Abstract

The partition operon of P1 plasmid encodes two proteins, ParA and ParB, required for the faithful segregation of plasmid copies to daughter cells. The operon is followed by a centromere analog, parS, at which ParB binds. ParA, a weak ATPase, represses the par promoter most effectively in its ADP-bound form. ParB can recruit ParA to parS, stimulate its ATPase, and significantly stimulate the repression. We report here that parS also participates in the regulation of expression of the par genes. A single chromosomal parS was shown to augment repression of several copies of the par promoter by severalfold. The repression increase was sensitive to the levels of ParA and ParB and to their ratio. The increase may be attributable to a conformational change in ParA mediated by the parS-ParB complex, possibly acting catalytically. We also observed an in cis effect of parS which enhanced expression of parB, presumably due to a selective modulation of the mRNA level. Although ParB had been earlier found to spread into and silence genes flanking parS, silencing of the par operon by ParB spreading was not significant. Based upon analogies between partitioning and septum placement, we speculate that the regulatory switch controlled by the parS-ParB complex might be essential for partitioning itself.

Like many plasmids and chromosomes present in low copy numbers, plasmid prophage P1 is rarely lost at cell division. Its remarkable segregational stability is achieved by the mediation of partition proteins encoded by an operon of two genes. They act in conjunction with a cis-acting cluster of sites, parS, referred to as the plasmid centromere. Like many prokaryotic operons, the partition operon of P1 is regulated in a cooperative fashion by the proteins it encodes. The first protein of the operon, ParA, acts as repressor; the second, ParB, acts as corepressor (18).

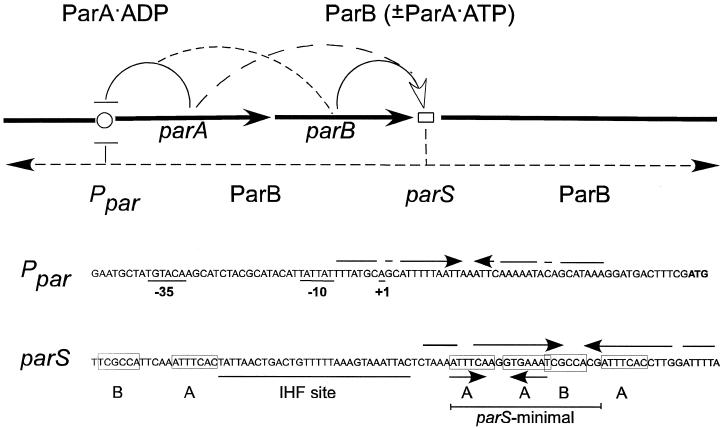

ParA binds in vitro to a region of 80 to 150 bp centered on a 20-bp imperfect palindrome overlapping the promoter, Ppar (9, 11, 29) (Fig. 1). Although the transcription of both parA and parB appears to be initiated principally at Ppar, evidence for a minor parB transcription initiated within parA has also been noted (18). At the opposite end of the operon from Ppar are a set of sites, parS, to which ParB binds (10, 19). Termination of the par transcripts is probably mediated by the large inverted repeat in parS (based on predictions determined using the Terminator program of the Genetics Computer Group). The parS region covers about 94 bp (Fig. 1). Both proteins bind to their respective DNA sites as dimers (9, 20).

FIG. 1.

Regulatory and structural features of the P1 partition operon. Arcs between straight solid arrows representing genes and the symbols for Ppar and for parS indicate that the corresponding proteins can bind to the indicated sites. The dashed arc from parB indicates that ParB can assist the binding of ParA (preferentially in the ADP form) to Ppar; the dashed arc from parA indicates that ParA (in the ATP form) can bind to the ParB-parS complex. The dashed arrows to the right and left of parS in the circuit diagram indicate the capacity of ParB to spread bidirectionally from a nucleation site within parS. The boxed heptamers (A) and hexamers (B) in the parS sequence are ParB binding sites.

ParA exhibits a weak ATPase which is essential for its partition function (11, 13). The binding of ParA to Ppar is promoted by ADP or nonhydrolyzable ATP analogs more effectively than by ATP, but the ATPase activity of ParA inhibits its binding to Ppar in the absence of ParB (5, 9, 11, 13). ParB, although it stimulates the ATPase, promotes the binding of ParA to Ppar. The ParB-mediated promotion of binding depends uniquely on ATP; ADP or nonhydrolyzable ATP analogs cannot serve as replacements (8). It is unlikely that the stimulatory effect of ParB on the binding of ParA to Ppar is due to the production of ADP. Rather, ParB appears to prevent ParA from assuming a conformation that ATP hydrolysis would otherwise favor and that is inappropriate for binding to Ppar (8).

ParB binding to parS is promoted by the host architectural protein IHF (integration host factor), which stabilizes the ParB-parS complex (12, 20, 21). By bending the DNA, IHF most likely allows ParB to contact recognition sites on both sides of the bend simultaneously (22, 27) (Fig. 1). These recognition sites are of two kinds, designated A and B (23, 27, 28). A minimal version of parS (parSmin), which consists of a B box and a palindrome of A boxes (Fig. 1), can function in directing the segregation of plasmids to daughter cells, albeit less efficiently than intact parS (42).

Although in vitro footprints of ParB on DNA that bears a parS locus suggest that ParB binding does not extend much beyond the confines of parS, evidence from in vivo experiments suggests otherwise. The initial evidence for ParB spreading beyond parS was the finding that ParB can silence the expression of flanking genes (51). Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that under physiological conditions ParB can spread for several kilobases into adjacent regions (Fig. 1). Spreading can be halted by interposition of a tightly bound DNA-protein complex in the path of the ParB protein extension. One interpretation of these results is that parS can initiate the formation of a nucleoprotein filament that renders the included DNA inaccessible to RNA polymerase (51). An alternative interpretation, based on studies of the interaction of the ParB-related SopB protein of F with the F parS analog, is that the DNA site at which the partition protein binds and adjacent DNA are sequestered at sites on the cell membrane to which the partition protein independently binds (26, 36, 37, 40; reviewed in reference 58).

ParA does not bind directly to parS nor does ParB bind directly to Ppar, but the two proteins can interact in ways which imply that the two DNA loci communicate with each other. ATP has a central role in this communication (5). An in vitro binding of ParA to the parS-ParB partition complex has been demonstrated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Recruitment of ParA to the parS-ParB complex occurred at high concentrations of ParB, perhaps only when it had acquired at least two ParB dimers. At low ParB concentrations, ParA disassembled ParB from the complex (5). Evidence from the study of a ParA partition mutant (encoding ParAM314I) suggested that ParA can bind to the parS-ParB complex in vivo, in this case more stably than is consistent with active partitioning (60). Formation of a complex of both R1-encoded partition proteins (ParM and ParR) at the partition site (parC) has been suggested (34). The ATPase activity of ParM was activated slightly by ParR and to a much greater extent by the ParR-parC complex. This case is of particular interest, because the proteins themselves appear to have little in common with the more closely related partition proteins of P1 and F (4).

The foregoing findings raise the possibility that independently of its role in nucleating ParB spreading, parS contributes to the transcriptional regulation of the P1 partition operon. The likelihood of such a contribution was reinforced with the finding that the F centromere can contribute in trans to regulation of the F partition operon (59). Furthermore, a study of how an ATP-ADP switch controls ParA activities alludes to an unpublished finding that plasmids containing parS lower the level of Par proteins whose genes are transcribed from Ppar (cited in reference 5). Recognition that parS can strongly influence par operon expression independently of its role in gene silencing by promoting the spreading of ParB came to us by two serendipitous observations that are described below and that motivated the present effort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture methods.

The list of strains used appears in Table 1. Escherichia coli K-12 strain MC1061, our BR6545 [hsdR mcrB araD139 Δ(araABC-leu)7679 ΔlacX74 galU galK rpsL thi] (6), was used throughout, except that E. coli K-12 strain BW23473, our BR8289 [Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 rph-1 rpoS396(Am) robA1 creC510 hsdR514 ΔendA9 uidA(ΔMluI)::pir(wt) endA recA1], was used for maintaining the conditional-replication integration plasmid pAH144 (25). Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium (45) or on LB agar plates at 37°C. Antibiotics were added as follows: ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 20 μg/ml; kanamycin (Km), 25 μg/ml; spectinomycin (Sp), 40 μg/ml; and tetracycline (Tc), 15 μg/ml. For selecting integrants, antibiotics were added at the following lower concentrations: ampicillin, 30 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml; and spectinomycin, 20 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains (MC1061 derivatives) | ||

| BR6902 | recA56 attλ::(PrepA-lacZ cat); construct “0” of reference | 51 |

| BR6903 | recA56 attλ::(parS {rrnB T1}4PrepA-lacZ cat); Construct “1” | 51 |

| BR7313 | attHK022::(Ppar-lacZ; Spr) | This study |

| BR7315 | attHK022::(parS {+}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7317 | attHK022::(parS {−}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7319 | attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7321 | attλ::(bla Ppar-parA parB) attHK022::(parS {+}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7323 | attλ::(bla Ppar-parA parB) attHK022::(parS {−}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7325 | attλ::(bla Ppar-parA parB) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7327 | attλ::(bla Ppar-parA parBparS) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7330 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB) attHK022::(parS {+}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7331 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB) attHK022::(parS {−}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7332 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7333 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB parS) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7369 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7370 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB parS) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7371 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::(parS {−}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7372 | attλ::(Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::(parS {+}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7377 | attλ::cat attHK022::(lacIq Ptac-parA Ptrp-parB) | This study |

| BR7378 | attλ::(parS cat) attHK022::(lacIq Ptac-parA Ptrp-parB) | This study |

| BR7383 | attλ::(Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7384 | attλ::(Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB parS) attHK022::Spr | This study |

| BR7385 | attλ::(Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::(parS {−}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7386 | attλ::(Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB) attHK022::(parS {+}; Spr) | This study |

| BR7685 | P1 Kmr lysogen | 51 |

| BR8280 | attλ::cat | This study |

| BR8282 | attλ::(parS cat) | This study |

| BR8295 | attλ::cat attHK022::(Ppar-lacZ; Spr) | This study |

| BR8297 | attλ::(cat parS) attHK022::(Ppar-lacZ; Spr) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAH144 | R6K γori HK022attP; Spr. Plasmid dependent upon pir+ in host | 25 |

| pBEF102 | pBR327 Ptrp-parB parS; Apr | 19 |

| pBEF104 | pBR327 Ptrp-parB; Apr | 19 |

| pBEF119 | pBR327 Ptrp-parA parB; Apr | 19 |

| pBR322 | Multicopy cloning vector; Apr; Tcr | 3 |

| pGB2 | pSC101-based cloning vector; Spr | 7 |

| pHJ7 | pBR322 Ppar-lacZ promoter fusion plasmid; Apr | This study |

| pHJ24 | pGB2 Ppar-lacZ; Spr | This study |

| pHJ25 | Mini-RSF1010 lacIq Ptac-parA; Kmr | This study |

| pHJ29 | pLDR11 parS; Apr | This study |

| pHJ31 | pLDR11 cat | This study |

| pHJ32 | pLDR11 parS cat | This study |

| pHJ37 | pAH144 Ptrp-parB; Spr | This study |

| pHJ40 | pAH144 Ppar-lacZ; Spr | This study |

| pHJ41 | pAH144 lacIqPtac-parA Ptrp-parB; Spr | This study |

| pHJ44 | pAH144 Ppar-parA parB; Spr | This study |

| pHJ47 | pAH144 parS{+}; Spr | This study |

| pHJ47R | pAH144 parS{−}; Spr | This study |

| pHJ48 | pAH144 Ppar-parA parB parS; Spr | This study |

| pHJ49 | pLDR11 Ppar-parA parB; Apr | This study |

| pHJ50 | pLDR11 Ppar-parA parB parS; Apr | This study |

| pHJ56 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parA parB; Apr | This study |

| pHJ57 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parA parB parS; Apr | This study |

| pHJ98 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB; Apr | This study |

| pHJ100 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parA parB′::gfp::′parB parS; Apr | This study |

| pHJ104 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parB; Apr | This study |

| pHJ105 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parB parS; Apr | This study |

| pHJ106 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parB′::gfp::parB; Apr | This study |

| pHJ107 | pLDR11 Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB parS; Apr | This study |

| pLDR8 | pSC101ts source of λ Int; Kmr; plasmid lost on thermal induction | 14 |

| pLDR11 | pBR322 λattP plasmid; Apr | 14 |

| pMLO24 | pBR322 Ptrp-parA Apr | M. Łobocka |

| pMLO70 | pBR322 parS; Apr Tcr | M. Łobocka |

| pMLO87 | pBR322 Ppar-parA parB; Apr Tcr | 39 |

| pMLO102 | pBR322 Ptrp-parB; Apr | 39 |

| pMMB67EH | mini-RSF1010 lacIq Ptac; Kmr; low-copy-number cloning vector | M. Bagdasarian (46) |

| pOAR12 | pACYC184 lacIq Ptac-parB; Cmr | O. Rodionov |

| pOAR32 | mini-RSF1010 lacIqPtac-parB; Kmr | 51 |

| pPP112 | pBR322 PrepA (P1 coordinates 562-593)-lacZ promoter fusion; Apr | 54 |

| pOBK1 | pBR322 Ppar-parA parB::gfp; Apr | O. Bugajska |

| pRE7 | mini-RSF1010 lacIq Ptac-parA parB; Kmr | R. Edgar |

Recombinant DNA methods.

Standard recombinant DNA methods were used as described previously (53). Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), and T4 DNA ligase was from Life Technologies (Rockville, Md.). Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used in PCR amplification of specific genes. Preparation of plasmid DNA, gel purification of DNA fragments, and purification of PCR-amplified DNA fragments were performed using QIAprep Spin plasmid Miniprep, QIAquick gel extraction, and QIAquick PCR kits, respectively (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Insertions into the chromosome of MC1061 were performed at attλ according to previously described methods (14) and at attHK022 according to previously described methods (25). In every case, verification of single-copy insertion into attHK022 was performed by PCR analysis according to previously described methods (25), as multicopy insertions were not infrequent.

Constructions.

The pBR322-based reporter plasmid pHJ7 was constructed by insertion of a 186-bp P1 Ppar region, which included the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, upstream of the lacZ gene of pPP112 in place of PrepA. The Ppar region was PCR amplified from pOBK1 as template using primers HJP10 (5′-CGCGAATTCGCTACAACCTGAACGTAG) and HJP11 (5′-GGCGGATCCCGAAAGTCATCCTTTATG), and the product was cloned into pPP112 as an EcoRI-BamHI fragment. (Restriction enzyme recognition sites are underlined.) DNA sequencing of the Ppar region indicated the absence of mutations introduced during amplification. The pSC101-based reporter pHJ24 was constructed by cloning the EcoRI-BspEI fragment of Ppar-lacZ from pHJ7 into pGB2. An inducible source of ParA, pHJ25, was constructed from pRE7 (which carries the par genes fused to Ptac and its associated Shine-Dalgarno region) by cutting with MfeI and XmaI, blunting the ends with T4 DNA polymerase, and religating so as delete most of parB. pHJ29, used to insert parS into attλ, was constructed by PCR amplification of parS from pMLO70 as template with primers HJP34 (5′-GCCGAATTCACTTTCGCCATTCAAATTTCAC) and HJP35 (5′-GCGGAATTCCAAGGTGAAATCGTGGCGATT). The PCR product was cut with EcoRI and inserted into the EcoRI site of pLDR11. pHJ31, which was used to insert the cat gene into attλ, was constructed by ligation of the cat gene (excised from pST52 with PstI and blunt ended) to ScaI-cleaved pLDR11 (disrupting the bla gene). Insertion of the cat gene into pHJ29 analogously generated pHJ32. pHJ37, which was used to insert Ptrp-parB into the chromosome at the attHK022 site, was constructed by cloning the EcoRI-SalI fragment of pBEF104 into the multiple cloning site (MCS) of pAH144. pHJ40, which was used to insert Ppar-lacZ into the chromosome, was constructed by cloning the EcoRI-SalI fragment that includes Ppar-lacZ from pHJ24 into the MCS of pAH144. pHJ41, which was used to insert lacIq Ptac-parA with Ptrp-parB at the attHK022 site, was constructed by digestion of pOAR12 with XbaI and insertion of the smaller fragment, after blunting its ends, into the pHJ37 that had been digested with SalI and blunt ended. pHJ44, which was used to insert the par operon (lacking parS) into the chromosome, was the product of the cloning of a SalI-EcoRI fragment from pMLO87 into pAH144. Insertion of parS at the attHK022 site in both orientations involved pHJ47 and pHJ47R as intermediates. The PCR product used to construct pHJ29 was cut with EcoRI and cloned into the EcoRI site of pAH144 (within the MCS, which is flanked by terminators). The two orientations were distinguished by cutting with StyI. In pHJ47, the orientation of parS is such that the StyI site within parS is close to the attP site in pAH144. The orientation is the reverse in pHJ47R. pHJ48, which was used to insert the par operon with the adjacent parS locus, was constructed from pHJ44 by replacement of a MluI-EcoRI fragment of pHJ44 with a DNA fragment generated by MluI and EcoRI digestion of the PCR product obtained with pBEF102 as template and primers HJP1 (5′-CGGCATATG TCA AAG AAA AAC AGA CCA ACA) and HJP35. MluI cuts within parB. Sequencing of the replacement DNA indicated the absence of mutations introduced during amplification. pHJ49, which was used to insert the par operon (lacking parS) at attλ, is a clone of an EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pHJ44 in pLDR11. pHJ50, which was used to insert the par operon with the adjacent parS locus at attλ, is a clone into pLDR11 of an EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pHJ48. pHJ56, used to insert Ptrp-par AparB at attλ, was constructed by cutting pBEF119 with SalI, blunting the ends, and making a second cut with EcoRI, followed by cloning into pLDR11, which had been cut with EcoRI and SmaI. pHJ57, used to insert Ptrp-par Apar BparS at attλ, was constructed by the same strategy used to introduce parS into pHJ44, except that HJP35 was replaced with HJP42 (5′-GCGCTGCAGCAAGGTGAAATCGTGGCGATT) and the digestion of the PCR-amplified DNA and pHJ56 was with MluI and PstI. Sequencing of the replacement DNA indicated the absence of mutations introduced during amplification. pHJ98 and pHJ100, which were used in the construction of strains in which most of parB was replaced with gfp (equivalent in size to the replaced region), are derivatives of pHJ56 and pHJ57, respectively. The gfp gene was amplified by PCR with pGFPUV (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) as template and primers HJP66 (5′-CGGAATTCGG ATG AGT AAA GGA GAA GAA C) and HJP67 (5′-CCATTTCTTCAATGG TTA TTT GTA GAG CTC ATC CA). The start codon and the complement of the stop codon are underlined. The PCR product was cut with EcoRI and XcmI, and the resulting DNA was cloned into pHJ56 and into pHJ57 that had been digested with MfeI and XcmI. pHJ104 and pHJ105 are ΔparA versions of pHJ56 and pHJ57, respectively. They were constructed by digestion of those plasmids with EcoRI and XcmI and replacement of the excised fragment in each case with the smaller fragment of similarly digested pMLO102. pHJ106 and pHJ107, used to insert Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB and Ptrp-parB′::gfp::′parB parS into attλ, were constructed by replacing part of parB of pHJ104 and pHJ105 with gfp, as in the construction of pHJ98 and pHJ100. Colonies of strains carrying the plasmids which bore gfp fluoresced brightly under UV illumination, whereas those carrying only the chromosomally inserted gene did not.

Preparation of purified proteins.

ParA and ParB, His6-tagged at their C termini, were prepared from clones of parA and parB in the expression vector pET-23a+ (Novagen) that had been cut with NdeI and HindIII. The parA DNA was PCR amplified with pOBK1 as template and primers HJP22 (5′-CGCCATATG AGT GAT TCC AGC CAG CTT) and HJP23 (5′-GGCAAGCTT GTT AGA TCT GAT AAA TTC). The amplified DNA was cut with NdeI and HindIII. The parB DNA was PCR amplified with pMLO102 as template and primers pHJP1 (see above) and pHP3 (5′-GAAGCTT AGG CTT CGG CTT TTT ATC GAG). Purification of the proteins was with the His-Bind kit of Novagen. Purity was >95%.

P1 par promoter repression assay and protein quantitation.

E. coli strains were grown overnight from single colonies in LB broth with appropriate antibiotics. The cultures were diluted 3,000-fold into fresh medium and grown to early log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.2 to 0.3) and sampled to ice for determination of β-galactosidase specific activity or for immunoblotting. The specific activity of β-galactosidase was measured as described previously (45). Quantitation of proteins by immunoblotting was carried out as follows: cells from 1 ml of culture samples were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended at 1 to 2 OD600 units/ml in 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel-loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol), vortexed, and boiled for 4 min, and then 5 to 15 μl was loaded on a SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). After 1 h of blocking, rabbit serum containing antibodies to ParB (1:5,000), to a C-terminal peptide of ParA (1:2,000), or to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (1:2,000) (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) was added for 1 h. The ECL Western blotting analysis system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) was used to detect protein-antibody complexes. These were quantitated by scanning the bands in an Epi ChemII Darkroom (UVP Laboratory Products) and analyzing them using Labworks 3.02 software.

Microscopy.

For GFP visualization, live early-log-phase cells were viewed promptly after immobilization in 1% low-melting-point agarose in 0.9% NaCl on the surface of a microscope slide. Images were viewed with an Axiophot 2 fluorescence microscope equipped with a 100× oil immersion plan fluorite objective (Zeiss), and pictures were taken using a Micromax charge-coupled device camera.

RESULTS

Initial evidence for a regulatory role of parS in trans.

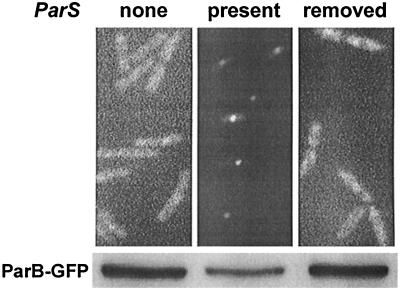

An unanticipated result was obtained in the course of experiments to determine the intracellular location of functional ParB tagged with GFP. The protein was supplied from a partition operon carried on a multicopy plasmid. Cells that also carried a chromosomally inserted parS locus displayed bright fluorescent foci corresponding to sites of ParB-GFP localization and much diminished background fluorescence in the cytoplasm. A similar effect had been seen using immunofluorescent visualization of ParB (17). Excision and subsequent loss of the parS locus by outgrowth of the bacteria restored the background fluorescence (Fig. 2, upper panels). Immunoblotting confirmed that the low background fluorescence in the presence of parS corresponded to a diminished cellular level of the ParB fusion protein (Fig. 2, lower panels). Since the partition genes in the operon were autogenously regulated, we expected that any ParB-GFP titrated by parS would be promptly replaced, leaving the background fluorescence unperturbed and causing the total concentration of ParB-GFP to be unaltered or somewhat increased. The roughly twofold decrease in the ParB-GFP concentration caused by a single parS locus acting on the expression of many copies of the partition operon suggested instead that parS can actively contribute to the negative regulation of the partition operon in trans to parS, at least under the conditions of our experiment.

FIG. 2.

Influence of a chromosomally inserted parS on the distribution and total amount of GFP-tagged ParB in E. coli carrying Ppar-parA parB::gfp in pBR322(pOBK1). Upper panels, from left to right, show fluorescence-phase micrographs of BR6902, the same strain into which parS had been inserted (BR6903), and a strain (BR8245) identical to BR6902 but derived from BR6903 by excision of parS by infection with an int+ xis+ Δattλ λimm434 bacteriophage (gift from R. A. Weisberg) and cured of the excised DNA by subsequent outgrowth. The lower panels show immunoblots of the GFP-tagged ParB detected with anti-ParB serum. Equal amounts of protein were loaded on the gels.

The alternative contributions of parS to partition operon regulation.

We had expected that parS might contribute to par operon regulation but only when in its normal location or close to it. We reasoned that upon binding at parS, ParB would normally spread to and reduce the efficiency of the promoters governing parB expression (51) but that if parS were deleted or displaced to a distant site from which ParB spreading could not reach the par operon, there would be no such effect. Deletion or displacement of parS was expected to result in only a modest increase in expression, in part because the level of ParB-mediated silencing of a gene transcribed towards parS, as are parA and parB, had been found to be much less than when the gene was inverted so as to be transcribed away from parS (O. Rodionov and M. Yarmolinsky, unpublished data).

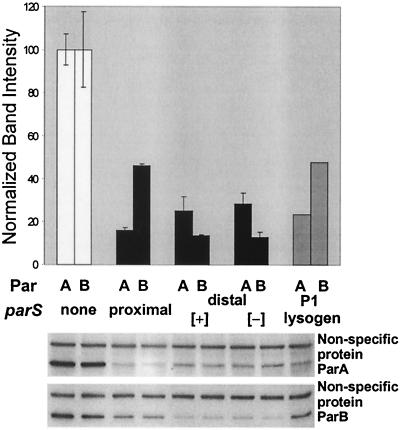

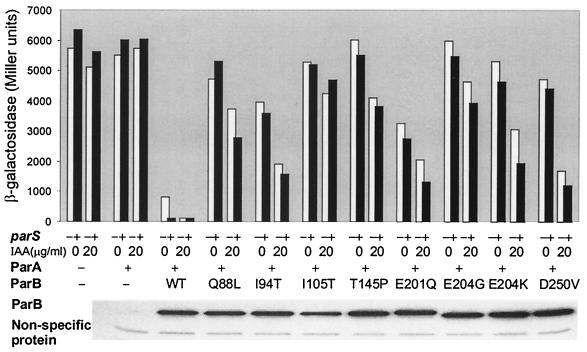

An experiment comparing the expression of the partition operon with parS in its normal location, displaced by several kilobases, or deleted, was performed with the relevant genes inserted in single copy in the E. coli chromosome. The partition operon was inserted at attλ, and the displaced parS was inserted at attHK022, about 250 kb away. Expression of the operon was assessed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3). The levels of ParA and ParB expression from the chromosomal par operon (Fig. 3, second pair of lanes from the left) are seen to be similar to the levels obtained from the par operon of an intact wild-type P1 prophage (rightmost lanes), consistent with the low copy number of P1 (48). Deletion of parS increased expression of the parA gene about sixfold and of the parB gene about twofold. Surprisingly, displacement of parS to a locus at a considerable remove from the partition operon resulted in less ParB protein than when parS was adjacent to parB. The latter results imply that an additional factor interferes with an assessment of the extent, if any, to which ParB spreading decreased parB expression.

FIG. 3.

Position effects on the contribution of parS to regulation. Immunoblots with anti-ParB serum are shown in the lower panel, and the band intensities normalized to those of a nonspecific protein are presented in the upper panel. The E. coli strains each carried the par operon inserted at attλ and a spectinomycin resistance gene at attHK022. The strains, from left to right, were BR7325 (parS deleted), BR7327 (parS included at the end of the par operon), BR7321 (parS inserted at attHK022), BR7321 (parS inverted with respect to its orientation in BR7323), and BR7685 (a P1 lysogen). Independent insertion events generated the pairs of strains tested. The graphed data are based on the average of the two separate determinations, except in the case of the P1 lysogen, where a single determination was made.

When parS was displaced too far from the par genes for ParB to mediate silencing of their expression by spreading over the intervening DNA, it nevertheless made a sevenfold contribution to negative regulation of the partition operon as judged by measurements of ParB. This contribution was independent of the orientation of parS, suggesting that parS can act independently of its immediate context. On the other hand, the possibility of context effects on the efficacy of parS is suggested by the diminished effect of parS when immediately downstream of parB. The data indicate that parS can cause a major decrease in expression of the partition operon. This effect is not due to provision of a site from which ParB can spread and cause gene silencing. Instead, the evidence offered in the next section indicates that the negative regulatory effect of parS is due to an enhancement of the repression of the par operon by ParA.

Dependence on ParA and ParB of the contribution of parS to partition operon repression.

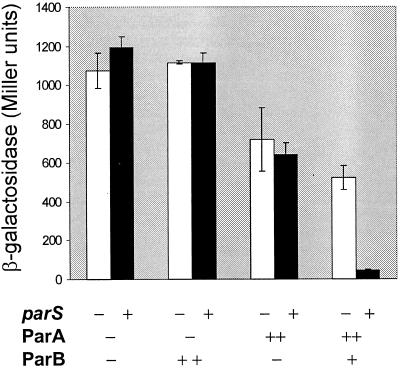

In order to assay transcriptional regulation of the partition operon conveniently, we constructed a promoter fusion of Ppar to lacZ and inserted it in the E. coli chromosome at attHK022. The regulatory effect of a chromosomal parS locus (at attλ) was tested in the presence of plasmids that supplied one, the other, or both P1 partition proteins (Fig. 4). In this experiment, the presence of both ParA and ParB caused only a twofold repression. The additional presence of parS augmented that repression 11-fold. The observed dependence of the parS effect upon ParB and of the ParB effect on ParA indicate that parS is a co-corepressor of the partition operon. The terms corepressor and co-corepressor are used without any implication as to the composition of the repression complex. The levels of ParA and ParB proteins supplied together from the uninduced mini-RSF1010 lacIq Ptac parA parB were equivalent, the ParA levels being greater than in a P1 lysogen and the ParB levels being less (data not shown). They were adequate to stabilize a mini-R1-based parS plasmid in trans (Rodionov and Yarmolinsky, unpublished). These results suggest that parS, acting as a co-corepressor, can make a significant contribution to the regulation of the P1 partition operon under essentially physiological conditions.

FIG. 4.

Dependence of the contribution of parS to repression on the presence of both ParA and ParB. The reporters of repression were BR8295 and BR8297, in which Ppar-lacZ was at the HK022 attachment site and parS, if present, was at the lambda attachment site. These strains were transformed with pBR322 and pMMB67EH (the mini-RSF1010 Ptac vector control), with MLO24 and pHJ25 (supplying ParA from both vectors), with pMLO102 and pOAR32 (supplying ParB from both vectors), or with pHJ25 and pRE7 (supplying ParA from pBR322 Ptrp-parA and both ParA and ParB from the pMMB67EH derivative). In this experiment, no inducer of either Ptrp or Ptac was present.

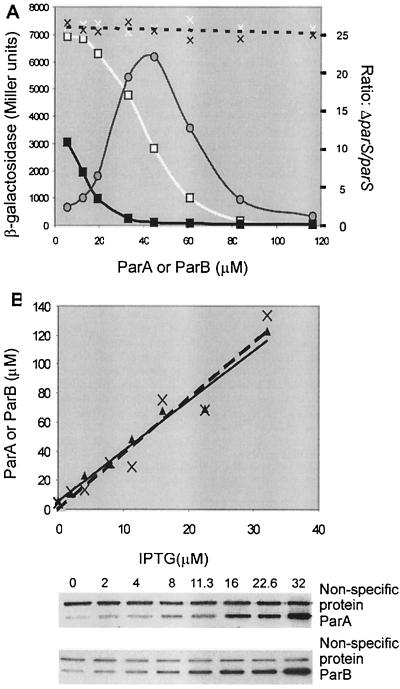

In the foregoing experiments, the contribution to repression made by parS varied considerably but so too did the concentrations of ParA and ParB. To determine how the concentrations of the partition proteins influence the magnitude of the parS effect, we made constructs that allowed us to regulate ParA and ParB levels at will, either in concert (Fig. 5A) or separately (Fig. 6). Immunoblotting provided an estimate of how the concentrations of these proteins varied with inducer concentration (Fig. 5B and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Repression of Ppar-lacZ as a function of the presence of ParA and ParB (supplied together) in the absence or presence of parS. (A) Relationship between repression and inducer concentration. Partition proteins supplied from a par operon under Ptac control (pRE7). The strains without and with parS were BR8280 and BR8282, respectively. The reporter of repression was a Ppar-lacZ inserted in pGB2 (pHJ24). Solid white line, parS absent; solid thick black line, parS present; solid thin black line, ratio; dotted line, control plasmid pMMB67EH substituted for pRE7. The data for the vector controls are indicated with white crosses for BR8280 and with black crosses for BR8282. Protein levels were approximately proportional to the concentration of inducer over the range shown, as seen in panel B. (B) Relationship between inducer and protein concentration. The graph of protein levels in cells grown with inducer at the indicated concentrations is based on the immunoblots with anti-ParB serum, using ParB His6-tagged at the C terminus as the standard and calculating the number of ParB dimers per cell (∼ equal to the number of ParA dimers per cell) by assuming that a viable cell count of a log-phase culture corresponds to 6.7 × 108 cells per OD600 unit, as determined separately. No significant interference with coordinate expression of the two proteins was caused by the separate parB promoter internal to parA, at least at the inducer concentrations at which the two proteins could be estimated.

FIG. 6.

Repression of Ppar-lacZ as a function of the presence of ParA and ParB, supplied from independently inducible sources, in the absence or presence of parS. Partition proteins were supplied from BR7377 (without parS) and BR7378 (with parS) in which the par genes are located at attHK022. ParA was inducible by IPTG, and ParB was inducible by IAA. The reporter of repression was pHJ7. Vector controls were pHJ7 transformants of BR8280 and BR8282 which do not encode Par proteins. Definitions of the lines in the graphs are as described for Fig. 5. Data are the averages of two or three experiments. Protein concentrations are deduced from immunoblots as described for Fig. 5 (data not shown). Molarities were approximated by assuming a cell volume of 1 fl; i.e., a concentration of 1 μM corresponds to about 600 molecules per cell.

Concerted regulation of the two partition proteins was achieved by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction of the par operon under Ptac control. The operon resided in a moderately low-copy-number plasmid (pRE7), the reporter of repression (Ppar-lacZ) on a separate compatible plasmid of comparable copy number (pHJ24). The contribution of a chromosomal parS to repression varied with the absolute concentrations of the Par proteins, attaining a maximum effect of more than 20-fold and dropping off to nil on both sides (Fig. 5A; see also Fig. 6). The concentration of ParB in cells that exhibited the maximum effect was about 14,000 dimers/cell, or six times that characteristic of a P1 lysogen (2,500 dimers/cell in our strain). We note, however, that as many as 7,000 dimers/cell have been reported in a different E. coli (P1) strain (23). ParA protein levels were comparable to those of ParB in this experiment, rather than considerably lower, as in a P1 lysogen.

Separate regulation of the two partition proteins was achieved with strains in which parA was under Ptac control, inducible by IPTG, and parB was under the control of the Serratia marcescens trp promoter (Ptrp), inducible by 3-β-indoleacrylic acid (IAA) (Fig. 6). The genes were inserted in the bacterial chromosome and thus enabled to produce lower levels of partition protein than under the conditions of Fig. 5A. The reporter of repression was pHJ7, a plasmid of higher copy number than the pHJ24 of Fig. 5A. Although the maximum stimulation of repression by parS was less dramatic than we routinely obtained with pHJ24, the results are consistent. The greatest effect of parS occurred at comparable concentrations of ParA and ParB, with both in excess of their normal levels. At levels of ParA and ParB that are similar to those in a P1 lysogen, the stimulation of repression by parS provided solely in trans was between two- and threefold.

An apparently catalytic action of parS in promoting repression.

The magnitude of the parS effect in the initial experiment depicted in Fig. 2 provided a hint that a single parS locus might be capable of repressing several par promoters. That conclusion is supported by the more quantitative experiment of Fig. 5A, in which a Ppar-lacZ reporter was carried by a plasmid of moderate copy number (pGB2) and, most dramatically, by the experiment of Fig. 6, in which the reporter was carried by pBR322. The β-galactosidase levels in the vector controls reflect the increase in reporter copy number in the experiments of Fig. 4, 5A, and 6. In the experiment depicted in Fig. 6, the ratio of reporter to parS was about 25:1. When ParA and ParB were each supplied at about 14 μM, the chromosomal parS locus sufficed to reduce lacZ expression by sixfold. This finding suggests that the action of parS may be catalytic and not, as suggested for F (59), direct. That is, it might not be necessary to invoke a pairing between the promoter region and the partition complex at the plasmid centromere that occludes the binding of RNA polymerase.

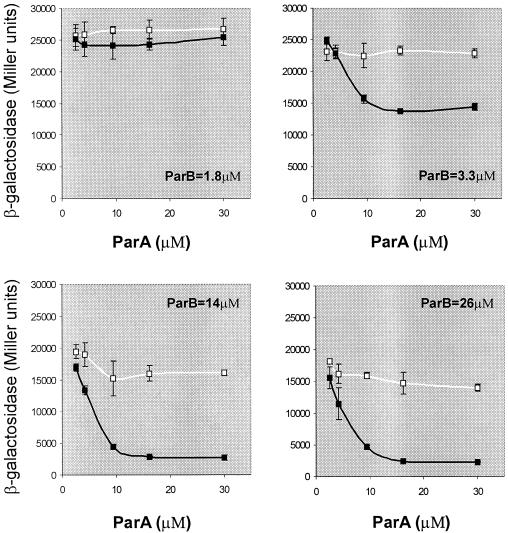

To determine whether spreading of ParB from parS might contribute to the efficacy of parS in promoting repression, we sought to block ParB spreading by physical roadblocks or by use of spreading-defective ParB mutants. Roadblocks proved to be unsatisfactory, because modest decreases in repression seen with roadblocks that closely flanked parS (data not shown) could be attributed to effects on the accessibility of parS itself to ParB or ParA. Although mutant ParB also proved unsatisfactory for our purposes, we report our findings because they reveal an unexpected feature of the mutant proteins, namely their deficiency as corepressors.

We examined the repressor activity of spreading-defective ParB in the presence or absence of a single chromosomal parS (Fig. 7). To be sure that we were supplying the mutant proteins in sufficient quantity, we used an inducible source carried by a pBR322 vector and showed by immunoblotting that substantial protein levels were achieved. The Par proteins were at high levels even in the absence of inducer. Consequently, the level of repression by ParA in the presence of wild-type ParB was about sevenfold and became about 50-fold in the presence of both wild-type ParB and parS. Increasing the level of ParB reduced lacZ expression to about the same low level whether parS was present or not. The spreading-defective mutants, on the other hand, showed remarkably little capacity to act as corepressors. At low levels of corepressor activity, it is difficult to interpret the evident low or negligible response of the mutants to the presence of parS. While frustrating in this regard, the results do suggest a relationship between conformational changes that allow ParB to spread along DNA and those required for communication with ParA.

FIG. 7.

Limited capacity of spreading-defective ParB mutants to act as corepressors. Repression of the Ppar-lacZ present on the plasmid pHJ7 was measured in strains BR8280 and BR8282 transformed with plasmid sources of the partition proteins (i.e., in the absence or presence of a single chromosomal parS). ParA was supplied from pJH25 induced with 10 μM IPTG and ParB from pMLO102 in the absence or presence of 20 μg of IAA/ml as inducer. The ParB mutant proteins were described previously (39) and have been further characterized (16, 51). The immunoblots shown, which reveal that the mutant and wild-type ParB proteins were at comparable levels, were the results of immunoblotting performed on the transformants of BR8282. IPTG (10 μM) and IAA (20 μg/ml) were present during growth. Similar results were obtained with transformants of BR8280 (data not shown).

An enhanced expression of parB that is mediated in cis by parS.

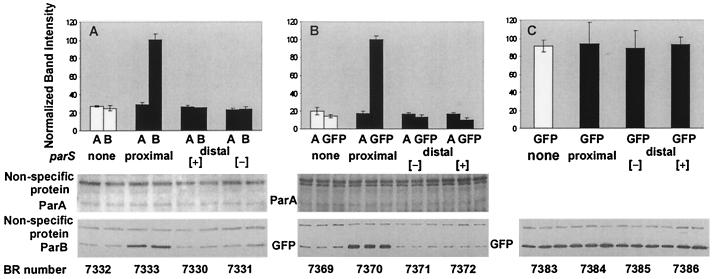

The extent to which ParB-mediated silencing decreased the expression of the par genes could not be assessed in the experiments depicted in Fig. 3 because of the enhanced repression mediated by parS. In experiments designed to avoid that complication by replacement of the par promoter with a trp promoter, we observed that the levels of ParA appeared unaffected by deletion or displacement of parS (Fig. 8A). Silencing is thus unlikely to be a major factor in autoregulation of the operon as a whole. In contrast, we noted that deletion or displacement of parS resulted in a significant decrease in the level of ParB.

FIG. 8.

Position effects on the contribution of parS to regulation of genes under Ptrp control. Protein levels were determined from the immunoblots shown below and were normalized on the basis of the nonspecific protein bands. The values are plotted for each set of constructs in arbitrary units, with 100 units taken as the highest average level. (A) Experiment identical to that of Fig. 3, except that Ppar was replaced by Ptrp. The bar graph is based on averages of two values. (B) As described for panel A, except that parB was replaced by parB′::gfp::′parB and GFP was assayed in place of ParB. The bar graph is based on the averages of three values. (C) As described for panel B, except that parA was deleted. The bar graph is based on the averages of three values.

To determine whether the dependence of ParB levels on the adjacent parS locus was mediated by a complex of ParB with parS or by parS itself, we examined the effect of substituting a gfp gene (including its translational stop codon) for an internal segment of parB of equivalent size. The replacement of 3/4 of parB by gfp appeared not to alter the stimulatory effect of parS on the expression of the gene immediately upstream. The production of GFP was severalfold higher than when parS was absent or displaced to a distant location (Fig. 8B). Evidently ParB is not essential for the parS-dependent enhancement of protein levels. When the parA gene (including any internal promoters of parB) was deleted, the level of GFP reached an elevated level in each of the strains tested (Fig. 8C). If mRNA stability is involved in the cis-specific effect of Fig. 8A and B, then the results of Fig. 8C suggest that the presence of parS at the mRNA terminus can counteract an instability of the mRNA that depends on sequences that are eliminated by deletion of parA.

A possible function of this cis-specific effect is to counteract the cis-specific gene silencing due to ParB spreading upstream of parS and thereby assist in ensuring appropriate par gene expression for partitioning. Alternatively, the effect may be an artifact of the constructions, which alter the 3′ end of the mRNAs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have reinvestigated the manner by which the P1 partition proteins cooperate to regulate the P1 par operon. Our main contribution is the finding that the P1 centromere analog, parS, can play an important, possibly catalytic role in that regulation. The P1 par operon is one of several partition operons that are regulated by the concerted action of both the proteins that they encode (24, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 47, 55). Regulation of the partition operon of F appears also to be affected by the F-specific centromere sopC acting to enhance SopA-mediated repression (59). It remains to be determined whether centromere participation in the autoregulatory circuit is a common feature of partition operons.

The most provocative result that we describe here is the capacity of a single parS inserted within the bacterial chromosome to enhance by severalfold the repression of a gene carried by a multicopy reporter plasmid. Two kinds of models can be proposed to account for the magnitude of the effect, one stoichiometric, the other catalytic. The stoichiometric model requires that ParB has spread into DNA flanking parS. The catalytic model, while possibly affected by spreading, does not require it.

According to the stoichiometric model, parS alters ParA dimers that are bound to the complex of ParB with flanking DNA. The conformational change makes the bound ParA dimers into more effective repressors. Pairing of such altered ParA dimers with par promoter regions would be sterically cumbersome: the repression observed in the experiments of Fig. 5A and 6 would require the packing of many par promoter regions, each borne on a separate plasmid, onto the ParB-covered DNA flanking parS. Pairing appears inconsistent with the observation that large separations of parS from the reporter of repression, when both are chromosomal, did not affect the capacity of parS to augment repression (compare the findings described in reference 38). It also appears inconsistent with the absence of ParA foci in cells carrying a mini-P1 plasmid and a source of physiological levels of the Par proteins (17). On the other hand, the several mutant forms of ParB that retain the capacity to bind to parS in vitro but have lost the capacity to spread from parS (39, 51) proved to be highly defective as corepressors, with parS present or not (Fig. 7). Whether the corepression defect is due to the inability to spread per se or to an associated defect in communicating with ParA is presently unclear.

According to the catalytic model, parS makes free ParA more effective as a repressor (5). The complex of ParB with parS (and perhaps also with the flanking DNA) would be the catalyst, and the hydrolysis of ATP bound to ParA would provide the energy for the reaction. The experiments undertaken to discriminate between these models are presently inconclusive.

What might be the biological significance of the substantial effects of parS that we describe here? We have already mentioned in the previous section that the in cis stimulatory effect of parS on ParB levels, if it is not a construction artifact, may serve to antagonize the silencing effect of ParB. The balance between the intrinsic transcription rate of the parB gene and the silencing of that transcription by ParB protein must be poised at a level that permits ParB to reach concentrations as high as 7,000 dimers per cell (24). Possibly parS plays a dual role in situating this balance.

Concerning the in trans effect of parS, two very different points of view may be maintained. One is to look at this effect as contributing to a regulatory mechanism that, while dispensable for partitioning, can make the process more efficient. This view follows from the observation that a parS plasmid can be actively partitioned by partition proteins supplied from constitutive sources. The other view is to consider that the catalytic action of parS is intrinsic to its function as the plasmid centromere—not just a fine-tuning mechanism. We examine each possibility in turn.

The enhancement of repression by parS acting in trans could be used to respond to the number of parS loci and the extent to which ParB and IHF are bound to them. Supernumerary parS loci in trans are known to exert partition incompatibility, that is they can impair the partitioning activity of a resident plasmid (1). Traditionally, the causes of partition incompatibility have been attributed to competition by the extra parS loci for partition sites or proteins or to the formation of heterologous plasmid pairs. Our findings and the comparable findings reported for F (59) suggest that among possible causes of partition incompatibility, a regulatory component should not be neglected.

The view that the catalytic action of parS in promoting an alteration in ParA might be intrinsic to its function as the plasmid centromere is suggested by a consideration of the roles of MinD and MinE in cell division (reviewed in reference 52). MinD self-assembles on the bacterial membrane and recruits to it MinC (an inhibitor of septation) and MinE (a topological specificity factor that also suppresses the septation inhibitor activity of MinC). MinE displaces the MinD at its flanks from the membrane, a peeling process that comes to rest near the pole and then resumes as a shortage of free MinE permits the accumulation of a new source of membrane-bound MinD at the opposite pole (43). That membrane-bound MinD then proceeds to attract MinE. During the cell cycle, the MinC/MinD complex oscillates between the two cell poles (50), a behavior that certain other members of the ParA family have been shown more recently to exhibit (2, 15, 41, 49). The oscillation of MinC/MinD is considered to be part of a dynamic pattern-forming mechanism that is presumed to involve local autocatalysis, a relatively long-range lateral inhibition, and no requirement for prelocalized determinants (43). The model predicts that the association of MinD and MinE with the membrane is autocatalytic, and in this case, the lateral inhibition is most simply explained by substrate depletion. The lateral inhibition ensures that the regions at which MinC/MinD complexes accumulate, and thus where autocatalytic polymerization of FtsZ is inhibited, are adequately separated.

Parallels between the placing of barriers to septation and the positioning of plasmids are evident both at the level of formal analysis and at the level of biochemistry. Just as MinD oscillation requires a stimulation of its ATPase activity by MinE (31), so oscillation of Soj (the ParA homolog encoded by Bacillus subtilis) requires the stimulation of Soj ATPase activity by Spo0J (the corresponding ParB protein) (41, 49). Similarly, an oscillation in E. coli of a fusion protein between a ParA of the virulence factor pB171 and GFP was reported to depend on the conjugate ParB protein and the plasmid centromere. Moreover, point mutations in the Walker A box ATPase motif of the pB171 ParA simultaneously abolished plasmid partitioning and ParA-GFP oscillation (15). The stimulation of repression of the P1 partition operon by parS is likely due to the stimulation of the ATPase activity of ParA by the ParB-parS complex.

If the principles of pattern formation by local autocatalysis and lateral inhibition apply here, as they do so widely in developmental biology (44, 57), then the pressing questions become those of the identification of the relevant autocatalytic and inhibitory functions. We suggest that parS might have a critical role in both parts of the process. It might act as a nucleation site for an autocatalytic reaction that associates the partition complex with the cell membrane, and it might simultaneously assist in depleting the active form of ParA.

This model dispenses with initial pairing as a prerequisite for plasmid partitioning. In the case of P1, the relevance of plasmid pairing to partitioning is still uncertain. Initially unpaired nonreplicating DNA rings can be partitioned by P1 Par proteins supplied in trans (56), although there is also evidence that parS sites (carried by the DNA rings) can be paired by ParB (16).

The present study was initiated because of our finding that a single chromosomal copy of parS could deplete free ParB-GFP from the cytoplasm. During the act of partitioning, the complex of proteins bound to parS is presumably associated with the cell membrane. Depletion of a partition protein from the cytoplasm and its involvement in a possibly autocatalytic association with the membrane can be viewed in the context of pattern formation by local self-enhancement and lateral inhibition. Studies of partition protein binding to the cell membrane that may bear upon the value of this viewpoint are being undertaken.

Acknowledgments

We thank our National Institutes of Health colleagues Oleg Rodionov, Rotem Edgar, and Dhruba Chattoraj for helpful advice and Richard Fekete for providing independent confirmation of the fluorescent imaging results of Fig. 1. Sources of bacterial strains and plasmids are indicated in the text. Antisera were kindly supplied by the laboratories of Barbara Funnell and Stuart Austin, and phage insertion kits were kindly supplied by the laboratories of Walter Messer and Barry Wanner. DNA sequencing was performed by Mark Miller of the National Cancer Institute DNA Sequencing Minicore Facility. We are grateful to Ding Jin and Małgorzata Łobocka for a critical reading of the manuscript.

J.-J.H. was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austin, S., and K. Nordström. 1990. Partition-mediated incompatibility of bacterial plasmids. Cell 60:351-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autret, S., R. Nair, and J. Errington. 2001. Genetic analysis of the chromosome segregation protein Spo0J of Bacillus subtilis: evidence for separate domains involved in DNA binding and interactions with Soj protein. Mol. Microbiol. 41:743-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolivar, F., R. L. Rodriguez, P. J. Greene, M. C. Betlach, H. L. Heyneker, and H. W. Boyer. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bork, P., C. Sander, and A. Valencia. 1992. An ATPase domain common to prokaryotic cell cycle proteins, sugar kinases, actin, and hsp70 heat shock proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7290-7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouet, J. Y., and B. E. Funnell. 1999. P1 ParA interacts with the P1 partition complex at parS and an ATP-ADP switch controls ParA activities. EMBO J. 18:1415-1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchward, G., D. Belin, and Y. Nagamine. 1984. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene 31:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davey, M. J., and B. E. Funnell. 1997. Modulation of the P1 plasmid partition protein ParA by ATP, ADP, and P1 ParB. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15286-15292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey, M. J., and B. E. Funnell. 1994. The P1 plasmid partition protein ParA. A role for ATP in site-specific DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29908-29913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, M. A., and S. J. Austin. 1988. Recognition of the P1 plasmid centromere analog involves binding of the ParB protein and is modified by a specific host factor. EMBO J. 7:1881-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, M. A., K. A. Martin, and S. J. Austin. 1992. Biochemical activities of the parA partition protein of the P1 plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1141-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis, M. A., K. A. Martin, and S. J. Austin. 1990. Specificity switching of the P1 plasmid centromere-like site. EMBO J. 9:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, M. A., L. Radnedge, K. A. Martin, F. Hayes, B. Youngren, and S. J. Austin. 1996. The P1 ParA protein and its ATPase activity play a direct role in the segregation of plasmid copies to daughter cells. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1029-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diederich, L., L. J. Rasmussen, and W. Messer. 1992. New cloning vectors for integration in the lambda attachment site attB of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Plasmid 28:14-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebersbach, G., and K. Gerdes. 2001. The double par locus of virulence factor pB171: DNA segregation is correlated with oscillation of ParA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15078-15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgar, R., D. K. Chattoraj, and M. Yarmolinsky. 2001. Pairing of P1 plasmid partition sites by ParB. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1363-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdmann, N., T. Petroff, and B. E. Funnell. 1999. Intracellular localization of P1 ParB protein depends on ParA and parS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14905-14910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman, S. A., and S. J. Austin. 1988. The P1 plasmid-partition system synthesizes two essential proteins from an autoregulated operon. Plasmid 19:103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funnell, B. E. 1988. Mini-P1 plasmid partitioning: excess ParB protein destabilizes plasmids containing the centromere parS. J. Bacteriol. 170:954-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funnell, B. E. 1991. The P1 plasmid partition complex at parS. The influence of Escherichia coli integration host factor and of substrate topology. J. Biol. Chem. 266:14328-14337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Funnell, B. E. 1988. Participation of Escherichia coli integration host factor in the P1 plasmid partition system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6657-6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funnell, B. E., and L. Gagnier. 1993. The P1 plasmid partition complex at parS. II. Analysis of ParB protein binding activity and specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 268:3616-3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funnell, B. E., and L. Gagnier. 1994. P1 plasmid partition: binding of P1 ParB protein and Escherichia coli integration host factor to altered parS sites. Biochimie 76:924-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerdes, K., and S. Molin. 1986. Partitioning of plasmid R1. Structural and functional analysis of the parA locus. J. Mol. Biol. 190:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldimann, A., and B. L. Wanner. 2001. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:6384-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanai, R., R. Liu, P. Benedetti, P. R. Caron, A. S. Lynch, and J. C. Wang. 1996. Molecular dissection of a protein SopB essential for Escherichia coli F plasmid partition. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17469-17475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes, F., and S. Austin. 1994. Topological scanning of the P1 plasmid partition site. J. Mol. Biol. 243:190-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes, F., and S. J. Austin. 1993. Specificity determinants of the P1 and P7 plasmid centromere analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9228-9232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes, F., L. Radnedge, M. A. Davis, and S. J. Austin. 1994. The homologous operons for P1 and P7 plasmid partition are autoregulated from dissimilar operator sites. Mol. Microbiol. 11:249-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirano, M., H. Mori, T. Onogi, M. Yamazoe, H. Niki, T. Ogura, and S. Hiraga. 1998. Autoregulation of the partition genes of the mini-F plasmid and the intracellular localization of their products in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:392-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, Z., and J. Lutkenhaus. 2001. Topological regulation of cell division in E. coli. spatiotemporal oscillation of MinD requires stimulation of its ATPase by MinE and phospholipid. Mol. Cell 7:1337-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagura-Burdzy, G., K. Kostelidou, J. Pole, D. Khare, A. Jones, D. R. Williams, and C. M. Thomas. 1999. IncC of broad-host-range plasmid RK2 modulates KorB transcriptional repressor activity in vivo and operator binding in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 181:2807-2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen, R. B., M. Dam, and K. Gerdes. 1994. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The parA operon is autoregulated by ParR and its transcription is highly stimulated by a downstream activating element. J. Mol. Biol. 236:1299-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen, R. B., and K. Gerdes. 1997. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The ParM protein exhibits ATPase activity and interacts with the centromere-like ParR-parC complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269:505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalnin, K., S. Stegalkina, and M. Yarmolinsky. 2000. pTAR-encoded proteins in plasmid partitioning. J. Bacteriol. 182:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, S. K., and J. C. Wang. 1999. Gene silencing via protein-mediated subcellular localization of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8557-8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, S. K., and J. C. Wang. 1998. Localization of F plasmid SopB protein to positions near the poles of Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1523-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer, H., M. Niemoller, M. Amouyal, B. Revet, B. von Wilcken-Bergmann, and B. Muller-Hill. 1987. lac repressor forms loops with linear DNA carrying two suitably spaced lac operators. EMBO J. 6:1481-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Łobocka, M., and M. Yarmolinsky. 1996. P1 plasmid partition: a mutational analysis of ParB. J. Mol. Biol. 259:366-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch, A. S., and J. C. Wang. 1995. SopB protein-mediated silencing of genes linked to the sopC locus of Escherichia coli F plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1896-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marston, A. L., and J. Errington. 1999. Dynamic movement of the ParA-like Soj protein of B. subtilis and its dual role in nucleoid organization and developmental regulation. Mol. Cell 4:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin, K. A., M. A. Davis, and S. Austin. 1991. Fine-structure analysis of the P1 plasmid partition site. J. Bacteriol. 173:3630-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meinhardt, H., and P. A. de Boer. 2001. Pattern formation in Escherichia coli: a model for the pole-to-pole oscillations of Min proteins and the localization of the division site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14202-14207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meinhardt, H., and A. Gierer. 2000. Pattern formation by local self-activation and lateral inhibition. Bioessays 22:753-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Morales, V. M., A. Backman, and M. Bagdasarian. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mori, H., Y. Mori, C. Ichinose, H. Niki, T. Ogura, A. Kato, and S. Hiraga. 1989. Purification and characterization of SopA and SopB proteins essential for F plasmid partitioning. J. Biol. Chem. 264:15535-15541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prentki, P., M. Chandler, and L. Caro. 1977. Replication of prophage P1 during the cell cycle of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 152:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quisel, J. D., D. C. Lin, and A. D. Grossman. 1999. Control of development by altered localization of a transcription factor in B. subtilis. Mol. Cell 4:665-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raskin, D. M., and P. A. de Boer. 1999. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4971-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodionov, O., M. Łobocka, and M. Yarmolinsky. 1999. Silencing of genes flanking the P1 plasmid centromere. Science 283:546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rothfield, L., S. Justice, and J. Garcia-Lara. 1999. Bacterial cell division. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:423-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 54.Sozhamannan, S., and D. K. Chattoraj. 1993. Heat shock proteins DnaJ, DnaK, and GrpE stimulate P1 plasmid replication by promoting initiator binding to the origin. J. Bacteriol. 175:3546-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabuchi, A., Y. N. Min, D. D. Womble, and R. H. Rownd. 1992. Autoregulation of the stability operon of IncFII plasmid NR1. J. Bacteriol. 174:7629-7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Treptow, N., R. Rosenfeld, and M. Yarmolinsky. 1994. Partition of nonreplicating DNA by the par system of bacteriophage P1. J. Bacteriol. 176:1782-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turing, A. M. 1952. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 237:37-72.

- 58.Yarmolinsky, M. 2000. Transcriptional silencing in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yates, P., D. Lane, and D. P. Biek. 1999. The F plasmid centromere, sopC, is required for full repression of the sopAB operon. J. Mol. Biol. 290:627-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Youngren, B., and S. Austin. 1997. Altered ParA partition proteins of plasmid P1 act via the partition site to block plasmid propagation. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1023-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]