Abstract

Substitution of one amino acid for another at the active site of an enzyme usually diminishes or eliminates the activity of the enzyme. In some cases, however, the specificity of the enzyme is changed. In this study, we report that the changing of a metal ligand at the active site of the NiFeS-containing carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) converts the enzyme to a hydrogenase or a hydroxylamine reductase. CODH with alanine substituted for Cys531 exhibits substantial uptake hydrogenase activity, and this activity is enhanced by treatment with CO. CODH with valine substituted for His265 exhibits hydroxylamine reductase activity. Both Cys531 and His265 are ligands to the active-site cluster of CODH. Further, CODH with Fe substituted for Ni at the active site acquires hydroxylamine reductase activity.

Rhodospirillum rubrum is able to grow with carbon monoxide as its energy source (3, 15), and the key enzyme for this metabolic capability, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), catalyzes the reversible oxidation of CO to CO2. CODH is encoded by the cooS gene, and the CODH dimer has five metal clusters (5, 6): a Fe4S4 cluster that bridges the two subunits and that is termed the D cluster, a pair of Fe4S4 clusters referred to as B clusters, and a pair of clusters referred to as C clusters. The C cluster constitutes the active site of the enzyme, and structures for the C clusters from R. rubrum and from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans have recently been reported (5, 6) and discussed (17). The C cluster from R. rubrum CODH is reported to contain NiFe4S4, while that from C. hydrogenoformans CODH is reported to contain NiFe4S5. In both cases, the Ni also is associated with a Fe3S4 unit and is bridged to a fourth Fe atom. It has been suggested that the C cluster from R. rubrum CODH contains a nonsubstrate CO ligand (12). Unless otherwise noted, the CODH referred to hereafter is the R. rubrum CODH or a variant of that enzyme. While the metabolic role of CODH is to catalyze conversion of CO to CO2, the enzyme is also reported to catalyze the production of formate (11). Menon and Ragsdale have reported a trace of hydrogenase activity by the clostridial CODH (19).

CODH variants with substitutions at several conserved cysteine and histidine residues were produced by site-directed mutagenesis of the cooS gene (21, 22). Analysis of these variants revealed that the H265V and C531A forms of CODH exhibit lower CO oxidation activity and altered spectroscopic properties (21, 22). Structural analysis revealed that amino acid residues 265 and 531 are in the immediate vicinity of the C cluster (6). Analysis of the activities of these variant forms revealed that the C531A CODH is an uptake hydrogenase (H2 → 2H+ + 2e−). Furthermore, we discovered that the H265V CODH and Fe-substituted CODH catalyze a completely unexpected reaction, the reduction of NH2OH to NH3 and H2O.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental conditions.

All experiments were performed anaerobically (<2 ppm O2) in a Vacuum Atmospheres Dri-Lab glove box (model HE-493) unless otherwise noted.

Preparations of chemicals.

Metal-free MOPS buffer (3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid; U.S. Biochemicals; pH 7.5) used for enzyme purifications and kinetics experiments was obtained by passing stock MOPS buffer through a metal-chelating column of Chelex-100 cation exchange resin (Bio-Rad). Stock solutions of hydroxylamine (NH2OH; Sigma), methylhydroxylamine (CH3NHOH; Aldrich), hydrazine (NH2NH2; Sigma), hydroxyquinone (Kodak), imidazole (Sigma), and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl; Fisher) were prepared in the metal-free MOPS buffer (1 M; pH 7.5) anaerobically.

Mutant construction.

Site-specific mutagenesis of R. rubrum cooS to obtain CODH with replacement of residues Cys531 and His265 with Ala and Val was described previously (21, 22).

Cell culture and purification.

Culture of Ni-containing and Ni-deficient wild-type (wt), C531A, and H265V cells was performed according to the established procedures (2, 3, 7, 21, 22). Purification of the wt and variant CODHs followed previously established protocols (12, 21, 22)

Protein assays.

Protein concentrations were determined colorimetrically with bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) as a standard (20). BSA solution was standardized against carbonic anhydrase prior to use.

Metal substitutions.

Incorporation of metals (Fe, Zn, and Co) into Ni-deficient CODH was performed in accordance with the previously published method (8, 13).

CO and H2 oxidation activity assays.

CO and H2 oxidation activities were determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the rate of methyl viologen (MV) reduction in the assay solutions containing metal-free MOPS (100 mM; pH 7.5), EDTA (10 μM), and MV (10 mM) (3, 18); assay mixtures were saturated with either CO or H2 by bubbling them with 100% CO or H2 immediately before initiating the reaction by addition of the enzyme. Activities are expressed as micromoles of CO or H2 oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

Hydroxylamine reductase activity assay.

Hydroxylamine (NH2OH) reductase activities were determined by monitoring the NH2OH-dependent oxidation of MV spectrophotometrically at 578 nm. Assays were performed anaerobically under an N2 atmosphere in a 1.0-ml assay mixture containing metal-free MOPS (100 mM; pH 7.5), EDTA (10 μM), and MV (10 mM). Unless otherwise noted, 100 mM NH2OH was present in the assay. For the assay, a specific amount of purified CODH sample was added to the anaerobically prepared assay mixture in cuvettes (1.5 ml), and this solution was then poised with sodium dithionite (DTH) to reduce MV (in most assays, MV in the assay solution was reduced to give an absorbance at 578 nm [A578] of near 1). Once the assay solution was properly poised, NH2OH was added to the vial and the vial was immediately placed into the spectrophotometer. Rates were recorded on a Shimadzu 1605 dual-beam spectrophotometer. The overall decrease in A578 (oxidation of reduced MV) was monitored for 20 s. This slope was then used to calculate the rate of NH2OH reduction performed by the enzyme. A control assay that lacked enzyme was also performed, and there was no significant decrease in A578. Activities are expressed as micromoles of NH2OH reduced per minute per milligram of protein.

Determination of hydroxylamine-dependent ammonia production.

Twenty-milliliter samples of the reaction assay mixture were prepared anaerobically as described above and sealed with airtight, rubber stoppers. Note that the sealed assay mixtures contained minimal headspace, thereby decreasing the amount of NH3 diffusion from the solution to the atmosphere. The reactions were initiated by addition of enzyme to the sealed solutions and allowed to continue for 60 min, at which point further NH2OH reduction was stopped by heating the reaction mixture to 100°C.

For quantification of final NH3 levels, the reaction mixtures listed above were analyzed with a Braun+Luebbe Auto Analyzer II for NH3 analysis at the University of Georgia. To determine the final levels of NH2OH present after the reactions, NH2OH assays were performed using the method established by Korpela and Makela (16).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Conversion of CODH into H2 uptake hydrogenase.

Table 1 shows that C531A CODH exhibits relatively high uptake hydrogenase (H2 oxidation) activity compared to both wt and H265V CODH. In contrast to the high rates of H2 oxidation exhibited by C531A CODH, this enzyme has a minimal CO oxidation activity compared to wt CODH (22). Table 1 also shows that the hydrogenase activity was enhanced by incubation of C531A CODH with CO. The maximum activity of the uptake hydrogenase C531A CODH is close to that seen in NiFe hydrogenase (22).

TABLE 1.

H2 uptake hydrogenase activity of wt and variant forms of R. rubrum CODHa

| CODH | H2 uptake hydrogenase activity (μmol of H2 oxidized min−1 mg of protein−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| As isolated | H2 treated | CO treated | |

| wt | |||

| Ni deficient | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

| Ni containing | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| H265V | |||

| Ni deficient | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| Ni containing | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

| Ni-containing C531A | 8.28 ± 0.98 | 8.92 ± 0.81 | 21.04 ± 0.55 |

Determinations of uptake hydrogenase activities are described in Materials and Methods. Pretreatment of H2 and CO was performed by incubation of CODH samples with H2 or CO for 30 min. H2- and CO-treated CODH samples were reisolated by anaerobic gel filtration on a 1- by 5-cm Sephadex G-25 column. Each assay was performed three times. The final enzyme concentrations used in these assays were 10 μg/ml. Values are means ± standard deviations.

The recently solved X-ray crystal structures of R. rubrum and C. hydrogenoformans CODHs show that Cys531 is coordinated directly to the Ni site (5, 6). It is therefore expected that a replacement of Cys531 with Ala could change the ligand environment of the Ni site. Altering the Ni environment of the CODH C cluster by replacement of Cys531 with Ala produces a variant enzyme with H2 uptake (H2 as a substrate) hydrogenase activity.

It was determined that unlike what was found with hydrogenases, H2 incubation prior to measurement of activity did not significantly increase the uptake hydrogenase activity. However, CO preincubation dramatically increased the activity. These results suggest that a ligation of CO on the C cluster of C531A CODH provides a more favorable kinetic or thermodynamic environment for H2 oxidation. A ligand CO is found in the Fe site of the [NiFe] center of NiFe hydrogenase (R. P. Happe, W. Roseboom, A. J. Pierik, S. P. J. Albracht, and K. A. Bagley, Letter, Nature 385:126, 1997). It is, therefore, possible to suggest that a ligand CO is also required for the H2 uptake hydrogenase activity of C531A CODH, much in the same manner as it is required for the H2 uptake hydrogenase activity in [NiFe] hydrogenase.

Conversion of CODH into hydroxylamine reductase.

Hydroxylamine (NH2OH)-dependent MV oxidation by forms of CODH was examined, and the results are shown in Table 2. Ni-containing wt and C531A CODHs show a low rate of NH2OH reduction. However, the NH2OH reductase activity of Ni-deficient wt CODH is approximately threefold higher than that of Ni-containing wt CODH, suggesting that the novel hydroxylamine reductase activity of H265V CODH is independent of the presence of Ni in the C cluster. H265V CODH, in both its Ni-deficient and Ni-containing forms, shows relatively high NH2OH reductase activity compared to any other CODH studied. Metal-substituted forms of wt CODH were tested, and it was found that the incorporation of Fe into Ni-deficient wt CODH increases the rate of NH2OH reduction approximately sixfold (Table 2). However Zn- and Co-incorporated CODHs show only residual NH2OH reduction activity (data not shown). Pretreatment of the enzyme with either H2 or CO does not dramatically affect the rate of NH2OH reduction of any form of the enzyme.

TABLE 2.

Hydroxylamine reductase activities of wt and variant forms of R. rubrum CODHa

| CODH | Hydroxylamine reductase activity (μmol of NH2OH reduced min−1 mg of protein−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| As isolated | H2 treated | CO treated | |

| wt | |||

| Ni containing | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.19 |

| Ni deficient | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 4.0 ± 2.5 | 0.3 ± 0.14 |

| Fe incorporated | 20.5 ± 0.9 | 23.0 ± 1.8 | 16.3 ± 0.4 |

| H265V | |||

| Ni containing | 28.8 ± 4.6 | 29.7 ± 1.1 | 26.2 ± 0.8 |

| Ni deficient | 33.4 ± 1.4 | 29.9 ± 0.1 | 25.3 ± 2.0 |

| C531A | |||

| Ni containing | 0.85 ± 0.1 | 1.23 ± 0.1 | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

| Ni deficient | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.13 |

Pretreatment of CODH samples with H2 and CO was as described for Table 1. The final enzyme concentrations of CODHs in this experiment are 10 μg/ml. Determination of hydroxylamine reduction activity of CODH is described in Materials and Methods. Assay mixtures contained 100 mM NH2OH, and each assay was performed three times. Values are means ± standard deviations.

Table 3 shows the rates of MV oxidation in the presence of selected analogs of NH2OH by H265V CODH. H265V CODH also oxidizes MV in the presence of methylhydroxylamine (CH3NHOH) and hydroxyquinone. Other chemical analogs of NH2OH, including hydrazine (NH2NH2), imidazole, and ammonia (NH3), were neither reduced by CODH nor inhibitory to the reduction of NH2OH by H265V CODH. Table 4 shows the stoichiometry of hydroxylamine-dependent ammonium production by H265V CODH. NH3 is produced in a 1:1 ratio with the loss of NH2OH.

TABLE 3.

CODH-dependent reduction of hydroxylamine analogs and other chemical compoundsa

| Chemical(s) | Rate of MV oxidation (μmol of chemical reduced min−1 mg of protein−1) by Ni-deficient:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| wt CODH | H265V CODH | |

| NH2OH | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 25.7 ± 0.1 |

| CH3NHOH | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 19.5 ± 0.4 |

| NH2NH2 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Hydroxyquinone | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.9 |

| Imidazole | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| NH4Cl | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| NH2OH + NH2NH2 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | 24.3 ± 0.1 |

| NH2OH + imidazole | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 25.3 ± 0.2 |

| NH2OH + NH4Cl | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 24.9 ± 0.3 |

Assay and experimental conditions were identical to those described for Table 2 except that other chemical compounds besides NH2OH were used. Final concentrations of the chemicals in the assay mixtures were 50 mM. Final concentrations of CODH in the assay mixtures were 13 μg/ml. Each assay was performed three times. Values are means ± standard deviations.

TABLE 4.

Stoichiometry of hydroxylamine-dependent ammonia production by H265V CODH and wt CODHa

| Sample | Level (μmol ml of solution−1) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NH2OH added | NH3 produced | Final NH2OH | |

| Without enzyme | 5.0 ± 0.1 | <0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.3 |

| H265V CODH | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| wt CODH | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

Enzyme samples were prepared and NH2OH levels were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Concentrations of enzymes used in these experiments were the same as those reported in Table 1. Assay mixtures were incubated for 60 min. Values are means ± standard deviations.

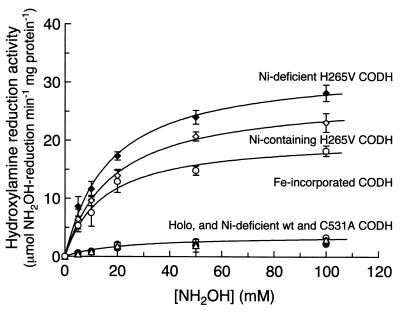

Hydroxylamine reductase activity in several variant forms of CODH was observed and measured. Figure 1 provides a comparison of the rates of hydroxylamine reduction by several of these variants, including Ni-containing and Ni-deficient forms of H265V, C531A, and wt CODHs and Fe-substituted wt CODH, as a function of NH2OH concentration. The highest rate of hydroxylamine reduction was observed in the Ni-deficient form of H265V CODH, and the Km for NH2OH reduction by this form of the enzyme, estimated by replotting these data, was found to be ∼16 mM NH2OH; it is unlikely that this activity is physiologically significant in the cell.

FIG. 1.

Substrate dependence of hydroxylamine reduction by various forms of CODH. Hydroxylamine (NH2OH) reductase activities with variable concentrations of NH2OH were monitored as described in Materials and Methods. Km for NH2OH was determined to be 17.4 ± 3.5 mM for all forms of CODH. The concentration of enzyme used in assays was 10 μg/ml. Apo-H265V, Ni-deficient H265V; Holo-H265V, Ni-containing H265V.

The NH2OH reductase activity exhibited by CODH was previously undetected, and this activity is greatly enhanced by replacement of His265 with Val or by incorporation of Fe into the Ni site of the C cluster. Ni is not necessary for the hydroxylamine reductase activity of H265V CODH, although CO oxidation by CODH requires that Ni be present. It is therefore reasonable to propose that the catalytic process of NH2OH reduction by H265V CODH is different from the CO oxidation process carried out by CODH. It is interesting that benzoyl-coenzyme A reductase also exhibits NH2OH reduction, but this enzyme is a molybdopterin-containing protein and unlikely to be similar to the NiFeS CODH (1).

A reduced viologen dye (either MV or benzyl viologen [BV]) was required for hydroxylamine reductase activity of H265V CODH, suggesting that viologen serves as an electron donor for the reduction of NH2OH by H265V CODH in vitro. The Km values for MV and BV are similar, near 0.2 mM, and the Vmax of hydroxylamine reductase activity varied slightly with MV, implying that MV supports approximately 10% higher activity than BV (data not shown). The stimulatory effect of viologen for the CO oxidation and CO2 reduction activities of wt CODH has also been reported, and it has been suggested that viologen facilitates the transport of electrons between CODH and the outer electron acceptor (redox buffer in vitro) (10). Therefore, it can be postulated that viologen acts in a similar manner in the process of NH2OH reduction as well.

Fe-CODH was also tested for hydroxylamine reductase activity. While Ni-deficient CODH had hydroxylamine reductase activity of approximately 3 μmol of NH2OH reduced min−1 mg of protein−1, Fe-CODH showed an activity of approximately 20 μmol of NH2OH reduced min−1 mg of protein−1, or nearly six times that of the Ni-deficient CODH. Thus, in addition to ligand substitution, the incorporation of Fe in place of Ni into the active site alters substrate specificity in CODH.

The crystal structures of both R. rubrum and C. hydrogenoformans CODHs show that His265 coordinates an Fe atom of the cluster (5, 6). As purified, the H265V variant has a low Ni content but only a slightly decreased Fe content (21). The CO oxidation rate of as-purified H265V was reported as only approximately 2.5 μmol of CO oxidized min−1 mg of protein−1 compared to 7,000 μmol of CO oxidized min−1 mg of protein−1 for wt CODH. Further, electron paramagnetic resonance studies of H265V CODH reveal changes in the spectral features attributed to the C cluster. These biochemical and spectroscopic results from analyses of H265V CODH further support the idea that the substitution of His265 changes the environment of the active-site C cluster.

Effects of cyanide and acetylene on hydroxylamine reductase activity.

Cyanide (CN−) is a potent inhibitor of CODH activity (9, 13). Cyanide does not show any stimulatory or inhibitory effects on NH2OH reduction at concentrations less than 500 μM (data not shown). Therefore, it is concluded that CN− does not have any effect on the rate of NH2OH reduction by H265V CODH. At high concentrations of CN− (>5 mM for a 25-min incubation) in the presence of DTH, the hydroxylamine reductase activity of H265V CODH was inhibited. However, we have observed that CN− degrades CODH in the presence of high concentrations of CN− and DTH (22). Acetylene is a known inhibitor of Ni hydrogenases (14). Treatment of CODH and its variants with acetylene resulted in modest (less than twofold) stimulation of H2 and CO oxidation and also resulted in inhibition of NH2OH reduction (data not shown)

It is possible that further manipulation of the C-cluster environment (i.e., ligand variations), in conjunction with heterometal substitution, can produce CODH variants with even higher levels of hydroxylamine reductase activity than those reported in this work.

Relationship of CODH to HCP.

Garavelli and coworkers have noted the similarity between the active-site clusters of CODH and the hybrid cluster protein (HCP); this similarity is interesting in light of the observed NH2OH reduction activity by Fe-CODH (J. S. Garavelli, H. Z. Huang, and D. J. Miller, Abstr. Protein Sci. Meet., abstr. 131-M, 2000). The HCP active site contains four Fe atoms, while the CODH C cluster contains one Ni atom and multiple Fe atoms (4). As discussed above, when an Fe atom replaces the Ni atom of the CODH C cluster, the enzyme acquires enhanced NH2OH reductase activity. These observations raise the possibility that the HCP might serve as a hydroxylamine reductase, a hypothesis recently confirmed (23).

In conclusion, it is evident that the substrate specificities of H265V CODH, C531A CODH, and Fe-substituted CODH have been altered by only a single active-site ligand or metal substitution, creating enzymes nearly as competent in catalysis as their native counterparts.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. P. Roberts and R. L. Kerby for discussions.

This work was supported in part by U.S. Department of Energy Basic Energy Sciences grant DE-FG02-87ER13691 to P.W.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boll, M., and G. Fuchs. 1995. Benzoyl-coenzymeA reductase (dearomatizing), a key enzyme of anaerobic aromatic metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 234:921-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonam, D., and P. W. Ludden. 1987. Purification and characterization of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, a nickel, zinc, iron-sulfur protein, from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Biol. Chem. 262:2980-2987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonam, D., S. A. Murrell, and P. W. Ludden. 1984. Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 159:693-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, S. J., C. D. Garner, W. R. Hagen, P. F. Lindley, and S. Bailey. 2000. Hybrid-cluster protein (HCP) from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) at 1.6 Å resolution. Biochemistry 39:15044-15054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbek, H., V. Svetlitchnyi, L. Gremer, R. Huber, and O. Meyer. 2001. Crystal structure of a carbon monoxide dehydrogenase reveals a [Ni-4Fe-5S] cluster. Science 293:1281-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drennan, C. L., J. Heo, M. D. Sintchak, E. Schreiter, and P. W. Ludden. 2001. Life on carbon monoxide: X-ray structure of Rhodospirillum rubrum Ni-Fe-S carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11973-11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensign, S. A., D. Bonam, and P. W. Ludden. 1989. Nickel is required for the transfer of electrons from carbon monoxide to the iron-sulfur centers of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochemistry 28:4968-4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensign, S. A., M. J. Campbell, and P. W. Ludden. 1990. Activation of the nickel-deficient carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum: kinetic characterization and reductant requirement. Biochemistry 29:2162-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ensign, S. A., M. R. Hyman, and P. W. Ludden. 1989. Nickel-specific, slow-binding inhibition of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum by cyanide. Biochemistry 28:4973-4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heo, J., C. M. Halbleib, and P. W. Ludden. 2001. Redox-dependent activation of CO dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7690-7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heo, J., L. Skjeldal, C. R. Staples, and P. W. Ludden. 30April2002, posting date. CO dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum produces formate. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. [Online.] http://link.springer-ny.com/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Heo, J., C. R. Staples, C. M. Halbleib, and P. W. Ludden. 2000. Evidence for a ligand CO that is required for catalytic activity of CO-dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochemistry 39:7956-7963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heo, J., C. R. Staples, J. Telser, and P. W. Ludden. 1999. Rhodospirillum rubrum CO-dehydrogenase. Part 2. Spectroscopic investigation and assignment of spin-spin coupling signals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:11045-11057. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyman, M. R., and D. J. Arp. 1987. Acetylene is an active-site-directed, slow-binding, reversible inhibitor of Azotobacter vinelandii hydrogenase. Biochemistry 26:6447-6454. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerby, R. L., P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1995. Carbon monoxide-dependent growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 177:2241-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korpela, T. K., and M. J. Makela. 1981. Spectrophotometric measurement of hydroxylamine and its O-alkyl derivatives. Anal. Biochem. 119:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl, P. A. 2002. The Ni-containing carbon monoxide dehydrogenase family: light at the end of the tunnel? Biochemistry 41:2097-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McTavish, H., L. A. Sayavedra-Soto, and D. J. Arp. 1996. Comparison of isotope exchange, H2 evolution, and H2 oxidation activities of Azotobacter vinelandii hydrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1294:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon, S., and S. W. Ragsdale. 1996. Unleashing hydrogenase activity in carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase and pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase. Biochemistry 35:15814-15821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, P. K., R. I. Krohn, G. T. Hermanson, A. K. Mallia, F. H. Gartner, M. D. Provenzano, E. K. Fujimoto, N. M. Goeke, B. J. Olson, and D. C. Klenk. 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spangler, N. J., M. R. Meyers, K. L. Gierke, R. L. Kerby, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1998. Substitution of valine for histidine 265 in carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum affects activity and spectroscopic states. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4059-4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staples, C. R., J. Heo, N. J. Spangler, R. L. Kerby, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1999. Rhodospirillum rubrum CO-dehydrogenase. Part 1. Spectroscopic studies of CODH variant C531A indicate the presence of a binuclear [FeNi] cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:11034-11044. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfe, M. T., Y. Heo, J. S. Garavelli, and P. W. Ludden. 2002. Hydroxylamine reductase activity of the hybrid cluster protein from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:5898-5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]