. 1995. Urease production correlates with possession of the trh gene in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1405-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trucksis, M., J. Michalski, Y. K. Deng, and J. B. Kaper. 1998. The Vibrio cholerae genome contains two unique circular chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14464-14469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wachsmuth, K., Ø. Olsvik, G. M. Evins, and T. Popovic. 1994. Molecular epidemiology of cholera, p. 357-370. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and Ø. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspective. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Yamaichi, Y., T. Iida, K.-S. Park, K. Yamamoto, and T. Honda. 1999. Physical and genetic map of the genome of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: presence of two chromosomes in Vibrio species. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1513-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]