Abstract

AcrAB-TolC is a constitutively expressed, tripartite efflux transporter complex that functions as the primary resistance mechanism to lipophilic drugs, dyes, detergents, and bile acids in Escherichia coli. TolC is an outer membrane channel, and AcrA is an elongated lipoprotein that is hypothesized to span the periplasm and coordinate efflux of such substrates by AcrB and TolC. AcrD is an efflux transporter of E. coli that provides resistance to aminoglycosides as well as to a limited range of amphiphilic agents, such as bile acids, novobiocin, and fusidic acid. AcrB and AcrD belong to the resistance nodulation division superfamily and share a similar topology, which includes a pair of large periplasmic loops containing more than 300 amino acid residues each. We used this knowledge to test several plasmid-encoded chimeric constructs of acrD and acrB for substrate specificity in a marR1 ΔacrB ΔacrD host. AcrD chimeras were constructed in which the large, periplasmic loops between transmembrane domains 1 and 2 and 7 and 8 were replaced with the corresponding loops of AcrB. Such constructs provided resistance to AcrB substrates at levels similar to native AcrB. Conversely, AcrB chimeras containing both loops of AcrD conferred resistance only to the typical substrates of AcrD. These results cannot be explained by simply assuming that AcrD, not hitherto known to interact with AcrA, acquired this ability by the introduction of the loop regions of AcrB, because (i) both AcrD and AcrA were found, in this study, to be required for the efflux of amphiphilic substrates, and (ii) chemical cross-linking in intact cells efficiently produced complexes between AcrD and AcrA. Since AcrD can already interact with AcrA, the alterations in substrate range accompanying the exchange of loop regions can only mean that substrate recognition (and presumably binding) is determined largely by the two periplasmic loops.

The multiple drug resistance (MDR) phenotype is often associated in bacteria with efflux pumps in the cytoplasmic membrane (13, 16). Collectively, these proteins belong to five families of transporters that include the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and the major facilitator superfamilies (MFS), as well as the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE), the resistance nodulation division (RND), and the small multidrug resistance (SMR) families (17, 22). A remarkable feature of some of these systems is the wide range of substrates that are recognized by a single pump protein.

The AcrAB system in Escherichia coli is the major MDR mechanism in E. coli (9, 11, 13, 16). The two genes of this system, acrA and acrB, encode a membrane fusion protein (MFP) and a cytoplasmic membrane efflux pump of the RND family, respectively. They confer resistance in E. coli to a variety of lipophilic and amphiphilic drugs, dyes, and detergent molecules that include tetracycline, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, erythromycin, fusidic acid, ethidium bromide, crystal violet, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and bile acids. Genetic studies showed that both genes were required for this resistance (10). Further mutational analysis suggested that this process also required an outer membrane channel, TolC, and therefore that the system probably functions as a tripartite complex (13, 16).

The pump proper, AcrB, is large in comparison to members of other transport families such as the MFS, sharing similar numbers of transmembrane domains (TMDs). Topological modeling of RND proteins reveals two large periplasmic loops of approximately 300 amino acids each between TMDs 1 and 2 and TMDs 7 and 8, and this accounts for their large sizes (21, 24). AcrB is thought to capture its substrates preferentially from within the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane (15). The drugs are extruded across the periplasmic space and the outer membrane via the combined action of AcrA and the TolC channel. This system is advantageous over simple cytoplasmic membrane pumps because it can extrude drugs directly into the extracellular medium (13, 14, 16).

The MFP component of this system, AcrA, has been shown to form homodimers, trimers, and also complexes with AcrB via chemical cross-linking (27). Although specific interactions between TolC and AcrAB have not been shown chemically, similar systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa are encoded as tripartite operons composed of genes coding for an MFP, efflux pump, and an outer membrane channel (reviewed in references 13 and 16).

Not all MDR efflux pumps export exclusively lipophilic and amphiphilic substrates. AcrD is responsible for resistance to a variety of aminoglycosides, a very hydrophilic class of drugs, and its gene does not form an operon with an MFP gene (20). However, a recent report has shown that AcrD can also mediate resistance to a limited range of amphiphilic compounds such as SDS, deoxycholate, and novobiocin (17). In this report, we utilize the differences in substrate specificities between AcrB and AcrD. We show with functional chimeras of the two proteins that the large periplasmic loops of these genes are principally responsible for drug specificity. Furthermore, we show that AcrD functions with AcrA, at least for some substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture techniques and strains.

All E. coli strains used in this study (Table 1) were maintained at −80°C in 15% (vol/vol) glycerol for cryoprotection. These strains were grown at 37°C, except when indicated otherwise (see “Construction of chromosomal deletion mutations,” below), in either Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl), 2× YT broth (1.6% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl), or on LB agar (1.5%) plates, made by using Difco components (Becton Dickinson).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmid constructs

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Relevant mutations | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| DH5α | Standard host strain for cloning | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) endA1 recA1 | Gibco BRL |

| AG102MB | Derived from AG100 (6, 18) | marR1 acrB::kan | S. Ohsuka and H. Nikaido, unpublished data |

| HNCE1a | Derived from AG102MB | marR1 acrB::kan ΔacrD | This study |

| HNCE1b | Derived from HNCE1a | marR1 acrB::kan ΔacrD acrA::cat | This study |

| Plasmids | |||

| pKD46 | λ Red recombinase (γ, β, exo) expression plasmid; amp, ara-inducible expression, temperature-sensitive replication | NAa | 3 |

| pKD3 | Template plasmid; amp, FRT-flanked cat | NA | 3 |

| pCP20 | FLP expression plasmid; amp, temperature-sensitive replication and FLP synthesis | NA | 3 |

| pSportIb | High-copy-number cloning and expression vector; amp, lac-inducible expression | NA | Gibco BRL |

| pAcrB | acrB clone from DH5α | V443I, I746Vc | This study |

| pAcrD | acrD clone from DH5α | D37G, Q63R, Q245R, M916I | This study |

| pAcrDup | acrD clone from DH5α with 304 nt of sequence 5′ of ATG start site | R252W, A687V | This study |

| pDbL12up | pAcrDup; L1 and L2 domainsd replaced with (→) respective domains of AcrB | F316L, E838G | This study |

| pDbL1 | pAcrD; L1 → AcrB L1 | M916I | This study |

| pDbL2 | pAcrD; L2 → AcrB L2 | D37G, Q63R, Q245R, S741P, M917I | This study |

| pDbL12 | Subcloned from pDbL12up; insert identical in size to coding capacity to AcrD-derived constructs | F316L, E838G | This study |

| pDbT1 | pAcrD; T1 → AcrB T1 | D37G, Q63R, Q245R, M917I | This study |

| pDbT2 | pAcrD; T2 → AcrB T2 | D37G, Q63R, Q245R | This study |

| pDbT12 | pAcrD; T1 and T2 → AcrB T1 and T2 | D37G, Q63R, Q245R, K324M | This study |

| pBdL1 | pAcrB; L1 → AcrD L1 | L21W, V443I, I746V | This study |

| pBdL2 | pAcrB; L2 → AcrD L2 | V443I | This study |

| pBdL12 | pAcrB; L1 and L2 → AcrD L1 and L2 | L21W, V443I | This study |

NA, not applicable, no mutation.

Plasmid vector used for all constructs created in this study.

Mutations in amino acid sequence of AcrD and AcrB domains in comparison with those reported in GenBank accession numbers P24177 and U00734, respectively.

See Fig. 1, and for precise boundaries see the description in Materials and Methods.

Oligonucleotide primers and miscellaneous chemicals.

Oligonucleotide primers used for cloning and mutagenesis techniques were obtained from Genemed Biotechnologies, Inc. (San Francisco, Calif.). Miscellaneous chemicals, including antimicrobial agents, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. unless indicated otherwise.

Construction of native acrD and acrB clones.

Restriction analysis of GenBank accession numbers P24177 (acrD) and U00734 (acrB) did not reveal any XbaI or BamHI sites within the open reading frames of these genes (approximately 3.2 kbp). Primers engineered with these restriction endonuclease sites were used to PCR amplify acrD and acrB from DH5α chromosomal DNA using a long and accurate Advantage cDNA polymerase mix (Clontech) under the conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The amplified DNA was purified and digested with both restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs) and ligated into similarly digested but dephosphorylated pSportI DNA (Gibco-BRL) (Table 1) under the control of the lac-inducible promoter. DH5α cells were electroporated with the ligated DNA and plated onto LB agar medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml for selection. Plasmid DNA from several transformants was digested with XbaI and BamHI, electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, and screened for inserts of approximately 3.2 kbp.

Construction of chromosomal deletion mutations.

E. coli mutants at the acrD and acrA loci (Table 1) were generated with a procedure based on the λ Red genes for recombination contained on pKD46 (3). AG102MB and HNCE1a cultures containing pKD46 were grown at 30°C, induced with 10 mM l-arabinose to express the Red genes, and made competent for electroporation. Linear DNA containing cat flanked by the FLP recognition target (FRT) sites was amplified by standard PCR from pKD3 using hybrid primers. These primers were homologous at the 3′ end to sequences in pKD3 but contained 50-nucleotide (nt) extensions at the 5′ end homologous to the intended sites of integration in E. coli. Transformants were selected on LB agar medium containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and screened for the expected integrations by PCR. In the case of HNCE1a, cat-mediated resistance was eliminated at the FRT sites with pCP20, which expresses the FLP recombinase. Since pKD46 and pCP20 are both temperature-sensitive replicons (Table 1), they were cured from E. coli strains by growth at 37 and 43°C, respectively (3).

Construction of chimeric transporter genes.

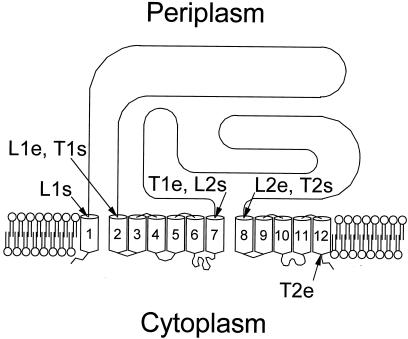

Transmembrane organization of AcrB and AcrD was predicted with hydropathy analysis using the TMpred program (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch:8080/software/TMPRED_form.html). These proteins appear to contain 12 TMDs and two large periplasmic loops between TMDs 1 and 2 and between TMDs 7 and 8 (Fig. 1). The proteins were divided into four domains: L1, amino acid residues 29 to 339 (AcrD and AcrB); L2, residues 557 to 870 (AcrD) or 558 to 872 (AcrB); T1, residues 340 to 556 (AcrD) or 340 to 557 (AcrB); T2, residues 871 to 1026 (AcrD) or 873 to 1029 (AcrB). Chimeras in which one or more of these domains were replaced precisely and in frame by those of the homologous gene were constructed by a novel PCR-based mutagenesis protocol (5) as follows (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Topological model of AcrD and AcrB efflux pumps, showing locations of chimeric fusions between these proteins. L1, loop 1 domain; T1, TMD 1; L2, loop 2 domain; T2, TMS 2. For all domains, start (s) and end (e) points are shown; for their precise locations in AcrD and AcrB, see Materials and Methods.

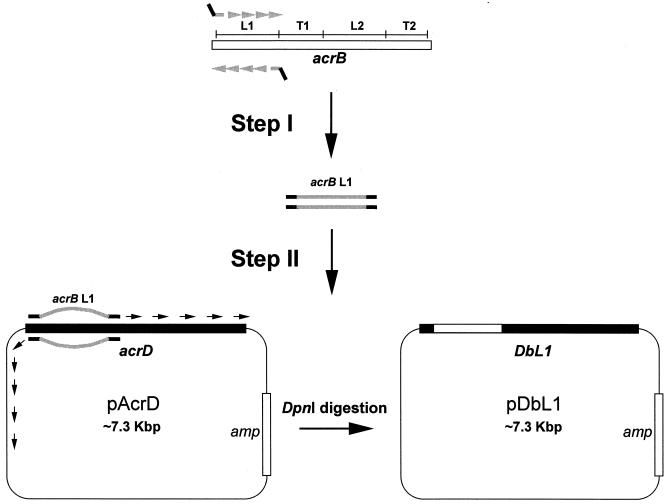

FIG. 2.

Ligation-independent PCR mutagenesis of acrD. In step I, we show an example of the PCR amplification of the DNA coding for L1 (see Fig. 1) from acrB (in gray), with a pair of hybrid primers containing in-frame homology extensions (approximately 25 nt) as well as the 5′ extensions (also about 25 nt) complementary to the intended start and end sites in acrD (in thick black lines). In step II, this amplicon was used as the primer in a second PCR to produce, in this case, the entire pDbL1 plasmid sequence containing the chimeric gene DbL1. The final DNA product was treated with DpnI to enrich for chimeric plasmids while simultaneously eliminating template plasmids encoding native acrD.

In the first step, DNA encoding the above-indicated individual domains in acrB, for example, was PCR amplified by using long primers that also contained acrD sequences (Fig. 2). Thus, the 3′-terminal halves (usually 25 to 28 nt) of pairs of hybrid primers were designed to complement the precise ends of each of the domains of acrB, but the 5′ portions (again, 25 to 28 nt) of such primers were designed in frame to complement the exact start and end sites of the corresponding domain of acrD. (Sequences of these primers are available from the authors upon request.) In the second step, the PCR amplicons were then used as primers in a second PCR with the Clontech Advantage cDNA polymerase mix and a plasmid containing the wild-type allele of acrD (pAcrD or pAcrDup) as template, so that the entire plasmid became amplified with the precise replacement of the desired domain (Fig. 2). (Replacement of acrB domains with acrD followed a similar procedure with appropriate changes in the templates.) Digesting with DpnI, which recognizes methylated DNA, eliminated template DNA encoding native pump proteins in the final PCR product (5). Newly synthesized plasmids encoding chimeric proteins were transformed into DH5α cells and screened with PCR for the expected domain replacements.

All cloned native and chimeric genes were sequenced completely (see below). The DNA sequence of pAcrD revealed a total of four amino acid substitutions (conservative and nonconservative) when compared to the sequence in GenBank accession number P24177 (Table 1). This apparently resulted from error in PCR amplification, because a second independent clone, pAcrDup, amplified from the genomic DNA of the same strain, DH5α, produced a protein with two amino acid substitutions, neither of which was present in AcrD encoded on pAcrD. Two amino acid substitutions were also observed in the protein product of acrB in pAcrB. However, all these “native” clones of acrB and acrD were fully functional (see Results).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Plasmid constructs created in this study (Table 1) were sequenced unidirectionally by using an automated method. Standard T7 Forward and SP6 primers and synthesized walking primers for DNA sequencing were used (Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., Hayward, Calif.).

Drug susceptibilities.

E. coli cells harboring pSportI-derived plasmids were tested for drug susceptibilities by two different methods. The MICs of several compounds (see Table 2) were measured using the microdilution technique in 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon; Becton Dickinson). Serial twofold dilutions of drugs were prepared in 150 μl of LB broth containing 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Gibco-BRL). The dilutions were inoculated with 10−2 volumes of cultures grown to mid-log phase in 1 ml of 2× YT broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. Visible signs of bacterial growth were observed at 24 h and verified at 48 h of growth at 37°C. Drug susceptibilities of these same cultures were measured in a second method using solid media (see Tables 2 and 3). Linear concentration gradients of drugs were prepared in square LB agar plates (2) containing 0.1 mM (final concentration) IPTG. Mid-log-phase cultures were grown as above and streaked as a linear, thick inoculum across the plate, parallel with the drug gradient. Bacterial growth across the plates from low to high drug concentrations was recorded in millimeters after 24 h at 37°C.

TABLE 2.

Drug susceptibility of E. coli HNCE1a expressing AcrB, AcrD, or chimeras under the lac-inducible promoter in pSportI

| Construct present | Relative MICa

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic acid | Taurocholic acid | Novobiocin | Fusidic acid | Ethidium bromideb | Crystal violetb | Ciprofloxacin | Chloramphenicol | Erythromycin | Tetracyclinec | |

| pSportI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | (1) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pAcrB | 8d | 32 | 64 | >64 | (13) | (>7) | 32 | 4 | >64 | 16 |

| pAcrD | 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | (1) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pDbL1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| pDbL2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pDbL12 | 8 | 32 | 64 | 64 | (13) | (>7) | 8 | 2 | 64 | 4 |

| pDbT1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| pDbT2 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pDbT12 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 4 | (2) | (1) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pBdL1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pBdL2 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 16 | (2) | (1) | 4 | 2 | 32 | 2 |

| pBdL12 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 4 | (2) | (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Relative MIC is the MIC for the relevant strain divided by the MIC for the control strain containing vector pSport1. The absolute values of MICs for the latter strains were as follows: cholic acid, 3,125; taurocholic acid, 6,250; novobioein 8; fusidic acid, 8; ciprofloxacin, 0.01; chloramphenicol, 2; erythromycin, 64; and tetracycline, 1 μg/ml. Differences in MIC values were confirmed in all cases by assays using gradient plates (see Materials and Methods) (data not shown).

For these colored agents, MICs were difficult to read in liquid media, and we therefore used drug gradient plates containing either 50 μg of ethidium bromide/ml or 12 μg of crystal violet/ml in the lower layer. Growth across the gradient was recorded in millimeters, with 80 mm being the maximum length of the plate. Values are shown in parentheses.

In the case of tetracycline, pAcrD and pAcrDup provided limited resistance on gradient plates but not in MIC determinations.

Values in boldface represent significant changes from the MIC for the host containing pSportI.

TABLE 3.

Gradient plate analysis of E. coli HNCE1a (acrA+) and HNCE1b (ΔacrA) cells expressing AcrB, AcrD, or AcrBD chimeras in pSportI

| Construct present | Length of growth zone (mm)a with drugb in strain a or bc

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic acid

|

Taurocholic acid

|

Novobiocin

|

Fusidic acid

|

Crystal violet

|

Ciprofloxacin

|

|||||||

| a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | |

| pSportI | 17 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 27 | 26 | 8 | 80d | 13 | 26 | 13 | 15 |

| pAcrB | 80 | 18 | 80 | 22 | 80 | 35 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 24 | 80 | 18 |

| pAcrD | 47 | 16 | 80 | 17 | 80 | 25 | 50 | 80 | 13 | 25 | 13 | 15 |

| pDbL12 | 65 | 21 | 80 | 20 | 80 | 37 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 26 | 80 | 12 |

| pDbT12 | 43 | 16 | 80 | 15 | 73 | 23 | 32 | 80 | 13 | 24 | 12 | 10 |

| pBdL12 | 35 | 18 | 68 | 15 | 44 | 26 | 30 | 80 | 13 | 25 | 10 | 9 |

The length of the plate was 80 mm. Thus, the value of 80 means complete resistance up to the highest concentration in the plate, and that the MIC may be any value higher than that.

The lower layer of the gradient plates contained (per ml) 8,000 μg of cholic acid, 6,500 μg of taurocholic acid, 25 μg of novobiocin, 35 μg of fusidic acid, 12 μg of crystal violet, or 0.01 μg of ciprofloxacin.

Strains harboring pSportI-derived constructs. a, HNCE1a; b, HNCE1b (see Table 1).

Values shown in boldface represent cases in which HNCE1b showed higher or lower susceptibility than HNCE1a.

Cross-linking in intact cells and Western hybridizations.

Chemical cross-linking of proteins in IPTG-induced (0.1 mM) E. coli cells harboring pSportI-derived constructs (Table 1) was performed with dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP; Pierce) at 0.5 mM (27). DSP-treated cells were harvested by centrifugation and sonicated in a 10−1 original volume of 1 mM EDTA-1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride-10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer. The crude envelope fraction of these cultures was collected by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and was solubilized at room temperature in 10−2 volumes of the same buffer containing 1% SDS. Protein complexes were resolved in SDS-7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer containing 20 mM Tris base-150 mM glycine-20% (vol/vol) methanol. Complexes containing AcrA and/or AcrB were probed with anti-AcrA and/or anti-AcrB polyclonal rabbit sera (25-27) and then with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.). These complexes were visualized with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (4).

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of native and chimeric constructs.

The acrD and acrB genes cloned in pAcrD, pAcrDup, or pAcrB were functional when expressed in HNCE1a and produced resistance levels similar to those previously reported. Thus, our data in Table 2) show that the novobiocin MIC increased fourfold with pAcrD (eightfold with pAcrDup [data not shown]), whereas Nishino and Yamaguchi reported a fourfold increase with an AcrD-expressing multicopy plasmid (17). Similarly, our pAcrB increased the MICs of chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and tetracycline by a factor of 4, >64, and 16, respectively, whereas the Nishino-Yamaguchi multicopy AcrB plasmid caused increases of 8-, 32-, and 8-fold. Because of these observations, these plasmids were used as templates to produce chimeric constructs, described below. The amplified acrB and acrD genes, however, contained a few mutations, apparently introduced by the PCR process (Table 1). Apparently these amino acid substitutions did not affect the drug efflux functions detectably.

Substrate recognition of constructs containing native AcrD and AcrB.

AcrD provides resistance to the aminoglycosides amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, kanamycin, and neomycin (20). We found that AcrD encoded in pAcrDup but not pAcrD increased the MICs of amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin in LB medium twofold, from 16 μg/ml for all drugs in HNCE1a/pSportI to 32 μg/ml. The lack of activity of pAcrD may be due to the stronger overproduction of AcrD from this plasmid (see Fig. 4, below), which may hinder the proper efflux of aminoglycosides. (In contrast, the MICs of all three aminoglycosides showed a small decrease to 8 μg/ml upon the introduction of pAcrB.) This minor increase in the MICs is typical for AcrD-mediated resistance to aminoglycosides. Rosenberg et al. (20) reported that MICs of aminoglycosides increased only two- to fourfold over control levels. Nishino and Yamaguchi (17) demonstrated that AcrD-mediated resistance from a high-copy-number plasmid increased the kanamycin MIC only twofold. Therefore, our levels of AcrD-mediated resistance agree with previously published results. Importantly, replacement of both AcrD loop domains of pAcrDup with the corresponding domains from AcrB (pDbL12up) abolished the increase in resistance to all three aminoglycosides tested and produced an eightfold decrease in the MICs of all aminoglycosides to 4 μg/ml.

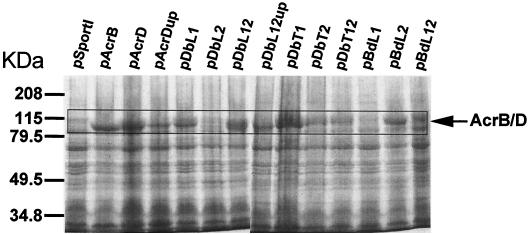

FIG. 4.

Expression analysis of native and chimeric transporters in HNCE1a cells induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Crude membrane extracts of un-cross-linked cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Total membrane proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel) and stained with Coomassie blue.

Although the disruption of acrD does not cause hypersusceptibility to lipophilic and amphiphilic drugs (8, 22), possibly due to its low constitutive level of expression, overexpression of AcrD from a high-copy-number plasmid in an acrAB-deficient host increases resistance to SDS, deoxycholate, and novobiocin (17). We found, similarly, that expression of AcrD from a high-copy-number vector, pSportI, increased the MICs of bile acids, novobiocin, and fusidic acid to a modest degree (maximally eightfold, if taurocholate was excluded) (Table 2, pAcrD data) in an acrB-acrD-deficient strain, E. coli HNCE1a. Gradient plate analysis also confirmed this finding (results not shown). In contrast, AcrB expression from the same vector not only created higher degrees of resistance to these agents but also increased the MICs of dyes (ethidium bromide and crystal violet), ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and tetracycline (Table 2, pAcrB data). The latter agents are not pumped out by AcrD, as judged on the basis of the MICs and gradient plate analysis. Thus, AcrB has a much wider range of substrates than AcrD, a result that confirms previously published results (8, 12, 17).

Strains containing pAcrD or pAcrDup (data not shown) showed small differences in MICs of aminoglycosides (see above) and lipophilic agents (data not shown). For example, MICs of bile and fusidic acids and of novobiocin were two- to fourfold higher for cells harboring pAcrDup than for cells containing pAcrD. Since pAcrDup contains additional DNA upstream of acrD (see Materials and Methods), this may affect the expression levels of the pump, as indeed shown below in Fig. 4. However, pDbL12 and pDbL12up are identical chimeras except for this additional DNA in pDbL12up, even though they produced similar levels of resistance (data not shown for pDbL12up). Thus, another cause(s), most probably the amino acid alterations introduced during PCR (see above), might contribute to this difference. Subsequent to our analysis with chimeric proteins (see below), we were able to obtain a mutation-free pAcrD construct with PCR using PfuTurbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). This construct produced MICs of lipophilic agents tested in this study that were in between the MICs measured for pAcrD and pAcrDup. These small differences did not affect the interpretation of the data.

Substrate recognition of constructs containing chimeras.

As was shown first with AcrB (8), the N-terminal half of RND transporters shows a strong sequence similarity to the C-terminal half, and this is reflected in the folding topology (Fig. 1). Furthermore, a BLAST analysis of AcrD and AcrB indicated that the two proteins are 63% identical and 76% similar in amino acid sequence. Many of the divergent sequences are found in the large L1 and L2 domains that occur at similar positions in the N-terminal and C-terminal halves (Fig. 1). In contrast, there are fewer differences in the TMDs of the two proteins.

We examined the substrate range of chimeras in which large loops, or TMDs (except TMD1), have been replaced by sequences from the other member of the AcrB/AcrD pair by determining MICs of various drugs (Table 2). In the first analysis, portions of acrB sequences were introduced into plasmids containing the acrD gene (see plasmids with names beginning with “pD”). When both the L1 and L2 loops of AcrB replaced the corresponding loops of AcrD (Table 2, pDbL12 data), the MICs of AcrB-specific drugs such as ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and tetracycline showed strong increases, indicating that these loops can determine, largely, the substrate specificity of the pump. The converse chimera in which these two loops of AcrB were replaced by the corresponding sequences of AcrD (Table 2, pBdL12 data) lost the ability to confer resistance to these AcrB-specific drugs, and the MIC pattern of the strain containing this chimera was largely similar to that of the strain containing nonchimeric AcrD. Finally, when both TMDs 2 to 7 (T1 domain [Fig. 1]) and TMDs 8 to 12 (T2 domain [Fig. 1]) of AcrD were replaced with the corresponding regions of AcrB (Table 2, pDbT12 data), the characteristic AcrD-like pattern of resistance was virtually unaltered. These results suggest that the two large periplasmic loops essentially determine the substrate specificity of the AcrD and AcrB transporters.

When individual domains from the N-terminal and C-terminal halves were independently replaced, the results were more complex. Independent replacement of the L1 or L2 domain of AcrD with the corresponding sequence from AcrB (pDbL1 and pDbL2, respectively) produced no increase in the MIC of any agent and thus resulted in the loss of the original AcrD-type resistance (Table 2). Since the chimeric protein DbL1 was produced from plasmid pDbL1 and found in crude membrane extracts (see below), we can assume that this chimeric protein is essentially inactive. Possibly L1 and L2 interact tightly in these proteins, and having the two domains from different origins inhibits this interaction. Chimeric protein DbL2 appears to be unstable (see below), and the transport properties of this protein remain unknown. Surprisingly, however, the AcrB-based chimera containing only the L2 region of AcrD (pBdL2) largely retained the AcrB-like substrate range (Table 2), in spite of the fact that this chimera contains the same combination of loops as pDbL1, which was inactive. These data might be explained if the large loops interact with TMDs or small loops that connect individual TMDs. In any case, the results with pBdL2 suggest that perhaps L1 plays a more important role in substrate recognition than does L2.

It should be noted that the transporters contained in pDbT12 were identical in sequence to that encoded by pBdL12 except for the N terminus, including TMD 1 and the short sequence directly C-terminal to TMD 12. Such residues may slightly affect the overall activity of the pump protein. pDbT12 and pBdL12 nevertheless produced very similar, AcrD-like resistance patterns (Table 2).

Effect of AcrA.

The results in Table 2 suggested that the narrow substrate range of the AcrD pump could be broadened to an AcrB-like range by the introduction of two large loop domains from AcrB. However, this does not immediately implicate the loops in substrate recognition. Because AcrD has been reported to function without AcrA (20), the introduction of the loop regions from AcrB could have simply resulted in a productive interaction of the chimeric transport protein with AcrA, and this could have caused the efflux of various lipophilic and amphiphilic substrates without directly altering the substrate recognition by the transporter.

We therefore examined the effect of various plasmids on resistance, using both acrA+ (HNCE1a) and ΔacrA (HNCE1b) host strains (Table 1). The study, performed by using gradient plates (Table3), unexpectedly showed that efflux of the characteristic, amphiphilic substrates (such as bile acids and novobiocin) by AcrD was completely dependent on AcrA. This was true for drug efflux catalyzed by AcrB as well as by various chimeras. Therefore, AcrD presumably interacts with AcrA, and the broader substrate range of chimeric transporters, such as DbL12, cannot be explained by the simple ability of the chimeric proteins to interact with AcrA (see also below).

Interestingly, the resistance to fusidic acid increased in the acrA mutant regardless of the nature of the transporter produced. Such an observation was not made in a previous study where fusidic acid resistance was measured in a ΔacrAB or ΔacrABD host (22). Our host strain HNCE1b (but not HNCE1a), however, contained a cat cassette in the disrupted acrA gene (Table 1). Previous studies with fusidic acid in E. coli have demonstrated that common variants of cat can mediate resistance to fusidic acid by sequestering the drug before it can bind elongation factor G and inhibit protein translation (1, 19). Thus, the fusidic acid resistance level in this strain was apparently determined by this specific mechanism and does not reflect the levels of drug efflux.

Expression of chimeric transporters and their interaction with AcrA analyzed by cross-linking.

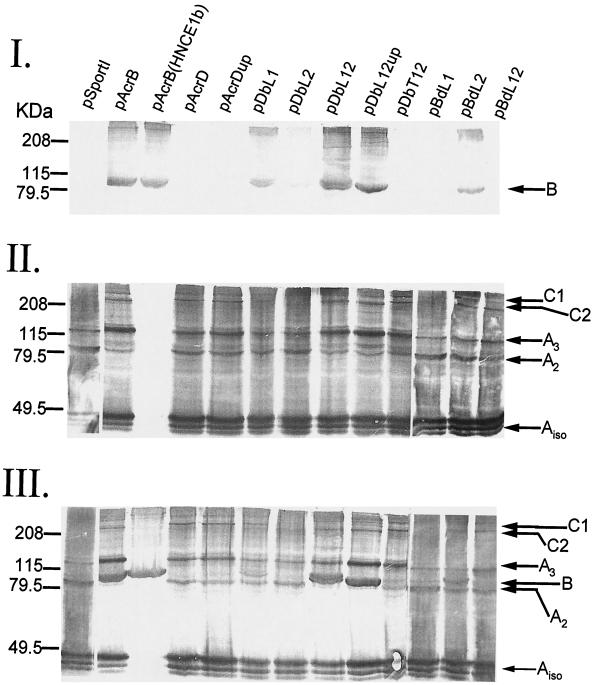

That AcrD function is dependent on AcrA for the efflux of novobiocin and bile acids was unexpected. We, therefore, used a previously reported cross-linking approach using DSP-treated cells (27) to determine whether AcrD physically interacts with AcrA (Fig. 3). This analysis also allowed us to examine the level at which the chimeric transporters were expressed.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of DSP-treated E. coli HNCE1a cells (HNCE1b cells were used for one of the pAcrB lanes) expressing AcrD, AcrB, or chimeric constructs (see Table 1). Cross-linked proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel) and probed with anti-AcrB (I), anti-AcrA (II), or both (III) antibodies. AcrA- and AcrB-specific complexes are indicated by arrows and explained in the text. kDa, molecular mass standards (broad range; Bio-Rad), in kilodaltons.

The membrane fractions from various strains were examined by immunoblotting with anti-AcrB and/or anti-AcrA antibodies. Anti-AcrB antibody recognized a protein band of approximately 100 kDa (Fig. 3, panel I, band B), the expected size of AcrB, in extracts from cells expressing AcrB but not AcrD or AcrD chimeras containing both loops of AcrD (pDbT12 and pBdL12) (Fig. 3, panel I) or control HNCE1a cells containing the vector alone (pSportI). Furthermore, chimeras expressing AcrB L1 (pDbL1 and pBdL2) or both loops of AcrB (pDbL12 and pDbL12up) were recognized by the antibody, but chimeras expressing only L2 from AcrB (pDbL2 and pBdL1) produced virtually no signal. These data show that at least the chimeric transporters encoded by pDbL12, pDbL12up, pDbL1, and pBdL2 are strongly expressed. AcrD expression could not be examined in this analysis, presumably because of the high specificity of the antibody, but its expression could be shown indirectly by cross-linked complexes of AcrD-AcrA (see below) and directly by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of un-cross-linked, crude membrane extracts (Fig. 4). Anti-AcrB antibody failed to detect DbL2 and BdL1, presumably because the antibody does not recognize the L2 domain. However, DbL2-AcrA and BdL1-AcrA cross-linked complexes were absent (see below), a result suggesting instability of these chimeras. Indeed, the bands of these chimeras were not visible on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4).

AcrB antibody often showed in addition a high-molecular-weight complex of >208 kDa (Fig. 3, panel I). This could correspond to an oligomer of AcrB, as it was seen also in the absence of AcrA [Fig. 3, panel I, pAcrB (HNCE1b)]. However, we cannot at present exclude the possibility of cross-linking of an AcrB monomer to another high-molecular-weight protein.

Probing with anti-AcrA revealed several complexes (Fig. 3, panel II). Three monomer AcrA products (Aiso) were observed in all cross-linked cells except HNCE1b (Fig. 3, panel II). The two faster-moving bands are the intramolecular cross-linking products of AcrA (H. Zgurskaya, personal communication). Two other major complexes with apparent molecular masses of 100 and 132 kDa were also observed, as previously reported (27). These complexes (A2 and A3) were previously identified as cross-linked dimers and trimers of AcrA. Finally, two high-molecular-weight complexes (>208 kDa) were also observed in all membrane preparations except for HNCE1a/pSportI, HNCE1a/pDbL2, HNCE1a/pBdL1, and HNCE1b/pAcrB cells. These complexes are similar in mobility to that of C2 and C1 previously reported (27) and represent cross-linked products containing both AcrA and the transporter (AcrB, AcrD, or chimeric protein). These complexes were present even in cells containing pAcrD (or pAcrDup) as well as pDbL12, pDbL12up, pDbL1, pBdL2, and pBdL12, a result suggesting that these chimeric proteins were present in a stable form in the membranes of HNCE1a cells, as are AcrD and AcrB. The complexes, however, were absent in cells expressing pDbL2 or pBdL1, again because these chimeras were presumably unstable, as seen with SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4).

We probed a similar blot with both antibodies (Fig. 3, panel III). The results were consistent with the blotting results with anti-AcrB (Fig. 3, panel I) or anti-AcrA alone (Fig. 3, panel II). In some lanes, it appeared that the possible AcrB oligomer band migrated more slowly than C1, but we need experiments with lower-cross-linked gels to confirm this tentative conclusion.

DISCUSSION

Some of the RND-type transporters, such as AcrB, catalyze the active efflux of a very wide range of compounds, including various detergents, dyes, and antibiotics (12). In addition, all RND transporters share an unusual topology, with two extremely large periplasmic loops, each containing around 300 amino acid residues (21). These observations make it very interesting and important to locate the transporter domain(s) that is involved in the substrate specificity.

In this study, we utilized the strong sequence similarity between AcrB and AcrD transporters of E. coli as well as their substantially different substrate ranges and examined the substrate specificity of various chimeras between AcrB and AcrD, constructed with precise, in-frame junctions by using a novel PCR-based method (5). The results showed that the replacement of the two large external loops of AcrD with the corresponding loops of AcrB (pDbL12 in Table 2) converted the substrate range of AcrD to the broader one that is characteristic of AcrB. In the converse experiment, replacement of the two large loops in AcrB with those of AcrD (pBdL12 and pDbT12 in Table 2) resulted in a transporter that had a narrower, AcrD-like substrate range. These results convincingly demonstrated that the large, periplasmic loops of the RND pumps AcrB and AcrD have a decisive influence on the substrate range of these proteins.

A trivial interpretation of the loop replacement data is that only the AcrB loops allow the transporter to interact with the MFP AcrA and thus allow the formation of the functional tripartite efflux complex. However, AcrD was shown to depend on AcrA for its efflux function with gradient plate analysis of the MIC in a ΔacrA host (Table 3) and to form chemical cross-links with AcrA (Fig. 3). (AcrA is known to interact with another RND transporter, AcrF, which is produced together with its own MFP partner, AcrE [7].) It is therefore likely that the large periplasmic loops do indeed play a major role in the recognition of substrates.

We tried to assess the relative importance of the L1 versus L2 domain by creating single replacement chimeras. However, the results were not easy to interpret, because a single replacement in the AcrD background (pDbL2) apparently created an unstable product (Fig. 3 and 4). However, a single loop replacement in the AcrB background (pBdL2) produced an AcrB-like pattern of resistance (Table 2), and this result was compatible with the hypothesis that L1 may be more important in determining the substrate specificity than L2. Nevertheless, firm conclusions cannot yet be reached because pBdL1 did not produce a stable protein (Fig. 4).

That L1 and L2 play a major role in the recognition of substrates is also consistent with the current view of the catalytic properties of the AcrB and AcrD transporters. Thus, the AcrAB-TolC complex is known to pump out mostly lipophilic and amphiphilic substrates (12). Although β-lactam substrates require lipophilic side chains for efficient export, the system exports substrates, such as carbenicillin, which cannot spontaneously cross the cytoplasmic membrane (15). AcrD extrudes totally hydrophilic substrates, aminoglycosides, which again do not readily cross the cytoplasmic membrane (20). All these observations can be understood if the RND-type transporter captures its substrates mainly from the periplasm, as predicted from the location of the substrate-binding (and recognition) domain in the periplasmic loop regions of the protein. The lipophilicity of the drug, or a portion of the drug, will allow the drug to partition into the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane and to become concentrated at the immediate vicinity of the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane. We can hypothesize that this preliminary concentration will aid in the capture of drug molecules by the RND transporters, from either the periplasm or the interface between the periplasm and the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane.

Finally, we have learned that the laboratory of Zgurskaya (23) used a somewhat different approach for the production of hybrids and reached a conclusion that is consistent with ours.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

A paper describing the crystal structure of AcrB has now appeared (S. Murakami, R. Nakashima, E. Yamashita, and A. Yamaguchi, Nature 419:587-593, 2002). The periplasmic domain of the AcrB trimer was found to have three holes or vestibules close to the membrane surface, and the authors suggest that these are the sites at which substrates are captured. These results are in complete agreement with the data presented in our study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-09644 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett, A. D., and W. V. Shaw. 1983. Resistance to fusidic acid in Escherichia coli mediated by the type I variant of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase. A plasmid-encoded mechanism involving antibiotic binding. Biochem. J. 215:29-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryson, V., and W. Szybalzski. 1952. Microbial selection. Science 116:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson, A. L., and H. Nikaido. 1991. Purification and characterization of the membrane-associated components of the maltose transport system from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8946-8951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiser, M., R. Cèbe, D. Drewello, and R. Schmitz. 2001. Integration of PCR fragments at any specific site within cloning vectors without the use of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase. BioTechniques 31:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George, A. M., and S. B. Levy. 1983. Amplifiable resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and other antibiotics in Escherichia coli: involvement of a non-plasmid-determined efflux of tetracycline. J. Bacteriol. 155:531-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi, K., N. Tsukagoshi, and R. Aono. 2001. Suppression of hypersensitivity of Escherichia coli acrB mutant to organic solvents by integrational activation of the acrEF operon with the IS1 or IS2 element. J. Bacteriol. 183:2646-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, J. E. Hearst, and H. Nikaido. 1994. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6299-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura, H. 1965. Gene-controlled resistance to acriflavin and other basic dyes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 90:8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikaido, H. 1996. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:5853-5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikaido, H. 1998. Antibiotic resistance caused by gram-negative multidrug efflux pumps. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:S32-S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikaido, H. 2001. Preventing drug access to targets: cell surface permeability barriers and active efflux. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:215-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikaido, H., M. Basina, V. Nguyen, and E. Y. Rosenberg. 1998. Multidrug efflux pump AcrAB of Salmonella typhimurium excretes only those β-lactam antibiotics containing lipophilic side chains. J. Bacteriol. 180:4686-4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikaido, H., and H. I. Zgurskaya. 1999. Antibiotic efflux mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 12:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5803-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okusu, H., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 1996. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178:306-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor, G. N., J. McKell, and R. H. Rownd. 1983. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase may confer resistance to fusidic acid by sequestering the drug. J. Bacteriol. 155:937-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg, E. Y., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 2000. AcrD of Escherichia coli is an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182:1754-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saier, M. H., Jr., I. T. Paulsen, M. K. Sliwinski, S. S. Pao, R. A. Skurray, and H. Nikaido. 1998. Evolutionary origins of multidrug and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. FASEB J. 12:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sulavik, M. C., C. Houseweart, C. Cramer, N. Jiwani, N. Murgolo, J. Greene, B. DiDomenico, K. J. Shaw, G. H. Miller, R. Hare, and G. Shimer. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1126-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tikhonova, E. B., Q. Wang, and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2002. Chimeric analysis of the multicomponent multidrug efflux transporters from gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:6499-6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng, T.-T., K. S. Gratwick, J. Kollman, D. Park, D. H. Nies, A. Goffeau, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1999. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 1999. AcrA from Escherichia coli is a highly asymmetric protein capable of spanning the periplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 285:409-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 1999. Bypassing the periplasm: reconstitution of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7190-7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 2000. Cross-linked complex between oligomeric periplasmic lipoprotein AcrA and the inner-membrane-associated multidrug efflux pump AcrB from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:4264-4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]