Abstract

The PhoP-PhoQ two-component system plays a role in Mg2+ homeostasis and/or the virulence properties of a number of bacterial species. A Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ sensor kinase mutant, in which the threonine at residue 48 in the periplasmic sensor domain is changed to an isoleucine, was shown previously to result in elevated expression of PhoP-activated genes and to affect mouse virulence, epithelial cell invasion, and sensitivity to macrophage killing. We characterized a complete set of proteins having amino acid substitutions at position 48 in the closely related Escherichia coli PhoQ protein. Numerous mutant proteins having amino acid substitutions with side chains of various sizes and characters displayed signaling phenotypes similar to that of the wild-type protein, indicating that interactions mediated by the wild-type threonine side chain are not required for normal protein function. Changes to amino acids with aromatic side chains had little impact on signaling in response to extracellular Mg2+ but resulted in reduced sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+, suggesting that the mechanisms of signal transduction in response to these two divalent cations are different. Surprisingly, the Ile48 protein displayed a defective phenotype rather than the hyperactive phenotype seen with the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium protein. We also describe a mutant PhoQ protein lacking the extracellular sensor domain with a defect in the ability to activate PhoP. The defect does not appear to be due to reduced autokinase activity but rather appears to be due to an effect on the stability of the aspartyl-phosphate bond of phospho-PhoP.

The PhoP-PhoQ signaling system is a member of a large family of two-component regulatory systems that mediate adaptive responses to diverse stimuli (for reviews, see references 15 and 33 to 35). PhoQ is a transmembrane histidine kinase that responds to low extracellular concentrations of divalent cations by activating PhoP-mediated transcriptional regulation of a set of genes. Like activation of other members of the two-component family, activation of PhoP requires autophosphorylation of PhoQ and subsequent phosphoryl transfer to PhoP (11). This system has been studied extensively in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which more than 40 different genes are directly or indirectly regulated (24); these genes include several genes involved in resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (12, 13), survival in macrophages (24, 25), and epithelial cell invasion (1). In addition to a role in virulence, the PhoP-PhoQ system controls the expression of at least two magnesium transporters that are required for growth at low Mg2+ concentrations (8). PhoP-PhoQ is also present in numerous other gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli, in which a role in survival in limiting Mg2+ has been proposed (8). The PhoP and PhoQ proteins of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli, which are 93 and 86% identical, respectively (18), are likely to be mechanistically similar.

Mg2+ and Ca2+ are thought to act as physiologically relevant signaling ligands by binding directly to the extracellular PhoQ sensor domain and eliciting a conformational change that alters the intracellular enzymatic activities involved in activation of PhoP (8). In support of this idea, divalent cations stabilize an E. coli sensor domain fragment in a fashion expected for a direct binding model, and mutagenesis of an acidic cluster of amino acids has identified a region of the sensor domain that is required for strong divalent cation binding in vitro and affects the normal response to Mg2+ limitation in vivo (39).Two observations suggest that divalent cation binding induces a conformational change in PhoQ in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mg2+ alters the trypsin digestion pattern of PhoQ (8), and both Mg2+ and Ca2+ alter the fluorescence properties of a sensor domain fragment in vitro (9). Identification of divalent cations as signaling ligands makes PhoQ an attractive candidate with which to study the mechanism of signal transduction; however, the nature of the ligand-induced conformational change remains unclear.

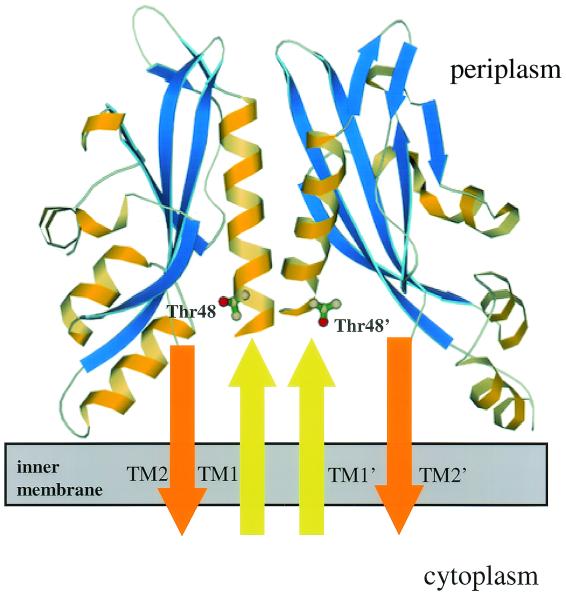

A threonine-to-isoleucine substitution at residue 48 (T48I) of the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ protein results in elevated expression of PhoP-activated genes (8, 19, 20, 24) and reduced expression of PhoP-repressed genes (24). Gunn et al. have shown that this phenotype is due to increased net phosphotransfer from PhoQ to PhoP (11). Presumably, the mutation affects the autokinase, phosphate transfer, and/or (phospho-PhoP-specific) phosphatase activities of PhoQ (11). These authors suggested that the T48I mutation produces a conformational change or stabilizes an oligomeric state that favors net phosphotransfer to PhoP (11). Thr48 resides in the extracellular sensor domain near the first transmembrane segment, where it could influence signal transduction through the transmembrane regions (Fig. 1). The T48I mutant has proven to be useful in identifying genes regulated by the PhoP-PhoQ system in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and in studying the role of this system in bacterial physiology and virulence (1, 12, 23, 41). We have been studying the mechanism of signal transduction in the closely related E. coli PhoP-PhoQ system, and recently the X-ray crystal structure of the extracellular sensor domain has been solved (C. Bingman, J. Schildbach, M. Reyngold, R. Sauer, W. Hendrickson, and C. D. Waldburger, unpublished data). The E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ proteins both possess a threonine at residue 48 and are identical in all nearby residues in their primary structures (18). In this paper, we describe isolation and phenotypic characterization of mutant E. coli PhoQ proteins with all 19 single-amino-acid substitutions at residue 48. We also describe a mutant PhoQ protein lacking the extracellular sensor domain with a defect in the ability to activate PhoP-mediated regulation.

FIG. 1.

Crystal structure of the E. coli PhoQ sensor domain dimer (Bingman et al., unpublished). The side chains of Thr48 and Thr48′, which are four amino acids from the end of transmembrane region 1 in each monomer (TM1 and TM1′), are represented by balls and sticks. The dimer interface formed by sensor domain α-helices is shown as an extension of transmembrane region 1 helices (arrows pointing up). Transmembrane region 2 (TM2) and the contiguous sensor domain residues that are disordered in the crystal structure are represented by arrows pointing down.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

pLPQ2, pNL3, and pPΔQts have been described elsewhere (39). Briefly, pNL3 is a pBR322-derived reporter plasmid in which the PhoP-activated phoN promoter region of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is fused to the lacZ structural gene. pLPQ2 is a pSC101-derived plasmid in which the phoP-phoQ operon of E. coli is driven by the lacUV5 promoter. pPQΔts is a pSC101-derived plasmid with a temperature-sensitive replicon containing the phoP-phoQ operon of E. coli in which codons 25 to 396 of phoQ are deleted. pNL2 (21) is a low-copy-number reporter plasmid in which the phoN-lacZ fusion has been cloned into pGB2 (5). pLPQ3 was constructed by inserting the 2.5-kb EcoRI-SalI PlacUV5-phoP-phoQ fragment from pLPQ2 (39) into the EcoRI-SalI backbone of pBR322. pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI) is a derivative of pLPQ3 in which HindIII and NcoI restriction sites have been introduced in phoQ at codons 42 to 44 and 189 to 191, respectively, by the Sculptor mutagenesis system (Amersham Life Science). The mutations that create the HindIII site are silent, and the mutations that create the NcoI site result in a serine in place of the wild-type tyrosine at residue 189. pLPQ3λ is a derivative of pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI) in which a ∼1.25-kb HindIII-NcoI stuffer fragment corresponding to bp 23901 to 25157 of λ has been cloned into the HindIII-NcoI backbone of pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI). pLPQ2λ is a derivative of pLPQ2 with the identical λ stuffer fragment in phoQ. pLPQ3[N] is the same as pLPQ3 except that the NdeI site that is normally present in pBR322 has been destroyed by cutting with NdeI, filling in the 5′ overhangs by using the Klenow fragment, and religating. pLQ3[N] is the same as pLPQ3[N] except that the phoP gene has been removed and phoQ is fused to the lacUV5 promoter region at a synthetic NdeI site that overlaps the initiating ATG codon of phoQ. pMS802 is a pSC101-based plasmid containing lacIq (38). pLPQ3St and pLPQ3St-T48I are pBR322 derivatives in which S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoP phoQ expression is driven by the lacUV5 promoter. A DNA fragment encoding the phoP and phoQ genes was generated by PCR by using chromosomal DNA from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (wild-type phoQ) and TA2367 (phoQ-TI48) (20) and was fused to the lacUV5 promoter in place of the E. coli phoPQ operon in pLPQ3[N] to create pLPQ3St and pLPQ3St-T48I, respectively. pAED4/PhoP-His6 is a pUC19-derived plasmid used to express a PhoP variant with six histidines added to the C terminus. A DNA fragment encoding PhoP with the six-His addition was generated by PCR by using primers 5′-CGCGATCCATATGACCATGATTACGGATTCACTGGCCGTCG-3′ and 5′-CGCGAATTCTCATCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGCGCAATTCGAACAGATAGCCCTG-3′ and pLPQ3[N] as the template. The PCR product was cut with NdeI and EcoRI (generated by the primers) and cloned into the NdeI-EcoRI backbone of pAED4 (6). The resulting plasmid has the phoP-His6 gene fused to the T7 φ10 promoter and ribosome binding site. Details concerning plasmid construction are available upon request.

Plasmid-borne mutations.

In general, mutations at codon 48 of phoQ were made by generating a PCR fragment corresponding to the region of phoQ between the HindIII and NcoI sites of pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI) by using primer A (5′-GATCGGTTATAGCGTAAGCTTCGATAAAACTXXXTTTCGGCTG-3′), primer B (5′-CCAGCTCCAGAACATGTAGGAACTTTTTAGCTCCACCTT-3′), and pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI) as the template. The Xs in primer A correspond to codon 48 in phoQ and contained bases described below. The PCR fragment was cut with HindIII and AflIII (generated by primers A and B, respectively) and was cloned into the HindIII-NcoI backbone of pLPQ3λ or pLPQ2λ. Note that this cloning procedure recreated the wild-type tyrosine codon at position 189 of phoQ. phoQ-T48I was generated by using primer A with ATC at the position corresponding to codon 48 in phoQ. Ala, Phe, Gly, Leu, Arg, Ser, Trp, Val, and Tyr substitutions were generated by using NNG/C at the position corresponding to codon 48, where N represents a 25% probability of any of the four bases and G/C represents a 50% probability of either G or C. Glu, Gln, Asn, and Lys substitutions were generated by using C/A/GAN at the position corresponding to codon 48, where C/A/G represents an equal probability of C, A, or G. Cys, Asp, His, Met, and Pro were generated by using TGC, GAC, CAC, ATG, and CCC, respectively, at the position corresponding to codon 48. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing by using double-stranded plasmid DNA as the template. pLPQΔSD2 was constructed by ligating a double-stranded cassette (top strand, 5′-AGCTTCGATAAAACTACGTTTAGGCCTGTGGAGCTCAAAAGTTCCTC-3′; bottom strand, 5′-CATGGAGGAACTTTTGAGCTCCACAGGCCTAAACGTAGTTTTATCGA-3′) into the HindIII-NcoI backbone of pLPQ3 (HindIII-NcoI). This resulted in an in-frame deletion in phoQ in which codon 50 was fused to codon 182. The sequence of this region was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the ∼2.1-kb EcoRI-SalI PlacUV5-phoP-phoQ-ΔSD fragment was cloned into the EcoRI-SalI backbone of pGB2 (5) to create pLPQΔSD2. pLQΔSD3[N] is a derivative of pLQ3[N] that contains the sensor domain deletion mutation (Δ51-181).

Construction of CSH26 (phoQ-T48I).

The T48I mutation was put into the chromosomal phoQ gene of E. coli CSH26 (22) by the gene replacement method of Hamilton et al. (14). These experiments required a derivative of pPΔQts in which the deleted portion of phoQ (including codon 48) was replaced with an intact phoQ gene with the T48I mutation. This plasmid (pPQT48I-ts) was transformed into CSH26ΔQ (39), and bacteria were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plates supplemented with 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml at 44°C to select for integration of the temperature-sensitive plasmid into the chromosome. Cmr colonies were grown overnight in LB medium at 30°C to allow resolution of the integrated plasmid, and the culture was plated on LB medium-chloramphenicol plates at 30°C. Individual colonies were isolated, and plasmid DNA was extracted and examined by restriction analysis. Colonies containing plasmids with the ΔQ mutation were assumed to have undergone a gene replacement event and were grown on LB medium plates at 44°C to promote loss of the plasmid. Note that the T48I mutation maps to part of phoQ that is missing in the ΔQ mutant, so replacement of the deletion results in chromosomal placement of the T48I mutation. Candidate colonies were screened for Cms, and replacement of the ΔQ allele with phoQ-T48I was confirmed by PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA.

Western blotting and preparation of cell membranes.

Membranes from E. coli CSH26ΔQ cells containing pMS802 and pLPQ2 derivatives with substitutions at residue 48 of phoQ were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting to determine if the mutations affected steady-state protein levels and/or membrane insertion. Briefly, cells containing pLPQ2 derivatives with the codon 48 mutations were grown to the mid-log phase at 37°C under activating conditions (N media in the absence of divalent cations). Cells were harvested and pelleted, and membranes were isolated as follows (28). Spheroplasts were generated by suspending cells in a solution containing 0.2 M Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 0.5 M sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 50 μg of lysozyme per ml and incubating the preparation on ice for 10 min. MgSO4 (final concentration, 20 mM) was then added, and chromosomal DNA was digested by incubating the preparation on ice for 10 min with DNase I (final concentration, 10 μg/ml). The spheroplasts were then lysed by sonication in an ethanol-ice bath (six 30-s pulses with an XL sonicator [Heat Systems Inc.]), and the membrane fractions were recovered by centrifugation as described previously (30). The membranes were then washed once with 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-1 M KCl, once with 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-5 mM EDTA, and twice with 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-15% glycerol. Samples were then normalized for total protein and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) by using a 15% polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. Western analysis was performed as described previously (31) by using an antibody generated against the purified cytoplasmic domain of E. coli PhoQ. Cell membranes enriched for full-length PhoQ or the sensor domain deletion variant were prepared from E. coli CSH26ΔQ cells containing pMS802 and either pLQ3[N] or pLQ-ΔSD3[N]. Cells were grown to the mid-log phase at 37°C in LB medium, protein expression was induced for 2 h with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and membranes were prepared as described above.

Autokinase and phosphotransfer assays.

For the autokinase assays, PhoQ- or PhoQ-ΔSD-enriched cell membranes were diluted in phosphorylation buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 50 mM KCl) to obtain roughly equivalent amounts of PhoQ and PhoQ-ΔSD (0.5 and 2.0 mg of total protein per ml, respectively). The assay was started by addition of a mixture of [γ-32P]ATP (0.1 μCi/μl; NEN) and unlabeled ATP (final concentration, 110 μM). Aliquots (10 μl) were removed at various times, and the reaction was stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For the phosphotransfer assays, PhoQ- and PhoQ-ΔSD-enriched cell membranes (0.5 and 2.0 mg of total protein per ml, respectively) were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and unlabeled ATP (final concentration, 110 μM) for 35 min to allow autophosphorylation to proceed. The zero-time sample was obtained by removing a 10-μl aliquot after the 35-min incubation and stopping the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Purified PhoP-His6 (final concentration, 50 μM) (see below) was then added to the reaction mixture with or without MgCl2 (final concentration, 0.5 mM); 10-μl aliquots were removed at various times, and the reaction was stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For both the autokinase and phosphotransfer assays, proteins were separated on an SDS-10% PAGE gel, and radiolabeled protein bands were visualized by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics). PhoP-His6 was purified from E. coli strain X90(DE3) transformed with pAED4/PhoP-His6 by chromatography on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose (Qiagen, Inc.) as described by the manufacturer for isolation of native proteins.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays (22) were performed with mid-log-phase cultures grown in N media (27) supplemented with various concentrations of divalent cations as indicated below. Unless otherwise noted, the standard deviations were less than 20% of the means. Most assays were performed with cultures grown in glass tubes; the exceptions were the assays whose results are shown in Table 1, which were performed in disposable plastic tubes. Presumably, the lower level of expression observed for the wild type grown in glass tubes was due to residual divalent cations left from the washing process.

TABLE 1.

Effects of PhoQ and a PhoQ sensor deletion mutant on PhoP-mediated transcriptiona

| phoQ | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No MgCl2 | 10 μM MgCl2 | 10 mM MgCl2 | |

| Wild type | 3,576 ± 704 | 391.8 ± 63.8 | 29.3 ± 6.8 |

| Sensor deletion | 475.5 ± 161.8 | 106.6 ± 5.9 | 71.8 ± 11.5 |

| None | 11.0 ± 2.2 | 15.4 ± 3.7 | 23.6 ± 5.6 |

E. coli strain CSH26ΔQ/F′ lacIq kan (39) carrying the pNL3 reporter plasmid and a pGB2 derivative (expressing phoP plus wild-type phoQ or phoQ-ΔSD) or pGB2 (negative control) was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N minimal medium supplemented with 0 or 10 μM or 10 mM MgCl2. The values are means ± standard deviations calculated from three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Full spectrum of amino acid substitutions at residue 48 of E. coli PhoQ.

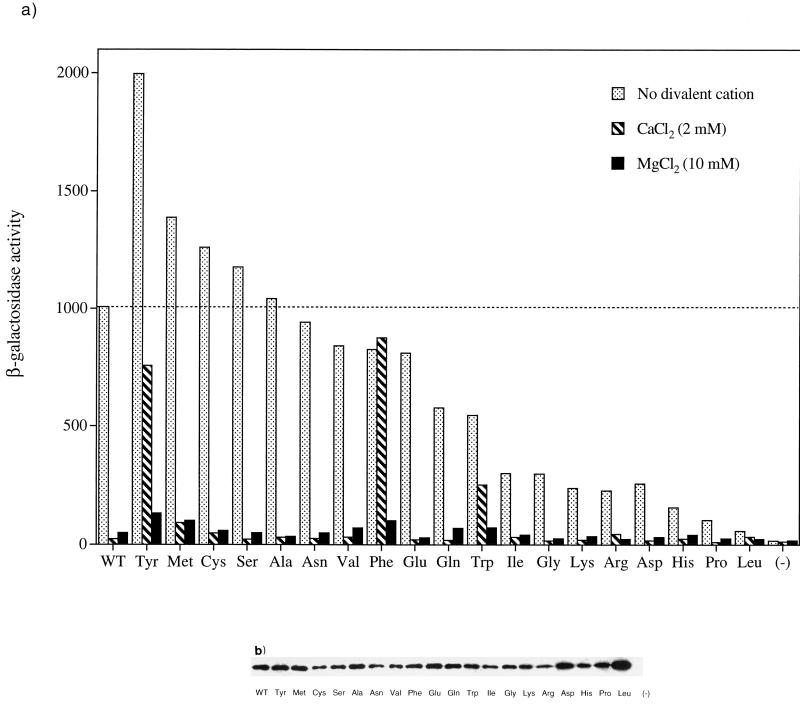

A mutation in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoQ gene which results in a threonine residue at codon 48 being replaced with an isoleucine results in overexpression of several PhoP-activated genes (8, 19, 20, 24). This hyperactive phenotype is most prominent at submaximal repressing concentrations of Mg2+ or Ca2+ and results in roughly two- to eightfold-higher expression of a PhoP-dependent reporter gene (8, 9, 19). We have been studying the mechanism of signal transduction in the closely related E. coli PhoQ protein. Since the PhoQ proteins of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli are 86% identical, including all residues near Thr48 in the primary structure, we reasoned that changes at this position in the E. coli PhoQ protein might result in a similar hyperactive phenotype. To test this idea and to analyze in greater detail how changes at this position alter signaling, we constructed a set of 19 mutants with mutations covering the full spectrum of possible amino acid substitutions at residue 48 in the E. coli PhoQ protein. We then assayed the abilities of these mutants to activate transcription from a PhoP-dependent phoN-lacZ reporter gene (39) in the absence and in the presence of extracellular Mg2+ or Ca2+; the results are shown in Fig. 2a. We placed each of the PhoQ mutants into one of the following three classes: (i) mutants in which the expression levels were similar to the level supported by the wild-type protein, both in the absence and in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Cys, Met, Ser, Ala, Asn, Val, Glu, and Gln) (class I); (ii) mutants with decreased sensitivity to repression by Ca2+ but not by Mg2+ (Tyr, Phe, and Trp) (class II); and (iii) mutants that supported less than 30% of the wild-type levels of reporter expression in the absence of divalent cations, which were classified as defective (Ile, Gly, Arg, Asp, His, Lys, Pro, and Leu) (class III). The number of amino acid substitution-containing proteins with side chains having different sizes and characters that display a phenotype similar to that of the wild type suggests that interactions mediated by the wild-type threonine side chain are not necessary for normal protein function. Somewhat surprisingly, only a mutant with a tyrosine substitution-containing protein displays a hyperactive phenotype in the absence and in the presence of divalent cations similar to that of the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ-T48I mutant, and E. coli PhoQ-T48I actually falls into the category of defective mutants. To determine if the phenotypes of the mutants reflected a change in protein stability or insertion into the membrane, the steady-state level of each mutant was determined by Western blot analysis of membrane preparations by using an antibody directed to the intracellular domain of PhoQ (Fig. 2b). Most of the mutants showed levels of membrane-associated protein similar to the level observed for the wild type, with some slight variances. The defects displayed by the class III mutants were not the result of significant reductions in protein levels. The substituted amino acids that are most detrimental to PhoQ activation in the absence of divalent cations include several large hydrophilic and/or charged residues (His, Arg, Lys, and Asp), helix-destabilizing residues (Gly and Pro), Ile, and Leu. Thr48 resides in an α-helical portion of PhoQ (Fig. 1), which may explain the defective phenotype displayed by the two mutants with helix-breaking substitutions. The severe defect imparted by the T48L mutation is somewhat surprising since mutations to residues with side chains having similar sizes and characters do not result in such a severe phenotype. It may be that the exceptionally high levels of protein seen in the membrane preparations for this mutant led to aggregation that inactivated the protein. The reduced sensitivity to Ca2+ repression exhibited by the Tyr, Phe, and Trp mutants suggests that the aromatic rings in these amino acids may interfere with the normal response to Ca2+. The fact that these mutants are repressed normally by Mg2+ suggests that the mechanisms of repression may differ for the two cations. This could occur if binding occurs at separate sites in the PhoQ sensor domain or if binding at a shared single site results in different structural responses by the protein. García Véscovi et al. have proposed that the sensor domain of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ possesses distinct binding sites for Mg2+ and Ca2+ (9). This hypothesis is based on the finding that together Mg2+ and Ca2+ repress expression of a PhoP-dependent psiD::Mu dJ insertion to a greater extent than either divalent cation individually represses expression and the finding that the PhoQ-T48I mutant is less sensitive to repression by Ca2+ than to repression by Mg2+ (9). We performed similar studies with the E. coli wild-type PhoQ protein but did not observe additive effects of repression by the two divalent cations together (unpublished results). Perhaps our phoN-lacZ reporter system is not sensitive enough to detect small changes in the phosphorylation state of PhoP, or repression of E. coli PhoQ signaling by Mg2+ and Ca2+ may simply differ from repression of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ signaling.

FIG. 2.

(a) In vivo activities of a full set of amino acid variants with substitutions at residue 48 of phoQ. E. coli strain CSH26ΔQ/F′ lacIq kan carrying the pNL3 reporter plasmid and pLPQ2 (expressing phoQ with each of the 20 possible amino acids at residue 48) or pGB2 (negative control) was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium alone or N medium supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2 or 2.0 mM CaCl2. The dashed line indicates the β-galactosidase activity in the presence of the wild-type phoQ gene (Thr48) when cultures were grown in N media lacking divalent cationic salts. The values are means calculated from four to six independent experiments for each variant. The standard deviations were less than 10% of the means in all cases. (b) In vivo steady-state protein levels for PhoQ variants shown in panel a as assayed by Western blot analysis of membrane preparations (see Materials and Methods). WT, wild type.

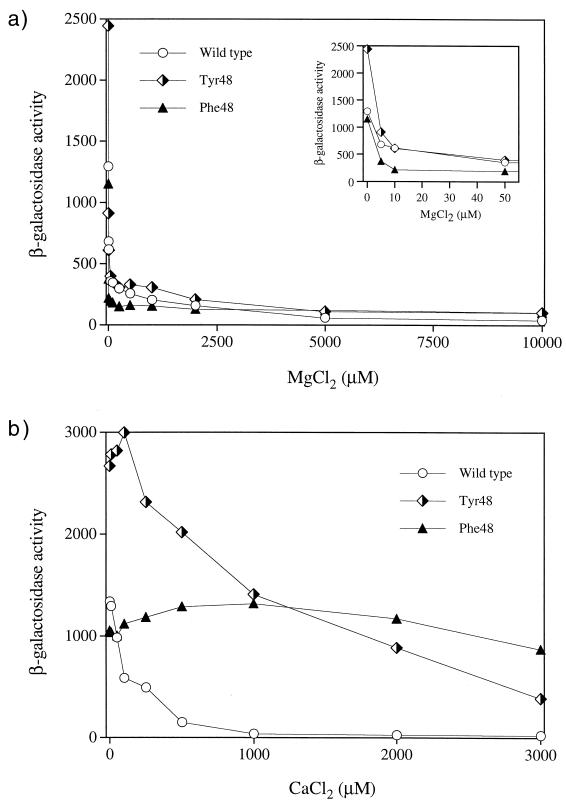

The Tyr48 mutant was roughly twofold more active than the Phe48 mutant in terms of the ability to promote reporter expression when the bacteria were grown in the absence of divalent cations (Fig. 2a). However, the Phe48 mutant was insensitive to repression by 2.0 mM Ca2+, whereas expression in the Tyr48 mutant exhibited about threefold repression. To explore the differences between these two mutants in more detail, we assayed reporter expression in response to various concentrations of either Mg2+ or Ca2+, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. Both the Tyr48 and Phe48 mutants produced response curves similar to that of wild-type PhoQ when Mg2+ was the repressing cation (Fig. 3a). In contrast, Tyr48 showed diminished repression by Ca2+, while the Phe48 mutant was essentially insensitive to extracellular Ca2+ at all levels tested (Fig. 3b). The insensitivity displayed by the Phe48 mutant could have resulted from lower affinity for Ca2+ or a defect in the response to Ca2+ binding. The Phe48 mutant produced a response curve similar to that obtained with extracellular Mg2+ when it was grown in the absence or in the presence of 2.0 mM Ca2+ (data not shown), indicating that Ca2+ does not interfere with Mg2+ binding or repression in this mutant. The differences displayed by the Tyr48 mutant compared to the Phe48 variant (elevated activity in the absence of divalent cations and repression that occurred upon Ca2+ addition) were presumably due to the hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring. Perhaps the hydroxyl group can participate in a hydrogen bond that is more conducive to formation of the active state in the absence of Ca2+ and to formation of the inactive state in the presence of Ca2+. Alternatively, the hydrophilic hydroxyl group may interfere with an interaction mediated by the hydrophobic aromatic ring that desensitizes the protein to Ca2+ repression in the Phe48 mutant. Attempts to elucidate the mechanistic basis for the Ca2+-blind phenotype of the PhoQ-Phe48 mutant by examining the in vitro enzymatic activities of membranes enriched with the mutant protein were unsuccessful. Such studies are complicated by the requirement for Mg2+ as a cofactor in the enzymatic reactions mediated by the cytoplasmic kinase domain in addition to its proposed role in signaling mediated through interactions with the sensor domain.

FIG. 3.

In vivo responses of E. coli PhoQ+, PhoQ-T48Y, and PhoQ-T48F proteins to extracellular Mg2+ (a) and Ca2+ (b). E. coli strain CSH26ΔQ/F′ lacIq kan carrying the pNL3 reporter plasmid and pLPQ2 (expressing wild-type phoQ, phoQ-T48Y, or phoQ-T48F) was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium supplemented with various concentrations of MgCl2 (a) or CaCl2 (b). The inset in panel a shows an expanded view of the results obtained with 0 to 50 μM MgCl2. The values are means calculated from four independent experiments.

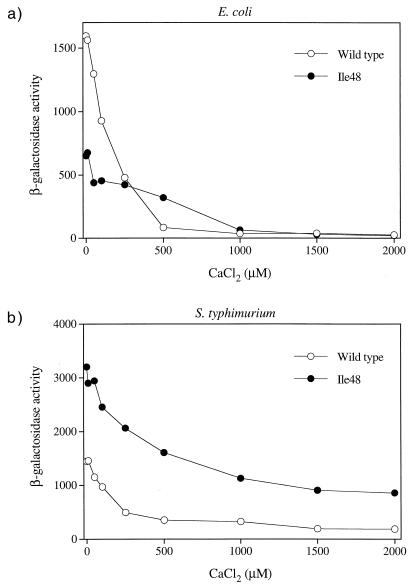

Chromosomal phoQ (T48I) mutant is defective in its response to both Mg2+ and Ca2+ starvation.

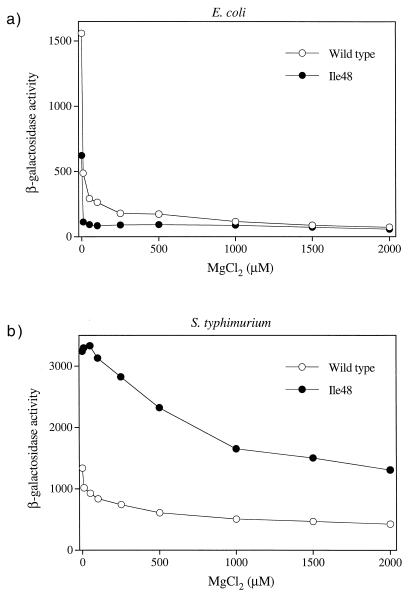

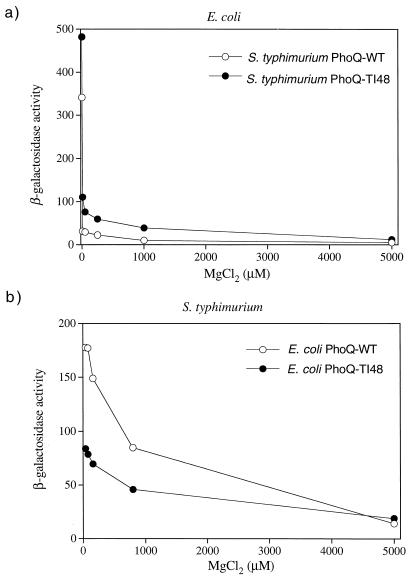

The defective phenotype displayed by PhoQ-Ile48 is surprising in light of the hyperactive phenotype of a similar S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ protein mutant. Although the steady-state protein levels were somewhat less than the wild-type levels, it seemed unlikely that this was the cause of the defect as the levels of several active mutants (e.g., Cys, Asn, and Val) were similar to those of Ile. We hypothesized that the reduced response displayed by the T48I mutant may have been an artifact of the multicopy plasmid vector used in our experiments. To examine this possibility, we constructed an E. coli strain in which the chromosomal phoQ gene contains the T48I mutation (see Materials and Methods) and assayed the abilities of the wild-type and mutant strains to activate transcription of a plasmid-borne phoN-lacZ reporter in response to Mg2+ and Ca2+ limitation. We also assayed activation of the same reporter construct in an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain with a phoQ+ allele and in an isogenic strain containing the phoQ-T48I mutation (20). The T48I mutation in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium produced a hyperactive phenotype, as expected, which resulted in roughly two- to eightfold-higher levels of reporter expression when the bacteria were grown in the presence of 0 to 2.0 mM MgCl2 (Fig. 4b) or 0 to 2.0 mM CaCl2 (Fig. 5b). In contrast, the E. coli phoQ-T48I mutation resulted in a reduced ability to activate the reporter in response to starvation for either Mg2+ (Fig. 4a) or Ca2+ (Fig. 5a). Thus, the Ile48 mutant was defective even when the mutation was expressed from the normal promoter and chromosomal location. The E. coli phoQ-T48I allele did support higher levels of reporter expression at intermediate levels of extracellular Ca2+(Fig. 5a), indicating that the mutant can produce a hyperactive phenotype under some conditions. However, the degree and breadth of the effect were modest compared to the results obtained for the analogous S. enterica serovar Typhimurium allele. The different phenotypes displayed by the E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ-Ile48 variants were not the result of strain differences since a plasmid with the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoQ-T48I mutant gene was hyperactive in E. coli (Fig. 6a) and the E. coli phoQ-T48I mutant gene was defective in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 6b).

FIG. 4.

In vivo responses of chromosomal E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoQ+ and phoQ-T48I alleles to extracellular Mg2+. E. coli strain CSH26 (phoQ+) (22) or CSH26 phoQ-T48I (see Materials and Methods) carrying the pNL3 reporter plasmid (a) or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (phoQ+) or TA2367 (phoQ-T48I) (20) carrying pNL3 (b) was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium supplemented with various concentrations of MgCl2. The values are means calculated from two independent experiments for each variant.

FIG. 5.

In vivo responses of chromosomal E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium yphoQ+ and phoQ-T48I alleles to extracellular Ca2+. E. coli strain CSH26 (phoQ+) or CSH26 phoQ-T48I carrying the pNL3 reporter plasmid (a) or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (phoQ+) or TA2367 (phoQ-T48I) carrying pNL3 (b) was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium supplemented with various concentrations of CaCl2. The values are means calculated from two independent experiments for each variant.

FIG. 6.

(a) In vivo responses of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoQ+ and phoQ-T48I alleles in E. coli. E. coli strain CSH26ΔQ carrying the pNL2 reporter plasmid, pMMB207 (26), and either pLPQ3St or pLPQ3St-T48I was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium supplemented with 25 μM IPTG and various concentrations of MgCl2. (b) In vivo responses of E. coli phoQ+ and phoQ-T48I alleles in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain EG9522 (8) carrying pMMB207 and either pLPQ2 or pLPQ2-T48I was assayed for β-galactosidase activity following growth in N medium supplemented with various concentrations of MgCl2. The values are means calculated from two independent experiments for each variant. WT, wild type.

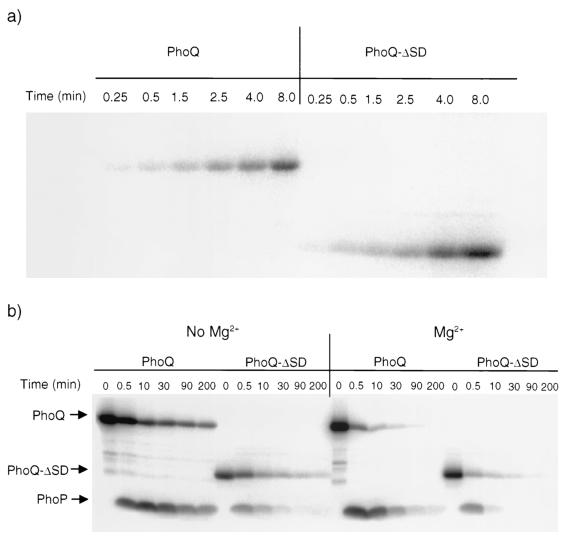

In vivo activity of a sensor deletion mutant.

Deletion of parts or all of the sensor domains of the EnvZ, PhoR, CpxA, and VirA sensor kinases has resulted in constitutively active or inactive signaling phenotypes (4, 36, 37, 42). To test the effects of deleting the PhoQ extracellular domain, we created an in-frame deletion in phoQ that fused codon 50 to codon 182 and assayed the ability of the mutant to activate expression of phoN-lacZ. As shown in Table 1, the PhoQ-ΔSD mutant was defective in the ability to fully activate phoN-lacZ expression in response to Mg2+ limitation and in the ability to fully repress phoN-lacZ expression in response to Mg2+. The defect in activation is not due to mislocalization of the variant protein since Western blot analysis of the cytosolic and membrane fractions indicated that the mutant is associated with the membrane (data not shown). The failure to fully activate could be due to an inability to carry out autophosphorylation, phosphoryl transfer, and/or an enhanced phosphatase activity that destabilizes phospho-PhoP. As shown in Fig. 7a, PhoQ-ΔSD in isolated bacterial membranes underwent autophosphorylation at a rate similar to that observed with the intact protein and was competent to phosphorylate PhoP (Fig. 7b). The stability of phospho-PhoP, however, was significantly decreased in the presence of PhoQ-ΔSD compared to its stability in the presence of PhoQ+ (Fig. 7b), indicating that the sensor domain can influence dephosphorylation of PhoP. Phospho-PhoP was also destabilized when Mg2+ was added to the reaction mixture, which is consistent with a ligand-mediated increase in PhoQ's phosphatase activity; however, this may simply have been due to a catalytic effect on the dephosphorylation reaction since phospho-PhoP was also destabilized by higher Mg2+ concentrations in the presence of PhoQ-ΔSD (Fig. 7b). It is not clear from these studies why the mutant shows slightly higher levels of reporter expression in the presence of Mg2+. Perhaps the in vitro assay is not sensitive enough to detect the small difference between the repressed wild type and the mutant observed in the in vivo reporter assay. The results suggest that the sensor domain of PhoQ responds to its signal(s) by regulating the ability of the kinase domain to destabilize the phosphorylated form of PhoP. The loss of the phospho-PhoP signal was not due to protein degradation but rather was due to destabilization of the aspartyl-phosphate moiety (data not shown). Additional experiments are necessary to elucidate the mechanism of destabilization and to determine if destabilization is modulated by direct interaction of extracellular Mg2+ with the sensor domain.

FIG. 7.

Autokinase (a) and phosphotransfer (b) activities of PhoQ+ and PhoQ-ΔSD. (a) Membranes enriched with PhoQ+ or PhoQ-ΔSD were incubated in 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-50 mM KCl-[γ-32P]ATP at 22°C. Aliquots were removed at different times, and the reaction was stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE buffer. (b) Membranes enriched with PhoQ+ or PhoQ-ΔSD were incubated in 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-50 mM KCl-[γ-32P]ATP at 22°C for 35 min, and purified PhoP was added to a final concentration of 50 μM (0.5 mM MgCl2 was also added where indicated). Aliquots were removed immediately prior to the addition of PhoP (zero time) and at the times after addition indicated, and the reaction was stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE buffer. All samples were subjected to SDS-10% PAGE, and the radiolabeled protein bands were visualized by phosphorimaging.

DISCUSSION

The PhoP-PhoQ regulatory system was identified in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium by isolation of a mutation (pho-24) that resulted in elevated expression of phoN, which encodes a nonspecific acid phosphatase (20). The pho-24 allele was subsequently found to be a mutation in the phoQ gene that results in a threonine-to-isoleucine substitution at residue 48 (8, 11), which is located in the periplasmic sensor domain, four amino acids from the end of transmembrane region 1 (Fig. 1). Although PhoQ-T48I is labeled a constitutive mutant (20, 24), experiments performed by García Véscovi et al. (8, 9) and the experiments described here (Fig. 4b and 5b) revealed that despite its hyperactive phenotype, this mutant is still regulated by extracellular Ca2+ and Mg2+. The pho-24 allele has proven to be useful in identifying phoPQ-dependent genes in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and in studying the role of this system in virulence (1, 12, 23, 24, 41). In the crystal structure of a fragment that corresponds to the extracellular sensor domain of the closely related E. coli PhoQ protein, Thr48 resides in an α-helix that forms the dimer interface between two sensor domain monomers (Fig. 1). The threonine is solvent exposed and does not have any obvious tertiary interactions, so it is difficult to speculate how amino acid changes at this position might result in a hyperactive phenotype. Perhaps the threonine residue forms interactions in the intact protein that are not present in the truncated domain. In order to examine the role that Thr48 plays in signal transduction and to examine how changes at position 48 affect protein function, we assayed the signaling phenotypes of a set of 19 E. coli PhoQ proteins with amino acid substitutions at residue 48. Our studies show that a variety of different residues can substitute for Thr48 with little or no effect on protein function (Fig. 2a). However, some changes in this residue do affect activity in the absence of extracellular divalent cations and also affect sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+, suggesting that residue 48 is important in forming the active state, as well as in Ca2+ detection and/or formation of the Ca2+-mediated repressed state. Our findings that Tyr, Phe, and Trp substitutions dramatically affect sensitivity to repression by Ca2+ but have only minor effects on repression by Mg2+ suggest that the Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations repress PhoQ by different mechanisms. A response to Mg2+ limitation makes sense in light of the fact that expression of the mgtA and mgtCB loci of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, which encode two high-affinity Mg2+ transport systems, and expression of mgtA in E. coli are activated in a PhoP-dependent manner (8; unpublished results). A role for the PhoP-PhoQ system in response to extracellular Ca2+ has not been elucidated. García Véscovi et al. have hypothesized that Mg2+ and Ca2+ repress the PhoP-PhoQ system in mammalian extracellular fluids, where the concentrations of these divalent cations are in the millimolar range (2, 29). After bacterial entry into the cell, Salmonella resides in a phagosome, where lower divalent cation concentrations presumably activate PhoP-PhoQ (8). The finding that the PhoQ protein of a nonpathogenic E. coli strain apparently senses Ca2+ in a manner distinct from the manner used to sense Mg2+ suggests that Ca2+ sensing plays a role in normal bacterial physiology in addition to any role that it may play in bacterial pathogenesis. All bacteria maintain intracellular Ca2+ levels below that of the growth medium by means of membrane transporters (32). None of the roughly 25 loci that are known to be regulated by PhoP-PhoQ in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium appear to play a role in calcium homeostasis. Further experiments are necessary to elucidate the nonpathogenic role of Ca2+ sensing by this system.

The differential responses to extracellular Mg2+ and Ca2+ displayed by the Phe48, Tyr48, and Trp48 mutants are consistent with a model in which Mg2+ and Ca2+ bind distinct sites in the PhoQ sensor domain, as has been hypothesized for the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium protein (9). It has previously been shown that an acidic cluster of residues in the E. coli PhoQ sensor domain (EDDDDAE149-154) is required for strong divalent cation binding in vitro and a normal response to Mg2+ deprivation in vivo (39). The wild-type sensor domain is stabilized with respect to urea denaturation specifically in the presence of divalent cations (including Mg2+ and Ca2+), suggesting that the binding energy directly stabilizes the protein. Replacing the negatively charged Asp and Glu residues in the cluster with noncharged Asn and Gln residues results in a protein that is no longer stabilized by divalent cations in vitro and is impaired in the ability to activate transcription of a reporter gene in vivo under conditions of limiting divalent cations (39). These results suggest that the acidic cluster serves as a ligand binding site for both Mg2+ and Ca2+. Although this interpretation may seem to be inconsistent with a dual-binding-site model, these results do not rule out the possibility that Mg2+ and Ca2+ can bind to residues in the acidic cluster at the same time, the possibility that there may be additional ligand binding sites, or the possibility that Mg2+ and/or Ca2+ can also repress PhoQ activity indirectly.

It is striking that only amino acids at position 48 with aromatic side chains render the protein significantly less sensitive to repression by Ca2+. One possible explanation for this is that the hydrophobic ring may participate in an interaction that interferes with a conformational switch to the repressed state. Alternatively, the bulk of the side chain may prevent an interaction that is necessary for formation of the repressed state. It is important to determine if these mutants can still bind Ca2+ to elucidate whether the defect is in detection or in transduction of the signal. A comparison of the Tyr48 mutant with the Phe48 mutant indicates that the hydroxyl group on the tyrosine ring is necessary for both the elevated activity of the Tyr48 mutant in the absence of divalent cations and repression in the presence of 3.0 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 3b). Although it may be tempting to speculate that the hydroxyl group in the wild-type threonine residue plays a similar role in activation and repression, several mutants containing amino acids that lack a hydroxyl group in their side chains display signaling phenotypes similar to that of the wild-type protein (Fig. 2). We also cannot rule out the possibility that the increased size and bulk of the tyrosine side chain allow the hydroxyl group to interact with a residue(s) that would not normally be close enough to interact with the wild-type threonine side chain.

Our results do not shed much light on the nature of the hyperactive phenotype displayed by the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ-T48I protein. Only a mutant with a Tyr48 substitution in the E. coli protein displayed a hyperactive phenotype reminiscent of the phenotype of the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ-T48I mutant, and the E. coli PhoQ-T48I mutant actually showed reduced activity. The difference in phenotypes displayed by the two PhoQ-T48I mutants is not the result of strain differences unrelated to the phoQ genes (Fig. 6) and is still observed when the mutation is present in the chromosomal phoQ gene (Fig. 4a and 5a). The nature of the phenotypic differences displayed by the analogous E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ-T48I mutants is not readily apparent as the two proteins are 86% identical overall and 100% identical in the region proximal to residue 48 (18). Also, the secondary structures of truncated wild-type and T48I mutant E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium sensor domain proteins are indistinguishable, as determined by circular dichroism spectroscopy (unpublished results). We propose a model in which Thr48 plays similar functional and/or structural roles in both PhoQ proteins, but the T48I mutation reveals subtle differences between the E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium proteins. Perhaps the isoleucine substitution at residue 48 in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ protein interacts with another part of the protein or alters the dimeric interface and affects the structure of PhoQ in a way that increases the net phosphotransfer to PhoP. In the E. coli protein, residue 48 may be slightly juxtaposed so that an isoleucine residue cannot similarly affect the structure. We note that these arguments are based on the lack of observed structural changes in the sensor domain fragments. We cannot rule out the possibility that the T48I mutation does have different structural effects in the context of the membrane-bound intact molecules.

The inability of the PhoQ-ΔSD mutant to fully activate transcription of a PhoP-dependent reporter gene indicates that the periplasmic sensor domain is required to direct formation of the active state of PhoQ. Since the protein is competent to perform autokinase and phosphoryl transfer reactions, the inability of the mutant to fully activate reporter expression is not due to a general defect in protein folding or function but rather is due to a specific effect on phospho-PhoP stability. Histidine kinases are dimeric molecules that utilize a transphosphorylation mechanism (33). Our results argue against a simple model in which the autokinase activity is regulated by a ligand-mediated dimerization mechanism and are consistent with a model in which extracellular Mg2+ reduces net phosphorylation of PhoP by interacting with the sensor domain of PhoQ to produce a conformation that destabilizes the phospho-PhoP bond. The presence of a phosphatase activity has been hypothesized for a number of histidine kinases (10, 16, 17, 40), including PhoQ (3). However, the mechanism of this activity is unclear. PhoQ could cleave the aspartyl-phosphate bond directly, releasing free orthophosphate, or PhoQ may stimulate a PhoP-resident autophosphatase activity. Alternatively, reverse transfer to PhoQ may predominate when extracellular concentrations of Mg2+ are high. Indeed, reverse transfer has been observed in the PhoP-PhoQ and OmpR-EnvZ systems (3, 7; unpublished results). Whatever the mechanism, our results indicate that removal of the sensor domain promotes formation of a phosphatase-activated state. Although reporter expression activation is severely compromised in the absence of Mg2+, it is not completely abolished by deletion of the sensor domain (reporter expression is still activated roughly sevenfold in the presence of the mutant). Thus, repression by extracellular Mg2+ consists of both sensor domain-dependent and sensor domain-independent elements, indicating that a simple model in which the enzymatic activities of PhoQ are regulated by a conformational change mediated solely by the binding of divalent cations to the sensor domain does not adequately describe the mechanism. An understanding of the nature of the sensor domain-independent component awaits further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI41566 to C.D.W., and additional funding was provided by the American Cancer Society and an institutional grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to the College of Physicians and Surgeons. A.G.R. was a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellow at Columbia University.

We thank Laura Hales and Eduardo Groisman for bacterial strains and plasmids and Howard Shuman, Max Gottesman, and David Figurski for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behlau, I., and S. I. Miller. 1993. A PhoP-repressed gene promotes Salmonella typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:4475-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, E. M. 1994. Homeostatic mechanisms regulating extracellular and intracellular calcium metabolism, p. 15-54. In J. P. Bilezikian, M. A. Levine, and R. Marcus (ed.), The parathyroid. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Castelli, M. E., E. García Véscovi, and F. C. Soncini. 2000. The phosphatase activity is the target for Mg2+ regulation of the sensor protein PhoQ in Salmonella. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22948-22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, C.-H., D. C. Han, C.-Y. Chen, Y.-F. Chen, and S. C. Winans. 1992. Genetic dissection of an Agrobacterium tumefaciens signal transduction system required for recognition of plant wounds. J. Bacteriol. 174:7033-7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchward, G., D. Belin, and Y. Nagamine. 1984. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene 31:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doering, D. S., and P. Matsudaira. 1996. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis at 40 of 76 positions in villin headpiece maps the F-actin binding site and structural features of the domain. Biochemistry 35:12677-12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta, R., and M. Inouye. 1996. Reverse phosphotransfer from OmpR to EnvZ in a kinase/phosphatase mutant of EnvZ (EnvZ·N347D), a bifunctional signal transducer of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1424-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García Véscovi, E. G., F. C. Soncini, and E. A. Groisman. 1996. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell 84:165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García Véscovi, E. G., Y. M. Ayala, E. DiCera, and E. A. Groisman. 1997. Characterization of the bacterial sensor protein PhoQ: evidence for distinct binding sites for Mg2+ and Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1440-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgellis, D., O. Kwon, P. DeWulf, and E. C. Lin. 1998. Signal decay through a reverse phosphorelay in the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32864-32869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunn, J. S., E. L. Hohmann, and S. I. Miller. 1996. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella virulence: a PhoQ periplasmic domain mutation results in increased net phosphotransfer to PhoP. J. Bacteriol. 178:6369-6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, C. M. Poduje, M. Daniel, J. S. Gunn, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, J. S. Gunn, B. Bainbridge, R. P. Darveau, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton, C. M., M. Aldea, B. K. Washburn, P. Babitzke, and S. R. Kushner. 1989. New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:4617-4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoch, J. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1995. Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Igo, M. M., A. J. Ninfa, J. B. Stock, and T. J. Silhavy. 1989. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a bacterial activator by a transmembrane receptor. Genes Dev. 3:1725-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamberov, E. S., M. R. Atkinson, P. Chandran, and A. J. Ninfa. 1994. Effect of mutation in Escherichia coli glnL (ntrB), encoding nitrogen regulator II (NRII or NtrB), on the phosphatase activity involved in bacterial nitrogen regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28294-28299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasahara, M., A. Nakata, and H. Shinegawa. 1992. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli phoP-phoQ operon. J. Bacteriol. 174:492-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasahara, M., A. Nakata, and H. Shinegawa. 1991. Molecular analysis of the Salmonella typhimurium phoN gene, which encodes nonspecific acid phosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 173:6750-6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kier, L. D., R. M. Weppelman, and B. N. Ames. 1979. Regulation of nonspecific acid phosphatases in Salmonella: phoN and phoP genes. J. Bacteriol. 138:155-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesley, J. A., and C. D. Waldburger. 2001. Comparison of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli PhoQ sensor domains. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30827-30833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Miller, S. I., W. P. Loomis, C. Alpuche-Aranda, I. Behlau, and E. Hohmann. 1993. The PhoP virulence regulon and live oral Salmonella vaccines. Vaccine 11:122-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, S. I., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. Constitutive expression of the PhoP regulon attenuates Salmonella virulence and survival within macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 172:2485-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, S. I., W. S. Pulkkinen, M. E. Selsted, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. Characterization of defensin resistance phenotypes associated with mutations in the phoP virulence regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 58:3706-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morales, V. M., A. Backman, and M. Bagdasarian. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson, D. L., and E. P. Kennedy. 1971. Magnesium transport in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 246:3042-3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panagiotidis, C. H., M. Reyes, A. Sievertsen, W. Boos, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Characterization of the structural requirements for assembly and nucleotide binding of an ATP-binding cassette transporter—the maltose transport system of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:23685-23696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinhart, R. A. 1988. Magnesium metabolism: a review with special reference to the relationship between intracellular content and serum levels. Arch. Intern. Med. 148:2415-2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes, M., and H. A. Shuman. 1988. Overproduction of MalK protein prevents expression of the Escherichia coli mal regulon. J. Bacteriol. 170:4598-4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Silver, S. 1978. Transport of cations and anions, p. 221-324. In B. P. Rosen (ed.), Bacterial transport. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 33.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stock, J. B., G. S. Lukat, and A. M. Stock. 1991. Bacterial chemotaxis and the molecular logic of intracellular signal transduction networks. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Chem. 20:109-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stock, J. B., A. J. Ninfa, and A. M. Stock. 1989. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:450-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokishita, S.-I., A. Kojima, H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 1991. Transmembrane signal transduction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli: functional importance of the periplasmic domain of the membrane-located kinase, EnvZ. J. Biol. Chem. 266:6780-6785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toyoda-Yamamoto, A., N. Shimoda, and Y. Machida. 2000. Genetic analysis of the signal-sensing region of the histidine protein kinase VirA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:939-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waldburger, C., and M. M. Susskind. 1994. Probing the informational content of Escherichia coli σ70 region 2.3 by combinatorial cassette mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1489-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldburger, C. D., and R. T. Sauer. 1996. Signal detection by the PhoQ sensor-transmitter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26630-26636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker, M. S., and J. A. DeMoss. 1993. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation catalyzed in vitro by purified components of the nitrate sensing system, NarX and NarL. J. Biol. Chem. 268:8391-8393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wick, M. J., C. V. Harding, N. J. Twesten, S. J. Normark, and J. D. Pfeiffer. 1995. The phoP locus influences processing and presentation of Salmonella typhimurium antigens by activated macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 16:465-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada, M., K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and A. Nakata. 1990. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli: properties of phoR deletion mutants and subcellular localization of PhoR protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 220:366-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]