Abstract

Temperate bacteriophages effect chromosomal evolution of their bacterial hosts, mediating rearrangements and the acquisition of novel genes from other taxa. Although the Haemophilus influenzae genome shows evidence of past phage-mediated lateral transfer, the phages presumed responsible have not been identified. To date, six different H. influenzae phages are known; of these, only the HP1/S2 group, which lyosogenizes exclusively Rd strains (which were originally encapsulated serotype d), is well characterized. Phages in this group are genetically very similar, with a highly conserved set of genes. Because the majority of H. influenzae strains are nonencapsulated (nontypeable), it is important to characterize phages infecting this larger, genetically more diverse group of respiratory pathogens. We have identified and sequenced HP2, a bacteriophage of nontypeable H. influenzae. Although related to the fully sequenced HP1 (and even more so to the partially sequenced S2) and similar in genetic organization, HP2 has a few novel genes and differs in host range; HP2 will not infect or lysogenize Rd strains. Genomic comparisons between HP1/S2 and HP2 suggest recent divergence, with new genes completely replacing old ones at certain loci. Sequence comparisons suggest that H. influenzae phages evolve by recombinational exchange of genes with each other, with cryptic prophages, and with the host chromosome.

The host range of temperate bacteriophages is determined by multiple factors. Since phages require cellular components for replication, they become specialized to a compatible bacterial species. Within a host species, divergent restriction systems and surface receptors create barriers to interstrain transmission. Phages may overcome host range barriers by evolving DNA methylation systems (24) or by varying the structure of tail fiber proteins used for adsorption (31). The temperate bacteriophages of nonencapsulated (e.g., nontypeable) Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) face adaptive challenges because of the unusually high genetic diversity of these bacteria (43). Here we describe a new temperate prophage, HP2, found in NTHI strains that are associated with unusual virulence.

Although six H. influenzae phages are described in the literature (HP1, S2A, B, C, N3, and φflu), only HP1 and three types of S2 have been described in detail (4, 19, 21, 30, 43). Both HP1 and S2 infect H. influenzae Rd strains (4, 19), which were originally derived from an encapsulated serotype d (Sd) strain, but do not possess the genes for capsular biosynthesis (2, 15). We have discovered a new member of the HP1/S2 family that occurs as a prophage in the chromosome of strain R2866, a nontypeable invasive H. influenzae isolate (26).

DNA sequence analysis of HP1 and S2 types A, B, and C shows that these phages are closely related. Closer examination shows that type C is probably the original HP1 (37). Type A has many similarities to type C, but differences in the structures of the early promoter region suggest a different regulation of the lytic-versus-lysogeny decision. The type B variety appears to be a chimera between types A and C. The original host of the HP1/S2 bacteriophages is unknown, but UV-induced mixed-culture filtrates lysogenized an Rd derivative. All HP1 and S2 type phages have similar morphologies when viewed with an electron microscope. The N3 bacteriophage has a similar head structure, but a longer tail. The N3 phage is found only in particular NTHI strains, and on restriction analysis, it has a pattern distinct from HP1 (43). No other information or sequence data on N3 are available. φflu is an incomplete phage found in the Rd KW20 genome and has genes homologous to ones in HP1 (21).

HP1, with its 32-kb genome, belongs to the family of bacteriophages represented by Escherichia coli P2. Historically HP1 was used to elucidate the mechanism of natural transformation in H. influenzae (6, 27, 33, 41, 42). HP1 is a temperate phage capable of either a lytic infection or lysogeny of the host. The promoters controlling the lysis-versus-lysogeny decision are located near the 5′ end of the genome (9): one leftward and two rightward promoters transcribe cI and cox, which have genetic and functional homology to transcriptional regulators in lambda. In vitro HP1 cI, cox, and int function similarly to their counterparts in lambda. In HP1, the majority of the genes downstream from these regulators appear to encode proteins that are part of phage structure and assembly apparatus. The function of these downstream genes is inferred on the basis of homology to genes in other phages.

The S2 phages also appear capable of a temperate life cycle in Rd hosts. The 5′ 5.6 kb of this phage was sequenced for comparison to HP1 (36). Major sequence differences between S2 and HP1 are interspersed with regions of high homology.

While investigating a previously described invasive NTHI strain (26, 46), we found a prophage whose range was limited to this strain and a few other NTHI strains. To elucidate whether the phage provided clues to the unusual virulence of this strain, we sequenced its chromosome and found a close relationship to HP1 and S2. H. influenzae Sd strains and Rd derivatives are not lysogenic for HP2; however, HP2 can lysogenize a phage-deleted form of its original host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and media.

The bacteria used in this study are described in Table 1. Strain R2866, originally described as Int1, is a biotype V, nontypeable H. influenzae strain isolated from the blood of an immunocompetent child with signs of meningitis (26). This strain is serum resistant and harbors a 54-kb conjugal plasmid that encodes a β-lactamase. sBHI broth was made up of brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) supplemented with 10 μg (each) of hemin-HCl (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), l-histidine (Sigma), and β-NAD (Sigma) per ml. The heme solution was prepared by mixing 100 mg of hemin-HCl and l-histidine in 100 ml of 50°C water, to which 0.4 ml of 10 N NaOH (Sigma) is added. The solution was filter sterilized with a 0.22-μm-pore-diameter filter and stored at 4°C in a lightproof container for no more than 3 weeks. β-NAD was dissolved in water to a concentration of 1 mg/ml, filter sterilized, and stored at 4°C. One volume of these solutions was aseptically added to 100 volumes of BHI broth prior to use. Chocolate agar was prepared as described by Difco with GC Media base. To avoid contamination with gram-positive organisms, bacitracin was added to all solid H. influenzae growth media at a final concentration of 500 U/liter (10 μg/ml), and all incubations were done at 37°C in air. Luria-Bertani (LB) agar and broth (Difco) were used for E. coli.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this work

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Cloning host | Gibco BRL |

| H. influenzae | ||

| Rd | Derivative of Garf Sd | 2 |

| Rd KW20 | Genome sequence | 45 |

| R3153 | Rd strain for plaquing (BC200) | 3 |

| Rd Mc1 | Minicell producing strain | 32 |

| R3152 | HP1 lysogen | 6 |

| R2866 | HP2 lysogen | 26 |

| R539 | Type a (Pittman 610) | ATCC 9006 |

| R538 | Type b (Pittman 641) | ATCC 9795 |

| R540 | Type c (Pittman 624) | ATCC 9007 |

| R541 | Type d (Pittman 611) | ATCC 9008 |

| R542 | Type e (Pittman 595) | ATCC 8142 |

| R543 | Type f (Pittman 644) | ATCC 9833 |

| Other Haemophilus sp. strains | ||

| H. somnus | ATCC 43625 | |

| R1966 | H. parainfluenzae | ATCC 33392 |

| R3358 | H. aegyptius | ATCC 11116 |

| R1968 | H. aphrophilus | ATCC 33389 |

| R1969 | H. paraphrophilus | ATCC 29241 |

| R1970 | H. haemolyticus | ATCC 33390 |

| R1985 | H. parahaemolyticus | ATCC 29237 |

| R1972 | H. haemoglobinophilus | ATCC 19416 |

| R1973 | H. segnis | ATCC 33393 |

| R1974 | H. parasuis | ATCC 19417 |

| R1976 | H. equigenitalis | ATCC 35865 |

| R1985 | H. parahaemolyticus | ATCC 10014 |

| R1986 | H. paracuniculus | ATCC 29986 |

| R1989 | H. paragallinarum | ATCC 29545 |

| R1990 | H. avium | ATCC 29546 |

| R1992 | H. ducreyi | ATCC 33940 |

| R1975 | H. pleuropneumoniae | ATCC 27088 |

| Other gram-negative spp. | ||

| N. gonorrhoeae | Joan Knapp, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. | |

| P. multocida | ATCC 8369 | |

| P. aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | |

| H. influenzae strain constructs | ||

| R3420 | R2866 with HP2 deleted, Ribr | This study |

| R3422 | R2866 with HP2 deleted, Cmr | This study |

| R3403 | R3152 with first 5 kb of HP2 (HP1/HP2P) | This study |

| R3404 | R2866 with first 5 kb of HP1 (HP2/HP1P) | This study |

| R3435 | R2866 with TSTE insertion in HP2 dam, Ribr | This study |

Phage induction.

To induce bacteriophage from the lysogens, a 100-ml sBHI culture was grown with shaking at 1,200 rpm at 37°C to an A600 of 0.15 to 0.2. Mitomycin C (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 35 ng/ml, and the culture was shaken at 50 to 100 rpm. Bacterial replication continued to an A600 of 1.0, after which the optical density decreased, presumably due to phage-mediated lysis. When the optical density reached its minimum, generally 4 to 6 h after the addition of mitomycin C, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C in a Beckman J21 centrifuge. The supernatant was removed, and the centrifugation step was repeated to remove residual intact cells. The resulting supernatant was passed through a 0.22-μm-pore-diameter filter, after which chloroform was added (20 μl/100 ml). Phage-containing supernatant was stored at 4°C until further use. To concentrate the bacteriophage particles, the supernatant was centrifuged in 33-ml ultracentrifuge tubes at 40,000 rpm in a Ti 50.2 rotor for 3 h at 15°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a minimal amount of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking.

Plaque assay.

Bacteria were grown in sBHI broth to an A600 of 0.2 and then mixed with 1:5 to 1:100,000 dilutions (in PBS) of culture supernatant prepared as described above for phage induction. Soft agar consisted of 5 ml of 0.7% sBHI agar layered on a standard sBHI agar plate. The target strain was grown in sBHI broth to an A600 of 0.2 and diluted 1:100 in the same medium, an aliquot was added to the phage preparation, and 0.1 ml was spread over the surface of the soft agar. After overnight incubation at 37°C, clear plaques were counted (44).

Electron microscopy.

Concentrated bacteriophage stocks were stained in uranyl acetate (5) and visualized by T.P. with a JEOL 1200 EX transmission electron microscope at the Electron Microscopy Core at the University of Missouri—Columbia.

DNA isolation.

To purify phage for sequencing, 200 μl of resuspended phage pellet in sBHI was treated with 0.1 U of DNase I (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.) for 30 min at 37°C. After DNase treatment, the phage preparation was extracted with an equal volume of Tris-saturated phenol (pH 8.0)-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol in proportions of 25:24:1. The aqueous layer was removed, and the extraction was repeated with an equal volume of fresh phenol solution. The DNA was precipitated from the aqueous layer by addition of 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0) and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol at −20°C and concentrated by centrifugation, and the pellet was washed with 1 ml of 70% ethanol at room temperature. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the ethanol solution was aspirated, and the pellet was allowed to air dry before resuspension in 50 μl of water or PBS.

Sequencing.

Sequencing was performed at the University of Washington Genome Center as described by Stover et al. (40). Phage DNA was cloned into pUC19, and the insert was sequenced with primers synthesized by that unit. The data set involved 462 dye-terminator and 123 dye-primer sequencing reads, sampled at random from the phage genome. The average number of q20 bases per read was 408. A q20 base is a base call with an estimated error rate of 1% as calculated by the PHRED base-calling software (11, 12). The redundancy of the data, in terms of q20 bases, was 7.6. Low-quality regions were resolved by a combination of manual and automated finishing procedures as described previously (17). An estimate of the number of remaining errors in the sequence based on quality scores was calculated with the phrap assembly software (16), which can be accessed at http://www.phrap.org. The expected number of residual errors in this 31.5-kb sequence was 0.16. In our experience, sequence with less than one predicted error usually has no errors. In addition, both strands of the first 10 kb of HP2 from attP to orf10 were independently sequenced at the University of Missouri DNA Core by using the same vector and method, and no differences were observed.

DNA analysis.

Open reading frames (ORFs) were identified using the ORF finder function in the OMIGA software program (Oxford Molecular). The ribosome binding sites in the HP2 ORFs were compared to the previously determined HP1 and S2 sequences to verify the most likely start codons. Similarity plots were obtained with the GCG software program available (Wisconsin Genome Center).

H. influenzae transformation.

H. influenzae was transformed by the M-IV technique (39). Gel-purified PCR fragments or linearized plasmid DNA was added to competent H. influenzae, and dilutions were plated on chocolate agar plates containing either ribostamycin (Sigma) at 30 μg/ml (for the TSTE cassette) or chloramphenicol at 5 μg/ml (for the cat cassette).

Southern analysis.

DNA was transferred from agarose gels to nylon membranes (Osmonics, Inc., Minnetonka, Minn.) by using a vacuum-assisted apparatus (Hoeffer Scientific). Agarose gels were depurinated in 0.25 M HCl for 1 h, followed by denaturation in 1.5 M NaCl containing 0.5 M NaOH for 30 min (29). Transfers were performed for ≥3 h in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), after which the membrane was treated with UV light to cross-link the DNA. Chemiluminescent detection was performed with which digoxigenin-labeled oligonucleotide probes or double-stranded PCR products as recommended by the manufacturers (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.).

PCR amplification.

Table 2 lists the primers used for PCR amplification of selected portions of the HP1 and HP2 prophages. The locations of these primers on the HP2 genome map are shown in Fig. 1. For PCR amplification of fragments shorter than 2 kb, standard Taq polymerase was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.). An Eppendorf thermocycler (model, Mastercycler) was set to run 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s in that order. Occasional primer sets required adjustment of the annealing temperature. For larger products of up to 18 kb, the long-range PCR kit from Roche (GeneAmp XL) was used.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Primer | Sequencea | Target/use |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAGACGGATCCGTTTGCACAACTACGGGCTTA | Cloning of the 5′ terminus of HP2 upstream of attP (BamHI) |

| 2 | GAGACCGCTCGAGCGGATGGCTTGCGGAAGTTTATG | Cloning of the 5′ terminus of HP2 upstream of integrase (XhoI) |

| 3 | GAGAGGAAGATCTCCCGGTCAAAATCTACCCGAAA | 3′ terminus of HP2 (BglII) |

| 4 | GAGACGGAATTCCGCTTTAGTTTGCTCCGCAACC | Cloning of the 3′ terminus of HP2 at position 29,742 (EcoRI) |

| 5 | GCTGCTCTACCGACTGAGCTA | Creation of a PCR probe to the early genes of HP1 + HP2 |

| 6 | AGACGGTGAGGCACGTTTAG | Creation of a PCR probe to the early genes of HP1 + HP2 |

| 7 | AAGGGGGAAATAATGGCAAC | Cloning of HP2 genes in the pR promoter group |

| 8 | AAAGGATTGTTATTGCCCC | Cloning of HP2 genes in the pR promoter group |

Sequences run 5′ to 3′, with restriction sites listed in target use underlined.

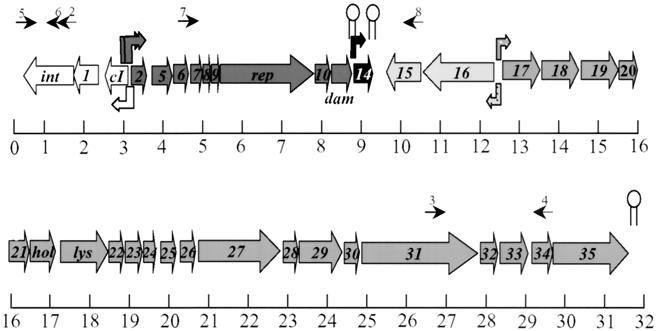

FIG. 1.

Genetic map of HP2. Straight arrows indicate the approximate position of each ORF. The scale is in kilobases. Bent arrows indicate the locations of RNA polymerase promoter elements. Ball-and-stick figures indicate the locations of transcription terminators. Arrows above the map indicate locations of primers used in this work. The length of the HP2 chromosome is 31,508 bp. Primer 1 is homologous to coordinates 3088 to 3072 of the H. influenzae Rd KW20 genome (section 9 of 163).

Construction of an HP2 host.

The plasmids used in the HP2 host construct are described in Table 3. Using PCR primers 1 and 2, a 1.7-kb fragment of HP2 DNA containing int and attP was amplified and ligated to pTrcHisB restricted with BamHI and XhoI (pBJ102). PCR primers 3 and 4 were used to amplify a 2.0-kb downstream portion of the HP2 prophage that was subsequently ligated into pBJ102 digested with BglII and EcoRI (pBJ102.2). A BamHI-restricted TSTE cassette was ligated into BglII-digested pBJ102.2 to create pBJ102.3. The TSTE cassette contains the aph(3′)I gene flanked by H. influenzae-specific uptake (hUS) sequences (34). The TSTE cassette confers ribostamycin resistance to H. influenzae and kanamycin resistance to E. coli. Plasmid pBJ102.3 was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and used to transform competent H. influenzae strain R2866 with selection for ribostamycin resistance. Of 12 ribostamycin-resistant transformants, 2 were shown to be devoid of most of the prophage genome by Southern blotting and to lack phage production after mitomycin C treatment, as assessed by electron microscope observation and infection assays (data not shown). One such mutant was designated R3420 (Fig. 2). R3422 is a derivative of R3420 with a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase cassette replacing the aph(3′)I gene, inserted between two HincII sites.

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pKS | Cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pUC18 | Cloning vector | 47 |

| pTrcHisB | Vector for production of His-tagged fusion | Invitrogen |

| pUC4DEcat | cat gene used in H. influenzae cloning Chlorr | 7 |

| pTSTE | apH(3′)I flanked by H. influenzae uptake sequences in pBR322; Ribr | 34 |

| pBJ100.1 | HindIII fragment of R2866 chromosome from position 139332 (in HI0123) to bp 5194 of the prophage in pUC18 | This study |

| pBJ100.2 | pBJ100.1 with TSTE located in BamHI site upstream of the prophage attP site | This study |

| pBJ102 | TrcHisB containing a 1.7-kb fragment from the 5′ end of the HP2 prophage | This study |

| pBJ102.2 | pPBJ102 containing a 2.0-kb fragment of the 3′ end of the HP2 prophage 3′ to the early fragment | This study |

| pBJ102.3 | apH(3′)I inserted between the two prophage fragments in pBJ102.2 | This study |

| pBJ102.4 | dCAT inserted between the two prophage fragments in pBJ102.1 | This study |

| pBJ105 | pKS containing the HindIII-EcoRI fragment of the HP2 prophage located in the pR transcription frame | This study |

| pBJ105.2 | pBJ105 with TSTE located in the NcoI site in dam | This study |

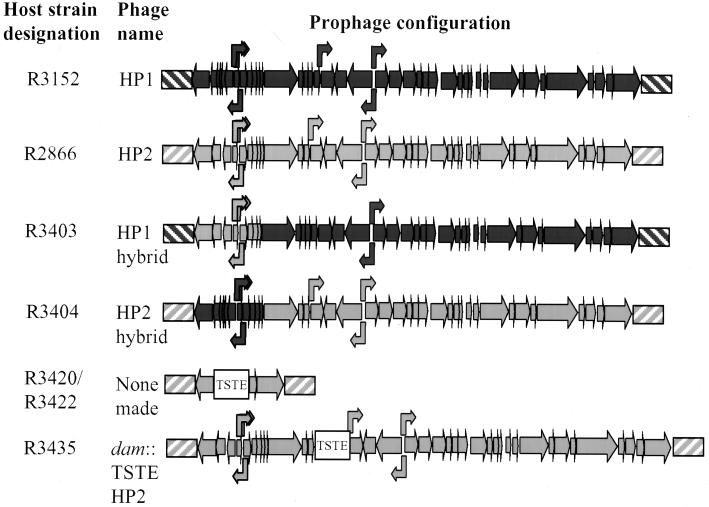

FIG. 2.

Genetic maps of strains used in this work. Straight arrows indicate ORFs and their orientation. Bent arrows indicate the locations of the transcription promoters. Diagonal striped boxes indicate the boundaries of host DNA. DNA originating from the HP1 or HP2 host is shown in dark or light gray, respectively. The TSTE box indicates the location of the antibiotic cassette used for genetic manipulations. These maps are not to scale but approximate the total numbers of genes and their relative sizes.

Construction of hybrid lysogens.

Early experiments indicated that HP2 would not form plaques on any of the Rd derivatives or strain R3420, its original host, from which HP2 was isolated. To identify the genetic regions determining the host range of HP2, we created hybrid lysogens of HP1 and HP2 (Fig. 2). This was accomplished by first cloning a 7.5-kb HindIII prophage fragment containing the HP2 immunity genes from strain R2866 into the HindIII site of pUC18. This plasmid, designated pBJ100.1, contains a portion of a threonine synthetase gene and a BamHI site in an intergenic region 5′ to the prophage. After cloning TSTE into this BamHI site, the plasmid (pBJ100.2) was linearized and transformed into competent R3152 selecting for ribostamycin resistance. One transformant (designated HP1/HP2P [strain R3403]) of 12 examined acquired the HP2 immunity region as indicated by PCR. The chromosomal DNA of another transformant that retained the HP1 immunity region was digested and transformed into R2866. One transformant of the 12 that acquired HP1 immunity region was designated HP2/HP1P (strain R3404) (Table 1). To verify the construction of the hybrid phages, we performed a Southern analysis of BglI-restricted DNA harvested from phage preparations of HP1, HP2, HP1/HP2P (R3403), and HP2/HP1P (R3404) by using a digoxigenin-labeled PCR product generated from primers 5 and 6 as a probe. HP2 contains a 2.0-kb fragment, while in HP1, the hybridizing fragment is smaller, as predicted. HP1/HP2P has the 2-kb BglI fragment, while HP2/HP1P has the smaller fragment.

Construction of marked HP2 derivative.

To assess the ability of HP2 to lysogenize a host, we created a prophage mutant in R2866 with the TSTE cassette marking the phage. The insertion of TSTE into the phage dam gene resulted in no detectable phenotypic changes in growth rate or phage yields. This insertion was created by first cloning a portion of the prophage with primers 7 and 8 to amplify a 7-kb segment of the phage containing most of the genes driven by the pR promoters. This PCR product was digested with HindIII and EcoRI and ligated into pKS to create pBJ105. pBJ105 was digested with NcoI, which cuts this plasmid uniquely in the dam gene, and was treated with T4 polymerase. A BamHI-digested, T4 polymerase-treated TSTE cassette was ligated to this plasmid to yield pBJ105.2. This plasmid was digested with HindIII and EcoRI and transformed into R2866 with subsequent selection of ribostamycin-resistant colonies. Southern analysis of chromosomal DNA and phage extract DNA from eight colonies revealed one mutant, R3435, which contained the TSTE cassette in the dam gene of the HP2 prophage (data not shown).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The HP2 sequence has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AY027935.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The HP2 genome.

The HP2 chromosome consists of 31,508 bp, similar to the size of S2 phage types A and B based on restriction mapping (28). The molar percentage of adenine and thymidine (A+T%) in the HP2 chromosome is 60.04%, a value similar to that in the Rd KW20 chromosome (61.86%) (15). The frequency of the triplet base combinations, coding and noncoding, in HP2 is also very similar to that in Rd KW20 (data not shown), which suggests that this bacteriophage was not recently introduced into H. influenzae.

The organization of the HP2 genome is shown in Fig. 1; cohesive ends are similar to those in HP1 (data not shown). HP2 appears to contain five transcriptional units, with the control of each of these units directing or repressing bacteriophage replication. As in HP1, the pR1, pR2, and pL1 promoters of HP2 adjoin the early regulatory elements. Flanking these promoters are elements believed to control the lysis-versus-lysogeny decision (13). If the products of the pL1 promoter dominate, lysogeny is maintained, repressing all other bacteriophage gene expression. If the pR1 and pR2 promoters are activated, the lytic cycle will ensue. Products of the pR1- and pR2-activated transcript should control bacteriophage DNA replication and presumably activation of the downstream genes through hypothetical promoter elements between orf16 and orf17. Genes responsible for bacteriophage particle production and host lysis reside in these diverging transcripts, one of which contains orf15 and orf16, while the other contains orf17 through orf35. Many of the ORFs in the latter transcript show homology to structural proteins of P2 and other phages. As in HP1, orf14 appears to have its own promoter and terminator. The role of this gene in HP1 and HP2 is unknown. It is unique in being the only gene in these phages that appears capable of independent control.

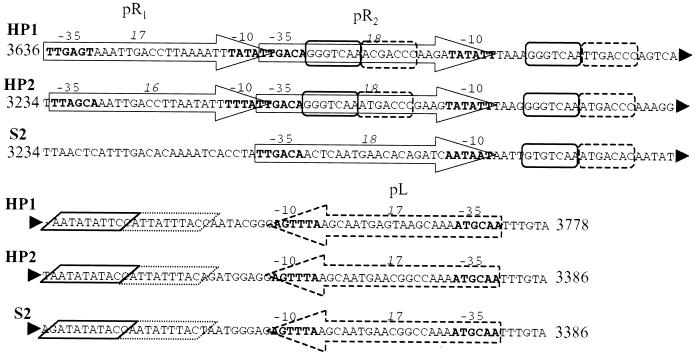

HP2 regulatory elements.

The pR and pL promoters controlling the lysis-versus-lysogeny decision differ among HP1, HP2, and S2 phages. Analysis of these regions indicates that both of the pR promoters are maintained in HP2, whereas the pR1 promoter, and its corresponding cI-coded protein binding site, is missing from S2 (Fig. 3). The nucleotide sequences of these promoter regions differ at numerous sites: areas that are conserved are the −10, −35, and cI- and cox-coded protein binding sites. This suggests HP2 has retained a functional control unit for phage induction and repression. As in S2, the cox homologue of HP1 is absent. Whereas the orf2 genes of HP2 and S2 are similar to cox (see below), the finding of intact Cox protein binding sites suggests that a Cox-like protein performs this function. The spacing between the −10 and −35 sites of pR1 in HP2 is 16 or 17 bp, depending on which thymidine residue is considered the start of the −10 site. The pR1 promoter may be functionally redundant, since S2 lacks pR1, yet appears fully capable of controlling lysis versus lysogeny in H. influenzae Rd strains.

FIG. 3.

Early promoter comparison among HP1, HP2, and S2 type A. The numbers on either side of the sequences denote the nucleotide positions of these loci in their respective phages. Large arrows delineate the promoter elements with the −35 and −10 sites in boldface and labeled. Italic numbers denote the spacing between the −35 and −10 sites. Dashed lines indicate elements contained on the opposite strand. Rounded boxes identify sequences consistent with the cI repressor binding sites, and the parallelograms indicate the cox repressor binding sites.

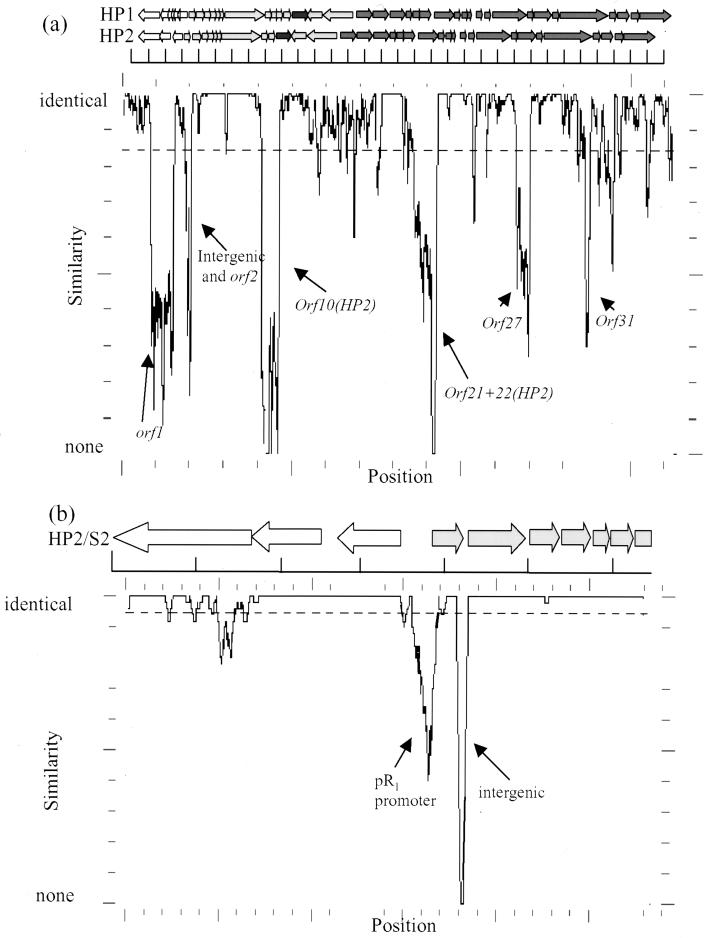

Outside of this promoter region, the sequence of HP2 is very similar to that of S2, while within the promoter region, HP2 is more homologous to HP1 (Fig. 4). All three phages have identical sequences at the −10 and −35 sites of pL, the leftward promoter, and the sequence between these promoters, suggesting a close relationship between S2 and HP2. It seems unlikely that HP2 is a simple recombinant of S2 and HP1, because certain regions in each phage have a different nucleotide sequence.

FIG. 4.

Sequence comparison of HP2 to HP1 and S2 type A. Similarity plots are measured as percent difference from the designated window size. The dashed line represents the overall average similarity. Large peaks demonstrate the largest differences that are labeled with the HP2 gene or region showing this difference. The scale under the genetic maps is in kilobases. (a) Complete chromosome comparison between HP1 and HP2. Genetic maps are aligned to show differences in gene arrangement. A similarity plot scores the similarity over a 100-bp window. (b) Comparison of the first 5.6 kb of S2 type A with HP2. The genetic maps of HP2 and S2 are identical in this region. This similarity plot was calculated over a 50-bp window.

Regulation of lysis.

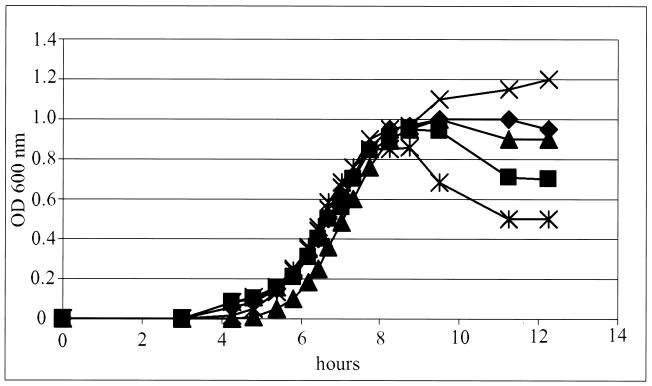

Since the structures of the promoter elements and repressors controlling the lysis-versus-lysogeny decision differ between HP1 and HP2 (see above), we sought to determine if the HP2 immunity region could mediate mitomycin C induction in an Rd host. We generated a hybrid phage in which the first 5 kb of HP2 from attP to orf7 was replaced with the homologous region of HP1 (HP2/HP1P [strain R3404]). Conversely, we constructed an HP1 lysogen in which the first 5 kb was replaced with the homologous region of HP2 (HP1/HP2P [strain R3403]). After mitomycin C induction, the A600 of the R3403 culture decreased in a manner similar to that of strain R3152 (Fig. 5). This indicates that the promoter region of HP2 is compatible with mitomycin induction and is capable of inducing phage replication and lysis in an H. influenzae Rd derivative. Strain R3404 grew only on solid media, precluding examination of the effect of mitomycin C.

FIG. 5.

Change in A600 (OD 600) after addition of mitomycin C. Mitomycin C was added when the culture reached an A600 of 0.15. ▴, R2866; ♦, R3422; ▪, R3152; X, Rd; *, R3403.

Plaque formation.

Strain R3152 typically yielded between 3.6 × 104 and 4.2 × 105 PFU/ml of culture supernatant with mitomycin C induction when it formed plaques on strain BC200. Similar titers were obtained when HP1 formed plaques on strains Rd and Rd Mc1. We did not observe HP1 plaques with any of the encapsulated H. influenzae strains, any of the other Haemophilus species, or Pasteurella multocida, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Similarly HP2 would not form plaques on any Haemophilus species listed in Table 1 or on P. multocida, N. gonorrhoeae, or P. aeruginosa.

At high phage concentrations, both HP1 and HP2 completely cleared lawns of strains Rd and R3422, respectively (Table 4). Plaques on a lawn of Rd became visible when HP1 was diluted 10,000-fold. The plaques produced by HP1 ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 mm in size and were usually turbid. Gradual dilution and infection of R3422 with HP2 resulted in lawns that gradually became more turbid as the phage concentration was decreased, but plaques were never observed. HP1 would not produce plaques in strain R3422. Thus, HP2 is restricted to its original host, while HP1 will only infect Rd derivatives. Lysogens of either phage, as well as the hybrid lysogens, were immune to infection by their own phage. Furthermore, the hybrid phage induced from strain R3403 had the same host range, even though it contained the HP2 early promoter region and immunity genes. Thus, the differences in plaquing between HP1 and HP2 do not lie within the early control region. It is possible that R2866 and its derivative, R3422, are inherently resistant to lysis, including plaquing. Preliminary experiments indicate that R2866 is more resistant to polymyxin-induced lysis than strain Rd KW20 (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Plaquing assays with HP1, HP2 and mutant phagesa

| Strain produc- ing phage | Phage pretreatment | Strain to be plaqued | Plaquing strain pretreatment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2866 (HP2) | R2866 | Turbid lawn | ||

| R2866/R3404 | R3422 | Complete lysis, no growth | ||

| R2866/R3404 | Diluted 1:100 | R3422 | Uniform incomplete lysis | |

| R2866/R3404 | Diluted 1:10,000 | R3422 | Turbid lawn | |

| R2866/R3404 | Rd | Turbid lawn | ||

| R3152 (HP1) | R3152 | Turbid lawn | ||

| R3152/R3403 | Rd | Complete lysis, no growth | ||

| R3152/R3403 | Diluted 1:100 | Rd | Uniform incomplete lysis | |

| R3152/R3403 | Diluted 1:10,000 | Rd | 1,000 plaques | |

| R3152/R3403 | R2866 | Turbid lawn | ||

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000, absorbed to Rd | Rd | Turbid lawn | |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000, absorbed to R3422 | Rd | Turbid lawn | |

| R2866 | Absorbed to Rd | R3422 | Uniform incomplete lysis | |

| R3152 | Rd | Preincubated with HP2 | Turbid lawn | |

| R2866 | R3422 | Preincubated with HP1 | Turbid lawn | |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000 | Rd | Preincubated with HP2 | Turbid lawn |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000 | Rd | Preincubated with dam::TSTE HP2 | Turbid lawn without antibiotic selection, no growth with ribostamycin |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000 | Rd | Preincubated with HP2 diluted 1:100 | 1,000 turbid plaques |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000 | Rd | Preincubated with HP2 diluted 1:10,000 | 1,000 plaques |

| R3152 | Diluted 1:10,000, absorbed to HP2 preabsorbed Rd culture | Rd | Turbid lawn | |

| R2866 | Absorbed to HP1 preabsorbed R3422 culture | R3422 | Turbid lawn |

The first column describes the host of the phage used in the plaquing assay. When more than one strain is listed, phages from either strain gave the same result. The second column describes any treatment the phage received prior to exposing it to the strain to be plaqued against in column 3. The fourth column describes any treatment the strain to be plaqued received prior to exposure with the test phage in column 1.

Evidence for lysogenic conversion by HP2.

While HP2 appears to infect the prophage-deleted mutant R3422, it was not clear if it could lysogenize infections. To determine whether HP2 was capable of lysogenic conversion of the strain with the phage deleted, strain R3435 (the TSTE antibiotic cassette located in the dam gene of the HP2 prophage) was created. The dam gene encodes an adenine methylase that does not appear necessary for growth, because this mutant prophage is still methylated by the host's methylase (data not shown). Phage induced from R3435 was mixed with strains Rd, R3422, and R2866 (Table 1) and plated on ribostamycin-containing chocolate agar. One hundred microliters of this supernatant contained ∼16,000 ribostamycin-conferring units when monitored with strain R3422. Treatment of strain Rd with R3435 phage did not generate any ribostamycin-resistant colonies; however, treatment of strain R2866 generated ∼160 ribostamycin-resistant colonies. The same phenomenon similarly occurred when marked HP1 or HP2 was mixed with ribostamycin-susceptible lysogens. When the phage preparation was treated with DNase, ribostamycin-resistant transformants were not obtained, indicating that transformation was the most likely mechanism of gene transfer. Transfer of ribostamycin resistance via phage from R3435 to R3422 was relatively DNase resistant compared to transfer to an HP2 lysogen. Furthermore, the transfer efficiency from R3435 was approximately 100-fold higher with transfer into strain R3422, which does not have large regions of homology for the phage recombination. This suggests that HP2 is capable of lysogeny in addition to lysis in strain R3422.

We would suspect phage infection to be much more efficient than transformation. However, we have observed high transformation rates (up to 104 CFU/μg of DNA) with TSTE-marked homologous DNA fragments into strain R2866. Scocca has reported that the HP1 phage is extremely fragile (personal communication), and we suspect this contributes to a large amount of unpackaged phage DNA in these preparations that is available for transformation.

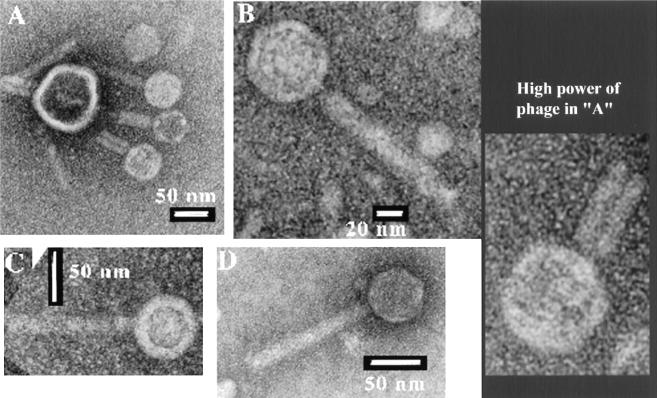

Electron microscopy studies.

Using a concentrated HP2 solution, we used electron microscopy to determine the morphology of HP2 (Fig. 6). As predicted from the sequence similarities, HP2 is identical to HP1 by all visible measures. Its head measures 50 ± 4.5 nm in diameter, while its tails are 110 ± 10 nm, which is approximately the size of the HP1 and S2 phages (5). Some sheaths are found contracted, suggesting that an injection mechanism is likely responsible for transferring the phage chromosome into the bacterial host.

FIG. 6.

HP2 phage particle structure.

Promoter elements for structural genes.

As in HP1, the genes controlling structural elements appear to lack a sigma 70-like promoter, and very few intergenic regions exist in these downstream genes. Of the intergenic regions, only the one between orf16 and orf17 shows potential for a likely promoter element. orf16 and orf15 are oriented oppositely from the genes starting at orf17, and thus a pair of oppositely oriented promoters is consistent with this organization. There is an inverted repeat between orf15 and orf16 (Fig. 7), suggesting that one regulator could bind both regions and drive both transcripts equally. Presumably this regulator exists somewhere 3′ to the orf2/cox gene in the pR-driven transcript. Conservation of regulatory elements and long transcripts is a common theme in bacteriophages (1).

FIG. 7.

orf31 amino acid sequence comparison. The amino acid sequences of orf31 of HP2 and HP1 are aligned as labeled. The middle line depicts the similarity of the sequences from lines 1 and 3. Gray-shaded boxes show regions with high homology.

In HP2, the promoter controlling expression of orf14 is identical to the one in HP1. In fact, orf14 shows 100% identity at the protein level between the two phages. As in HP1, there do not appear to be any cox- or cI-coded protein binding sites near the orf14 promoter presumably putting it under control of an alternative regulator: orf14 may be capable of transcription, independent of the usual phage regulators.

Comparison to HP1 and S2.

The HP2 phage appears to be closely related to the HP1 phage (Fig. 4a). Its chromosome is 31.5 kb (1 kb smaller than that of HP1), and it does not contain as many ORFs as HP1: 36 in HP2 compared to 41 in HP1. Of the 41 HP1 ORFs, 35 are hypothetical based on the ORF encoding a protein of >7 kDa and the presence of a potential ribosomal binding site (9). According to the same criteria, the HP2 chromosome contains 36 ORFs. The organization of the first four ORFs suggests that HP2 is very closely related to the S2 type A phage (Fig. 4b). As in S2, orf2, orf3, and orf4 of HP1 are missing in HP2: orf11 and orf12 of HP1 are also missing from HP2. All of these small genes were contained in the early regulatory region. The downstream sequence, believed to contain the genes encoding phage structural elements, appears to be highly conserved. The promoters and terminators of the downstream transcripts are identical, as is the number of genes compared to HP1. This mosaic pattern is typical when comparing closely related phages and suggests that divergence occurs by recombination with each other, host DNA, and probably cryptic phages such as φflu (25, 31, 36).

One area of the chromosome is unique to HP2: a small portion of noncoding DNA, labeled as “intergenic” in Fig. 4a and b. This 37-bp sequence is 92% identical to the DNA encoding a portion of the gs60 antigen of Pasteurella haemolytica (A. Mellors and R. C. Lo, unpublished observations [GenBank accession no. U42028]). While this DNA does not code for a product, it does suggest a possible lateral genetic exchange. Lateral DNA transfer occurs from H. influenzae to N. gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis (8, 23), and it seems likely to occur between closely related genera like Haemophilus and Pasteurella.

Restriction map of HP1, HP2, and S2.

While the complete sequence of the S2 phage is unknown, a restriction map of S2 types A, B, and C has been reported (28). Since the first 5.6 kb of each of the S2 and HP2 sequences shows a great deal of homology, it might be concluded that they are the same phage in different hosts. A comparison of the limited restriction map of HP1 and the S2 phages with that of HP2 is shown in Table 5: HP2 has a number of differences in comparison to HP1 and to the three S2 subtypes. Since the restriction map of HP2 was based on sequence and that of S2 was based on restriction digests, some differences may be artifactual. Secondary structure may also conceal some restriction sites, and host modification of the phage DNA may account for some differences, because the restriction systems in R3152 and R2866 are likely different.

TABLE 5.

Restriction fragment sizes from the HP1/S2 family of bacteriophages

| Restriction fragment | Fragment size (kb) ina:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP1 | HP2 | S2A | S2B | S2C | |

| BamHI | 26.3 | 31.5 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 26.3 |

| 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 6.1 | ||

| BglI | 17.6 | 17.9 | 10.1 | 17.6 | 17.6 |

| 6.2 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 4.8 | 6.1 | |

| 5.0 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 4.8 | |

| 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.35 | |

| 0.89 | 0.94 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.85 | |

| 0.28 | 0.28 | 2.4 | 0.85 | 0.35 | |

| 0.85 | 0.35 | ||||

| 0.35 | |||||

| BglII | 10.5 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.8 |

| 9.6 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | |

| 6.9 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 7.1 | |

| 5.2 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| EcoRI | 17.8 | 12.9 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 17.8 |

| 12.9 | 10.5 | 12.7 | 12.2 | 12.9 | |

| 1.6 | 8.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 | ||

| HaeIII | 6.7 | 8.3 | 6.75 | 6.75 | 6.75 |

| 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.6 | |

| 3.9 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.75 | |

| 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.45 | 2.45 | |

| 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 2.45 | 2.45 | |

| 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.35 | |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| 1.0 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 0.97 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.95 | |

| 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.90 | 0.9 | |

| 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||

| 0.05 | |||||

| MspI | 19.0 | 14.7 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 32.4 |

| 13.4 | 11.3 | 2.45 | 2.45 | ||

| 2.29 | |||||

| 0.40 | |||||

| 0.34 | |||||

The fragment sizes of HP1 and HP2 were calculated with sites determined by sequence rather than actual restriction cuts. We have verified the locations of the BamHI, BglII, and EcoRI sites in HP2 (data not shown).

Protein differences between HP1 and HP2.

Table 6 compares the levels of homology of the predicted protein products between HP1 and HP2. The names of the ORFs of the H. influenzae bacteriophages were derived from the original HP1 designation by Esposito et al. (9). When the first 5.6 kb of the S2 phage was sequenced, the ORFs were assigned numbers that matched the HP1 designation, although they were not consecutive. While most of the proteins show a large degree of similarity, there are several striking differences: the orf10(HP2), orf21(HP2) and orf22(HP2) proteins are encoded by genes with no homology with any known DNA sequence in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. While there are differences in sequence, the amino acid similarity scores of these proteins in HP1 in comparison to HP2 suggest conservation of function.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of the HP2 ORFs to those of HP1 and S2

| Genea | Positionb

|

Protein identity/similarityc | Predicted function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP2 | HP1 | |||

| Integrase | 702-1712 | 698-1711 | 97/97, 98/98 | Integrates phage into host chromosome to establish lysogeny |

| orf1(S) | 1715-2476 | 1698-2315 | 0/0, 100/100 | ? |

| cI | 2671-3243 | 3061-3636 | 96/97, 95/97 | Maintains lysogeny by repressing pR promoters |

| orf2(S) cox | 3311-3571 | 3574-3993 | 39/59, 100/100 | Inhibits action of cI and competes with integrase (acts as excisionase) |

| orf5 | 3710-4210 | 4050-4553 | 93/94, 100/100 | ? |

| orf6 | 4232-4597 | 4572-4940 | 98/98, 99/99 | ? |

| orf7 | 4600-4782 | 4940-5125 | 100/100, 100/100 | ? |

| orf8 | 4797-5075 | 5137-5418 | 100/100, 100/100 | ? |

| orf9 | 5129-5386 | 5469-5729 | 100/100, 100/100 | ? |

| rep | 5338-7716 | 5732-8059 | 98/98 | Phage DNA polymerase |

| orf10(HP2) | 7731-8031 | 8071-8370 | 37/61 | ? |

| dam | 8052-8567 | 9169-9687 | 98/98 | Dam methylase |

| orf14 | 8871-9269 | 9989-10390 | 100/100 | ? |

| orf15 | 96411-10675 | 10575-11794 | 97/98 | Portal |

| orf16 | 10668-12488 | 11784-13607 | 96/97 | Terminase |

| orf17 | 12692-13582 | 13826-14722 | 91/93 | Scaffold |

| orf18 | 13588-14595 | 14726-15736 | 96/97 | Capsid |

| orf19 | 14618-15454 | 15750-16595 | 96/97 | Packaging |

| orf20 | 15450-15899 | 16588-17040 | 90/94 | Packaging |

| orf21(HP2) | 15890-16372 | 17028-17528 | 67/79 | ? |

| orf22(HP2) | 16323-17057 | 17506-18189 | 42/61 | ? |

| orf23 | 17332-18459 | 18204-19334 | 99/99 | Tail sheath |

| orf24 | 18489-18915 | 19338-19790 | 100/100 | Tail tube |

| hol | 18987-19238 | 19877-20113 | 98/98 | Holin |

| lys | 19255-19791 | 20106-20666 | 95/96 | Lysis |

| orf25 | 19799-20123 | 20651-20998 | 98/99 | ? |

| orf26 | 20319-20624 | 21185-21493 | 100/100 | ? |

| orf27 | 20816-22942 | 21682-23751 | 73/81 | ? |

| orf28 | 22949-23281 | 23755-24090 | 98/99 | ? |

| orf29 | 23398-24443 | 24083-25264 | 98/99 | ? |

| orf30 | 24456-24980 | 25261-25785 | 100/100 | ? |

| orf31 | 25007-27736 | 25815-28592 | 78/86 | Tail fibers |

| orf32 | 27751-28380 | 28604-29206 | 91/96 | Tail collar |

| orf33 | 28396-29160 | 29239-30015 | 97/98 | ? |

| orf34 | 29150-29707 | 30002-30565 | 94/96 | ? |

| orf35 | 29711-31309 | 30562-32163 | 96/98 | ? |

ORFs with names not beginning in “orf” have experimental functions. Gene names that include “(S)” designate a gene novel to S2 which is also found in HP2. Gene names that include “(HP2)” designate a gene novel to HP2 and that has not been described in either HP1 or S2.

The position numbers refer to the nucleotides composing the start-to-stop codons beginning with the first nucleotide of the phage chromosome as it is packaged in the bacteriophage head.

Identity/similarity scores refer to the score of amino acid identity or similarity of the given ORF with scores of HP2 versus HP and HP2 versus S2 listed in italics.

(i) orf10(HP2).

Bacteriophage S2 has orf1 and -2, which are unique to S2, but the next hypothetical ORF is orf5, since it is identical to orf5 of HP1. S2 lacks the third and fourth ORFs found in HP1; hence there is no orf3 or orf4 in S2. A similar situation arises in HP2. The gene following rep in HP2 is not identical to orf10 of HP1 (Fig. 4a). Although the inferred gene product shares the same N terminus, a distinct sequence of 270 bp makes up the rest of the 309-bp ORF. Thus, the gene in HP2 is identified as orf10(HP2) to distinguish it from the same region in HP1. Since we were unable to obtain an S2 lysogen, it is unclear whether this gene is unique to HP2. orf10(HP2) is also found in invasive lysogens closely related to R2866 (unpublished observations), so it is not likely to be a spurious finding. Since this phage appears to function without the HP1 equivalents of orf11 and orf12, these genes may not be necessary for phage function. This suggests that HP2 may have lost these nonessential genes in its evolution from HP1. The protein encoded by orf10(HP2) has weak homology to that coded for by orf10 of HP1 (37% identity, 61% similarity) and may serve a similar purpose.

(ii) Lytic transcript differences.

Downstream of orf10(HP2), the nucleotide sequence of HP2 is similar to that of HP1. One large difference occurs between bases 15992 and 17307, including orf21 and orf22 (Fig. 4a). This region has no known match at the nucleotide level in GenBank. However, the putative products of these genes each share 64% similarity and 42% identity (respectively) in spite of the large difference in nucleotide sequence. This suggests that the function of these gene products is conserved. As with most of the genes in this transcript, a function is not known or suggested by motif searches. orf22 was implicated as the location of the ts2 mutation in HP1 that produces a tailless phage (14). If orf22 is involved in some aspect of tail biosynthesis, our data suggest that the tail structures may be different between HP1 and HP2.

HP2 orf27 also differs from HP1 (Fig. 4a). A change in the nucleotide sequence yields a mosaic with a nearly identical N terminus and a divergent C terminus compared to those of HP1. The last 50 amino acids of the orf27(HP2) gene product are identical to those of orf27 of HP1. This suggests a conserved function for the N terminus of this protein. As in orf21 and orf22, it could also be hypothesized that differences in orf27 account for some of the phenotypic differences with regard to plaquing and lysogenization.

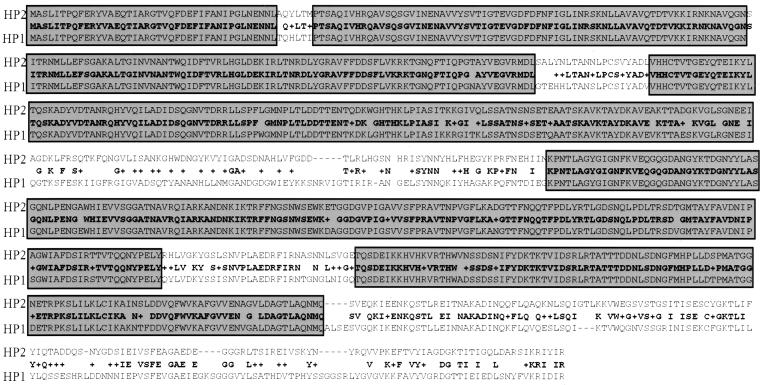

There are two changes in the sequence of HP2 orf31 in comparison to that of HP1 (Fig. 7). Based on homology to P2 and phage 186, orf31 is thought to encode the tail fibers of the bacteriophage (9). While the protein product of orf31(HP2) is nearly identical to that of orf31 in HP1 for the N-terminal 360 amino acids, the sequence of amino acids 361 to 440 is unique and not highly conserved. This region is followed by near-complete identity until HP2 position 606, where there are some conserved changes until residue 638. There is only modest conservation of the 79 amino acids at the C terminus. If this ORF encodes the tail fibers, it is highly suggestive of an altered binding motif at the C terminus that may allow HP2 to distinguish its host from other H. influenzae strains. The variation across the middle of this ORF may alter the three-dimensional structure of the tail fiber or allow it to be presented to the host surface in a slightly different orientation.

Our data suggest that HP2 represents a variant of HP1 that diverged before S2 had evolved to its current structure. In this scenario, HP2 acquired features of S2 before it evolved to its current state of differentiation from HP1. This evolution is supported by a decrease in the number of genes in HP2 and S2 in comparison to the number in HP1. Bacteriophages evolve to efficiency, and losing unnecessary genes is more likely than gaining extra small genes. The loss of the pR1 promoter supports this contention. Evidence from Esposito et al. suggests that pR2 functions as well as pR1, thus negating a need for two promoters at such close proximity (10). cI and cox binding experiments suggest that both pR1 and pR2 are regulated by the same elements. The S2 promoter lacks pR1, suggesting it is not necessary. HP2 contains pR1, but in a configuration that may be less active than the HP1 version (16 bp between the −10 and −35 regions rather than the ideal 17-bp configuration). This comparison places HP2 between HP1 and S2 in the evolving loss of pR1.

Uptake elements.

hUSs consist of a 9-bp core sequence and occur in the Rd KW20 genome, on average, once every 1,249 bp (38). The ability of the H. influenzae phage DNA to be introduced by transformation suggests that the phage genomes would have many hUSs. As an alternative to transfection, transformation could serve as a means for phage DNA dissemination in H. influenzae, and transformation bypasses restriction-modification surveillance, unlike bacteriophage infection (42). The HP1 genome contains only 17 hUSs, an average density lower (0.53/kb) than that of the Rd KW20 genome in general (0.81/kb) (9). HP2 also has 17 hUSs, although at different locations from HP1. We have found that bacteriophage DNA containing a kanamycin resistance cassette transforms with frequencies equivalent to those of chromosomal DNA (containing antibiotic resistance markers) into competent strain Rd KW20 (unpublished observation).

Attachment sites.

The integration site for HP1 and S2 is the stem-loop of the gene encoding tRNALeu (18, 20, 35). The attP target for HP2 is the same (data not shown). The anticodon stem-loop of the tRNALeu is in the middle of an operon encoding tRNALys, tRNALeu, and tRNAGly. As in HP1 and S2, the attP site in HP2 carries duplication of these genes to maintain transcription into functional tRNA molecules. More than one chromosomal attachment site has been described in strain Rd KW20 based on the presence of phage DNA in different SmaI fragments of chromosomal DNA (22). Since the SmaI restriction fragment patterns determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis differ between Rd KW20 and strain R2866, comparing the usage of these alternate attachment sites by HP2 is not possible.

We conclude that HP2 is closely related to HP1 but has a different host: unencapsulated H. influenzae.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI44002 and T32 AI07276 to A. L. Smith.

We thank Joe Forrester of the University of Missouri for assistance with the GCG software and data analysis programs. We are indebted to Jane Setlow for assistance with experimental design and Sol Goodgal for clarification of the origin of H. influenzae phages.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman, H., and M. S. DuBow. 1987. Viruses of prokaryotes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 2.Alexander, H. E., and G. Leidy. 1953. Induction of streptomycin resistance in sensitive Hemophilus influenzae by extracts containing desoxyribonucleic acid from resistant Hemophilus influenzae. J. Exp. Med. 97:17-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnhart, B. J., and S. H. Cox. 1968. Radiation-sensitive and radiation-resistant mutants of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 96:280-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendler, J. W., and S. H. Goodgal. 1968. Prophage S2 mutants in Haemophilus influenzae: a technique for their production and isolation. Science 162:464-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boling, M. E., D. P. Allison, and J. K. Setlow. 1973. Bacteriophage of Haemophilus influenzae. III. Morphology, DNA homology, and immunity properties of HPlcl, S2, and the defective bacteriophage from strain Rd. J. Virol. 11:585-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boling, M. E., J. K. Setlow, and D. P. Allison. 1972. Bacteriophage of Haemophilus influenzae. I. Differences between infection by whole phage, extracted phage DNA and prophage DNA extracted from lysogenic cells. J. Mol. Biol. 63:335-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cope, L. D., R. Yogev, U. Muller-Eberhard, and E. J. Hansen. 1995. A gene cluster involved in the utilization of both free heme and heme:hemopexin by Haemophilus influenzae type b. J. Bacteriol. 177:2644-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, J., A. L. Smith, W. R. Hughes, and M. Golomb. 2001. Evolution of an autotransporter: domain shuffling and lateral transfer from pathogenic Haemophilus to Neisseria. J. Bacteriol. 183:4626-4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito, D., W. P. Fitzmaurice, R. C. Benjamin, S. D. Goodman, A. S. Waldman, and J. J. Scocca. 1996. The complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage HP1 DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2360-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito, D., J. C. Wilson, and J. J. Scocca. 1997. Reciprocal regulation of the early promoter region of bacteriophage HP1 by the Cox and Cl proteins. Virology 234:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewing, B., and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8:186-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzmaurice, W. P., R. C. Benjamin, P. C. Huang, and J. J. Scocca. 1984. Characterization of recognition sites on bacteriophage HP1c1 DNA which interact with the DNA uptake system of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Gene 31:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzmaurice, W. P., and J. J. Scocca. 1983. Restriction map and location of mutations on the genome of bacteriophage Hp1c1 of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Gene 24:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, and J. M. Merrick. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon, D., C. Desmarais, and P. Green. 2001. Automated finishing with autofinish. Genome Res. 11:614-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakimi, J. M., and J. J. Scocca. 1996. Purification and characterization of the integrase from the Haemophilus influenzae bacteriophage HP1: identification of a four-stranded intermediate and the order of strand exchange. Mol. Microbiol. 21:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harm, W., and C. S. Rupert. 1963. Infection of transformable cells of Haemophilus influenzae by bacteriophage and bacteriophage DNA. Z. Vererbungsl. 94:336-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser, M. A., and J. J. Scocca. 1990. Location of the host attachment site for phage HPl within a cluster of Haemophilus influenzae tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kauc, L., K. Skowronek, and S. H. Goodgal. 1991. The identification of the bacteriophage HP1c1 and S2 integration sites in Haemophilus influenzae Rd by field-inversion gel electrophoresis of large DNA fragments. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 40:11-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroll, J. S., K. E. Wilks, J. L. Farrant, and P. R. Langford. 1998. Natural genetic exchange between Haemophilus and Neisseria: intergeneric transfer of chromosomal genes between major human pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12381-12385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krüger, D. H., and T. A. Bickle. 1983. Bacteriophage survival: multiple mechanisms for avoiding the deoxyribonucleic acid restriction systems of their hosts. Microbiol. Rev. 47:345-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutter, E., K. Gachechiladze, A. Poglazov, E. Marusich, M. Shneider, P. Aronsson, A. Napuli, D. Porter, and V. Mesyanzhinov. 1995. Evolution of T4-related phages. Virus Genes 11:285-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nizet, V., K. F. Colina, J. R. Almquist, C. E. Rubens, and A. L. Smith. 1996. A virulent nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. J. Infect.Dis. 173:180-186. (Erratum, 178: 296, 1998.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Notani, N. K., J. K. Setlow, and D. P. Allison. 1973. Intracellular events during infection by Haemophilus influenzae phage and transfection by its DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 75:581-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piekarowicz, A., R. Brzezinski, M. Smorawinska, L. Kauc, K. Skowronek, M. Lenarczyk, M. Golembiowska, and M. Siwinska. 1986. Major spontaneous genomic rearrangements in Haemophilus influenzae S2 and HP1c1 bacteriophages. Gene 49:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Samuels, J., and J. K. Clarke. 1969. New bacteriophage of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Virol. 4:797-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandmeier, H. 1994. Acquisition and rearrangement of sequence motifs in the evolution of bacteriophage tail fibres. Mol. Microbiol. 12:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedgwick, B., J. K. Setlow, M. E. Boling, and D. P. Allison. 1975. Minicell production and bacteriophage superinducibility of thymidine-requiring strains of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 123:1208-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setlow, J. K., M. E. Boling, D. P. Allison, and K. L. Beattie. 1973. Relationship between prophage induction and transformation in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 115:153-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharetzsky, C., T. D. Edlind, J. J. LiPuma, and T. L. Stull. 1991. A novel approach to insertional mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 173:1561-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skowronek, K. 1998. Identification of the second attachment site for HP1 and S2 bacteriophages in Haemophilus influenzae genome. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 47:7-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skowronek, K., and S. Baranowski. 1997. The relationship between HP1 and S2 bacteriophages of Haemophilus influenzae. Gene 196:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skowronek, K., A. Piekarowicz, and L. Kauc. 1986. Comparison of HP1c1 and S2 phages of Haemophilus influenzae. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 35:227-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, H. O., J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, R. D. Fleischmann, and J. C. Venter. 1995. Frequency and distribution of DNA uptake signal sequences in the Haemophilus influenzae Rd genome. Science 269:538-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinhart, W. L., and R. M. Herriott. 1968. Genetic integration in the heterospecific transformation of Haemophilus influenzae cells by Haemophilus parainfluenzae deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Bacteriol. 96:1725-1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuy, J. H. 1975. Fate of transforming bacteriophage HP1 deoxyribonucleic acid in Haemophilus influenzae lysogens. J. Bacteriol. 122:1038-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuy, J. H. 1976. Restriction enzymes do not play a significant role in Haemophilus homospecific or heterospecific transformation. J. Bacteriol. 128:212-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuy, J. H. 1978. On the nature of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 44:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuy, J. H., and J. F. Hoffmann. 1971. Influence of transformability on the formation of superinfection double lysogens in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Virol. 7:127-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilcox, K. W., and H. O. Smith. 1975. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Haemophilus influenzae deficient in an adenosine 5′-triphosphate-dependent deoxyribonuclease activity. J. Bacteriol. 122:443-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams, B. J., G. Morlin, N. Valentine, and A. L. Smith. 2001. Serum resistance in an invasive, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain. Infect. Immun. 69:695-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]