Abstract

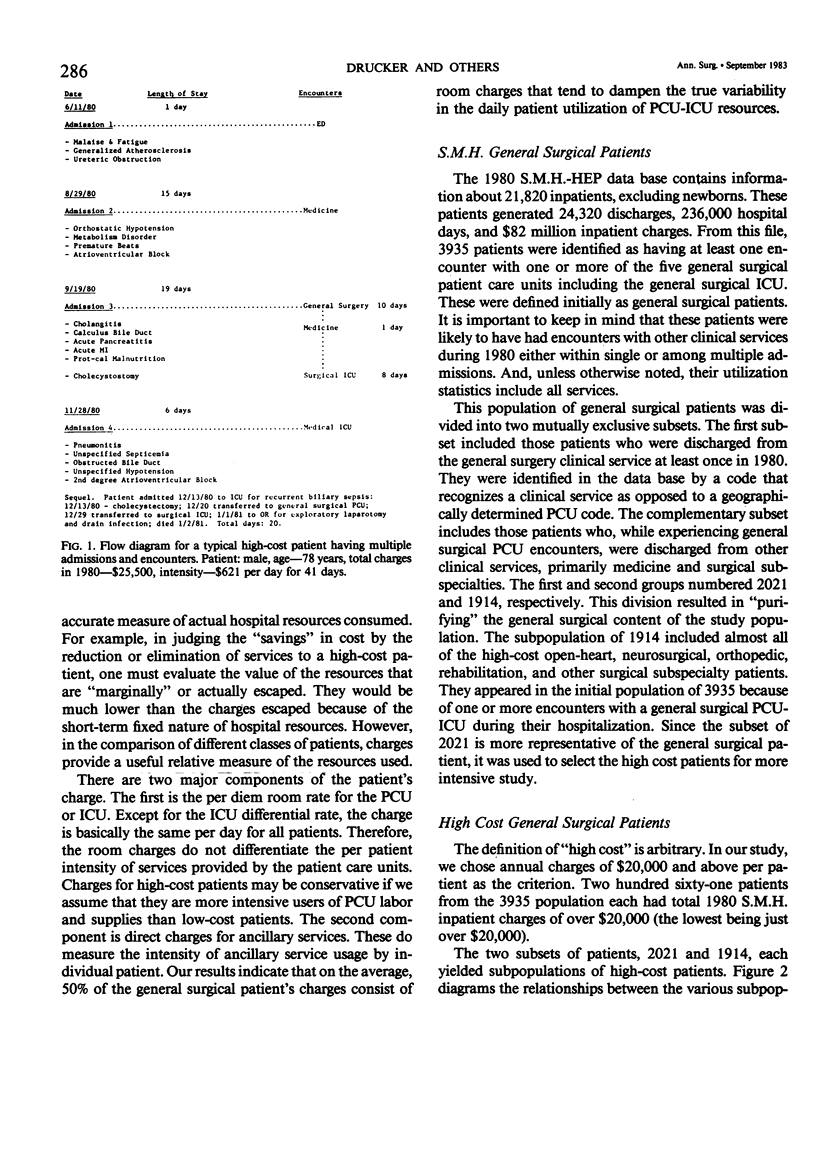

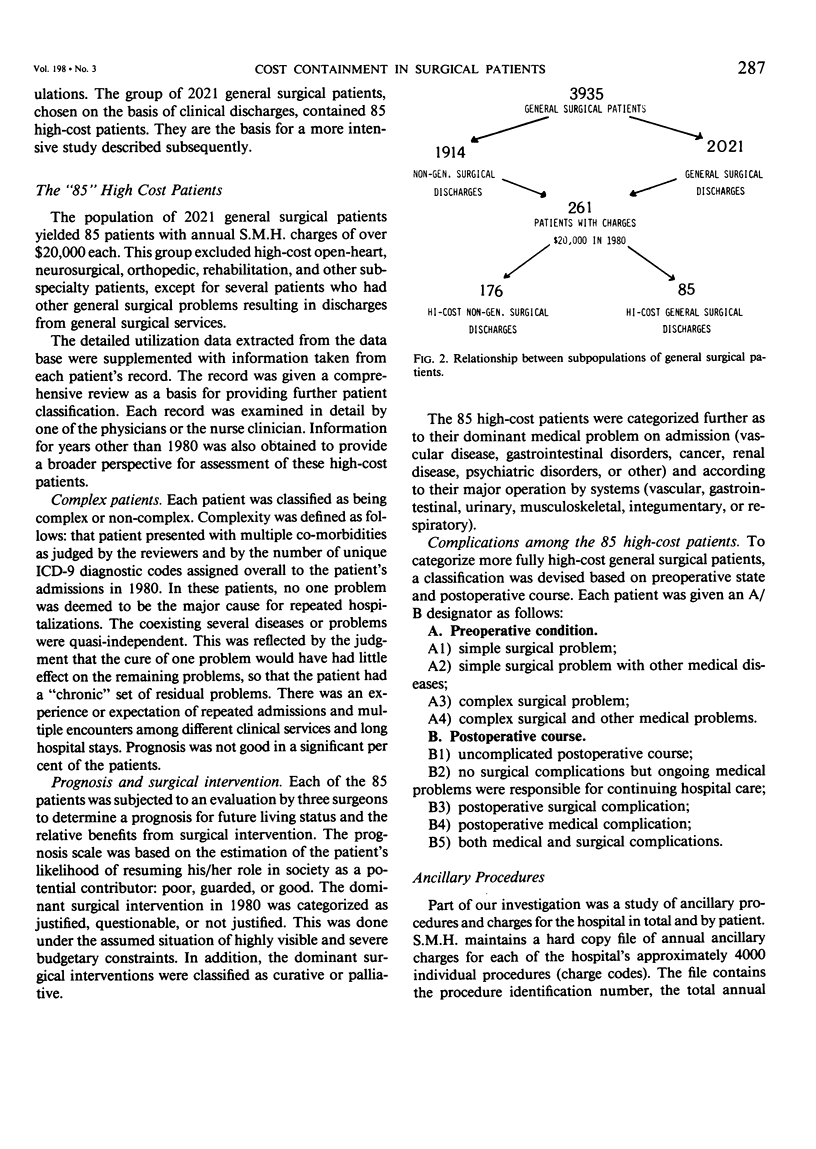

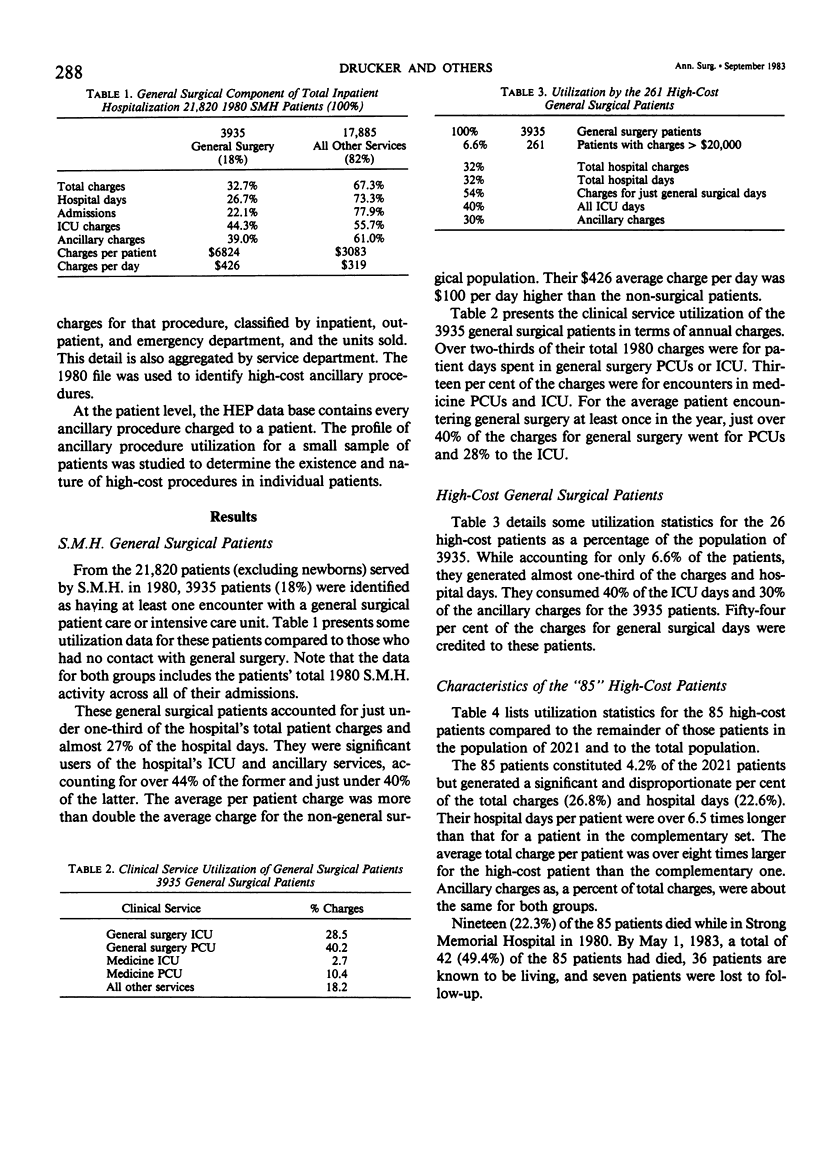

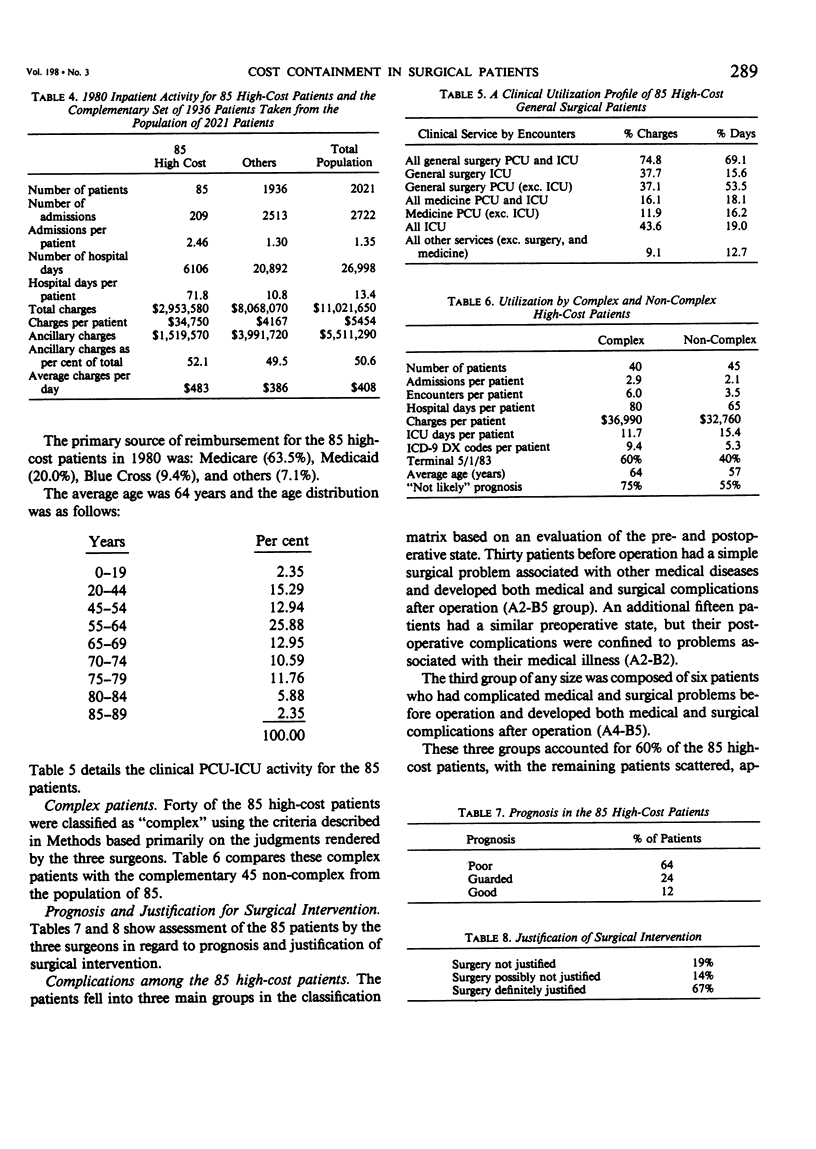

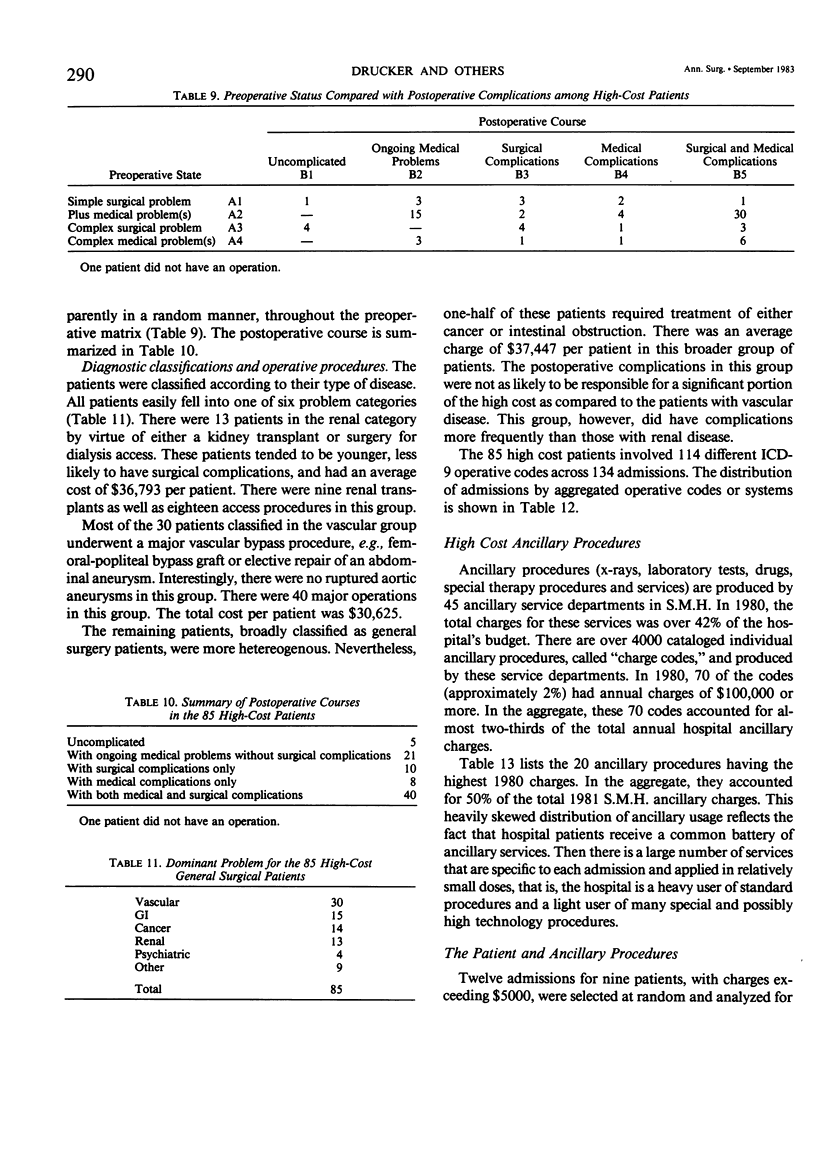

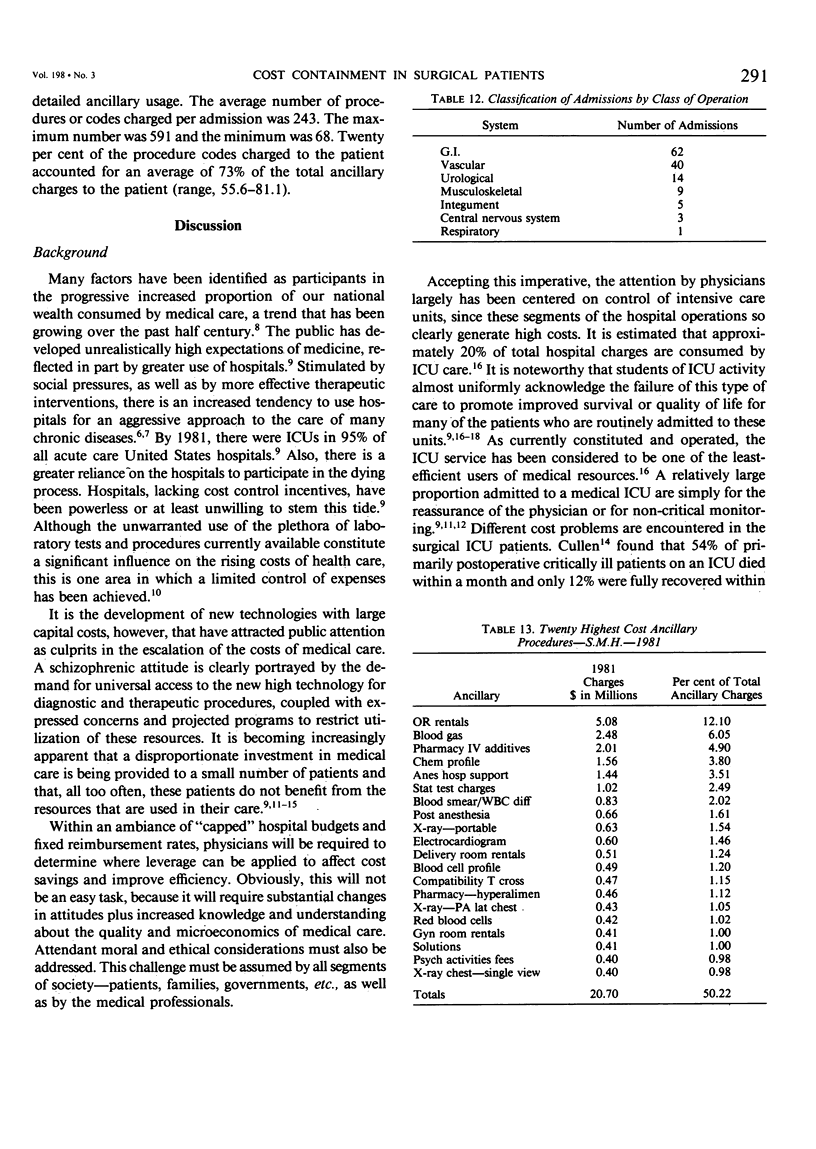

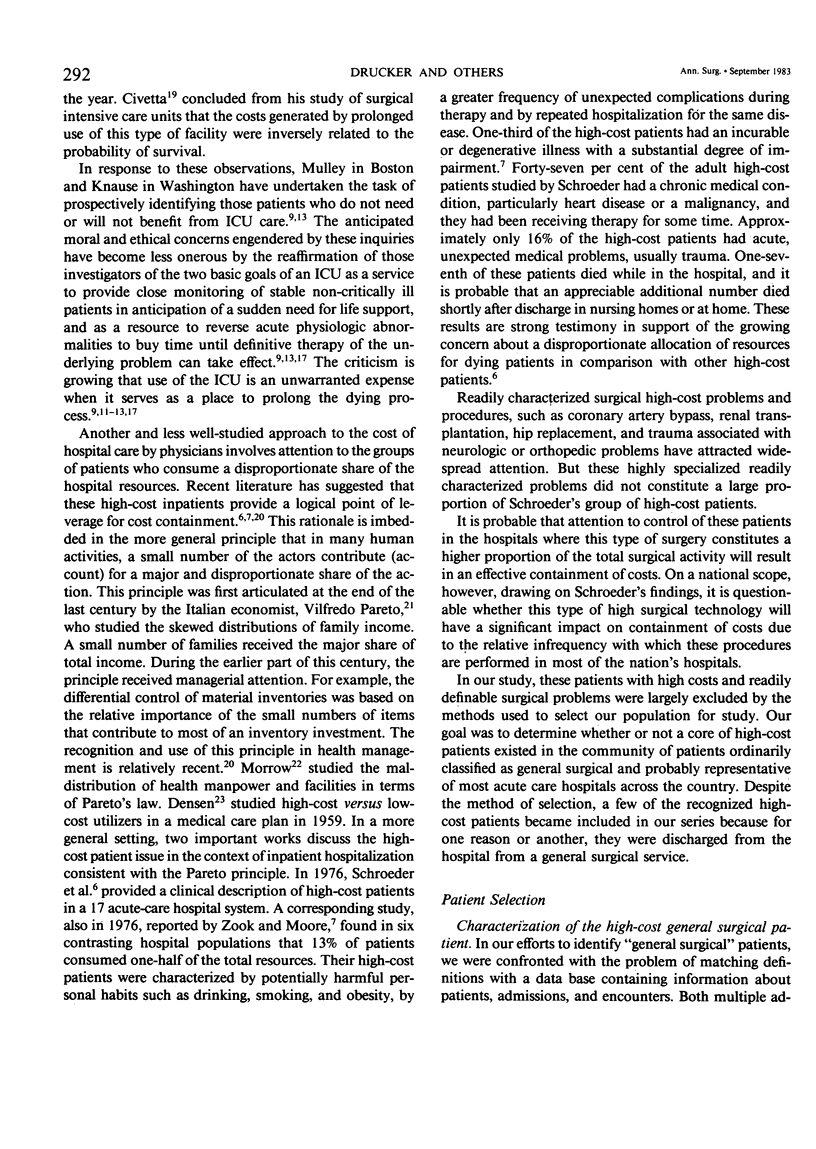

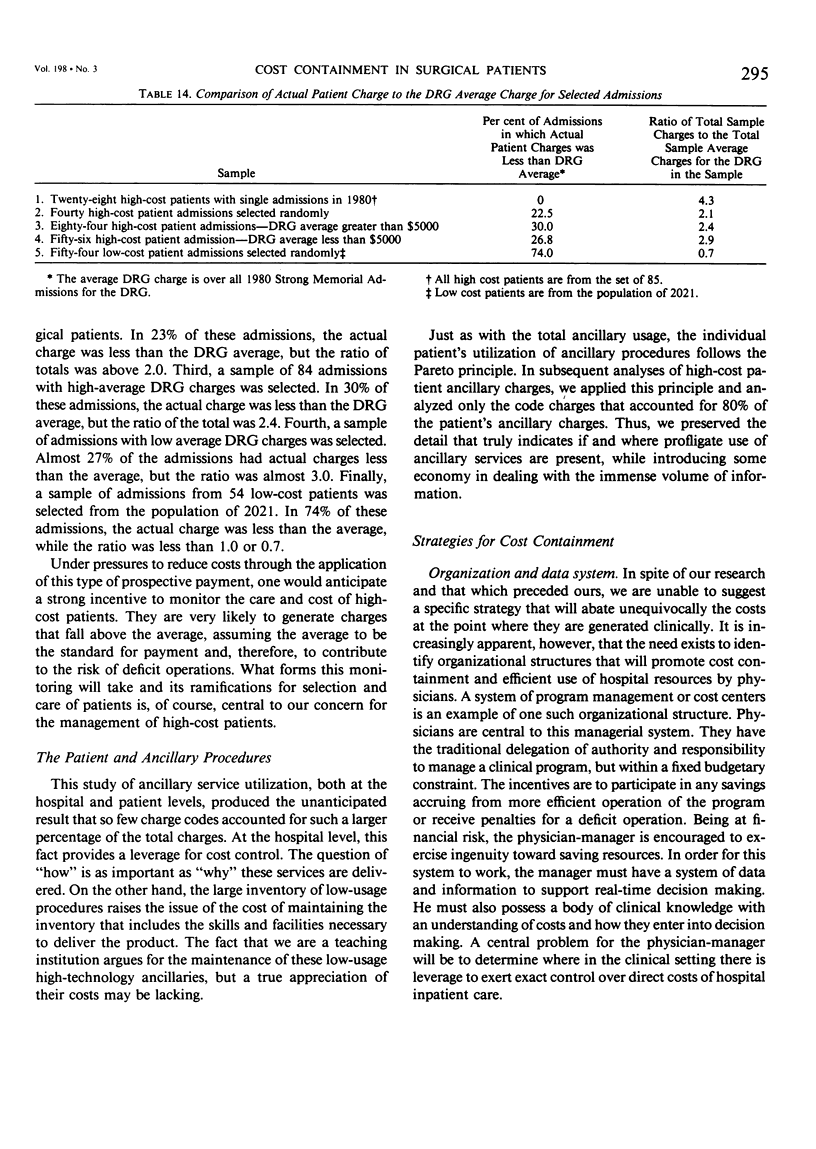

The University of Rochester, Department of Surgery, in response to an experimental community-wide limit on hospital budgets, studied high-cost general surgical patients as a potential source of leverage for containment of hospital costs. It was found that a small number of patients impact significantly on hospital costs. In 1980, 3935 patients at Strong Memorial Hospital (SMH) had at least one contact with a general surgical patient care or intensive care unit; 261 patients (6.6%) had total 1980 charges of more than $20,000 each. They contributed 32% of the total of both general surgical charges and patient days. A subset of 2021 patients was selected to represent more precisely the general surgical patient. The 85 high-cost patients (4.2%) of this subset were chosen for intensive study. These patients generated a significant and disproportionate per cent of total (2021) general surgical charges (26.8%) and hospital days (27.6%). Average total charges were more than 8 times those of the complementary general surgical subset (1936). Nineteen of the 85 patients (22.3%) died in the hospital and 42 patients (49.4%) were dead within 2 1/2 years. Forty patients (of the 85) were then further identified as "complex", based on multiple, usually unrelated, illnesses and multiple annual admissions. Tending to be elderly with poor prognoses, 60% of them had died by April 1983. The major criterion of complexity was the lack of a well-focused medical problem; the cure for one problem simply relinquished primacy to another. A parallel study of hospital ancillary procedures disclosed a similar high-cost pattern. Of approximately 4000 ancillary procedures, 100 (2.5%) had annual charges of $100,000 or over, accounting for two-thirds of total 1980 ancillary charges. Roughly 20% of a single patient's ordered procedures accounted for 80% of the patient's ancillary charges, thus allowing concentrated study of a relatively small number of charges. Means for cost containment may be applied logically to the high-cost patient and particularly toward the complex patient. The complex patient is especially suited for consideration, since it is postulated that these patients are endemic to all general hospitals and to all clinical services. Strategies to be developed should include: 1) a managerial system in which physicians have an incentive to contain costs, 2) an online data system, 3) an accurate, efficient way to identify prospective high-cost and complex patients and, 4) awareness by physicians, patients, and society that less expensive modes of diagnosis and therapy are an appropriate response to rationed health resources.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Campion E. W., Mulley A. G., Goldstein R. L., Barnett G. O., Thibault G. E. Medical intensive care for the elderly. A study of current use, costs, and outcomes. JAMA. 1981 Nov 6;246(18):2052–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers T. C., Stern A. R. The staggering cost of prolonging life. Bus Week. 1981 Feb 23;(2676):19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin M. R. Costs and outcomes of medical intensive care. Med Care. 1982 Feb;20(2):165–179. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civetta J. M. The inverse relationship between cost and survival. J Surg Res. 1973 Mar;14(3):265–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(73)90144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch N. P., Tilney N. L., Moore F. D. The cost of misadventures in colonic surgery. A model for the analysis of adverse outcomes in standard procedures. Am J Surg. 1978 May;135(5):641–646. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch N. P., Tilney N. L., Rayner A. A., Moore F. D. The high cost of low-frequency events: the anatomy and economics of surgical mishaps. N Engl J Med. 1981 Mar 12;304(11):634–637. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198103123041103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen D. J., Ferrara L. C., Briggs B. A., Walker P. F., Gilbert J. Survival, hospitalization charges and follow-up results in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 29;294(18):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604292941805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENSEN P. M., SHAPIRO S., EINHORN M. Concerning high and low utilizers of service in a medical care plan, and the persistence of utilization levels over a three year period. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1959 Jul;37(3):217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese J. A., Rob C. G. Autogenous venous grafts ten years later. Surgery. 1977 Dec;82(6):755–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detsky A. S., Stricker S. C., Mulley A. G., Thibault G. E. Prognosis, survival, and the expenditure of hospital resources for patients in an intensive-care unit. N Engl J Med. 1981 Sep 17;305(12):667–672. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198109173051204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs V. R. A more effective, efficient and equitable system. West J Med. 1976 Jul;125(1):3–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner P. F. Use of laboratory tests in a teaching hospital: long-term trends: reductions in use and relative cost. Ann Intern Med. 1979 Feb;90(2):243–248. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-2-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook E. W., 3rd, Horton C. A., Schaberg D. R. Failure of intensive care unit support to influence mortality from pneumococcal bacteremia. JAMA. 1983 Feb 25;249(8):1055–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus W. A. Changing the cause of death. JAMA. 1983 Feb 25;249(8):1059–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney J. V., Jr Presidential address: the limits of medicine. Ann Surg. 1981 Sep;194(3):247–255. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198109000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow J. S. Toward a more normative assessment of maldistribution: the Gini Index. Inquiry. 1977 Sep;14(3):278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S. A., Showstack J. A., Roberts H. E. Frequency and clinical description of high-cost patients in 17 acute-care hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 7;300(23):1306–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906073002304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S. A., Showstack J. A., Schwartz J. Survival of adult high-cost patients. Report of a follow-up study from nine acute-care hospitals. JAMA. 1981 Apr 10;245(14):1446–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen A. A., Saward E. W., Stewart D. W. Hospital cost containment in Rochester: from Maxicap to the hospital experimental payments program. Inquiry. 1982 Winter;19(4):327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G. E., Mulley A. G., Barnett G. O., Goldstein R. L., Reder V. A., Sherman E. L., Skinner E. R. Medical intensive care: indications, interventions, and outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1980 Apr 24;302(17):938–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004243021703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook C. J., Moore F. D. High-cost users of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1980 May 1;302(18):996–1002. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]