Abstract

Two DNA transfer systems encoded by the tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid have been previously identified in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The virB operon is required for the transfer of transferred DNA to the plant host, and the trb system encodes functions required for the conjugal transfer of the Ti plasmid between cells of Agrobacterium. Recent availability of the genome sequence of Agrobacterium allowed us to identify a third system that is most similar to the VirB type IV secretion system of Bartonella henselae. We have designated this system avhB for Agrobacterium virulence homologue virB. The avhB loci reside on pAtC58 and encode at least 10 proteins (AvhB2 through AvhB11), 7 of which display significant similarity to the corresponding virulence-associated VirB proteins of the Ti plasmid. However, the AvhB system is not required for tumor formation; rather, it mediates the conjugal transfer of the pAtC58 cryptic plasmid between cells of Agrobacterium. This transfer occurs in the absence of the Ti plasmid-encoded VirB and Trb systems. Like the VirB system, AvhB products promote the conjugal transfer of the IncQ plasmid RSF1010, suggesting that these products comprise a mating-pair formation system. The presence of plasmid TiC58 or plasmid RSF1010 reduces the conjugal transfer efficiency of pAtC58 10- or 1,000-fold, respectively. These data suggest that complex substrate interactions exist among the three DNA transfer systems of Agrobacterium.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens causes tumors on a wide variety of plants following the transfer and expression of its transferred DNA (T-DNA) in the plant genome (59). This host range has been extended under laboratory conditions to include yeast, filamentous fungi, and animal cells (9, 10, 16, 28, 40). The unique biological nature of the Agrobacterium-host relationship and its importance in generating transgenic plants have fostered intense interest in understanding the mechanism by which Agrobacterium transfers DNA to its eukaryotic host. The recognition by Agrobacterium of signals produced by wounded plants leads to the induction of a regulon required for the transfer of T-DNA (55). This effect can be reproduced in the laboratory by using induction medium (IM) that mimics the conditions the bacteria encounter during their interaction with the host (11). T-DNA is transferred as a single strand with its 5′ end covalently linked to the VirD2 protein. Recent genetic evidence has shown conclusively that the virulence proteins VirE2 and VirF are exported into plant cells and that this process depends on the type IV secretion apparatus comprised of the VirB1 to VirB11 and VirD4 proteins (50). Although the essential virB operon encodes a pilus (20), termed the T-pilus (29), the notion that the T-pilus is the conduit for the transfer of T-DNA and proteins from the bacterial cytoplasm into host cells in a single step has not been demonstrated. In contrast, recent work in our laboratory suggests a two-step transfer process since the virulence proteins VirE2 and VirF and VirD2 are present in the periplasm of Agrobacterium strains lacking the VirB proteins (12).

Type IV secretion systems are found in plant and animal pathogens as well as in symbiotic bacteria (reviewed in reference 30). These systems are known to transport proteins or nucleoprotein complexes and are commonly associated with virulence. In addition to T-DNA (48), VirE2 and VirF of A. tumefaciens (50), pertussis toxin in Bordetella pertussis (54), and the CagA protein in Helicobacter pylori (39) are native substrates that depend upon type IV secretion systems for their transfer. These proteins are required for virulence in each of these organisms. Although the substrates of other type IV systems have not yet been identified, putative cellular functions for some of these systems have been defined. In Brucella abortus, a type IV secretion system contributes to the intracellular survival of the pathogen in its host environment (38). Bartonella tribocorum contains a recently identified type IV system required for intraerythrocytic bacteremia (43). Legionella pneumophila contains two putative type IV systems, the Lvh system and the Icm/Dot system, of which only the Icm/Dot system is required for the intracellular survival of this pathogen (7, 42).

The proteins comprising type IV secretion systems are ancestrally related to proteins of the mating-pair formation (Mpf) systems required for plasmid conjugal transfer (reviewed in reference 13). Both the Mpf and type IV systems are thought to form a pilus required for substrate transfer to recipient cells, although this structure has only been confirmed in Agrobacterium and Escherichia coli (58). It remains to be determined if other type IV systems, especially those for which components are absent or remain to be identified, comprise a functional pilus. Agrobacterium contains two type IV/Mpf systems encoded by the virB and trb operons of pTiC58. Although both the Trb and VirB systems are encoded in the Ti plasmid, they have different specificities and mediate the transfer of the Ti plasmid or T-DNA, respectively (51). The Trb system consists of 11 proteins, 6 of which are similar in amino acid sequence to the VirB proteins (32), although the genes are not arranged similarly. In addition to their role in T-DNA transfer, VirB products can assist in the transfer of the heterologous plasmid RSF1010, which, while mobilizable, lacks an Mpf system (4, 19). However, under noninducing conditions, a comparable frequency of pRSF1010 transfer was observed if pAtC58 was present (14, 21), suggesting that proteins encoded by this plasmid can also mobilize pRSF1010. Although this was assayed in a strain in which both the Trb system and pAtC58 were present, strains carrying mutations in virB do not conjugally transfer pRSF1010, indicating that the Trb system does not play a role in this process (19).

Conjugal transfer also requires a DNA transfer and replication (Dtr) system that recognizes and cleaves at the origin of transfer (oriT) to facilitate DNA translocation (58). Dtr-like components linked to type IV secretion have been identified in Agrobacterium (18, 57). These include the tra system required for pTiC58 conjugal transfer as well as the products of the virD and virC operons required for T-DNA transfer. Additional Dtr components have recently been identified on the linear chromosome, although their functionality remains to be determined (31, 56). Among these systems, the VirD proteins are most distantly related to classic Dtr systems. The VirD2 protein is required for recognition and cleavage at the 25-bp border sequences that delineate the T-DNA (1, 52). These T-border sequences are similar to the oriT sites of conjugal transfer systems (14). A second Dtr-like component, VirD4, is required for DNA transfer and is thought to couple the Dtr and Mpf systems to enable substrate transfer (23).

Since secretion systems defined as members of the type IV family are known to have distinct roles in conjugal transfer or in the transit of virulence factors to mammalian hosts (30), the precise nomenclature to apply to such systems remains in question. The phylogenetic and functional relationships evident between type IV and certain conjugal transfer systems has led to the suggestion that these groups form a type IV superfamily of proteins involved in both the conjugal transfer between bacteria and the transit of virulence factors between bacteria and their eukaryotic host (32).

Here, we report the discovery and characterization of a new type IV secretion system in Agrobacterium which we designate avhB for Agrobacterium virulence homologue virB. We demonstrate that the AvhB system is required for conjugal transfer of the cryptic plasmid pAtC58 in A. tumefaciens. A second cluster of genes similar to the Dtr systems involved in plasmid conjugation resides on pAtC58, although their function remains to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and growth conditions.

Strains of A. tumefaciens and E. coli, as well as the plasmids and primers used in this study, are described in Table 1. E. coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium, and Agrobacterium cells were grown in MG/L medium, AB minimal medium (AB), or IM (11). The concentrations of antibiotics (per milliliter) used in bacterial cultures were as follows: 100 μg of carbenicillin for both Agrobacterium and E. coli, 50 μg of kanamycin for E. coli and 100 μg for Agrobacterium, and 50 μg of rifampin for Agrobacterium. IM was supplemented with 100 μM acetosyringone.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. tumefaciens C58 | A. tumefaciens carrying nopaline-type Ti plasmid | Lab collection |

| A. tumefaciens A6 | A. tumefaciens carrying octopine-type Ti plasmid | Lab collection |

| A. rhizogenes A4 | A. rhizogenes carrying Ri plasmid | Lab collection |

| A. vitis AG57 | A. vitis with limited host range | Lab collection |

| A348 | C58 cured of pTiC58 and transformed with pTiA6NC | Lab collection |

| A136 | C58 cured of pTiC58 | Lab collection |

| A348ΔvirB2 | A348 deleted of virB2 gene | Lab collection |

| UIA5 | C58 cured of both pTiC58 and pAtC58 | Lab collection |

| NT1TcR1 | C58 cured of pTiC58 and deleted of Tetr | 34 |

| A348(pBISN1) | A348 carrying a β-glucuronidase-intron binary plasmid | This study |

| GV3350 | C58 cured of pTiC58 with Tn1 insertion in pAtC58 | 41 |

| GV3350(pDCP4.4) | GV3350 transformed with pDCP4.4 | This study |

| GV3350(pML122ΔGm) | GV3350 transformed with pML122ΔGm | This study |

| A348ΔavhB | A348 with avhB deletion generated by pYCΔavhB | This study |

| A348ΔavhB(pBISN1) | A348ΔavhB carrying an intron GUS binary plasmid | This study |

| GV3350ΔavhB | GV3350 with avhB deletion generated by pYCΔavhB | This study |

| GV3350ΔavhB(pDCP4.4) | GV3350ΔavhB transformed with pDCP4.4 | This study |

| GV3350ΔavhB(pML122ΔGm) | GV3350ΔavhB transformed with pML122ΔGm | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pYCΔavhB | Construct for deletion of avhB | This study |

| pDCP4.4 | Minimal Ti plasmid with tra region and oriT | 14 |

| pML122ΔGm | pRSF1010-derived plasmid | 20 |

| pBISN1 | Binary vector carrying intron GUS expression construct in T-DNA region | 36 |

| Primers | ||

| AvhB2-5′ | ATGATAATCAGTTCCCGGAT | This study |

| AvhB2-3′ | TCAGGCTCCGACGATGGTGT | This study |

| AvhB11-5′ | ATGTCAGAGAGGCAAGAATC | This study |

| AvhB11-3′ | ATTGTCATGCTGACAGTGTC | This study |

| AstE-5′ | AATCACCAGACTTTTAATCT | This study |

| ΔavhBUp-5′ | AAAGAATTCCAGGCATTTCCGGTCGCTGTG | This study |

| ΔavhBUp-3′ | AAATCTAGACGTTCCACCGGAAGGGATGT | This study |

| ΔavhBDown-5′ | AAATCTAGACATGAGCTCGATTTCACCTA | This study |

| ΔavhBDown-3′ | AAAAAGCTTGTTCCGGTCCTGACGTTCGC | This study |

Construction of deletions by unmarked homologous recombination.

The deletion mutants of avhB in Agrobacterium strains A348 and GV3350 were generated as described by Hoang et al. (24). Plasmid YCΔavhB was used to generate a deletion of the avhB gene cluster (avhB2 to avhB11) in these strains via homologous recombination. To construct this plasmid, PCR was first used to amplify ∼1-kb regions upstream and downstream of the 5′ (primers ΔavhBUp-5′ and ΔavhBUp-3′) and 3′ (primers ΔavhBDown-5′ and ΔavhBDown-3′) ends of the avhB operon. These fragments were digested with primer-specific restriction enzymes (XbaI and EcoRI for the avhB upstream PCR product and XbaI and HindIII for the avhB downstream PCR product) and ligated directionally into pGEX18Gm, resulting in pYCΔavhB. This plasmid was introduced into each of the strains by electroporation, and single recombinants were selected based on resistance to gentamicin and sensitivity to sucrose. Unmarked double recombinants in which the avhB gene cluster was deleted were identified as gentamicin-sensitive and sucrose-resistant colonies and were verified by PCR.

Conjugation assay.

Donor strains used in this study were A. tumefaciens GV3350 (41) and the isogenic strain GV3350ΔavhB in which the avhB operon was deleted. Strain GV3350 is chloramphenicol resistant, lacks pTiC58, and carries a carbenicillin resistance marker on the transposon Tn1 located in pAtC58. The recipient used in this study was the rifampin-resistant A. tumefaciens strain UIA5, which lacks both pTiC58 and pAtC58. Conjugation was performed as described by Cook and Farrand (14). Donor and recipient strains were grown overnight at 28°C in the medium to be used for the conjugation assay (MG/L, AB, or IM) and resuspended at similar cell densities (optical densities at 600 nm). Cells were mixed in a 1/1 ratio, and 100 μl of the mixture was spotted onto nitrocellulose filters and incubated overnight on MG/L, AB, or IM plates. Cells were then serially diluted on medium containing rifampin and carbenicillin to select for transconjugants. Donor cell numbers were determined simultaneously by serial dilution on MG/L supplemented with chloramphenicol. All conjugation assays were performed at least twice in triplicate, and the numbers reported are the averages from a representative experiment. All data in the same table are from experiments performed in parallel.

Plant infection assay.

The virulence assays on Kalanchöe diagremontiana were performed as previously described (12). The plant cell culture infection assays were conducted as previously described (17), except that the plant culture was Ageratum conyzoides (27) and the detection plasmid used to monitor T-DNA transfer was pBISN1 (36).

Sequence analysis.

Sequence analysis was performed by the MegAlign program (DNAstar Inc.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the avhB region of pAtC58 has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF396671.

RESULTS

Plasmid AtC58 encodes all components required for its conjugal transfer.

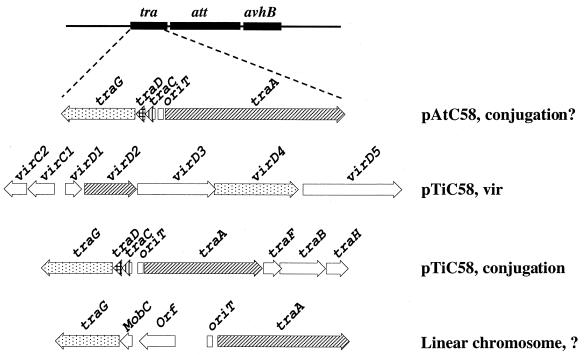

A. tumefaciens C58 has four replicons: one circular chromosome, one linear chromosome, and two plasmids, pAtC58 and the Ti plasmid (2). It has been suggested that pAtC58 is self-transmissible (41); however, none of the three essential components required for plasmid conjugation (Dtr, Mpf, or oriT) have been identified in this plasmid. Recent genome sequence analysis indicates that pAtC58 contains at least two components required for self-transmission (56). These include a putative Dtr system similar to the tra region of the Ti plasmid, including the traA, traC, traD, and traG homologues, and an oriT sequence similar to the oriT of the Ti plasmid (Fig. 1) (18).

FIG. 1.

Known and predicted Dtr systems in A. tumefaciens C58. The spatial relationship between the newly identified Dtr system and the Att and AvhB regions of pAtC58 is shown at the top of the figure. Genes with functional and/or predicted amino acid sequence similarity are shaded similarly. White arrows indicate genes whose predicted protein sequences are not similar.

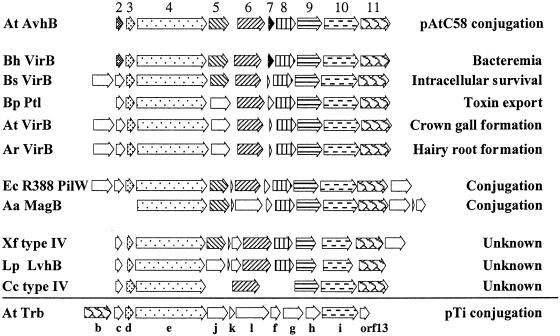

A new type IV secretion system, designated AvhB, was also identified during the genome analysis of pAtC58 (Fig. 2). Since type IV systems have been implicated in both conjugal transfer and virulence, we chose to further characterize this system to determine if it comprised the Mpf system required for pAtC58 transmission. PCR amplification was used to determine if other Agrobacterium strains including A. tumefaciens A6, Agrobacterium rhizogenes A4, or Agrobacterium vitis AG57 contained the AvhB region. None of the above strains yielded a specific band with either the avhB2 or avhB11 primer pairs, suggesting that the avhB loci may be present only in strains derived from C58 (data not shown). These results are consistent with those of previous reports which suggested that pAtC58 is specific to C58-derived strains (49).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the avhB operon with type IV and conjugal transfer Mpf systems. Systems are categorized by function with those most similar in gene order and predicted amino acid sequence to the AvhB system located at the top of each section. Proteins displaying significant similarity to the AvhB proteins are marked with the same pattern as that used for the corresponding AvhB protein. White arrows indicate that an ORF has no homology to the corresponding AvhB proteins. Note that the VirB system of B. henselae is the only system for which all ORFs were similar to AvhB. Aa, A. actinomycetemcomitans; Ar, A. rhizogenes; At, A. tumefaciens; Bh, B. henselae; Bp, B. pertussis; Bs, B. suis; Cc, C. crescentus; Ec, E. coli; Lp, L. pneumophila; Xf, X. fastidiosa.

The att locus, reportedly involved in virulence (35), is located between the avhB2 gene and the traA gene of the putative Dtr system in pAtC58 (Fig. 1). This was surprising, since two reports indicate that pAtC58 is not involved in virulence (26, 41). The basis of this apparent discrepancy is unclear. Conceivably, the att region resides in different locations in different laboratory isolates.

Comparison of the AvhB system with other type IV secretion systems.

The avhB gene cluster contains 10 open reading frames (ORFs), 7 of which are similar to those of the pTiC58 VirB system (Table 2). The arrangement of the genes in these two operons is similar, although the predicted amino acid sequences of AvhB2, AvhB5, and AvhB7 do not share significant similarity with their counterparts in the VirB system (Fig. 2). In addition, no protein in the AvhB system is similar to VirB1 and our analysis of the genome of A. tumefaciens C58 (56) suggests that no VirB1 homologues are present on pAtC58 or elsewhere in the genome. Interestingly, of the 10 type IV systems that share homology with AvhB (Fig. 2), 6 do not contain proteins similar to VirB1 (Actinobacillus, Bartonella, Bordetella, Xylella, Legionella, and Caulobacter). The AvhB cluster has a 200-bp gap between avhB5 and avhB6 that may split the cluster into two operons. A similar arrangement was observed in the pilW system of the E. coli plasmid R388, where trwHGFED and trwLMKJI are presumed to be organized into two transcription units (58). In addition, the avhB region does not appear to have either the vir or tra box sequences in the promoter region, suggesting that the avhB cluster is not directly under the control of plant signal molecules or quorum sensing.

TABLE 2.

Percent identity of each AvhB protein to proteins of other putative type IV secretion systems

| Protein | % Identity to A. tumefaciens AvhB proteina

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | B11 | |

| B. henselae VirB | 36 | 48 | 62 | 17 | 28 | 24 | 49 | 53 | 42 | 58 |

| B. suis VirB | * | 20 | 37 | 20 | 19 | * | 31 | 24 | 27 | 38 |

| B. pertussis Ptl | * | 24 | 31 | * | 15 | * | 25 | 23 | 31 | 36 |

| A. tumefaciens VirB | * | 32 | 37 | * | 20 | * | 21 | 32 | 32 | 33 |

| A. rhizogenes VirB | * | 31 | 14 | * | 19 | * | 19 | 31 | 32 | 33 |

| X. fastidiosa type IV | * | 26 | 43 | 24 | 24 | * | 43 | 29 | 31 | 39 |

| L. pneumophila Lvh | * | 24 | 26 | * | 20 | * | 20 | 20 | 23 | 32 |

| E. coli plasmid R388 PilW | * | 35 | 38 | 20 | 25 | * | 35 | 28 | 31 | 33 |

| C. crescentus type IV | * | 26 | 37 | NA | 18 | NA | NA | 27 | 26 | 36 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans MagB | NA | NA | 33 | 18 | * | NA | 25 | 17 | 29 | 38 |

| A. tumefaciens Trb | NA | 17 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 24 |

Asterisks indicate no similarity when blasted with corresponding AvhB genes. NA indicates no protein in this position. The protein with the highest level of identity with each AvhB protein is underlined.

An analysis of protein similarity and gene organization suggests that the AvhB system is most similar to the VirB system of Bartonella henselae, suggesting that these type IV systems are more closely related than those within Agrobacterium (Fig. 2). The AvhB system resembles other type IV secretion systems including the VirB systems of A. tumefaciens, A. rhizogenes, and Brucella suis; the Lvh system of L. pneumophila (42); the Ptl system of B. pertussis (54); the PilW system of the E. coli plasmid R388 (6); the MagB system of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans plasmid pVT745 (22); and two unnamed type IV-like secretion systems in Caulobacter crescentus (37) and Xylella fastidiosa (44). Overall, AvhB3 and AvhB4 and AvhB8 to AvhB11 are most similar to their respective counterparts in other type IV secretion systems and are generally well conserved among all putative type IV secretion systems. Surprisingly, VirB2 and the 15-kDa proteins of B. henselae are the only proteins in the BLAST database that show any similarity to AvhB2 and AvhB7. The Mpf systems of the F plasmid (tra) and the Ti plasmid (trb) are only distantly related to avhB, based on a comparison of protein similarity and gene organization (Table 2 and data not shown).

The AvhB system is responsible for the conjugal transfer of pAtC58.

Because type IV secretion systems are evolutionarily related to Mpf systems associated with bacterial plasmid conjugal transfer, we asked whether the AvhB system was involved in the conjugal transfer of pAtC58. To prevent either the VirB or the Trb system from interfering with or complementing any AvhB system functions, we used a C58 derivative lacking the Ti plasmid (GV3350) as the donor strain (41). The pAtC58 plasmid in GV3350 was engineered to carry a carbenicillin resistance marker which allowed the convenient selection of pAtC58 transconjugants. UIA5, a rifampin-resistant C58 derivative lacking both pAtC58 and pTiC58, was employed as the recipient strain in all conjugation assays (3).

The conjugation frequency of pAtC58 with the GV3350 donor in MG/L was 10−3, compared with less than 10−8 when GV3350ΔavhB was used as the donor (Table 3). Similar conjugation experiments were also performed in two minimal media, AB and IM. While the transfer frequency of pAtC58 in MG/L and AB was similar, the frequency of transfer in IM was reduced 100-fold. In all cases, the deletion of avhB resulted in an almost complete loss of transfer of pAtC58. We conclude that the AvhB system is required for the conjugal transfer of pAtC58 in A. tumefaciens and that either it or its cognate Dtr system is not expressed or nonfunctional under inducing conditions. Because GV3350 does not contain the Ti plasmid, the AvhB system functions independently of the VirB and the Trb systems in pAtC58 conjugation.

TABLE 3.

Conjugation of pAtC58 by various donor strains

| Donor strain (medium)a | No. of transconjugants (per μl) | Frequency (per input donor) |

|---|---|---|

| GV3350 (MG/L) | 90,000 | 1.9 × 10−3 |

| GV3350 (AB) | 44,233 | 1.8 × 10−3 |

| GV3350 (IM) | 925 | 2.2 × 10−5 |

| GV3350ΔavhB (MG/L, AB, IM) | <1 | <1.3 × 10−8b |

| GV3350(pDCP4.4) (MG/L) | 7,500 | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| GV3350(pML122ΔGm) (MG/L) | 150 | 3.3 × 10−6 |

Experiments were performed in triplicate with six subsamples. Averages of the subsamples from a representative experiment are shown.

The conjugation rates of pAtC58 by the GV3350ΔavhB donor were lower than 10−8 in all conditions assayed.

AvhB promotes the transfer of pRSF1010 but not pTiC58.

In addition to transferring T-DNA, the VirB system is also capable of transferring the IncQ plasmid pRSF1010 into eukaryotic and bacterial cells under vir gene-inducing conditions (8, 20). It has been reported that pAtC58 can complement mutations in many trb and tra genes and partially restore pTiC58 conjugation (33) as well as mediate the transfer of pRSF1010 between agrobacteria under noninducing conditions (14). Since the AvhB system promotes conjugal transfer of pAtC58, it seemed likely that it could also function in the transfer of other plasmids, such as pRSF1010 or pTiC58. To test this possibility, the pRSF1010-derived plasmid pML122ΔGm (20) and a mini plasmid containing the Dtr system (tra) and oriT regions of pTiC58, pDCP4.4 (14), were introduced individually into GV3350 and GV3350ΔavhB, and their transfer was assayed. Both pDCP4.4 and pML122ΔGm carry kanamycin resistance markers and require an Mpf system for conjugal transfer. The transfer frequency of the mini-Ti plasmid, pDCP4.4, was comparable in GV3350 and GV3350ΔavhB (∼1 × 10−8), indicating that the AvhB system alone cannot transfer the Ti plasmid. The pRSF1010 derivative pML122ΔGm, however, was transferred at a 20-fold-higher frequency in GV3350 (1.4 × 10−6) than in GV3350ΔavhB (7.4 × 10−8), indicating that the AvhB system can independently transfer pRSF1010. Similar transfer frequencies were seen for both plasmids in IM (data not shown). These results are consistent with the previous observation that pAtC58 promotes conjugal transfer of pRSF1010 under conditions that do not induce vir genes (14) and show that the AvhB system is required for this transfer.

Both pRSF1010 and pTiC58 inhibit conjugal transfer of pAtC58.

Plasmid RSF1010 reduces T-DNA transfer (5), presumably because it competes with transferred substrates at the transport pore (47). We compared the conjugation frequencies of pAtC58 in GV3350 containing pDCP4.4 or pML122ΔGm to determine if pAtC58 conjugation was also inhibited by pRSF1010 or pTiC58. The presence of pDCP4.4 and pML122ΔGm reduced the conjugation frequency of pAtC58 by ∼10- and ∼1,000-fold, respectively (Table 3). Surprisingly, although the avhB system does not promote efficient conjugal transfer of the pTi substrate (Table 4), this substrate competitively inhibits pAtC58 conjugal transfer.

TABLE 4.

AvhB promotes conjugation of pRSF1010 but not pTiC58

| Donor strain (medium) | pDCP4.4

|

pML122ΔGm

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of transconjugants (per μl) | Frequency (per input donor) | No. of transconjugants (per μl) | Frequency (per input donor) | |

| GV3350 (MG/L, IM) | 1 | 2.1 × 10−8 | 65 | 1.4 × 10−6 |

| GV3350ΔavhB (MG/L, IM) | 0.68 | 1.5 × 10−8 | 3.4 | 7.4 × 10−8 |

The AvhB system is not involved in tumor formation.

Although pAtC58 does not restore tumorigenesis in virB mutants (45), we chose to confirm that the AvhB cluster does not play a role in tumor formation. To investigate this possibility, we generated a deletion of the avhB region in the tumorigenic strain A348 (A348ΔavhB). This mutant grows at a rate indistinguishable from that of its parental strain in MG/L, AB, and IM. K. diagremontiana infection assays were performed with strains A348 and A348ΔavhB. Two weeks after inoculation, both strains induced tumors on all plants inoculated (12 of 12 tested) and the tumors were similar in size (data not shown). In order to detect any minor changes in the transformation efficiency affected by the AvhB deletion, we performed a quantitative infection assay using an A. conyzoides cell culture as the T-DNA recipient (27). The frequencies of β-transient expression from A348(pBISN1) and A348ΔavhB(pBISN1) were similar [17% for A348(pBISN1) and 16% for A348ΔavhB(pBISN1)]. These results confirm that no proteins in the AvhB system are required for effective tumor formation.

DISCUSSION

The observations in this report establish A. tumefaciens C58 as the first bacterium that contains three DNA delivery systems for which each native substrate has been identified. The two previously characterized systems are the VirB system, a type IV secretion system involved in T-DNA transfer to eukaryotic cells (53), and the Trb system, which is required for the conjugal transfer of the Ti plasmid to other bacteria (32). In this report, we have identified and characterized a third type IV secretion system in Agrobacterium, the AvhB system, which resembles the VirB system at both the protein and gene organization levels. This system functions as an Mpf system to conjugally transfer pAtC58 to other cells of Agrobacterium. Our sequence analysis revealed that pAtC58 contains two additional elements required for self-transmissibility, a putative Dtr system for processing the DNA and an oriT-like sequence (Fig. 1). This report provides the first experimental evidence that pAtC58 is a self-transmissible plasmid.

Although the three DNA transfer systems in A. tumefaciens are similar, they do not appear to have redundant functions. All three systems function independently to promote the transfer of their respective DNA substrates. The VirB system was essential for virulence in an Agrobacterium strain in which both the Trb and AvhB systems were functional (46). Our results confirm that the VirB system functions independently of the avhB genes in tumor formation because deletion of the entire avhB cluster had no obvious effect on virulence. A previous investigation using a reconstituted Ti plasmid conjugation system determined that the VirB and AvhB systems are not required in Ti plasmid conjugation (15). In this report, we demonstrate that products of the avhB cluster are required for the conjugal transfer of pAtC58 between agrobacteria. By using a strain cured of its Ti plasmid, we show that conjugation of pAtC58 is independent of the two other DNA delivery systems, VirB and Trb.

Although the three DNA transfer systems have distinct functions, each system transfers noncognate substrates. For example, the Trb system mobilizes pRP4 variants (23) while both the VirB and AvhB systems can transfer the heterologous plasmid pRSF1010 between agrobacteria (Table 4) (20). In addition, the VirB system can mobilize pRSF1010 into plant cells (8). Transfer of pRSF1010 by VirB occurs only under vir gene-inducing conditions that allow expression of the virB operon. In contrast, pRSF1010 mobilization by the AvhB system occurs under both inducing and noninducing conditions as well as in the absence of the Ti plasmid. However, the AvhB system transfers pAtC58 poorly under conditions that activate vir gene expression while pRSF1010 transfer is similar under both conditions (Tables 3 and 4). The reason for this distinction is not clear.

Interestingly, some components among the three DNA transfer systems seem interchangeable. Components of pAtC58 can function in place of the trb gene products, with the exception of TrbI and TrbJ (33). This suggests that a chimeric Mpf system can form between components of the AtC58 plasmid and the Trb system of the Ti plasmid. Since the AvhB system can serve as the Mpf system for both pRSF1010 and pAtC58 and some proteins in AvhB share homology with the Trb system, it seems likely that the AvhB system might contribute the factors that complemented the Trb deletions in the previous report (33). In addition, heterologous substrates transferred by these systems appear to compete for access to the export apparatus. Previous reports suggest that pRSF1010 inhibits tumor formation through substrate competition with both VirE2 and T-DNA (5). In this study, we found that both pRSF1010 and pTiC58 inhibit conjugal transfer of pAtC58 (Table 3), suggesting an overlap between these delivery systems.

Since each of the type IV systems in A. tumefaciens is differentially regulated, it seems likely that they operate in distinct environments. T-DNA transfer resulting in tumor formation requires coordinated activation of the vir genes, which occurs only in the presence of a wounded plant host. Conjugation of the Ti plasmid is mediated by opines produced in plant tumors formed by the transfer, integration, and expression of genes in T-DNA (25, 51). This transfer likely enhances the competitive ability of Agrobacterium strains in this environment, since the ability to degrade tumor-specific opines is encoded by the Ti plasmid. Finally, in this report, we show that the transfer of pAtC58 is most efficient under noninducing conditions. This suggests that pAtC58 mobilization occurs predominantly under soil or rhizosphere conditions in the absence of tumors or plant wound sites, suggesting that this plasmid may play a key role in these environments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Farrand for providing the NT1TcR1 library and the pDCP4.4 plasmid, H. Kanzaki for the A. conyzoides culture, Stan Gelvin for pBISN1, Joao Setubal for preliminary phylogenetic analyses of the avhB cluster and related systems, and Stephen Farrand and Beth Traxler for helpful discussions. We also thank Emily Li for technical assistance and members of the Nester lab for many discussions.

The work was supported by NIH grant GM32618, NIH doctoral fellowship GM19642, NSF grant MCB92815, and a grant from the DuPont Corporation.

L.C. and Y.C. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright, L. M., M. F. Yanofsky, B. Leroux, D. Q. Ma, and E. W. Nester. 1987. Processing of the T-DNA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens generates border nicks and linear, single-stranded T-DNA. J. Bacteriol. 169:1046-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allardet-Servent, A., S. Michaux-Charachon, E. Jumas-Bilak, L. Karayan, and M. Ramuz. 1993. Presence of one linear and one circular chromosome in the Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 genome. J. Bacteriol. 175:7869-7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alt-Morbe, J., J. L. Stryker, C. Fuqua, P. L. Li, S. K. Farrand, and S. C. Winans. 1996. The conjugal transfer system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens octopine-type Ti plasmids is closely related to the transfer system of an IncP plasmid and distantly related to Ti plasmid vir genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:4248-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beijersbergen, A., A. den Dulk-Ras, R. A. Schilperoort, and P. J. Hooykaas. 1992. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science 256:1324-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binns, A. N., C. E. Beaupre, and E. M. Dale. 1995. Inhibition of VirB-mediated transfer of diverse substrates from Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the IncQ plasmid RSF1010. J. Bacteriol. 177:4890-4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolland, S., M. Llosa, P. Avila, and F. de la Cruz. 1990. General organization of the conjugal transfer genes of the IncW plasmid R388 and interactions between R388 and IncN and IncP plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 172:5795-5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brand, B. C., A. B. Sadosky, and H. A. Shuman. 1994. The Legionella pneumophila icm locus: a set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 14:797-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan-Wollaston, V., J. E. Passiatore, and F. Cannon. 1987. The mob and oriT mobilization functions of a bacterial plasmid promote its transfer to plants. Nature 328:172-175. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bundock, P., A. den Dulk-Ras, A. Beijersbergen, and P. J. Hooykaas. 1995. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14:3206-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bundock, P., K. Mroczek, A. A. Winkler, H. Y. Steensma, and P. J. Hooykaas. 1999. T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens as an efficient tool for gene targeting in Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cangelosi, G. A., E. A. Best, G. Martinetti, and E. W. Nester. 1991. Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium. Methods Enzymol. 204:384-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, L., C. M. Li, and E. W. Nester. 2000. Transferred DNA (T-DNA)-associated proteins of Agrobacterium tumefaciens are exported independently of virB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7545-7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christie, P. J. 2001. Type IV secretion: intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol. Microbiol. 40:294-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook, D. M., and S. K. Farrand. 1992. The oriT region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid pTiC58 shares DNA sequence identity with the transfer origins of RSF1010 and RK2/RP4 and with T-region borders. J. Bacteriol. 174:6238-6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook, D. M., P.-L. Li, F. Ruchaud, S. Padden, and S. K. Farrand. 1997. Ti plasmid conjugation is independent of vir: reconstitution of the tra functions from pTiC58 as a binary system. J. Bacteriol. 179:1291-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Groot, M. J., P. Bundock, P. J. Hooykaas, and A. G. Beijersbergen. 1998. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:839-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, W., L. Chen, D. W. Wood, T. Metcalfe, X. Liang, M. P. Gordon, L. Comai, and E. W. Nester. 1998. Agrobacterium VirD2 protein interacts with plant host cyclophilins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7040-7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrand, S. K., I. Hwang, and D. M. Cook. 1996. The tra region of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid is a chimera with elements related to the transfer systems of RSF1010, RP4, and F. J. Bacteriol. 178:4233-4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fullner, K. J. 1998. Role of Agrobacterium virB genes in transfer of T complexes and RSF1010. J. Bacteriol. 180:430-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fullner, K. J., J. C. Lara, and E. W. Nester. 1996. Pilus assembly by Agrobacterium T-DNA transfer genes. Science 273:1107-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fullner, K. J., and E. W. Nester. 1996. Temperature affects the T-DNA transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 178:1498-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli, D. M., J. Chen, K. F. Novak, and D. J. Leblanc. 2001. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of conjugative plasmid pVT745. J. Bacteriol. 183:1585-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton, C. M., H. Lee, P. L. Li, D. M. Cook, K. R. Piper, S. B. von Bodman, E. Lanka, W. Ream, and S. K. Farrand. 2000. TraG from RP4 and TraG and VirD4 from Ti plasmids confer relaxosome specificity to the conjugal transfer system of pTiC58. J. Bacteriol. 182:1541-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang, I., D. M. Cook, and S. K. Farrand. 1995. A new regulatory element modulates homoserine lactone-mediated autoinduction of Ti plasmid conjugal transfer. J. Bacteriol. 177:449-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hynes, M. F., R. Simon, and A. Puhler. 1985. The development of plasmid-free strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by using incompatibility with a Rhizobium meliloti plasmid to eliminate pAtC58. Plasmid 13:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanzaki, H., T. Kagemori, S. Asano, and K. Kawazu. 1998. Improved bioassay method for plant transformation inhibitors. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:2328-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunik, T., T. Tzfira, Y. Kapulnik, Y. Gafni, C. Dingwall, and V. Citovsky. 2001. Genetic transformation of HeLa cells by Agrobacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1871-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai, E. M., and C. I. Kado. 1998. Processed VirB2 is the major subunit of the promiscuous pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 180:2711-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai, E. M., and C. I. Kado. 2000. The T-pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Trends Microbiol. 8:361-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leloup, L., E. M. Lai, and C. I. Kado. 2002. Identification of a chromosomal tra-like region in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, P.-L., D. M. Everhart, and S. K. Farrand. 1998. Genetic and sequence analysis of the pTiC58 trb locus, encoding a mating-pair formation system related to members of the type IV secretion family. J. Bacteriol. 180:6164-6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, P.-L., I. Hwang, H. Miyagi, H. True, and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Essential components of the Ti plasmid trb system, a type IV macromolecular transporter. J. Bacteriol. 181:5033-5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo, Z. Q., and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a tetracycline resistance determinant present in Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. J. Bacteriol. 181:618-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthysse, A. G., H. Yarnall, S. B. Boles, and S. McMahan. 2000. A region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens chromosome containing genes required for virulence and attachment to host cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1490:208-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narasimhulu, S. B., X. B. Deng, R. Sarria, and S. B. Gelvin. 1996. Early transcription of Agrobacterium T-DNA genes in tobacco and maize. Plant Cell 8:873-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nierman, W. C., T. V. Feldblyum, M. T. Laub, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, J. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, M. R. Alley, N. Ohta, J. R. Maddock, I. Potocka, W. C. Nelson, A. Newton, C. Stephens, N. D. Phadke, B. Ely, R. T. DeBoy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, J. F. Kolonay, J. Smit, M. B. Craven, H. Khouri, J. Shetty, K. Berry, T. Utterback, K. Tran, A. Wolf, J. Vamathevan, M. Ermolaeva, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, J. C. Venter, L. Shapiro, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4136-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Callaghan, D., C. Cazevieille, A. Allardet-Servent, M. L. Boschiroli, G. Bourg, V. Foulongne, P. Frutos, Y. Kulakov, and M. Ramuz. 1999. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1210-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odenbreit, S., J. Puls, B. Sedlmaier, E. Gerland, W. Fischer, and R. Haas. 2000. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science 287:1497-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piers, K. L., J. D. Heath, X. Liang, K. M. Stephens, and E. W. Nester. 1996. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1613-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg, C., and T. Huguet. 1984. The pAtC58 plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is not essential for tumour induction. Mol. Gen. Genet. 196:533-536. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segal, G., J. J. Russo, and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Relationships between a new type IV secretion system and the icm/dot virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 34:799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seubert, A., R. Schulein, and C. Dehio. 2002. Bacterial persistence within erythrocytes: a unique pathogenicity strategy of Bartonella spp. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:555-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson, A. J., F. C. Reinach, P. Arruda, F. A. Abreu, M. Acencio, R. Alvarenga, L. M. Alves, J. E. Araya, G. S. Baia, C. S. Baptista, M. H. Barros, E. D. Bonaccorsi, S. Bordin, J. M. Bove, M. R. Briones, M. R. Bueno, A. A. Camargo, L. E. Camargo, D. M. Carraro, H. Carrer, N. B. Colauto, C. Colombo, F. F. Costa, M. C. Costa, C. M. Costa-Neto, L. L. Coutinho, M. Cristofani, E. Dias-Neto, C. Docena, H. El-Dorry, A. P. Facincani, A. J. Ferreira, V. C. Ferreira, J. A. Ferro, J. S. Fraga, S. C. Franca, M. C. Franco, M. Frohme, L. R. Furlan, M. Garnier, G. H. Goldman, M. H. Goldman, S. L. Gomes, A. Gruber, P. L. Ho, J. D. Hoheisel, M. L. Junqueira, E. L. Kemper, J. P. Kitajima, J. E. Krieger, M. A. Kuramae, F. Laigret, M. R. Lambais, and L. C. Madeira. 2000. The genome sequence of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Nature 406:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stachel, S. E., and E. W. Nester. 1986. The genetic and transcriptional organization of the vir region of the A6 Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. EMBO J. 5:1445-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stachel, S. E., and P. C. Zambryski. 1986. Agrobacterium tumefaciens and the susceptible plant cell: a novel adaptation of extracellular recognition and DNA conjugation. Cell 47:155-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stahl, L. E., A. Jacobs, and A. N. Binns. 1998. The conjugal intermediate of plasmid RSF1010 inhibits Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence and VirB-dependent export of VirE2. J. Bacteriol. 180:3933-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomashow, M. F., R. Nutter, A. L. Montoya, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1980. Integration and organization of Ti plasmid sequences in crown gall tumors. Cell 19:729-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Montagu, M., and J. Schell. 1979. The plasmids of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, p. 71-95. In A. P. K. N. Timmis (ed.), Plasmids of medical, environmental and commercial importance. Elsevier Science Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 50.Vergunst, A. C., B. Schrammeijer, A. den Dulk-Ras, C. M. de Vlaam, T. J. Regensburg-Tuink, and P. J. Hooykaas. 2000. VirB/D4-dependent protein translocation from Agrobacterium into plant cells. Science 290:979-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Bodman, S. B., J. E. McCutchan, and S. K. Farrand. 1989. Characterization of conjugal transfer functions of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid pTiC58. J. Bacteriol. 171:5281-5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, K., L. Herrera-Estrella, M. Van Montagu, and P. Zambryski. 1984. Right 25 bp terminus sequence of the nopaline T-DNA is essential for and determines direction of DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to the plant genome. Cell 38:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward, J. E., D. E. Akiyoshi, D. Regier, A. Datta, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1988. Characterization of the virB operon from an Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid. J. Biol. Chem. 263:5804-5814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss, A. A., F. D. Johnson, and D. L. Burns. 1993. Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:2970-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winans, S. C. 1991. An Agrobacterium two-component regulatory system for the detection of chemicals released from plant wounds. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2345-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood, D. W., J. C. Setubal, R. Kaul, D. E. Monks, J. P. Kitajima, V. K. Okura, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, G. E. Wood, N. F. Almeida, Jr., L. Woo, Y. Chen, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, P. D. Karp, D. Bovee, Sr., P. Chapman, J. Clendenning, G. Deatherage, W. Gillet, C. Grant, T. Kutyavin, R. Levy, M. J. Li, E. McClelland, A. Palmieri, C. Raymond, G. Rouse, C. Saenphimmachak, Z. Wu, P. Romero, D. Gordon, S. Zhang, H. Yoo, Y. Tao, P. Biddle, M. Jung, W. Krespan, M. Perry, B. Gordon-Kamm, L. Liao, S. Kim, C. Hendrick, Z. Y. Zhao, M. Dolan, F. Chumley, S. V. Tingey, J. F. Tomb, M. P. Gordon, M. V. Olson, and E. W. Nester. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yanofsky, M. F., S. G. Porter, C. Young, L. M. Albright, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1986. The virD operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens encodes a site-specific endonuclease. Cell 47:471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zechner, E. L., F. de la Cruz, R. Eisenbrandt, A. M. Grahn, G. Koraimann, E. Lanka, G. Muth, W. Pansegrau, C. M. Thomas, B. M. Wilkins, and M. Zatyka. 2001. Conjugative-DNA transfer processes, p. 87-174. In C. M. Thomas (ed.), The horizontal gene pool: bacterial plasmids and gene spread. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 59.Zupan, J., T. R. Muth, O. Draper, and P. Zambryski. 2000. The transfer of DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens into plants: a feast of fundamental insights. Plant J. 23:11-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]