Abstract

The tmoABCDEF genes encode the toluene-4-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. Upstream from the tmoA gene an open reading frame, tmoX, encoding a protein 83% identical to TodX (todX being the initial gene in the todXFC1C2BADEGIH operon from Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E) was found. The tmoX gene is also the initial gene in the tmoXABCDEF gene cluster. The transcription initiation point from the tmoX promoter was mapped, and the sequence upstream revealed striking identity with the promoter of the tod operon of P. putida. The tod operon is regulated by a two-component signal transduction system encoded by the todST genes. Two novel genes from P. mendocina KR1, tmoST, were rescued by complementation of a P. putida DOT-T1E todST knockout mutant, whose gene products shared about 85% identity with TodS-TodT. We show that transcription from PtmoX and PtodX can be mediated by TmoS-TmoT or TodS-TodT, in the presence of toluene, revealing cross-regulation between these two catabolic pathways.

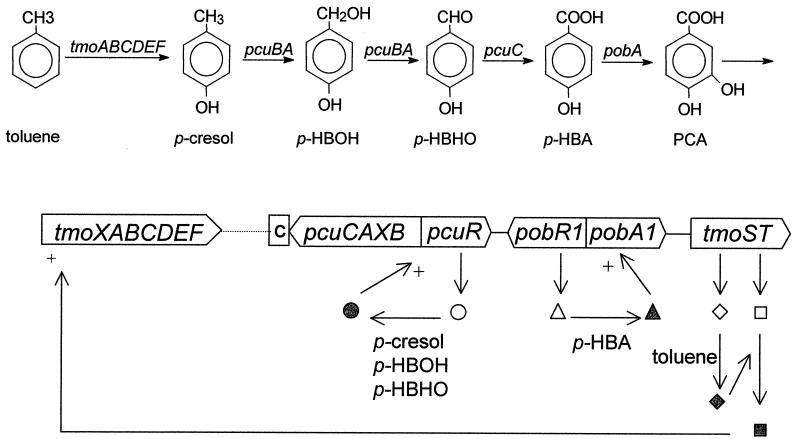

The first step in the metabolism of toluene in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 is carried out by toluene-4-monooxygenase (T4MO), encoded by the tmoABCDEF gene cluster (38, 39), which is responsible for the oxidation of toluene to p-cresol (35, 36). Two other independently regulated gene clusters are known to be required for the metabolism of toluene in P. mendocina KR1 (37). One encodes p-cresol methylhydroxylase and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase, which catalyze the successive oxidation of the methyl group of p-cresol to the corresponding acid, p-hydroxybenzoate; the other encodes p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase for forming protocatechuate, which is channeled to the β-ketoadipate route through an ortho-cleavage pathway (12). Although T4MO activity is known to be inducible by toluene, chlorinated solvents, and alkanes (6, 19), no information regarding the regulators involved in the expression of the tmo genes was available when this work was envisaged. To learn about the transcriptional control of the tmo genes, we first sequenced the region upstream of the tmoABCDEF genes in pMC4 (2) by the dideoxy sequencing method with the ABI Prism dRhodamine terminator kit (Applied Biosystems). A 1,362-nucleotide-long open reading frame 27 bp upstream of tmoA was found, whose deduced amino acid sequence shared significant homology with outer membrane proteins encoded in different toluene degradation operons from a number of gram-negative bacteria that use toluene as the sole C source (i.e., 83% identity with TodX of Pseudomonas putida F1 [34] and DOT-T1E [23] and 48% identity with TbuX of Ralstonia pickettii [13]). The initial gene in the tmo cluster was called tmoX.

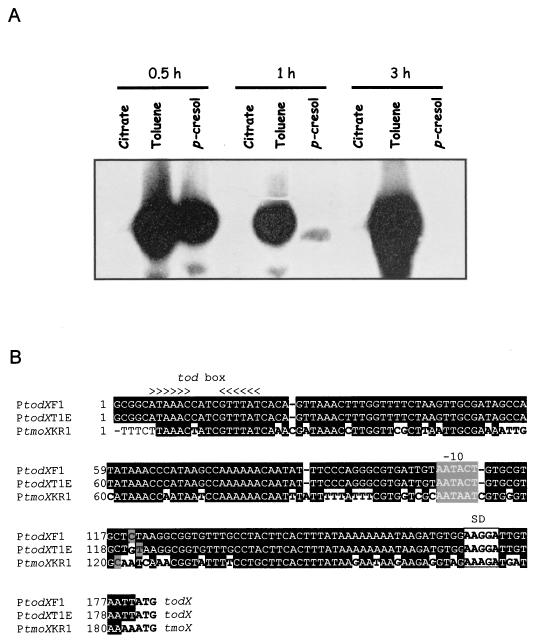

Identification of the transcription initiation point of the tmoX promoter and time course induction in response to different effectors.

To analyze the expression of the tmo genes, total RNA was isolated from P. mendocina KR1 grown on citrate in the presence and in the absence of toluene or p-cresol, the substrate and the hydroxylated product of the T4MO, respectively. A 23-mer oligonucleotide (5′-CGGTACTTACTATATCCGGCCCG-3′) complementary to tmoX mRNA was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP, and T4 polynucleotide kinase was used for primer extension analysis (33). About 105 cpm of the 5′-end-labeled primer was hybridized to 20 μg of total RNA, and primer extensions were done with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase as described previously (22). Results are shown in Fig. 1. The basal expression from tmoX was negligible in cells growing on citrate (Fig. 1A), and the level of expression increased about 20-fold in response to toluene supplied in the gas phase 30 min after exposure to the compound; thereafter, the expression level was maintained. With p-cresol as an effector, a high level of expression was found 30 min after addition; from then on the signal decreased significantly, due to exhaustion of p-cresol in the culture medium (data not shown). Similar results as those described above were observed when cells were grown with glucose as the carbon source instead of citrate (data not shown). These results suggested that glucose does not exert any kind of catabolite repression on tmoX gene expression, unlike other catabolic pathways for the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons that are subject to carbon control (4, 18, 29, 30). The cDNA product resulting from primer extension was 289 bases long, which allowed us to map the transcription initiation point from the tmoX gene at a C located 63 bp upstream from the A of the ATG start codon (Fig. 1B). The sequence around −10 resembled that of the −10 regions recognized by RNA polymerase with sigma-70, yet no region with similarity to a −35 box was recognized. Instead, between −24 and −45 the PtmoX promoter sequence is rich in A's, which may be related to the flexibility of this DNA segment (24). Further upstream, PtmoX exhibits a pseudopalindrome located at −100 to −113. Strikingly, this segment was found to be almost identical to the Tod box where TodT binds in the PtodX promoter (16), although the pseudopalindrome in PtmoX is 1 nucleotide shorter. In fact, the tmoX and todX promoter regions were found to be highly similar (Fig. 1B shows the alignment among the todX promoter regions of P. putida F1 and DOT-T1E strains and the P. mendocina KR1 tmoX promoter). The major difference between the promoters was at positions −24 to −30, where the tmoX promoter showed a T-rich region, whereas the the todX promoter presented CG-rich positions.

FIG. 1.

Identification and sequence characteristics of the P. mendocina tmoX promoter. (A) Time course transcription induction from the tmoX promoter. P. mendocina KR1 cells were grown on 10 mM citrate-supplemented M9 minimal medium at 30°C up to a turbidity at 660 nm of 0.8. The culture was split into nine aliquots of 20 ml. Three of them were kept as a control without any additions. A 1 mM concentration of p-cresol was added to three others, and toluene was supplied via the gas phase to the last three aliquots. Each sample was used to extract total RNA 30, 60, and 180 min after the effector was added, and primer extension was carried out as described previously (33). (B) Alignment of todX and tmoX promoters. The alignment was carried out with the Clustal W 1.8 computer program at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center. The transcription initiation point is indicated by gray-boxed black letters, the −10 region is in gray-boxed white letters, and Shine-Dalgarno sequences (27) are in white-boxed black letters. The first ATG is shown at the end of the sequences, and the pseudopalindromic tod boxes are indicated with arrowheads. Identities are shown by black-boxed white letters.

Isolation and characterization of P. mendocina KR1 tmoST genes.

The similarities between the tmoX and todX promoters prompted us to hypothesize that the expression from PtmoX could be mediated by a set of regulators similar to the TodS-TodT two-component system that controls expression from PtodX (16, 23). In a first approach, the todST genes of P. putida DOT-T1E in pMIR66 were used as a probe against P. mendocina KR1 and P. putida KT2440 chromosomal DNA. In Southern hybridization assays under low-stringency conditions (50°C without formamide), we found a 5-kb HindIII fragment of P. mendocina that hybridized with the todST probe, whereas with P. putida KT2440 no hybridization band was found (data not shown). We reasoned that the P. mendocina genes homologous to todST could complement a P. putida todST mutant unable to grow on toluene as the sole C source. This mutant was generated by gene replacement of the wild-type todST genes in the chromosome of P. putida DOT-T1E for the todS′::Km::′todT mutation contained in pT1-ST1Km (Table 1) via homologous recombination (26). To test the above hypothesis, we constructed a P. mendocina KR1 gene bank in the pLAFR3 cosmid vector (11, 26). The gene bank was mobilized to the DOT-T1E todST mutant, and a transconjugant able to grow on toluene and resistant to tetracycline was selected. The cosmid isolated from the transconjugant, called pMIR51, showed a 5-kb HindIII hybridization band against the todS and todT gene probes. The 5-kb HindIII fragment was subcloned in pBBR1MCS-5 to generate pMAX47-2. Two open reading frames whose translated products yielded a 973- and a 220-amino-acid-long polypeptide, respectively, were found. Their translated sequences were compared with all the entries in the nonredundant database as described in the BLAST program (1). The proteins showed the highest identity with TodS and TodT, a two-component signal transduction system of distinct P. putida strains (83 and 85% identity, respectively) (accession no. AF180147, Y18245, and U72354). Henceforth, the genes cloned in pMAX47-2 will be called tmoS and tmoT. This plasmid was transferred to the P. putida DOT-T1E todST mutant, which reacquired the ability to grow on toluene as the sole C source. Consequently, based on function and sequence, the P. mendocina KR1 TmoS and TmoT regulators belong to the family of two-component regulatory systems and are able to replace TodS and TodT in activating the tod operon.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains or plasmids used in this studya

| Bacterial strain or plasmid(s) | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. putida DOT-T1E | Prototroph, Tol+ (tod pathway) | 25 |

| P. putida KT2440 | Prototroph, Tol− | 10 |

| P. mendocina KR1 | Prototroph, Tol+ (tmo pathway) | 35 |

| P. putida DOT-T1E todST | DOT-T1E todST-minus derivative, Tol− | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | GmroriTRK2 | 15 |

| pHP45Ω-Km | Kmr Apr Ω/Km interposon | 8 |

| pKNG101 | SmrmobRK2 oriR6K sacBR | 14 |

| pLAFR3 | Tcr, derivative from pLAFR1 cosmid modified to include MCS and the Plac promoter fused to the lac α fragment | 11 |

| pMAX47-2 | Gmr, 5-kb HindIII fragment of pMIR51 containing tmoST genes inserted in pBBR1MCS-5 | This study |

| pMC4 | Smr, P. mendocina KR1 tmo-pcu gene cluster cloned at HindIII/BamHI site in pGV1120 | A. A. Gatenby |

| pMIR32 | Apr, 7.5-kb BamHI fragment of pMC4 containing tmoXABCDEF genes inserted in pUC19 | This study |

| pMIR36 | Apr, 1.2-kb BamHI/ApaLI fragment of pMIR32 containing tmoX promoter inserted at BamHI/HindIII site of pUC19 | This study |

| pMIR38 | TcroriRK2 PtmoX::′lacZ as 0.8-kb KpnI/PstI fragment of pMIR36 inserted in pMP220 | This study |

| pMIR51 | Tcr, chimeric cosmid of P. mendocina KR1 library bearing the tmoST genes | This study |

| pMIR66 | Gmr, 4-kb HindIII/BamHI fragment of pT1-155 containing the todST genes inserted in pBBR1MCS-5 | This study |

| pMIR70 | Apr, 352-bp-length PCR amplification product containing the todX promoter cloned in pGEM-T | This study |

| pMIR77 | TcroriRK2 PtodX::′lacZ as 0.4-kb EcoRI/PstI insert of pMIR70 inserted in pMP220 | This study |

| pMP220 | Tcr ′lacZ oriRK2 | 28 |

| pT1-125 | Apr, ∼16-kb BamHI fragment containing the tod operon inserted in pUC18 | 23 |

| pT1-155 | Apr, 4.3-kb XhoI/HindIII fragment of pT1-125 containing the todST genes inserted at SalI/HindIII site of pUC18 | This study |

| pT1-155STKm | Apr Kmr, deletion of 2.7-kb HpaI/EcoRV fragment of pT1-155 and insertion of Ω/Km cassette from pHP45Ω-Km | This study |

| pT1-ST1Km | Smr KmrtodS′::Km::′todT as 3.8-kb BamHI fragment of T1-155STKm inserted in pKNG101 | This study |

| pUC18, pUC19 | Apr, MCS, Plac fused to the α peptide of lacZ | 32 |

Tol+ Tol−, growth in toluene as the sole C source and unable to grow in toluene, respectively. Antibiotics were supplied at the indicated concentrations (micrograms per milliliter): ampicillin (Ap), 100; chloramphenicol (Cm), 30; gentamicin (Gm), 10 for Escherichia coli and 100 for Pseudomonas sp. strains; kanamycin (Km), 25; streptomycin (Sm), 50; and tetracycline (Tc), 10. E. coli strains were usually grown at 37°C in LB medium, whereas Pseudomonas sp. strains were grown at 30°C in LB medium or in M9 minimal medium with glucose (25 mM) or citrate (10 mM) as the C source, as previously described (23). MCS, multiple cloning site.

Expression of the transcriptional fusions PtmoX::′lacZ and PtodX::′lacZ in Pseudomonas.

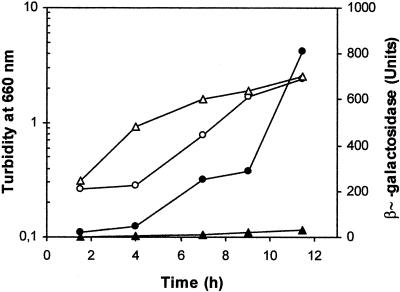

Transcriptional fusions of the tmoX and todX promoters were constructed by using the wide-range pMP220 reporter plasmid based on ′lacZ (28). For the generation of PtmoX::′lacZ, the 0.8-kb KpnI-PstI fragment of pMIR36 containing the tmoX promoter was fused to ′lacZ, yielding plasmid pMIR38. This plasmid was introduced by electrotransformation (7) into different Pseudomonas sp. hosts to study the expression of the tmoX promoter in different genetic backgrounds, i.e., P. mendocina KR1 (tmoST+), P. putida DOT-T1E (todST+), and hosts deficient in both TmoS-TmoT and TodS-TodT such as P. putida KT2440 and P. putida DOT-T1E todST. β-Galactosidase activities were measured in P. mendocina KR1 cells growing in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium in the absence and in the presence of toluene. We found that throughout the growth curve the expression level from the PtmoX promoter was negligible in the absence of toluene (Fig. 2); in contrast in the presence of the aromatic hydrocarbon β-galactosidase activity increased steadily up to 800 U after 12 h of incubation (Fig. 2). The delay of about 4 h observed in the induction could be a consequence of several circumstances, e.g., the limiting amount of regulators under these experimental conditions, since the delay was shortened as the regulators were supplied in pMAX47-2 (data not shown). As expected, no activity was reported from the tmoX promoter in P. putida KT2440 and the P. putida todST mutant strain, since these strains lack a homologue to the todST and tmoST genes (data not shown). As mentioned above, plasmid pMAX47-2 bearing the tmoST genes was able to confer the ability to grow on toluene on the P. putida DOT-T1E todST mutant strain. We therefore expected this plasmid to restore inducibility from the PtmoX promoter. To test this hypothesis, β-galactosidase activity was determined in P. putida DOT-T1E todST(pMIR38)(pMAX-47-2) both in the absence and in the presence of toluene. High levels of β-galactosidase activity were detected (>5,000 U in the exponential growth phase) with toluene (Table 2). Similar results were obtained with P. putida KT2440 as the host for plasmids pMIR38 and pMAX47-2.

FIG. 2.

Expression from the tmoX promoter in P. mendocina KR1. Bacteria cells were electrotransformed with plasmid pMIR38 (PtmoX::′lacZ). P. mendocina KR1(pMIR38) was grown overnight on LB medium supplied with tetracycline, and cells were diluted 100-fold in the same medium with toluene in the gas phase (circles) or without toluene (triangles). Growth was determined as turbidity of the culture (open symbols), and specific β-galactosidase activities (Miller units) (solid symbols) were monitored (21). Cells had been permeabilized with mixed alkyltrimethylammonium bromide at 4°C for 20 min before the β-galactosidase assays were done. Experiments were repeated with three cultures, and results from a typical experiment from a single culture are presented.

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activities expressed from PtmoX::′lacZ and PtodX::′lacZ in P. mendocina KR1 and P. putida strainsa

| Strain | Plasmid(s) | β-Gal activity (Miller units)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB

|

M9 + glucose

|

||||

| − Toluene | + Toluene | − Toluene | + Toluene | ||

| KR1 | pMIR38 | 1 | 600 | 1 | 1,330 |

| DOT-T1E | pMIR77 | ND | ND | 1 | 590 |

| DOT-T1E todST | pMIR38, pMAX47-2 | 5 | 5,350 | 2 | 2,550 |

| DOT-T1E todST | pMIR38, pMIR66 | 4 | 4,110 | 4 | 3,880 |

| DOT-T1E todST | pMIR77, pMAX47-2 | 4 | 4,710 | 3 | 2,600 |

| DOT-T1E todST | pMIR77, pMIR66 | 4 | 4,550 | 2 | 2,250 |

Plasmids pMIR38 and pMIR77 contain the PtmoX::′lacZ and PtodX::′lacZ transcriptional fusions, respectively; while plasmids pMAX47-2 and pMIR66 encode the TmoS-TmoT and TodS-TodT proteins, respectively. Cultures were grown to the mid-exponential growth phase on LB or minimal M9 medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose without toluene or with 3 mM toluene. β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activity was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Strains KR1 and DOT-T1E bearing the vector plasmids pMP220 and pBBR1MCS-5 showed no activity; strain DOT-T1E todST showed no activity with plasmid pMIR38 or pMIR77, as expected. ND, not determined.

We also tested whether the todST genes induced expression from PtmoX. This assay was done with the P. putida DOT-T1E todST mutant strain bearing pMIR38 and pMIR66. As above, β-galactosidase activity was high when the cells were grown in the presence of toluene, with levels above 4,000 U, whereas in the absence of the aromatic hydrocarbon the activity was negligible. The assays that we reported were also done with the same strains grown on M9 minimal medium with glucose as the C source, both in the absence and in the presence of toluene. In the presence of toluene, the level of β-galactosidase from the PtmoX::′lacZ promoter increased almost 1,000-fold (Table 2), while in the absence of the effector expression was negligible. The above results clearly show that expression from PtmoX can be efficiently induced by either the TmoS-TmoT or the TodS-TodT pair of regulators.

To generate the PtodX::′lacZ fusion, the promoter region was amplified by PCR with plasmid pT1-4 as a template (23) and the following two primers: 5′-CGGAATTCGGTCTGAGGTTTTCATCGAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCAATTACAATCCTTCCACATCTTA-3′. The 352-bp PCR product was cloned in pGEM-T (Promega) to produce pMIR70. The EcoRI-PstI fragment containing the todX promoter was fused to ′lacZ at the same sites in the polylinker of pMP220, resulting in plasmid pMIR77. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in P. putida DOT-T1E(pMIR77) growing on M9 minimal medium with glucose as the C source in both the presence and the absence of toluene, as described above. In the absence of toluene, the expression level from the PtodX promoter was insignificant, but in its presence activity was almost 600 U. As expected, in the P. putida DOT-T1E todST(pMIR77) mutant strain expression from PtodX was negligible (data not shown); however, when the strain was transformed with pMIR66 the expression from PtodX was significantly enhanced in response to the presence of toluene (Table 2). The induction level was about 1,000-fold both in LB rich medium and in M9 minimal medium. Results similar to those reported above were found in this host background when the tmoST genes in plasmid pMAX47-2 were the regulators instead of the todST genes (Table 2). Therefore, this result also indicates that the PtodX promoter can be induced by the regulators TmoS-TmoT of the T4MO pathway besides its own set of regulators, TodS-TodT.

Cross-regulation in catabolic pathways for aromatic compounds.

The above set of results established a case of cross-activation in the two-component signal transduction system that controls the expression of two different catabolic pathways for toluene metabolism. These results can be interpreted as evidence that the same regulatory system was recruited independently to control two different catabolic pathways for the aerobic degradation of toluene. In Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2 the pathway for styrene degradation is under the control of the StyS and StyR proteins (31), which are 85% identical to the TodS and TodT-TmoS and TmoT proteins. Given that TodS also recognizes styrene as an effector and that, upon activation of the TodT protein by TodS with styrene, transcription from the PtodX promoter takes place (23), it seems that this kind of regulator has been recruited on several occasions to control different catabolic pathways. Although this work is, to our knowledge, the first communication of two-component system-based regulators that are interchangeable in the control of catabolic pathways for hydrocarbon degradation, it should be mentioned that Lehay et al. (17) demonstrated cross-regulation of TmbR and TbuT with the benzene monooxygenase and toluene-2-monooxygenase operons from two Burkholderia species. Along the same lines, Fernández et al. (9) demonstrated cross-activation of the xylene monooxygenase and phenol hydroxylase pathways of P. putida by the XylR and DmpR regulators. In the two latter cases, the corresponding regulators belong to the NtrC family of positive transcriptional regulators (3). Therefore, it seems that the same sets of regulators have been recruited several times to control different catabolic pathways, perhaps because the diversity required for the regulators to perform their functions was less strict.

pcu/pobA and tmoST genes form a cluster in P. mendocina KR1.

The oxidation of toluene to Krebs cycle intermediates in P. putida DOT-T1E and F1 by the Tod pathway is effected by a set of enzymes all of which are expressed as a single transcriptional unit, as surmised from the fact that the genes that encode toluene dioxygenase and the subsequent meta-cleavage of 3-methylcatechol are linked (16, 20, 23). The todST genes are found 212 nucleotides downstream of the catabolic operon. These genes encode the regulators (20, 23), indicating that the catabolic and regulatory operons are closely clustered. In contrast, in P. mendocina KR1 the tmoST genes are not located in the vicinity of the tmoXABCDEF gene cluster encoding T4MO that oxidizes toluene into p-cresol. The metabolism of p-cresol in P. mendocina requires at least two gene clusters: the pcu gene products, responsible for the oxidation of p-cresol into p-hydroxybenzoate (Fig. 3), and the pobA and pobR genes, the former encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase and the latter encoding its regulator (2). When we analyzed the DNA sequences surrounding tmoST (Fig. 3), we found that the pobA1R1 genes were adjacent to tmoST. The ATG start codon of tmoS and the stop codon of pobA1 are separated by 714 bp. The pobR1 and pobA1 genes are transcribed divergently, as in Acinetobacter species (5), and the pcu genes for the utilization of p-cresol are flanking pobR1. The pcu gene cluster contains five genes, pcuR and pcuCAXB (2). pcuR encodes the regulator of the pcuCBXA genes (M. Olson and A. A. Gatenby, unpublished results). Therefore, it seems that to date the metabolism of toluene to protocatechuate in P. mendocina KR1 involves two sets of clusters, tmoXABCDEF on the one hand and pcu, pobRA, and tmoST on the other. The nature of the gene products in the region between the tmo and the pcu genes is unknown at present.

FIG. 3.

Oxidation of toluene to protocatechuate by P. mendocina KR1 and scheme of the cluster of tmo/pcu/pob genes needed for this biotransformation in this strain. tmoXABCDEF, T4MO genes; c, putative cytochrome c gene; pcuRCAXB, p-cresol utilization genes; pobR1 and pobA1, regulator and p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase, respectively; tmoST, two-component signal transduction system; p-HBOH, p-hydroxybenzylalcohol; p-HBHO, p-hydroxybenzylaldehyde; p-HBA, p-hydroxybenzoate; PCA, protocatechuate.

In short, we show that transcription of the PtmoX promoter that directs the synthesis of the tmoXABCDEF gene cluster for T4MO is induced by a two-component system made up of TmoS and TmoT, homologous to TodS and TodT, respectively. The tmoS and tmoT genes are not linked to the tmoXABCDEF genes but to a set of genes required for the metabolism of p-cresol, the product resulting from toluene oxidation by T4MO.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The nucleotide sequence of the tmoX gene was deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AF506285. The sequence of the pMAX47-2 insert was deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AY052500.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the DuPont Company.

We thank Cathy Kalbach from DuPont for isolating the tmo operon and Sima Sariaslani and Arie Ben-Bassat from DuPont and Nick Ornston from Yale University for stimulating discussions and suggestions. We also thank Ana Hurtado for DNA sequencing, Carmen Lorente and M. Mar Fandila for secretarial assistance, and Karen Shashok for improving the language.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Bassat, A., M. Cattermole, A. A. Gatenby, K. J. Gibson, M. I. Ramos-González, J. L. Ramos, and S. Sariaslani. June2001. Method for the production of p-hydroxybenzoate in species of Pseudomonas and Agrobacterium. PCT application WO 01/92539.

- 3.Buck, M., M. T. Gallegos, D. J. Studholme, Y. Guo, and J. D. Gralla. 2000. The bacterial enhancer-dependent σ54 (σN) transcriptional factor. J. Bacteriol. 182:4129-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cases, I., F. Velázquez, and V. de Lorenzo. 2001. Role of ptso in carbon-mediated inhibition of the Pu promoter belonging to the pWW0 Pseudomonas putida plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 183:5128-5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMarco, A. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. Regulation of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase synthesis by PobR bound to an operator in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 176:4277-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duetz, W. A., C. de Jong, P. A. Williams, and J. G. van Andel. 1994. Competition in chemostat culture between Pseudomonas strains that use different pathways for the degradation of toluene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2858-2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enderle, P. J., and M. A. Farwell. 1998. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. BioTechniques 25:954-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellay, R., J. Frey, and H. Krisch. 1987. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 52:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández, S., V. Shingler, and V. de Lorenzo. 1994. Cross-regulation by XylR and DmpR activators of Pseudomonas putida suggests that transcriptional control of biodegradative operons evolves independently of catabolic genes. J. Bacteriol. 176:5052-5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin, F. C. H., M. Bagdasarian, M. M. Bagdasarian, and K. N. Timmis. 1981. Molecular and functional analysis of the TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida and cloning of the genes for the entire regulated aromatic ring meta cleavage pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:7458-7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman, A. M., S. R. Long, S. E. Brown, W. J. Buikema, and F. M. Ausubel. 1982. Construction of a broad host range cosmid cloning vector and its use in the genetic analysis of Rhizobium mutants. Gene 18:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahng, H.-Y., A. M. Byrne, R. H. Olsen, and J. J. Kukor. 2000. Characterization and role of tbuX in utilization of toluene by Ralstonia pickettii PKO1. J. Bacteriol. 182:1232-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaniga, K., I. Delor, and G. R. Cornelis. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau, P. C. K., Y. Wang, A. Patel, D. Labbé, H. Bergeron, R. Brousseau, Y. Konishi, and M. Rawlings. 1997. A bacterial basic region leucine zipper histidine kinase regulating toluene degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1453-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehay, J. G., G. R. Johnson, and R. H. Olsen. 1997. Cross-regulation of toluene monooxygenases by the transcriptional activators TmbR and TbuT. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3736-3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marqués, S., A. Holtel, K. N. Timmis, and J. L. Ramos. 1994. Transcription induction kinetics from the promoters of the catabolic pathway of TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida for metabolism of aromatics. J. Bacteriol. 176:2517-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClay, K., S. H. Streger, and R. J. Steffan. 1995. Induction of toluene oxidation activity in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 and Pseudomonas sp. strain ENVPC5 by chlorinated solvents and alkanes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3479-3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menn, F. M., G. J. Zylstra, and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Location and sequence of the todF gene encoding 2-hydroxy-6-oxohepta-2,4-dienoate hydrolase in Pseudomonas putida F1. Gene 104:91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Mosqueda, G., and J. L. Ramos. 2000. A set of genes encoding a second toluene efflux system in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E is linked to the tod genes for toluene metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 182:937-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosqueda, G., M. I. Ramos-González, and J. L. Ramos. 1999. Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1 strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene 232:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérez-Martín, J., and V. de Lorenzo. 1997. Clues and consequences of DNA bending in transcription. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:593-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, M. J. Huertas, and A. Haïdour. 1995. Isolation and expansion of the catabolic potential of a Pseudomonas putida strain able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Bacteriol. 177:3911-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos-González, M. I., and S. Molin. 1998. Cloning, sequencing, and phenotypic characterization of the rpoS gene from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 180:3421-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shine, J., and L. Dalgarno. 1974. The 3′-terminal sequence of E. coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:1342-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spaink, H., R. Okker, C. Wijffelman, E. Pees, and B. Lugtenberg. 1987. Promoters in the nodulation region of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1JI. Plant Mol. Biol. 9:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sze, C. C., L. M. D. Bernardo, and V. Shingler. 2002. Integration of global regulation of two aromatic-responsive σ54-dependent systems: a common phenotype by different mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 184:760-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sze, C. C., A. D. Laurie, and V. Shingler. 2001. In vivo and in vitro effects of integration host factors at the DmpR-regulated σ54-dependent promoter. J. Bacteriol. 183:2842-2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco, A., S. Alonso, J. L. García, J. Perera, and E. Díaz. 1998. Genetic and functional analysis of the styrene catabolic cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2. J. Bacteriol. 180:1063-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmid: an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vílchez, S., L. Molina, C. Ramos, and J. L. Ramos. 2000. Proline catabolism by Pseudomonas putida: cloning, characterization, and expression of the put genes in the presence of root exudates. J. Bacteriol. 182:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Y., M. Rawlings, D. T. Gibson, D. Labbé, H. Bergeron, R. Brousseau, and P. C. K. Lau. 1995. Identification of a membrane protein and truncated LysR-type regulator associated with the toluene degradation pathway in Pseudomonas putida F1. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:570-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whited, G. M., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Toluene-4-monooxygenase, a three-component enzyme system that catalyzes the oxidation of toluene to p-cresol in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. J. Bacteriol. 173:3010-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whited, G. M., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Separation and partial characterization of the enzymes of the toluene-4-monooxygenase pathway in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. J. Bacteriol. 173:3017-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright, A., and R. H. Olsen. 1994. Self-mobilization and organization of the genes encoding the toluene metabolic pathway of Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:235-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yen, K.-M., and M. R. Karl. 1992. Identification of a new gene, tmoF, in the Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 174:7253-7261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yen, K.-M., M. R. Karl, L. M. Blatt, M. J. Simon, R. B. Winter, P. R. Fausset, H. S. Lu, A. A. Harcourt, and K. K. Chen. 1991. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 173:5315-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]