Abstract

For most ligand-dependent nuclear receptors, the status of endogenous ligand modulates the relative affinities for corepressor and coactivator complexes. It is less clear what parameters modulate the switch between corepressor and coactivator for the orphan receptors. Our previous work demonstrated that hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α1 (HNF4α1, NR2A1) interacts with the p160 coactivator GRIP1 and the cointegrators CBP and p300 in the absence of exogenously added ligand and that removal of the F domain enhances these interactions. Here, we utilized transient-transfection analysis to demonstrate repression of HNF4α1 activity by the corepressor silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (SMRT) in several cell lines and on several HNF4α-responsive promoter elements. Glutathione S-transferase pulldown assays confirmed a direct interaction between HNF4α1 and receptor interaction domain 2 of SMRT. Loss of the F domain resulted in marked reduction of the ability of SMRT to interact with HNF4α1 in vitro and repress HNF4α1 activity in vivo, although the isolated F domain itself failed to interact with SMRT. Surprisingly, loss of both the A/B and F domains restored full repression by SMRT, suggesting involvement of both domains in the SMRT interaction. Finally, we show that when coexpressed along with HNF4α1 and GRIP1, CBP, or p300, SMRT can titer out HNF4α1-mediated transactivation in a dose-dependent manner and that this competition derives from mutually exclusive binding. Collectively, these results suggest that HNF4α can functionally interact with both a coactivator and a corepressor without altering the status of any putative ligand and that the presence of the F domain may play a role in discriminating between the different coregulators.

Many key aspects of mammalian physiology, including growth, differentiation, and homeostasis, are governed by the actions of small, lipophilic compounds, including the steroid and thyroid hormones and vitamins A and D. These compounds function as ligands for many members of the nuclear receptor superfamily and modulate their transcriptional activities (for a review, see reference 69). Nuclear receptors, by definition, share a common modular architecture comprised of a highly conserved DNA binding domain (DBD) and a C-terminal ligand binding/transactivation domain (LBD), as well as more divergent N-terminal and central hinge domains (reviewed in references 42 and 53). Some receptors also possess a so-called F domain of variable length at the extreme C terminus. The various domains contain different motifs, such as activation functions (AFs), that are important in the regulation of many aspects of nuclear receptor function and, ultimately, in transcriptional activity. AF-2 (helix 12), located at the C terminus of the LBD, has been shown to play a critical role in ligand-induced activation of receptors, a role that derives from its ability to undergo ligand-dependent conformational changes necessary for recruitment of a class of accessory factors and protein complexes termed coactivators (reviewed in references 44 and 71). These complexes, by virtue of intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity (5, 49, 60) and/or via protein-protein interactions (12, 13, 61), have the net effect of relaxing and otherwise modifying chromatin structure such that formation of a stable preinitiation complex—a step considered rate limiting in transcriptional activation—can be achieved (reviewed in references 7, 14, 35, and 43).

Many ligand-dependent nuclear receptors also display transcriptional silencing properties, exerting receptor-mediated repression in the absence of an endogenous ligand (reviewed in references 1 and 63). This ability arises from a distinct conformation of the aporeceptor that promotes recruitment of corepressor polypeptides, designated SMRT (6) and N-CoR (24). These proteins, in turn, modulate the formation of a corepressor complex composed of proteins that possess histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity, an activity that ultimately promotes chromatin condensation and a transcriptionally nonpermissive state (20, 45; reviewed in references 4, 32, and 64). Thus, a strong correlation exists between ligand status and cofactor binding for these ligand-dependent receptors, the importance of which is underscored by the numerous pathologies associated with aberrant interaction with either a coactivator or a corepressor (22, 37, 52, 72).

The majority of the 160 known members of the nuclear receptor superfamily lack identified endogenous ligands and are therefore termed orphan receptors (58). The question therefore arises as to whether these orphan receptors can respond to coactivators and corepressors and to what extent such responses might resemble those observed for receptors whose transcriptional activities are known to depend on the presence or absence of a bona fide ligand.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α, NR2A1) is a highly conserved member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and an orphan receptor in that a functional, endogenous ligand has not been definitively identified. Nonetheless, HNF4α plays a critical role in the positive regulation of more than 60 target genes representing a broad range of physiological processes such as glucose, fatty acid, and cholesterol metabolism and blood coagulation in the liver, kidney, pancreas, and intestine. Aberrations in HNF4α activity, due to mutations in either the HNF4α gene itself or HNF4α-responsive elements in the promoters of target genes, give rise to several human diseases, such as hemophilia B Leyden and maturity-onset diabetes of the young 1 (MODY1). HNF4α also activates hepatitis B viral genes and plays a critical role in a transcriptional regulatory hierarchy in the liver. Deletion of the HNF4α-encoding gene from the mouse genome results in embryonic lethality characterized by arrested gastrulation, underscoring the importance of HNF4α in development (for a review, see reference 56).

We and others have traditionally considered the predominant isoforms of HNF4α, HNF4α1 and HNF4α2, to be constitutive activators due to the ability to activate transcription in the absence of an exogenously added ligand (55, 57), in the presence of serum stripped of lipophilic compounds (29), and in the absence of serum (F. M. Sladek, unpublished data). Additionally, HNF4α1 can stimulate transcription in vitro (19) and has exhibited activity in yeast cells (55). Along with others, we have shown that HNF4α1 and HNF4α2 can respond in vivo and in vitro to several coactivators, including GRIP1, SRC-1, and CBP/p300, in mammalian cells, as well as in yeast (39, 40, 55, 66, 73). We also showed that removal of the unusually large F domain of HNF4α1/2 greatly enhances the transcriptional response to coactivators. This response correlates with an increased ability to physically interact with GRIP1 in vitro, suggesting that the inhibitory function of the F domain at least partially derives from abrogation of optimal coactivator recruitment (55). However, we also noted that HNF4α1 does not activate transcription as robustly as most ligand-bound receptors (29) and that addition of sodium butyrate, which is known to inhibit histone deacetylase activity, greatly potentiated the transcriptional activity of HNF4α1 in transient-transfection assays (Sladek, unpublished data). We therefore sought to determine whether HNF4α1 might be able to interact with a corepressor and to ascertain the determinants that might modulate such an interaction.

Here, we show that the corepressor SMRT inhibits the ability of HNF4α1 to activate transcription in vivo and directly interacts with HNF4α1 in vitro. We also show that loss of the F domain diminishes this interaction both in vivo and in vitro, while removal of both the A/B and F domains restores the ability of HNF4α to optimally interact with SMRT. Finally, we demonstrate that transactivation by the coactivators GRIP1, CBP, and p300 can be competitively abolished, in a dose-dependent fashion, by cotransfected SMRT and that removal of the F domain greatly compromises this competition. Taken together, these results implicate the F domain as a key regulatory domain for HNF4α1 that helps discriminate between coactivators and corepressors. To our knowledge, this is the first report of modulation of recruitment of both a coactivator and a corepressor to a nuclear receptor by a non-ligand-dependent mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The expression vectors containing full-length rat HNF4α1 (pMT7.HNF4α1) (31); the HNF4α deletion constructs HNF4ΔAB (pMT7.HNF4.N45C455) (31), HNF4ΔF (pMT7.N1C374) (55), and HNF4ΔAB/ΔF (pMT7.N45C374) (31); full-length human retinoic acid (RA) receptor alpha (RARα) (pCMX.RARα) (65); full-length mouse RXRγ (pCMX.RXRγ) (41); full-length mouse CBP containing a C-terminal hemagglutinin tag (pRc/RSV.mCBP.HA.RK); full-length human p300 containing a C-terminal hemagglutinin tag (pCMV.HA.p300) (12); full-length mouse GRIP1 (pSG5.GRIP1) (10); and pSG5.SMRT containing the original 1,495 codons (6) have all been described previously. The GST.HNF4α.84-419 construct has peen previously described (29), and the GST.HNF4α.LBD (amino acids [aa] 127 to 374) and GST.HNF4α.DBD (aa 45 to 125) constructs are described elsewhere (38). The GST.HNF4α.LBD/F (aa 127 to 455), GST.HNF4α.DBD/H (aa 45 to 142), and GST.HNF4.Fαl constructs were created by using the appropriate primers containing EcoRI (sense) or XhoI (antisense) sites to generate PCR fragments corresponding to the appropriate amino acids of rat HNF4α1. Each of these fragments was then ligated into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of the pGEX.6P-1 vector (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). All GST.SMRT fusion constructs were described previously (70). The pSG5.Gal4DBD, pSG5.Gal4DBD.SMRT (aa 1 to 1495), pSG5.Gal4DBD.SMRT.RID2 (aa 1291 to 1495), and pM.Gal4DBD.GRIP1 (aa 5 to 1462) constructs have all been described previously (33, 70). The pVP16AD.GRIP1.NR (aa 322 to 1121) (VP16.GRIP1.NR) and pVP16AD.C-GRIP1 (aa 1122 to 1462) (VP16.GRIP1.C) constructs were generous gifts from M. Stallcup. The luciferase reporter construct pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4, containing four tandemerized HNF4α response elements from the human apolipoprotein AI gene, has been previously described (55), as has the luciferase reporter ApoB.Luc, which contains the EcoRI/HindIII fragment spanning nucleotides −262 to +122 of the human apolipoprotein B gene (8). The reporter construct ApoCIII.Luc was generated by excising the 845-bp KpnI/HindIII fragment, corresponding to nucleotides −821 to +24 of the human apolipoprotein CIII gene, from pMU (34) and ligating it into pZLuc (54), which was cut with KpnI and HindIII. All PCR products were verified by dideoxy sequencing.

Transient-transfection assays.

All cell lines were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin and 5% fetal calf serum. The hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Hep3B, the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2, and the African green monkey kidney cell line CV-1 were all maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1% nonessential amino acids, and 10, 20, and 10% fetal bovine serum, respectively. All transfections were carried out in six-well plate format with 35-mm-diameter wells. Cells were seeded 1 day prior to transfection at the following densities to yield approximately 50 to 70% confluency at the time of transfection: 293T cells, 0.375 × 106/well; Hep3B and Caco-2 cells, 0.5 × 106/well; CV-1 cells, ∼0.15 × 106/well. Transfections were carried out via calcium phosphate precipitation essentially as previously described (55) or with Lipofectin (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol as indicated. The appropriate amount of empty vector(s) (e.g., pMT7 for pMT7.HNF4 constructs or pSG5 for pSG5.SMRT and pSG5.GRIP1 constructs) was added to keep the amounts of DNA equal in each well. Transfected 293T cells were harvested 24 h post glycerol shock/medium change, except for those in the experiments in Fig. 6B and C, which were harvested at 40 h. All other transfected cells were harvested at 40 h. Trichostatin A (TSA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and light-isomerized RA (RA + light) (29) were added as indicated; wells lacking these additives were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (for TSA) or ethanol (for RA). Results of one representative experiment of several are presented as fold induction of relative light units normalized to β-galactosidase activity relative to that observed for the empty vectors and the reporter alone. Error bars indicate 1 standard deviation from the average of the triplicate samples in one experiment.

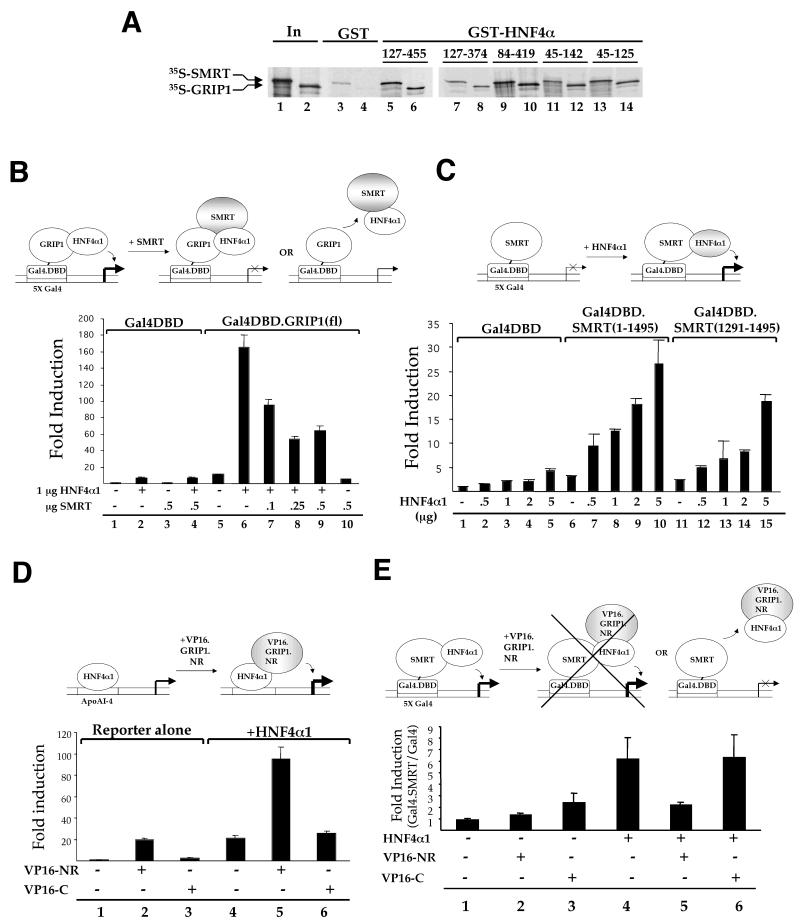

FIG. 6.

Competition between SMRT and GRIP1 for modulation of HNF4α1 activity results from mutually exclusive binding. (A) Pulldown assay with the indicated immobilized GST.HNF4α proteins (numbers indicate amino acids in HNF4α1 [Fig. 4A]) and 35S-SMRT or 35S-GRIP1 as in Fig. 3B. (B) Transient transfections into 293T cells with calcium phosphate and 2 μg of pFR.Luc (Gal4 reporter), 0.5 μg of RSV.βgal, 0.5 μg of either Gal4.DBD or pM.Gal4DBD.GRIP1(fl) (aa 5 to 1462), 1 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, and increasing amounts of pSG5.SMRT as indicated. Top, schematic diagram of factors used in the assay and interpretation of the results. (C) Transient transfections as in panel B but with 0.5 μg of either Gal4DBD, pSG5.Gal4DBD.SMRT(1-1495), or Gal4DBD.SMRT(1291-1495) (RID2) and increasing amounts of pMT7.HNF4α1 as indicated. Top, as in panel B. (D) Transient transfections as in panel B but using Lipofectamine and with 1 μg of pZLHIV.AI-4, 0.1 μg of CMV.βgal, 0.2 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, and 1 μg of VP16.GRIP1.NR (aa 322 to 1121) (VP16-NR) or VP16.GRIP1.C (aa 1122 to 1495) (VP16-C) as indicated. Top, as in panel B except that the control, VP16.GRIP1.C, is not shown as it does not interact with HNF4α1. (E) Transient transfections as in panel D but with 0.2 μg of pFR.Luc, 0.1 μg of CMV.βgal, 0.0125 μg of Gal4DBD, or 0.025 μg of pSG5.Gal4DBD.SMRT(1-1495) (molar equivalent of Gal4DBD), 1 μg of VP16.GRIP1.NR (VP16-NR) or VP16.GRIP1.C (VP16-C), and 0.2 of μg pMT7.HNF4α1 as indicated. Shown is the fold induction calculated as the relative light units normalized to β-galactosidase for the Gal4DBD.SMRT fusion construct divided by the corresponding value observed for the Gal4DBD vector alone, from one of four representative experiments done in triplicate. Error bars indicate the largest percent error, determined as 1 standard deviation of triplicate samples from either the Gal4DBD or Gal4DBD.SMRT data and applied to the fold induction shown (Gal4DBD.SMRT/Gal4DBD). Top, as in panel D.

GST pulldown assays.

All protein-protein interactions analyzed by the glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay were performed essentially as previously described (55). Briefly, approximately 10 μg of GST or GST fusion proteins expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3)pLysS were immobilized on agarose beads (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and incubated with 2 to 4 μl of in vitro-translated, 35S-methionine-labeled proteins made in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate kit (TNT; Promega, Madison, Wis.), washed extensively, eluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), visualized via autoradiography, and quantified (where indicated) via phosphorimaging analysis (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Where indicated, myristoyl-coenzyme A thioester (C:14-CoA; Sigma) was dissolved in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.98) and added to both the HNF4α1-programmed lysate and GST fusion proteins to the indicated final concentration 20 min prior to the pulldown reaction. Sodium acetate alone was added to samples lacking C:14-CoA. All assays were performed at least three independent times, and the most representative results are shown.

RESULTS

Corepressor SMRT represses HNF4α1 transcriptional activity in vivo.

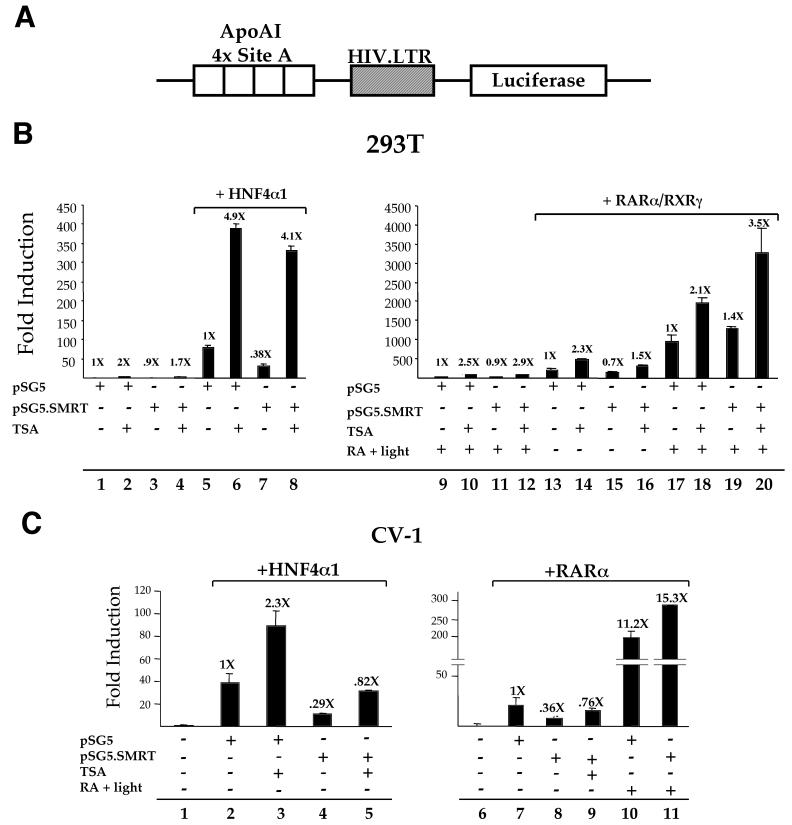

To determine whether SMRT could repress HNF4α1 transcriptional activity, full-length HNF4α1, SMRT, and a luciferase reporter construct responsive to both HNF4α1 and retinoid receptors (Fig. 1A) were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells, which do not possess detectable levels of endogenous HNF4α1 protein (38). As indicated in Fig. 1B, cotransfection with the SMRT expression vector had a negligible effect on transcription from the reporter alone (compare lane 3 to lane 1) but a substantial effect on HNF4α1-mediated transcription (lane 7 versus lane 5), as well as the RAR/RXR control (lane 15 versus lane 13). To determine whether recruitment of HDAC activity was involved in the repression of HNF4α1 by SMRT as it is for other nuclear receptors, the specific inhibitor TSA was added. TSA stimulated the reporter alone marginally (compare lane 2 to lane 1) but had a much greater effect on HNF4α1-mediated transcription (lane 6 versus lane 5). Not only was the absolute increase in transcription greater, but the relative change in the fold induction was also greater for HNF4α1-mediated transcription than for the basal transcription (4.9-fold versus 2-fold, respectively). Furthermore, TSA nearly completely reversed the ability of SMRT to repress HNF4α1-mediated transcription in this experiment (lane 8), suggesting that recruitment of HDAC activity is involved in the repression. As expected, TSA had a similar effect on repression of RAR/RXR by SMRT in the absence of a ligand (lanes 14 and 16). In the presence of a ligand, TSA was still able to stimulate RAR/RXR-mediated transcription both in the absence and in the presence of cotransfected SMRT (lanes 18 and 20), suggesting either that the ligand added was not sufficient to dislodge a SMRT-HDAC complex or that TSA had an additional effect on transcription. Others have also reported that TSA can enhance the effect of RA treatment (45). Finally, whereas repression of RAR/RXR activity by SMRT is typically demonstrated by using Gal4 fusion constructs, we observed significant repression of this RA-responsive reporter in both HEK 293T and CV-1 cells. This could be due to the nature of the DNA binding element in the reporter construct, as corepressors have been shown to be highly selective of DNA-bound receptors (74) and/or the cell type.

FIG. 1.

SMRT represses the transcriptional activity of transfected HNF4α1. (A) Schematic representation of the pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc reporter construct. Shown are the four tandemerized site A elements from the human apolipoprotein AI promoter, which is responsive to both HNF4α1 and RARα/RARγ, linked to the firefly luciferase gene driven by the promoter from the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat (HIV.LTR; −57 to +80). (B) Transient transfection into 293T cells using Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL) with 0.7 μg of pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc, 0.1 μg of CMV.βgal, either 0.25 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1 or 0.125 μg of pCMX.hRARα plus 0.125 μg of pCMX.mRXRγ, and 0.05 μg of pSG5.SMRT or the molar equivalent of pSG5 as indicated and as described in Materials and Methods. After removal of the Lipofectamine-DNA mixture, all cells were incubated in medium plus 5% stripped serum (CPSR1; Sigma). TSA at 100 ng/ml or 20 μM RA + light was added in medium with stripped serum 16 h later (8 h prior to harvest) as indicated. Note the difference in scale on the y axes. Values above the bars indicate the activity relative to that observed in the presence of the pSG5 vector alone, defined as 1×. (C) Transient transfection into CV-1 cells using Lipofectin with 2 μg of pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc, 0.5 μg of RSV.βgal, 1 μg of either pMT7.HNF4α1 or pCMX.RARα, and 1 μg of pSG5.SMRT or the pSG5 empty vector, as indicated. Addition of either TSA at 10 ng/ml or 1 μM RA + light 20 h prior to harvest is indicated.

A similar series of experiments was performed in another non-HNF4α1-expressing cell line, CV-1 (Fig. 1C). SMRT also substantially repressed HNF4α1-mediated transcription in CV-1 cells (lane 4 versus lane 2), and the repression was reversed by addition of TSA to a level similar to that for transfected RARα (lanes 5 and 9). The lack of complete reversal of SMRT repression by TSA in this and other experiments (not shown) could be due to an HDAC-independent mechanism of repression, such as SMRT interaction with transcription factor IIB (TFIIB), as has been reported previously (70). Finally, a lack of repression by SMRT of RARα in the presence of a ligand (lane 11 versus lane 10) confirmed once again that the repression observed is due to a specific mechanism and is not due to a general inhibitory effect of the SMRT vector.

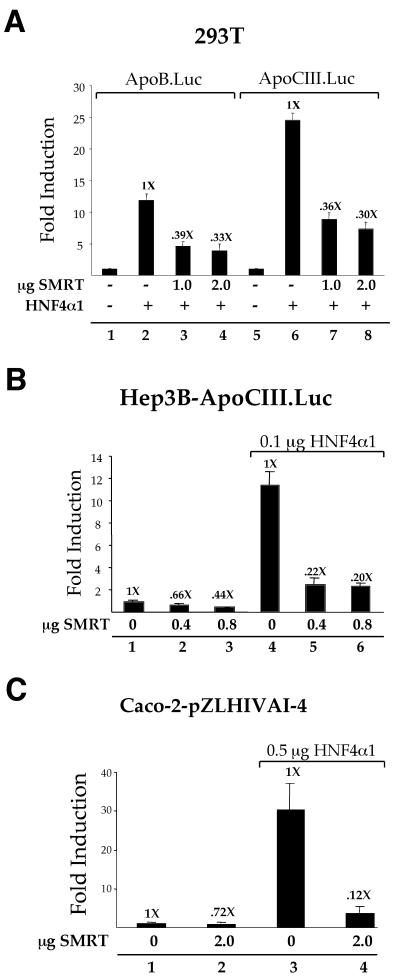

In order to verify that SMRT represses HNF4α1-mediated transcription under more physiological conditions, cotransfections with reporter constructs containing native promoters (ApoB.Luc and ApoCIII.Luc) were first performed with 293T cells. The results indicate that SMRT was able to substantially repress HNF4α1 activity on both of these reporters (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 3 and 4 to lane 2 and lanes 7 and 8 to lane 6), suggesting that SMRT may function as a repressor of HNF4α1-dependent transcription on a variety of natural HNF4α1 target genes. To determine whether SMRT could repress the transcriptional activity of HNF4α1 in HNF4α1-expressing cell lines, cotransfections were performed with Hep3B and Caco-2 cells, both of which express moderate-to-high levels of HNF4α1 (data not shown). Cotransfected SMRT repressed endogenous HNF4α1 transcriptional activity by approximately 56% in Hep3B cells (Fig. 2B, lane 3) and 28% in Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2C, lane 2), while exogenously expressed HNF4α1 was repressed by approximately 80% in Hep3B cells (Fig. 2B, lane 6) and 88% in Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2C, lane 4). The only cell line tested in which SMRT did not repress HNF4α1 activity was HepG2, but RARα activity was also not affected (data not shown) and the lack of repression could be due to an altered signaling pathway in those cells (23, 25).

FIG. 2.

SMRT represses HNF4α1 activity on native promoter constructs and in HNF4α-expressing cell lines. (A) Transient transfection into 293T cells using Lipofectamine with 0.4 μg of the indicated luciferase reporter constructs, 0.1 μg of CMV.βgal, 0.1 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, and the indicated amounts of pSG5.SMRT. All samples have equivalent molar amounts of the pSG5 vector. Values indicate relative fold induction to show the effect of SMRT on HNF4α1. (B) Transient transfection into Hep3B cells using Lipofectamine with 0.8 μg of ApoCIII.Luc, 0.1 μg of CMV.βgal, 0.1 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, andpSG5.SMRT as indicated. (C) Transient transfection into Caco-2 cells using calcium phosphate with 2 μg of pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc, 0.5 μg of RSV.βgal, 0.5 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, and 2.0 μg of pSG5.SMRT as indicated.

HNF4α1 interacts directly with SMRT in vitro.

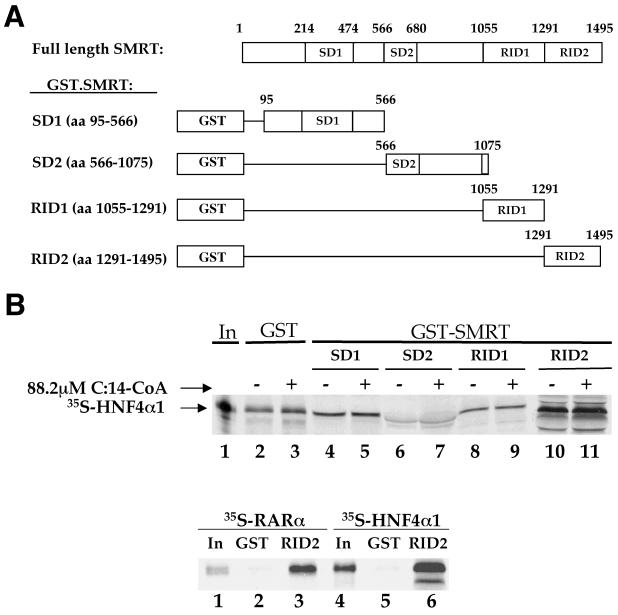

To determine whether HNF4α1 interacts directly with SMRT, GST fusion constructs spanning the length of the SMRT polypeptide (Fig. 3A) were tested for the ability to interact with in vitro-translated, 35S-labeled HNF4α1. Parallel samples were incubated in the presence or absence of C:14-CoA, one of a class of recently proposed activating ligands for HNF4α1 (21). The results indicate that the SMRT construct containing C-terminal receptor interacting domain 2 (RID2) was the only one to bind to HNF4α1 above background levels (Fig. 3B, compare lane 10 to lane 2). The presence of C:14-CoA did not affect binding to RID2 (lane 11) or binding to the other GST.SMRT constructs, indicating that this compound cannot facilitate corepressor release from HNF4α1. This further supports the notion that these compounds do not act as bona fide ligands (3), although the correlation between release from a corepressor in vitro and the ability to activate transcription in vivo is not absolute (11). Interaction of GST.SMRT.RID2 with 35S-labeled RARα served as a positive control for HNF4α1 binding; both RARα and HNF4α1 bound at approximately 25% (Fig. 3C). Roughly 40% of the RARα binding was released in the presence of a ligand (data not shown). Whereas RARα has been reported by several groups to preferentially bind RID1 of SMRT and N-CoR, those groups also reported some binding to RID2 (26, 27, 36).

FIG. 3.

HNF4α1 and SMRT interact directly. (A) Schematic diagram of GST.SMRT fusion proteins used in protein interaction assays. Full-length SMRT corresponds to the amino acid sequence in the original SMRT cDNA (6). SD1, silencing domain 1; SD2, silencing domain 2. Numbers indicate amino acid residues. (B) Pulldown assay with the indicated immobilized GST fusion proteins and in vitro-translated, 35S-labeled-HNF4α1 in the presence of C:14-CoA (+) or solvent (−) as indicated and as described in Materials and Methods. The background binding to GST was somewhat elevated due to the sodium acetate used to dissolve the C:14-CoA. In the absence of sodium acetate, the RID2 construct was also the only one to significantly bind HNF4α1 (see Fig. 4C; data not shown). Shown are autoradiographs of SDS-10% PAGE from a representative of several experiments. In, 10% of the total input lysate. (C) Pulldown assays as in panel B but with 35S-labeled-RARα and HNF4α1 and GST.SMRT.RID2 and in the absence of added ligand. In, 5% of the total input lysate.

The F domain modulates the ability of SMRT to repress HNF4α1 activity.

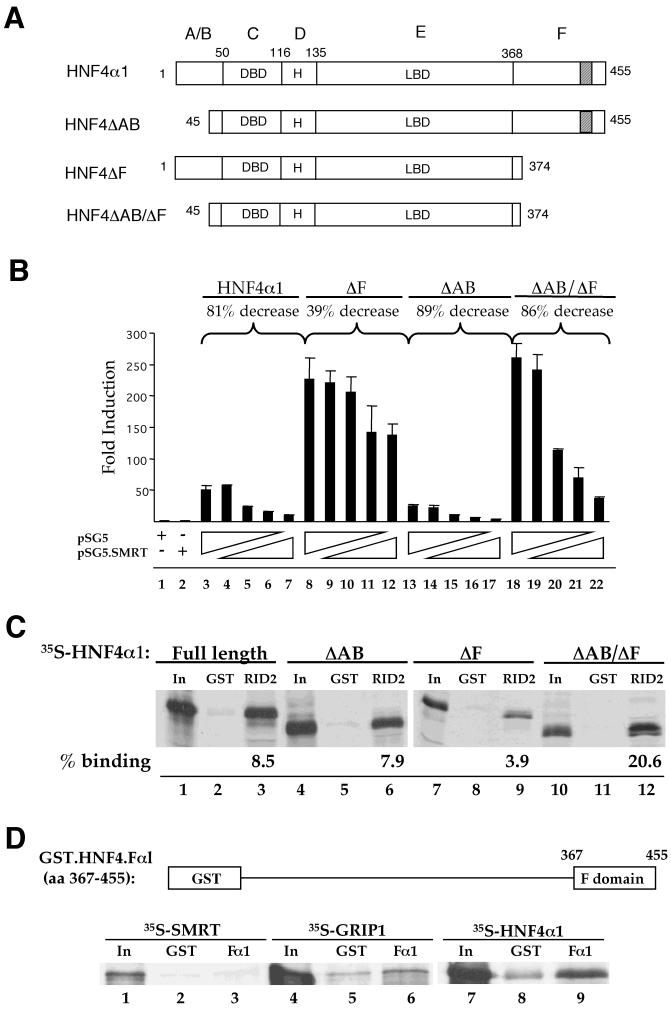

We and others previously identified the C-terminal F domain as possessing a negative regulatory function with respect to coactivation by CBP and GRIP1 (28, 55). To investigate whether the F domain may also play a role in corepressor recruitment, 293T cells were cotransfected with either full-length HNF4α1 or one of three deletion constructs lacking either the N or C terminus or both (Fig. 4A) and increasing amounts of the SMRT vector. The efficacy of SMRT repression for each construct was then determined as the percent decrease in fold induction measured at the greatest amount of SMRT vector compared to that measured with no SMRT vector added. SMRT-mediated repression of the N-terminally truncated construct (ΔAB) was almost identical to that observed for full-length HNF4α1 (Fig. 4B, 89% decrease versus 81% decrease; compare lanes 13 to 17 to lanes 3 to 7). In contrast, the C-terminal HNF4α deletion construct (ΔF) was less than one-half as susceptible to SMRT repression as was full-length HNF4α1 (39% decrease; lanes 8 to 12). Surprisingly, the double-truncation construct (ΔAB/ΔF) was repressed by SMRT as well as the full-length and ΔAB constructs (86% decrease; lanes 18 to 22).

FIG. 4.

The F domain of HNF4α1 is required for full interaction with SMRT in vivo and in vitro. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length wt rat HNF4α1 and the various HNF4α deletion constructs used. Numbers indicate amino acids. Letters at the top indicate conventional nuclear receptor domains. H, hinge region; shaded section, repressor region (28). (B) Transient transfection into 293T cells using calcium phosphate with 2 μg of pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc, 0.5 μg of RSV.βgal, 1.0 μg each of the indicated pMT7.HNF4α vectors, and either 0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, or 0.2 μg of pSG5.SMRT or pSG5 (indicated by ramps); +, addition of 0.2 μg of pSG5 or pSG5.SMRT. Percent decrease refers to the difference in the fold induction observed at the maximal SMRT dose versus that observed with the pSG5 empty vector alone (e.g., lane 7 versus lane 3). (C) Pulldown assay with immobilized GST.SMRT.RID2 protein (RID2) as in Fig. 3. Shown are autoradiographs of SDS-8% PAGE. Percent binding, percentage of the HNF4α construct bound less that observed for the GST control as determined by phosphorimaging analysis. (D) Pulldown assay with immobilized GST.HNF4.Fα1 and in vitro-translated 35S-SMRT, 35S-GRIP1, or 35S-HNF4α1 as indicated and as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

In order to determine whether the differential responsiveness of the HNF4α constructs in vivo might be due to differential binding to SMRT, pulldown assays utilizing GST.SMRT.RID2 and each of the HNF4α deletion constructs were performed. The results indicate that the construct lacking the F domain (ΔF) bound SMRT significantly less well than did full-length HNF4α1 and the construct lacking the AB domain (Fig. 4C, compare lane 9 to lanes 3 and 6, respectively). Importantly, loss of both the A/B and F domains completely restored optimal interaction with SMRT (lane 12), reflecting the rescued responsiveness of this construct to SMRT in vivo. In fact, the interaction with the ΔAB/ΔF construct was consistently greater than that with the wild-type (wt) construct (20.6 versus 8.5% in Fig. 4C), which is consistent with the greater absolute repression of this construct by SMRT in vivo (Fig. 4B, from 260-fold induction to 40-fold induction for ΔAB/ΔF versus 50-fold induction to 10-fold induction for the wt).

Pulldown experiments utilizing a GST fusion protein containing just the F domain of HNF4α1 (GST.HNF4.Fα1) incubated with 35S-labeled SMRT or 35S-labeled GRIP1 indicated that the isolated F domain did not interact to any appreciable degree with either of these cofactors (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 3 and 6 to lanes 2 and 5). Since our previous results showed that the F domain interacts with another portion of HNF4α1 (55), a pulldown assay was done with 35S-labeled HNF4α1 to verify that the F domain moiety of the fusion protein had adopted a functionally competent conformation. The results show that the GST.HNF4.Fα1 construct did interact somewhat above the background level with 35S-labeled HNF4α1 (compare lane 9 to 8). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that the F domain plays a crucial facilitative role in the ability of full-length HNF4α1 protein to interact with SMRT both in vivo and in vitro, although it does not appear to interact directly with either SMRT or GRIP1 on its own.

Corepressor SMRT competes with coactivators and cointegrators for modulation of HNF4α1 activity.

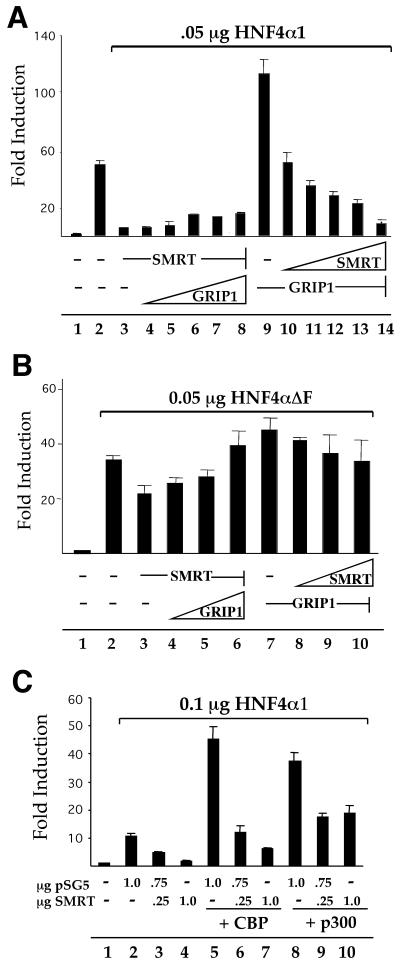

The results thus far, in concert with our previous work, argue that HNF4α1 can functionally interact both in vivo and in vitro with both corepressor SMRT and the coactivators GRIP1, CBP, and p300 without changing the status of any putative endogenous ligand. Therefore, given the conceptual difficulty of envisioning any such ligand as simultaneously functioning as both a positive and negative regulator of HNF4α1 function, it seemed plausible that the coactivation and corepression effects observed may not depend on the existence of a ligand. To test this idea directly, both GRIP1 and SMRT were assayed for the ability to compete for the modulation of HNF4α1 activity in vivo. Constant amounts of GRIP1 or SMRT were cotransfected into 293T cells with increasing amounts of SMRT or GRIP1, respectively, along with a minimal amount of HNF4α1. The results show that whereas GRIP1 coactivated HNF4α1 in the absence of transfected SMRT (Fig. 5A, compare lane 9 to lane 2), the coactivation was drastically abated when SMRT was added to the transfection; nearly all of the GRIP1 coactivation was lost upon addition of the least amount of SMRT (lane 10). Increasing amounts of cotransfected SMRT continued to decrease the HNF4α1-mediated transcription, with the maximum amount of SMRT resulting in nearly basal levels of transcription (compare lanes 10 to 14 to lane 1). In contrast, the maximum amount of GRIP1 reversed only a modest amount of the HNF4α1 activity that was repressed by the addition of SMRT (compare lane 8 to lanes 2 and 3). Strikingly, in identical experiments utilizing the F domain deletion construct (HNF4ΔF), the maximum amount of SMRT did not repress HNF4ΔF activity in the presence of GRIP1 to any significant degree (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 8 to 10 to lane 7). However, GRIP1 was able to fully reverse the modest repression of this construct by SMRT (compare lanes 4 to 6 to lane 3). Experiments in which SMRT was cotransfected with either CBP or p300 showed a similar ability of SMRT to compete with these cointegrators for modulation of HNF4α1 activity in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 to 7 and 8 to 10). We conclude that SMRT can actively compete with coactivators/cointegrators for HNF4α1 activity and that the competitive strength of SMRT is critically dependent on the presence of the F domain.

FIG. 5.

Competition between corepressor SMRT and coactivators for HNF4α1 activity in vivo: modulation by the F domain. (A) Competition between SMRT and GRIP1 for regulation of HNF4α1 activity. 293T cells were transiently transfected by using calcium phosphate with 2 μg of pZL.HIV.LTR.AI-4.Luc, 0.5 μg of RSV.βgal, 0.05 μg of pMT7.HNF4α1, and either 0.3 μg of pSG5.SMRT plus 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, or 0.3 μg of pSG5.GRIP1 (lanes 2 through 8) or 0.3 μg of pSG5.GRIP1 plus 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, or 0.3 μg of pSG5.SMRT (lanes 9 through 14). (B) Effect of loss of the F domain of HNF4α1 onin vivo competition between SMRT and GRIP1. 293T cells were transfected as in panel A, except that the pMT7.N1C374 (HNF4αΔF) construct was used in place of pMT7.HNF4α1 and that 0.25 μg of pSG5.SMRT was used with 0, 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 μg of pSG5.GRIP1 (lanes 3 through 6) or 0.25 μg of pSG5.GRIP1 with 0, 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 μg of pSG5.SMRT (lanes 7 through 10). (C) Dose-dependent repression of CBP and p300 coactivation of HNF4α1 by SMRT. 293T cells were transfected as in panel A with the indicated amounts of HNF4α1, CBP, p300, and SMRT expression vectors. Empty expression vectors were added as appropriate.

GRIP1 and SMRT bind multiple overlapping regions of HNF4α1 in vitro and actively compete for binding in vivo.

The in vivo competition data suggested that both a coactivator and a corepressor may actively compete for binding to common or overlapping regions of HNF4α1. To determine which region(s) of HNF4α1 binds the cofactors, pulldown assays were performed with various GST.HNF4α constructs and 35S-labeled SMRT and GRIP1. The results show that both 35S-GRIP1 and 35S-SMRT bound GST.HNF4α constructs containing just the LBD and the C-terminal part of the hinge (aa 127 to 374) (Fig. 6A, lanes 7 and 8; see Fig. 4A for domain structure) or just the DBD and the N-terminal part of the hinge (aa 45 to 125) (lanes 13 and 14) and a construct spanning part of the DBD through part of the F domain (aa 84 to 419) (lanes 9 and 10). These results indicate that there are at least two regions in HNF4α1 that interact with both a coactivator and a corepressor, one in the DBD/hinge domain (aa 45 to 125) and one in the LBD/hinge domain (aa 127 to 374). The region in the LBD could be helices 3 and 4, which contain the conserved residues found in TRα and RXRα that are known to be critical for corepressor and coactivator binding (26). Binding of regions outside the LBD to corepressors is less common and less well defined but has been noted in at least two other receptors, PPARα and RARα (11, 36).

Whereas these results suggested that the competition observed in vivo could be due to active competition between the two cofactors for occupancy of a common docking surface in HNF4α1 (i.e., mutually exclusive binding of SMRT and GRIP1 to HNF4α1), other explanations were also possible. For example, there could be a ternary complex containing a corepressor, a coactivator, and HNF4α1, in which the activity of the corepressor negates any activity of the coactivator. Alternatively, there could be a passive competition in which there are two subpopulations of HNF4α1-reporter units, one tethered to a coactivator and the other tethered to a corepressor. To distinguish among these three scenarios, we employed Gal4DBD fusion constructs in modified mammalian one- and two-hybrid assays. In the one-hybrid assay, we found that HNF4α1 transactivated a Gal4DBD.GRIP1 construct to a large degree (Fig. 6B, compare lane 6 to lane 5), indicating that HNF4α1 could either recruit additional coactivators to Gal4-GRIP1 and/or provide a bridge between Gal4-GRIP1 and the basal transcription machinery. As we anticipated, cotransfection with full-length SMRT substantially decreased the transactivation by HNF4α1 in a dose-dependent fashion (lanes 7 to 9). These results argue against the third scenario, in which the competition is passive, and suggest that there is a direct interaction among HNF4α1, GRIP1, and SMRT. However, they do not discriminate between the two remaining scenarios-formation of a ternary complex of GRIP1-HNF4α1-SMRT and active competition due to mutually exclusive binding to HNF4α1 (diagrammed in Fig. 6B, top).

In order to distinguish between these two scenarios, we designed an experiment in which HNF4α1 was tethered to a Gal4-SMRT construct and tried to remove it by competition with a VP16.GRIP1 construct. We first verified that HNF4α1 could activate transcription while bound to a Gal4-SMRT construct in a dose-dependent fashion for both a Gal4DBD fusion containing full-length SMRT and one containing just RID2 (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 7 to 10 to lane 6 and lanes 12 to 15 to lane 11, respectively). These results also confirmed that HNF4α1 interacts with SMRT via RID2 in vivo, as well as in vitro. The transactivation by HNF4α1 tethered to Gal4-SMRT was presumably due to factors that do not compete with SMRT. The AB domain of HNF4α1, for example, has been found to interact with components of the basal transcription machinery, such as TATA binding protein, TATA binding protein-associated factors 31 and 80, and TFIIB and TFIIH-p62, as well as non-p160 coactivators such as ADA2, PC4, and CBP (17). To verify that the VP16-GRIP1 construct would stimulate transcription when tethered to HNF4α1, we used the reporter with HNF4α1 binding sites (as in Fig. 1A) and two VP16-GRIP1 constructs, one harboring the NR boxes known to mediate interaction with HNF4α1 (VP16.GRIP1.NR) (55) and, as a control, a Gal4-GRIP1 fusion that contained the C-terminal region of GRIP1 but not the NR boxes (VP16.GRIP1.C). The results show that VP16.GRIP1.NR activated transcription on the reporter alone, verifying the ability of this construct to stimulate transcription (Fig. 6D, lane 2 versus lane 1). In the presence of HNF4α1, the VP16.GRIP1.NR construct stimulated transcription even further, verifying its ability to interact with HNF4α1 and further enhance transcription (lane 5 versus lane 4). The VP16.GRIP1.C control showed negligible activity on this reporter both in the absence and in the presence of HNF4α1, confirming its utility as a negative control (lanes 3 and 6 versus lanes 1 and 4). The activity of VP16.GRIP1.NR on the reporter in the absence of HNF4α1 could be due to stimulation of endogenous retinoid receptors known to bind to this reporter (Fig. 1).

Finally, we employed a modified two-hybrid system in which the Gal4DBD.SMRT (full length) was cotransfected with HNF4α1 and the VP16-GRIP1 fusion construct. We reasoned that formation of a ternary complex would result in a level of stimulation of transcription above that achieved by Gal4DBD.SMRT plus HNF4α1 alone due to the presence of the VP16 activation domain fused to GRIP1. In contrast, if GRIP1 binding to HNF4α1 and SMRT binding to HNF4α1 were mutually exclusive, then we anticipated that addition of VP16.GRIP1.NR would result in a decrease in activity as a result of sequestration of HNF4α1 from Gal4DBD.SMRT. The latter is indeed what we observed (Fig. 6E, compare lane 5 to lane 4, see also diagram at the top), suggesting that this GRIP1 construct was able to actively compete for HNF4α1 binding. In contrast, the VP16.GRIP1.C construct did not reduce the luciferase activity (compare lane 6 to lane 4), suggesting that the competition observed with the GRIP1.NR fusion was due to competition for binding and not due to squelching of the transcription apparatus by the VP16 moiety. Similar results were observed with the Gal4DBD.SMRT (aa 1291 to 1495) construct (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that GRIP1 and SMRT can actively compete with each other and bind to HNF4α1 in vivo in a mutually exclusive manner and that this can occur in the absence of an exogenously added ligand.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that the transcriptional activity of HNF4α1, previously characterized by us and others as a constitutive activator of transcription, can be actively repressed by the corepressor SMRT (Fig. 1). We show that repression occurs in HNF4α1-expressing and -nonexpressing cell lines and on heterologous, as well as native, promoters, suggesting that the repressive effect may be a physiologically relevant mode of regulation of HNF4α1 activity (Fig. 2). We found that, like that by other nuclear receptors, repression by SMRT is reversed by TSA (Fig. 1) and that HNF4α1 interacts directly with SMRT exclusively via the RID2 domain (Fig. 3). However, unlike previous reports for other nuclear receptors with identified ligands, we found that addition of a ligand is not required for the switch between corepressor SMRT and coactivator GRIP1, CBP, or p300 (Fig. 5). Rather, SMRT appears to compete directly with GRIP1 for interaction with HNF4α1 (Fig. 6). Furthermore, we found that the abilities of SMRT to repress HNF4α1 in vivo and to interact in vitro are significantly diminished by removal of the F domain of HNF4α1 while removal of both the A/B and F domains restores optimal interaction (Fig. 4 and 5).

The F domain modulates access to the cofactor docking surface in a non-ligand-dependent fashion.

The current model for nuclear receptor function is that, in the absence of a ligand, the receptor binds a corepressor and then, upon ligand binding, the receptor undergoes a conformational change that displaces the corepressor and recruits coactivators. There is a good deal of evidence for all aspects of this model, including reports that show that regions within the LBD critical for coactivator interaction are also important for corepressor recruitment. Thus, it appears that a common, or at least overlapping, docking surface exists that includes numerous cofactor contact points and that an equilibrium exists between the competency of this surface for corepressor recruitment and its competency for coactivator recruitment, an equilibrium that is altered by the presence or absence of a ligand (26, 46, 51). The evidence presented here suggests that such a docking surface also exists for HNF4α1 (Fig. 6A) but that, in contrast to other receptors, competition for access to the docking surface of HNF4α1 may not be regulated in a traditional ligand-dependent fashion (Fig. 5 and 6). Rather, since our data show that the presence of the F domain critically affects both responsiveness to (Fig. 4B and C and reference 55) and discrimination between (Fig. 5A and B) corepressors and coactivators, we propose that the F domain may act in a fashion similar to that of a traditional ligand. The finding that the F domain itself fails to interact directly with either SMRT or GRIP1 in vitro (Fig. 4D) suggests that the F domain modulates access to the docking surface allosterically rather than by directly binding to cofactors. Finally, it is of interest that the increase in activity observed upon removal of the F domain—up to 30-fold relative to that obtained with the full-length receptor—approximates the ligand-induced increase observed for many bona fide ligand-dependent receptors (29).

With RXRα, it has been proposed that AF-2 (helix 12) blocks the corepressor binding site since the interaction with corepressors increases dramatically when it is deleted (27, 75). One could postulate, then, that the F domain of HNF4α prevents AF-2 from blocking the corepressor binding site and that deletion of the F domain allows AF-2 to fully inhibit binding to corepressors. Consistent with this model is the fact that deletion of AF-2 from HNF4ΔF enhances binding to SMRT in vitro, although not as drastically as it does for RXRα (data not shown). Furthermore, the computer graphic model of the HNF4α LBD juxtaposes the N-terminal portion of the F domain next to the putative conserved helix 3-4-5 corepressor binding site, making interaction between the two regions a possibility (3). However, any such model would have to factor in the effect of deletion of the AB domain of HNF4α, which restores binding to and repression by SMRT (Fig. 4), as well as the fact that there are additional SMRT binding sites in HNF4α in the DBD/hinge domain (Fig. 6). Also, it is proposed that AF-2 of RXRα is repositioned by binding to its heterodimeric partner, thereby unmasking the corepressor binding sites (75). Whereas RXRα is the receptor most similar to HNF4α in terms of amino acid sequence (48) and DNA binding specificity (56), it does not contain an F domain. Furthermore, HNF4α does not heterodimerize with RXRα or with any other known receptor (3, 29), so one must postulate that factors unique to HNF4α alter the position of the F domain.

Potential role of the AB domain of HNF4α in corepressor activity.

It has been shown for many nuclear receptors that N-terminal AF-1 can interact with AF-2, as well as with several coactivators, providing both cooperative and independent roles for each AF in the transcriptional output of these receptors (2, 16, 18, 50, 62). AF-1 of HNF4α1 has also been shown to interact with several coactivators and components of the general transcription machinery and to contribute to the transcriptional activity of the receptor (9, 17). Our present observation that removal of the A/B domain, which contains AF-1, restores full responsiveness of HNF4ΔF to SMRT (Fig. 4) suggests that the A/B domain also influences corepressor recruitment in a manner that antagonizes the action of the F domain. However, additional studies are required to determine whether the antagonism involves a direct interaction between the A/B and F domains or whether it involves manipulation of the common docking surface and its accessibility to a corepressor.

Other nonligand modulators of nuclear receptor activity.

There is precedence for the notion that factors other than ligand status modulate the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors. For example, several nuclear receptors are known to receive alternative signals, such as phosphorylation and acetylation, that alter the ability to interact with coregulatory molecules and modulate transcription (15, 18, 62, 67, 68). Such signals, in addition to the F domain, may also play a role in HNF4α1 function, as HNF4α1 has been shown by others to be acetylated (59) and by us to be phosphorylated (30). Indeed, we and others have shown that the F domain may be phosphorylated although the function of that phosphorylation is not known (M. D. Ruse, Jr., unpublished data; T. Leff, personal communication). It will be of interest to determine whether the A/B domain might also serve as a substrate for phosphorylation in vivo and whether such a modification might affect the properties of this region of the receptor.

Another potential mode of regulation of the F and AB domains is alternative splicing. There are potentially nine different naturally occurring HNF4α isoforms that differ in the A/B and F domains (56). We showed previously that the HNF4α2 isoform, which contains a 10-aa insertion in the F domain, interacts more efficiently with coactivator GRIP1 in vitro and responds about sevenfold better in vivo. We also provided evidence that, as a direct result of the 10-aa insertion, there is an alteration in the proposed intramolecular interaction between the F domain and the remainder of the receptor (55). Some of the other HNF4α isoforms have been shown to exhibit transactivation potentials different from that of HNF4α1 (47); however, a correlation between transcriptional activity and cofactor recruitment has not been established for these other isoforms and little is known about the physiological relevance of the diversity of HNF4α gene products. Nonetheless, it is enticing to speculate that this diversity may serve to generate even more diverse regulatory domains with differing affinities for cofactors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Maeda and M. Mittal for GST.HNF4α constructs, M. Stallcup for GRIP1 constructs, R. Goodman for CBP, and R. Evans for RAR and RXR constructs.

This research was funded by NIH grant DK 53892 to F.M.S. and NIH grant DK 53528 to M.L.P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apriletti, J. W., R. C. Ribeiro, R. L. Wagner, W. Feng, P. Webb, P. J. Kushner, B. L. West, S. Nilsson, T. S. Scanlan, R. J. Fletterick, and J. D. Baxter. 1998. Molecular and structural biology of thyroid hormone receptors. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. Suppl. 25:S2-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevan, C. L., S. Hoare, F. Claessens, D. M. Heery, and M. G. Parker. 1999. The AF1 and AF2 domains of the androgen receptor interact with distinct regions of SRC1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8383-8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogan, A. A., Q. Dallas-Yang, M. D. Ruse, Jr., Y. Maeda, G. Jiang, L. Nepomuceno, T. S. Scanlan, F. E. Cohen, and F. M. Sladek. 2000. Analysis of protein dimerization and ligand binding of orphan receptor HNF4alpha. J. Mol. Biol. 302:831-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke, L. J., and A. Baniahmad. 2000. Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 14:1876-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakravarti, D., V. J. LaMorte, M. C. Nelson, T. Nakajima, I. G. Schulman, H. Juguilon, M. Montminy, and R. M. Evans. 1996. Role of CBP/P300 in nuclear receptor signalling. Nature 383:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, J. D., and R. M. Evans. 1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377:454-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung, P., C. D. Allis, and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2000. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell 103:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas-Yang, Q., G. Jiang, and F. M. Sladek. 1998. Avoiding false positives in colony PCR. BioTechniques 24:580-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dell, H., and M. Hadzopoulou-Cladaras. 1999. CREB binding protein is a transcriptional coactivator for hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 and enhances apolipoprotein gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:9013-9021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding, X. F., C. M. Anderson, H. Ma, H. Hong, R. M. Uht, P. J. Kushner, and M. R. Stallcup. 1998. Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1): multiple motifs with different binding specificities. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:302-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell, P., J. E. Ishmael, D. Avram, V. J. Peterson, D. J. Nevrivy, and M. Leid. 1999. Identification of nuclear receptor corepressor as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha interacting protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15901-15907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckner, R., M. E. Ewen, D. Newsome, M. Gerdes, J. A. DeCaprio, J. B. Lawrence, and D. M. Livingston. 1994. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the adenovirus E1A-associated 300-kD protein (p300) reveals a protein with properties of a transcriptional adaptor. Genes Dev. 8:869-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman, L. P. 1999. Increasing the complexity of coactivation in nuclear receptor signaling. Cell 97:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman, L. P. 1999. Strategies for transcriptional activation by steroid/nuclear receptors. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 32-33:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu, M., C. Wang, A. T. Reutens, J. Wang, R. H. Angeletti, L. Siconolfi-Baez, V. Ogryzko, M. L. Avantaggiati, and R. G. Pestell. 2000. p300 and p300/cAMP-response element-binding protein-associated factor acetylate the androgen receptor at sites governing hormone-dependent transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20853-20860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelman, L., G. Zhou, L. Fajas, E. Raspé, J. C. Fruchart, and J. Auwerx. 1999. p300 interacts with the N- and C-terminal part of PPARgamma2 in a ligand-independent and -dependent manner, respectively. J. Biol. Chem. 274:7681-7688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green, V. J., E. Kokkotou, and J. A. Ladias. 1998. Critical structural elements and multitarget protein interactions of the transcriptional activator AF-1 of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29950-29957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer, G. D., I. Krylova, Y. Zhang, B. D. Darimont, K. Simpson, N. L. Weigel, and H. A. Ingraham. 1999. Phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor SF-1 modulates cofactor recruitment: integration of hormone signaling in reproduction and stress. Mol. Cell 3:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harish, S., T. Khanam, S. Mani, and P. Rangarajan. 2001. Transcriptional activation by hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 in a cell-free system derived from rat liver nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:1047-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzel, T., R. M. Lavinsky, T. M. Mullen, M. Söderstrom, C. D. Laherty, J. Torchia, W. M. Yang, G. Brard, S. D. Ngo, J. R. Davie, E. Seto, R. N. Eisenman, D. W. Rose, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hertz, R., J. Magenheim, I. Berman, and J. Bar-Tana. 1998. Fatty acyl-CoA thioesters are ligands of hepatic nuclear factor-4alpha. Nature 392:512-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong, S. H., G. David, C. W. Wong, A. Dejean, and M. L. Privalsky. 1997. SMRT corepressor interacts with PLZF and with the PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARalpha) and PLZF-RARalpha oncoproteins associated with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9028-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong, S. H., and M. L. Privalsky. 2000. The SMRT corepressor is regulated by a MEK-1 kinase pathway: inhibition of corepressor function is associated with SMRT phosphorylation and nuclear export. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6612-6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hörlein, A. J., A. M. Näär, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, B. Gloss, R. Kurokawa, A. Ryan, Y. Kamei, M. Söderström, C. K. Glass, et al. 1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu, I. C., T. Tokiwa, W. Bennett, R. A. Metcalf, J. A. Welsh, T. Sun, and C. C. Harris. 1993. p53 gene mutation and integrated hepatitis B viral DNA sequences in human liver cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis 14:987-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu, X., and M. A. Lazar. 1999. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 402:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu, X., Y. Li, and M. A. Lazar. 2001. Determinants of CoRNR-dependent repression complex assembly on nuclear hormone receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1747-1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyemere, V. P., N. H. Davies, and G. G. Brownlee. 1998. The activation function 2 domain of hepatic nuclear factor 4 is regulated by a short C-terminal proline-rich repressor domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:2098-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang, G., L. Nepomuceno, K. Hopkins, and F. M. Sladek. 1995. Exclusive homodimerization of the orphan receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 defines a new subclass of nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5131-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang, G., L. Nepomuceno, Q. Yang, and F. M. Sladek. 1997. Serine/threonine phosphorylation of orphan receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 340:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang, G., and F. M. Sladek. 1997. The DNA binding domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 mediates cooperative, specific binding to DNA and heterodimerization with the retinoid X receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1218-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knoepfler, P. S., and R. N. Eisenman. 1999. Sin meets NuRD and other tails of repression. Cell 99:447-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh, S. S., D. Chen, Y. H. Lee, and M. R. Stallcup. 2001. Synergistic enhancement of nuclear receptor function by p160 coactivators and two coactivators with protein methyltransferase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1089-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leff, T., K. Reue, A. Melian, H. Culver, and J. L. Breslow. 1989. A regulatory element in the ApoCIII promoter that directs hepatic specific transcription binds to proteins in expressing and nonexpressing cell types. J. Biol. Chem. 264:16132-16137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemon, B. D., and L. P. Freedman. 1999. Nuclear receptor cofactors as chromatin remodelers. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, H., C. Leo, D. J. Schroen, and J. D. Chen. 1997. Characterization of receptor interaction and transcriptional repression by the corepressor SMRT. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:2025-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin, R. J., L. Nagy, S. Inoue, W. Shao, W. H. Miller, Jr., and R. M. Evans. 1998. Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature 391:811-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maeda, Y., S. D. Seidel, G. Wei, X. Liu, and F. M. Sladek. 2002. Repression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α by tumor suppressor p53: involvement of the ligand binding domain and histone deacetylase activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 16:402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malik, S., W. Gu, W. Wu, J. Qin, and R. G. Roeder. 2000. The USA-derived transcriptional coactivator PC2 is a submodule of TRAP/SMCC and acts synergistically with other PCs. Mol. Cell 5:753-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malik, S., and S. K. Karathanasis. 1996. TFIIB-directed transcriptional activation by the orphan nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1824-1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mangelsdorf, D. J., U. Borgmeyer, R. A. Heyman, J. Y. Zhou, E. S. Ong, A. E. Oro, A. Kakizuka, and R. M. Evans. 1992. Characterization of three RXR genes that mediate the action of 9-cis retinoic acid. Genes Dev. 6:329-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangelsdorf, D. J., C. Thummel, M. Beato, P. Herrlich, G. Schütz, K. Umesono, B. Blumberg, P. Kastner, M. Mark, P. Chambon, et al. 1995. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marmorstein, R. 2001. Protein modules that manipulate histone tails for chromatin regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:422-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenna, N. J., J. Xu, Z. Nawaz, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1999. Nuclear receptor coactivators: multiple enzymes, multiple complexes, multiple functions. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 69:3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, D. Chakravarti, R. J. Lin, C. A. Hassig, D. E. Ayer, S. L. Schreiber, and R. M. Evans. 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89:373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, J. D. Love, C. Li, E. Banayo, J. T. Gooch, V. Krishna, K. Chatterjee, R. M. Evans, and J. W. Schwabe. 1999. Mechanism of corepressor binding and release from nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev. 13:3209-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakhei, H., A. Lingott, I. Lemm, and G. U. Ryffel. 1998. An alternative splice variant of the tissue specific transcription factor HNF4alpha predominates in undifferentiated murine cell types. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:497-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuclear Receptor Nomenclature Committee. 1999. A unified nomenclature system for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell 97:161-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogryzko, V. V., R. L. Schiltz, V. Russanova, B. H. Howard, and Y. Nakatani. 1996. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell 87:953-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Onate, S. A., V. Boonyaratanakornkit, T. E. Spencer, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, D. P. Edwards, and B. W. O'Malley. 1998. The steroid receptor coactivator-1 contains multiple receptor interacting and activation domains that cooperatively enhance the activation function 1 (AF1) and AF2 domains of steroid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12101-12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perissi, V., L. M. Staszewski, E. M. McInerney, R. Kurokawa, A. Krones, D. W. Rose, M. H. Lambert, M. V. Milburn, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1999. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev. 13:3198-3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petrij, F., R. H. Giles, H. G. Dauwerse, J. J. Saris, R. C. Hennekam, M. Masuno, N. Tommerup, G. J. van Ommen, R. H. Goodman, D. J. Peters, et al. 1995. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co-activator CBP. Nature 376:348-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shibata, H., T. E. Spencer, S. A. Oñate, G. Jenster, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1997. Role of co-activators and co-repressors in the mechanism of steroid/thyroid receptor action. Recent Prog. Hormone Res. 52:141-164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sladek, F. M., Q. Dallas-Yang, and L. Nepomuceno. 1998. MODY1 mutation Q268X in hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha allows for dimerization in solution but causes abnormal subcellular localization. Diabetes 47:985-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sladek, F. M., M. D. Ruse, Jr., L. Nepomuceno, S. M. Huang, and M. R. Stallcup. 1999. Modulation of transcriptional activation and coactivator interaction by a splicing variation in the F domain of nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6509-6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sladek, F. M., and S. D. Seidel. 2001. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α, p. 309-361. In T. Burris and E. R. B. McCabe (ed.), Nuclear receptors and genetic diseases. Academic Press, London., England.

- 57.Sladek, F. M., W. M. Zhong, E. Lai, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1990. Liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-4 is a novel member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Genes Dev. 4:2353-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sladek, R., and V. Giguère. 2000. Orphan nuclear receptors: an emerging family of metabolic regulators. Adv. Pharmacol. 47:23-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soutoglou, E., N. Katrakili, and I. Talianidis. 2000. Acetylation regulates transcription factor activity at multiple levels. Mol. Cell 5:745-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spencer, T. E., G. Jenster, M. M. Burcin, C. D. Allis, J. Zhou, C. A. Mizzen, N. J. McKenna, S. A. Onate, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1997. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 389:194-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torchia, J., D. W. Rose, J. Inostroza, Y. Kamei, S. Westin, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1997. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature 387:677-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tremblay, A., G. B. Tremblay, F. Labrie, and V. Giguère. 1999. Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor beta through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Mol. Cell 3:513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsai, M. J., and B. W. O'Malley. 1994. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:451-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tyler, J. K., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1999. The “dark side” of chromatin remodeling: repressive effects on transcription. Cell 99:443-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Umesono, K., K. K. Murakami, C. C. Thompson, and R. M. Evans. 1991. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell 65:1255-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, J. C., J. M. Stafford, and D. K. Granner. 1998. SRC-1 and GRIP1 coactivate transcription with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30847-30850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weigel, N. L., W. Bai, Y. Zhang, C. A. Beck, D. P. Edwards, and A. Poletti. 1995. Phosphorylation and progesterone receptor function. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53:509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weigel, N. L., and Y. Zhang. 1998. Ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. J. Mol. Med. 76:469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whitfield, G. K., P. W. Jurutka, C. A. Haussler, and M. R. Haussler. 1999. Steroid hormone receptors: evolution, ligands, and molecular basis of biologic function. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 32-33:110-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wong, C. W., and M. L. Privalsky. 1998. Transcriptional repression by the SMRT-mSin3 corepressor: multiple interactions, multiple mechanisms, and a potential role for TFIIB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5500-5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu, L., C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1999. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:140-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoh, S. M., and M. L. Privalsky. 2000. Resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH) syndrome reveals novel determinants regulating interaction of T3 receptor with corepressor. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 159:109-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshida, E., S. Aratani, H. Itou, M. Miyagishi, M. Takiguchi, T. Osumu, K. Murakami, and A. Fukamizu. 1997. Functional association between CBP and HNF4 in trans-activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 241:664-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zamir, I., J. Zhang, and M. A. Lazar. 1997. Stoichiometric and steric principles governing repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev. 11:835-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, J., X. Hu, and M. A. Lazar. 1999. A novel role for helix 12 of retinoid X receptor in regulating repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6448-6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]