Abstract

The C30 carotene synthase CrtM from Staphylococcus aureus and the C40 carotene synthase CrtB from Erwinia uredovora were swapped into their respective foreign C40 and C30 biosynthetic pathways (heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli) and evaluated for function. Each displayed negligible ability to synthesize the natural carotenoid product of the other. After one round of mutagenesis and screening, we isolated 116 variants of CrtM able to synthesize C40 carotenoids. In contrast, we failed to find a single variant of CrtB with detectable C30 activity. Subsequent analysis revealed that the best CrtM mutants performed comparably to CrtB in an in vivo C40 pathway. These mutants showed significant variation in performance in their original C30 pathway, indicating the emergence of enzymes with broadened substrate specificity as well as those with shifted specificity. We discovered that Phe 26 alone determines the specificity of CrtM. The plasticity of CrtM with respect to its substrate and product range highlights the potential for creating further new carotenoid backbone structures.

A common feature of secondary metabolism is the extensive use of enzymes with broad substrate and product specificities. Many isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes, for example, accept a variety of both natural and unnatural substrates (37, 38, 41). Some have been shown to synthesize an impressively large number of compounds (sometimes >50) from a single substrate (12, 17, 55). Secondary metabolic pathways also use enzymes with remarkably stringent specificity. Such enzymes are frequently seen in key determinant positions, usually in the very early steps of a pathway, while promiscuous enzymes tend to be located further downstream. Thus, many secondary pathways have a “reverse tree” topology (3, 52), where the backbone structures of metabolites are dictated by a small number of stringent, upstream enzymes. When the substrate or product preferences of these key upstream enzymes are altered, pathway branches leading to sets of novel compounds may be opened (13). Our interest is to achieve the same by applying methods of directed enzyme evolution to recombinant pathways in Escherichia coli (53, 61).

Among the most widespread of all secondary metabolites, carotenoids are natural pigments that play important biological roles. Some are accessory light-harvesting components of photosynthetic systems, while others are photoprotecting antioxidants or regulators of membrane fluidity. Recent studies advocate their effectiveness in preventing cancer and heart disease (36), as well as their potential hormonal activity (5, 25). Such diverse molecular functions justify exploring rare or novel carotenoid structures. At present, ∼700 carotenoids from the naturally occurring C30 and C40 carotenoid biosynthetic pathways have been characterized (24). Most natural carotenoid diversity arises from differences in types and levels of desaturation and other modifications of the C40 backbone. C40 carotenoids are also much more widespread in nature than their C30 counterparts. The former are synthesized by thousands of plant and microbial species, whereas the latter are known only in a select few bacteria (56, 59). Homocarotenoids (carotenoids with >40 carbon atoms) and apocarotenoids (carotenoids with <40 carbon atoms), which result from the action of downstream enzymes on a C40 substrate, are also known. Although these structures do not have 40 carbon atoms, they are nonetheless derived from C40 carotenoid precursors (6).

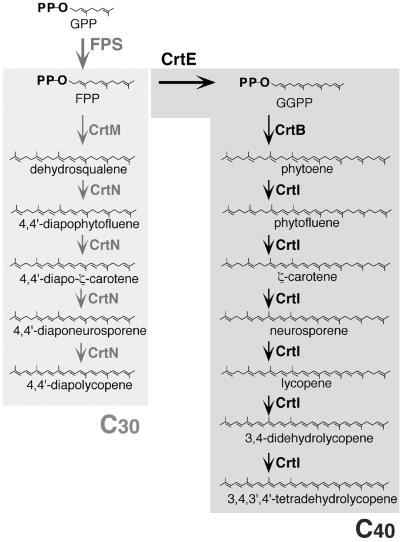

The first committed step in carotenoid biosynthesis is the head-to-head condensation of two prenylpyrophosphates catalyzed by a synthase enzyme (Fig. 1). The C40 carotenoid phytoene is synthesized by the condensation of two molecules of geranylgeranylpyrophosphate (GGPP) catalyzed by the synthase CrtB. C30 carotenoids are synthesized via an independent route whereby two molecules of farnesylpyrophosphate (FPP) are condensed to dehydrosqualene by CrtM (59). The various downstream modification enzymes possess broad substrate specificity and therefore represent potential targets for generating biosynthetic routes to novel carotenoids. For example, when the three-step phytoene desaturase CrtI from Rhodobacter sphaeroides was replaced with a four-step enzyme from Erwinia herbicola, the cells accumulated a series of carotenoids produced neither by Erwinia nor Rhodobacter (21). Carotene desaturases (49), carotene cyclases (54), and β-carotene cleavage enzyme (50) have also been shown to accept a broad range of substrates. Combinatorial expression of such enzymes can create unusual, sometimes previously unidentified, carotenoids (1, 2, 28). Nevertheless, the greatest potential to further extend carotenoid biosynthetic diversity lies in creating whole new backbone structures, and therefore with the carotene synthases.

FIG. 1.

Carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Carotenoid pathways are branches of the general isoprenoid pathway. In nature, two distinctive routes to carotenoid structures are known. C40 pathways, which start from the head-to-head condensation of two molecules of GGPP, are found in a variety of plant and microbial species. C30 pathways, which begin with the condensation of two molecules of FPP, have been identified only in a small number of bacterial species. The enzyme CrtE is a bacterial GGPP synthase; CrtM and CrtB are bacterial carotenoid synthases; CrtN and CrtI are bacterial carotenoid desaturases. PP, pyrophosphate; GPP, geranylpyrophosphate.

The C30 and C40 pathways are very similar except in the sizes of their precursor molecules and their distributions in nature, and it is clear that they diverged from a common ancestral pathway. We would like to determine the minimal genetic change required in key carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes to create such new pathway branches. Can the enzymes that synthesize one carotenoid be modified in a laboratory evolution experiment to synthesize others? How much of carotenoid diversity can be accessed in this way? And, can novel pathways to different, even unnatural, structures (e.g., C35, C45, C50, or larger carotenoids) be accessed by using C30 or C40 enzymes as a starting point? To begin to answer these questions, we studied the performance of the C30 carotene synthase CrtM from Staphylococcus aureus in a C40 pathway and the C40 carotene synthase CrtB from Erwinia uredovora in a C30 pathway. We then examined the ability of these enzymes to adapt to their respective “foreign” pathways in order to assess the ease and uncover the mechanisms by which this might be accomplished.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The C40 pathway genes crtE (GGPP synthase), crtB (phytoene synthase), and crtI (phytoene desaturase) from E. uredovora were obtained by genomic PCR as described previously (53). The E. coli farnesylpyrophosphate synthase (FPS) gene (fps) was cloned from E. coli strain JM109. The C30 pathway genes crtM (diapophytoene synthase) and crtN (diapophytoene desaturase) were cloned by PCR from S. aureus (ATCC 35556) genomic DNA. We used E. coli XL1-Blue supercompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) for cloning, screening, and carotenoid biosynthesis. AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.) was employed for mutagenic PCR, while Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was used for cloning PCR. All chemicals and reagents used were of the highest available grade.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid pUC18m was constructed by removing the entire lacZ fragment and multicloning site from pUC18 and inserting the multi-restriction site sequence 5′-CATATG-GAATTC-TCTAGA-CTCGAG-GGGCCC-GGCGCC-3′ (NdeI-EcoRI-XbaI-XhoI-ApaI-EheI). Each open reading frame following a Shine-Dalgarno ribosomal binding sequence (boldface) and a spacer (AGGAGGATTACAAA) was cloned into pUC18m to form artificial operons for acyclic C40 carotenoids (pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI) or acyclic C30 carotenoids (pUC-fps-crtM-crtN or pUC-crtM-crtN) (the genes in plasmids and operons are always listed in transcriptional order). To facilitate exchange between the two pathways, corresponding genes were flanked by the same restriction sites: prenyltransferase genes (fps and crtE) were flanked by EcoRI and XbaI sites, carotene synthase genes (crtM and crtB) were flanked by XbaI and XhoI sites, and carotene desaturase genes (crtN and crtI) were flanked by XhoI and ApaI sites (Fig. 2a).

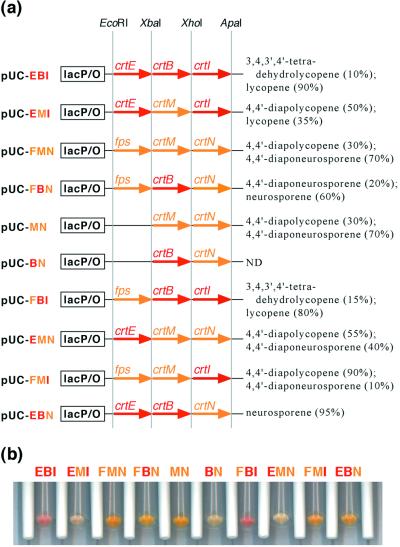

FIG. 2.

C30 and C40 production systems used in the paper. (a) Plasmids used in the work. Under the control of the lac promoter of a pUC18-derived plasmid, carotene synthase genes (crtB and crtM) were cloned into an XbaI-XhoI site, along with the prenyltransferase genes (crtE and fps; EcoRI-XbaI site) and the carotene desaturase genes (crtN and crtI; XhoI-ApaI site). Listed on the right are the approximate mole percentages (as a fraction of total carotenoids) of the main carotenoids produced by E. coli XL1-Blue cells transformed with each plasmid. Only major species consisting of at least 10% of total carotenoids are shown. (b) Cell pellets of XL1-Blue harboring various carotenogenic plasmids.

Error-prone PCR mutagenesis and screening.

A pair of primers (5′-GCTGCCGTCAGTTAATCTAGAAGGAGG-3′ and 5′-AGACGAATTGCCAGTGCCAGGCCACCG-3′) flanking crtM were designed to amplify the 0.85-kb gene by PCR under mutagenic conditions: 5 U of AmpliTaq (100 μl, total volume); 20 ng of template DNA (entire plasmid); 50 pmol of each primer; 0.2 mM dATP; 1.0 mM (each) dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP; and 5.5 mM MgCl2. Four different mutagenic libraries were made by using four different MnCl2 concentrations: 0.2, 0.1, 0.05, and 0.02 mM. The temperature cycling scheme was 95°C for 4 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 40°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 2 min and by a final stage of 72°C for 10 min. PCR yields for the 0.85-kb amplified fragment were 5 μg, corresponding to an amplification factor of ∼1,000 or ∼10 effective cycles. The PCR product from each library was purified with a Zymoclean gel purification kit (Zymo Research, Orange, Calif.), followed by digestion with XhoI and XbaI and DpnI treatment to digest the template. The PCR products were ligated into the carotene synthase gene site of vector pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI, resulting in pUC-crtE-[crtM]-crtI libraries (square brackets indicate the randomly mutagenized gene). PCR mutagenesis of crtB on plasmid pUC-crtB-crtN was performed with primers 5′-CTTTACACTTTATGCTTCCGG-3′ and 5′-TCCTGTGACACCTGCACCAATTACTGC-3′ under the same conditions used for mutagenesis of crtM. The PCR products were purified, digested, and ligated as described above into the carotene synthase gene site of pUC-crtB-crtN, resulting in four pUC-[crtB]-crtN libraries.

The ligation mixtures were transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue supercompetent cells. Colonies were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates containing carbenicillin (50 μg/ml) as a selective marker at 37°C for 12 h. Colonies were lifted onto white nitrocellulose membranes (Pall, Port Washington, N.Y.), transferred onto LB-carbenicillin plates, and visually screened for color variants after an additional 12 to 24 h at room temperature. Selected colonies were picked and cultured overnight in 96-well plates, each well containing 0.5 ml of liquid LB medium supplemented with carbenicillin (50 μg/ml).

Pigment analysis.

Among the strains we tested as expression hosts, XL1-Blue showed the best results in terms of stability and intensity of the color developed by colonies on agar plates. Although all of the genes assembled in each plasmid are grouped under a single lac operator/promoter, our expression system showed no response in terms of pigmentation levels to different IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) concentrations. Thus, leaky transcription from the lac promoter was sufficient for carotenoid production in E. coli. Based on this observation, all experiments described in this paper were performed without IPTG induction.

To measure the relative amounts of carotenoids synthesized (see Fig. 6), single colonies were inoculated into 3-ml precultures (LB medium containing 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml) and shaken at 250 rpm and 37°C overnight. Twenty microliters of each preculture was inoculated into 3 ml of Terrific broth (TB) medium (also containing 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml) and shaken for 24 (C30 carotenoid cultures) or 30 h (C40 carotenoid cultures) at 250 rpm and 30°C. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each culture was measured immediately before harvesting. Then, 2 ml of each TB culture was centrifuged, the liquid was decanted, and the resulting cell pellet was extracted with 1 ml of acetone. The absorbance spectrum of each extract was measured with a SpectraMax Plus 384 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Pigmentation levels in the culture extracts were determined from the height of absorption maxima (λmax): 470 nm for C30 and 475 nm for C40).

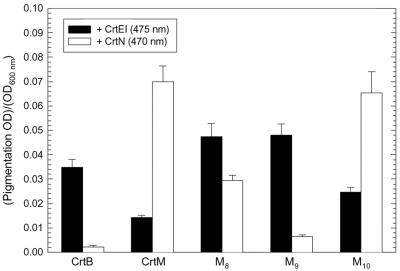

FIG. 6.

Pigmentation produced by CrtM variants in C40 and C30 pathways. XL1-Blue cells were transformed with either pUC-crtE-M8-10-crtI (C40 pathway) or pUC-M8-10-crtN (C30 pathway) and cultured in a test tube (3 ml of TB) as described in Materials and Methods. Pigmentation levels in the culture extracts were determined from the absorption peak height of λmax (470 nm for C30, 475 nm for C40) of each sample. Bar heights are normalized to OD600 and represent the averages of at least three replicates; error bars, standard deviations.

For accurate determination of the carotenoids produced by the cultures, 500 μl of LB preculture was inoculated into 50 ml of TB medium (containing 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml) and shaken in a 250-ml tissue culture flask (Becton Dickinson-Falcon, Bedford, Mass.) at 170 rpm and 30°C for 24 to 30 h. Cultures expressing only CrtE plus a carotenoid synthase (CrtB, CrtM, or a mutant CrtM) were cultivated in 50 ml of TB medium (containing 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml) for 40 h at 160 rpm and 28°C in 250-ml tissue culture flasks. The OD600 of each culture was measured immediately before harvesting, and the dry cell mass was determined from this measurement by using a calibration curve generated for similar cultures. After centrifugation, the cell pellets were extracted with 10 ml of an acetone-methanol mixture (2:1 [vol/vol]). Pigments were concentrated, and the solvent was replaced with 20 ml of hexane. Then, an equal volume of aqueous NaCl (100 g/liter) was added, and the mixture was shaken vigorously to remove oily lipids. The upper phase containing the carotenoids was dewatered with anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated in a rotary evaporator. The final volume of extract from each 50-ml culture was 1 ml. A 30- to 50-μl aliquot of extract was passed through a Spherisorb ODS2 column (250 by 4.6 mm; 5-μm pore size; Waters, Milford, Mass.) and eluted with an acetonitrile-isopropanol mixture (93:7 or 80:20 [vol/vol]) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min using an Alliance high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters) equipped with a photodiode array detector. Mass spectra were obtained with a series 1100 HPLC-mass spectrometer (Hewlett-Packard/Agilent, Palo Alto, Calif.) coupled with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization interface.

The molar quantities of carotenoids shown in Fig. 5 were determined by comparing HPLC chromatogram peak heights (at 286 nm) to that of a β-carotene standard (at 450 nm) and then multiplying by ɛbeta-carotene (450 nm)/ɛphytoene (286 nm). The values of the molar extinction coefficients (ɛ) used in the calculation were 138,900 and 49,800, respectively (7). The molar quantities of carotenoids were then normalized to the dry cell mass of each culture.

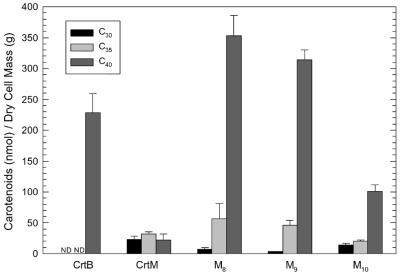

FIG. 5.

Direct product distribution of CrtM and its mutants in the presence of CrtE (GGPP supply). Carotenoid extracts of XL1-Blue cells carrying plasmids pUC-crtE-crtB, pUC-crtE-crtM, and pUC-crtE-M8-10 were analyzed by HPLC with a photodiode array detector. Peaks for 4,4′-diapophytoene (C30), 4-apophytoene (C35), and phytoene (C40) were monitored at 286 nm. Molar quantities of the various carotenoids were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Bar heights are normalized to dry cell mass and represent the averages of three replicates; error bars, standard deviations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Constructing pathways for C30 and C40 carotenoids.

To establish a recombinant C40 pathway in E. coli, we subcloned crtE encoding GGPP synthase, crtB encoding phytoene synthase, and crtI encoding phytoene desaturase, all from E. uredovora, into a vector derived from pUC18, resulting in plasmid pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI (Fig. 2a). For C30 carotenoid production, plasmid pUC-fps-crtM-crtN was constructed by integrating the E. coli FPS gene (fps) with crtM (dehydrosqualene synthase gene) and crtN (dehydrosqualene desaturase gene) from S. aureus into the same vector. Plasmid pUC-crtM-crtN was constructed in an identical fashion, but it lacks fps. Each plasmid shares the cloning sites for the corresponding enzyme genes: EcoRI and XbaI sites flank prenyltransferase genes (crtE and fps), XbaI and XhoI sites flank carotene synthase genes (crtB and crtM), and XhoI and ApaI sites flank carotene desaturase genes (crtI and crtN) (Fig. 2a). With this arrangement, corresponding genes could be easily swapped in order to evaluate their function in the other pathway.

E. coli cells harboring pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI plasmids (C40 pathway) developed a characteristic pink color, whereas cells possessing pUC-fps-crtM-crtN and pUC-crtM-crtN plasmids (C30 pathway) were yellow (Fig. 2b). HPLC analysis of extracted pigments showed that XL1-Blue(pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI) cells produce mostly lycopene (four-step desaturation) along with a small amount (5 to 10% of total pigment) of 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene (six-step desaturation) under the conditions described. Although CrtI is classified as a four-step desaturase, production of dehydrolycopene by CrtI both in vivo and in vitro has been reported (19, 32).

Several groups have expressed CrtM and CrtN from S. aureus in E. coli and observed almost exclusive production of 4,4′-diaponeurosporene (49, 62). However, in our XL1-Blue(pUC-crtM-crtN) expression system, the cells accumulated a significant amount of 4,4′-diapolycopene (∼30% of total carotenoids). When a constitutive lac promoter (lacking the operator) was used for operon expression, the amount of 4,4′-diapolycopene increased further and reached 50% of carotenoids produced (D. Umeno, unpublished data). This phenomenon was observed in all E. coli strains we tested, BL21, BL21(DE3), JM109, JM101, DH5α, HB101, SCS110, and XL10-Gold, and was insensitive to growth temperature and plasmid copy number. Thus, it is clear that the apparent desaturation step number of CrtN depends on its expression level and the effective concentration of substrates.

In E. coli, FPP is a precursor to a variety of important housekeeping molecules such as respiratory quinones, prenylated tRNA, and dolichol. Concerned about retarding or preventing the growth of our recombinant C30 cultures due to depletion of FPP, we first expressed the fps gene along with crtM and crtN. However, we observed no difference in growth rate, pigmentation level, or carotenoid composition between XL1-Blue cells harboring the pUC-crtM-crtN plasmid and those harboring the pUC-fps-crtM-crtN plasmid. This demonstrates that endogenous FPP levels in E. coli suffice to support both growth and synthesis of C30 carotenoids.

Functional analysis of CrtM and CrtB swapped into their respective foreign pathways.

To assess the function of wild-type CrtM in a C40 pathway, pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI was constructed and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. Under these circumstances, CrtM is supplied with GGPP produced by CrtE. If CrtM were able to synthesize the C40 carotenoid phytoene from GGPP, subsequent desaturation by CrtI to lycopene would cause the cells to develop a pink color. However, while cells expressing the crtE-crtB-crtI operon exhibited the characteristic pink of lycopene (Fig. 2b) and synthesized this carotenoid in liquid culture (see Fig. 4), cells expressing the crtE-crtM-crtI operon had only very subtle pink-orange color on agar plates and synthesized much less lycopene in liquid culture (see Fig. 4). As did Raisig and Sandmann (49), we thus conclude that CrtM fails to complement CrtB in a C40 pathway and has very poor ability compared to CrtB to synthesize the C40 carotenoid backbone. This observation cannot be explained by simple competition between FPP and GGPP for access to CrtM (coupled with poor ability of CrtI to desaturate the C30 product), because XL1-Blue cells expressing the crtE-crtM-crtN operon showed only very minor yellow color development. This indicates that the availability of FPP for carotenoid biosynthesis is significantly reduced upon expression of CrtE.

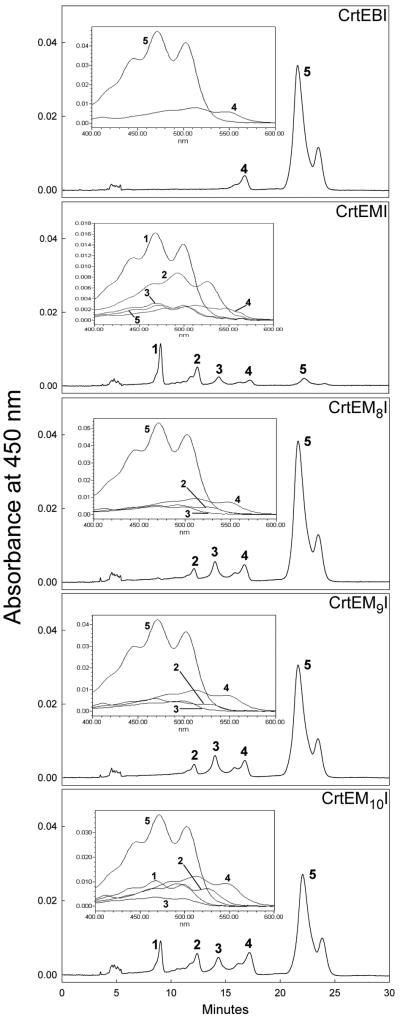

FIG. 4.

HPLC-photodiode array analysis of carotenoid extracts of E. coli transformants carrying plasmids pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI, pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI, and pUC-crtE-M8-10-crtI. The following carotenoids were identified: peak 1, 4,4′-diaponeurosporene (λmax [nm]: 467, 438, 414, M+ at m/e = 402.4); peak 2, 4-apo-3′4′-didehydrolycopene (λmax [nm]: 527, 490, 465, M+ at m/e = 466.4); peak 3, 4-apolycopene or 4-apo-3′4′-didehydro-7,8-dihydrolycopene (λmax [nm]: 500, 470, 441, M+ at m/e = 468.4); peak 4, 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene (λmax [nm]: 540, 510, 480, M+ at m/e = 532.4); peak 5, lycopene (λmax [nm]: 502, 470, 445, M+ at m/e = 536.5). Double peaks indicate different geometrical isomers of the same compound. Insets, recorded absorption spectra of individual HPLC peaks.

The function of CrtB in a C30 pathway was examined by analyzing the pigmentation of XL1-Blue cells transformed with pUC-crtB-crtN. In this case, endogenous FPP is the only available prenylpyrophosphate substrate for CrtB, since GGPP activity is not detected in E. coli. If CrtB could synthesize C30 carotenoids from FPP, the 4,4′-diapophytoene produced would be desaturated by CrtN and the cells would develop a yellow color. In contrast to the intense yellow of XL1-Blue transformed with pUC-crtM-crtN, XL1-Blue(pUC-crtB-crtN) showed no color development (Fig. 2b). When expressed alone or with CrtN, CrtB synthesized C30 carotenoids very poorly in liquid culture (see Fig. 5 and 6). We thus conclude that CrtB fails to complement CrtM in a C30 pathway.

We also analyzed the pigment produced by XL1-Blue carrying pUC-fps-crtB-crtN. In this case, the cells displayed a yellow color similar to that of XL1-Blue transformed with pUC-fps-crtM-crtN (Fig. 2b). HPLC analysis of carotenoid extracts from XL1-Blue(pUC-fps-crtB-crtN) revealed the C40 carotenoid neurosporene, with trace amounts of the C30 carotenoids 4,4′-diapolycopene and 4,4′-diaponeurosporene. Thus, CrtB seems to have at least some C30 activity in the presence of high levels of FPP. Production of the C40 carotenoid neurosporene as the major pigment is explained by the promiscuous nature of both FPS and CrtN. This was verified by our observation that cells expressing an fps-crtB-crtI operon had a weak pink hue and accumulated lycopene and 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene. Thus, FPS can produce significant amounts of GGPP in E. coli when overexpressed. It is known that avian FPS also possesses weak ability to synthesize GGPP (51). Indeed, other studies have shown a varied product distribution and strong dependence on conditions for FPS enzymes (35, 44). Additionally, CrtN can accept phytoene as a substrate and introduce two or three double bonds (49). When we transformed XL1-Blue with pUC-crtE-crtB-crtN, the resulting cells exhibited significant yellow color (Fig. 2b) and accumulated neurosporene, thus demonstrating the promiscuity of CrtN.

Screening for synthase function in a foreign pathway.

In the previous section, we confirmed that the carotene synthases CrtB and CrtM show negligible activity in their respective foreign pathways. We next proceeded to evolve the two enzymes, with the goal of improving the function of each in the other's native pathway. To uncover CrtB variants with significant CrtM-like ability to synthesize C30 carotenoids, we constructed pUC-[crtB]-crtN libraries and transformed them into XL1-Blue cells. Here GGPP is not available, so cells with the wild-type crtB-crtN operon fail to develop color. Any variants of CrtB able to convert FPP into 4,4′-diapophytoene would produce yellow colonies. Similarly, we searched for CrtM mutants with improved C40 activity by transforming four pUC-crtE-[crtM]-crtI libraries into XL1-Blue. As described in the previous section, the amount of FPP available for carotenoid biosynthesis becomes significantly depleted when CrtE is overexpressed, resulting in negligible production of C30 carotenoids, even by native C30 enzymes. Cells expressing wild-type CrtM from the crtE-crtM-crtI operon showed a weak pink-orange color due to trace production of C30 and C35 carotenoids, but CrtM mutants able to complement CrtB via enhanced C40 activity would be expected to yield intensely pink colonies and thus be distinguishable on the plates.

Evolution of dehydrosqualene synthase (CrtM) for function in a C40 pathway.

Four different mutagenic libraries of crtM corresponding to four different mutation rates were generated by performing error-prone PCR (65) on the entire 843-nucleotide crtM gene. PCR products from each reaction were ligated into the XbaI-XhoI site of pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI (Fig. 2), resulting in pUC-crtE-[crtM]-crtI libraries. Figure 3 shows a typical agar plate covered with a nitrocellulose membrane upon which lie colonies of E. coli XL1-Blue expressing a crtE-[crtM]-crtI library. In each library, colonies with pale orange, pale yellow, or virtually no color dominated the population. The pale orange colonies express variants of CrtM with phenotypes similar to that of the wild-type enzyme in this context, while the pale and colorless colonies express severely or completely inactivated synthase mutants. More rare were colonies that developed an intense red-pink color, indicating significant production of C40 carotenoids and hence improved CrtB-like activity of CrtM. On average, about 0.5% of the colonies screened showed intense red-pink color. The highest frequency of positives was obtained from the library prepared by PCR with the lowest MnCl2 concentration (0.02 mM). In this library, approximately 1 out of every 120 colonies was red-pink (0.8%). We screened over 23,000 CrtM mutants from the four libraries and picked 116 positive clones. These clones were rescreened by stamping them onto an agar plate covered with a white nitrocellulose membrane. All 116 stamped clones exhibited red-pink coloration. We sequenced the 10 most intensely red stamped clones, as determined by visual assessment. Mutations found in these variants (Table 1) were heavily biased toward transitions: 36 versus only 3 transversions. Additionally, 87% of the base substitutions found by sequencing were A/T→G/C. This is a typical observation for PCR mutagenesis with MnCl2 (10, 33). Out of 39 total nucleotide substitutions, 24 resulted in amino acid substitutions. Most notably, 9 of the 10 sequenced CrtM mutants had a mutation at phenylalanine 26.

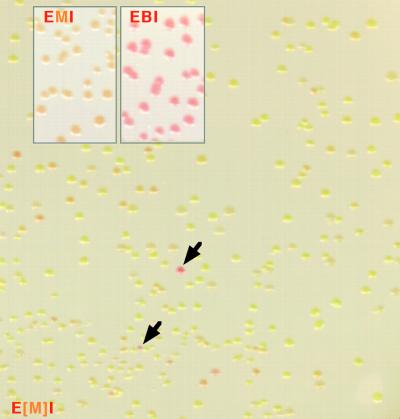

FIG. 3.

Typical plate with E. coli XL1-Blue colonies expressing a mutagenic library of CrtM together with CrtI and CrtE. XL1-Blue cells were transformed with pUC-crtE-[crtM]-crtI (E[M]I), where [crtM] represents a mutagenic library of crtM. Among a majority of pale colonies can be seen deep pink colonies (arrows) expressing CrtM variants that have acquired C40 pathway functionality. EMI and EBI, XL1-Blue cells transformed with pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI and pUC-crtE-crtB-crtI, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Mutations found in sequenced CrtM variants

| Mutant | Mutation(s)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Nonsynonymous (amino acid change) | Synonymous | |

| M1 | T76C (F26L), A364T (T122S) | A561G |

| M2 | A58G (K20E), T77C (F26S) | A471T |

| M3 | T76C (F26L), G127A (V43M) | A408G, T847C |

| M4 | T76C (F26L), A446G (E149G) | T150C, G489A, A726G, A850G |

| M5 | T76C (F26L), T800C (F267S) | |

| M6 | A35G (H12R), T76C (F26L), A80G (D27G), A290G (K97R), A620G (H207R) | A688G |

| M7 | T76C (F26L) | A186G, A447G |

| M8 | T78A (F26L) | A345G |

| M9 | T77C (F26S), T119C (I40T) | T135C, T141C |

| M10 | A10G (M4V), A35G (H12R), T176C (F59S), A242G (Q81R), A539G (E180G) | A39G |

Carotenoid production of evolved CrtM variants.

We analyzed in detail the in vivo carotenoid production of variant M8, which has the F26L mutation only, variant M9, which has the F26S mutation, and variant M10, which has no mutation at F26. To confirm the newly acquired CrtB-like function of these three sequenced variants of CrtM, XL1-Blue cultures carrying each of the three plasmids pUC-crtE-M8-crtI, pUC-crtE-M9-crtI, and pUC-crtE-M10-crtI (collectively referred to as pUC-crtE-M8-10-crtI) were cultivated in TB media. Extracted pigments were analyzed by HPLC with a photodiode array detector (Fig. 4). These analyses revealed that all three clones produced the C40 carotenoids lycopene (peak 5) and 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene (peak 4) as major products, whereas cells harboring the parent pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI plasmid produced mainly C30 and trace amounts of C40 and C35 carotenoids. Two carotenoids with C35 backbone structures were detected in extracts from cells harboring pUC-crtE-crtM-crtI and pUC-crtE-M8-10-crtI. Elution profiles, UV-visible spectra, and mass spectra confirm that one of the structures is the fully conjugated C35 carotenoid 4-apo-3′,4′-didehydrolycopene. We also detected C35 carotenoids with 11 conjugated double bonds. Because C35 carotenoids are asymmetric, there are two possible C35 structures that possess 11 conjugated double bonds: 4-apolycopene and 4-apo-3′,4′-didehydro-7,8-dihydrolycopene. At present, we have not determined whether the cells synthesize one (and if so, which one) or both of these C35 carotenoids.

Direct product distribution of CrtM variants in the presence of GGPP.

To directly evaluate the product specificities of the three CrtM mutants, we constructed pUC-crtE-M8-10 plasmids and transformed the plasmids into XL1-Blue cells. Here the CrtM variants are supplied with GGPP, but the carotenoid products cannot be desaturated. Because all three possible products in this scenario, 4,4′-diapophytoene (C30), 4-apophytoene (C35), and phytoene (C40), have an identical chromophore structure consisting of three conjugated double bonds, the molecular extinction coefficients for all three can be assumed to be equivalent, irrespective of the total number of carbon atoms in the carotenoid molecule (60). Thus, the product distribution of the CrtM variants can be discerned from the HPLC chromatogram peak heights (at 286 nm) for each product. As can be seen in Fig. 5, cultures expressing CrtB along with CrtE produced approximately 230 nmol of phytoene/g of dry cell mass but did not detectably synthesize C30 or C35 carotenoids. CrtE-CrtM cultures produced about 20 to 35 nmol of each of the C30, C35, and C40 carotenoids/g. In stark contrast, CrtE-M8 and CrtE-M9 cultures, which express synthases mutated at F26, generated over 300 nmol of phytoene/g. These cultures also produced 40 to 75% more C35 carotenoids but 70 to 90% fewer C30 carotenoids than CrtE-CrtM cultures. Cultures expressing M10, which has no mutation at F26, along with CrtE synthesized roughly 100 nmol of phytoene/g as well as about 20 and 14 nmol of C35 and C30 carotenoids/g, respectively.

Comparison of the C40 and C30 performance of CrtM variants.

To compare the acquired CrtB-like C40 function of the CrtM mutants with their CrtM-like ability to synthesize C30 carotenoids, the three mutants were placed back into the original C30 pathway, resulting in pUC-M8-10-crtN plasmids. Pigmentation analysis of cells carrying these as well as pUC-crtE-M8-10-crtI plasmids (Fig. 6) revealed that the CrtM variants retained C30 activity, although the C30 pathway performance of cells expressing these mutants varied. Acetone extracts of cultures expressing variant M8, which has the F26L mutation alone, along with CrtE and CrtI (CrtE-M8-CrtI cultures) had more than threefold-higher C40 carotenoid absorbance (475 nm) than extracts of CrtE-CrtM-CrtI cultures. However, the C30 carotenoid absorbance (470 nm) of extracts of cultures expressing variant M8 and CrtN was only about 40% that of CrtM-CrtN cultures. Cultures expressing variant M9, which has the F26S mutation, along with CrtE and CrtI also yielded extracts with over three times the C40 signal of CrtE-CrtM-CrtI culture extracts. Yet the C30 signal of M9-CrtN culture extracts was only about 10% that of CrtM-CrtN culture extracts. Cultures expressing mutant M10, which has no mutation at F26, along with CrtE and CrtI generated extracts with approximately 70% higher C40 absorbance than extracts of CrtE-CrtM-CrtI cultures. Interestingly, cultures expressing M10 and CrtN showed no reduction in C30 pathway performance compared to CrtM-CrtN cultures. M10 was the only 1 of the 10 sequenced variants that gave this result (data not shown).

Analysis of mutations.

The most significant and only recurring mutations found in the 10 sequenced CrtM variants were those at F26. In seven variants, phenylalanine is replaced by leucine, while two have serine at this position. The F26L substitution alone is sufficient for acquisition of C40 activity by CrtM (M8; Table 1). Thus, we conclude that mutation at residue 26 of CrtM directly alters the enzyme's specificity. Changing enzyme expression level or stability would not lead to increased C40 performance and decreased C30 performance of cultures expressing CrtM variants compared to those expressing wild-type CrtM (Fig. 6). Variant M10 possesses no mutation at amino acid position 26. Thus, it is apparent that mutation at this residue is not the only means by which CrtM can acquire CrtB-like activity. Of all 10 sequenced variants, M10 is the only one with no substitution for phenylalanine at position 26 and is also the only one whose cultures did not have decreased C30 pathway performance compared to CrtM cultures.

Structural considerations: mapping mutations onto human SqS.

Most structurally characterized isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes, including FPS, squalene synthase (SqS), and terpene cyclases, have the same “isoprenoid synthase fold,” consisting predominantly of α-helices (31). In addition, secondary structure prediction (14) and sequence alignment (11) of CrtM and CrtB with their related enzymes also suggest that the enzymes have a common fold. Given this and the lack of a crystal structure for a carotenoid synthase, we mapped the amino acid substitutions in our CrtM variants onto the crystal structure of human SqS (47).

SqSs catalyze the first committed step in cholesterol biosynthesis. As with carotene synthases, this is the head-to-head condensation of two identical prenylpyrophosphates (FPP for SqS). The condensation reaction catalyzed by SqS proceeds in two distinct steps (48). The first half-reaction generates the stable intermediate presqualene pyrophosphate, which forms upon abstraction of a pyrophosphate group from a prenyl donor, followed by 1-1′ condensation of the donor and acceptor molecules. In the second half-reaction, the intermediate undergoes a complex rearrangement followed by a second removal of pyrophosphate and a final carbocation-quenching process (Fig. 7). SqSs catalyze the additional reduction of the central double bond of dehydrosqualene by NADPH to form squalene, a reaction not performed by carotene synthases. Because the SqS and carotene synthase enzymes share clusters of conserved amino acids and catalyze essentially identical reactions, it is probable that they also have the same reaction mechanism. Indeed, when NADPH is in short supply, SqS produces dehydrosqualene, the natural product of CrtM (26, 63).

FIG. 7.

Reaction schemes for SqS and CrtM. PSPP, presqualene pyrophosphate.

Sequence alignment of CrtM with related enzymes implies that F26 in CrtM corresponds to I58 in human SqS, which is located in helix B and points into the pocket that accommodates the second half-reaction. This residue is located four amino acids downstream of a flexible “flap” region in SqS that is believed to form a “lid” that shields intermediates in the reaction pocket from water (47). The amino acids constituting the flap are almost completely conserved among all known head-to-head isoprenoid synthase enzymes that catalyze 1-1′ condensation.

It is noteworthy that a single mutation at F26 of CrtM is sufficient to permit this enzyme to synthesize C40 carotenoids. Because this position is thought to lie in the site of the second half-reaction (rearrangement and quenching of a cyclopropylcarbinyl intermediate) (47) and because wild-type CrtM produces trace amounts of phytoene (indicating that initially accepting two molecules of GGPP is not impossible), it is likely that wild-type CrtM is able to perform the first half-reaction of phytoene synthesis (condensation of two molecules of GGPP to form a presqualene pyrophosphate-like structure). We hypothesize that the F26 residue prevents the second half-reaction from going to completion by acting as a steric or electrostatic inhibitor of intermediate rearrangement. When this bulky phenylalanine residue is replaced with a smaller or more flexible amino acid such as serine or leucine, the second half-reaction is permitted to proceed and phytoene is produced.

Similar results for a variety of short-chain prenyltransferases have been reported. In this class of enzymes, the size of the fifth amino acid upstream of the first aspartate-rich motif determines product length (39, 42, 43, 45, 46). Based on a very strong correlation between average product length and surface area of amino acids in this position (46), as well as the available crystal structure for avian FPS (58), it was hypothesized that this residue forms a steric barrier or wall that controls the size of the products (40). This model has been successfully applied to a variety of other enzymes in this family, including medium-chain prenyltransferases (64). It is unknown why so many prenyltransferases differing so greatly in sequence share a single key residue that determines product specificity.

Evolution of phytoene synthase (CrtB) in a C30 pathway.

We constructed mutant libraries of crtB to search for variants with C30 activity. Four mutagenic PCR libraries differing in MnCl2 concentration were ligated into the XbaI-XhoI site of pUC-crtB-crtN, resulting in four pUC-[crtB]-crtN plasmid libraries. Upon transformation into XL1-Blue, pUC-crtB-crtN, containing wild-type crtB, gave no discernible pigmentation, while the pUC-crtM-crtN cells produced had intense yellow pigmentation. Among the ∼43,000 colonies expressing pUC-[crtB]-crtN variants screened, not a single one showed distinguishable yellow (or other) pigmentation. Thus, we found no CrtB mutants with improved C30 activity. We also constructed five additional pUC-[crtB]-crtN libraries by using the Genemorph PCR mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), which enables the construction of randomly mutagenized gene libraries with a mutational spectrum different from that of those generated by mutagenic PCR with MnCl2 (10). We screened an additional ∼10,000 variants but again found no variants of CrtB able to synthesize C30 carotenoids at appreciable levels.

An explanation for the relative difficulty in acquiring C30 function for CrtB may be that accepting a smaller-than-natural substrate is a more difficult task for this type of enzyme than accepting a larger-than-natural substrate. However, an evolutionary explanation may also be in order. The contexts in which the two enzymes evolved differ markedly. FPP is a precursor for many life-supporting compounds and is present in all organisms. Thus, C40 enzymes such as CrtB have evolved in the presence of FPP throughout their history. It is not unreasonable to infer that CrtB has evolved under a nontrivial selection pressure to minimize consumption of FPP, for accepting FPP as a substrate and bypassing GGPP could be detrimental to the host organism's fitness. In stark contrast, C30 synthases have evolved in an environment essentially devoid of GGPP. Consequently, no pressure to reject this substrate has been placed on these enzymes.

It has been suggested that secondary metabolic pathways possess inherent traits that enhance their ability to produce chemical diversity and thus maximize their likelihood of accessing biologically active molecules (18, 27). This hypothesis would be supported by a high degree of “evolvability” of the constituent enzymes. The substrate and product specificities of the isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes, specifically carotene synthases, are, in fact, easily modified. Product formation in this class of enzymes is determined primarily by the rearrangement and quenching of a highly reactive carbocation intermediate (31). Therefore, many products are possible from a single intermediate, and the main role of the synthase enzyme is to guide the rearrangement process. Because this process is very sensitive to small changes in the local chemical environment, many different amino acid substitutions would be expected to alter the product specificity of a carotenoid synthase. Thus, directed evolution of this class of enzymes appears to be a powerful tool for exploring a variety of different chemical structures in the laboratory.

In our experiments and with our expression system, carotene synthases CrtM and CrtB failed to function in their respective foreign pathways. However, upon random mutagenesis of crtM followed by C40-specific color complementation screening, we isolated 116 mutants of the enzyme (∼0.5% of the total screened) with significant C40 activity. The in vivo C40 pathway performance of the best CrtM variants is comparable to that of CrtB, the native C40 synthase. These results do not stand in isolation; such relative ease of altering specificity has been reported for other isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes (4, 8, 9, 15, 16, 20, 22, 23, 29, 30, 34, 42, 43, 45, 46, 53, 57).

We have shown for the first time that the substrate and product range of a carotene synthase can be easily altered in the laboratory by directed evolution. That the C30 carotenoid synthase CrtM, a key biosynthetic enzyme that determines the size of the carotenoids in the downstream pathway, is a mere single base substitution from becoming a C40 synthase is a finding of evolutionary and technological significance. How many more mutations need to accumulate before CrtM is completely transformed into a C40-only synthase? Can CrtM or CrtB be made to convert substrates other than FPP and GGPP? These and other questions should be answered by further laboratory evolution of carotenoid synthases.

Acknowledgments

D.U. acknowledges support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. A.V.T. acknowledges a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada PGS A scholarship. This research was supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation and Maxygen, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, M., S. Takaichi, N. Misawa, G. Schnurr, P. Boger, and G. Sandmann. 1997. Synthesis of atypical cyclic and acyclic hydroxy carotenoids in Escherichia coli transformants. J. Biotechnol. 58:177-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, M., S. Takaichi, S. Steiger, Z. Y. Wang, and G. Sandmann. 2000. Novel hydroxycarotenoids with improved antioxidative properties produced by gene combination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:843-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, G. A., and J. E. Hearst. 1996. Carotenoids 2: genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis. FASEB J. 10:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back, K. W., and J. Chappell. 1996. Identifying functional domains within terpene cyclases using a domain-swapping strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6841-6845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Dor, A., A. Nahum, M. Danilenko, Y. Giat, W. Stahl, H. D. Martin, T. Emmerich, N. Noy, J. Levy, and Y. Sharoni. 2001. Effects of acyclo-retinoic acid and lycopene on activation of the retinoic acid receptor and proliferation of mammary cancer cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 391:295-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton, G. 1998. Overview of carotenoid biosynthesis, p. 13-140. In G. Britton, S. Liaan-Jensen, and H. Pfander (ed.), Carotenoids, vol. 3. Birkhauser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland.

- 7.Britton, G. 1995. UV/visible spectroscopy, p. 13-62. In G. Britton, S. Liaan-Jensen, and H. Pfander (ed.), Carotenoids, vol. 1B. Birkhauser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland.

- 8.Cane, D. E., J. H. Shim, Q. Xue, B. C. Fitzsimons, and T. M. Hohn. 1995. Trichodiene synthase—identification of active-site residues by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 34:2480-2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cane, D. E., Q. Xue, and B. C. Fitzsimons. 1996. Trichodiene synthase. Probing the role of the highly conserved aspartate-rich region by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 35:12369-12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline, J., and H. Hogrefeo. 1999. Randomize gene sequences with new PCR mutagenesis kit. Stratagies 13:157-162. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpet, F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881-10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crock, J., M. Wildung, and R. Croteau. 1997. Isolation and bacterial expression of a sesquiterpene synthase cDNA clone from peppermint (Mentha x piperita, L.) that produces the aphid alarm pheromone (E)-beta-farnesene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12833-12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croteau, R., F. Karp, K. C. Wagschal, D. M. Satterwhite, D. C. Hyatt, and C. B. Skotland. 1991. Biochemical characterization of a spearmint mutant that resembles peppermint in monoterpene content. Plant Physiol. 96:744-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuff, J. A., M. E. Clamp, A. S. Siddiqui, M. Finlay, and G. J. Barton. 1998. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 14:892-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham, F. X., and E. Gantt. 2001. One ring or two? Determination of ring number in carotenoids by lycopene epsilon-cyclases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2905-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang, T. Y., and G. D. Prestwich. 2000. Site-directed mutagenesis of squalene-hopene cyclase: altered substrate specificity and product distribution. Chem. Biol. 7:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facchini, P. J., and J. Chappell. 1992. Gene family for an elicitor-induced sesquiterpene cyclase in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11088-11092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firn, R. D., and C. G. Jones. 2000. The evolution of secondary metabolism—a unifying model. Mol. Microbiol. 37:989-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser, P. D., N. Misawa, H. Linden, S. Yamano, K. Kobayashi, and G. Sandmann. 1992. Expression in Escherichia coli, purification, and reactivation of the recombinant Erwinia uredovora phytoene desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:19891-19895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujikura, K., Y. W. Zhang, H. Yoshizaki, T. Nishino, and T. Koyama. 2000. Significance of Asn-77 and Trp-78 in the catalytic function of undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase of Micrococcus luteus B-P 26. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 128:917-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Asua, G., H. P. Lang, C. N. Hunter, and R. J. Cogdell. 1998. Carotenoid diversity: a modular role for the phytoene desaturase step. Trends Plant Sci. 3:445-449. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart, E. A., L. Hua, L. B. Darr, W. K. Wilson, J. H. Pang, and S. P. T. Matsuda. 1999. Directed evolution to investigate steric control of enzymatic oxidosqualene cyclization. An isoleucine-to-valine mutation in cycloartenol synthase allows lanosterol and parkeol biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:9887-9888. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirooka, K., S. Ohnuma, A. Koike-Takeshita, T. Koyama, and T. Nishino. 2000. Mechanism of product chain length determination for heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:4520-4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hornero-Méndez, D., and G. Britton. 2002. Involvement of NADPH in the cyclization reaction of carotenoid biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 515:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishimi, Y., M. Ohmura, X. X. Wang, M. Yamaguchi, and S. Ikegami. 1999. Inhibition by carotenoids and retinoic acid of osteoclast-like cell formation induced by bone-resorbing agents in vitro. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 27:113-122. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarstfer, M. B., B. S. J. Blagg, D. H. Rogers, and C. D. Poulter. 1996. Biosynthesis of squalene. Evidence for a tertiary cyclopropylcarbinyl cationic intermediate in the rearrangement of presqualene diphosphate to squalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118:13089-13090. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones, C. G., and R. D. Firn. 1991. On the evolution of plant secondary chemical diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 333:273-280. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komori, M., R. Ghosh, S. Takaichi, Y. Hu, T. Mizoguchi, Y. Koyama, and M. Kuki. 1998. A null lesion in the rhodopin 3,4-desaturase of Rhodospirillum rubrum unmasks a cryptic branch of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway. Biochemistry 37:8987-8994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kushiro, T., M. Shibuya, and Y. Ebizuka. 1999. Chimeric triterpene synthase. A possible model for multifunctional triterpene synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:1208-1216. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kushiro, T., M. Shibuya, K. Masuda, and Y. Ebizuka. 2000. Mutational studies on triterpene syntheses: engineering lupeol synthase into beta-amyrin synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:6816-6824. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesburg, C. A., J. M. Caruthers, C. M. Paschall, and D. W. Christianson. 1998. Managing and manipulating carbocations in biology: terpenoid cyclase structure and mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8:695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linden, H., N. Misawa, D. Chamovitz, I. Pecker, J. Hirschberg, and G. Sandmann. 1991. Functional complementation in Escherichia coli of different phytoene desaturase genes and analysis of accumulated carotenes. Z. Naturforsch. 46C:1045-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LinGoerke, J. L., D. J. Robbins, and J. D. Burczak. 1997. PCR-based random mutagenesis using manganese and reduced dNTP concentration. BioTechniques 23:409-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathis, J. R., K. Back, C. Starks, J. Noel, C. D. Poulter, and J. Chappell. 1997. Pre-steady-state study of recombinant sesquiterpene cyclases. Biochemistry 36:8340-8348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuoka, S., H. Sagami, A. Kurisaki, and K. Ogura. 1991. Variable product specificity of microsomal dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 266:3464-3468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayne, S. T. 1996. Beta-carotene, carotenoids, and disease prevention in humans. FASEB J. 10:690-701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagaki, M., S. Sato, Y. Maki, T. Nishino, and T. Koyama. 2000. Artificial substrates for undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase from Micrococcus luteus B-P 26. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 9:33-38. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagaki, M., A. Takaya, Y. Maki, J. Ishibashi, Y. Kato, T. Nishino, and T. Koyama. 2000. One-pot syntheses of the sex pheromone homologs of a codling moth. Laspeyresia promonella L. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 10:517-522. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narita, K., S. Ohnuma, and T. Nishino. 1999. Protein design of geranyl diphosphate synthase. Structural features that define the product specificities of prenyltransferases. J. Biochem (Tokyo) 126:566-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogura, K., and T. Koyama. 1998. Enzymatic aspects of isoprenoid chain elongation. Chem. Rev. 98:1263-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohnuma, S., H. Hemmi, T. Koyama, K. Ogura, and T. Nishino. 1998. Recognition of allylic substrates in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase: analysis using mutated enzymes and artificial allylic substrates. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 123:1036-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohnuma, S., K. Hirooka, H. Hemmi, C. Ishida, C. Ohto, and T. Nishino. 1996. Conversion of product specificity of archaebacterial geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase. Identification of essential amino acid residues for chain length determination of prenyltransferase reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 271:18831-18837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohnuma, S., K. Hirooka, C. Ohto, and T. Nishino. 1997. Conversion from archaeal geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase to farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Two amino acids before the first aspartate-rich motif solely determine eukaryotic farnesyl diphosphate synthase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5192-5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohnuma, S., T. Koyama, and K. Ogura. 1993. Alternation of the product specificities of prenyltransferases by metal ions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 192:407-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohnuma, S., T. Nakazawa, H. Hemmi, A. M. Hallberg, T. Koyama, K. Ogura, and T. Nishino. 1996. Conversion from farnesyl diphosphate synthase to geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase by random chemical mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10087-10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohnuma, S., K. Narita, T. Nakazawa, C. Ishida, Y. Takeuchi, C. Ohto, and T. Nishino. 1996. A role of the amino acid residue located on the fifth position before the first aspartate-rich motif of farnesyl diphosphate synthase on determination of the final product. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30748-30754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandit, J., D. E. Danley, G. K. Schulte, S. Mazzalupo, T. A. Pauly, C. M. Hayward, E. S. Hamanaka, J. F. Thompson, and H. J. Harwood. 2000. Crystal structure of human squalene synthase. A key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30610-30617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poulter, C. D., T. L. Capson, M. D. Thompson, and R. S. Bard. 1989. Squalene synthetase—inhibition by ammonium analogs of carbocationic intermediates in the conversion of presqualene diphosphate to squalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111:3734-3739. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raisig, A., and G. Sandmann. 2001. Functional properties of diapophytoene and related desaturases of C30 and C40 carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1533:164-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redmond, T. M., S. Gentleman, T. Duncan, S. Yu, B. Wiggert, E. Gantt, and F. X. Cunningham. 2001. Identification, expression, and substrate specificity of a mammalian beta-carotene 15,15 ′-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6560-6565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reed, B. C., and H. C. Rilling. 1976. Substrate binding of avian liver prenyltransferase. Biochemistry 15:3739-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sacchettini, J. C., and C. D. Poulter. 1997. Creating isoprenoid diversity. Science 277:1788-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt-Dannert, C., D. Umeno, and F. H. Arnold. 2000. Molecular breeding of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:750-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schnurr, G., N. Misawa, and G. Sandmann. 1996. Expression, purification and properties of lycopene cyclase from Erwinia uredovora. Biochem. J. 315:869-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steele, C. L., J. Crock, J. Bohlmann, and R. Croteau. 1998. Sesquiterpene synthases from grand fir (Abies grandis). Comparison of constitutive and wound-induced activities, and cDNA isolation, characterization, and bacterial expression of delta-selinene synthase and gamma-humulene synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2078-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takaichi, S., K. Inoue, M. Akaike, M. Kobayashi, H. Ohoka, and M. T. Madigan. 1997. The major carotenoid in all known species of heliobacteria is the C30 carotenoid 4,4′-diaponeurosporene, not neurosporene. Arch. Microbiol. 168:277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarshis, L. C., P. J. Proteau, B. A. Kellogg, J. C. Sacchettini, and C. D. Poulter. 1996. Regulation of product chain length by isoprenyl diphosphate synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15018-15023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarshis, L. C., M. J. Yan, C. D. Poulter, and J. C. Sacchettini. 1994. Crystal structure of recombinant farnesyl diphosphate synthase at 2.6-angstrom resolution. Biochemistry 33:10871-10877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor, R. F. 1984. Bacterial triterpenoids. Microbiol. Rev. 48:181-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor, R. F., and B. H. Davies. 1974. Triterpenoid carotenoids of Streptococcus faecium UNH 564P. Biochem. J. 139:751-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, C. W., and J. C. Liao. 2001. Alteration of product specificity of Rhodobacter sphaeroides phytoene desaturase by directed evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 276:41161-41164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wieland, B., C. Feil, E. Gloria-Maercker, G. Thumm, M. Lechner, J.-M. Bravo, K. Poralla, and F. Götz. 1994. Genetic and biochemical analyses of the biosynthesis of the yellow carotenoid 4,4′-diaponeurosporene of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 176:7719-7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, D. L., and C. D. Poulter. 1995. Biosynthesis of non-head-to-tail isoprenoids—synthesis of 1′-1-structures and 1′-3-structures by recombinant yeast squalene synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117:1641-1642. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang, Y. W., X. Y. Li, and T. Koyama. 2000. Chain length determination of prenyltransferases: both heteromeric subunits of medium-chain (E)-prenyl diphosphate synthase are involved in the product chain length determination. Biochemistry 39:12717-12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao, H., J. C. Moore, A. A. Volkov, and F. H. Arnold. 1999. Methods for optimizing industrial enzymes by directed evolution, p. 597-604. In A. L. Demain, J. E. Davies, R. M. Atlas, G. Cohen, C. L. Hershberger, W.-S. Hu, D. H. Sherman, R. C. Willson, and J. H. D. Wu (ed.), Manual of industrial microbiology and bio/technology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington D.C.