Abstract

Phages of the P335 group have recently emerged as important taxa among lactococcal phages that disrupt dairy fermentations. DNA sequencing has revealed extensive homologies between the lytic and temperate phages of this group. The P335 lytic phage φ31 encodes a genetic switch region of cI and cro homologs but lacks the phage attachment site and integrase necessary to establish lysogeny. When the putative cI repressor gene of phage φ31 was subcloned into the medium-copy-number vector pAK80, no superinfection immunity was conferred to the host, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCK203, indicating that the wild-type CI repressor was dysfunctional. Attempts to clone the full-length cI gene in Lactococcus in the high-copy-number shuttle vector pTRKH2 were unsuccessful. The single clone that was recovered harbored an ochre mutation in the cI gene after the first 128 amino acids of the predicted 180-amino-acid protein. In the presence of the truncated CI construct, pTRKH2::CI-per1, phage φ31 was inhibited to an efficiency of plaquing (EOP) of 10−6 in NCK203. A pTRKH2 subclone which lacked the DNA downstream of the ochre mutation, pTRKH2::CI-per2, confirmed the phenotype and further reduced the φ31 EOP to <10−7. Phage φ31 mutants, partially resistant to CI-per, were isolated and showed changes in two of three putative operator sites for CI and Cro binding. Both the wild-type and truncated CI proteins bound the two wild-type operators in gel mobility shift experiments, but the mutated operators were not bound by the truncated CI. Twelve of 16 lytic P335 group phages failed to form plaques on L. lactis harboring pTRKH2::CI-per2, while 4 phages formed plaques at normal efficiencies. Comparisons of amino acid and DNA level homologies with other lactococcal temperate phage repressors suggest that evolutionary events may have led to inactivation of the φ31 CI repressor. This study demonstrated that a number of different P335 phages, lytic for L. lactis NCK203, have a common operator region which can be targeted by a truncated derivative of a dysfunctional CI repressor.

Bacteriophages continue to be a significant economic problem for the dairy industry. While naturally occurring defenses, the rotation of starter cultures, and improved sanitation measures have been used to combat the problem, phages continue to evolve to overcome host defense mechanisms. The P335 group, one of three major phage groups that remain problematic for Lactococcus lactis in dairy fermentations, includes both lytic and temperate members (21). Sequence homologies have revealed close links and evidence of DNA exchanges between lytic and temperate P335 phages (3, 8, 9, 12, 20, 28, 33, 37, 44, 46). Furthermore, new, recombinant lytic phages have been recovered after acquisition of chromosomal DNA regions from their lactococcal hosts (3, 12, 33).

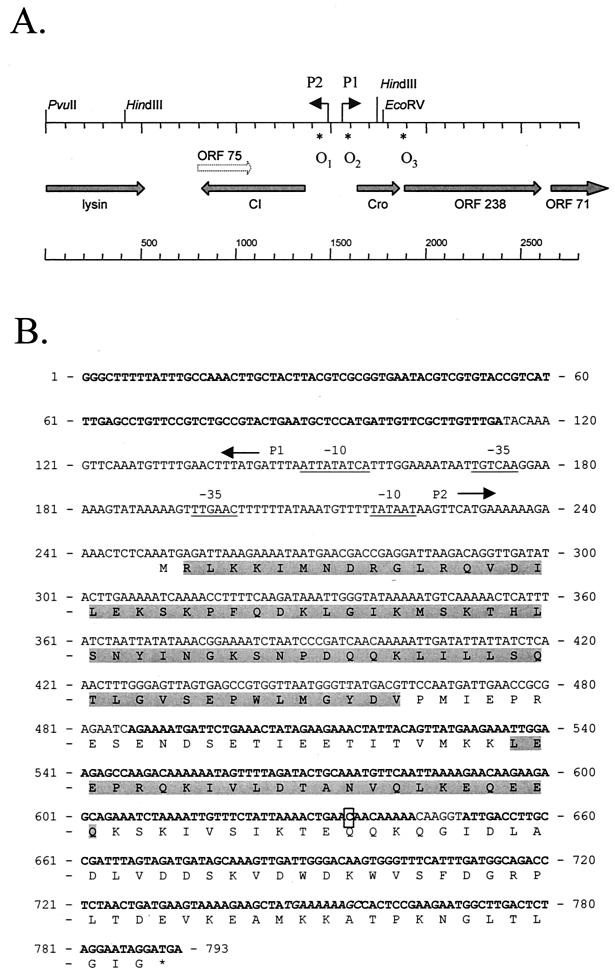

The lactococcal bacteriophage φ31 is a small-isometric-headed, cohesive-ended, lytic phage of the P335 group with a double-stranded DNA genome of 31.9 kb (1). Sequencing over 14.3 kb of phage φ31 has defined the following gene clusters: a locus involved in sensitivity to the phage resistance mechanism AbiA (10); a late promoter region and a transcriptional activator of the promoter (11, 37, 44-46); the phage replication module (28, 35); part of the lysis module (28); and a genetic switch region (28). The genetic switch region encodes two divergent promoters, P1 and P2, and homologues to cI and cro genes of temperate phages shown in Fig. 1A. Open reading frame (ORF) 238, downstream of the cro gene, has amino acid-level homology to putative antirepressors from the temperate L. lactis phage TP901-1 and Streptococcus thermophilus phage TP-J34. Lack of an integrase gene and an attachment site explains the lytic life cycle of phage φ31 (28). The objective of the present study was to investigate the functionality of the phage φ31 CI repressor and determine whether or not the repressor could be constitutively overexpressed in L. lactis to retard infection by phages of the P335 group. Interestingly, the CI repressor of this obligatorily lytic phage failed to provide superinfection immunity when cloned and expressed from a medium-copy-number vector. This finding was unexpected, as most CI-like repressors, expressed from one gene copy in an integrated prophage, will retard superinfecting phage. Truncated versions of CI were highly effective and acted, surprisingly, across many different phages of the P335 group.

FIG. 1.

(A) Organization of the genetic switch region of phage φ31. (B) Sequence of the cI gene of φ31showing the translated cI ORF and divergent promoters P1 and P2. Arrows indicate the direction of the promoters (the −10 and −35 sequences are underlined). The boxed nucleotide C was mutated to T in pTRKH2::CI-per1. Bold type in the nucleic acid sequence indicates DNA homology (identities of 83% or higher) to phages BK5-T, bIL309, Tuc2009, phi LC3, and r1t (bp 1 to 114); TP901-1 and bIL285 (bp 487 to 603); bIL286 (bp 539 to 782); Tuc2009 and phi LC3 (bp 539 to 575); or BK5-T, r1t, Tuc2009, phiLC3, bIL309, and bIL312 (bp 749 to 793). The two highlighted regions in the amino acid sequence show homology to phages TP901-1, PVL, and phiO12505 (residues RLKK…GYDV) and to phages bIL285, bIL286, TP901-1, BK5-T, Tuc2009, and r1t (residues LEEP…QEEQ). The sequence represented in italics (TGAAAAAAGC) defines the beginning of a homologous region between φ31 cI and nonrepressor sequences found in P335 temperate phages (see the Discussion for details).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophages.

Table 1 lists the strains, plasmids, and bacteriophages used in this work. L. lactis subsp. lactis NCK203 was grown at 30°C in M17 medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.5% glucose (M17G) and erythromycin at a concentration of 1.5 μg/ml, as needed. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (38) or brain heart infusion medium (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 150 μg of erythromycin/ml, as needed. Phages were propagated on L. lactis subsp. lactis NCK203, and titers were determined by standard methods (42). Efficiencies of plaquing (EOPs) were calculated by dividing the number of PFU per milliliter for each phage plated on NCK203 containing a CI construct by the number of PFU per milliliter on NCK203 (pTRKH2 or pAK80). Plaque sizes were determined as the average size of 10 individual plaques. Individual plaques were propagated by picking into 3.5 to 5 ml of M17G containing 10 mM CaCl2 and inoculation with 35 to 50 μl of an overnight culture of L. lactis NCK203. The tubes were incubated at 30°C until lysis and then centrifuged to pellet debris. Phage lysates were then filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filter (Nalgene Co., Rochester, N.Y.).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, bacteriophages, and primers

| Strain, plasmid, phage, or primer | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| L. lactis subsp. lactis NCK203 | Propagating host for phages | 17, 39 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 | Transformation host | 14 |

| E. coli MC1061 | Transformation host | 18 |

| E. coli TOP10 | Transformation host | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTRKH2 | E. coli gram-positive cloning vector, 6.7 kb, Emr | 36 |

| pAK80 | E. coli gram-positive cloning and promoter probe vector, 11 kb, Emr | 19 |

| pSMBI 1 (designated pAK80::CI in text) | pAK80 + 907-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cl-XhoI-P1 and cI-BamHI-P2 | 28 |

| pTRK676 | pTRKH2 + 907-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI-BamHI-P2. Encodes full-length CI repressor | This study |

| pTRK677 (designated pTRKH2::CI-per1 in text) | Mutated pTRK676 (cI gene with an ochre point mutation) | This study |

| pTRK678 (designated pTRKH2::CI-per2 in text) | pTRKH2 + 571-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI sub 2-BamHI | This study |

| pTRK679 | pTRKH2 + 517-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI sub 3-BamHI | This study |

| pTRK680 | pTRKH2 + 469-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI sub 4-BamHI | This study |

| pTRK681 | pTRKH2 + 424-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI sub 5-BamHI | This study |

| pTRK728 (designated pAK80::CI-per 1 in text) | pAK80 + 907-bp pTRK677 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI-BamHI-P2 | This study |

| pTRK729 (designated pAK80::CI-per2 in text) | pAK80 + 571-bp φ31 PCR fragment from primers cI-XhoI-P1 and cI sub 2-BamHI | This study |

| Phages | ||

| φ31 | P335 group phage | 1 |

| φ31.1 | P335 group phage, recombinant variant of φ31 | 12 |

| φ31.2 | P335 group phage, recombinant variant of φ31 | 12 |

| ul36 | P335 group phage | 33 |

| ul37 | P335 group phage, recombinant variant of ul36 | 33 |

| Q30 | P335 group phage | 32 |

| Q33 | P335 group phage | 32 |

| Q36 | P335 group phage | 32 |

| mm210a | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| mm210b | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| A1 | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| B1 | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| CS | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| D1 | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| φ48 | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| φ50 | P335 group phage | Rhodia, Inc. |

| Primersb | ||

| cI-XhoI-1 (81) | GGC CGC TCG AGC CTG TTC CGT CTG CCG | |

| cI-BamHI-2 | TAG TAG GAT CCT TTT GGG AGA GAT AAA GCG CC | |

| cI sub 2-BamHI (621) | AGC TGG ATC CTT ATT CAG TTT TAA TAG | |

| cI sub 3-BamHI (564) | TAG AGG ATC CTT AAA CAT TTG CAG TAT CTA | |

| cI sub 4-BamHI (516) | TAG AGG ATC CTT ACT TCA TAA CTG TAA TAG | |

| cI sub 5-BamHI (471) | TAG AGG ATC CTT ATG ATT CTC GCG GTT CAA | |

| cI sub 6-BamHI (430) | ATG CGG ATC CTC ACG GCT CAC TAA CT | |

| P1-forward (282) | CGC GGA TCC CAA CCT GTC TTA ATC | |

| P1-reverse (17) | CGC CTG CAG GCT TTT TAT TTG CCA | |

| cI-extend (488) | AAT GAT TGA ACC GCG AGA ATC AG | |

| 75-right (673) | GTA TTG ACC TTG CCG ATT TAG TAG AT | |

| O1 left (241) | CTT TAA TCT CAT TTG AGA GTT T | |

| O1 right (174) | TAT CAT TTG GAA AAT AAT TGT C | |

| O2 left (154) | TGA CAA TTA TTT TCC AAA TGA T | |

| O2 right (99) | GCC GTA CTG AAT GCT CCA TGA T | |

| O3 left | GCT ACA GAA CTT CTT GGT ATT A | |

| O3 right | GTT TTC GTT TTG TGT GAT TGT A | |

| CI NcoI (271) | GAT CCC ATG GCT ATG AGA TTA AAG AAA ATA ATG |

Emr, erythromycin resistance.

The base pair position for the 3′-terminal nucleotide of primers from the sequence shown in Fig. 1 is shown in parentheses. Underlined portions of sequences represent restriction enzyme recognition sites in primers.

DNA isolation.

E. coli plasmid DNA was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) or by standard alkaline lysis procedures (38). L. lactis plasmid DNA was isolated from 1.5 ml of overnight cultures using the Perfectprep Plasmid Mini kit (Eppendorf Scientific Inc., Westburn, N.Y.) following the manufacturer's instructions, except that 1 mg of powdered lysozyme was added after the addition of solution I. The tubes were incubated for 15 min at 37°C before the addition of solution II. Genomic L. lactis and bacteriophage DNA was isolated as described previously (12).

PCR and DNA manipulations.

PCR products were generated by using Taq DNA polymerase or the Expand High-Fidelity PCR System obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.) as directed by the manufacturer. PCR primers (listed in Table 1) were designed using Primer Designer software (Scientific and Educational Software, Durham, N.C.) and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa). Reactions were performed using a PCR Express thermal cycler (Hybaid, Middlesex, United Kingdom) or a Perkin-Elmer model 2400 GeneAmp PCR system (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) set at an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 5 min and then 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min. PCR products were purified by using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen).

Restriction endonuclease digestions were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (38). For gene cloning, DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gel slices with the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ligations were carried out using the Fast-Link DNA ligation and screening kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.). Electroporation of E. coli and L. lactis cells was performed as described previously (12). Competent TOP10 cells were transformed by following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.).

In situ gel hybridizations were performed as described by Le Bourgeois et al. (23). Briefly, agarose gels were treated with NaOH to denature DNA fragments, neutralized, and then dried. [α-32P]dCTP-labeled probes were hybridized directly to the dried agarose gels in a hybridization oven (Robbins, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Probes were prepared from PCR fragments using the Multiprime DNA labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, N.J.), following the manufacturer's instructions, and purified using NucTrap Probe purification columns (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.).

DNA sequencing was performed at Davis Sequencing LLC (Davis, Calif.) from double-stranded plasmid DNA or PCR fragments amplified from phage DNA. DNA sequences were aligned using DNASIS for Windows (Hatachi Software, San Bruno, Calif.) or MultAlin software (7). The DNA sequence was further analyzed using Clone Manager software (Scientific and Educational Software). DNA homology searches were performed with the BlastN and BlastP programs available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST. Alignment of predicted repressor proteins was performed at the CMBI Clustal W server at www.cmbi.kun.nl/bioinf/tools/clustalw.shtml.

Gel mobility shift assays.

Gel mobility shift assays were performed as described previously (46). Separate PCR products containing one of the three operator regions, O1, O2, or O3, were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and end labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim) and [γ-32P]ATP (NEN, Boston, Mass.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Labeled probe fragments were then purified using NucTrap Probe purification columns (Stratagene). DNA template for transcription-translation of CI was prepared by cloning PCR products of the wild-type and mutated cI genes into the Novagen (Madison, Wis.) cloning vector pCITE-4a-c(+), using the NcoI and BamHI cloning sites in the vector. Insert fragments were amplified from φ31 DNA (for the wild-type cI) or from pTRKH2::CI-per1 (for the mutated cI) using the cI NcoI and cI-BamHI-2 primers (Table 1). The pCITE clones were sequenced to confirm that the inserts were in the proper reading frame for translation. Plasmid DNA from the clones was transcribed and translated using the Single-Tube Protein System 3 from Novagen according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein was used directly for DNA binding as described previously (46). Samples were run on a 5% polyacrylamide gel at 115 V.

RNA isolation and hybridization.

Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) as described previously (9). RNA hybridizations using the Bio-Dot-SF apparatus and a Zeta-probe membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) were accomplished according to the manufacturer's directions. Single-stranded DNA probes were prepared using T4 polynucleotide kinase (GIBCO-BRL) to end label oligonucleotides, and double-stranded probes were prepared from PCR products with the multiprime DNA labeling kit as described above.

RESULTS

Cloning and expression of the cI gene.

The L. lactis phage φ31 cI gene was cloned previously into the medium-copy-number vector pAK80, creating pSMBI1 (henceforth designated pAK80::CI) for use in studies of the genetic switch region of phage φ31 (28). When plasmid pAK80::CI was transformed into NCK203, no effect on the EOP of phage φ31 was observed (EOP, 0.97). The possibility remained that the cI gene might exert an inhibitory effect if expressed constitutively from a high-copy-number vector. Therefore, the cI gene and adjacent operator region were amplified with PCR primers cI-XhoI-1 and cI-BamHI-2 (Table 1) and cloned into the high-copy-number, lactococcal shuttle vector pTRKH2 (36). This plasmid, pTRK676, originally obtained in E. coli, yielded only a few transformants in L. lactis NCK203 in repeated experiments. All the transformants contained plasmids with deleted inserts, except for one isolate where a full-length insert was recovered. Plasmid DNA from this NCK203 transformant was used to transform E. coli MC1061. Sequencing of the subcloned insert revealed a single base-pair point mutation within the cI gene (Fig. 1B). This mutation truncated the predicted CI protein by substituting a T for a C at bp 635. The plasmid encoding cI with the ochre mutation (pTRK677) was designated pTRKH2::CI-per1, where the “per1” is for phage-encoded resistance. Plasmid pTRK676 was also used to transform L. lactis MG1363 (Table 1), a prophage-cured related strain. Transformants were not obtained. Factors related to the apparent toxicity of the wild-type φ31 CI gene in L. lactis were not investigated.

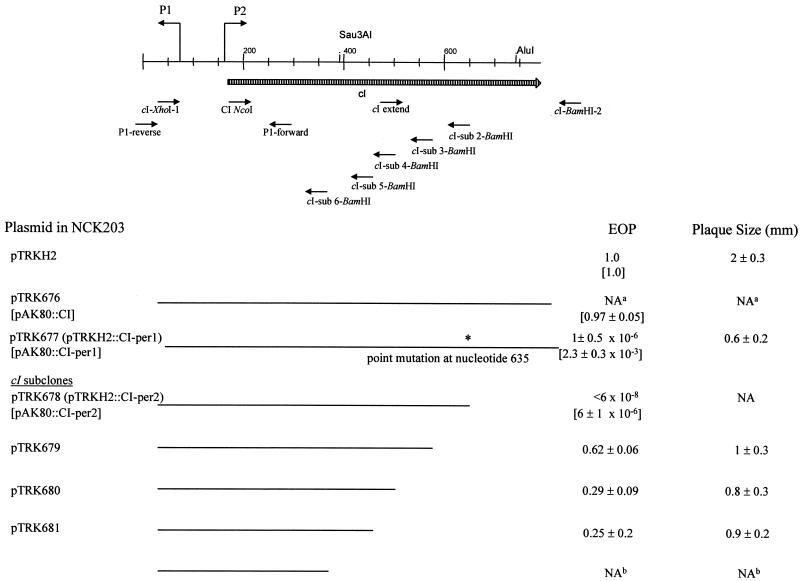

L. lactis NCK203 harboring pTRKH2::CI-per1 was challenged with phage φ31. The EOP was 10−6, with reduced plaque size (Fig. 2), indicating that the mutated cI gene was functional and conferred significant levels of resistance to phage φ31.

FIG. 2.

Schematic of the cI gene denoting subcloned fragments and their effect on phage φ31. Lines indicate regions subcloned into pTRKH2. EOPs and plaque sizes in millimeters are for phage φ31 plated on NCK203 containing the subclones. EOPs for the identical fragments cloned into pAK80 are given in brackets. The ∗ indicates the point mutation C to T that truncated the CI protein. a, full-length wild-type pTRHH2::cI NCK203 transformant was not obtained; b, the pTRKH2 subclone could not be obtained in E. coli.

Subcloning of the cI gene to determine the active region of the CI repressor.

The cI gene was subcloned in various lengths by insertion of XhoI/BamHI-digested PCR products into similarly digested pTRKH2 (Fig. 2). In each PCR, φ31 DNA was used as the template and cI-XhoI-1 was used as the left primer (the same left primer used for the construction of pTRK676). The right primers were designed to introduce stop codons, truncating CI at different locations (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The plasmids were transformed into E. coli MC1061 or TOP10-competent cells and confirmed by restriction site mapping and by sequencing of the inserts. Plasmids were electroporated into NCK203, and the transformants were again confirmed by analysis of restriction digests of the plasmid DNA. The EOPs of phage φ31 on L. lactis NCK203 derivatives containing the various-length subclones are shown in Fig. 2. Again, no NCK203 transformants were obtained using the full-length wild-type cI insert. NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per1), containing the point mutation shown in Fig. 1, limited φ31 to an EOP of 10−6 with reduced plaque size. Subclone pTRK678, henceforth designated pTRKH2::CI-per2, shortened the cI-coding region at the identical position where the ochre mutation of pCI-per1 created a stop codon. The EOP of φ31 was reduced on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per2) to below the level of detection (<6 × 10−8). Three smaller subclones of cI, pTRK679, pTRK680, and pTRK681, limited the EOP of φ31 to levels between 0.25 and 0.62, with varying reductions in plaque size. A smaller fragment of the cI gene was not recovered in pTRKH2 in E. coli.

To compare the effect of copy number, the CI-per1 and CI-per2 fragments were separately subcloned into the medium-copy-number vector pAK80 (19). As reported previously (28), the EOP for phage φ31 was 0.97 for pAK80::CI but, surprisingly, pAK80::CI-per1 and pAK80::CI-per2 lowered the EOPs of φ31 to 10−3 and 10−6, respectively (Fig. 2). In comparison with the EOPs for the same fragments cloned into pTRKH2, the weaker phenotype of CI-per in pAK80 correlated with the lowered gene dosage.

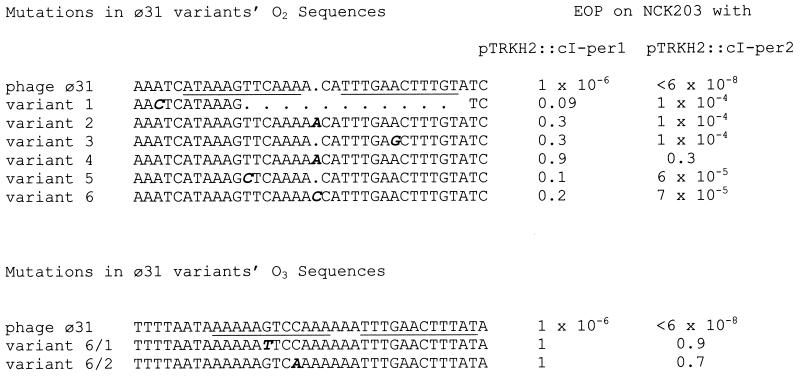

Analysis of phage φ31 mutants insensitive to CI.

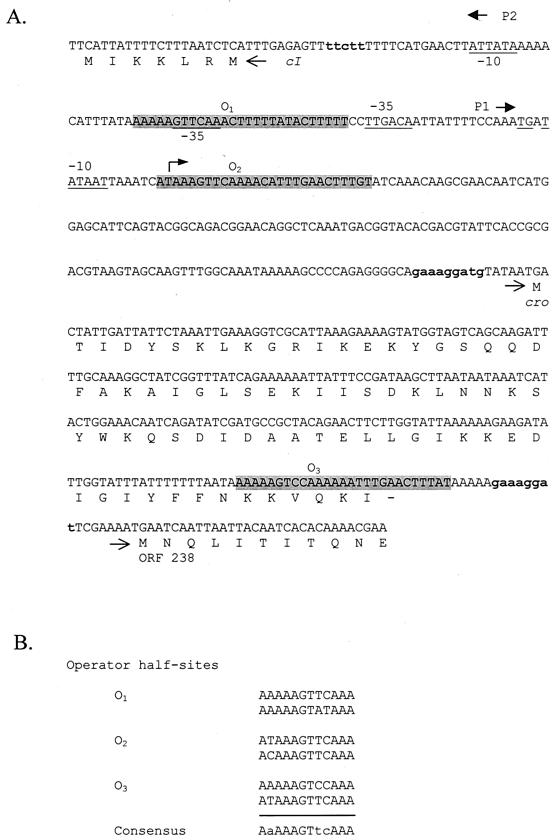

Six plaques were picked from lawns of phage φ31 on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per1), propagated on NCK203, and then replated on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per1). EOPs for the six phage variants ranged between 0.1 and 0.9 (compared to 10−6 for wild-type φ31), indicating that they were less susceptible to inhibition by CI-per1 (Fig. 3). When these variants were plated on NCK203 containing pTRKH2::CI-per2, EOPs of 10−4 to 10−5 occurred except for variant 4, which exhibited an EOP of 0.3. DNA was isolated from the mutant phages, the operator regions were amplified by PCR using primers P1-forward and P1-reverse (Table 1), and the products were sequenced on both strands from independently isolated PCR products. All six phages exhibited mutations in a 31-bp sequence which overlapped an imperfect inverted repeat, O2 (Fig. 3). Examination of the DNA sequence of φ31 (28) revealed two other occurrences of imperfect copies of the same inverted repeat (Fig. 4A). We hypothesize that the three imperfect repeats represent the putative operator regions of the genetic switch. Operator 1 (O1) overlaps the −35 site of promoter P2; O2 overlaps the transcriptional start site of promoter P1; and O3 occurs just upstream of the ribosome binding site of ORF 238 (Fig. 4A). The 12-bp operator half-sites are aligned in Fig. 4B, showing nine conserved bases. The half-sites are separated by three bases in each set of inverted repeats.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the mutated regions in the sequences of six cI-resistant φ31 variants showing the O2 operator and two representative double mutants showing the two mutations of the O3 operator. Mutated bases are in bold and italicized. The O2 and O3 operators are underlined in each φ31 sequence. EOPs are shown for each phage on NCK203 containing either pTRKH2::CI-per1 or pTRKH2::CI-per2.

FIG. 4.

(A) Sequence of φ31 DNA from the beginning of ORF cI through the beginning of ORF 238, showing the divergent promoters P1 and P2 and the putative operator sites of the regulatory region (O1, O2, and O3). The three putative operator sites are shaded. Arrows show the promoters P1 and P2, and the −10 and −35 sequences are underlined. A bent arrow indicates the transcriptional start site located downstream of P1. Potential ribosome binding sites are in bold lowercase letters. (B) Alignment of the half-sites of the three operator regions of phage φ31. Conserved bases in the consensus sequence are shown with capital letters.

The mutation in φ31 variant 1 deleted almost all of O2 (Fig. 3). The mutations in variants 3 and 5 each substituted a C for the same conserved T in the O2 half-site, but the substitutions occurred on different sides of the inverted repeat. Three of the φ31 mutants (variants 2, 4, and 6) had single base-pair insertions which increased the separation between the inverted repeats of O2 from three to four bases. Interestingly, variant 2 had an EOP of 0.3 on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per1), while variant 4 had an EOP of 0.9. In an attempt to identify any differences between variants 2 and 4, both were sequenced over the entire region containing the cI and cro genes, the operator region, and ORF238; however, no differences were found. An additional 20 pTRKH2::CI-per1-resistant phage isolates were screened, but none were resistant to the level of variant 4 (data not shown). Variant 4 most likely has a second mutation at a distal site that has an effect on CI binding or otherwise confers resistance to CI.

In an attempt to obtain double mutants, large plaques were isolated from lawns of variant 6 that plated on NCK203(pTRKH::CI-per2) at an EOP of 10−5 (Fig. 3). The phage isolates, when replated on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per2), exhibited EOPs of 0.7 to 0.9. Sequencing of six isolates revealed that a second mutation had occurred, this time in the O3 region of each phage (Fig. 3). Only two distinct mutations were found among the six isolates: a substitution of a T for a conserved G in variants 6/1, 6/3, and 6/5; and the substitution of an A for a nonconserved C in variants 6/2, 6/4, and 6/6 (Fig. 3). These data strongly indicate that both O2 and O3 are binding sites for the truncated φ31 CI repressor.

Binding of CI to the operator regions.

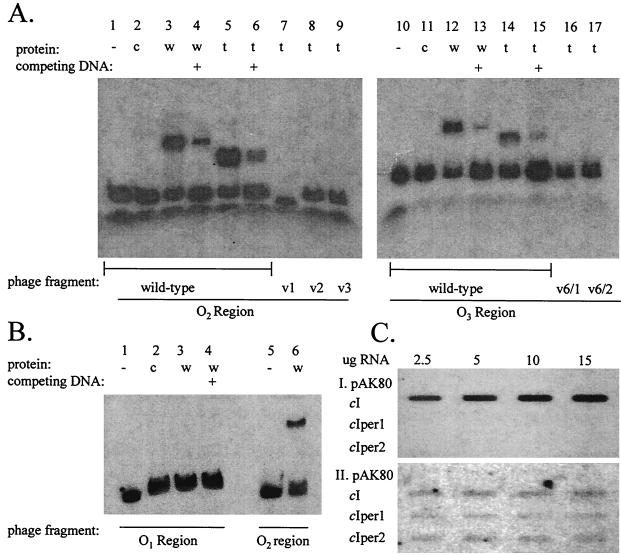

Gel mobility shift assays were performed to evaluate binding of CI to both the wild-type and mutated operator sites. Wild-type CI and truncated CI proteins were produced independently using the Single-Tube Protein System 3 from Novagen. The operator sites were PCR amplified from the wild-type φ31 and mutated phages using either the O1 left and right, the O2 left and right, or the O3 left and right primers shown in Table 1. The PCR products were labeled with 32P and the gel mobility shift assays were performed with CI and the truncated CI-per1 protein. The results are shown in Fig. 5. Both the wild-type and truncated CI proteins bound to the wild-type operators O2 and O3 (Fig. 5A). Binding of the truncated CI protein did not occur to the mutated operator sites of either the single-mutant phages (variants 1, 2, and 3) or double-mutant phages (variants 6/1 and 6/2), explaining their resistance to cI-per. In a separate experiment (Fig. 5B), the wild-type CI protein failed to bind operator O1 but continued to bind operator O2.

FIG. 5.

(A) Gel mobility shift assay showing binding to operators O2 and O3. Lanes 1 to 6, O2 fragment from wild-type phage φ31; lanes 7, 8, and 9, O2 fragments from the mutated φ31 variants (v) 1, 2, and 3, respectively; lanes 10 to 15, O3 fragment from wild-type phage φ31; lanes 16 and 17, O3 fragment from double-mutant φ31 variants (v) 6/1 and 6/2, respectively. Protein was produced in single-tube transcription-translation reactions using either the wild-type (w) φ31 cI gene (added to lanes 3, 4, 12, and 13) or the truncated (t) cI gene (added to lanes 5 to 9, and 14 to 17). Lanes 2 and 11 contain added control (c) transcription-translation reaction mixture lacking a cI template. Lanes 4, 6, 13, and 15 (indicated with a +) contain competing unlabeled O2 or O3 probe DNA. (B) Gel mobility shift assay showing wild-type CI binding. Lanes 1 to 4, O1 fragment from wild-type phage φ31; lanes 5 and 6, O2 fragment from the phage; wild-type CI protein was added in lanes 3, 4, and 6. Competing unlabeled O1 fragment DNA was added in lane 4 (indicated with a +). Lane 2 contains added control (c) transcription-translation reaction mixture lacking a cI template. (C) RNA slot blot probed with 32P-labeled PCR product from the P1 transcript (I) and from the start of the P2 transcript (II). Total RNA was isolated from NCK203 cells containing pAK80 and the indicated inserts in pAK80.

The ability of wild-type and truncated CI protein to repress RNA expression from promoters P1 (in the direction of Cro) and P2 (in the direction of CI) was analyzed by Northern hybridization. Various concentrations of total RNA isolated from log-phase NCK203 cells containing pAK80, pAK80::CI, pAK80::CI-per1, or pAK80::CI-per2 were probed with labeled PCR products from the 5′ region of the cI gene (obtained using primers cI sub4-BamHI and CI NcoI [Table 1]) and the start of the P1 transcript (using primers P1-reverse and O2 left). The results in Fig. 5C show that the presence of wild-type CI allows transcription from promoter P1, whereas the truncated CIs inhibit this transcription. There was no hybridization with RNA isolated from NCK203(pAK80). Initially, no P2 transcripts were detected for NCK203 cells containing any of the plasmids. Prolonged exposure revealed weakly hybridizing bands of comparable intensities for each of the CI- or CI-per-containing cells. Taken together, these results indicate that the dysfunctional wild-type CI binds operators O2 and O3 in vitro but does not repress transcription from the P1 promoter. In contrast, the truncated CI-per proteins are able to bind the operators and repress transcription. This information correlates with phenotypic data showing phage inhibition by truncated, but not wild-type, CI. Low-level transcription occurs from the P2 promoter in the presence of wild-type or truncated CI protein.

A putative ORF, shown in Fig. 1A as ORF 75, overlaps the 3′ end of the cI gene in an antisense configuration. The putative product has a region of about 20 amino acids which is identical to an internal region of ORF 50 from phage r1t (43). If expressed, this antisense transcript could theoretically interfere with CI expression. Total RNA isolated from NCK203(pTRKH2::cI-per1) was hybridized with a single-stranded DNA probe (end-labeled oligo 75 right [Table1]). No signal was detected (data not shown), indicating that ORF75 is not expressed and, therefore, should not affect expression of CI.

Effect of the phage φ31 cI gene expression on other lytic P335 phages.

P335 lytic phages known to propagate on NCK203 were tested for sensitivity to CI repression by plating on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per2). The results, shown in Table 2, indicate that only four of the phages, industrially isolated mm210a, mm210b, φ48 and φ50, were able to propagate freely in the presence of the truncated, highly expressed cI gene from phage φ31. In contrast, industrial isolates A1, B1, CS, and D1 and three closely related industrial isolates, Q30, Q33, and Q36, were unable to form plaques. L. lactis NCK203 has been shown to give rise to recombinant variants of phages φ31 and ul36 (12, 33). Phage φ31 and two of its variants, φ31.1 and φ31.2, as well as ul36 and its variant, ul37, were all unable to form plaques on NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per2).

TABLE 2.

Reduction in EOPs of P335 phages plated on L. lactis NCK203(pTRKH2::CI-per2)

| Phage | EOPa |

|---|---|

| φ31 | <2 × 10−8 |

| φ31.1 | <1 × 10−8 |

| φ31.2 | <2 × 10−8 |

| ul36 | <1 × 10−10 |

| ul37 | <2 × 10−8 |

| Q30 | <2 × 10−8 |

| Q33 | <1 × 10−8 |

| Q36 | <2 × 10−9 |

| mm210a | 0.9 |

| mm210b | 1 |

| A1 | <2 × 10−8 |

| B1 | <2 × 10−8 |

| CS | <9 × 10−9 |

| D1 | <5 × 10−9 |

| φ48 | 1 |

| φ50 | 2 |

Results are the average of three experiments.

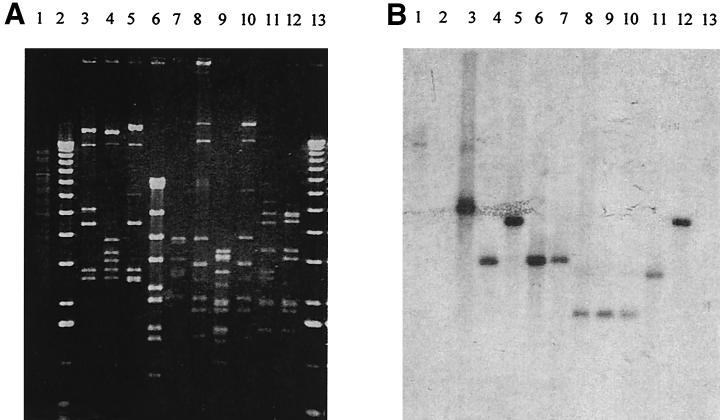

In situ gel hybridization was performed against genomic DNA from L. lactis NCK203 and 10 of the lytic P335 phages (eight were CI sensitive, two were CI resistant). Two 32P-labeled probes were PCR generated, one from φ31 DNA in the operator region (using primers P1-forward and P1-reverse [Table 1]) and the second from the C-terminal region of the cI gene (using primers cI-extend and cI-BamHI-2). The results are shown in Fig. 6. Even though each phage genome showed distinctive patterns after digestion with EcoRI, all 10 phages hybridized with both the operator region probe (Fig. 6) and the cI gene C-terminal probe (data not shown). The patterns of hybridization were identical for both the operator and CI probes, indicating the adjacent positions of the genetic switch and cI hybridizing fragments in all the phages examined. In addition, L. lactis NCK203 genomic DNA also hybridized to both probes, demonstrating the presence of homologous CI and operator sequences in the chromosome.

FIG. 6.

Hybridization of NCK203 and P335 phage DNAs with a probe from the putative operator region, upstream of cI. (A) Agarose gel of EcoRI-digested DNA. (B) Hybridization with a 32P-labeled probe amplified with the P1-forward and P1-reverse primers from φ31 DNA. Lanes: 1, genomic NCK203 DNA; 2 and 13, 1-kb ladder; 3 to 12, DNA from phages φ31, φ31.1, φ31.2, ul36, ul37, Q30, Q33, Q36, mm210a, and mm210b.

The genetic switch regions of two phages unaffected by CI-per (mm210a and mm210b) and two CI-per-sensitive phages (Q30 and ul36) were PCR amplified using primers P1-forward and P1-reverse (Table 1) and sequenced. All four contained the identical sequence as the wild-type, CI-sensitive φ31 over the region including promoters P1 and P2 and operators O1 and O2 (data not shown). These results provide no obvious explanation for the resistance of phages mm210a and mm210b to repression by φ31 CI-per.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that the CI repressor of phage φ31 is not functional and fails to retard superinfecting phages. In contrast, a truncated version of the CI repressor, when expressed constitutively at high copy in L. lactis, retards the proliferation of φ31 and other lytic P335 phages that are distinct phages but harbor a conserved genetic switch.

To our knowledge, φ31 is the first lytic Lactococcus bacteriophage to be characterized which encodes genes seemingly necessary for establishment of lysogeny (28), but it lacks the attachment site and integrase gene essential for a temperate life cycle. Temperate bacteriophages of lactic acid bacteria, which have lost their ability to lysogenize through spontaneous deletions within phage attachment sites and integrase genes, have been described in the literature (4, 5, 31). Therefore, it seems likely that φ31 also evolved from a temperate phage through deletion of DNA required for the establishment of lysogeny (28). Several other lytic P335 group phages used in this study, whether sensitive or resistant to CI repression, encoded identical genetic switch regions and may also have evolved from temperate phages. In this context, it is interesting to consider the loss of repressor function in the phage φ31 CI repressor. This outcome might be expected in an obligately lytic phage already deficient in an attachment site or integrase. More important, however, loss of repressor function may be advantageous to the recombinational lifestyle of phages in the P335 group, contributing to their evolution and adaptation (3).

Normally in a lambdoid temperate phage, the genetic switch region, along with regulatory proteins such as CI and Cro, controls whether the phage enters the lytic or temperate life cycle (15). Although lacking the integrase and attP site, phage φ31 otherwise has a lysogeny module with an overall genetic organization similar to that of temperate Siphoviridae from low-GC-content gram-positive bacteria (25, 28). However, in the case of φ31, CI evidently has no effect on the phage lytic cycle (28). Its promoter, P2, is weak and effectively repressed by Cro. The φ31 cI gene is closely related to the TP901-1 (28) repressor gene (Fig. 1), sharing a high level of homology over 117 bp. However, as would be expected for a true temperate phage, the TP901-1 CI repressor is a much more efficient repressor of both divergent promoters (27).

DNA homologies with gram-positive temperate phages are highlighted in Fig. 1. The first 114 bases are highly homologous with lactococcal phages BK5-T (5), phi LC3 (24), r1t (43), bIL309 (6), and Tuc2009 and occur in the genetic switch regions of these phages. However, this region of homology stops short of the promoter and operator region. Homologies to the repressor coding regions of bIL285 (6), TP901-1 (28), bIL286 (6), Tuc2009, and phi LC3 span from bp 487 to 603. Interestingly, although the homology with bIL286 continues, a two-codon gap occurs in the bIL286 sequence (bp 644 to 650) just after the point of the ochre mutation in pTRKH2::CI-per1 (bp 635), and the homology ends with the sequence TGAAAAAAGC. This 10-bp sequence may be a crossover point for DNA exchanges among phages, because it corresponds with the beginning of a short region of homology (from bp 747 to 793, corresponding with the C-terminal end of the cI ORF) shared with DNA from several phages: bIL286 (containing a repeat of the same 10 bp but from elsewhere in the bIL286 genome), bIL309, Tuc2009, BK5-T, r1t, and bIL312 (6). This 46-bp region lies outside of the genetic switch regions of the phages and results in an 11-residue divergence in the amino acid sequences of the otherwise homologous C-terminal ends of the repressors of φ31 and bIL286. Assuming that bIL286 has a normally functioning CI repressor, the differences between the sequences at their C-terminal ends could explain the loss of function of the wild-type φ31 CI.

In Fig. 1, amino acid homologies with related repressors from lactococcal phages TP901-1 (27), Tuc2009, r1t (43), BK5-T (4), and bIL286 (6), S. thermophilus phage phiO1205, and Staphylococcus aureus phage phi PVL are indicated. Two homologous regions among different phages are located in the N-terminal region. In general, the N terminal of CI homologues is involved in DNA binding, while the C terminal is involved in dimerization (15). Interestingly, the repressors of phages PVL, BK5-T, Tuc2009, and r1t are considerably larger than those of φ31, TP901-1, and phiO1205. Phages BK5-T, Tuc2009, and r1t are completely homologous over their C-terminal ends but not their N-terminal ends (34). It appears likely that the two domains of CI proteins, one involved in DNA binding and one in dimerization, have been subject to DNA interchanges among lactococcal temperate phages. The sequence identified as the r1t and Tuc2009 autodigestion site for self-cleavage is not found in either the φ31 or TP901-1 CI (26, 28). Searches of the Pfam (http://www.sanger.ac.uk) and PDB (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) databases of protein families based on structural similarity and X-ray crystal structures, respectively, placed the φ31 CI in the HTH_3 family of DNA-binding helix-turn-helix proteins, based on homologies with residues 3 to 66 of the N terminal (E value of 5 × 10−8 from The Sanger Centre). This family includes the Cro protein of bacteriophage 434 and the CI protein of lambda.

It is clear that the N-terminal region of the φ31 CI is important in phage inhibition. However, the smaller subclones of CI had significantly less effect on φ31 EOPs than pTRKH2::CI-per2 (Fig. 2). Only subclone pTRKH2::CI-per2 encompasses the entire region of DNA homology with phage TP901-1 (bp 487 to 603; Fig. 1) as well as two major regions of amino acid homology among related repressors shown in Fig. 1. Residues 3 to 66 are incorporated in the helix-turn-helix region of φ31 CI. These residues share similarities among phages φ31, TP901-1, phiO1205, and PVL. Logically, the sequence from residues 96 through 116, a region which shares homology among all the repressors, is likely to be necessary for repressor activity. This region of φ31 is included in pTRKH2::CI-per2 and appears to be necessary for the full antiphage activity of CI-per.

The wild-type CI binds operator sites O2 and O3 in vitro but is unable to repress the transcription of lytic genes. In contrast, the truncated version bound the operator sites in vitro and also effectively interfered with superinfecting phage replication. The difference in behavior between the full-length and truncated repressors is not understood at this time but could be due to differing affinities for the operator binding sites, to differences in the ability to bind cooperatively with other CI molecules, or to differing interactions with Cro, RNA polymerase, an antirepressor, or other host factors. The role of O1 is less clear, since wild-type CI does not bind O1 in gel retardation experiments, suggesting there is no self-repression of CI. Nevertheless, expression from the weak P2 promoter from a medium- or high-copy-number vector is sufficient for CI-per activity.

Interestingly, while the translated CI-per1 and CI-per2 proteins are predicted to be identical, deletion of the DNA downstream of the ochre mutation resulted in stronger inhibition of superinfecting phage (Fig. 2, compare the EOPs of pCI-per2 and pCI-per1). Copy numbers of pTRKH2::CI-per1 and pTRKH2::CI-per2 were identical when plasmid DNA preparations isolated from L. lactis cultures were compared in agarose gels visually and by densitometry (data not shown). Since the CI-per1 phenotypes (RNA expression and reduction in plaque formation of phage φ31) lay midrange between those of the wild-type CI (no effect) and CI-per2 (highly effective), we suspect that partial suppression of the ochre mutation in CI-per1 may result in some expression of the full-length, dysfunctional and ineffective wild-type CI. As a result, the effective truncated form of CI-per1 would be partially quenched, and self repression and superinfection immunity would be weakened.

CI-per1-resistant mutants of phage φ31 provided evidence that the truncated CI acts, in some capacity, at the operator region. All six single mutants had mutations within the same 31 bp containing a region of imperfect dyad symmetry. Three occurrences of the imperfect inverted repeats within the switch region were identified as putative operator sites. While the first two overlap the P2 promoter and P1 transcriptional start site, the third overlaps the 5′ end of the cro gene, just upstream of ORF 238. An analogous situation occurs in phage r1t, where operator sites O2 and O3 overlap the −35 sequences of the P1 and P2 promoters, but O1 is 402 bp further downstream, within the tec coding region (topological equivalent of the lambda cro gene [34]). The wild type, but not the mutated phage operators O2 and O3, were bound by truncated CI in gel mobility assays. Furthermore, P335 phages which encode identical operators may be either sensitive or resistant to the truncated CI, an indication that phage factors influence CI repression. This effect is also seen in the differing sensitivities of the φ31 operator mutants designated variants 2 and 4.

In both phage r1t and φ31, the genes downstream from cro encode putative antirepressors (28, 34). Some temperate phages have antirepressors which physically bind to and thus inactivate repressor proteins (41). To our knowledge, no experimental evidence has existed so far for the function of the putative antirepressors in lactococci. However, a significant role for the antirepressor cannot be ruled out. Primary mutations occurring in O2 lead to resistance to CI-per. CI repression at this point would presumably interfere with the expression of cro and all other genes downstream from the P1 early promoter, thus shutting down the phage lytic cycle. However, phages mutated in O2 were still partially sensitive to pCI-per2. Secondary mutations in O3 removed this sensitivity, either because CI binding at O3 prevents expression of the antirepressor, or simply further inhibits downstream expression from promoter P1. DNA looping could be involved through protein-protein contacts by repressors cooperatively binding the two operators (30, 40). In fact, the C1 repressor of bacteriophage P1 has been shown to mediate looping between operators (16). The fact that O3 is located immediately upstream from the start of ORF 238, rather than in the immediate region of the divergent promoters, also signifies the possible importance of the putative antirepressor.

The results presented here indicate that the wild-type phage φ31 CI repressor, while capable of binding operators O2 and O3, is dysfunctional, as CI neither inhibits infecting phage nor represses the P1 transcript encoding the phage lytic functions. Evolutionary events involving DNA exchanges with other P335 phages may have led to the loss of CI function. Regions of homology bracket the genetic switch region, which appears to be unique to φ31 and related P335 lytic phages. This phage group, therefore, may have evolved through deletion or inactivation of regions involved in lysogenic function.

Repressor genes from other lactic acid bacteria phages have been cloned and shown to limit proliferation of their cognate phages. An A2 repressor gene integrated into the chromosome of Lactobacillus casei rendered the strain completely resistant to phage A2 (2, 29). Background expression of the phage φadh repressor in Lactobacillus gasseri also conveyed complete resistance to phage φadh (13). In L. lactis, expression of the TP901-1 repressor conveyed complete immunity to the phage (27). Until now, the constitutive expression of CI has been of limited value as a phage resistance mechanism for lactic acid bacteria strains, since the immunity acts exclusively against the single phage from which the gene was cloned. Closely related phages were either not available or not evaluated. In contrast, this report demonstrates that the immunity provided by the truncated phage φ31 CI repressor is effective against 12 of 16 P335 group lytic phages tested.

There is high potential for genetic exchange among the P335 temperate and lytic phages as well as with prophage DNA residing in lactococcal genomes, due to extensive DNA homologies (3, 12, 33). The evolutionary possibilities resulting from loss of repressor function could be significant, since the genetic switch region appears to be highly conserved in the P335 group. An inactive CI repressor provides no barriers to superinfection or recombination and may, in this respect, support evolution of new related phages, via module exchange, in dairy environments. Conserved regions shared across all the P335 phages are limited, however (22). Thus, development and characterization of effective defenses, such as the truncated CI-per repressors which effectively target highly conserved regions in many of these phages, are of considerable practical significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Rhodia, Inc., Madison, Wis., by the USDA NRICGP under project 97-35503-4368, and by the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service (project NC06570).

We thank Michael Callanan, Olivia McAuliffe, Joseph Sturino, and Eric Altermann for helpful discussions and critical reviews of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alatossava, T., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1991. Molecular characterization of three small isometric-headed bacteriophages which vary in their sensitivity to the lactococcal phage resistance plasmid pTR2030. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1346-1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, M. A., A. Rodriguez, and J. E. Suarez. 1999. Stable expression of the Lactobacillus casei bacteriophage A2 repressor blocks phage propagation during milk fermentation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86:812-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchard, J. D., and S. Moineau. 2000. Homologous recombination between a lactococcal bacteriophage and the chromosome of its host strain. Virology 270:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce, J. D., B. E. Davidson, and A. J. Hillier. 1995. Spontaneous deletion mutants of the Lactococcus lactis temperate bacteriophage BK5-T and localization of the BK5-T AttP site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4105-4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruttin, A., and H. Brussow. 1996. Site-specific spontaneous deletions in three genome regions of a temperate Streptococcus thermophilus phage. Virology 219:96-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopin, A., A. Bolotin, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, and M.-C. Chopin. 2001. Analysis of six prophages in Lactococcus lactis IL1403: different genetic structure of temperate and virulent phage populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:644-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corpet, F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881-10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desiere, F., C. Mahanivong, A. J. Hillier, P. S. Chandry, B. E. Davidson, and H. Brussow. 2001. Comparative genomics of lactococcal phages: insight from the complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis phage BK5-T. Virology 283:240-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinsmore, P. K., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1997. Molecular characterization of a genomic region in a Lactococcus bacteriophage that is involved in its sensitivity to the phage defense mechanism AbiA. J. Bacteriol. 179:2949-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinsmore, P. K., D. J. O'Sullivan, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1998. A leucine repeat motif in AbiA is required for resistance of Lactococcus lactis to phages representing three species. Gene 212:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djordjevic, G. M., D. J. O'Sullivan, S. A. Walker, M. A. Conkling, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1997. A triggered-suicide system designed as a defense against bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 179:6741-6748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durmaz, E., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2000. Genetic analysis of chromosomal regions of Lactococcus lactis acquired by recombinant lytic phages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:895-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel, G., E. Altermann, J. R. Klein, and B. Henrich. 1998. Structure of a genome region of the Lactobacillus gasseri temperate phage phi adh covering a repressor gene and cognate promoters. Gene 210:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCD0712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriology 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gussin, G. N., A. D. Johnson, C. O. Pabo, and R. T. Sauer. 1983. Repressor and Cro protein: structure, function, and role in lysogenization, p. 93-121. In R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl, and R. A. Weisberg (ed.), Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Heinzel, T., R. Lurz, B. Dobrinski, M. Velleman, and H. Schuster. 1994. C1 repressor-mediated DNA looping is involved in C1 autoregulation of bacteriophage P1. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31885-31890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill, C., K. Pierce, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1989. The conjugative plasmid pTR2030 encodes two bacteriophage defense mechanisms in lactococci, restriction modification (R/M+) and abortive infection (Hsp+). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2416-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huynh, T. V., R. A. Young, and R. W. Davis. 1989. Construction and screening cDNA libraries in λgt10 and λgt11, p. 49-78. In D. M. Glover (ed.), DNA cloning, vol. 1. IRL Press, Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 19.Israelsen, H., S. M. Madsen, A. Vrang, E. B. Hansen, and E. Johansen. 1995. Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector, pAK80. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2540-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarvis, A. W. 1995. Relationships by DNA homology between lactococcal phages 7-9, P335 and New Zealand industrial lactococcal phages. Int. Dairy J. 5:355-366. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis, A. W., G. F. Fitzgerald, M. Mata, A. Mercenier, H. Neve, I. B. Powell, C. Ronda, M. Saxelin, and M. Teuber. 1991. Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology 32:2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labrie, S., and S. Moineau. 2000. Multiplex PCR for detection and identification of lactococcal bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:987-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Bourgeois, P., M. Lautier, M. Mata, and P. Ritzenthaler. 1992. New tools for the physical and genetic mapping of Lactococcus strains. Gene 111:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lillehaug, D., and N. K. Birkeland. 1993. Characterization of genetic elements required for site-specific integration of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage φLC3 and construction of integration-negative φLC3 mutants. J. Bacteriol. 175:1745-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucchini, S., F. Desiere, and H. Brussow. 1999. Similarly organized lysogeny modules in temperate Siphoviridae from low GC content gram-positive bacteria. Virology 263:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madsen, P. L., and K. Hammer. 1998. Temporal transcription of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901-1 and DNA sequence of the early promoter region. Microbiology 144:2203-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madsen, P. L., A. H. Johansen, K. Hammer, and L. Brondsted. 1999. The genetic switch regulating activity of early promoters of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J. Bacteriol. 181:7430-7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen, S. M., D. Mills, G. Djordjevic, H. Israelsen, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2001. Analysis of the genetic switch and replication region of a P335-type bacteriophage with an obligate lytic lifestyle on Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1128-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin, M. C., J. C. Alonso, J. E. Suarez, and M. A. Alvarez. 2000. Generation of food-grade recombinant lactic acid bacterium strains by site-specific recombination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2599-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews, K. S. 1992. DNA looping. Microbiol. Rev. 56:123-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikkonen, M., L. Dupont, T. Alatossava, and P. Ritzenthaler. 1996. Defective site-specific integration elements are present in the genome of virulent bacteriophage LL-H of Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1847-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moineau, S., M. Borkaev, B. J. Holler, S. A. Walker, J. K. Kondo, E. R. Vedamuthu, and P. A. Vandenbergh. 1996. Isolation and characterization of lactococcal bacteriophages from cultured buttermilk plants in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 79:2104-2111. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moineau, S., P. Sithian, T. R. Klaenhammer, and S. Pandian. 1994. Evolution of a lytic bacteriophage via DNA acquisition from the Lactococcus lactis chromosome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1832-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nauta, A., D. van Sinderen, H. Karsens, E. Smit, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1996. Inducible gene expression mediated by a repressor-operator system isolated from Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage r1t. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1331-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Sullivan, D. J., C. Hill, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. Effect of increasing the copy number of bacteriophage origins of replication, in trans, on incoming-phage proliferation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Sullivan, D. J., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. High- and low-copy-number Lactococcus shuttle cloning vectors with features for clone screening. Gene 137:227-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Sullivan, D. J., S. A. Walker, S. G. West, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1996. Development of an expression strategy using a lytic phage to trigger explosive plasmid amplification and gene expression. Bio/Technology 14:82-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 39.Sanders, M. E., P. J. Leonhard, W. D. Sing, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1986. Conjugal strategy for construction of fast acid-producing, bacteriophage-resistant lactic streptococci for use in dairy fermentations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:1001-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schleif, R. 1992. DNA looping. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:199-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shearwin, K. E., A. M. Brumby, and J. B. Egan. 1998. The Tum protein of coliphage 186 is an antirepressor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5708-5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terazghi, B. E., and W. E. Sandine. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl. Microbiol. 29:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Sinderen, D., H. Karsens, J. Kok, P. Terpstra, M. H. Ruiters, G. Venema, and A. Nauta. 1996. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1343-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker, S. A., C. S. Dombroski, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1998. Common elements regulating gene expression in temperate and lytic bacteriophages of Lactococcus species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker, S. A., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2000. An explosive antisense RNA strategy for inhibition of a lactococcal bacteriophage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:310-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker, S. A., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1998. Molecular characterization of a phage-inducible middle promoter and its transcriptional activator from the lactococcal bacteriophage φ31. J. Bacteriol. 180:921-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]