Abstract

Bacteriophage lambda site-specific recombination comprises two overall reactions, integration into and excision from the host chromosome. Lambda integrase (Int) carries out both reactions. During excision, excisionase (Xis) helps Int to bind DNA and introduces a bend in the DNA that facilitates formation of the proper excisive nucleoprotein complex. The carboxyl-terminal α-helix of Xis is thought to interact with Int through direct protein-protein interactions. In this study, we used gel mobility shift assays to show that the amino-terminal domain of Int maintained cooperative interactions with Xis. This finding indicates that the amino-terminal arm-type DNA binding domain of Int interacts with Xis.

The site-specific recombination system encoded by bacteriophage lambda provides a classic example of a reaction controlled by a higher-order multiple-protein-DNA complex. The lambda recombination complex is composed of specific DNA sites in the phage and bacterial chromosomes and utilizes host-encoded and phage-encoded proteins (for a review, see reference 1). Integrative recombination between specific attachment sites, attP on the phage DNA and attB on the bacterial chromosome, generates recombinant attR and attL sites flanking the prophage DNA. Both reactions are catalyzed by the phage-encoded protein integrase (Int) and are assisted by accessory proteins. The host-encoded integration host factor is required for both reactions. Excision requires an additional phage-encoded protein called excisionase (Xis). Excision is stimulated by the factor for inversion stimulation, which is supplied by the host (19).

Int plays a central role in recombination. To carry out the cleavage, strand exchange, and resealing of the DNA attachment site, Int recognizes two distinct DNA sequences (16, 17). The two classes of Int binding sequences are called core-type and arm-type sites. The core-type sites consist of imperfect inverted repeats that flank the sites of strand exchange during recombination. Five arm-type sites occur outside the region of strand exchange on attP, attR, and attL. Three contiguous sites called P′1, P′2, and P′3 are located on attP and attL. Two sites called P1 and P2 are both on attP and on attR.

Int protein has three major domains. The amino-terminal 64 amino acids consist of the arm-type DNA binding domain (13). A second domain spanning amino acid residues 65 to 169 involves core-type binding (21). The third domain includes amino acid residues 170 to 356 (10). The C-terminal region contains the catalytic domain in which the conserved amino acids required for type I topoisomerase activity reside.

Although both integration and excision reactions are carried out by Int, excision is not a simple reversion of integration. The direction of recombination is determined, in part, by the amount of Xis present in the cell (6, 22). Xis recognizes two direct, imperfect, 13-bp repeats, designated X1 and X2, which are located between the P2 site and the core site on attR (Fig. 1) (20, 26). The P2 site binds Int weakly and is required only for excisive recombination (2, 14). Binding of Xis to X1 and X2 introduces a bend in the DNA and promotes the binding of Int to the P2 site to help form the attR nucleoprotein complex (3, 15).

FIG. 1.

Organization of the Int and Xis binding sites on attR. The attR site contains a single Int arm-type site (P2) and two Xis binding sites (X1 and X2) that are required for excisive recombination. The X1 and X2 sites are arranged as direct repeats.

Mutational analyses of the xis gene indicate that the carboxyl-terminal region is in direct contact with Int (15, 25). A C-terminal truncated Xis protein consisting of 53 of the total 72 amino acids continues to bind specifically to the Xis binding sites but loses the ability to interact cooperatively with Int (15). Mutants on one surface of the putative α-helix spanning amino acid residues 59 to 65 fail to interact cooperatively with Int, suggesting that this α-helical surface interacts with Int (25). The purpose of this study was to localize the regions in the Int protein that interact with Xis.

The amino-terminal domain of Int interacts with Xis.

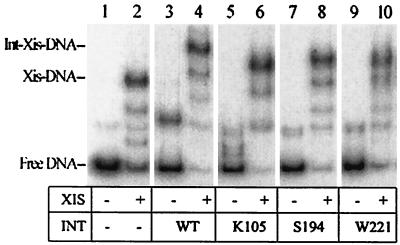

To identify the target region of Int that interacts with Xis protein, we used a series of truncated Int mutant proteins and performed gel shift assays in vitro to test cooperative interactions between Int and Xis. We chose three mutant proteins with nonsense mutations at positions K105, S194, and W221 (7). The mutant Int proteins and the wild-type Int protein were expressed from corresponding plasmid pSX1-2 derivatives (11) in a suppressor-free Escherichia coli strain (JG1199) containing null mutations in ihfA and ihfB. The Int proteins were partially purified on phosphocellulose as described by Jessop et al. (8). The DNA binding activity as well as the cooperative interaction of Int and Xis was measured by gel shift assays as described previously (5). The DNA fragment used in the binding reactions contained the P2, X1, and X2 sites (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows the results of a gel shift assay with the wild-type and truncated Int proteins in the presence and absence of Xis. The Xis used contained an N-terminal His tag. Previous studies with the His-tagged protein showed that it was indistinguishable from the wild-type protein with respect to its ability to promote excisive recombination, to bind DNA, and to interact cooperatively with the factor for inversion stimulation (5). Lane 2 contains an assay mixture with a concentration of Xis sufficient to shift a large portion of the DNA. Bushman et al. (3) showed previously that the band of lowest mobility contained Xis monomers bound to the X1 and X2 sites. They also observed two bands of intermediate mobility that were interpreted to be monomers bound to a single site. At the concentration used in the assay, Int protein itself did not bind strongly to the P2 site (Fig. 2, lane 3). However, when the amount of Xis used in the assay mixture in lane 2 was added to the same amount of Int, almost all of the DNA formed Int-Xis-DNA complexes that migrated more slowly than the Xis-DNA complex (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 and 4). The three nonsense mutant proteins of Int, those with mutations at K105, S194, and W221, formed small amounts of complex with the P2 site at the protein concentrations used (Fig. 2, lanes 5, 7, and 9). The complexes had a greater mobility than the complex containing wild-type Int, suggesting that the complexes contain truncated Int. Addition of Xis at the concentration used in the assay mixture in lane 2 facilitated binding of these truncated Int proteins to the P2 site, leading to the production of slowly migrating Int-Xis-DNA complexes (Fig. 2, lanes 6, 8, and 10). These results indicate that even the smallest protein, consisting of 104 amino acids, interacts cooperatively with Xis in binding to the P2 site.

FIG. 2.

Cooperative DNA binding of Xis and truncated Int mutant proteins. The 32P-labeled attR DNA fragments were amplified from a P22 challenge phage, P22xis4B, containing P2, X1, and X2 sites (15). Xis protein was histidine tagged and was purified as described previously (5). The wild-type (WT) and mutant Int proteins were partially purified from suppressor-free and integration host factor-deficient E. coli strain JG1199 using phosphocellulose resin as described by Jessop et al. (8). Aliquots of labeled DNA and proteins were incubated in binding buffer (44 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 11 mM borate, 1.25 mM EDTA, 40 mM KCl, 0.5 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 10% glycerol) at room temperature for 30 min. One microliter of Int protein and 1 μl of Xis protein were added as indicated. As a nonspecific competitor, 0.5 μg of sonicated calf thymus DNA was added, and the final reaction volumes were 10 μl. After the components were separated by electrophoresis in 5% polyacrylamide gels at room temperature, the gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography.

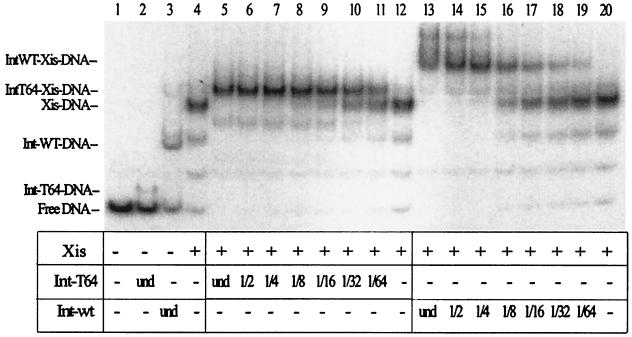

An N-terminal fragment containing the first 64 amino acid residues of Int binds arm sites with high affinity (13, 24). We performed a gel shift assay using a fragment of Int, called Int-T64, which contains the amino-terminal 63 amino acids, to determine if it interacts with Xis (Fig. 3). At the concentration of the Int-T64 fragment tested, only a small portion of the attR DNA was shifted (Fig. 3, lane 2). At the concentrations of wild-type Int and Xis used, a larger fraction of attR was shifted (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). When serial dilutions of Int were added to reaction mixtures containing the same amount of Xis employed in lane 3, Int and Xis bound cooperatively to the attR DNA (Fig. 3, lanes 13 to 20), in agreement with previous results (3, 15). As the concentration of Int was diluted, the Int-Xis DNA complexes disappeared and Xis-DNA complexes were formed. When serial dilutions of the Int-T64 fragment were used, it was evident that it also bound cooperatively with Xis (Fig. 3, lanes 5 to 12). Int-T64 concentrations ranging from undiluted to 1/16 formed complexes with Xis and shifted all of the attR DNA. In contrast, undiluted Int-T64 by itself formed a small fraction of complex with attR. As the concentrations of the T64 fragment decreased, the Xis-DNA complexes appeared (Fig. 3, lanes 16 to 20). The results clearly show that the Xis protein facilitates binding of the T64 fragment to the P2 site.

FIG. 3.

Xis protein helps the Int-T64 mutant protein bind to P2. One microliter of Xis (0.36 μg) and 1 μl of one of the indicated dilutions of wild-type Int or the Int-T64 fragment were added to the reaction mixtures as indicated. The undiluted (und) wild-type (WT) Int protein concentration was approximately 0.4 μg/μl, and the concentration of Int-T64 was approximately 0.1 μg/μl. The incubation conditions and gel composition were the same as those described for Fig. 2.

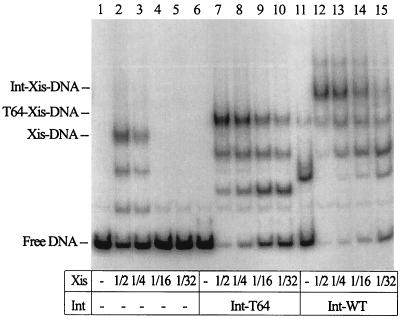

Figure 4 shows another experiment, where the concentrations of wild-type Int and the Int-T64 fragment were held constant and the amount of Xis was varied. At the highest concentration of Xis used, about one-half or less of the DNA was shifted into an Xis-DNA complex. At the lower concentrations of Xis, no detectible complex was formed (Fig. 4, lanes 2 to 5). However, when either the Int-T64 fragment or wild-type Int was added to the reaction mixtures, much more DNA was shifted to form Int-Xis-DNA or Int-T64-Xis-DNA complexes (Fig. 4, lanes 7 to 10 and 11 to 15). These results also indicate that the Int-T64 fragment binds cooperatively with Xis. Taken together, the results displayed in Fig. 3 and 4 show that the fragment containing the amino-terminal 63 amino acids of Int, which defines the arm-type DNA binding domain, interacted cooperatively with Xis in binding the P2 DNA site. Thus, a significant portion if not the entire surface of Int that interacts with Xis must reside in the amino-terminal domain of Int.

FIG. 4.

The mutant protein Int-T64 helps Xis bind DNA. One microliter of wild-type (WT) Int (0.4 μg/μl) or the Int-T64 fragment (0.1 μg/μl) and 1 μl of one of the indicated dilutions of Xis were added to the reaction mixtures as indicated. The undiluted concentration of Xis was 0.36 μg/μl. The incubation conditions and gel composition were the same as those described for Fig. 2.

Multiple roles of the Int arm-type DNA binding domain.

Until recently, a relatively simple model was proposed for the biological function of the amino-terminal domain of the lambda Int. The high-affinity amino-terminal domain binds to the arm-type sequence to deliver the low-affinity core-binding domain of Int to the core-type site, where actual cleavage and rejoining occur (9, 12, 13). Simultaneous binding to the two different DNA sites by a single Int molecule is further facilitated by accessory proteins that bind and bend the sites between the arm-type and the core-type sequences (9, 13).

Several recent studies, however, revealed more elaborate roles of the amino-terminal domain of the Int protein in addition to the architectural role. The amino-terminal domain is implicated as a region involved in protein-protein interactions between Int molecules during intasome formation (8). Some amino acid substitutions in one domain may alter the structure of the other domain through domain-domain communication. A few amino acid substitutions in the HK022 Int protein that relax core-binding specificity without changing arm-type binding affinity are located in the arm-type binding domain, within the region that is completely conserved between the HK022 and lambda Int proteins (4). A class of mutant proteins with amino acid substitutions in the core-binding domain that also affect arm-type binding has also been reported (7). In addition, when the amino-terminal domain of Int is added separately to the carboxyl domain (amino acids 65 to 356), core-DNA binding and cleavage are stimulated. In contrast, the amino-terminal domain of the full-length protein inhibits core binding and DNA cleavage (18). Therefore, the amino-terminal domain of Int plays a role in modulating the activity of core-binding and catalytic domains.

Recently, the structure of the amino-terminal domain containing the first 64 amino acid residues of Int was solved with nuclear magnetic resonance by Wojciak et al. (24). The domain is related structurally to the N-terminal domain of the Tn916 integrase (23). Modeling of the structure and a mutational analysis indicated that Arg4, Arg5, Arg27, and Glu34 of the fragment are involved in binding arm-type sites. Interestingly, the structure shows that three isoleucine residues (Ile45, Ile49, and Ile53) are solvent exposed. As noted by Wojciak et al. (24), these residues may form the surface of an Int protein that interacts with other Int molecules.

In this study, we showed that the amino-terminal arm-type DNA binding domain of Int interacts cooperatively with Xis. Thus, the amino-terminal domain also functions in regulating directionality of recombination by interacting with Xis directly. This result, along with the other recent findings described, suggests that the amino-terminal domain of lambda Int has multiple functions that include DNA binding, interactions with Xis, and modulation of integrase function. Int is an exquisitely evolved protein: it binds to two distinct DNA sites and communicates through protein-protein interactions with itself and with Xis to ensure biologically useful direction of the recombination reaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grant GM 28717 and KOSEF grant R04-2001-00178 from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation.

We thank Maria MacWilliams for help with the plasmid constructions, Aras Mattis for comments on the manuscript, and members of the R. I. Gumport and J. F. Gardner laboratories for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azaro, M. A., and A. Landy. 2002. The integration/excision cycle of λ and other bacteriophages, p. 118-148. In N. L. Craig et al. (ed.), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Bauer, C. E., S. D. Hesse, R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1986. Mutational analysis of integrase arm type binding sites of bacteriophage lambda. J. Mol. Biol. 121:179-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushman, W., S. Yin, L. Thio, and A. Landy. 1984. Determinants of directionality in lambda site-specific recombination. Cell 39:699-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, Q., B. M. Swalla, M. Beck, R. Alcaraz, Jr., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 2000. Specificity determinants for bacteriophage Hong Kong 022 integrase: analysis of mutants with relaxed core-binding specificities. Mol. Microbiol. 36:424-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho, E. H., R. Alcaraz, Jr., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 2000. Characterization of bacteriophage lambda excisionase mutants defective in DNA binding. J. Bacteriol. 182:5807-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echols, H., and G. Guarneros. 1983. Control of integration and excision, p. 75-93. In R. Hendrix, J. Roberts, F. Stahl, and R. Weisberg (ed.), Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 7.Han, Y. W., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1994. Mapping the functional domains of bacteriophage lambda integrase protein. J. Mol. Biol. 235:908-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessop, L., T. Bankhead, D. Wong, and A. M. Segall. 2000. The amino terminus of bacteriophage λ integrase is involved in protein-protein interactions during recombination. J. Bacteriol. 182:1024-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, S., and A. Landy. 1992. Lambda Int protein bridges between higher order complex at two distant chromosomal loci attL and attR. Science 256:198-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon, H. J., R. Tirumalai, A. Landy, and T. Ellenberger. 1997. Flexibility in DNA recombination: structure of the integrase catalytic core. Science 276:126-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, E., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1990. Genetic analysis of bacteriophage λ integrase interactions with arm-type attachment site sequences. J. Bacteriol. 172:1529-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moitoso de Vargas, L., C. A. Pargellis, N. M. Hasan, E. W. Bushman, and A. Landy. 1988. Autonomous DNA binding domain of λ integrase recognize different sequence families. Cell 54:923-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moitoso de Vargas, L., S. Kim, and A. Landy. 1989. DNA looping generated by DNA bending protein IHF and the two domains of lambda integrase. Science 244:1457-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Numrych, T. E., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1990. A comparison of the effects of single-base and triple-base changes in the integrase arm-type binding sites on the site-specific recombination of bacteriophage lambda. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3953-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numrych, T. E., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1992. Characterization of the bacteriophage lambda excisionase (Xis) protein: the C terminus is required for Xis-integrase cooperativity but not for DNA binding. EMBO J. 11:3797-3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross, W., and A. Landy. 1982. Bacteriophage λ Int protein recognizes two classes of sequence in the phage att site: characterization of arm-type sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:7724-7728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross, W., and A. Landy. 1983. Patterns of λ Int recognition on the regions of strand exchange. Cell 33:261-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar, D., M. Radman-Livaja, and A. Landy. 2001. The small DNA binding domain of Int is a context-sensitive modulator of recombinase functions. EMBO J. 20:1203-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson, J. F., L. Moitoso de Vargas, C. Koch, R. Kahmann, and A. Landy. 1987. Cellular factors couple recombination with growth phase: characterization of a new component in the λ site-specific recombination pathway. Cell 50:901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson, J. F., L. Moitoso de Vargas, S. Skinner, and A. Landy. 1987. Protein-protein interactions in a higher-order structure direct lambda site-specific recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 195:481-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tirumalai, R. S., H. J. Kwon, E. H. Cardente, T. Ellenberger, and A. Landy. 1998. The recognition of core-type DNA sites by λ integrase. J. Mol. Biol. 279:513-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisberg, R. A., and M. E. Gottesman. 1971. The stability of Int and Xis functions, p. 489-500. In A. D. Hershey (ed.), The bacteriophage Lambda. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Wojciak, J. M., K. M. Connolly, and R. T. Clubb. 1999. NMR structure of the Tn916 integrase-DNA complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:366-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wojciak, J. M., D. Sakar, A. Landy, and R. T. Clubb. 2002. Arm-site binding by λ integrase: solution structure and functional characterization of its amino-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3434-3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu, Z., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1998. Defining the structural and functional roles of the carboxyl region of the bacteriophage lambda excisionase (Xis) protein. J. Mol. Biol. 281:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin, S., W. Bushman, and A. Landy. 1985. Interaction of the lambda site-specific recombination protein Xis with attachment site DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1040-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]