Abstract

Most bacteria contain one type I signal peptidase (SPase) for cleavage of signal peptides from secreted proteins. The developmental complex bacterium Streptomyces lividans has the ability to produce and secrete a significant amount of proteins and has four different type I signal peptidases genes (sipW, sipX, sipY, and sipZ) unusually clustered in its chromosome. Functional analysis of the four SPases was carried out by phenotypical and molecular characterization of the different individual sip mutants. None of the sip genes seemed to be essential for bacterial growth. Analysis of total extracellular proteins indicated that SipY is likely to be the major S. lividans SPase, since the sipY mutant strain is highly deficient in overall protein secretion and extracellular protease production, showing a delayed sporulation phenotype when cultured in solid medium.

Bacterial preproteins exported by the general secretion pathway (Sec pathway) contain a signal peptide required for correct translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane (9, 26, 34, 35); upon translocation, a type I signal peptidase (SPase) removes the signal peptide so that the mature protein is released from the membrane (8). Prokaryotic type I SPases, also known as leader peptidases (Lep), process the majority of exported preproteins. Most organisms contain only one type I SPase which seems to be essential, as is the case with Escherichia coli (8, 32) or yeast (3). There are other organisms containing two paralogous type I SPases, such as Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (10) and most eukaryotic species (9). At least two SPases have been described in the bacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (14, 22) and Staphylococcus aureus (7); three have been found in Deinococcus radiodurans (36) and in the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus (17). Seven SPases have been described for the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis, where the genes corresponding to five of them (SipS, SipT, SipU, SipV, and SipW) are widespread on the chromosome (33, 30) and two other genes (SipP) have been found in plasmids (22).

Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the Streptomyces genus are soil bacteria with mycelial growth that undergo a complex biochemical and morphological differentiation prior to the formation of exospore chains (6). Streptomycetes produce and secrete large quantities of proteins (12), and Streptomyces lividans in particular has often been used as a host for secretory production of heterologous proteins (1, 2, 12, 20, 34). Four adjacent genes (sipW, sipX, sipY, and sipZ) encoding different type I signal peptidases have been identified in the S. lividans TK21 genome, where three of the sip genes (sipW, sipX, and sipY) constitute an operon and the fourth (sipZ) is the first gene of another operon encompassing three additional unrelated genes (26). We describe here the construction and in vivo phenotypical characterization of mutants in each of the four S. lividans sip genes. The analysis indicates that SipY appears to be the S. lividans SPase playing a major role in preprotein processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

S. lividans TK21 (15) used as the wild-type strain was cultured in liquid NMMP medium or solid R5 medium as indicated (15). Thiostrepton (5 μg/ml) or kanamycin (10 μg/ml) was added to the media when required. S. lividans TK21W26, S. lividans TK21X516, S. lividans TK21Y62, and S. lividans TK21Z1 are the sipW, sipX, sipY, and sipZ mutant strains, respectively. E. coli K514 (23) and E. coli ET12567 (21) were cultured in Luria broth (LB) (32) and were used for plasmid propagation. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) was added to the media when needed. Plasmids pSN425 and pSN426 are pUC18 derivatives containing the cluster of S. lividans sip genes and were used to construct sipY and sipX mutants, respectively. Plasmid pSN408 is a pUC18 derivative containing the sipW gene and was used to construct the sipW mutant. Plasmid pAC301 (obtained from F. Malpartida), a pUC18 (37) derivative carrying a 1,060-bp long BclI DNA fragment encoding the thiostrepton resistance gene (tsr [15]), was used to construct the sipZ mutant. The tsr marker was constituted by a 1,060-bp EcoRI-XbaI fragment obtained from plasmid pGM9 (24). Multicopy plasmid pAGAs5 is a pAGAs1 (25) derivative containing the S. coelicor agarase gene (dagA); the tsr gene of pAGAs5 was inactivated by a frameshift mutation so that pAGAs5 could be propagated in the different S. lividans sip mutant strains.

DNA manipulation and PCR amplification.

General recombinant DNA manipulation was carried out as described previously (15, 27). Restriction endonucleases and DNA modifying enzymes were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim, Promega, and Ecogene. S. lividans chromosomal DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification by incubation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of incubation at 95°C (1 min), 45°C (1 min), and 72°C (2 min), with a final extension cycle of 10 min at 72°C.

Expression and purification of the hexahistidine-tagged Sip proteins for antibody preparation.

Expression and purification of the N-terminally hexahistidine-tagged Sip proteins was performed as described previously (11). Purified SPases were used to raise polyclonal antibodies in rabbits. Purified SPase preparations (50 μg in 500 μl) were mixed with 500 μl of complete Freund adjuvant and injected intramuscularly (twice, 1 ml each time) in a Hollander rabbit (Pfd:HOL) with an interval of 3 weeks. At 2 weeks after applying the last injection, a blood sample was taken and the serum collected by centrifugation (5 min, 150 × g) was prepared as described previously (10). Polyclonal antibodies against agarase were obtained as described previously (25).

Construction of mutants.

Plasmids pSN425 and pSN426 were used to obtain the appropriate deletion mutants by inserting a 1,060-bp EcoRI-XbaI DNA fragment encoding the thiostrepton resistance gene depleted of its transcription termination sequence (tsr [15]), thereby generating plasmids pSN-Y and pSN-X, respectively. Plasmid pSN408 was used to produce the sipW mutant by inserting the 1,060-bp EcoRI-XbaI fragment containing the tsr gene, thereby generating plasmid pSN-W. Plasmid pSN425 is a pUC18 derivative carrying the 3.45-kb oligonucleotide sn30 (5′-CTGCGCGAGCTGCGCGGCAAGGC-3′)-SphI, with a DNA fragment comprising the four sip genes and ending at the SphI site located right behind sipZ (26). Plasmid pSN426 is a pUC18 derivative that carries a 3.06-kb DNA fragment spanning from the BbrPI site within the sipW coding sequence to the SphI site downstream of sipZ (26). Plasmid pSN408 is a pUC18 derivate carrying a 1,847-bp NcoI DNA fragment encoding sipW (26).

To delete sipY and inactivate sipX and sipW, S. lividans TK21 was transformed with plasmids pSN-Y, pSN-X, and pSN-W, respectively. In pSN-Y, the pSN425 399-bp PstI fragment (P2-P3, comprising SipY boxes D and E; Fig. 1) was replaced by the tsr marker; in pSN-X, tsr was inserted at the StuI site of pSN426 (St2, between SipX boxes C and D; Fig. 1); and in pSN-W, tsr was inserted at an MluI site of pSN408 (Ml, between SipW boxes C and D; Fig. 1). For sipZ insertional inactivation, a 315-bp sipZ internal DNA fragment (comprising SipZ box B to the middle of sipZ box E) was PCR amplified from the S. lividans chromosomal DNA by using the oligonucleotides sn49 (5′-CGCGGATCCGCCGACCAGCTCGAATGACGCCGACG-3′) and sn3 (5′-CGCGGATCCGTTGCGCCGCTCGTCGCCCAGCAG-3′) as forward and reverse primers, respectively; the amplified DNA fragment was digested with restriction endonuclease BamHI and inserted into the BamHI site located dowstream of tsr in plasmid pAC301, resulting in plasmid pSN-Z. The E. coli ET12567 triple methylase mutant strain (21) was used as a host to propagate pSN plasmids.

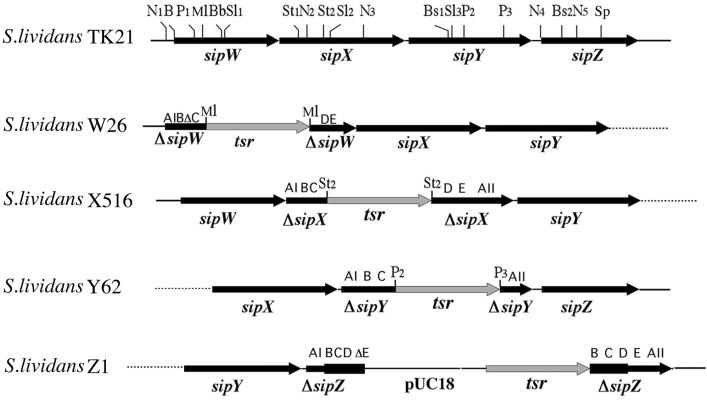

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal organization of disrupted S. lividans sip genes. Relevant restriction endonuclease sites are indicated: BamHI (B), BbrPI (Bb), BstUI (Bs), MluI (Ml), NcoI (N), PstI (P), SalI (Sl), StuI (St), SphI (Sp). Conserved typeI SPase boxes (AI, B, C, D, E, and AII [26]) are indicated.

Mutations in sipW, sipX, and sipY genes were constructed by transformation of S. lividans TK21 protoplasts with linearized and purified plasmids pSN-W, pSN-X, and pSN-Y containing the respective tsr-disrupted sip genes. The correct integration of linearized DNA fragments or plasmid pSN-Z in the chromosome of S. lividans that gave rise to mutant strains S. lividans TK21W26, S. lividans TK21X516, S. lividans TK21Y62, and S. lividans TK21Z1, respectively (Fig. 1), was verified by PCR and Southern blot hybridization analysis (not shown).

Optical microscopy.

Cultures for phase-contrast microscopy of spore-forming hyphae were set up by inserting a sterile coverslip at a 45° angle into NMMP agar and inoculating in the acute angle along the glass surface (5). Coverslips were removed after 6 days of incubation at 30°C, and the cells on the coverslip surface were fixed and mounted for microscopy. Samples were studied and photographed by using a Zeiss Axiolab HBO 50 microscope equipped for phase-contrast microscopy.

Extracellular protein analysis and Western blot experiments.

Total extracellular proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 15% polyacrylamide gel (19). For SPase Western blot analysis, intracellular proteins were fractionated by SDS-12.5% PAGE and transferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp.) as described previously (29). Half of the transferred material was stained with 1% (wt/vol) Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 in 50% (vol/vol) methanol and 20% (vol/vol) acetic acid for 15 min. The other half of the transferred material was incubated with antibodies raised against SPases, followed by a further incubation with 0.1 μCi of 125I-labeled protein A from Staphyloccocus aureus (Amersham, Plc.) ml−1, revealed peptides reacting with the antibodies, as described previously (29). Membranes were exposed to Agfa Curix RP2 film at −70°C. The protein concentrations in the different samples were determined as described previously (4) by using standard I bovine gamma globulin (Bio-Rad).

Enzyme activities.

To determine the extracellular activities, supernatants from 20-ml aliquots of bacterial cell cultures at the indicated phases of growth were concentrated by precipitation with ammonium sulfate brought to 80% saturation; the precipitated protein was collected by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 min and dissolved in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8). The total amount of protein present in the assay was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein determination kit, as indicated by the supplier. To assay protease activities, different aliquots were brought to a 1-ml final volume of 0.1 M imidazole-HCl (pH 7.2) in the presence of 7 mg of Hide Powder Azure (Sigma Chemical Co.) and incubated at 37°C until the blue color developed as described previously (25). One enzyme unit was defined as the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzes 1 mg of Hide Power Azure in a 30-min incubation at 30°C (13). To assay the extracellular presence of the subtilisin inhibitor, aliquots were brought to a 250-μl final volume of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.6) in the presence of 2.85 × 10−4 U of subtilisin (Sigma Chemical Co.) and a 0.25 mM concentration of the N-succinyl-l-Ala-l-Ala-l-Pro-l-Phe-p-nitroanilide (sAAPF-pNA) (Sigma Chemical Co.) as the substrate, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C until the yellow color developed as described previously (18). The presence of the subtilisin inhibitor was referred as a percentage of subtilisin activity remaining after the incubation period.

To determine isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH) activity, bacterial cells present in 20-ml aliquots of bacterial cell cultures at the indicated phases of growth were harvested and lysed (15). Different aliquots from the lysates were brought to a 1-ml final volume with potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8) containing 250 mM MgCl2 and 8 mM NADP; the reaction was started by the addition of 100 mM isocitrate (pH 7) and was followed by incubation at 30°C (28). One ICDH unit was defined as the amount of protein that produced an increase of 0.00622 U in absorbance measured at 340 nm per min of incubation and per mg of protein (13).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The sip individual mutations are not essential and do not affect the synthesis of the nonmutated SPases.

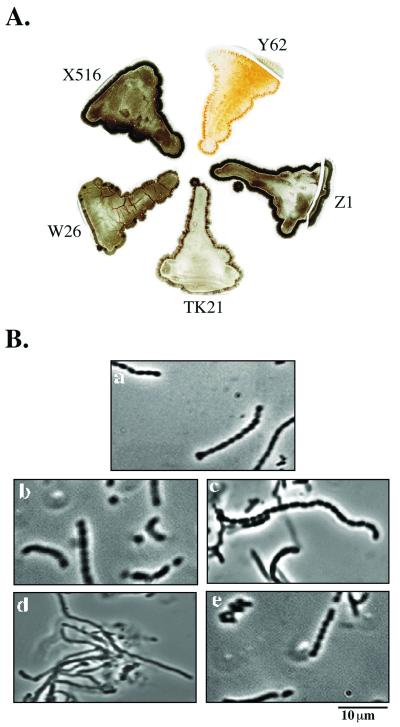

None of the mutated genes (S. lividans TK21W26, S. lividans TK21X516, S. lividans TK21Y62, and S. lividans TK21Z1) were shown to be essential for bacterial growth; mutant strain S. lividans TK21Y62 showed a delayed sporulation phenotype with a whitish aerial mycelium on an orange substrate mycelium in contrast to the typical dark gray color of the properly sporulated wild-type strain and the remaining mutant strains when cultured in solid R5 medium (Fig. 2A). S. lividans TK21Y62 also showed an altered mycelium morphology when grown in minimal solid medium, as visualized by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Sporulation of sip mutants. (A) Mycelium pigmentation of S. lividans TK21, S. lividans W26, S. lividans X516, S. lividans Y62, and S. lividans Z1 strains grown in R5 plates. (B) Phase-contrast microscopy of aerial hyphae from S. lividans TK21 (a), S. lividans W26 (b), S. lividans X516 (c), S. lividans Y62 (d), and S. lividans Z1 (e).

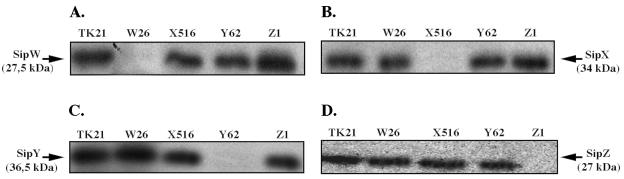

Western blot analysis was carried out to identify the sip gene products and to investigate whether the different mutations affected the synthesis of the nonmutated SPases, particularly those forming part of an operon. Submerged cultures of S. lividans TK21, S. lividans TK21W26, S. lividans TK21X516, S. lividans TK21Y42, or S. lividans TK21Z1 were incubated at 30°C in NMMP medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) mannitol as carbon source. They grew exponentially with a doubling time of ca. 4.2 h. The transition to stationary phase occurred at 25 to 30 h after inoculation at biomass dry weights of ca. 2.5 mg/ml. Cell-associated proteins were separated by SDS-12.5% PAGE; transferred to Immobilon-P membranes; incubated with antibodies raised against SipW, SipX, SipY, and SipZ; and visualized with 125I-labeled protein A as described in Materials and Methods. The results showed specific protein bands reacting with each antibody with relative molecular masses of 27.5, 34, 36.5, and 27 kDa for SipW, SipX, SipY, and SipZ, respectively, in accordance with theoretical molecular masses of 27.6, 34.5, 35.8, and 26.5 kDa for SipW, SipX, SipY, and SipZ, respectively (26). All sip mutant strains were able to express the remaining intact sip genes, as deduced from the specific protein bands obtained with antibodies to the nondeleted proteins (Fig. 3). Disruption of the sipW or sipX gene did not result in polar effects on the expression of the genes located downstream of the sip operon due to the absence of a transcription terminator at the end of the tsr gene that was inserted in the construction of these two mutants so that the transcription could follow through tsr to terminate at the end of the operon.

FIG. 3.

Sip proteins present in the sip mutant strains. The different SPases present in S. lividans wild-type and the different sip mutant strain cell cultures after 36 h of growth in NMMP medium were analyzed by Western blotting, with antibodies raised against SipW (A), SipX (B), SipY(C), and SipZ (D).

Effect of sip depletion on overall secretion.

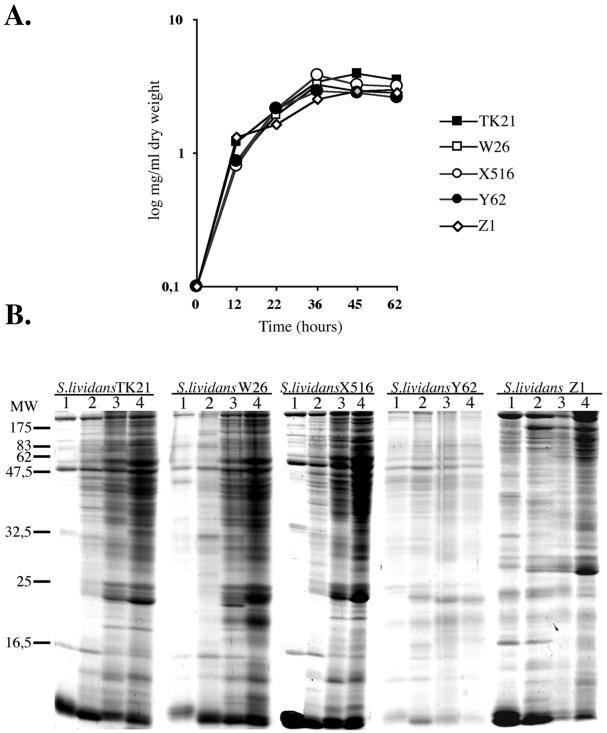

To check the effect of the different sip mutations on the extracellular protein secretion pattern, S. lividans TK21, S. lividans TK21W26, S. lividans TK21X516, S. lividans TK21Y42, or S. lividans TK21Z1 was incubated at 30°C in NMMP medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) mannitol as the carbon source, and the total extracellular proteins from culture broths were separated by SDS-15% PAGE. Although no significant differences in the growth of the bacterial cell cultures were observed (Fig. 4A), the accumulation of extracellular proteins in the S. lividans TK21Y62 culture was severely diminished compared to that in the other bacterial cell cultures (Fig. 4B). The total extracellular protease activity was determined, and the presence of the extracellular subtilisin inhibitor was monitored in all cases. All mutants showed a reduced accumulated extracellular protease activity in comparison to that of the wild type (ca. 15, 30, and 45% for sipX, sipZ, and sipW mutants, respectively), with SipY inactivation having the strongest effect, thus causing extracellular protease activity to fall below detection limits. No great differences were observed upon secretion of the subtilisin inhibitor between the wild type (S. lividans TK21) and the different sip mutants, except for the sipY mutant (Fig. 5), as determined by measuring the subtilisin activity remaining after incubation with the corresponding extracellular protein extracts, thereby confirming the observed diminished secretory capacity of the sipY mutant (Fig. 4B), as well as strongly suggesting that SipY plays a major role in protein secretion. The measured extracellular ICDH activity appeared to be very small compared to the respective intracellular activity in all cases, clearly indicating that the accumulation of extracellular proteins at the late phases of growth (Fig. 4B) was not due to lysis of the bacterial cell cultures (not shown).

FIG. 4.

Overall secretion pattern of S. lividans sip mutant strains. (A) Growth in NMMP of the wild-type and the different mutant strain cell cultures. (B) Total extracellular proteins present in S. lividans TK21, S. lividans W26, S. lividans X516, S. lividans Y62, and S. lividans Z1 cell cultures grown in NMMP after 12 h (1), 22 h (2), 36 h (3), and 45 h (4) of growth were analyzed by SDS-15% PAGE.

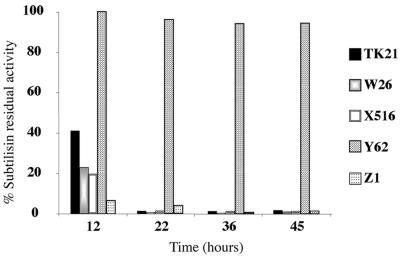

FIG. 5.

Extracellular enzyme activities. The subtilisin inhibitor activities present in bacterial cell cultures of S. lividans TK21, S. lividans W26, S. lividans X516, S. lividans Y62, and S. lividans Z1 strains grown in NMMP medium are shown. Subtilisin inhibitor activity is shown as a percentage of residual subtilisin activity under assay conditions.

Effect of sip depletion on agarase overproduction.

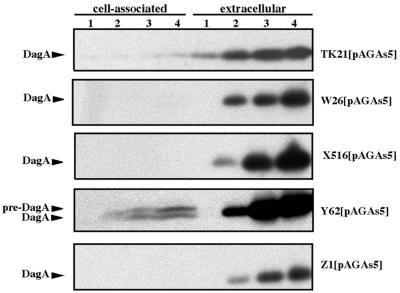

In order to correlate the secretion defect of the sipY mutant strain with a defect in the processing of preproteins, recombinant plasmid pAGAs5 containing the S. coelicolor dagA gene was propagated in S. lividans TK21 and in the different sip mutant strains. DagA synthesis was monitored by Western blotting with anti-DagA serum. No cell-associated agarase was detected in the wild-type strain or in the sipW, sipX, and sipZ mutant strains, whereas pre-DagA and mature-cell-associated agarase were clearly detected in the sipY mutant strain (Fig. 6), thus not only showing that sipY depletion confers a major defect in preprotein processing to the cell but also indicating that the remaining SPases could compensate for the deficiency, allowing secretion of the overproduced agarase.

FIG. 6.

Agarase secretion pattern of S. lividans sip mutant strains. Cell-associated and extracellular pre-agarase and mature agarase present in S. lividans wild-type and different sip mutant strain cell cultures grown in NMMP after 12 h (lane 1), 22 h (lane 2), 36 h (lane 3), and 45 h (lane 4) of growth were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies raised against DagA.

The construction of different combinations of the possible mutants is needed in order to obtain a further insight into the study of compensatory effects among the different sip genes and to confirm whether any combination of mutations that includes sipY may become essential. Thus far, the construction of double mutants containing a sipY mutation has not been possible, and attempts to produce a quadruple mutant have failed as well.

In the released sequence of the S. coelicolor genome, a putative fifth incomplete sip gene has been annotated in which the coding sequence for one of the transmembrane anchor domains is missing. The existence of a fifth sip gene in the S. lividans genome cannot be ruled out, although our attempts at finding this gene by screening of S. lividans genomic libraries have always produced negative results.

B. subtilis SipW is required for the efficient processing of the precursor of a spore-associated protein, pre-TasA (28). Apart from the specific activity of SipW, all B. subtilis Sip proteins apparently have overlapping substrate specificities (30, 31). From the results obtained it can be concluded that individual mutations in the different S. lividans sip genes, except for sipY, do not seem to have a severe effect on protein secretion, probably because of the compensatory effects of the minor SPases. Due to this compensatory effect, double and triple mutants of the sip genes need to be produced in order to assess substrate specificity for the different Sip proteins and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, coupled with mass spectrometry, is needed to identify the differences in extracellular protein patterns between S. lividans TK21 and the different sip mutant strains.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants BIO97-0650-C02-01 and BIO2000-0907 from the Spanish CICYT and by European Union grant QLK3-2000-00122. N.G. is a fellow of the IWT.

A.P. and V.P. contributed equally to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anné, J., and L. Van Mellaert. 1993. Streptomyces lividans as a host for heterologous protein production. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 114:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binnie, C., J. D. Cossar, and D. I. Stewart. 1997. Heterologous biopharmaceutical protein expression in Streptomyces. Trends Biotechnol. 15:315-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Böhni, P. C., R. J. Deshaies, and R. W. Schekman. 1988. SEC11 is required for signal peptide processing and yeast cell growth. J. Cell Biol. 106:1035-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chater, K. F. 1972. A morphological and genetic mapping study of white colony mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Gen. Microbiol. 72:9-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chater, K. F. 1998. Taking a genetic scalpel to the Streptomyces colony. Microbiology 144:1465-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cregg, K. M., I. Wilding, and M. T. Black. 1996. Molecular cloning and expression of the spsB gene encoding an essential type I signal peptidase from Staphylococus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178:5712-5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalbey, R. E., and W. Wickner. 1985. Leader peptidase catalyzes the release of exported proteins from the outer surface of the Escherichia coli plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 260:15925-15931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalbey, R. E., M. O. Lively, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1997. The chemistry and enzymology of the type I signal peptidases. Protein Sci. 6:1129-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar, B. S., and E. D. Schwoebel. 1990. Preparation of polyclonal antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 182:663-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geukens, N., V. Parro, L. Rivas, R. P. Mellado, and J. Anné. 2001. Functional analysis of the Streptomyces lividans type I signal peptidases. Arch. Microbiol. 176:377-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert, M., R. Morosoli, F. Shareck, and D. Kluepfel. 1995. Production and secretion of proteins by streptomycetes. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 15:13-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harwood, C. R., and S. M. Cutting. 1990. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., Chichester, England, United Kingdom.

- 14.Hoang, V., and J. Hofemeister. 1995. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens possesses a second type I signal peptidase with extensive sequence similarity to other Bacillus SPases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1269:64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood, D. A., M. J. Bibb, K. F. Chater, H. M. Kieser, D. J. Lydiate, C. P. Smith, J. M. Ward, and H. Schrempf. 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 16.Kaneko, T., S. Sato, H. Kotani, A. Tanaka, E. Asamizu, Y. Nakamura, N. Miyajima, M. Hirosawa, M. Sugiura, S. Sasamoto, T. Kimura, T. Hosouchi, A. Matsuno, A. Muraki, N. Nakazaki, K. Naruo, S. Okumura, S. Shimpo, C. Takeuchi, T. Wada, A. Watanabe, M. Yamada, and S. Yasuda Mand Tabata. 1996. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions (supplement). DNA Res. 3:185-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klenk, H. P., R. A. Clayton, J. F. Tomb, O. White, K. E. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, R. J. Dodson, M. Gwinn, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, D. L. Richardson, A. R. Kerlavage, D. E. Graham, N. C. Kyrpides, R. D. Fleischmann, J. Quackenbush, N. H. Lee, G. G. Sutton, S. Gill, E. F. Kirkness, B. A. Dougherty, K. McKenney, M. D. Adams, B. Loftus, J. C. Venter, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature 390:364-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojima, S., I. Kumagai, and K. Miura. 1990. Effect of inhibitory activity of mutation at reaction site P4 of the Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor, SSI. Protein Eng. 3:527-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lammertyn, E., L. Van Mellaert, S. Schacht, C. Dillen, E. Sablon, A. Van Broekhoven, and J. Anné. 1997. Evaluation of a novel subtilisin inhibitor gene and mutant derivatives for the expression and secretion of mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha by Streptomyces lividans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1808-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacNeil, D. J., K. M. Gewain, C. L. Ruby, G. Dezeny, P. H. Gibbons, and T. MacNeil. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meijer, W. J., A. de Jong, G. Bea, A. Wisman, H. Tjalsma, G. Venema, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1995. The endogenous Bacillus subtilis (natto) plasmids pTA1015 and pTA1040 contain signal peptidase-encoding genes: identification of a new structural module on cryptic plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 17:621-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray, N. E. 1983. Phage lambda and molecular cloning, p. 398-432. In R. W. Hendrix et al. (ed.), Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Muth, G., B. Nussbaumer, W. Wohlleben, and A. Pühler. 1989. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219:341-348. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parro, V., and R. P. Mellado. 1994. Effect of glucose on agarase overproduction by Streptomyces. Gene 145:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parro, V., S. Schacht, J. Anne, and R. P. Mellado. 1999. Four genes encoding different type I signal peptidases are organized in a cluster in Streptomyces lividans TK21. Microbiology 145:2255-2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Stöver, A. G., and A. Driks. 1999. Control of synthesis and secretion of the Bacillus subtilis protein YqxM. J. Bacteriol. 181:7065-7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timmons, T. M., and B. S. Dunbar. 1990. Protein blotting and immunodetection. Methods Enzymol. 182:679-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tjalsma, H., A. Bolhuis, M. L. van Roosmalen, T. Wiegert, W. Schumann, C. P. Broekhizen, W. J. Quax, G. Venema, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1998. Functional analysis of the secretory precursor processing machinery of Bacillus subtilis: identification of a eubacterial homolog of archaeal and eukaryotic signal peptidases. Genes Dev. 12:2318-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tjalsma, H., M. A. Noback, S. Bron, G. Venema, K. Yamane, and J. M. van Dijl. 1997. Bacillus subtilis contains four closely related type I signal peptidases with overlapping substrate specificities: constitutive and temporally controlled expression of different sip genes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25983-25992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschantz, W. R., M. Sung, V. M. Delgado-Partin, and R. Dalbey. 1993. A serine and a lysine residue implicated in the catalytic mechanisms of the Escherichia coli leader peptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:27349-27354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dijl, J. M., A. de Jong, G. Venema, and S. Bron. 1995. Identification of the potential active site of the SPase SipS of Bacillus subtilis: structural and functional similarities with LexA-like proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3611-3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Mellaert, L., and J. Anné. 1994. Protein secretion in gram-positive bacteria with high GC-content. Recent Res. Dev. Microbiol. 3:324-340. [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Heijne, G. 1990. The signal peptide. J. Membr. Biol. 115:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White, O., J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, M. L. Gwinn, W. C. Nelson, D. L. Richardson, K. S. Moffat, H. Qin, L. Jiang, W. Pamphile, M. Crosby, M. Shen, J. J. Vamathevan, P. Lam, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, C. Zalewski, K. S. Makarova, L. Aravind, M. J. Daly, C. M. Fraser, et al. 1999. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococus radiodurans R1. Science 286:1571-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]