Abstract

In this report, we characterize the complete genome sequence of the temperate phage K139, which morphologically belongs to the Myoviridae phage family (P2 and 186). The prophage genome consists of 33,106 bp, and the overall GC content is 48.9%. Forty-four open reading frames were identified. Homology analysis and motif search were used to assign possible functions for the genes, revealing a close relationship to P2-like phages. By Southern blot screening of a Vibrio cholerae strain collection, two highly K139-related phage sequences were detected in non-O1, non-O139 strains. Combinatorial PCR analysis revealed almost identical genome organizations. One region of variable gene content was identified and sequenced. Additionally, the tail fiber genes were analyzed, leading to the identification of putative host-specific sequence variations. Furthermore, a K139-encoded Dam methyltransferase was characterized.

At present, 183 different tailed and 10 filamentous Vibrio phages have been described. On the basis of the morphotypes, the tailed phages were grouped into seven basic forms belonging to the families of tailed phages (Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae) and the filamentous phages were typed to the Inoviridae family (1). Due to the importance of the filamentous phage CTXφ for the virulence of Vibrio cholerae, sequencing efforts have been focused mainly on this group of phages (CTXφ [56], fsl [26], and fs-2 [27]). To our knowledge, K139 is the first tailed vibriophage for which information for the entire sequence is available. K139 was originally isolated from the V. cholerae serogroup O139 (48), which emerged for the first time in 1992 as the causative agent of cholera epidemics (1a). Subsequently, we found that the phage can also be recovered very frequently from various V. cholerae strains of serogroup O1 biotype El Tor. The observation that nonlysogenic O139 strains could not be infected with K139 was confirmed by the identification of the O1 antigen as the primary phage receptor (41). Analysis of the lysogeny-lysis switch genes already indicated a relationship to P2-like phages (40), which belong morphologically to the Myoviridae family. Members of this phage group (Escherichia coli phages P2 and 186 [14], Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage φCTX [39], and Haemophilus influenzae phages HP1 [15] and HP2 [direct submission, GenBank accession no. NC_003315]) typically contain approximately 31- to 36-kb double-stranded DNA with single-stranded cohesive ends, but several subgroups, defined by the presence of differently derived genes, exist. For example, HP1 and HP2 contain tail genes different from those of the P2/186/φCTX group, whereas φCTX differs from all P2-like phages in its content of the early and delayed early genes. The evolution of such mosaic-like phage genomes may result from horizontal exchange of whole functional units (modules) (7) or of smaller units (single genes or gene fragments) acquired from a common gene pool shared by all double-stranded DNA tailed bacteriophages (24).

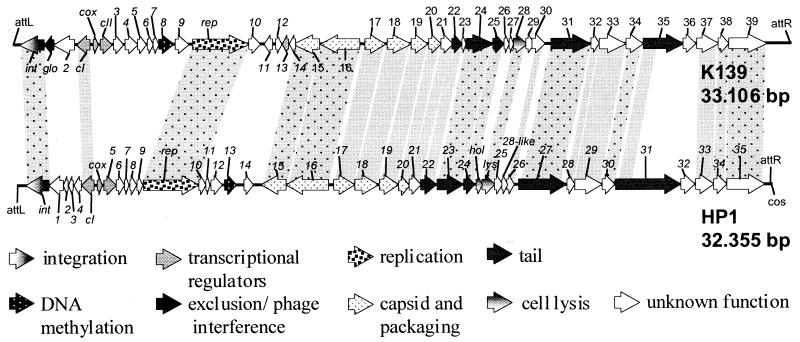

FIG. 1.

Genome structure of phage K139 and comparison with the related bacteriophage HP1. The functions of the products of the ORFs are indicated by the arrows as described at the bottom. Homolog ORFs are connected by gray boxes. Gray shading alone symbolizes homology on the protein level; dotted gray shading additionally indicates homology on the nucleotide level (Table 1).

Here we completely sequenced the K139 phage genome. The deduced open reading frames (ORFs) were gathered into functional gene groups, and genes for some major expressed capsid and tail proteins and a Dam methylase were identified. By screening and identification of related prophages, regions of variable gene content as well as the presumed tail fiber genes were sequenced. The latter revealed the presence of two variable segments within the deduced tail fiber protein, which we propose determines the host range of the phage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phages, bacterial strains, and growth media.

Phage K139 was originally isolated from V. cholerae O139 strain MO10 (48) and subsequently propagated on O1 El Tor strain MAK757 (36). Plaque inhibition assays were performed with the highly lytic phage mutant K139.cm9 (40). Different V. cholerae isolates, including environmental non-O1, non-O139 strains (42) were used to screen for K139 cross-hybridizing fragments. Analysis of K139-related sequences was performed with chromosomal DNA of V. cholerae strains E8498 (O141) (58), Ch457 (non-O1, non-O139) (6), and O395 (O1 classic) (36). E. coli strains MC4100 (8), DH5α (22), and GM2163 (New England Biolabs, Schwalbach, Germany) were used for recombinant DNA constructions. Cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, LB agar, and tryptone broth (TB) top agar (37) at 37°C. The following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentrations: kanamycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12 μg/ml). Blue-white screening was performed on LB agar plates supplemented with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 1 mM) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (40 μg/ml). For phage propagation, the growth medium was supplemented with CaCl2 (10 mM).

Recombinant DNA constructions.

EcoRV-restricted K139 genome fragments were subcloned into pACYC184 (49). For sequencing, the PCR products of the K139-related phages were ligated into the pGEM-TEasy system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Overexpression of orf8 was achieved by subcloning a BspHI/SalI-flanked PCR fragment of orf8 (without promoter and Shine-Dalgarno sequences) into the pTrc99Akan vector (40). The synthetic oligonucleotides used for subcloning were as follows: orf8BspHI (5′-AAAATCATGAGCTCAACCAACGGCG-3′) and orf8SalI (5′-TTTTGTCGACTCATGCGGCCTCCCTTTTG-3′), with the BspHI and SalI sites underlined, were used for subcloning of orf8; orf15-3′out (5′-ATTCCGGTGTGCAAGCGTTT-3′) and rep-3′out (5′-AGAACATTCACAACCAGACC-3′) were used for subcloning of the K139-related sequences corresponding to the K139 genome region between rep and orf15.

DNA purification, PCR, and sequencing.

The method used for purification of phage particles and phage DNA has been described previously (40). Chromosomal DNA was prepared by using a method modified from that of Grimberg et al. (19) as described elsewhere (41). PCRs for sequencing and subcloning were carried out using the TripleMaster system (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). DNA sequencing was performed with the LiCor automated sequencing system (MWG Biotech GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany) and with an ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). The entire phage DNA was sequenced at least twice for one strand and once for the other strand by using 95 synthetic oligonucleotides for the K139 sequence and an additional 17 oligonucleotides for determination of the K139-related sequences (details not shown). The DNA sequence of the genome of phage K139 was mainly determined by primer walking of the DNA isolated from phage particles. To accelerate the sequencing process, five defined EcoRV phage fragments were subcloned into plasmid pACYC184 (49) and were then used as templates for further sequencing. Additionally, one end (right end shown in Fig. 1) of the phage genome was PCR amplified by utilizing genomic DNA of K139-lysogenized cells with a phage-specific primer and a primer located near the phage attachment site on the host chromosome (40). The sequences of the K139-related phages were determined either directly from PCR products or from PCR products subcloned into the pGEM-TEasy plasmid (Promega), utilizing the M13 uni and M13 reverse primers for initial sequencing.

Southern hybridization.

Southern blotting was performed as previously described by Southern (52). Briefly, chromosomal DNA was digested with HindIII, separated on an agarose gel (0.7%), and transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). DNA probe labeling and hybridization were performed with the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The washing steps were performed at 42°C in a buffer containing saline citrate (0.5%) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (0.4%).

LPS preparation and plaque inhibition assay.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was prepared by using the hot phenol-water method of Slauch et al. (50), separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (30), and silver stained as described previously (55). The concentration was best-fitted by SDS-PAGE analysis and comparison with a defined concentration of LPS derived from V. cholerae 569B (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany). Different concentrations of purified LPS were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 104 PFU of K139.cm9/ml in 1 ml of LB broth. Five, 10, and 50 μl of this mixture together with 100 μl of a MAK757 overnight culture were added to 8 ml of TB top agar and poured on LB agar plates. Plaques were counted after 6 h of incubation at 37°C.

Bioinformatic analysis.

Contig alignment was performed with ABI Prism Auto Assembler 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). ORFs were identified with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ORF finder tool and subsequently subjected to database searches using the BlastX (version 2.2.3) (2) and FastA (version 3.3t08) (45) programs. The 5′ regions were then checked for the presence of ribosome binding sites as described by Stormo et al. (53). DNA sequence and protein feature analysis was carried out with the following tools. The NPS@ Web server (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_hth.html) (13) and the Wisconsin Package program, version 10.1, of the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.) were used to detect helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs. Transmembrane domains and signal sequences were detected by using the Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (CBS) server available at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ (TMHMM [51] and SignalP [43]), the SOSUI server available at http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/welcomeE.html (SosuiTMH and SosuiSignal), and the ISREC TMpred server available at http://www.ch.embnet.org. Protein motifs were searched at the GenomeNet server (http://motif.genome.ad.jp/). Multiple-sequence alignment was performed with ClustalW 1.8 from the BCM Search Launcher site (http://searchlauncher.bcm.tmc.edu/), and pairwise alignment was performed with the BLAST 2 program at the NCBI web site (54). Promoters were detected by determination of similarity to E. coli σ70 promoters (38).

Isolation and identification of phage K139 proteins.

For protein preparations, K139 particles were isolated and prepared as described previously (40, 48). The phage pellet was resuspended in phage buffer (20 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and purified by centrifugation (25,000 rpm for 3 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW28 rotor) in a CsCl step gradient (1.4 g/ml and 1.2 g/ml). For two-dimensional (2D) SDS-PAGE and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) analysis, two UV-reactive bands were collected and separately centrifuged (55,000 rpm for 18 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW60 rotor) in a second CsCl gradient (1.4 g/ml). The CsCl fractions were dialyzed against 5 liters of phage buffer for 48 h at 4°C. Two main phage fractions isolated from CsCl gradients were concentrated, and the buffer was exchanged with isoelectric focusing (IEF) sample buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, 0.4% dithioerythritol) by diafiltration (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The 2D SDS-PAGE was carried out as described previously (5). IEF was performed using IPG strips with an immobilized pH gradient from 3 to 10 (ReadyStrips; Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) on a Multiphor electrophoresis apparatus (Amersham-Pharmacia), followed by SDS-PAGE using gradient (8 to 16%) gels (Criterion; Bio-Rad) (8.0 cm by 13.5 cm by 1.0 mm). Identification of the proteins was carried out by peptide mass fingerprinting as described previously (20) utilizing trypsin-digested material for MALDI mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). For protein identification, the SWISS-PROT database and all translated ORFs from the K139 sequence were searched. As a criterion for phage protein identification, four to five peptides had to match the theoretical value in the phage and V. cholerae protein database.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The K139 sequence presented in this study has been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. AF125163. The sequences of the K139-related phages were assigned accession no. AY147031 to AY147036.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

K139 genome and comparison to P2-like phages.

The complete K139 prophage genome comprises 33,106 bp. The overall GC content is 48.9% and is therefore only slightly higher than the average GC content of V. cholerae chromosome 1 (47.7% [23]), which contains the phage attachment site (40). The DNA sequence of the immunity (imm) region has been published previously (40) and has been shown to overlap by about 700 bp with the DNA sequence portion of a putative vibriophage from O1 El Tor strain V86 (GenBank accession no. AF008938).

The K139 phage genome contains 44 ORFs. Twenty-six ORFs showed considerable homology to ORFs in P2-like phages, especially to HP1 (Fig. 1) and HP2 of H. influenzae, 186 and P2 of E. coli, and φCTX of P. aeruginosa (Table 1). The ORFs of K139 are organized in seven putative transcriptional units. The genomic organization of the tail morphogenesis and lysis cluster also reveals a closer relationship to HP1. The two phages thus form their own subgroup distinct from P2/186/φCTX (15) (Table 1). As demonstrated by homology analysis, the capsid gene cluster in all known P2-like phages is most conserved with regard to structure and similarity. This might reflect the function of the capsid as a mere DNA container, with little need for adaptation to different hosts. In contrast, genes involved in tail formation show a greater divergence; those of K139 are more closely related to those of HP1 than to those of P2. In the early operons, genes for two basic functions of phage development, integration and replication, are conserved in position and sequence, whereas other genes located in the lysogenic and early lytic operons (accessory replication genes, methyltransferase genes, exclusion and phage interference ORFs, and other uncharacterized ORFs) seem to be totally unrelated or are highly divergent from each other. A similar genome structure is seen in the highly related K139 phages and is discussed below. The following highlights some functional gene groups of the K139 genome.

TABLE 1.

ORFs of the K139 genome and presumed characteristics determined by similarity and motif search

| ORF | Position

|

Protein size (kDa) | pI | RBS rulesa (unusual start codon) | Presumed function(s) | Related protein(s) or gene (phage or organism) | GenBank accession no. | % Identity (BlastP) | E value | Motif(s)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||||||||

| int | 1271 | 237 | 39.5 | 9.7 | 0.5 | Integrase | Int (186), Int (P2), Int (HP2), Int (S2), Int (HP1), many others | P06723P36932AAK37784CAA96221P21442 | 39 37 38 38 37 | 1e-66 1e-53 9e-53 7e-52 8e-52 | HTH |

| glo | 1684 | 1274 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 0.5 | Exclusion | SP | ||||

| 2 | 2589 | 1687 | 33.8 | 4.9 | 3 | ||||||

| cI | 3262 | 2618 | 24.3 | 6.6 | 3 | Regulator | STM2738 (Fels-2), CI (186), Orf1 (retron Ec67), CI (Salmonella enterica) CI (S2), CI (HP1), CI (HP2) | AAL21624S09533P21323CAD09421CAA96223P51704AAK37786 | 24 36 28 25 24 23 24 | 7e-7 4e-5 3e-4 0.001 0.005 0.008 0.026 | |

| cox | 3408 | 3617 | 7.8 | 8.8 | 7 | Regulator | CoxT (CP-933T), STY3661 (S. enterica), OrfA (Ec67), Orf2 (S2) | AAG56902CAD09422P21315CAA96224 | 46 42 40 34 | 1e-7 7e-4 0.006 0.019 | |

| cII | 3731 | 4267 | 19.6 | 6.7 | 7 | Regulator | CII (186), CII (S. enterica), STM2736 (Fels-2), CII (S. enterica), OrfB (Ec67) | P21678CAD06763AAL21622CAD09423P21316 | 28 35 33 37 35 | 9e-11 2e-8 2e-8 2e-7 4e-7 | HTH |

| 3 | 4283 | 4714 | 16.4 | 9.3 | 7 | Replication | B (P2) | P07696 | 28 | 0.37 | |

| 4 | 4794 | 5330 | 20.1 | 4.8 | 6 | ||||||

| 5 | 5330 | 5641 | 11.5 | 6.0 | 6 | ||||||

| 6 | 5741 | 5983 | 9.3 | 4.4 | 7 | ||||||

| 7 | 5989 | 6213 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 6 | ||||||

| 8 | 6213 | 6827 | 23.0 | 7.6 | 6 | DNA methyltransferase | L7082 (E. coli O157:H7), YdcA (Shigella flexneri) | BAA31804BAA78824 | 29 29 | 2e-4 4e-4 | N6MTFRASE |

| 9 | 6934 | 7482 | 21.1 | 9.4 | 7 | ||||||

| rep | 7698 | 10097 | 92.6 | 6.9 | 0 (GTG) | Replication | A (186), Rep (HP1), Rep (HP2), A (P2), many others | P41064P51711AAK37793S33835 | 41 30 30 36 | 4e-92 4e-64 1e-63 2e-56 | |

| 10 | 10110 | 10643 | 20.9 | 7.8 | 7 | MW0374 (Staphylococcus aureus), Alr1266 (Nostoc sp.) | BAB94239BAB73223 | 36 30 | 8e-6 0.001 | ||

| 11 | 11058 | 10723 | 12.5 | 8.0 | 6 | HTH | |||||

| 12 | 11296 | 12538 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 7 | ||||||

| 13 | 11793 | 11545 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 4 | Regulator | RSc0964 (Ralstonia solanacearum), Orf34 (φCTX) | CAD14666BAA36262E82407 | 35 28 57 | 0.006 0.037 8e-14 | Zinc finger |

| 14 | 12079 | 11867 | 7.9 | 4.6 | 6 | VCA0868 (V. cholerae) | E82407 | 57 | 8e-14 | ||

| 15b | 13109 | 12066 | 39.3 | 6.6 | 0.5 | Capsid portal protein | Orf15 (HP2), Orf15 (HP1), Orf1 (φCTX), W (186), Q (P2), many others | AAK37797P51717BAA36227.1AAC34146P25480 | 44 44 35 32 34 | 3e-75 2e-74 2e-42 1e-40 1e-39 | HTH |

| 16 | 14923 | 13109 | 69.0 | 7.3 | 0.5 | Terminase, ATPase subunit | Orf16 (HP1), Orf16 (HP2), Orf2 (φCTX), P (P2), Orf12 (186), z57r (V. cholerae), W (186), many others | P51718AAK37798BAA36228.1P25479AAC34148CAA13158AAC34147 | 49 49 45 42 41 98 33 | e-168 e-168 e-135 e-124 e-120 2e-97 2e-24 | HTH |

| 17b | 15097 | 15993 | 33.7 | 4.7 | 0.5 | Capsid scaffolding protein | Orf17 (HP2), Orf17 (HP1), V (186), Orf3 (φCTX), many others | AAK37799P51719S25272BAA36229 | 38 37 45 45 | 2e-33 5e-32 1e-22 4e-22/PICK> | |

| 18b | 16033 | 17055 | 37.8 | 8.8 | 7 | Major capsid protein | Orf4 (φCTX), T (186), N (P2), Orf18 (HP1), Orf18 (HP2), many others | BAA36230AAC34150P25477P51720AAK37800 | 32 27 29 29 28 | 2e-33 2e-25 4e-25 8e-20 7e-19 | HTH |

| 19 | 17058 | 17771 | 27.1 | 7.0 | 6 | Terminase, endonuclease subunit | Orf19 (HP1), Orf19 (HP2), Orf5 (φCTX), M (P2), R (186), many others | P51721 AAK37801 BAA36231P25476AAC34151 | 34 34 28 26 25 | 9e-28 3e-27 1e-11 4e-9 5e-8 | SP |

| 20b | 17881 | 18339 | 16.8 | 5.4 | 3 | Head completion protein | Orf20 (HP1), Orf20 (HP2), Orf6 (φCTX), Q (186), L (P2), many others | P51722AAK37802BAA36232.1AAC34152P25475 | 36 33 30 28 27 | 3e-19 5e-17 2e-8 2e-8 2e-7 | |

| 21b | 18339 | 18824 | 18.7 | 4.6 | 6 | Orf21 (HP2), Orf21 (HP1) | AAK37803P51723 | 32 32 | 4e-12 6e-11 | ||

| 22 | 18814 | 19311 | 19.2 | 11.0 | 0.5 | Tail completion protein | Orf22 (HP1), Orf22 (HP2), Orf14 (φCTX), O (186) | P51724AAK37804BAA36241.1AAC34159 | 26 25 27 26 | 3e-5 0.003 0.018 0.34 | |

| 23 | 19311 | 19469 | 6.2 | 11.3 | 1 | ||||||

| 24 | 19474 | 20580 | 40.4 | 4.8 | 7 | Tail sheath protein | Orf23 (HP2), Orf23 (HP1) | AAK37805P51725 | 42 42 | 2e-68 8e-68 | |

| 25b 26 | 20583 21056 | 21038 21262 | 16.9 7.9 | 5.7 7.6 | 5 5 | Tail tube protein | Orf24 (HP1), Orf24 (HP2) Orf79 (VT2-Sa), L0141 (933W), Orf39 (φCTX), Orfa49 (Stx2 phage-I), Orf80 (186), many others | P51726AAK37806BAA84362AAD25484BAA36267BAB87944AAC34182 | 50 50 38 38 35 37 33 | 8e-35 3e-33 7e-7 le-6 1e-4 2e-4 0.002 | C4 type Zinc finger |

| 27 | 21262 | 21486 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 7 | TMH | |||||

| 28 | 21476 | 22060 | 21.4 | 8.5 | 4 | Lysozyme | YPO2098 (Yersinia pestis), Gp17 (P1), Lys (HP1), Lys (HP2), many others | CAC90911CAA61013P51728AAK37808 | 43 36 36 35 | 2e-32 2e-26 6e-23 2e-21 | SP, TMH |

| 29 | 22029 | 22376 | 12.8 | 7.9 | 0.5, 3 | TMH, SP | |||||

| 30 | 22288 | 22863 | 21.5 | 9.0 | 6 | Orf26 (HP1), Orf26 (HP2), ebiG1476 (Anopheles gambiae) | S69534AAK37810EAA02260 | 39 39 34 | 2e-7 2e-7 4e-6 | SP | |

| 31 | 23063 | 24877 | 63.6 | 4.5 | 0.5 | Tail length determinator | Orf27 (HP1), Orf27 (HP2), T (P2), G (186), Orf25 (φCTX), many others | P51731AAK37811AAD03293AAC34170BAA36253.1 | 49 46 24 22 25 | 8e-99 1e-98 2e-16 2e-11 6e-11 | TMH |

| 32 | 24870 | 25199 | 12.1 | 4.8 | 3 | Orf28 (HP2), Orf28 (HP1) | AAK37812 P51732 | 45 45 | 3e-19 4e-19 | ||

| 33 | 25199 | 26395 | 43.5 | 4.9 | 6 | Orf29 (HP2), Orf29 (HP1) | AAK37813 P51733 | 39 39 | 2e-76 8e-69 | ||

| 34 | 26395 | 27051 | 25.6 | 6.3 | 6 | ebiP1697 (A. gambiae), Orf30 (HP1), Orf30 (HP2) | EAA02286P51734AAK37814 | 65 52 52 | 2e-45 2e-36 2e-36 | ||

| 35b | 27051 | 28910 | 67.6 | 5.3 | 3 | Tail fiber protein | Orf31 (HP1), Orf31 (HP2), Atul187 (Agrobacterium tumefaciens), z55f gene (V. cholerae)c | P51735AAK37815AAL42199AJ231114 | 33 33 38 69 | 2e-35 2e-33 2e-9 9e-12 | |

| 36 | 28913 | 29434 | 20.3 | 4.5 | 6 | Tail fiber assembly | Gp29 (HK97) | AAF31112.1 | 26 | 0.02 | |

| 37 | 29440 | 30330 | 31.9 | 7.1 | 6 | Orf33 (HP1), Orf33 (HP2) | P51737AAK37817 | 26 27 | 1e-10 3e-10 | ||

| 38 | 30321 | 30791 | 17.5 | 8.8 | 7 | Orf34 (HP2), Orf34 (HP1) | AAK37818P51738 | 34 34 | 1e-21 1e-21 | ||

| 39 | 30791 | 32419 | 60.3 | 5.5 | 0 (GTG) | Orf35 (HP2), Orf35 (HP1) | AAK37819P51739 | 33 33 | 1e-91 2e-90 | ||

| O395 orf14a | 18.5 | 9.0 | 7 (TTG) | yhaV (E. coli), slr0725 (Synechocystis sp.) | P42901BAA16672 | 46 36 | 6e-19 1e-15 | ||||

| O395 orf14b | 7.3 | 5.8 | 5 | ||||||||

| O395 orf14c | 25.9 | 9.2 | 7 | YPO2093 (Y. pestis), P43 (APSE-1), XF0704 (Xylella fastidiosa) | CAC90906AAF03986AAF83514 | 43 44 39 | 2e-17 2e-17 1e-12 | ||||

| V205 orf14d | 21.4 | 5.2 | 0.5 | MM3036 (Methanosarcina mazei), RSp1626 (R. solanacearum) | AAM32732CAD18777 | 29 31 | 4e-12 1e-6 | Acetyltransferase | |||

| V205 orf14e | 8.7 | 10.4 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| V209 orf10a | 28.2 | 9.1 | 5 (TTG) | ||||||||

Ribosome binding site (RBS) rules according to Stormo et al. (53).

Identified by MALDI-TOF.

FastA database search.

SP, signal peptide; HTH, helix-turn-helix motif; TMH, transmembrane motif.

DNA methylation.

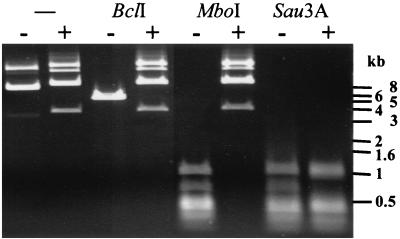

Of the P2-like phages, only HP1 is known to code for a methyltransferase (MTase) (15, 46). Although ORF8 of K139 shows no similarity to the HP1 MTase, it contains the same N6 adenine-specific DNA methylase signature (Table 1). To test for an MTase function, ORF8 was overexpressed in the dam dcm E. coli strain GM2163. A total inhibition of restriction of plasmid and chromosomal DNA was observed with the enzymes BclI (TGATCA) and MboI (GATC) (Fig. 2), which are sensitive to adenine methylation (35), whereas there was no inhibition of Sau3A, which is a methylation-resistant isoschizomer of MboI. These findings indicate that the K139 MTase ORF8, like the HP1 MTase, methylates adenine in the sequence 5′-GATC-3′. Partial inhibition of the enzymes ClaI (ATCGAT) and EcoRV (GATATC) (data not shown) indicate methylation of noncanonical sequences. It has been shown previously that at high enzyme concentrations the T4 MTase, which also methylates 5′-GATC-3′, methylates the 5′-GAT-3′ and 5′-GAC-3′ sequences as well (29). Like the HP1 MTase, K139 ORF8 can be classified into the γ group of N6 adenine MTases on the basis of the presence and order of amino acid sequence motifs as described by Malone et al. (34). The exact function of the K139 MTase for phage biology remains to be elucidated. GATC sequences are located on inverted repeats between the PR and PL promoters and on direct repeats adjacent to the proposed packaging site (data not shown), which suggests a possible regulatory role for gene expression and packaging.

FIG. 2.

DNA methylation is produced by ORF8. Shown are the results of restriction analysis of plasmid DNA derived from an orf8-overexpressing E. coli strain GM2163. The first two lanes show unrestricted DNA, and subsequent lanes show BclI, MboI, and Sau3A restriction, as indicated. DNA isolated from strains with the pTrc99Akan plasmid alone are marked with a minus sign, and DNA isolated from strains harboring the pTrc99Akanorf8 plasmid are marked with a plus sign. The BclI-restricted control plasmid has a molecular size of 5.5 kb, and the orf8-overexpressing plasmid should be restricted to fragments of 4.8 and 1.3 kb. Sau3A and MboI are isoschizomers, so the restricted DNAs should be of equal length.

DNA replication.

The predicted Rep protein of phage K139 is similar to the replication proteins of many phages, including Rep of HP1 and HP2 and protein A of phages 186 and P2 (Table 1), which are known to replicate by a modified unidirectional rolling circle mechanism, producing covalently closed monomeric circles which are substrates for DNA packaging (3). Comparisons of many rolling circle replication (RCR) proteins led to the identification of three conserved motifs (28). The common orientation of these motifs and the presence of two tyrosine residues within motif 3 are characteristic of superfamily I of the Rep class of RCR proteins, which contains, among others, the replication proteins of the P2-like phages. We compared the replication protein of K139 with the respective proteins of P2, 186, and HP1 in a multiple-sequence alignment and were able to identify the same conserved motifs within the K139 Rep protein (data not shown). The conservation of these sequence motifs, including the two tyrosine residues, which were shown to be part of the active site of the P2 A protein (44), suggests that K139 also replicates via this modified RCR mechanism. If this is the case and K139 thus also produces monomeric circles as packaging substrates, then this would suggest cos site packaging like that in the other P2-like phages. However, Tn10d-bla insertions close to the ends of the linear phage genome indicated terminal redundancy of the packaged DNA as described previously (48), and this is now confirmed by the sequence determination.

The crucial step for the initiation of replication is the formation of a free 3′-hydroxyl (3′-OH) moiety at the replication origin (ori), which serves as a primer for the DNA polymerase activity. P2 was shown to provide this 3′-OH end by introducing a sequence-specific, single-stranded cut at the replication origin (9), which was located within the coding sequence of the A gene itself (32). Interestingly, in a BLAST 2 alignment with the P2 A gene, the rep gene of K139 was found to be 90% identical to a small region of the A gene (30 bp), which corresponds to the mapped origin of replication in P2. The same region of K139 rep is also 94% identical to a small sequence of the A gene of phage 186 (data not shown), which is also in good accordance with the location of the 186 ori estimated by electron microscopy studies (10). The conservation of this small region suggests the same location for the ori sites within these phages and could possibly reflect a common binding specificity for the related replication proteins. Another putative replication protein, ORF3 (Table 1), seems to represent protein B of P2, which is needed for lagging-strand synthesis during lytic replication (17).

Capsid and DNA packaging genes.

On the basis of their similarity to genes of the well-characterized phages P2 and 186, four ORFs of K139 were assigned roles in capsid formation. ORF15 shows similarity to capsid portal proteins (Table 1), and ORF17 shows similarity to capsid scaffolding proteins. ORF18 was assigned as the major capsid protein; accordingly, we identified it as the most abundant virion protein by 2D SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF analysis (data not shown). The last gene of the capsid morphogenesis cluster, orf20, is similar on the amino acid level to head completion proteins. All of the presumed capsid proteins, ORF15, ORF17, ORF18, and ORF20, were identified by 2D SDS-PAGE and subsequent MALDI-TOF analysis of phage particles (data not shown), confirming their proposed function in morphogenesis.

DNA packaging into proheads is accomplished by the terminase enzyme, which consists of two subunits, a smaller one with DNA-binding activity and a larger one with ATPase and endonuclease activity (16). ORF16 and ORF19 of K139 are similar to the large and small subunits, respectively (Table 1). Bioinformatic analysis of ORF16 revealed the presence of helix-turn-helix DNA binding motifs, which could be consistent with the proposed endonuclease function. ORF16 was also found to be 98% identical to a hypothetical 20-kDa Z57r protein of V. cholerae strain Z17561, which could be a fragment of a vibriophage within this strain.

Tail genes.

As discussed above, K139 and HP1 share almost the same set of presumed tail genes. ORF21 shows homology only to the uncharacterized orf21 gene product of HP1, and its presence in the K139 virion particle was revealed by MALDI-TOF analysis (data not shown). ORF22 is similar to the tail completion proteins, which were shown to be essential for tail production (15). ORF24 and ORF25 could potentially encode the tail sheath and tail tube proteins, respectively, according to their homology to HP1 proteins (Table 1). ORF25 can be identified by MALDI-TOF analysis, suggesting that this protein has a morphological function. ORF31 probably encodes the presumed tail length determinator, which is believed to span the entire length of the tail tube (31). ORF35 could also be identified by MALDI-TOF analysis as a structural protein of the phage particle. Determination of its similarity revealed that it encodes the tail fiber protein of K139. The tail fibers are thought to be involved in receptor binding, and they have been shown to consist of variable modules, reflecting the different binding specificities of the tail fibers (for a review, see reference 21). This modular structure could also be confirmed for the presumed tail fiber genes of K139 and of highly related V. cholerae phages (discussed in more detail below). Finally, as in other P2-like phages, we found an ORF with similarity to a putative tail fiber assembly protein of HK97 downstream of the presumed tail fiber of K139.

Cell lysis.

The cell lysis gene cluster of the P2-like phages harbors genes encoding holin, endolysin, and one or two lysis accessory proteins (LysA and LysB) and a small ORF with unknown function (47). K139 ORF28 is the only gene product, which is predicted by homology to act in cell lysis. It shows similarity to muramidases of a great number of phages (Table 1). Interestingly, protein sequence analysis revealed that it could contain a signal sequence or a putative transmembrane helix, as has been reported for other endolysins (12, 25, 33). Therefore, the K139 endolysin might represent either a membrane or secreted protein. If we use the criteria described by Wang et al. (57) to search for possible holins, then ORF27 would be a likely candidate. It is a small protein (75 amino acids), is predicted to contain transmembrane domains, and has a highly charged and hydrophilic C-terminal sequence (data not shown). ORF30 is 39% identical to ORF26 of HP1, which is encoded at an equivalent position downstream of the lysozyme. Esposito et al. (15) have suggested that orf25 and orf26 of HP1 code for lysis accessory proteins. The sequence properties of ORF29 and ORF30 would also fit such a function, because they are predicted to contain a transmembrane domain and a signal peptide, respectively.

K139-related phages.

To determine the occurrence of K139 or related phages within different V. cholerae strains, we screened a diverse V. cholerae strain collection consisting of different serogroups (42) by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Four different hybridization patterns could be identified: type 1 in O1 El Tor and O139 strains, type 2 in the O1 classical strain O395, type 3 in the O141 strain E8498, and type 4 in the non-O1, non-O139 strain Ch457. The presence of a defective prophage in the O1 classic strain O395 has already been reported (18), and it was later identified as a K139-related phage (48). We further characterized the different phage types by PCR analysis, checking for gene content and gene order and finding an almost identical overall genome organization, indicating a close relationship (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PCR of K139 and related prophages

| Genomic region in K139 | PCR fragment size (kb)a for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K139 | O395 | Ch457 | E8498 | |

| int to glo | 0.4 | + | + | + |

| glo to cox | 1.9 | + | + | NOc |

| orf2 | 0.9 | + | + | + |

| cI | 0.7 | + | NO | + |

| cI to cII | 1.4 | + | + | + |

| orf3 to orf9 | 3.1 | + | + | + |

| rep | 2.3 | + | + | + |

| rep to orf15 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| orf15 to orf16 | 2.4 | + | + | + |

| orf16 to orf20 | 3.4 | + | + | + |

| orf20 to orf25 | 2.7 | + | + | + |

| orf26 to orf31 | 3.7 | + | + | + |

| orf32 to orf35 | 2.6 | + | + | NO |

| orf32 to orf39 | 7.5 | NDb | ND | + |

| orf34 to orf35 | 1.9 | + | + | + |

| orf35 to orf36 | 1.6 | + | + | + |

| orf37 to orf39 | 2.9 | + | + | + |

Unless noted otherwise, the positive (+) PCR fragments of the K139-related prophages were of the same length as that of K139.

ND, not determined.

NO, not observed.

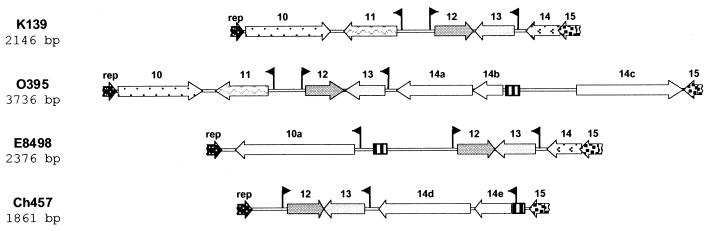

The most striking difference was detected within the region corresponding to the sequence of K139 from rep to orf15 (Fig. 3). In K139, this genomic region harbors five genes. Only two of these ORFs, orf12 and orf13, are present in all investigated phage sequences; thus, they seem to be involved in essential phage functions. ORF13 is a homolog of the family of C4-type zinc finger activators of late gene expression (Table 1), whereas ORF12 shows no homology to proteins in the database. Another 6 of the 1 presumed ORFs identified in the different phage sequences are similar only to hypothetical phage or bacterial proteins. Several recombinational processes became obvious when we compared the sequences. K139 and O395 share the genes from rep to orf13 (98% identity on the nucleotide level), while orf14 of K139 is replaced in O395 by a 1.8-kb sequence harboring at least three ORFs. On the other hand, a sequence containing a K139 orf14 homolog can be found in E8498 (96% DNA identity). It seems likely that these phage sequences have a common history, since we also observed that the phage harbored by strain E8498 (serogroup O141) has the same tail fiber gene as K139; therefore, it previously may have been derived from an ancestor O1 strain (see below). Comparison of the orf12 and orf13 sequences of all investigated phages also revealed recombinational processes in the past (Table 3). Two versions of ORF12 exist, showing 50% homology to each other; one is present in K139 and O395, and the other is present in Ch457 and E8498. The ORF13 sequence also reveals the same pattern, although the overall similarity is much higher than for ORF12. Additional recombination processes took place in E8498 and Ch457, which led to the incorporation of different ORFs, left of orf12 in E8498 and right of orf13 in Ch457. Finally, we identified a homolog sequence, which is about 84% identical over a length of 130 bp in Ch457 and E8498 and over 89 bp in O395, amidst an otherwise unrelated region (Fig. 3). This small sequence could be a relic of the original phage sequence, which was then carried away and became shortened by different exchange processes. On the other hand, these sequences could provide the possibility for homologous recombination, as recently described by Clark et al. (11) for the linker sequences of coliphage HK620, leading to a facilitated distribution of genes originally acquired through illegitimate recombination.

FIG. 3.

Genomic sequence comparison of K139-related phages. The sequence of K139 from rep to orf15 was compared to corresponding sequences of phages from V. cholerae strains O395, Ch457, and E8498. Only fragments of the rep and orf15 sequences are shown. ORFs with the same pattern are homologs. The striped box indicates a short DNA sequence with 84% identity between strains O395, Ch457, and E8498. Presumed promoter sequences are indicated by arrow flags.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid identities of ORF12 and ORF13 homologs of K139 and related phages determined by BLAST 2 alignment

| Phage | % Identity with ORF12 of phage:

|

% Identity with ORF13 of phage:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K139 | O395 | Ch457 | K139 | O395 | Ch457 | |

| O395 | 97 | 98 | ||||

| Ch457 | 50 | 48 | 92 | 91 | ||

| E8498 | 50 | 48 | 97 | 93 | 92 | 95 |

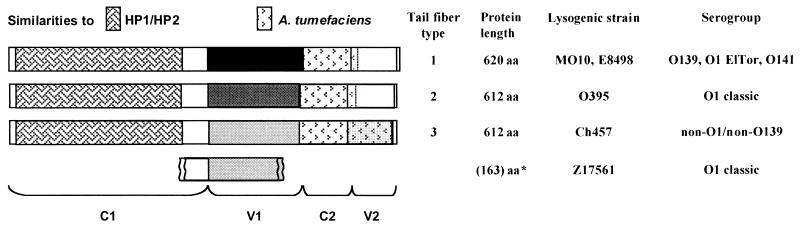

Another hot spot for exchange processes is represented by the phage tail fiber genes. The tail fibers are involved in binding of the phage to its host receptor structures. K139 has been shown to bind to the O1 antigen of V. cholerae (41). Sequencing of the presumed tail fiber genes of the investigated phages revealed a mosaic-like structure (Fig. 4), as has also been reported for other phages (for a review, see reference 21). Two conserved (C1 and C2) and two variable (V1 and V2) regions were identified. The C1 region constitutes almost the whole N-terminal half of the protein, whereas the C2 region is located between V1 and the C-terminal V2 region. Different combinations of the variable regions define the three types of tail fiber proteins presently known. A type 1 tail fiber is present in phages hosted by serogroups O1 El Tor, O139, and O141; a type 2 tail fiber can be defined in a phage sequence derived from O1 classic strain O395; and a type 3 tail fiber is found in a phage sequence derived from the non-O1, non-O139 strain Ch457. A database search led to the identification of a presumed tail fiber fragment in the O1 classic strain Z17561 (GenBank accession no. AJ231114), which corresponds to the end of the C1 region and the main part of V1. The discovery of these different tail fiber types raises some interesting questions. Since the C-terminal part of the tail fiber is thought to be involved in receptor binding (21), one could speculate that the variable regions of the K139-related phages determine their binding ability to different O-antigen receptors. Interestingly, tail fiber type 1 (which corresponds to the K139 tail fiber type) is present in three different serogroups (O1 El Tor, O139, and O141). However, K139 is not able to bind to purified O139 LPS (41), nor could it bind to purified O141 LPS of strain E8498 in a plaque inhibition analysis (data not shown). This implies that it must have infected this host strain before the acquisition of the O139 LPS biosynthesis genes. Several studies indicate that serogroup conversion of O1 into O139 occurred by lateral transfer of the rfb gene cluster between different V. cholerae strains (4), and a comparable process may have taken place for the O141 strain E8498. Moreover, the V1 sequence of classic strain Z17561 differs from that found in classic strain O395 but instead matches that of the non-O1, non-O139 strain Ch457. This finding could lead to two different conclusions. First, the V1 protein domain may not bind to the O-antigen receptor. Since we do not know the rest of the tail fiber sequence from the Z17561 strain, it is possible that the V2 regions determine the host range and are identical. This would also help to explain why the V1 protein domain of the O1 classical strain O395 prophage is different from that of the O1 El Tor phage, i.e., because both phages share the same V2 sequence. Second, if the V1 protein domain is involved in receptor binding, then the tail fibers of the classic strains might not bind to the O1 antigen of their host strains, indicating that perhaps another O antigen was present when the classical V. cholerae strains acquired their prophage.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the presumed tail fiber proteins of the K139-related phages. Similar shading of boxes within the proteins indicates sequence similarity of ≥80%; different shading indicates similarity of ≤42%. The two regions with homology to tail fiber proteins of other phages are indicated by different patterns. The asterisk marks the fragment sequence of V. cholerae classical strain Z17561, which was derived from the database. V1 and V2, variable regions 1 and 2; C1 and C2, conserved regions 1 and 2; aa, amino acids.

Conclusion.

In summary, we determined the complete phage genome sequence and established the putative functions of some of the deduced ORF products by their homology to P2-like gene products. One ORF product, ORF8, can be characterized as a 5′-GATC-3′-specific Dam-methyltransferase. Furthermore, hybridization studies identified related K139 phages within different serogroups of V. cholerae. Most regions of the genomes of K139-like phages are conserved; however, we identified a region of variable gene content, probably acquired by recombinational events. Comparison of the putative tail fiber gene products of these phages revealed the presence of variable domains, which may be involved in host receptor recognition. The results again demonstrate how recombination processes contribute to the evolution of this group of phages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jutta Nesper for her help and valuable contributions to the manuscript. We also thank Andrew Camilli and Stefan Schlör for many helpful comments, critical reading, and suggestions.

This work was funded by BMBF grant 01KI8906 and by the Nachwuchsgruppenförderung, Land Bayern.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, H. W. 2001. Frequency of morphological phage descriptions in the year 2000. Arch. Virol. 146:843-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Albert, M. J., A. K. Siddique, M. S. Islam, A. S. Faruque, M. Ansaruzzaman, S. M. Faruque, and R. B. Sack. 1993. Large outbreak of clinical cholera due to Vibrio cholerae non-O1 in Bangladesh. Lancet 341:704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertani, E. L., and E. W. Six. 1988. The P2-like phages and their parasite, P4, p. 73-143. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages, vol. 2. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bik, E. M., A. E. Bunschoten, R. D. Gouw, and F. R. Mooi. 1995. Genesis of the novel epidemic Vibrio cholerae O139 strain: evidence for horizontal transfer of genes involved in polysaccharide synthesis. EMBO J. 14:209-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjellqvist, B., C. Pasquali, F. Ravier, J. C. Sanchez, and D. Hochstrasser. 1993. A nonlinear wide-range immobilized pH gradient for two-dimensional electrophoresis and its definition in a relevant pH scale. Electrophoresis 14:1357-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bockemühl, J., and A. Triemer. 1974. Ecology and epidemiology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus on the coast of Togo. Bull. W. H. O. 51:353-360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botstein, D. 1980. A theory of modular evolution for bacteriophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 354:484-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casadaban, M. J. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104:541-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chattoraj, D. K. 1978. Strand-specific break near the origin of bacteriophage P2 DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:1685-1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chattoraj, D. K., and R. B. Inman. 1973. Origin and direction of replication of bacteriophage 186 DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70:1768-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark, A. J., W. Inwood, T. Cloutier, and T. S. Dhillon. 2001. Nucleotide sequence of coliphage HK620 and the evolution of lambdoid phages. J. Mol. Biol. 311:657-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz, E., E. Garcia, C. Ascaso, E. Mendez, R. Lopez, and J. L. Garcia. 1989. Subcellular localization of the major pneumococcal autolysin: a peculiar mechanism of secretion in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1238-1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodd, I. B., and J. B. Egan. 1990. Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5019-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan, J. B., and I. B. Dodd. 1994. P2, P4 and related bacteriophages, p. 1003-1009. In R. G. Webster and A. Granoff (ed.), Encyclopedia of virology. Academic Press, London, England.

- 15.Esposito, D., W. P. Fitzmaurice, R. C. Benjamin, S. D. Goodman, A. S. Waldman, and J. J. Scocca. 1996. The complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage HP1 DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2360-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujisawa, H., and M. Morita. 1997. Phage DNA packaging. Genes Cells 2:537-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funnell, B. E., and R. B. Inman. 1983. Bacteriophage P2 DNA replication. Characterization of the requirement of the gene B protein in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 167:311-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerdes, J. C., and W. R. Romig. 1975. Complete and defective bacteriophages of classical Vibrio cholerae: relationship to the Kappa type bacteriophage. J. Virol. 15:1231-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimberg, J., S. Maguire, and L. Belluscio. 1989. A simple method for the preparation of plasmid and chromosomal E. coli DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:8893.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grünenfelder, B., G. Rummel, J. Vohradsky, D. Röder, H. Langen, and U. Jenal. 2001. Proteomic analysis of the bacterial cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4681-4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haggard-Ljungquist, E., C. Halling, and R. Calendar. 1992. DNA sequences of the tail fiber genes of bacteriophage P2: evidence for horizontal transfer of tail fiber genes among unrelated bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 174:1462-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleischmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henrich, B., B. Binishofer, and U. Blasi. 1995. Primary structure and functional analysis of the lysis genes of Lactobacillus gasseri bacteriophage φadh. J. Bacteriol. 177:723-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honma, Y., M. Ikema, C. Toma, M. Ehara, and M. Iwanaga. 1997. Molecular analysis of a filamentous phage (fsl) of Vibrio cholerae O139. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1362:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikema, M., and Y. Honma. 1998. A novel filamentous phage, fs-2, of Vibrio cholerae O139. Microbiology 144:1901-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koonin, E. V., and T. V. Ilyina. 1993. Computer-assisted dissection of rolling circle DNA replication. Biosystems 30:241-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kossykh, V. G., S. L. Schlagman, and S. Hattman. 1995. Phage T4 DNA [N6-adenine]methyltransferase. Overexpression, purification, and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14389-14393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linderoth, N. A., B. Julien, K. E. Flick, R. Calendar, and G. E. Christie. 1994. Molecular cloning and characterization of bacteriophage P2 genes R and S involved in tail completion. Virology 200:347-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, Y., and E. Haggard-Ljungquist. 1994. Studies of bacteriophage P2 DNA replication: localization of the cleavage site of the A protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5204-5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loessner, M. J., S. K. Maier, H. Daubek-Puza, G. Wendlinger, and S. Scherer. 1997. Three Bacillus cereus bacteriophage endolysins are unrelated but reveal high homology to cell wall hydrolases from different bacilli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2845-2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malone, T., R. M. Blumenthal, and X. Cheng. 1995. Structure-guided analysis reveals nine sequence motifs conserved among DNA amino-methyltransferases, and suggests a catalytic mechanism for these enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 253:618-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClelland, M., M. Nelson, and E. Raschke. 1994. Effect of site-specific modification on restriction endonucleases and DNA modification methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3640-3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mekalanos, J. J. 1983. Duplication and amplification of toxin genes in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 35:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Mulligan, M. E., D. K. Hawley, R. Entriken, and W. R. McClure. 1984. E. coli promoter sequences predict in vitro RNA-polymerase selectivity. Nucleic Acid Res. 12:789-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakayama, K., S. Kanaya, M. Ohnishi, Y. Terawaki, and T. Hayashi. 1999. The complete nucleotide sequence of φCTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 31:399-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nesper, J., J. Blass, M. Fountoulakis, and J. Reidl. 1999. Characterization of the major control region of Vibrio cholerae bacteriophage K139: immunity, exclusion, and integration. J. Bacteriol. 181:2902-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nesper, J., D. Kapfhammer, K. E. Klose, H. Merkert, and J. Reidl. 2000. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 antigen as the bacteriophage K139 receptor and identification of IS1004 insertions aborting O1 antigen biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:5097-5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nesper, J., A. Kraiss, S. Schild, J. Blass, K. E. Klose, J. Bockemuhl, and J. Reidl. 2002. Comparative and genetic analysis of the putative Vibrio cholerae lipopolysaccharide core oligosaccharide biosynthesis (wav) gene cluster. Infect. Immun. 70:2419-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odegrip, R., and E. Haggard-Ljungquist. 2001. The two active-site tyrosine residues of the A protein play non-equivalent roles during initiation of rolling circle replication of bacteriophage P2. J. Mol. Biol. 308:147-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piekarowicz, A., and J. Bujnicki. 1999. Cloning of the Dam methyltransferase gene from Haemophilus influenzae bacteriophage HP1. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 48:123-129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portelli, R., I. B. Dodd, Q. Xue, and J. B. Egan. 1998. The late-expressed region of the temperate coliphage 186 genome. Virology 248:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reidl, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae bacteriophage K139 and use of a novel mini-transposon to identify a phage-encoded virulence factor. Mol. Microbiol. 18:685-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose, R. E. 1988. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC184. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:355.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slauch, J. M., M. J. Mahan, P. Michetti, M. R. Neutra, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Acetylation (O-factor 5) affects the structural and immunological properties of Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide O antigen. Infect. Immun. 63:437-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonnhammer, E. L., G. von Heijne, and A. Krogh. 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 6:175-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Southern, E. M. 1975. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 98:503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stormo, G. D., T. D. Schneider, and L. M. Gold. 1982. Characterization of translational initiation sites in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 10:2971-2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tatusova, T. A., and T. L. Madden. 1999. BLAST 2 sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waldor, K. W., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, I. N., D. L. Smith, and R. Young. 2000. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:799-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamamoto, K., Y. Takeda, T. Miwatani, and J. P. Craig. 1983. Purification and some properties of a non-O1 Vibrio cholerae enterotoxin that is identical to cholera enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 39:1128-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]