Abstract

Bacillus subtilis ccpA mutant strains exhibit two distinct phenotypes: they are defective in catabolite repression, and their growth on minimal media is strongly impaired. This growth defect is largely due to a lack of expression of the gltAB operon. However, growth is impaired even in the presence of glutamate. Here, we demonstrate that the ccpA mutant strain needs methionine and the branched-chain amino acids for optimal growth. The control of expression of the ilv-leu operon by CcpA provides a novel regulatory link between carbon and amino acid metabolism.

Bacillus subtilis uses glucose and glutamine as preferred sources of carbon and nitrogen, respectively. While the control of both carbon and nitrogen metabolism has attracted much attention during the past years (for reviews, see references 2, 5, and 20), the regulatory interrelation between the two metabolic branches has been the subject of much less analysis. A key reaction in ammonia assimilation, the biosynthesis of glutamate, seems to be subject to double control by glutamate and glucose for B. subtilis. This regulation involves specific and general regulators, GltC and CcpA, respectively (1, 3).

CcpA was discovered as a factor mediating carbon catabolite repression of many genes in B. subtilis (2, 9, 20). Moreover, CcpA is required as a positive regulator for the expression of genes encoding enzymes of glycolysis, overflow metabolism, and ammonia assimilation (3, 4, 23). In the presence of glucose or other well-metabolizable carbon sources, CcpA can bind its target sites (catabolite responsive elements [cre]) in the control regions of the regulated genes and repress or activate transcription. To bind DNA, CcpA needs to form a complex with either of two cofactors, the HPr protein of the phosphotransferase system or its regulatory paralogue, Crh (6, 7).

In addition to its role as a transcriptional regulator, CcpA is involved in growth control. On minimal media, B. subtilis ccpA mutant strains exhibit a severe growth defect (12, 16, 24). This defect is most obvious on minimal media with glucose and ammonia as single sources of carbon and nitrogen, respectively. This was attributed to the lack of expression of the gltAB operon encoding glutamate synthase in the ccpA mutant (3). However, the molecular details of this regulation are not yet understood.

In this work, we describe experiments aimed at the identification of CcpA-dependent cellular functions that result in the growth defect of ccpA mutants. Among the amino acids present in caseine hydrolysate, we identified methionine and the branched-chain amino acids as important for growth of ccpA mutant strains in minimal media. The requirement for branched-chain amino acids results from a decreased expression of the biosynthetic ilv-leu operon in the ccpA mutant and can be bypassed by expression of this operon from an inducible promoter.

Identification of a chemically defined medium which supports fast growth of a ccpA mutant strain.

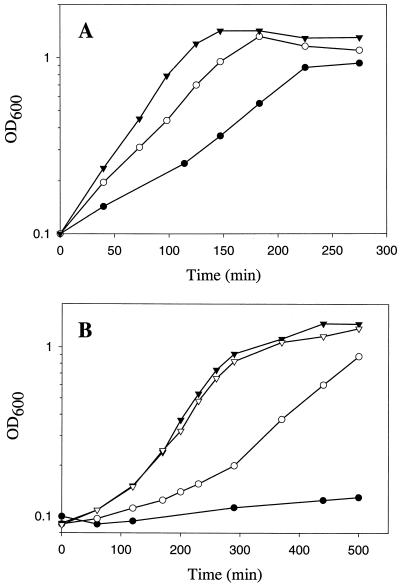

Severe growth defects of B. subtilis ccpA mutants were observed in minimal media. Even in the presence of glutamate and glucose, the growth rate of the ccpA mutant is lower than that of wild-type strains (12). We attempted therefore to identify the factor(s) that is required to allow a growth rate of the ccpA mutant comparable to that of wild-type strains. The wild-type B. subtilis strain QB7144 (7) and its isogenic ΔccpA57 derivative, GP300 (13), were grown in C minimal medium containing glucose (C-Glc) (15) in the absence or presence of glutamate (0.8%, wt/vol) and caseine hydrolysate (0.1%, wt/vol), respectively. The wild-type strain grew under all conditions tested (Fig. 1A). However, the addition of amino acids as a nitrogen source (CE-Glc, CE-Glc-CAA) resulted in faster growth than was observed with a medium containing ammonia as a single source of nitrogen (C-Glc). In contrast, the ccpA mutant strain GP300 did not grow in the presence of glucose as a single source of carbon and ammonia as a single source of nitrogen (Fig. 1B). The addition of glutamate (CE-Glc) restored growth of the ccpA mutant strain, but not to the rate seen for the wild-type strain. The addition of caseine hydrolysate to CE-Glc medium resulted in a further increase of the growth rate (Fig. 1B). The generation times in CE-Glc containing CAA were determined to be 37 and 47 min for the wild-type and ccpA mutant strains, respectively. Thus, one or more components that are present in caseine hydrolysate enable the ccpA mutant to grow nearly as fast as the wild-type strain.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of the growth deficiency of a B. subtilis ccpA mutant. The growth of the wild-type strain QB7144 (A) and that of the ccpA mutant strain GP300 (B) were monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Cultures were grown at 37°C under vigorous agitation in C-Glc (•), CE-Glc (○), CE-Glc-CAA (▾), and CE-Glc supplemented with a synthetic amino acid mixture that mimics the CAA solution (▿).

The main components of caseine hydrolysate are amino acids. As observed with caseine hydrolysate, a synthetic mixture of amino acids (14) allowed the ccpA mutant to grow as fast as the wild-type strain if added to CE-Glc medium (Fig. 1B). This finding had two implications: first, it demonstrated that the amino acids really were required for rapid growth of the ccpA mutant strain, and second, this was the first chemically defined medium in which a ccpA mutant did not exhibit any growth defect.

Identification of a minimal set of amino acids that is required to support rapid growth of a ccpA mutant strain.

To identify individual amino acids that are important for growth of the ccpA mutant, we prepared five different substractive pools of amino acids in which two to five amino acids were omitted according to their biosynthetic pathways. The omission of amino acids of the aspartate family (aspartate, lysine, threonine, methionine, and isoleucine) or of branched-chain amino acids and alanine (valine, leucine, isoleucine, and alanine) resulted in slower growth than was observed with CE-Glc medium containing caseine hydrolysate (data not shown). Thus, one or more of the amino acids omitted in these two pools may be necessary for efficient growth of the ccpA mutant strain.

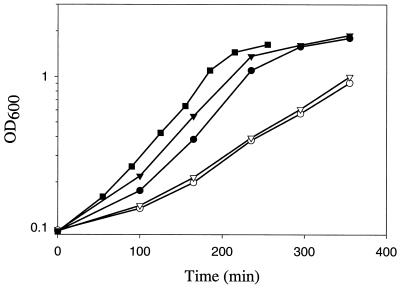

The amino acids that were omitted in the two pools are all derived from aspartate and pyruvate as biosynthetic precursors. Thus, the ccpA mutant could be defective in synthesizing these precursors or in the downstream biosynthetic pathway(s). To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested the effect of adding the precursors (aspartate and pyruvate) or of all the amino acids omitted in the two substractive pools (alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, aspartate, lysine, threonine, and methionine) to CE-Glc medium. While the addition of pyruvate and aspartate had no effect on growth of the ccpA mutant GP300, the amino acid mixture was as effective in supporting growth as the complete synthetic mixture of amino acids (Fig. 2). These data indicate that the amino acid biosynthetic pathways are not fully active in the ccpA mutant strain.

FIG. 2.

Identification of amino acids necessary for efficient growth of a ccpA mutant strain. Cultures of the ccpA mutant strain GP300 were grown at 37°C under vigorous agitation in CE-Glc (○), CE-Glc supplemented with a synthetic amino acid mixture that mimics the CAA solution (▾), CE-Glc supplemented with pyruvate and aspartate (each 0.1%, wt/vol) (▿), CE-Glc supplemented with amino acids of the aspartate family, branched chain amino acids, and alanine (•), and CE-Glc supplemented with valine (40 mg liter−1), leucine (50 mg liter−1), isoleucine (25 mg liter−1), and methionine (20 mg liter−1) (▪). Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

To define the amino acids required for growth of the ccpA mutant more precisely, we omitted individual amino acids from the mixture described above. These experiments identified a minimal mix composed of valine, leucine, isoleucine, and methionine as being required and sufficient to allow rapid growth of GP300 (Fig. 2). Thus, the biosyntheses of the branched-chain amino acids and of methionine may be defective in the ccpA mutant GP300.

Regulation of the ilv-leu operon by CcpA.

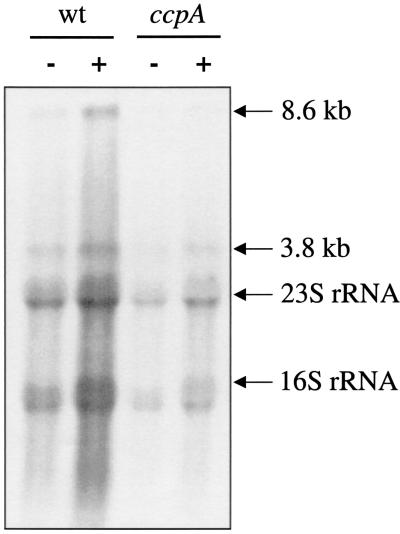

Three genetic loci are involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids in B. subtilis, the ilv-leu operon, the ilvA gene encoding threonine dehydratase, and the ilvD gene encoding dihydroxy acid dehydratase. First, we analyzed transcription of the ilv-leu operon and the presumable involvement of CcpA in the regulation of expression of the operon. RNA was isolated from the B. subtilis wild-type strain 168 and its isogenic ccpA derivative, GP302 (15) grown in CSE minimal medium (3) with or without glucose and subjected to a Northern blot analysis using a riboprobe specific for ilvB, the first gene of the ilv-leu operon. Two transcripts were observed in the wild-type strain, an 8.6-kb transcript corresponding to a heptacistronic mRNA encompassing all genes of the ilv-leu operon and a 3.8-kb transcript covering the three promoter-proximal genes, ilvB, ilvN, and ilvC. The amounts of both transcripts were increased in cells grown in the presence of glucose. In contrast, only basal levels that were not increased in the presence of glucose were detected in the ccpA mutant strain GP302 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Influence of a functional CcpA on expression of the ilv-leu operon. For Northern blot analysis, total RNA was isolated from B. subtilis 168 (wild type) and GP302 (ccpA) grown in CSE minimal medium in the absence (−) or presence (+) of glucose (0.5%, wt/vol). RNA was separated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% formaldehyde agarose gel. After blotting, the nylon membrane was hybridized to an ilvB-specific digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe. Five micrograms of RNA was applied per lane. Preparation of total RNA of B. subtilis and Northern blot analysis were carried out as described previously (15). The ilvB digoxigenin RNA probe was obtained by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics) using a PCR-generated fragment obtained with the primer pair HL61 (5′AATGTACACAGACGATGAGC) and HL62 (5′ CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAAAAATGTCTGCTTCCTGAAATG). The reverse primer contained a T7 RNA polymerase recognition sequence (underlined in HL62). The sizes of the transcripts corresponding to the full-length ilv-leu operon mRNA (8.6 kb) and ilvBNC (3.8 kb) are indicated. Note that the probe cross-hybridized with the 16S and 23S rRNAs. The sizes of 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA are indicated by arrows.

Control of the activity of the promoters of genes and operons involved in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis by glucose.

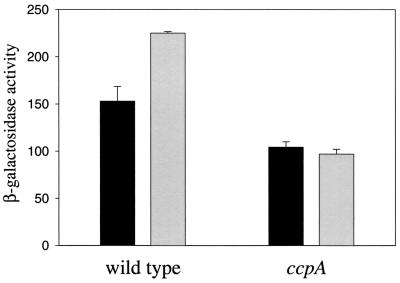

The data presented above demonstrate that CcpA is necessary for full expression of the ilv-leu operon. Next, we wished to study whether this control is exerted at the level of transcription initiation of the ilv-leu operon. Moreover, we asked if expression of ilvA and ilvD would also be under positive control of CcpA. A transcriptional fusion of an 848-bp fragment of the ilv-leu promoter region encompassing all known regulatory elements (8) to a promoterless lacZ gene was constructed using the plasmid pAC6 (21). The expression of this ilvB-lacZ fusion was analyzed in the wild type (GP339) and a ccpA mutant (GP341, constructed by transformation of GP339 with chromosomal DNA of BGW2 [ccpA::Tn917 erm [11]) strains after growth in CSE minimal medium in the presence or absence of caseine hydrolysate. While the promoter was fully active in the absence of caseine hydrolysate, a 10-fold repression was observed in the presence of caseine hydrolysate in both strains (data not shown). All further experiments were performed in the absence of caseine hydrolysate. To analyze the role of CcpA as a regulator involved in carbon control of gene expression, we determined the ilvB promoter activity after growth of the two strains in CSE with or without glucose (Fig. 4). As observed in Northern blot experiments, full promoter activity was found only in the presence of glucose in the medium. In contrast, the ccpA mutant strain GP341 exhibited a reduced ilvB promoter activity which was not increased in the presence of glucose. The effects caused by glucose or the ccpA mutation were rather weak; however, they were significant and relevant for the growth of the ccpA mutant strain.

FIG. 4.

Influence of a ccpA mutation on the promoter activity of an ilvB-lacZ fusion. B. subtilis strains GP339 (wild type) and GP341 (ccpA) carrying an ilvB-lacZ transcriptional fusion were grown in CSE medium with (grey bars) or without (black bars) glucose (0.5%, wt/vol). The β-galactosidase activities were measured in extracts prepared from exponentially growing cells (optical density at 600 nm, 0.6 to 0.8) and are expressed in units per milligram of protein. The values shown were derived from three independent measurements. Standard deviations are indicated.

Most of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids are encoded in the ilv-leu operon. The ilvA and ilvD genes are, however, not subject to any regulation by CcpA (our unpublished results).

Xylose-inducible expression of the ilv-leu operon in a ccpA mutant overcomes the requirement of branched-chain amino acids.

Our results indicate that the ilv-leu operon might be the only genetic locus involved in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis which depends on a functional CcpA for full expression. To test this hypothesis more rigorously, we constructed a strain which carries the ilv-leu operon under the control of a xylose-inducible promoter. Briefly, a 526-bp PCR fragment from 28 bp upstream to 498 bp downstream of the translational start codon of the ilvB gene was cloned into the plasmid pX2 (17) to yield pGP518. B. subtilis strain 168 was transformed with the plasmid pGP518, and the resulting strain, GP324, was able to grow only in CSE minimal medium in the presence of xylose (1.5%, wt/vol) or caseine hydrolysate (0.1%, wt/vol). Strain GP325 carrying a disrupted ccpA in addition to the xylose-inducible ilv-leu operon was constructed by transformation of GP324 with chromosomal DNA of QB5407 (3).

To test the consequences of artificial induction of the ilv-leu operon on the growth behavior of the ccpA mutant strain, we determined the generation times of the ccpA mutant GP325 in which the ilv-leu operon is under control of the xylose-inducible promoter. The isogenic parent strain, QB5407, served as a control. As described above, this ccpA mutant strain grew, albeit slowly, on CE-Glc minimal medium. The addition of caseine hydrolysate resulted in a drastic decrease of the generation time (55 versus 155 min; see Table 1 and Fig. 1B). The addition of xylose had no effect on the growth of this strain. The addition of methionine resulted in an intermediate generation time (Table 1). Strain GP325 was unable to grow on CE-Glc medium supplemented with only methionine. A combined addition of methionine and caseine hydrolysate allowed rapid growth comparable to that of strain QB5407 in CE-Glc in the presence of caseine hydrolysate. Interestingly, a similar generation time was observed for growth of GP325 in CE-Glc medium supplemented with methionine and xylose to induce the ilv-leu operon. Finally, the effect of branched-chain amino acids and methionine on the growth of the ccpA mutant is cumulative, as derived from the observation that artificial induction of the ilv-leu operon in the absence of methionine was not sufficient to allow the fastest growth of GP325 (Table 1). Taken together, our data demonstrate that the reduced expression of the ilv-leu operon is a bottleneck for the growth of the ccpA mutant.

TABLE 1.

Growth rates of B. subtilis ccpA mutant strains expressing the ilv-leu operon from its own or a xylose-inducible promotera

| Strain (genotype) | Amino acid addition(s) | Generation time (min)b |

|---|---|---|

| QB5407 (ccpA) | None | 155 ± 7 |

| CAA | 55 ± 1 | |

| Xylose | 156 ± 12 | |

| Met + xylose | 109 ± 1 | |

| GP325 (ccpA PxylA::ilv-leu) | Met | NGc |

| Met + CAA | 55 ± 5 | |

| Met + xylose | 47 ± 1 | |

| Xylose | 68 ± 0 |

Cells were grown at 37°C under vigorous agitation in CE-Glc minimal medium supplemented with caseine hydrolysate (CAA) (0.1% wt/vol), methionine (met) (0.002% wt/vol), or xylose (1.5% wt/vol) as indicated. The growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm.

The generation times were determined from the growth of at least three independent cultures under each condition.

NG, no growth.

With the work presented in this study, the main factors that cause the growth defect of the B. subtilis ccpA mutant strains are elucidated. The addition of glutamate, methionine, and branched-chain amino acids to minimal media can completely overcome this defect. These findings demonstrate that CcpA is involved not only in the control of carbon catabolism but also in the regulation of amino acid biosyntheses.

The regulation of the B. subtilis ilv-leu operon had been studied in previous works to some details. In the presence of leucine, transcription of the operon is terminated at a terminator upstream of the first structural gene, ilvB. In the absence of leucine, antitermination occurs by a mechanism involving an RNA structure, the T box, and uncharged tRNALeu (8, 10). In the course of our studies we observed an about 10-fold repression of expression of the ilv-leu operon in the presence of caseine hydrolysate. This fits well with the previously demonstrated regulation of the operon by termination and antitermination in response to the presence of leucine. However, the results presented here show that amino acid regulation is not the only mechanism by which expression of the ilv-leu operon is controlled. As observed for the gltAB operon encoding glutamate synthase (3), maximal expression of the ilv-leu operon occurs only in the presence of glucose. This coupling of expression of amino acid biosynthetic operons to the presence of glucose may help to coordinate carbon and nitrogen metabolism. In the absence of glucose as a source of carbon backbones and energy for biosynthetic pathways, there is no need for the cell to produce large amounts of amino acids.

While the regulation of individual metabolic pathways has been intensively studied with different bacteria, not much is known about the coordination of different metabolic pathways. For E. coli, specific components of the phosphotransferase system and the Crp-cAMP complex provide links between carbon and nitrogen metabolism (19, 22). Moreover, sulfur availability was proposed to control cAMP synthesis and thereby expression of genes involved in carbon catabolism for E. coli (18). The work presented here indicates that there is a tight coupling of carbon and nitrogen metabolism for B. subtilis as well and that CcpA is involved in integrating the different metabolic branches to achieve well-balanced growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wolfgang Hillen, who provided a stimulating scientific environment. Ulrike Mäder is acknowledged for helpful discussions and for allowing us to cite results prior to publication. We are grateful to Thomas Wiegert and Wolfgang Schumann for the gift of plasmid pX2.

This work was supported by the DFG priority program “Regulatorische Netzwerke in Bakterien” and by grants from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to J.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohannon, D. E., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1989. Positive regulation of glutamate biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 171:4718-4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutscher, J., A. Galinier, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2002. Carbohydrate uptake and metabolism, p. 129-150. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Faires, N., S. Tobisch, S. Bachem, I. Martin-Verstraete, M. Hecker, and J. Stülke. 1999. The catabolite control protein CcpA controls ammonium assimilation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:141-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillinger, S., S. Boschi-Muller, S. Azza, E. Dervyn, G. Branlant, and S. Aymerich. 2000. Two glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases with opposite physiological roles in a nonphotosynthetic bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14031-14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher, S. H., and M. Débarbouillé. 2002. Nitrogen source utilization and its regulation, p. 181-191. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 6.Galinier, A., J. Haiech, M.-C. Kilhoffer, M. Jaquinod, J. Stülke, J. Deutscher, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 1997. The Bacillus subtilis crh gene encodes a HPr-like protein involved in carbon catabolite repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8439-8444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galinier, A., J. Deutscher, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 1999. Phosphorylation of either Crh or HPr mediates binding of CcpA to the Bacillus subtilis xyn cre and catabolite repression of the xyn operon. J. Mol. Biol. 286:307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grandoni, J. A., S. A. Zahler, and J. M. Calvo. 1992. Transcriptional regulation of the ilv-leu operon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:3212-3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henkin, T. M., F. J. Grundy, W. L. Nicholson, and G. H. Chambliss. 1991. Catabolite repression of alpha-amylase gene expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacI and galR repressors. Mol. Microbiol. 5:575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henkin, T. M. 1994. tRNA-directed transcription antitermination. Mol. Microbiol. 13:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krüger, S., J. Stülke, and M. Hecker. 1993. Catabolite repression of β-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2047-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindner, C., J. Stülke, and M. Hecker. 1994. Regulation of xylanolytic enzymes in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 140:753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig, H., and J. Stülke. 2001. The Bacillus subtilis catabolite control protein CcpA exerts all its regulatory functions by DNA-binding. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludwig, H., G. Homuth, M. Schmalisch, F. M. Dyka, M. Hecker, and J. Stülke. 2001. Transcription of glycolytic genes and operons in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for the presence of multiple levels of control of the gapA operon. Mol. Microbiol. 41:409-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludwig, H., N. Rebhan, H.-M. Blencke, M. Merzbacher, and J. Stülke. 2002. Control of the glycolytic gapA operon by the catabolite control protein A in Bacillus subtilis: a novel mechanism of CcpA-mediated regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 45:543-553. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Miwa, Y., M. Saikawa, and Y. Fujita. 1994. Possible function and some properties of the CcpA protein of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 140:2567-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogk, A., G. Homuth, C. Scholz, L. Kim, F. X. Schmid, and W. Schumann. 1997. The GroE chaperonin machine is a major modulator of the CIRCE heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 16:4579-4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan, J. A., B. L. Schneider, I. T. Paulsen, M. Yamada, N. M. Kredich, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2002. Regulation of carbon utilization by sulfur availability in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 148:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reizer, J., A. Reizer, M. H. Saier, Jr., and G. R. Jacobson. 1992. A proposed link between nitrogen and carbon metabolism involving protein phosphorylation in bacteria. Protein Sci. 1:722-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stülke, J., and W. Hillen. 2000. Regulation of carbon catabolism in Bacillus species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:849-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stülke, J., I. Martin-Verstraete, M. Zagorec, M. Rose, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1997. Induction of the Bacillus subtilis ptsGHI operon by glucose is controlled by a novel antiterminator, GlcT. Mol. Microbiol. 25:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian, Z.-X., Q.-S. Li, M. Buck, A. Kolb, and Y.-P. Wang. 2001. The CRP-cAMP complex and downregulation of the glnAp2 promoter provides a novel regulatory linkage between carbon metabolism and nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:911-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tobisch, S., D. Zühlke, J. Bernhardt, J. Stülke, and M. Hecker. 1999. Role of CcpA in regulation of the central pathways of carbon catabolism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6996-7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wray, L. W., Jr., F. K. Pettengill, and S. H. Fisher. 1994. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis hut operon requires a cis-acting site located downstream of the transcription initiation site. J. Bacteriol. 176:1894-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]