Abstract

To elucidate phytochrome A (phyA) function in rice, we screened a large population of retrotransposon (Tos17) insertional mutants by polymerase chain reaction and isolated three independent phyA mutant lines. Sequencing of the Tos17 insertion sites confirmed that the Tos17s interrupted exons of PHYA genes in these mutant lines. Moreover, the phyA polypeptides were not immunochemically detectable in these phyA mutants. The seedlings of phyA mutants grown in continuous far-red light showed essentially the same phenotype as dark-grown seedlings, indicating the insensitivity of phyA mutants to far-red light. The etiolated seedlings of phyA mutants also were insensitive to a pulse of far-red light or very low fluence red light. In contrast, phyA mutants were morphologically indistinguishable from wild type under continuous red light. Therefore, rice phyA controls photomorphogenesis in two distinct modes of photoperception—far-red light–dependent high irradiance response and very low fluence response—and such function seems to be unique and restricted to the deetiolation process. Interestingly, continuous far-red light induced the expression of CAB and RBCS genes in rice phyA seedlings, suggesting the existence of a photoreceptor(s) other than phyA that can perceive continuous far-red light in the etiolated seedlings.

INTRODUCTION

Light is one of the most important environmental stimuli that plays a pivotal role in the regulation of plant growth, development, and metabolic activities. The perception of environmental light by plants is achieved by a family of plant photoreceptors that includes the phytochromes (Neff et al., 2000), cryptochromes, and several others (Briggs and Huala, 1999), which are capable of detecting a wide spectrum of light wavelengths ranging from UV to far-red light.

Physiological and photochemical studies in recent decades have shown that presumed phytochrome-mediated responses in plants can be classified into three different response modes: red (R)/far-red (FR) reversible responses designated the low fluence response (LFR) and two other responses named the very low fluence response (VLFR) and the high irradiance response (HIR) according to their energy requirements (Mohr, 1962; Briggs et al., 1984). In a typical LFR, plants respond to 1 to 1000 μmol m−2 of R light, whereas the VLFR requires only 0.1 to 1 μmol m−2 of R light. The HIR requires prolonged exposure to light of relatively high photon flux and shows fluence rate dependence. Action spectra for VLFR, LFR (Shinomura et al., 1996), and HIR (Shinomura et al., 2000) using phytochrome-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis showed that phyA is the principal photoreceptor involved in the VLFRs, such as induction of seed germination (Shinomura et al., 1996) and CAB gene expression (Hamazato et al., 1997), and the FR light–induced HIRs, including inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (Quail et al., 1995; Shinomura et al., 2000). On the other hand, phyB controls LFR in a R/FR reversible mode.

Phytochromes in higher plants are encoded by a small gene family that is composed of five members (PHYA to PHYE) in Arabidopsis (Sharrock and Quail, 1989; Clack et al., 1994). Within the PHY gene family, phytochrome A (phyA) has been studied most extensively for its molecular properties and physiological function (Furuya, 1993; Quail et al., 1995) to identify its specific role(s) in a number of phytochrome-mediated events leading to plant growth and development. The mode of photoperception by phyA seems to be common among higher plants, but the function of phyA in vivo could be somewhat distinctive in different plant species at different developmental stages. For example, pea phyA mutants grown under long day photoperiods show a highly pleiotropic phenotype in mature plants, including short internodes, thickened stems, delayed flowering and senescence, longer peduncles, and higher seed yield (Weller et al., 1997), whereas the Arabidopsis phyA mutants grown under white light are morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type plants (Nagatani et al., 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993).

Although phytochromes are the most extensively characterized photoreceptors in plants, their diverse functions in the regulation of plant development have been characterized mainly in dicots, and little information in this regard is available in monocots. Phytochrome genes were isolated in monocots long ago (oat PHYA, Hershey et al., 1985; maize PHYA, Christensen and Quail, 1989; rice PHYA, Kay et al., 1989; rice PHYB, Dehesh et al., 1991), but the in vivo functions have not been elucidated, mainly due to the unavailability of phytochrome mutants. To date, the only phytochrome mutant found in monocots was a phyB mutant of sorghum that was originally identified as a ma3R early-flowering allele (Childs et al., 1997). Very recently, a phytochrome chromophore-deficient mutant was identified in rice (Izawa et al., 2000).

Rice has served as a model monocot plant system in which to explore complex genetic and physiological phenomena because a wealth of information is available on its genomic structure and functionality (Shimamoto, 1995). The task of designing and executing complex genetic studies in rice has been further facilitated by the availability of discrete research materials and tools, such as the high density genetic linkage map and thousands of expressed sequence tag clones made available by the Rice Genome Research Program (Yamamoto and Sasaki, 1997). A recent addition to these tools is the development of a gene knockout system using a rice retrotransposon named Tos17 (Hirochika et al., 1996; Hirochika, 1997, 1999), which makes it possible to isolate mutants for genes of interest. In this system, the active Tos17 can be used to easily generate a large number of Tos17-tagged mutant lines, and the mutants of a specific gene can be identified from the large mutant population (mutant panels) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Tos17- and gene-specific primers.

The generation and characterization of phytochrome mutants of rice can broaden the existing view of phytochrome function in plants, especially in terms of the differences in phytochrome functionality in monocots and dicots. In this article, we report the isolation and characterization of a phyA mutant from a monocot (rice) plant. Because the mutant phenotype of rice deficient in phyA was unknown, we adapted the reverse genetics strategy to discover the rice phyA mutant. Physiological analyses of the phyA mutants at the young seedling stage revealed that phyA is responsible for the inhibition of coleoptile elongation that is produced by irradiation with a pulse of very low fluence R (VLF-R) light. Moreover, phyA also is involved in the inhibition of mesocotyl elongation and the induction of the gravitropic response in crown roots under continuous FR light. In contrast, phyA deficiency did not impart any noticeable morphological changes in plants grown under natural light conditions. The function of phyA in rice appears to be unique and restricted to the deetiolation process.

RESULTS

Isolation of Rice phyA Mutants from Mutant Panels

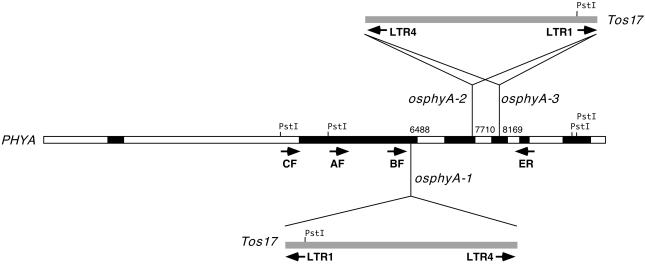

We screened a large population of Tos17 insertional mutants of rice by PCR to isolate rice phyA mutants. Three mutant panels were subjected to PCR-based screening using all combinations of four PHYA-specific (Figure 1) and two Tos17-specific primers. As a result, we identified three mutant lines, osphyA-1, osphyA-2, and osphyA-3, in which Tos17s were inserted into the PHYA genes. The amplified DNA fragments corresponding to the three identified lines were cloned and sequenced to determine the insertion sites and the orientation of transposed Tos17, and the results are summarized in Figure 1. Tos17 was found to be inserted in the forward orientation near the end of the second exon in line osphyA-1. In the two other lines, the insertion of Tos17 was detected in reverse orientation in the third (osphyA-2) or fourth exon (osphyA-3). In all three mutant lines, the transposon was inserted into the coding sequence of the PHYA genes and the predicted amino acid sequences were terminated prematurely. The results suggest that Tos17-tagged phyA alleles are functionally impaired.

Figure 1.

The Structure of the PHYA Gene and Insertion Sites of Tos17 in the PHYA Gene of Three Mutant Lines.

The structure of the PHYA gene is derived from sequence information available in the database (GenBank accession number X14172). The exon and intron regions of PHYA are presented as closed and open bars, respectively. Insertion sites of Tos17 sequences in the PHYA gene of three mutant lines are indicated by vertical bars labeled with the names of mutant lines and the range of nucleotides at the sites of insertion. The integrated Tos17 sequences are shown by shaded bars with insertion orientation. The locations of primers designed for PCR screening are indicated by arrows. PstI sites used for DNA gel blot analysis also are indicated.

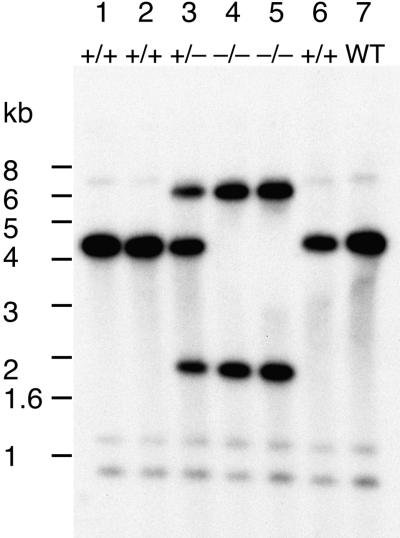

The insertion of Tos17 into the PHYA gene was further confirmed by DNA gel blot hybridization. The DNA was isolated from progeny plants of line osphyA-1 and hybridized with a cDNA clone of the PHYA gene to distinguish the genotypes of mutant and wild-type alleles. On the basis of the restriction map of PHYA (Figure 1), cutting with PstI should give two hybridizing bands (0.8 and 4.3 kb) for the wild-type alleles, whereas three bands (6.6, 1.8, and 0.8 kb) are supposed to be hybridized for the mutant alleles because the insertion of Tos17 adds one more PstI site. As expected, we observed three banding patterns in the progeny of the osphyA-1 line: (1) homozygous for the insertion (Figure 2, lanes 4 and 5); (2) heterozygous (Figure 2, lane 3); and (3) wild type (Figure 2, lanes 1, 2, and 6). Because the number of plants showing these genotypes follows the Mendelian ratio of 1:2:1, it was demonstrated that the mutant alleles were stably transmitted to the next generation according to Mendel's first law. We also confirmed the insertion of Tos17 into the PHYA gene and the normal inheritance of the mutant alleles in two other mutant lines, osphyA-2 and osphyA-3 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

DNA Gel Blot Analysis of Segregating Progeny of osphyA-1 Mutant Lines.

The DNA gel blot of PstI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with the complete sequence of PHYA cDNA. Typical autoradiogram profiles of wild type (Akitakomachi) and six progeny of the osphyA-1 line are shown. Hybridized bands of 4.3 kb are from plants with the wild-type allele, and those of 6.6 and 1.8 kb are from plants with the mutant allele. Therefore, lanes 4 and 5 are homozygous (−/−) for the insertion of Tos17, lane 3 is heterozygous (+/−) for the same insert, and lanes 1, 2, and 6 are homozygous for the wild type (WT; +/+).

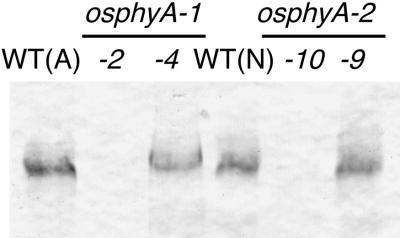

Immunochemical Analysis of the PHYA Apoprotein

The level of PHYA apoprotein in the insertional mutants was determined by immunoblotting to examine if the mutant alleles of PHYA were null mutations. Figure 3 shows that the PHYA apoprotein was undetectable in crude protein extracts from etiolated phyA mutant progeny (osphyA-1-2 and osphyA-2-10), whereas progeny with wild-type PHYA alleles (osphyA-1-4 and osphyA-2-9) had similar levels of PHYA as the wild-type plants (cvs Akitakomachi and Nipponbare). Thus, the PHYA gene appeared to be completely knocked out in the osphyA-1 and osphyA-2 mutant lines.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot Detection of PHYA Apoproteins in Dark-Grown Seedlings.

Seven-day-old etiolated seedlings of wild type (WT; Akitakomachi [A] and Nipponbare [N]) and segregating progeny of two phyA mutant lines (osphyA-1 and osphyA-2) were used for the extraction of crude protein. Two progeny (homozygous for the insertion, osphyA-1-2 and osphyA-2-10; and wild type, osphyA-1-4 and osphyA-2-9) were chosen for each mutant line. Each lane was loaded with 50 μg of total protein for the detection of PHYA by the monoclonal anti-rye PHYA antibody (mAR07).

Effect of Continuous FR Light on Growth Responses in phyA Mutants

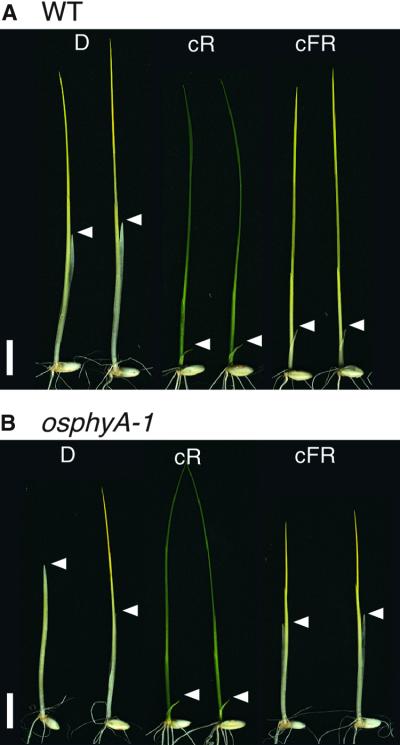

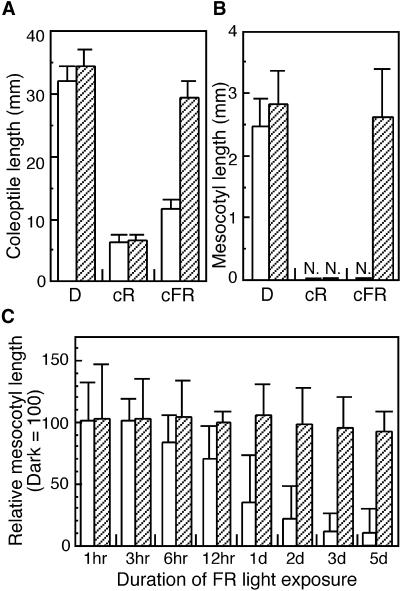

We examined the effect of continuous irradiation with R and FR light on the growth responses of young wild-type and osphyA-1 mutant seedlings. The results are presented as original photographs of seedlings (Figure 4) and as measurements of mean lengths of coleoptile and mesocotyl (Figures 5A and 5B). The coleoptiles and mesocotyls of the dark-grown seedlings reached their maximum lengths 6 days after the induction of germination without any additional changes for up to 19 days (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Phenotypic Comparison of Wild-Type (WT) and phyA Mutant Plants Grown under Different Light Conditions.

Seedlings of wild type (A) (Akitakomachi) and osphyA-1 mutants (B) were grown under complete darkness (D), continuous R light (cR), or continuous FR light (cFR) for 11 days. Two seedlings are shown for each treatment. White arrowheads indicate the tips of coleoptiles.  .

.

Figure 5.

Coleoptile and Mesocotyl Lengths of Wild Type and phyA Mutants Grown under Different Light Conditions.

(A) and (B) Wild-type (Akitakomachi; open bars) and osphyA-1 (hatched bars) seedlings were grown under continuous R light (cR), under continuous FR light (cFR), or in complete darkness (D) for 11 days. The lengths of coleoptiles (A) and mesocotyls (B) of these seedlings were measured individually.

(C) Effect of continuous FR light on the inhibition of the mesocotyl elongation of wild-type (Akitakomachi) and osphyA-1 seedlings. Two-day-old etiolated seedlings were irradiated with continuous FR light for intervals ranging from 1 hr to 5 days (d) and kept in darkness until 7th day. Their mesocotyl lengths were measured and the relative lengths compared with the dark control were shown. Error bars represent se; n  . N. indicates that the corresponding tissue was not detected.

. N. indicates that the corresponding tissue was not detected.

Both the wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings exhibited a typical elongation of coleoptiles and mesocotyls when grown in constant darkness (Figures 4 and 5D). The different appearance of the two dark-grown osphyA-1 seedlings in Figure 4 is due to a difference in the timing of germination. We did not observe significant difference of growth rate of the shoot between wild type and phyA mutants. A commonly observed inhibition of coleoptile and mesocotyl elongation also was apparent when the seedlings of wild type and osphyA-1 mutants were exposed to continuous R light for 11 days. In this experiment, exposure to continuous R light reduced the growth of coleoptiles to one-sixth of that in dark-grown seedlings in both wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings (Figures 4 and 5A, cR). Similarly, growth of the mesocotyl was inhibited completely under continuous R light in both lines (Figures 4 and 5B, cR). In contrast, growth responses of the osphyA-1 seedlings to continuous FR light were completely different from those of the wild type. When the seedlings were exposed to FR light for 11 days, the osphyA-1 coleoptiles and mesocotyls elongated like those of dark-grown seedlings (Figures 4B and 5, cFR), whereas wild-type coleoptiles were short (Figures 4A and 5A, cFR) and wild-type mesocotyls were undetectable (Figures 4A and 5B, cFR).

To determine the irradiation period with FR light needed for the detection of such growth inhibition, exposure times to FR light were gradually shortened until growth inhibition was no longer observed. Two-day-old etiolated seedlings, which are most sensitive to FR light for the inhibition of mesocotyl elongation, were exposed for various durations of continuous FR light from 1 hr to 5 days. After the irradiation, they were kept in darkness until the measurement of mesocotyl lengths in the 7th day. Their mesocotyl lengths were compared with those of seedlings grown in constant darkness as a control (Figure 5C). When the wild-type seedlings were exposed to continuous FR light for 3 hr or shorter, their mesocotyls were as long as those of seedlings grown in the dark (Figure 5C). However, when they were exposed for longer than 6 hr, their mesocotyl lengths became shorter as the duration of light exposure increased (Figure 5C). In contrast, the mesocotyl elongation of osphyA-1 mutants was not affected even by a 5-day exposure to continuous FR (Figure 5C). These results indicate that the inhibition of mesocotyl elongation is detectable in wild-type seedlings when exposed to a prolonged FR light irradiation (more than 6 hr). Essentially similar responses to continuous R and FR light were observed in another phyA mutant, osphyA-2 (data not shown). These results indicate that etiolated seedlings of the phyA mutants are insensitive to FR light for the modulation of coleoptile and mesocotyl length.

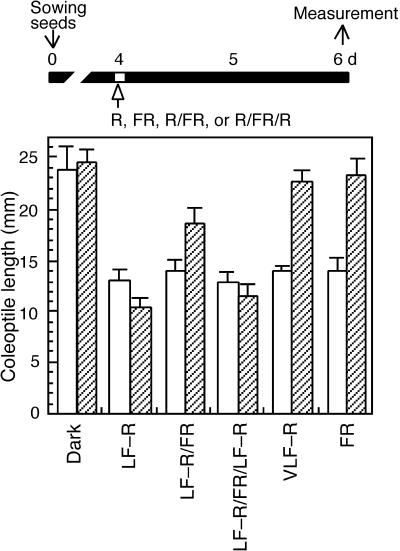

Effect of Light Pulse Irradiation on Coleoptile Growth

We examined the effect of R and FR light pulse irradiation with both low fluence (LF) and very low fluence (VLF) on the coleoptile growth of wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings. Etiolated seedlings with coleoptiles longer than 10 mm were exposed to a pulse of LF-R, FR, or VLF-R light and were kept in the dark. Their coleoptile lengths were measured 2 days after the irradiation. Exposure to a pulse of LF-R light (∼1 mmol m−2) completely inhibited the growth of coleoptiles in both the wild type and osphyA-1 (Figure 6, LF-R). Subsequent exposure to a pulse of FR light (∼20 mmol m−2) partly reversed the effect of LF-R light exposure in the wild type (Figure 6, LF-R/FR). This LF-R/FR reversible response was observed much more clearly in osphyA-1 (Figure 6, LF-R, LF-R/FR, and LF-R/FR/LF-R). These results indicate that phyA is not involved in this LF-R/FR reversible control of growth inhibition in the rice coleoptile.

Figure 6.

Effects of a Pulse of Light Irradiation on Coleoptile Growth in Young Seedlings of Rice phyA Mutants.

The wild type (Akitakomachi; open bars) and the osphyA-1 mutants (hatched bars) were germinated and grown in the dark for 4 days (d) as described in Methods and then exposed to the following light regimens: Dark, kept in the dark; LF-R, a pulse of LF-R; LF-R/FR, a pulse of LF-R followed by a FR pulse; LF-R/FR/LF-R, a pulse of LF-R followed by FR and then LF-R pulses; VLF-R, a pulse of VLF-R light; FR, a pulse of FR. After the light irradiation, seedlings were kept in the dark for 48 hr, and coleoptile lengths were measured from 30 seedlings. Error bars represent se.

Next, we examined the effect of VLF-R and FR light and found that a pulse of either FR light (20 mmol m−2) or VLF-R light (∼1 μmol m−2) was able to inhibit growth of the coleoptile in the wild type but not in osphyA-1 (Figure 6, VLF-R and FR). These results indicate that the inhibition of coleoptile elongation by a pulse irradiation of VLF-R or FR light in etiolated rice seedlings is mediated primarily by phyA.

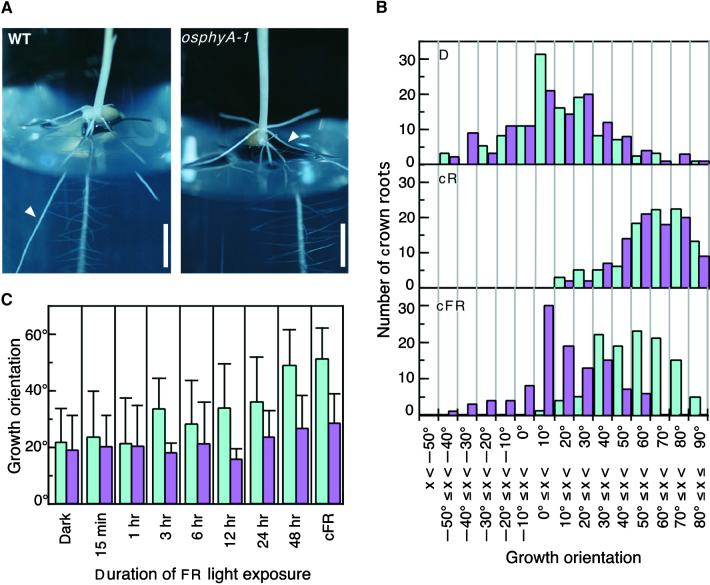

Root Gravitropic Response

We found another phenotypic difference in the root growth between wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings. Growth orientations of crown roots under different light conditions are presented in Figure 7. In the dark, the crown roots of both wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings grew mostly horizontally (Figures 7B and 7D). In other words, the crown roots of dark-grown rice seedlings are plagiotropic (growing parallel or nearly parallel to the surface). Under continuous R light, the gravitropic response of crown roots was induced and the roots grew with a peak frequency distribution at +50 to +80° in both wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings (Figure 7B, cR). Wild-type seedlings grown in continuous FR light showed a similar geotropic response as seedlings grown in continuous R light, although the peak of the distribution in continuous FR light shifted slightly toward horizontal (Figure 7B, cFR). Crown roots of osphyA-1 were insensitive to continuous FR light, because their orientation was similar to that observed in the dark-grown seedlings (Figure 7B, cFR). These results indicate that the gravitropic response of rice crown roots is modulated by continuous irradiation with both R and FR light and that the phyA mutation caused the loss of response to continuous FR light.

Figure 7.

Effect of Light on the Growth Orientation of Crown Roots of Wild Type (WT) and phyA Mutants.

(A) Representative photographs of crown roots of wild-type (Akitakomachi) and osphyA-1 seedlings grown under continuous FR light for 11 days. White arrowheads indicate first growing crown roots.  .

.

(B) Histograms of growth angles of crown roots. Wild-type (Akitakomachi) and osphyA-1 seedlings were maintained in complete darkness (D) or were grown under continuous R light (cR) or continuous FR light (cFR) for 11 days. Angles of crown roots were measured from the horizontal axis and divided into 10° intervals. The numbers of crown roots of wild-type and osphyA-1 seedlings are indicated by light blue and magenta bars, respectively.

(C) Effects of continuous FR light on the gravitropic growth orientation of the first growing crown roots (indicated by white arrowheads in [A]). Four-day-old etiolated seedlings of wild type (Akitakomachi; light blue bars) and osphyA-1 mutants (magenta bars) were irradiated with continuous FR light for intervals ranging from 15 min to 48 hr and kept in darkness until the 7th day. The growth angles of the first-grown-crown roots were measured. As controls, those of the seedlings grown in the dark or under the continuous FR light are shown. Error bars represent se; n  .

.

We examined crown roots to find the duration of prolonged irradiation with FR light needed for the induction of the gravitropic response. Five crown roots emerge sequentially from the nodal portion of the rice coleoptile (Hoshikawa, 1989). We examined only the first of these five to emerge (Figure 7A, white arrowheads). Four-day-old etiolated seedlings, when the length of the first crown roots was ∼9 ± 2 mm (most sensitive stage to FR light for detection of this response), were exposed to various durations of continuous FR light from 15 min to 48 hr. They were grown in the dark until growth measurement at the 7-day-old stage. The growth angles of the first crown roots were measured and compared with those of seedlings grown in the dark or continuous FR light as a control (Figure 7C). When the wild-type seedlings were exposed to continuous FR light for 1 hr or less, the growth orientation of the crown root was equivalent to that of seedlings grown in the dark (Figure 7C). In one ∼24-hr treatment, longer exposure times produced a larger growth angle in the first crown roots in wild-type seedlings (Figure 7C). The FR light irradiation for 48 hr caused the equivalent effect on this response obtained by continuous FR light irradiation (Figure 7C). In contrast, osphyA-1 mutants treated with various durations of continuous FR light showed growth orientation angles as large as those of seedlings grown in the dark (Figure 7C). Irradiation with VLF-R light (∼1 μmol m−2) did not induce the gravitropic response of the first growing crown root in wild-type seedlings (data not shown). Essentially, similar effects of continuous FR light and VLF-R light on the second growing crown roots were observed (data not shown). These results indicate that gravitropic growth orientation was induced only when the wild-type seedlings were exposed to a prolonged FR light irradiation (more than 3 hr).

The seminal roots, in contrast to crown roots, grew at an angle between +70 and +90° below horizontal, irrespective of the presence or absence of light in both wild-type and phyA mutant seedlings. Thus, gravitropic growth orientation in rice seminal roots is light independent.

Phenotypes of Mature Plants of Rice phyA Mutants

To compare the phenotypic peculiarities exhibited by the mature plants, both wild-type and phyA mutant plants were raised in the paddy field, and plant shape, plant height, and heading day were observed. However, we could not detect any significant differences for the measured phenotypic traits. Because the variety Nipponbare is strongly photoperiod sensitive, we carefully measured the heading date of osphyA-2 mutant lines. But no significant difference was observed between wild-type and osphyA-2 mutant plants. The mean days-to-heading value for wild-type plants (n = 21) was 112.7 ± 1.2 days and that for osphyA-2-10 plants (n = 70) was 112.5 ± 2.5 days. We also raised the wild-type and mutant plants under short day (10.5 hr of light/13.5 hr of dark) conditions, but still no significant difference was observed for days to heading in either genotype (wild-type, 50.0 ± 1.5 days [n = 32]; osphyA-2-9 with wild-type allele, 51.7 ± 1.4 days [n = 13]; osphyA-2-10 with mutant allele, 51.6 ± 1.7 days [n = 14]). Therefore, rice phyA mutants were morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type plants when grown under natural light conditions.

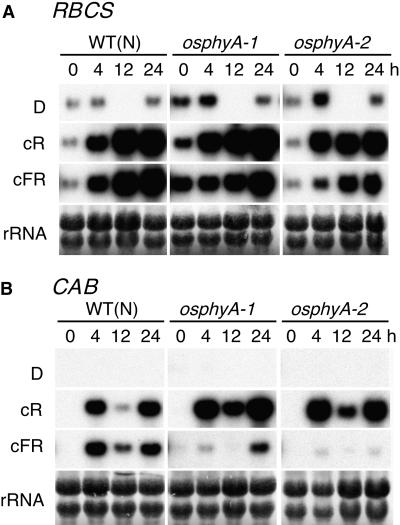

Expression Patterns of Light-Regulated Genes

We determined the effect of R and FR irradiation on the abundance of transcripts for CAB and RBCS genes in the wild type and phyA mutants. Mutant and wild-type plants were grown in complete darkness for 7 days and exposed to continuous R or FR light. Control seedlings were kept in constant darkness during the experiment. The seedlings were harvested 0, 4, 12, and 24 hr after the irradiation and the accumulation of CAB and RBCS transcripts was investigated by RNA gel blot analysis. As shown in Figure 8A, RBCS transcripts were present at a low level even in the dark, and the amount of these transcripts was increased equally by both R and FR light in wild-type plants. In phyA mutant plants, R light exerted the same effect as in wild-type plants, as expected. Unexpectedly, however, RBCS gene expression was induced in phyA mutants by continuous FR light to almost the same level as in wild-type plants. In the case of CAB gene expression (Figure 8B), we were not able to detect any signal in the dark (column D or row 0 hr) samples. Both R and FR light induced an accumulation of CAB transcripts in wild-type plants, which showed a fluctuation due to circadian rhythms. In phyA mutant plants, R light induced the same CAB gene expression pattern as in wild-type plants. FR light treatment also resulted in a similar fluctuation of CAB gene expression, although this expression level was much lower than that of wild-type plants. These results show that phyA seems to play a minor role in the induction of RBCS gene expression by FR light, whereas for the induction of CAB gene expression by FR light, phyA clearly play a more prominent role, although other photoreceptor(s) must also be involved.

Figure 8.

Induction of CAB and RBCS Genes by R and FR Light in Wild-Type (WT) and phyA Mutant Seedlings.

Seven-day-old etiolated seedlings of wild type (Nipponbare [N]) and two independent phyA mutants (osphyA-1and osphyA-2) were exposed to continuous R light (cR) or continuous FR light (cFR) for 0, 4, 12, and 24 hr (h) and harvested for RNA isolation. Control seedlings were kept continuously in the dark (D) and harvested at the same time point as cR- or cFR-treated seedlings. Samplings at the time point of 12 hr were skipped. Five micrograms of total RNA was blotted and hybridized with rice CAB and RBCS probes. rRNA was stained with methylene blue.

DISCUSSION

Isolation of Rice phyA Mutants from Mutant Panels

In this article, we report the isolation and characterization of phyA mutants in a monocot (rice) plant. Identification and characterization of mutants in living organisms is indispensable to efforts to understand and elucidate the function of particular genes. Mutants for phytochrome genes have been isolated in Arabidopsis and several other dicot species (Koornneef and Kendrick, 1994; Fankhauser and Chory, 1997). We used the gene knockout system (Hirochika, 1997, 1999) to isolate the rice phyA mutants, because isolation of mutants in rice by phenotypic selection was not as easy as in Arabidopsis.

Site-directed manipulation of chromosomal genes is a powerful tool with which to investigate the in situ function of isolated genes. A gene knockout system has been established in mice to produce phenotypes resulting from the elimination of functional genes or the loss of gene function. However, in plants, gene targeting has not become widely used because of the low frequency of homologous recombination (Thykjaer et al., 1997; Gallego et al., 1999; Jelesko et al., 1999). The transposon-tagging system provides an alternative method in plants to knock out specific genes. In this system, instead of targeting a specific gene, large populations of mutants (mutant panels) are generated by random insertion of retrotransposons and the mutants for a gene of interest are isolated by PCR-based screening of mutant panels. We used this system to isolate several independent lines in which the PHYA gene was knocked out.

In each of the phyA mutant lines, an exon of the PHYA gene was interrupted by the insertion of Tos17 sequence (Figure 1) and an in-frame stop codon was produced just downstream of the insertion site. These sequences have the potential to produce truncated PHYA molecules. However, the aberrant transcripts corresponding to the truncated PHYA molecules seem not to be translated, because immunodetectable bands were absent from two mutant lines (osphyA-1-2 and osphyA-2-10; Figure 3). The transcript level of the PHYA gene also was determined in the etiolated seedlings by RNA gel blot analysis. An expected, the transcript length of PHYA (4 kb) was not detected in either osphyA-1-2 or osphyA-2-10. Therefore, we categorized these mutant lines as null mutants for the phyA function.

Each mutant line in the mutant panels that we used has 5 to 10 copies of transposed Tos17. Thus, it is important to eliminate the possible effects of the insertion of Tos17s into genes other than PHYA. Fortunately, we were able to isolate three independent mutant lines (osphyA-1, osphyA-2, and osphyA-3) and found the same phenotypes from the two mutant lines we checked (osphyA-1 and osphyA-2), which proved that the phenotypes observed in the present study were caused by the loss of function of PHYA.

Role of phyA in the Photomorphogenesis of Rice Seedlings

Screening of the mutant panels resulted in the isolation of three allelic phyA mutants that show a dramatically reduced morphological response to continuous FR light, including inhibition of coleoptile and mesocotyl elongation and of the gravitropic response of crown roots (Figures 4, 5, and 7). Together with the sequence analysis (Figure 1) and immunochemical data (Figure 2), these results indicate that the altered photomorphogenesis in the phyA mutants results from a deficiency in functional phyA and that phyA is the predominant phytochrome in the dark-grown seedlings that mediates deetiolation responses induced by continuous FR light in rice. On the other hand, when grown under continuous R light (Figures 4, 5, and 7) or white light (data not shown), the phenotypic properties of phyA seedlings were essentially the same as those of the wild type, suggesting that phyA is mostly dispensable for the photomorphogenesis of rice seedlings under these conditions.

A pulse irradiation of LF-R light is known to inhibit the elongation of coleoptiles of rice seedlings when the coleoptile is longer than 10 mm (Pjon and Furuya, 1967). This response was partially reversed by subsequent irradiation with a pulse of FR light, indicating that it was the R/FR reversible response (Pjon and Furuya, 1967). In the present study, we repeated the same experiment for the phyA mutants and found that they showed significantly clearer reversibility of R/FR response compared with the wild type (Figure 6, LF-R, LF-R/FR, and LF-R/FR/LFR). We think that in the wild type, the FR pulse–induced reverse response mediated mainly by phyB was almost canceled by phyA-mediated growth inhibition induced by the FR pulse. The results presented here clearly show that the coleoptile elongation in wild-type plants is inhibited by a FR light pulse and are consistent with the results using a single short exposure (Pjon and Furuya, 1967) or hourly pulses of FR light exposure (Casal et al., 1996). In addition, we have demonstrated that a pulse of VLF-R or FR light that inhibited the coleoptile elongation in wild-type seedlings was not effective for the inhibition of coleoptile elongation in phyA mutants (Figure 6, VLF-R and FR). These results indicate that the growth inhibition of coleoptiles in rice seedlings is mediated by phyA in VLFR mode as well as by other phytochromes (probably phyB) in LFR mode of photoperception. It is interesting to note that the light-induced inhibition of the coleoptile and mesocotyl elongation is mediated by the different light perception modes. A pulse of VLF-R or FR light was able to induce the inhibition of the coleoptile elongation, whereas a prolonged FR light irradiation was required to inhibit the mesocotyl elongation and VLF-R light was not effective for the inhibition. Therefore, as far as phyA is concerned, the light-induced inhibition of the coleoptile is mediated by VLFR mode and that of the mesocotyl by HIR mode. Moreover, we used the phyA mutants to present direct evidence that phyA mediates FR light–induced gravitropic growth in the crown roots of rice (Figure 7). The effects of light on gravitropic responses have been reported in many organs of various plant species, including coleoptiles of oat (Blaauw, 1961) and maize (Wilkins and Goldsmith, 1964) and roots of maize (Mandoli et al., 1984; Feldman and Briggs, 1987). However, the reported effects varied greatly depending on the plant species and the organs, and the variation could be attributed in large part to the existence and involvement of multiple photoreceptors. Arabidopsis was the only plant species in which an assignment of phytochrome molecular species involved in the gravitropic responses was determined using phytochrome-deficient mutants (Robson et al., 1996). According to that report, hypocotyls of Arabidopsis exhibit negative gravitropism (growing against the gravity vector) in the dark, and either phyA or phyB is capable of inducing randomization of the direction of hypocotyl growth in R light.

In terms of root gravitropism, it has been suggested that roots of many plant species grow in diagravitropic orientation in the dark and that light induces their gravitropic growth (Feldman, 1984). For example, in maize (var Merit), light-induced gravitropic response in etiolated primary roots is mediated by both LFR, showing R/FR reversibility (Mandoli et al., 1984), and VLFR, showing that FR light could not reverse the R light induction (Feldman and Briggs, 1987). These observations suggested the involvement of multiple phytochromes in the induction of gravitropic responses. However, we have presented here conclusive evidence that phyA induces gravitropic growth in the crown roots of rice through continuous FR light, and photoreceptor(s) other than phyA seem to induce the same response in LF-R light (Figure 7).

It is interesting to note that in rice, such light-induced gravitropic bending was observed only in the crown roots and not in the seminal (primary) roots, which grow straight down irrespective of the light treatment (Figure 7A). In maize, the primary roots show the light-induced gravitropism (Feldman and Briggs, 1987). Therefore, there seem to be variations among plant species in the light-induced gravitropic response. In rice, crown roots emerge from nodal portions and tend to develop horizontally. Because the crown roots, which come out from higher nodes, start developing horizontally into air or water, they need to bend downward to reach the soil. Therefore, light-induced changes in root gravitropism could be an adaptive mechanism, and immunochemically detectable PHYA that is highly accumulated in the root cap (Hisada et al., 2000) may play some role in light-induced gravitropism.

Phenotypes of Mature phyA Mutants of Rice

Only a limited number of phyA mutants have been reported to date, including the loss-of-phyA-function mutants of Arabidopsis (Nagatani et al., 1993; Parks and Quail, 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993), tomato (van Tuinen et al., 1995), and pea (Weller et al., 1997). In Arabidopsis and tomato, phyA deficiency was reported to have little effect on the morphological appearance of mature plants grown under white light. In contrast, phyA-deficient pea mutants (fun1-1) showed a highly pleiotropic phenotype when they were grown to maturity under long day conditions (Weller et al., 1997), indicating that phyA is involved in the detection of daylength in pea.

In rice, we did not detect a significant difference between mutant and wild-type plants grown under natural light conditions for any of the measured phenotypic traits. Clough et al. (1995) overexpressed the oat PHYA gene in rice, but the transgenic rice plants were not phenotypically different from wild-type plants when grown under high fluence white light. These observations indicate that phyA has little effect in mature rice plants grown under natural light conditions.

Rice cv Nipponbare is strongly photoperiod sensitive, and a delay in flowering is noted under long-day conditions. In short-day conditions (10.5 hr of light/13.5 hr of dark), both wild-type and osphyA-2 plants started heading ∼50 days after sowing, whereas in natural light conditions (long-day conditions), the days to heading was prolonged to ∼113 days in both osphyA-2 and the wild type. These observations suggest that phyA does not play an important role in photoperiod sensing for flowering in rice. Recently, Izawa et al. (2000) showed that the photoperiodic sensitivity 5 (se5) mutant, which is completely deficient in photoperiodic response (Yokoo and Okuno, 1993), lacks the phytochrome chromophore and therefore has no functional phytochromes. In their work, se5 flowered very early even under long-day conditions (14 hr of light/10 hr of dark), which indicates that some phytochrome species detect the long-day photoperiod and mediate the delay in flowering. Because our phyA mutants responded to the long-day photoperiod, we can say that the delay in flowering observed by Izawa et al. (2000) was due to some phytochrome species other than phyA.

Expression of CAB and RBCS Genes in phyA Mutants

Phytochromes are known to mediate the induction of expression for genes involved in photosynthesis (Kuno et al., 2000). In particular, CAB and RBCS genes are well-characterized nuclear genes whose expression is regulated by phytochromes at the transcriptional level. The loss of phyA function in the phyA mutants should alter the expression pattern of CAB and RBCS genes. In Arabidopsis, it was reported that irradiation with both VLF-R and FR light could induce the expression of the CAB gene in phyB mutants, whereas in the phyA mutants, CAB gene expression could be induced by LF-R light but not by FR light (Hamazato et al., 1997). These results suggest that phyA is the sole photoreceptor in Arabidopsis that can induce CAB gene expression upon irradiation with FR light in dark-grown seedlings.

In rice phyA mutants, however, FR light induced RBCS and CAB gene expression in dark-grown seedlings at different levels. The induction of RBCS gene expression was almost to the same level as in wild-type plants (Figure 8A), whereas the induction level of CAB gene expression was much less in phyA mutants than in wild-type plants (Figure 8B). These results show that phyA contributes to the accumulation of RBCS and CAB transcripts differently under FR light and also suggest that photoreceptor(s) other than phyA can mediate the expression of these genes in response to irradiation with FR light in etiolated rice seedlings. Only three phytochrome genes (PHYA, PHYB, and PHYC) have been reported to date in rice (Tahir et al., 1998), and phyB is assumed to be a sensor for classic R/FR photoreversible responses (Shinomura et al., 1996). Therefore, phyC could be a candidate photoreceptor for such photoresponse. In Arabidopsis, phyC is thought to be a type II phytochrome based on its photostable nature and its small amount in both etiolated and green plants, but its photoregulatory roles have not been fully elucidated because monogenic mutants of phyC have yet to be isolated (Quail, 1998). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that phyC mediates the CAB gene expression induced by FR light. Regardless of the facts to be established in the future, the present study demonstrates that a photoreceptor(s) other than phyA perceives FR light for the induction of CAB gene in the etiolated seedlings.

Modes of phyA Action in Rice

The present study has demonstrated that the photoinhibition of coleoptile elongation in rice induced by a pulse of light irradiation is mediated by both phyA in VLFR mode and probably phyB in LFR mode. In contrast, the photoinhibition of mesocotyl elongation and the light-dependent gravitropic response of crown roots are HIRs and are mediated by phyA under continuous FR light and by some other phytochrome(s) under continuous R light.

The results presented here clearly show that rice phyA controls photomorphogenesis in two distinct modes of photoperception—VLFR and HIR—and are consistent with the results obtained for phyA mutants in Arabidopsis and tomato (Nagatani et al., 1993; Parks and Quail, 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993; Reed et al., 1994; van Tuinen et al., 1995). In Arabidopsis, phyA is known to control development and growth (Chory et al., 1996) in several different modes of action, including seed germination in VLFR mode (Shinomura et al., 1996) and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in FR light–induced HIR mode (Nagatani et al., 1993; Parks and Quail, 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993). Therefore, phyA seems to play a similar role in the deetiolation of monocot and dicot plants, in spite of the fact that FR light induces the inhibition of coleoptile elongation in monocots (i.e., rice) and hypocotyl elongation in dicots (i.e., Arabidopsis). Although elongation inhibition of both coleoptiles and hypocotyls seems to result from the inhibition of cell elongation, the modes of photoperception by phyA in those responses are quite different, the former being via VLFR and the latter being via HIR (Shinomura et al., 2000).

This difference raises the question of whether the two modes of responses via phyA—VLFR and HIR—are completely different or share some overlapping pathways. Recent findings in phytochrome biochemistry, including nuclear localization and kinase activity, might lead us to a plausible explanation for these physiological responses (Reed, 1999; Neff et al., 2000). Important work in this regard includes the following: (1) intracellular localization studies of phyA (Kircher et al., 1999; Hisada et al., 2000); (2) the demonstration of light-dependent kinase activity of oat phyAs (Wong et al., 1989; Biermann et al., 1994; Yeh and Lagarias, 1998); and (3) the identification of a protein that can be phosphorylated by oat phyA in a light-regulated manner (Fankhauser et al., 1999). On the basis of such information, it can be hypothesized that phyA signaling for photomorphogenesis responses may depend on combinations of the variables, including nuclear versus cytoplasmic location, phosphorylated versus unphosphorylated, and dark-synthesized Pr, photoconverted Pfr, and photocycled Pr. It remains to be determined in the near future which proteins interact with each species of phyA described above and how these various control mechanisms interact with each other.

Perspective

In rice, a minimum of three phytochrome genes (PHYA, PHYB, and PHYC) are expressed (Tahir et al., 1998). Recent evidence in Arabidopsis indicates that individual members of the phytochrome family show different manners of photoperception (Shinomura et al., 1996) and have specialized functions (Reed et al., 1994; Quail, 1998; Whitelam et al., 1998). To characterize the functions of all known phytochromes in rice, we have also been attempting to isolate phyB and phyC mutants from the mutant panels of rice, but no candidates have been obtained to date. On the other hand, we recently identified three additional mutant alleles of the PHYA gene from the mutant panels. Previously, Hirochika et al. (1996) analyzed the border sequences of eight random Tos17 insertion sites and found one of them to be a PHYA gene. Therefore, the chromosomal region where PHYA resides appears to be a focus for the transposition of Tos17. In fact, the findings of Hirochika's group inspired us to attempt the isolation of Tos17 insertional mutants of phytochrome genes in rice. We have screened 11,600 mutant lines so far, but our failure to obtain the phyB and phyC mutants indicates that Tos17-induced mutations must be saturated to make this system applicable to any gene of interest. We would need to produce a large number of mutagenized lines to achieve this saturation level, and further screening of the upcoming panels is expected to reveal the phyB and phyC mutants.

METHODS

Isolation of phyA Mutants from Mutant Panels

Large populations of rice (Oryza sativa) mutants generated by means of Tos17-mediated mutagenesis were made available by the Laboratory of Gene Function at the National Institute of Agrobiological Resources (Tsukuba, Japan). Details of mutagenesis with Tos17 have been described (Hirochika, 1999). To identify phyA mutants from a large mutant population, the mutant lines were divided into several groups, and within each group the lines were aligned as two- or three-dimensional matrices. A particular group of mutant lines was termed a “mutant panel.” For example, a mutant panel of 625 lines consisted of a matrix in which all of the mutant lines were aligned in 25 rows and 25 columns. Plant samples were collected and mixed to make a pool for DNA extraction from all of the individual mutants in a particular row or column. The pooled DNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis so that a maximum of 50 (25 + 25) PCR reactions were enough to survey 625 mutant lines. A mutant line with the insertion of Tos17 in a specific gene could be identified by using primers specific to the gene of interest and Tos17. If a desired mutant exists in the panel, DNA pools from one row and one column must give amplified DNA fragments of the same size, and the mutant line can be addressed on the matrix by the row/column number.

Screening for the phyA Mutant by PCR Amplification

We screened three mutant panels (NA0, NB0, and NC0) for the isolation of phyA mutants. NA0 was a two-dimensional (23 × 24) mutant panel, whereas NB0 and NC0 were three-dimensional (8 × 10 × 12) panels. Table 1 lists the details of two Tos17-specific primers (LTR1 and LTR4) and four PHYA-specific primers (AF, BF, CF, and ER) that were used in all possible combinations for PCR amplification of 300 ng of genomic DNA from each pooled DNA sample. To eliminate nonspecific amplifications, we designed additional PHYA-specific (AF1, BF1, CF1, and ER1) and Tos17-specific (LTR2 and LTR5) primers just upstream of each primer for nested PCR (Table 1). The amplified DNA fragments were cloned and sequenced to confirm the insertion of Tos17.

Table 1.

Nucleotide Sequences of PHYA- and Tos17-Specific Primers

|

PHYA-Specific Primer Namea |

PHYA-Specific Primer Sequence | Primer Positionb |

Tos17-Specific Primer Namec |

Tos17-Specific Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF | GAAGCATGGAGGTGCTATGC | 5278–5297 | LTR1 | TTGGATCTTGTATCTTGTATATAC |

| AF1 | TATGCAATACGGTGGTCAAGG | 5293–5313 | LTR2 | GCTAATACTATTGTTAGGTTGCAA |

| BF | CCAACATCATGGACCTTGTG | 5944–5963 | LTR4 | CTGGACATGGGCCAACTATACAGT |

| BF1 | ACGTGATATTGCCTTCTGGC | 6038–6057 | LTR5 | CCAATGGACTGGACATCCGATGGG |

| CF | CCTCATCCATCGAGTTCTAGC | 4327–4347 | ||

| CF1 | ATCTTGTTCAGCAGGAGTGG | 4558–4577 | ||

| ER | AGGATGAAGGTTGACATGCC | 8583–8564 | ||

| ER1 | GACATCGCCATTCATGAGC | 8545–8527 |

AF1, BF1, CF1, and ER1 are the nested PCR primers of AF, BF, CF, and ER, respectively.

Position of the first and last nucleotides in phy18 (PHYA) sequence (GenBank accession number X14172).

LTR2 and LTR5 are the nested PCR primers of LTR1 and LTR4, respectively.

Genomic DNA Isolation and DNA Gel Blot Hybridization

Genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves using the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide method (Murray and Thompson, 1980). The genotype analysis was performed using 2 μg of genomic DNA digested with PstI, fractionated on an 0.8% agarose gel, and transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). A full-length clone of PHYA cDNA was random labeled and used as a probe for the genotype analysis.

Immunochemical Analysis

Crude protein extracts were prepared from 7-day-old etiolated seedlings of wild type and phyA mutants for the immunochemical detection of PHYA. Approximately 0.5 g of seedlings was homogenized in the presence of 1 mL of phytochrome extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The supernatant was recovered after centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 min twice, and 0.66 volume of saturated ammonium sulfate was added. The resultant precipitate was dissolved in 100 μL of phytochrome extraction buffer, and the protein concentration was determined. Fifty micrograms of each protein extract was separated by SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide gel) and electroblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. The monoclonal antibody used in this study was the anti-rye PHYA antibody (mAR07) from the monoclonal antibody stock at the Hitachi Advanced Research Laboratory (Hatoyama, Japan). Immunochemical detection was performed using an immunoblot kit (alkaline phosphatase system; Bio-Rad).

Plant-Growth Measurement and Light Treatment

For measurements of coleoptile and mesocotyl length, dehusked rice seed were surface sterilized and placed on 0.6% agar in glass tubes. The glass tubes were kept in a light-tight box at 4°C for 3 days. Seed were placed on the agar so that embryos had an upward orientation. The seed in the glass tubes were transferred subsequently to 25°C in the dark for 24 hr before the light treatment. In the experiment with continuous light irradiation, seedlings were exposed to continuous red (R) light (photon fluence of 50 μmol m−2 sec−1) or continuous far-red (FR) light (photon fluence of 90 μmol m−2 sec−1) for 11 days. For the experiments with different intervals of continuous FR light treatments on mesocotyl growth, 2-day-old etiolated seedlings were irradiated with continuous FR light for intervals ranging from1 hr to 5 days and kept in darkness until the measurement on the 7th day. For irradiation with pulses of light, 4-day-old etiolated seedlings with coleoptile lengths of 13.2 ± 1.5 mm in the wild type and 10.9 ± 1.4 mm in osphyA-1 were exposed to a pulse of R light (17.8 μmol m−2 sec−1 for 56 sec for low fluence R [LF-R], 142 nmol m−2 sec−1 for 7 sec for very low fluence [VLF-R]) and/or FR light (28.4 μmol m−2 sec−1 for 703 sec) and then kept in the dark for 2 days until the measurement. The lengths of coleoptiles and mesocotyls were measured using a digimatic caliper (CD-15C; Mitsutoyo, Tokyo, Japan). The R and FR light were obtained using broad-band filters according to Shinomura et al. (1994). For measurement of the growth orientation of crown roots and seminal roots, seedlings were grown in the dark or under continuous R or FR light for 7 days. The orientation of root growth was measured using a protractor as the angle between the horizontal plane (0°) and the orientation of the proximal 10-mm part of crown roots of 10 to 30 mm in length (or of the seminal root of 20 to 80 mm in length). Orthogravitropic orientation was measured as a positive angle. All experiments were conducted three times with 30 to 50 plants per data point. To examine the effect of different intervals of continuous FR light treatments on gravitropic growth orientation of the first growing crown roots, 4-day-old etiolated seedlings were irradiated with continuous FR light for intervals ranging from 15 min to 48 hr and kept in darkness until the measurement on the 7th day.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Seed of Nipponbare and the mutant line osphyA-2-10 were sown on April 21, 1999, and seedlings were transplanted on May 26 in an irrigated rice field. Plants were grown under natural daylength conditions, and the heading date was monitored for the appearance of the first panicle. Nipponbare and mutant lines osphyA-2-10 and osphyA-2-9 also were grown in a growth chamber in short-day conditions (28°C; light cycle, 10.5 hr of light/13.5 hr of dark).

RNA Isolation

For RNA isolation, dehusked and sterilized seed were sown on 0.8% agar and kept at 4°C for 1 day. The rice seedlings were grown at 28°C for 7 days in complete darkness and then transferred to continuous R light (2.0 μmol m−2 sec−1) or FR light (29 μmol m−2 sec−1). The seedlings were harvested at 4 time points (0, 4, 12, and 24 hr) after the irradiation. Light sources were white fluorescent tubes filtered through two layers of R film (red No. 22; Tokyo Butai Shomei, Tokyo, Japan) for R light and special FR fluorescent tubes (FL20S.FR-74; Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) filtered through red and blue film (red No. 22 and blue No. 72; Tokyo Butai Shomei) for FR light. The seedlings to be used as controls were kept in the dark. Total RNA for the light-induced gene expression experiments was isolated from leaf parts of seedlings with the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Hanzawa for providing monoclonal antibody, W. Kurihara for immunochemical analysis, K. Ikeda for physiological experiments, and Prof. T. Yokota for discussion and support. We are grateful to Drs. M. Tahir, J.M. Reed, and C. Scutt for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank K. Yagi and Y. Iguchi for their technical assistance. This work was partly supported by grants from the Program for the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences, Japan, to M.T., H.H., and M.F. and from the Hitachi Advanced Research Laboratory (Grant B2023) to M.F.

References

- Biermann, B.J., Pao, L.I., and Feldman, L.J. (1994). Pr-specific phytochrome phosphorylation in vitro by a protein kinase present in anti-phytochrome maize immunoprecipitates. Plant Physiol. 105, 243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw, O.H. (1961). The influence of blue, red and far-red light on geotropism and growth of the Avena seedling. Acta Bot. Neerl. 10, 397–450. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, W.R., and Huala, E. (1999). Blue-light photoreceptors in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 33–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, W.R., Mandoli, D.F., Shinkle, J.R., Kaufman, L.S., Watson, J.C., and Thompson, W.F. (1984). Phytochrome regulation of plant development at the whole plant, physiological, and molecular levels. In Sensory Perception and Transduction in Aneural Organisms, G. Colombetti, F. Lenci, and P.-S. Song, eds (New York: Plenum Press), pp. 265–280.

- Casal, J.J., Clough, R.C., and Vierstra, R.D. (1996). High-irradience response induced by far-red light in grass seedlings of the wild type or overexpressing phytochrome A. Planta 200, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, K.L., Miller, F.R., Pratt, M.M.C., Pratt, L.H., Morgan, P.W., and Mullet, J.E. (1997). The sorghum photoperiod sensitivity gene, Ma3, encodes a phytochrome B. Plant Physiol. 113, 611–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory, J., Chatterjee, M., Cook, R.K., Elich, T., Fankhauser, C., Li, J., Nagpal, P., Neff, M., Pepper, A., Poole, D., Reed, J., and Vitart, V. (1996). From seed germination to flowering, light controls plant development via the pigment phytochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 12066–12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, A.H., and Quail, P.H. (1989). Structure and expression of a maize phytochrome-encoding gene. Gene 85, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack, T., Mathews, S., and Sharrock, R.A. (1994). The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: The sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 413–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, R.C., Casal, J.J., Jordan, E.T., Christou, P., and Vierstra, R.D. (1995). Expression of functional oat phytochrome A in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol. 109, 1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehesh, K., Tepperman, J., Christensen, A.H., and Quail, P.H. (1991). phyB is evolutionarily conserved and constitutively ex-pressed in rice seedling shoots. Mol. Gen. Genet. 225, 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (1997). Light control of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., Yeh, K.C., Lagarias, J.C., Zhang, H., Elich, T.D., and Chory, J. (1999). PKS1, a substrate phosphorylated by phytochrome that modulates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 1539–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, L.J. (1984). Regulation of root development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 35, 223–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, L.J., and Briggs, W.R. (1987). Light-regulated gravitropism in seedling roots of maize. Plant Physiol. 83, 241–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya, M. (1993). Phytochromes: Their molecular species, gene families, and functions. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 617–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, M.E., Sirand-Pugnet, P., and White, C.I. (1999). Positive-negative selection and T-DNA stability in Arabidopsis transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 39, 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazato, F., Shinomura, T., Hanzawa, H., Chory, J., and Furuya, M. (1997). Fluence and wavelength requirements for Arabidopsis CAB gene induction by different phytochromes. Plant Physiol. 115, 1533–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, H.P., Barker, R.F., Idler, K.B., Lissemore, J.L., and Quail, P.H. (1985). Analysis of cloned cDNA and genomic sequences for phytochrome: Complete amino acid sequences for two gene products expressed in etiolated Avena. Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 8543–8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika, H. (1997). Retrotransposons of rice: Their regulation and use for genome analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika, H. (1999). Retrotransposons of rice as a tool for forward and reverse genetics. In Molecular Biology of Rice, K. Shimamoto, ed (Tokyo: Springer-Verlag), pp. 43–58.

- Hirochika, H., Sugimoto, K., Otsuki, Y., Tsugawa, H., and Kanda, M. (1996). Retrotransposons of rice involved in mutations induced by tissue culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 7783–7788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisada, A., Hanzawa, H., Weller, J.L., Nagatani, A., Reid, J.B., and Furuya, M. (2000). Light-induced nuclear translocation of endogenous pea phytochrome A visualized by immunocytochemical procedures. Plant Cell 12, 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshikawa, K. (1989). The Growing Rice Plant. (Tokyo: Nobunkyo).

- Izawa, T., Oikawa, T., Tokutomi, S., Okuno, K., and Shimamoto, K. (2000). Phytochromes confer the photoperiodic control of flowering in rice (a short day plant). Plant J. 22, 391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelesko, J.G., Harper, R., Furuya, M., and Gruissem, W. (1999). Rare germinal unequal crossing-over leading to recombinant gene formation and gene duplication in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10302–10307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S.A., Keith, B., Shinozaki, K., and Chua, N.H. (1989). The sequence of the rice phytochrome gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 2865–2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, S., Kozma-Bognar, L., Kim, L., Adam, E., Harter, K., Schafer, E., and Nagy, F. (1999). Light quality–dependent nuclear import of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A and B. Plant Cell 11, 1445–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef, M., and Kendrick, R.E. (1994). Photomorphogenic mutants of higher plants. In Photomorphogenesis in Plants, 2nd ed, R.E. Kendrick and G.M.H. Kronenberg, eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers), pp. 601–628.

- Kuno, N., Muramatsu, T., Hamazato, F., and Furuya, M. (2000). Identification by large-scale screening of phytochrome-regulated genes in etiolated seedlings of Arabidopsis using a fluorescent differential display technique. Plant Physiol. 122, 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandoli, D.F., Tepperman, J., Huala, E., and Briggs, W.R. (1984). Photobiology of diagravitropic Maize roots. Plant Physiol. 75, 359–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, H. (1962). Primary effects of light on growth. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 13, 465–488. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.G., and Thompson, W.F. (1980). Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 4321–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani, A., Reed, J.W., and Chory, J. (1993). Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 102, 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, M.M., Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (2000). Light: An indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 14, 257–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, B.M., and Quail, P.H. (1993). hy8, a new class of Arabidopsis long hypocotyl mutants deficient in functional phytochrome A. Plant Cell 5, 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pjon, C.-J., and Furuya, M. (1967). Phytochrome function in Oryza sativa L. I. Growth responses of etiolated coleoptiles to red, far-red and blue light. Plant Cell Physiol. 8, 709–718. [Google Scholar]

- Quail, P.H. (1998). The phytochrome family: Dissection of functional roles and signaling pathways among family members. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 353, 1399–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail, P.H., Boylan, M.T., Parks, B.M., Short, T.W., Xu, Y., and Wagner, D. (1995). Phytochromes: Photosensory perception and signal transduction. Science 268, 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.W. (1999). Phytochromes are Pr-ipatetic kinases. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.W., Nagatani, A., Elich, T.D., Fagan, M., and Chory, J. (1994). Phytochrome A and phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct functions in Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 104, 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson, P.R., McCormac, A.C., Irvine, A.S., and Smith, H. (1996). Genetic engineering of harvest index in tobacco through overexpression of a phytochrome gene. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 995–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock, R.A., and Quail, P.H. (1989). Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: Structure, evolution and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 3, 1745–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto, K. (1995). The molecular biology of rice. Science 270, 1772–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomura, T., Nagatani, A., Chory, J., and Furuya, M. (1994). The induction of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated principally by phytochrome B and secondarily by phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 104, 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomura, T., Nagatani, A., Hanzawa, H., Kubota, M., Watanabe, M., and Furuya, M. (1996). Action spectra for phytochrome A- and B-specific photoinduction of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8129–8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomura, T., Uchida, K., and Furuya, M. (2000). Elementary processes of photoperception by phytochrome A for high-irradiance response of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 122, 147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M., Kanegae, H., and Takano, M. (1998). Phytochrome C (PHYC) gene in rice: Isolation and characterization of a complete coding sequence. Plant Physiol. 118, 1535. [Google Scholar]

- Thykjaer, T., Finnemann, J., Schauser, L., Christensen, L., Poulsen, C., and Stougaard, J. (1997). Gene targeting approaches using positive-negative selection and large flanking regions. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tuinen, A., Kerckhoffs, L.H., Nagatani, A., Kendrick, R.E., and Koornneef, M. (1995). Far-red light-insensitive, phytochrome A–deficient mutants of tomato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246, 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller, J.L., Murfet, I.C., and Reid, J.B. (1997). Pea mutants with reduced sensitivity to far-red light define an important role for phytochrome A in day-length detection. Plant Physiol. 114, 1225–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam, G.C., Johnson, E., Peng, J., Carol, P., Anderson, M.L., Cowl, J.S., and Harberd, N.P. (1993). Phytochrome A null mutants of Arabidopsis display a wild-type phenotype in white light. Plant Cell 5, 757–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam, G.C., Patel, S., and Devlin, P.F. (1998). Phytochromes and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 353, 1445–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, M.B., and Goldsmith, M.H.M. (1964). The effect of red, far-red and blue light on the geotropic response of coleoptiles of Zea mays. J. Exp. Bot. 15, 600–615. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.-S., McMichael, R.J., and Lagarias, J. (1989). Properties of a polycation-stimulated protein kinase associated with purified Avena phytochrome. Plant Physiol. 91, 709–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K., and Sasaki, T. (1997). Large-scale EST sequencing in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, K.C., and Lagarias, J.C. (1998). Eukaryotic phytochromes: Light-regulated serine/threonine protein kinases with histidine kinase ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13976–13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoo, M., and Okuno, K. (1993). Genetic analysis of earliness mutations induced in the rice cultivar Norin 8. Jpn. J. Breed. 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar]