Abstract

In Klebsiella aerogenes, the gdhA gene codes for glutamate dehydrogenase, one of the enzymes responsible for assimilating ammonia into glutamate. Expression of a gdhAp-lacZ transcriptional fusion was strongly repressed by the nitrogen assimilation control protein, NAC. This strong repression (>50-fold under conditions of severe nitrogen limitation) required the presence of two separate NAC binding sites centered at −89 and +57 relative to the start of gdhA transcription. Mutants lacking either or both of these sites lost the strong repression. The distance between the two sites was less important than the face of the helix on which they lay. Insertion or deletion of 10 bp between the sites had little effect on the strong repression, but insertion of 5 bp or deletion of either 5 or 15 bp decreased the repression significantly. We propose that the strong repression of gdhAp-lacZ expression requires an interaction between the NAC molecules bound at the two sites. A weaker repression of gdhAp-lacZ expression (about threefold) required only the NAC site centered at −89. This weaker repression appears to result from NAC's ability to prevent the action of a positive effector the target of which overlaps the NAC binding site centered at −89. Point mutations and deletions of this region result in the same threefold reduction in gdhAp-lacZ expression as the presence of NAC at this site.

Enteric bacteria such as Klebsiella aerogenes and Escherichia coli use two routes to assimilate ammonia from the growth medium into organic material (16). When ammonia is abundant, glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) can reductively aminate α-ketoglutarate in an NADPH-dependent reaction that yields glutamate directly. When the concentration of ammonia is too low to be efficiently fixed by GDH, which has a Km for ammonia in the millimolar range (17), enteric bacteria use the other route for ammonia fixation via the combined action of glutamine synthetase and glutamate synthase. Either route is effective when ammonia is abundant, although GDH confers a distinct growth advantage under conditions of energy limitation (9). However, under conditions of nitrogen limitation, GDH serves little or no function in ammonia fixation.

The formation of GDH is subject to complex regulation. In K. aerogenes, GDH is strongly repressed under conditions of nitrogen-limited growth (16). This repression requires the well-studied Ntr system and is mediated by the nitrogen assimilation control protein, NAC, the synthesis of which is under direct Ntr control (14). Under conditions of nitrogen-limited growth, the Ntr system activates nac gene expression, and the resulting NAC accumulation represses gdhA expression. Under conditions of nitrogen excess, the Ntr system fails to activate nac gene expression, and in the absence of NAC, gdhA expression is not repressed. Mutants that lack NAC do not repress GDH formation under conditions of nitrogen-limited growth, and in mutants in which NAC expression is inducible by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), GDH expression is repressed by IPTG, independent of the quality of the nitrogen source (26). It is clear that NAC is both necessary and sufficient for the repression of GDH formation in vivo, but the mechanism of this repression is unknown. In addition, GDH formation is repressed about threefold when lysine is present in the growth medium (11). Little is known about this phenomenon, but the target for the effector appears to overlap a region where NAC binds (21). Finally, GDH expression in K. aerogenes is also repressed about 20-fold by growth in rich medium. However the focus of the experiments described here is the nitrogen regulation of GDH expression by NAC.

NAC is a homodimeric protein with a subunit molecular weight of 32,759 (25). It is a member of a large family of transcriptional regulatory proteins known as the LysR family, many of which are homotetramers (24). In vitro transcription experiments have shown that purified NAC is able to activate transcription of the hut operons and repress the nac gene of K. aerogenes (5, 6). Experiments with the nac gene under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter have shown that NAC is an activator of the ureDABCEFG (26), putP (14), codBA (W. B. Muse and R. A. Bender, unpublished observations), and dadAB operons (10), as well as a repressor of gdhA (26) in K. aerogenes. NAC activates transcription by binding to a site on the DNA near the RNA polymerase binding site, often at −64 relative to the start of transcription. The sites to which NAC binds contain the nucleotides ATA-N9-TAT, and these have been shown to be important for NAC binding and for NAC's ability to activate transcription (22). Point mutations affecting these six nucleotides reduce, but do not generally abolish, the ability of NAC to bind and activate (22). Promoters in which NAC represses transcription do not contain this sequence, but do have a sequence that is similar, ATA-N9-GAT (or its equivalent on the opposite strand, ATC-N9-TAT), which is thought to serve as a binding site for NAC in these promoters (5; unpublished observation).

As part of our long-term interest in the role of NAC in bacterial nitrogen metabolism, we began a study of NAC-mediated repression of GDH formation in K. aerogenes and found that the mechanism is complex and involves an interaction between two separate NAC binding sites near the promoter of the gdhA gene coding for GDH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids.

The species K. aerogenes has been subsumed into the species Klebsiella pneumoniae; however, we have retained the older name for strains derived from strain W70 for historical reasons. All E. coli strains used were derived from strain K-12. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT-2 is referred to here as S. enterica. Descriptions and genotypes of K. aerogenes strains, plasmids, and fusions are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of strains, plasmids, and fusions used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or fusion | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| KC2668 | Δ[bla]-2 hutC515 dadA1 | 12 |

| KC4660 | KC2668 hutC::neo hutC::attλ | This work |

| KC4661 | KC2668 hutC::neo hutC::attλ/pCB832 | This work |

| KC4810 | KC4661 nac-203::Tn5-131 (λRZ-5ΦCB532) | This work |

| KC4834 | KC4661 (λRZ-5ΦCB532) | This work |

| KB4921a | gltB200 gln-45 nac-1 zed-2::Tn5-131 | This work |

| KC4929 | KC4661 zed-2::Tn5-131 (λRZ-5ΦCB532) | This work |

| KC4930 | KC4661 zed-2::Tn5-131 nac-1 (λRZ-5ΦCB532) | This work |

| KC5084 | KC4661 gdhA1 (λRZ-5ΦCB532) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCB832 | 2.4 kb EcoRI:HindIII fragment carrying lamB from pTROY cloned into pGB2 | This work |

| pGB2 | Low-copy cloning vector | 3 |

| pGDH4 | gdhA cloned into pUC19 | 13 |

| pRS415 | Promoterless lacZYA reporter for operon fusions with replication origin of pBR322 | 30 |

| pTROY11 | IS1::lamB carried in plasmid pBR322; makes strains susceptible to infection by phage λ | 4 |

| Fusionsb | ||

| ΦCB532 | gdhAp (−116 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1064 | ΦCB532 with A-to-T change at −96 | This work |

| ΦCB1065 | ΦCB532 with A-to-T change at −96 and T-to-A change at +64 | This work |

| ΦCB1067 | ΦCB532 with T-to-A change at +64 | This work |

| ΦCB1106 | gdhAp (−82 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1109 | ΦCB532 with A-to-T change at +13 and G-to-A change at +16, generating an XbaI site | This work |

| ΦCB1121 | gdhAp (−82 to +23) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1142 | gdhAp (−98 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1143 | gdhAp (−58 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1144 | gdhAp (−41 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1202 | gdhAp (−116 to +23) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1230 | ΦCB532 with 10-bp insertion caused by replacing AAGG at +13 to +16 with TAGAAGCTTCTAGA | This work |

| ΦCB1243 | gdhAp (−68 to +75) fused to lacZ | This work |

| ΦCB1246 | ΦCB532 with 5-bp insertion of TCGAG between +12 and +13 | This work |

| ΦCB1309 | ΦCB532 with 10-bp deletion of CAAGGACCGA between +12 and +21 | This work |

| ΦCB1326 | ΦCB532 with 15-bp deletion of CAAGGACCGAATCAT between +12 and +26 | This work |

| ΦCB1331 | ΦCB532 with 5-bp deletion of CAAGG between +12 and +16 | This work |

This strain is not derived from KC2668 and carries the wild-type alleles of hutC and dadA, as well as plasmid pPN100.

All fusions are derived from recombination of λRZ-5 with derivatives of plasmid pRS415. Nucleotide sequences are given in the 5′-to-3′ direction for the coding strand and numbered relative to the gdhAp transcription initiation nucleotide at position +1.

Growth conditions and enzyme assays.

Cells were grown in glucose minimal medium as described previously (14) and assayed for GDH and β-galactosidase by standard methods (14). Protein concentration was determined by the method of Lowry with whole cells as described previously (14). Specific activities are reported as the average of two or more assays with a standard error of <10%.

Sequencing of the K. aerogenes nac region.

The DNA sequence of the region downstream of the K. aerogenes nac gene was determined as previously described (7) with subclones derived from pCB205 (25).

Bacteriophage λ lysogens of K. aerogenes.

K. aerogenes strain W70, from which all strains in this report were derived, is resistant to bacteriophage λ. The plasmid pTROY11 (4) carrying the IS1::lamB fusion has been used to sensitize K. aerogenes to bacteriophage λ. The IS1::lamB fusion was cloned from pTROY11 into pGB2 (3), yielding pCB832. Even strains of K. aerogenes that carry pCB832 are not easily lysogenized by λ, because K. aerogenes lacks an attλ locus. Therefore, a derivative of K. aerogenes strain KC2668 was isolated that carried the attλ locus cloned into the hutC gene. In addition, a gene encoding resistance to kanamycin was also cloned into the hutC gene to facilitate the manipulation of attλ. Thus, the hutC gene of the resulting strain, KC4660, carries three different mutations: hutC515, which renders the hut repressor inactive to start with, an insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene (useful for genetic selections), and the attλ locus. Strain KC4661, which carries pCB832 as well as the hutC::attλ allele, can be infected by bacteriophage λ, and stable lysogens integrated at the attλ locus can be isolated.

The λ prophages used in this study were all derived from λRZ-5 (20) and carry fusions that were originally generated in plasmid pRS415 (27), essentially as described previously (8). Many of the lysogens isolated contained more than one prophage at the attλ locus. To enrich for monolysogens, the initial selection of the λRZ-5 derivatives was made on low concentrations of ampicillin (5 or 7.5 μg/ml). The copy number of the prophage was determined based on the pattern of products generated by Southern blotting carried out as previously described (7) or from the pattern of PCR products generated with the appropriate primers (23). All strains used here were confirmed to carry a single copy of λ integrated at the attλ locus.

Construction of nac+ and nac-1 strains of K. aerogenes.

A pair of congenic strains, differing at the nac locus, was isolated by transducing derivatives of strain KC4661 to tetracycline resistance with phage P1 grown on KB4921. KB4921 carried a Tn5-131 insertion linked to nac (26). Tetracycline-resistant transductants were screened for the presence of the nac-1 allele by scoring their ability to grow on glucose minimal medium with proline as the sole nitrogen source. Those transductants that had a Nac− phenotype (poor growth) were designated zed-2::Tn5-131 nac-1; those that scored Nac+ (good growth) were designated zed-2::Tn5-131.

Analysis of the nac-1 deletion.

Chromosomal DNA was purified from strains KC4929 (nac+) and KC4930 (nac-1) by using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems). Preliminary Southern analysis was carried out at high stringency with PstI-digested chromosomal DNA and probes derived from subclones of pCJ5 (25) as previously described (7). PCR amplification of the nac region from undigested KC4929 and KC4930 chromosomal DNA templates was carried out with convergent primers corresponding to regions within orfX (primer A, AATATGCTGCTCGAAACCTATCAGCG) and o278 (primer B, CTGAACTGTTCGCGCCTCGCTTCCCG) (Fig. 1), provided by Gibco/BRL, and rTth polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) under reaction conditions specified by the supplier. The PCR products were analyzed on 1% TAE-agarose gels (15) and the 644-bp PCR product amplified from the nac-1 region of KC4930 was purified and the sequence was determined from both strands by using primers A and B as previously described (7).

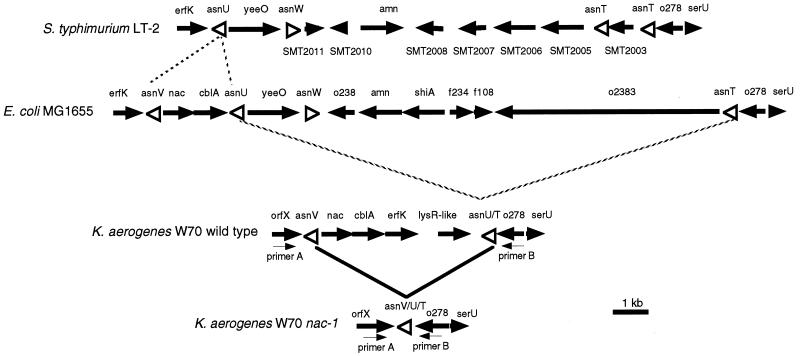

FIG. 1.

Organization of genes in the nac region. The bottom two lines represent the arrangement of genes in the nac region of the K. aerogenes W70 wild type and nac-1 mutant, respectively. The homologous regions from S. enterica strain LT-2 and E. coli K12 strain MG1665 are shown in lines 1 and 2 for comparison. Arrows and arrowheads indicate the position, approximate extent, and polarity of open reading frames (solid arrows) and tRNA genes (open arrowheads). The arrows labeled primer A and primer B indicate the position and polarity of the primers used in PCR to amplify the nac region from wild-type and nac-1 strains of K. aerogenes. Dashed diagonal lines indicate boundaries of hypothetical deletion events that may have occurred in evolutionary time. Solid diagonal lines indicate the recombination-mediated deletion of the material between asnV and asnU/T in wild-type K. aerogenes that resulted in the nac-1 deletion mutation. S. enterica annotations beginning with “SMT” have no orthologs in E. coli or K. aerogenes. Sizes are only approximately to scale, and asparaginyl tRNA (asn) genes are particularly exaggerated.

In vitro analysis of NAC interactions with the gdhA promoter.

In general, the methods outlined by Maniatis et al. (15) were used in manipulating DNA. DNA sequences were determined as previously described (7). The purification of NAC, mobility shift analysis, and DNase I footprint analysis were carried out as described previously (6). For the footprints in Fig. 2B, 0.16 pmol of radiolabeled DNA was incubated with increasing amounts of NAC dimer (from 45 ng to 3.67 μg) and treated with 0.0023 U of DNase I. The samples were boiled in the presence of formamide, and the digestion products were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography.

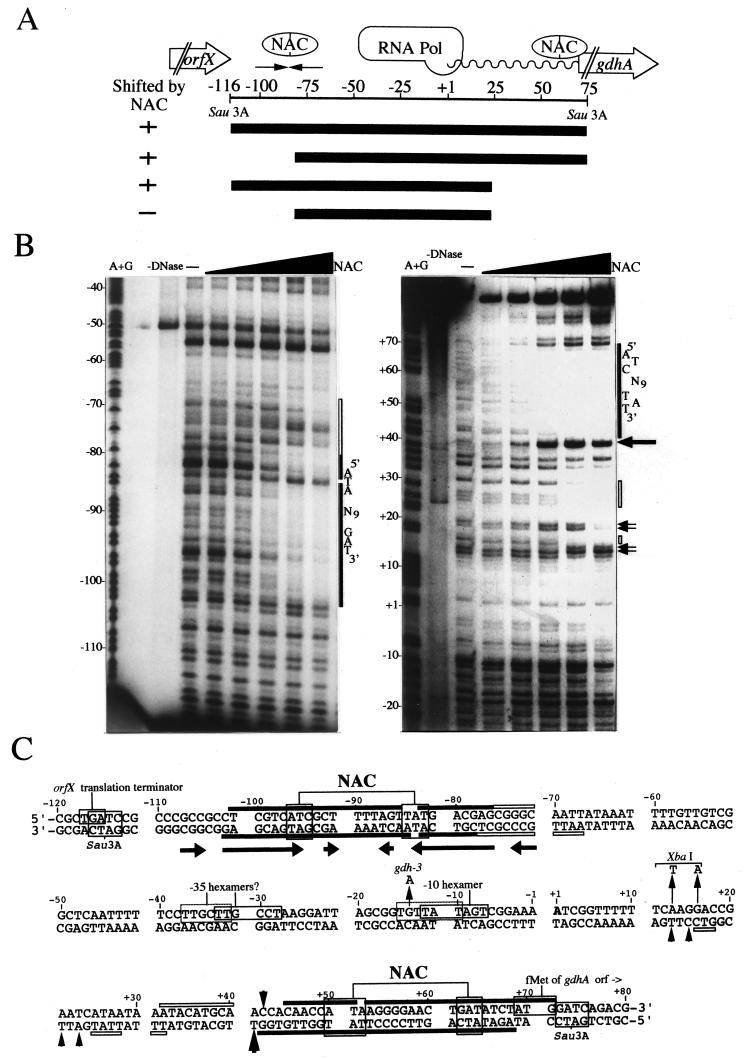

FIG.2.

Interaction of NAC with the gdhA promoter region. (A) Schematic drawing of the gdhA promoter region. The numbers represent positions relative to +1, the start of gdhA transcription (represented by a wavy line). NAC, the core region protected by NAC; RNA Pol, orfX, and gdhA, the inferred extents of RNA polymerase binding, the open reading frame upstream from gdhA, and the coding region of gdhA, respectively. The convergent arrows represent the region of dyad symmetry discussed in the text. A plus in the column labeled “Shifted by NAC” indicates that the DNA fragment represented by the heavy line was bound by NAC in a gel mobility shift assay. A minus indicates that the fragment was not bound by NAC. (B) DNase I footprint of NAC bound to the gdhA promoter region. Numbers to the left correspond to the numbers in panel A. Letters to the right indicate the important ATA-N9-GAT sequences. The solid and open vertical bars on the right indicate higher- and lower-affinity protection by NAC. Arrows represent hypersensitive sites. Only one strand is shown for each NAC binding site. DNA was present at 0.16 pmol, and NAC was present at 45, 135, 405, 1,220, or 3,670 ng. (C). Nucleotide sequence of the gdhA promoter region showing key features. Solid and open bars above and below the sequence indicate regions of higher- and lower-affinity protection by NAC. Horizontal arrows (−108 to −71) indicate the region of dyad symmetry. Arrows at −14 and at +13 and +16 indicate the gdhA3 mutation and the mutational changes that generated an XbaI site, respectively. Arrowheads at +13, +15, +21, +23, +41, and +42 indicate sites of DNase I hypersensitivity in the presence of NAC.

RESULTS

The nac-1 mutation.

In earlier studies, we noticed that some nac alleles have stronger phenotypes than others (14). In particular, we noted that even mutations that truncated nac after amino acid 100 (of 305) still retained considerable ability to activate transcription of the hut operons (19). In the original screen of several hundred nac mutations (1), nac-1 was chosen for its tight phenotype. Preliminary Southern blot analysis of the nac region of wild-type and nac-1 strains suggested that the nac-1 lesion represented a deletion of at least some of the nac open reading frame (data not shown). Figure 1 shows the genetic organization in the nac region of K. aerogenes deduced from previously published data and further DNA sequence analysis of pCB205 (25). The corresponding regions from S. enterica and E. coli are shown for comparison. Among the genes present in this region of the K. aerogenes chromosome are two asparaginyl tRNA genes, designated asnV and asnU/T, which represent direct repeats of 98 bp separated by approximately 4 kb. It was tempting to speculate that the spontaneously derived nac-1 mutation might be a recombination-mediated deletion of the 4-kb region between these two homologous asn genes. To test this notion, the regions between the orfX and o278 genes were amplified from the chromosomes of wild-type and nac-1 strains by using primers indicated in Fig. 1 and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis along with appropriate size standards. The PCR amplification from the wild-type chromosomal template repeatedly yielded the predicted major product of approximately 4.4 kb, as well as minor products of approximately 1.8 and 0.65 kb (data not shown). In contrast, the amplification from the nac-1 chromosomal template yielded a single band of 650 bp (data not shown). The 650-bp fragment amplified from the nac-1 chromosome was purified, and its DNA sequence was determined. The sequence of this fragment initiated within the orfX open reading frame, spanned the orfX-asnV intergenic region, included a sequence identical to those in both the asnV and asnU/T genes, spanned the asnU/T-o278 intergenic region, and finally ended within the o278 open reading frame. Thus, the nac-1 lesion is indeed a deletion of all the material between asnV and asnU/T in K. aerogenes.

Transcriptional regulation of gdhA by NAC.

The activity of GDH in K. aerogenes is repressed under conditions of nitrogen limitation (16), and NAC is both necessary and sufficient to reduce GDH activity in cells even under conditions of nitrogen excess (1, 26). However, except for a single primer extension experiment (22), it has never been demonstrated whether this regulation occurs at the transcriptional level. Moreover, the GDH of E. coli has been reported to be subject to phosphorylation, which might have regulatory consequences (13). Therefore, we used fusions of the gdhA promoter (gdhAp) to a promoterless lacZ gene to demonstrate that NAC-mediated regulation of GDH occurred at the transcriptional level.

The gdhAp region from −116 to +75 relative to the gdhA transcription start site was fused to a promoterless lacZ gene. The DNA in this fusion (ΦCB532) spans the region from the 3′ end of an open reading frame upstream from gdhA to the coding sequence of gdhA. This fusion was then transferred to bacteriophage λRZ-5 (20) and used to lysogenize strain KC4661. Southern blots and PCR analysis confirmed that KC4834 was a monolysogen carrying a single copy of λRZ-5ΦCB532 integrated into the attλ site present within the chromosomal hutC gene of KC4661 (data not shown). Derivatives of KC4834 carrying gdhA1, nac203::Tn5-131, or nac-1 were constructed by P1 transduction. The nac-1 allele was moved by taking advantage of the zed-2::Tn5-131 mutation, an insertion of the tetracycline resistance-encoding transposon Tn5-131 that is about 60% linked to nac (26). GDH and β-galactosidase activities were measured in these strains grown in a nitrogen-excess medium containing 0.2% (wt/vol) ammonia plus 0.2% glutamine as nitrogen sources (GNgln), a moderately nitrogen-limiting medium containing 0.04% glutamine at as the sole nitrogen source (Ggln), and a severely nitrogen-limiting medium containing 0.2% sodium glutamate as the sole nitrogen source (Gglt). The doubling times of KC4834 and its derivatives in GNgln, Ggln, and Gglt were about 60, 80, and 300 min, respectively, and were not strongly influenced by the genotypes of the strains.

The data in Table 2 argue strongly that the NAC-mediated repression of GDH expression is indeed transcriptional. The β-galactosidase activities of strain KC4834 (the wild-type strain carrying the gdhA-lacZ fusion ΦCB532) were repressed about 9- and 70-fold in cells grown under moderate or severe nitrogen limitation, respectively, relative to nitrogen excess (GNgln medium). A congenic strain lacking GDH activity (KC5084) showed a similar response to nitrogen limitation, and thus the presence of an active GDH is not essential for the regulation of gdhAp expression. Similarly, the zed-2 mutation that was used to cotransduce the nac-1 allele had little or no effect on the nitrogen regulation of gdhAp (compare strains KC4834 and KC4929). However this repression was dependent on NAC, since strains carrying either the nac-1 deletion or nac-203 (an insertion of a Tn5 element at amino acid 199 of the NAC sequence) (25) showed no repression of β-galactosidase formation in response to nitrogen limitation (Table 2, strains KC4930 and KC4810). Moreover, the similarity of those two strains, combined with the fact that insertions in nac are not polar on cbl expression (25), argues that the other genes deleted in the nac-1 deletion (cbl, erfK, and the “lysR-like” open reading frame) play no role in the nitrogen regulation of gdhA expression. This was confirmed by comparing a strain carrying a low-copy clone of the wild-type nac gene (in plasmid pGB2) and the nac-1 deletion on the chromosome. The clone contains only nac and fully complements the defect in nitrogen regulation caused by the nac-1 deletion (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Specific activity of glutamate dehydrogenase and β-galactosidase from strains carrying a fusion (ΦCB532) of the gdhA promoter to lacZ

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Medium | Sp act (U/mg)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosidaseb | GDH | ||

| KC4834 (wild type) | GNglnc | 6,700 | 340 |

| Gglnd | 790 | 65 | |

| Gglte | 95 | 10 | |

| KC4929 (zed-2) | GNgln | 5,970 | 365 |

| Ggln | 610 | 75 | |

| Gglt | 94 | 20 | |

| KC4930 (zed-2 nac-1) | GNgln | 6,130 | 370 |

| Ggln | 9,000 | 720 | |

| Gglt | 6,030 | 340 | |

| KC4810 (zed-2 nac-203) | GNgln | 6,280 | 350* |

| Ggln | 9,440 | 540 | |

| Gglt | 3,800 | 180 | |

| KC5084 (gdhA1) | GNgln | 7,540 | 19 |

| Ggln | 664 | 11* | |

| Gglt | 97 | 11* | |

Specific activities are the average of two or more assays and have a standard error of 10% or less, except where marked by an asterisk.

β-Galactosidase activity is measured as activity from the gdhA-lacZ operon fusion ΦCB532 present in single copy at the hutC::attλ site. β-Galactosidase activity from the endogenous K. aerogenes lac operon plus the promoterless reporter construct was less than 10 U/mg under these conditions.

GNgln is nitrogen excess medium and contains 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.2% (wt/vol) each ammonium sulfate and l-glutamine.

Ggln is moderately-nitrogen-limiting medium and contains 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.04% (wt/vol) l-glutamine.

Gglt is severely-nitrogen-limiting medium and contains 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.2% (wt/vol) monosodium glutamate.

A closer comparison of the two different nac mutants, KC4810 and KC4930, reveals a similarity and a slight difference. The two strains were similar in that both showed an increase in β-galactosidase activity (as well as GDH) under moderate nitrogen limitation (Ggln). This increase, as great as twofold, is regularly seen in nac mutants of both K. aerogenes and E. coli. The two strains differed in that strain KC4810 (nac-203) showed a nearly twofold repression of both GDH and β-galactosidase expression in Gglt medium, whereas KC4930 (nac-1) showed little or no repression in Gglt. We have previously noticed that many nac alleles retain various amounts of residual NAC activity (14, 19; unpublished data). Since the nac-203 mutation retains the first 199 amino acids of wild-type NAC, nac-203 might not be a complete null mutation.

The regulation of GDH activity in the strains shown in Table 2 is similar to that of β-galactosidase, but the effect is less dramatic. GDH activities are repressed about 5- and 20-fold in Ggln and Gglt media. This contrasts with the 9- and 70-fold repression of β-galactosidase. This difference can be explained by the existence of a second GDH-like activity in K. aerogenes cells that typically appears as 10 to 30 U of GDH (11) (Table 2, strain KC5084). Therefore, we have focused on the β-galactosidase activity as a reporter for gdhAp activity. Finally, the data in Table 2 demonstrate that all of the cis-acting sequences required for regulation of gdhAp expression are present on the Sau3A fragment that extends from −116 to +75 relative to the gdhA transcription start site and thus are present in the fusion ΦCB532.

Two binding sites for NAC near the gdhA promoter.

The same Sau3A fragment used to generate the fusion was examined for its ability to bind purified NAC. With a gel mobility shift assay (not shown), two distinct regions were identified, each of which strongly interacted with NAC (Fig. 2A). DNase I footprint analysis showed that NAC protected two distinct regions from digestion: one centered at −89 and the other centered at +57 (Fig. 2B). The promoter-proximal boundaries of both sites were somewhat indistinct, whereas the promoter-distal boundaries were more sharply defined. The sites were well separated from each other, and their footprints differed from each other in several ways.

The upstream region protected by NAC (centered at −89) lacked obvious regions of NAC-induced DNase I hypersensitivity and contained a typical 26-bp protected region (called a “core site” here). This was similar to that seen at the hut promoter, where NAC serves as a transcriptional activator (6). The upstream NAC binding site overlaps the central portion of a 37-bp inverted repeat (13 matches per half-site). When this inverted repeat sequence was placed between the lac promoter and the lacZ coding sequence, β-galactosidase activity was reduced by 75% (data not shown), suggesting that this inverted repeat functions as a transcriptional terminator for the open reading frame of unknown function that lies upstream from gdhA.

In contrast to the relative simplicity of the upstream region's footprint, the footprint at the downstream region was more complex. Like the upstream region, the footprint of the downstream region contained a typical core site (centered at +57). However, on the promoter-proximal side, several additional features were seen. There was a pronounced region of NAC-induced DNase I hypersensitivity near position +40. There was a region of lower-affinity protection between +15 and +40 (called the “extended footprint”). In addition, there were regions of weaker DNase I hypersensitivity near positions +14 and +22. The complexity of the downstream footprint was similar to that seen in the nac promoter, where NAC acts as an antiactivator (5).

Near the center of the core footprints of both the upstream and downstream sites, we noticed the sequence ATA-N9-GAT (or its inverted equivalent, ATC-N9-TAT), a sequence also found near the core region of the NAC footprint at the nac promoter (5). This sequence motif is similar to a more symmetric sequence, ATA-N9-TAT, found within NAC binding sites at promoters activated by NAC (6). Thus, we suspect that the sequence ATA-N9-GAT and closely flanking nucleotides contain information important for the binding of NAC to the two sites associated with the gdhA promoter.

Both NAC binding sites are necessary for repression of gdhA.

To determine the role of these two sites in the repression of gdhA expression by NAC, we isolated derivatives of fusion ΦCB532 with deletion of the upstream site, the downstream site, or both sites (ΦCB1106, ΦCB1202, and ΦCB1121, respectively). Monolysogens containing these fusions were used to construct congenic nac+/nac-1 pairs, and β-galactosidase activity was measured as a reporter of gdhAp activity to determine the effects of the deletions on NAC-mediated repression.

Deletion of the region that contains the upstream NAC site (ΦCB1106) has two independent effects on the expression of β-galactosidase activity: one affecting positive regulation and one affecting negative regulation. The wild-type fusion (ΦCB532) expresses about threefold less β-galactosidase when the GNgln medium is supplemented with lysine (Table 3). In contrast, the deleted fusion (ΦCB1106) is unresponsive to the lysine supplement and expresses β-galactosidase at a level similar to that of the wild-type fusion seen in GNgln medium supplemented with lysine. In other words, there must be a lysine-sensitive factor that interacts with the upstream region and stimulates transcription from gdhAp. This factor is unable to stimulate the upstream deleted fusion, resulting in a threefold reduction in the basal (GNgln) level relative to the wild type (Table 3, cf. ΦCB532 and ΦCB1106). This lysine-sensitive effector has been described earlier and is seen in both Nac+ and Nac− strains grown under nitrogen-excess conditions (11, 21). As seen with the wild-type fusion, the activity of the upstream deleted fusion in the Nac− strain under moderate nitrogen limitation is elevated relative to that seen under nitrogen excess. This NAC-independent stimulation of gdhAp by moderate nitrogen limitation means that NAC effects are best described by comparing the congenic Nac+/Nac− pairs of strains. The deletion of the upstream NAC binding site (ΦCB1106) virtually eliminated the repression by NAC, with the deleted fusion showing less than a twofold effect of NAC (ΦCB1106, cf. Nac+ and Nac− strains). This contrasts with the strong repression seen with the wild-type fusion (ΦCB532), with which a 60-fold repression is seen.

TABLE 3.

β-Galactosidase activity from gdhA-lacZ operon fusions with deletions and insertions in the gdhA promoter region

| Fusion | Descriptiona | Mediumb | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg)c

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nac+ | Nac−d | |||

| CB532 | Wild type | GNgln | 5,860 | 6,310 |

| GNgln+lys | 1,680 | NDe | ||

| Ggln | 610 | 9,000 | ||

| Gglt | 95 | 6,030 | ||

| CB1106 | Δ−82 | GNgln | 2,040 | 2,000 |

| GNgln+lys | 1,930 | ND | ||

| Ggln | 4,140 | 4,720 | ||

| Gglt | 2,380 | 4,350 | ||

| CB1202 | Δ+23 | GNgln | 1,140 | 1,400 |

| Ggln | 1,260 | 2,370 | ||

| Gglt | 810 | 1,830 | ||

| CB1121 | Δ−82, Δ+23 | GNgln | 430 | 420 |

| Ggln | 1,370 | 1,160 | ||

| Gglt | 1,180 | 1,440 | ||

| CB1064 | A(−96)T | GNgln | 2,680 | 2,460 |

| GNgln+lys | 2,070 | ND | ||

| Ggln | 1,340 | 5,180 | ||

| Gglt | 610 | 3,870 | ||

| CB1067 | T(+64)A | GNgln | 5,660 | 5,920 |

| Ggln | 2,910 | 8,670 | ||

| Gglt | 1,320 | 5,860 | ||

| CB1065 | A(−96)T, T(+64)A | GNgln | 2,840 | 2,240 |

| Ggln | 4,760 | 5,130 | ||

| Gglt | 2,560 | 4,390 | ||

| CB1109 | XbaI@+12 | GNgln | 6,090 | 6,100 |

| Ggln | 950 | 9,150 | ||

| Gglt | 95 | 7,060 | ||

| CB1230 | +10@+12 | GNgln | 6,880 | 6,960 |

| Ggln | 1,030 | 8,620 | ||

| Gglt | 136 | 7,200 | ||

| CB1246 | +5@+12 | GNgln | 6,400 | 6,460 |

| Ggln | 2,150 | 10,400 | ||

| Gglt | 760 | 7,140 | ||

| CB1331 | −5@+12 | GNgln | 7,700 | 6,840 |

| Ggln | 1,480 | 8,010 | ||

| Gglt | 410 | 6,220 | ||

| CB1309 | −10@+12 | GNgln | 4,260 | 4,150 |

| Ggln | 550 | 4,960 | ||

| Gglt | 120 | 4,730 | ||

| CB1326 | −15@+12 | GNgln | 7,270 | 7,100 |

| Ggln | 1,520 | 9,090 | ||

| Gglt | 580 | 8,500 | ||

The details of the descriptions of the gdhAp material present in the gdhA-lacZ operon fusions are as follows: wild type, contains all gdhAp from −116 to +75 relative to the start of transcription; Δ−82, all material upstream from position −82 (i.e, from −116 to −83) absent; Δ+23, all material downstream from position +23 absent; A(−96)T, alteration of A at −96 to T; T(+64)A, alteration of T at +64 to A; XbaI@+12, two nucleotides near +12 altered from wild type to generate an XbaI site at +12 as described in Materials and Methods; +10@+12 and +5@+12, insertions of 10 and 5 bp, respectively, at +12; −5@+12, −10@+12, and −15@+12, deletions of 5, 10, and 15 bp, respectively, extending downstream from +12.

Growth media were as described in the legend to Fig. 2. GNgln is nitrogen excess, Ggln is moderately limiting, and Gglt is severely limiting. Lysine (lys) was present at 0.01% (wt/vol) where indicated.

β-Galactosidase activity from the gdhA-lacZ operon fusion indicated in column 1 (present in single copy at hutC::attλ). Specific activities are the average of two or more assays with standard error of less than 10%.

The Nac+ and Nac− strains were KC4661 into which either zed-2::Tn5-131 alone or zed-2::Tn5-131 and nac-1 had been introduced by P1-mediated transduction with selection for the tetracycline resistance associated with Tn5-131.

ND, not determined.

The fusion with the downstream site deleted (Table 3, ΦCB1202) also had a lower basal level than did the wild-type fusion. We do not know whether this is the result of deletion of a region that interacts with yet another effector of gdhA or whether it is simply the result of a different fusion junction. In any event, deletion of the downstream site strongly reduced NAC-mediated repression. Comparing ΦCB1202 in the congenic Nac+/Nac− pair, there was roughly a twofold repression of β-galactosidase by NAC under both moderate and severe nitrogen limitation (Table 3). We suspect that this residual two- to threefold repression results from a competition between NAC and the lysine-sensitive activator for a site or sites within the −116 to −82 region. The fusion lacking both the upstream and downstream sites had similar levels of β-galactosidase in response to moderate and severe nitrogen limitation, regardless of whether the strains were Nac+ or Nac− (Table 3, ΦCB1121).

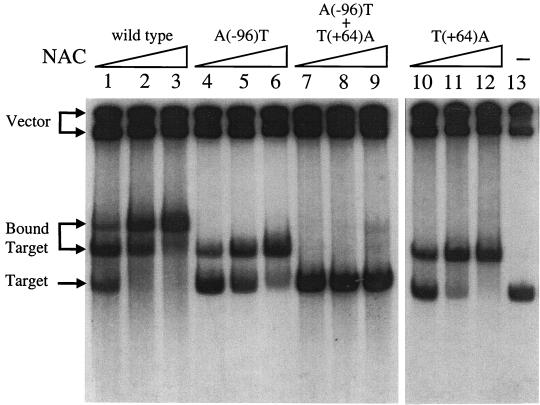

A set of constructs similar to the deletion constructs was generated that carry point mutations within the upstream site, the downstream site, and both sites. Two point mutations, A(−96)T and T(+64)A, change the sequence ATA-N9-GAT (or its inverted equivalent ATC-N9-TAT) found in the upstream and downstream footprints to ATA-N9-GAA. A gel mobility shift assay showed that these mutations abolished NAC binding in vitro (Fig. 3). A wild-type DNA fragment had a double shift in gel mobility shift assays with purified NAC, corresponding to the binding of one and two NAC molecules (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 3). The DNA fragments carrying either the A(−96)T or the T(+64)A single point mutation had a single shift (lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12, respectively). The double mutant carrying both point mutations was not shifted by NAC at all (lanes 7 to 9). Thus, the point mutations did indeed affect nucleotides important for the binding of NAC, at least in vitro.

FIG. 3.

Mobility shift assay of gdhA point mutants. Plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and end labeled with 32P. Labeled DNA (0.5 ng) was mixed with 100 ng of unlabeled calf thymus DNA (100 ng), and this mixture was then incubated with various amounts of NAC. The resulting complexes were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and detected by autoradiography. Lanes: 1 to 3, wild-type gdhAp region; 4 to 6, upstream point mutant A(−96)T in the gdhAp region; 7 to 9, both mutations A(−96)T and T(+64)A in the gdhAp region; 10 to 12, downstream point mutation T(+64)A in the gdhAp region. Lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10 contained 4.4 ng of purified NAC; lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11 contained 13 ng of purified NAC; and lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12 contained 40 ng of purified NAC. Lane 13 contained no NAC. The positions of free gdhAp DNA, bound gdhAp DNA, and vector DNA are indicated to the left of the figure.

The effects of the point mutations upon the activities of fusions in vivo were similar to but less severe than the effects of the deletions (Table 3, ΦCB1064, ΦCB1067, and ΦCB1065). The upstream A(−96)T point mutation reduced the basal activity of the fusion and abolished the lysine sensitivity of the promoter (Table 3, ΦCB1064), just like the deletion. Thus, it appears that the A(−96)T mutation destroyed the target for the lysine-sensitive effector. The A(−96)T and T(+64)A single point mutations each showed less NAC-dependent repression of β-galactosidase expression than the wild-type fusion (Table 3, ΦCB1064 and ΦCB1067). Specifically, the A(−96)T upstream point mutation caused a nearly 6-fold repression by NAC, compared to the wild-type repression of 60-fold. The T(+64)A downstream point mutation caused an approximately fourfold repression by NAC. The double mutant carrying both A(−96)T and T(+64)A, like the double-deletion mutant, showed less than a twofold repression by NAC (Table 3, ΦCB1065).

Phase dependence of the NAC sites.

The strong repression by NAC required two NAC binding sites. To test whether the orientation of these two sites was important for the strong NAC-mediated repression, we introduced insertions and deletions into the wild-type fusion at position +12. First, we confirmed that the XbaI site introduced at +12 to facilitate the mutagenesis had no effect on the strong repression (Table 3, ΦCB1109). An insertion of 10 bp at +12 had no effect on the strong NAC-mediated repression (ΦCB1230), whereas an insertion of 5 bp resulted in significantly less repression, almost as weak as that seen with the downstream point mutation (Table 3, ΦCB1246). When the deletions at +12 were tested, again, deletion of 10 bp had little or no effect on the degree of repression, but deletions of 5 or 15 bp led to less repression (Table 3, ΦCB1331, ΦCB1309, and ΦCB1326). Thus, the relative orientation of the two NAC sites (or the orientation of the downstream site relative to RNA polymerase) is important for the strong repression by NAC.

DISCUSSION

Two widely spaced sites are required for the strong NAC-mediated repression of gdhAp.

In addition, the phasing or dependence upon the face of the helix on which those NAC sites are located is important for the repression, whereas the distance between these phased NAC sites is of less significance. Taken together, these two facts suggest that the NAC-DNA complexes formed at these two sites interact with each other in some way to cause strong repression. Our gel mobility shift analysis did not show any evidence of cooperativity in the binding of NAC to the two sites in vitro, but such data do not rule out cooperativity in vivo. Thus, the nature of the interaction—whether DNA looping, phased bends, cooperative filling of the intervening space, or any of a host of other possibilities—remains unknown.

Although both sites are important for the strong repression, there was a weak repression of about two- or threefold seen when only the upstream NAC site was present. Sequences that overlap the upstream NAC site are important for full gdhA expression in GNgln medium, at least in the absence of lysine (Table 3). The phenotype of the point mutation A(−96)T shows that the binding sites for NAC and for the lysine-sensitive effector NAC overlap. Thus it seems likely that the binding of NAC interferes with the binding of some lysine-sensitive effector to this site. The upstream binding sites for NAC and the lysine-sensitive effector lie within an inverted repeat of 37 bp with 13 bp of symmetry in each half-site. This structure also contains the transcription termination signal for the open reading frame that lies upstream from gdhA, making this a very complex structure.

The point mutants and even the deletion mutants retain a slight ability to respond to the presence of NAC. If the NAC-DNA complexes at the two sites normally interact in some way (e.g., to form a complex), then it would not be surprising that a kind of “induced fit” might stabilize an NAC-DNA complex that would be too weak to detect in the absence of the other complex. Moreover, we have previously found that many mutations in the NAC binding consensus sequence have only partial loss of function (21, 22), suggesting that the NAC binding site is quite robust and can tolerate considerable change and still retain some ability to bind NAC.

Further evidence for interaction between the two NAC:DNA sites comes from a recently isolated “negative control” (NC) mutant of NAC. This NACNC mutant can activate transcription at both the hut and ure promoters, but cannot mediate the strong repression at gdhAp in vivo. However, this mutant can bind to both upstream and downstream gdhA NAC sites in vitro (B. K. Janes, C. J. Rosario, and R. A. Bender, unpublished data). The NACNC mutant does not show the strong repression of gdhAp that results from the interaction of NAC bound to both NAC sites at gdhAp; however, it still causes the weak repression of gdhAp. This confirms that NACNC can bind to at least the upstream site in vivo and is consistent with the model that NACNC lacks some function in gdhAp repression other than occupancy of the two NAC sites.

NAC is largely dimeric in solution (6), and its 26-bp footprint at the activated promoters hutUp and ureDp is consistent with the presence of a dimer (6). However most LysR family members are tetramers in solution and bind as tetramers at their sites of action, often generating an extended footprint of 50 or more bp (24). Thus, there may well be information within the NAC structure that allows it to form tetramers under some conditions. The extended footprints made by NAC at the nac promoter (5) and at the downstream site in the gdhA promoter (Fig. 2B) resemble the footprints made by the tetrameric LysR family members, even having hypersensitive sites in the middle. Thus, NAC may indeed bind as a tetramer (a dimer of dimers) under some conditions, perhaps under the influence of the precise DNA sequence to which it binds. This dependence on the DNA sequence would be consistent with our earlier observation that the binding of the symmetric NAC homodimer to the asymmetric DNA site in hutUp results in an asymmetric complex capable of activating transcription from only one side of the bound NAC molecule (22).

The NAC binding sites at gdhA differ in sequence from those defined as “activating sites,” such as that seen at the hut promoter. In particular, the G in the ATA-N9-GAT motif, seen at gdhAp as well as in the autorepressing site in the nac promoter, may be significant. When the ATA-N9-TAT at hut was mutagenized to ATA-N9-GAT, not only was activation lost, but the binding of NAC to the site was weakened (22). However, the binding of NAC to the sites at gdhA is stronger than the binding of NAC to the site at hut (M. Raffin and R. A. Bender, unpublished observation). We know very little about the sequence requirements for NAC binding or action at these repressing sites, but clearly there must be other nucleotides in the site that alter the context of that G to make it significant for binding.

The gdhA promoter is unusual not only for its complex regulation (two-site repression and predicted positive regulator), but also for its core structure. The gdhA promoters from E. coli, S. enterica serovars Typhimurium and Paratyphi, and K. pneumoniae all have the extended −10 regions found in many promoters that lack a functional −35 region (12). The K. aerogenes gdhA promoter has not only one, but two possible −35 regions with sequences of TTGCTT and TTGCCT; however, the former is 19 bp from the −10 region, and the latter is 15 bp from it. The gdh-3 mutation has been repeatedly isolated. This mutation destroys the extended −10 region and creates a new −10 region with a 16-bp spacing from the more distant −35 region (11). This mutant has much higher expression of gdhAp, suggesting that the more distant −35 region can be functional, at least in the mutant. The lack of a good −35 region at an appropriate distance from the original −10 region may explain the need for the extended −10 region and upstream sequences to activate the gdhA promoter. In any event, there is much about the nature of the unrepressed level of gdhAp expression that we do not understand.

NAC is responsible for regulating a large number of operons in K. aerogenes, all involved in nitrogen metabolism. NAC is also present in E. coli, where it also regulates a large number of operons (18, 28), including a weak repression of GDH and a strong repression of GOGAT (7). However, the related bacterium Salmonella enterica lacks a nac gene (2, 18). An analysis of the genetic map in the nac regions of E. coli, S. enterica, and K. aerogenes and the nac-1 mutant of K. aerogenes suggests an important role for asparaginyl tRNA sequences. The E. coli genome has four asparaginyl tRNA genes in this region, three of which are oriented in the same direction (asnV, asnU, and asnT in Fig. 1). K. aerogenes has only two asparaginyl tRNA genes, and the DNA sequence of the flanking regions suggests that the E. coli and K. aerogenes maps are largely homologous, if one assumes that K. aerogenes has lost the material between asnU and asnT, including asnW. That still leaves two asn genes in the region oriented in the same direction. A further deletion of the material between these two remaining asn genes in K. aerogenes appears to have resulted in the nac-1 mutation (Fig. 1). It is tempting to speculate that S. enterica lost its nac gene by a similar deletion between two asparaginyl tRNA genes (homologous to the asnV and asnU genes of E. coli). Clearly other events have occurred in this region during the evolution of these organisms, and these are less easily explained.

The recent release of the annotated genome of S. enterica includes a gene (SMT069 in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and STY0730 in S. enterica serovar Typhi) identified as an ortholog of nac from E. coli and K. aerogenes. The protein encoded by this gene is certainly a member of the LysR family, and its closest match by a standard BLAST search is indeed NAC, but this gene is not a nac homolog. In fact, the similarity of the S. enterica gene to K. aerogenes nac is not qualitatively different from the general similarity of unrelated members of the LysR family. For example, the nac gene from K. aerogenes is 25% identical in amino acid sequence to the oxyR gene from E. coli, which is not much different from the 30% identity between the S. enterica ortholog and K. aerogenes nac. In contrast, the nac proteins from K. aerogenes and E. coli are 80% identical. S. enterica and E. coli are generally considered more similar to each other than either is to K. aerogenes (e.g., the oxyR products from E. coli and S. enterica are 95% identical). It would be surprising to find an S. enterica gene that is less similar to its E. coli homolog (32%) than is the K. aerogenes gene (80%). Moreover, we have shown previously that S. enterica contains no gene that functions as a nac gene in vivo (2). And yet, when the K. aerogenes nac gene was transferred to S. enterica, nac activity appeared. And so, simply stated, S. enterica carries no gene of its own with nac function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM47156 from the National Institutes of Health to R.A.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender, R. A., P. M. Snyder, R. Bueno, M. Quinto, and B. Magasanik. 1983. Nitrogen regulation system of Klebsiella aerogenes: the nac gene. J. Bacteriol. 156:444-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best, E. A., and R. A. Bender. 1990. Cloning of the Klebsiella aerogenes nac gene, which encodes a factor required for nitrogen regulation of the histidine utilization (hut) operons in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 172:7043-7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churchward, G., D. Belin, and Y. Nagamine. 1984. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene 31:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries, G. E., C. K. Raymond, and R. A. Ludwig. 1984. Extension of bacteriophage λ host range: selection, cloning, and characterization of a constitutive λ receptor gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:6080-6084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng, J., T. J. Goss, R. A. Bender, and A. J. Ninfa. 1995. Repression of the Klebsiella aerogenes nac promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:5535-5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goss, T. J., and R. A. Bender. 1995. The nitrogen assimilation control protein, NAC, is a DNA binding transcription activator in Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 177:3546-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goss, T. J., A. Perez-Matos, and R. A. Bender. 2001. Roles of glutamate synthase, gltDB, and gltF in nitrogen metabolism of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:6607-6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grove, C. L., and R. P. Gunsalus. 1987. Regulation of the aroH operon of Escherichia coli by the tryptophan repressor. J. Bacteriol. 169:2158-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helling, R. B. 1994. Why does Escherichia coli have two primary pathways for synthesis of glutamate? J. Bacteriol. 176:4664-4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janes, B. K., and R. A. Bender. 1998. Alanine catabolism in Klebsiella aerogenes: molecular characterization of the dadAB operon and its regulation by the nitrogen assimilation control protein. J. Bacteriol. 180:563-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janes, B. K., P. J. Pomposiello, A. Perez-Matos, D. J. Najarian, T. J. Goss, and R. A. Bender. 2001. Growth inhibition caused by overexpression of the structural gene for glutamate dehydrogenase (gdhA) from Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:2709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keilty, S., and M. Rosenberg. 1987. Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6389-6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, H.-P. P., and H. C. Reeves. 1994. In vivo phosphorylation of NADP+ glutamate dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli. Curr. Microbiol. 28:63-65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macaluso, A., E. A. Best, and R. A. Bender. 1990. Role of the nac gene product on the nitrogen regulation of some NTR-regulated operons of Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 172:7249-7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Meers, J. L., D. W. Tempest, and C. M. Brown. 1970. ′Glutamine-(amide):2-oxoglutarate amino transferase oxido-reductase (NADP)' an enzyme involved in the synthesis of glutamate by some bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 64:187-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, R. E., and E. R. Stadtman. 1972. Glutamate synthase from Escherichia coli: an iron-sulfide flavoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 247:7407-7419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muse, W. B., and R. A. Bender. 1998. The nac (nitrogen assimilation control) gene from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:1166-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muse, W. B., and R. A. Bender. 1999. The amino-terminal 100 residues of the nitrogen assimilation control protein (NAC) encode all known properties of NAC from Klebsiella aerogenes and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:934-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrow, K. S., T. J. Silhavy, and S. Garrett. 1986. cis-Acting sites required for osmoregulation of ompF expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 168:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Matos, A. E. 1999. Ph.D. thesis. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- 22.Pomposiello, P. J., B. K. Janes, and R. A. Bender. 1998. Two roles for the DNA recognition site of the Klebsiella aerogenes nitrogen assimilation control protein. J. Bacteriol. 180:578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell, B. S., D. L. Court, Y. Nakamura, M. P. Rivas, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 1994. Rapid confirmation of single copy lambda prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:5765-5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwacha, A., and R. A. Bender. 1993. The nac (nitrogen assimilation control) gene from Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 175:2107-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwacha, A., and R. A. Bender. 1993. The product of the Klebsiella aerogenes nac (nitrogen assimilation control) gene is sufficient for activation of the hut operons and repression of the gdh operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:2116-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmer, D. P., E. Soupene, H. L. Lee, V. F. Wendisch, A. B. Khodursky, B. J. Peter, R. A. Bender, and S. Kustu. 2000. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14674-14679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]