Abstract

The actin-like MreB cytoskeletal protein and RNA polymerase (RNAP) have both been suggested to provide the force for chromosome segregation. Here, we identify MreB and RNAP as in vivo interaction partners. The interaction was confirmed using in vitro purified components. We also present convincing evidence that MreB and RNAP are both required for chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. MreB is required for origin and bulk DNA segregation, whereas RNAP is required for bulk DNA, terminus, and possibly also for origin segregation. Furthermore, flow cytometric analyses show that MreB depletion and inactivation of RNAP confer virtually identical and highly unusual chromosome segregation defects. Thus, our results raise the possibility that the MreB–RNAP interaction is functionally important for chromosome segregation.

Keywords: MreB, actin, RNA polymerase (RNAP), chromosome segregation, oriC, terC

In eukaryotic cells, the mitotic spindle apparatus segregates sister chromatids to daughter cells. In contrast, it is largely unknown how prokaryotic cells segregate their chromosomes. The seminal replicon model suggested that newly replicated sister chromosomes are attached to centrally located sites on the cell membrane that move toward opposite cell poles in parallel with cell elongation (Jacob et al. 1963). In this model, the process of chromosome segregation is essentially passive. In support of the replicon model, it was observed that nucleoids segregated slowly concomitantly with cell elongation. However, more recent experiments have shown that the movement of numerous chromosomal regions is rapid and independent of cell growth (Glaser et al. 1997; Gordon et al. 1997; Webb et al. 1997, 1998; Viollier et al. 2004). These observations are consistent with the existence of a mitotic-like apparatus that provides the force for active chromosome segregation (Sharpe and Errington 1999; Gerdes et al. 2004).

Several factors have been proposed to contribute to chromosome segregation. Most bacterial chromosomes (although not that of Escherichia coli) encode homologs of plasmid-borne partitioning loci (Gerdes et al. 2000; Yamaichi and Niki 2000). For example, soj and spo0J of Bacillus subtilis are homologs of the P1 parAB genes that actively segregate plasmid DNA (Lin and Grossman 1998; Li and Austin 2002). However, the soj spo0j locus is not required for rapid oriC movement during vegetative cell growth (Webb et al. 1998). Rather, soj spo0j seems to be required for proper organization and positioning of the oriC region during sporulation (Wu and Errington 2003) in parallel with RacA, which tethers the origin-proximal region to the cell poles (Ben-Yehuda et al. 2003, 2005). In E. coli, the migS site near oriC may function as a centromere-like site (Yamaichi and Niki 2004; Fekete and Chattoraj 2005).

Cytological evidence suggests that, in E. coli and B. subtilis, replication occurs from immobile replication factories located at mid-cell, raising the possibility that bidirectional extrusion of newly replicated chromosomal DNA from the stationary replisome could provide the force for oriC separation (Lemon and Grossman 1998, 2000; Koppes et al. 1999). Although appealing, this model raises the question whether the intrinsic flexibility of DNA would dissipate the pushing force exerted by the replication machinery. The persistence length of DNA in vivo is not known definitely, but estimates are in the range of 50 nm (Bellomy and Record 1990), which is substantially shorter than the distances traversed by separating oriC regions. Coupling of the newly replicated DNA to a large macromolecular structure could increase its rigidity, but so far there is no direct evidence for such a structure.

RNA polymerase (RNAP) has also been proposed as a driving force in chromosome segregation (Dworkin and Losick 2002). The force generated during transcription by a single stationary RNAP is ∼25 picoNewtons (pN) (Gelles and Landick 1998; Wang et al. 1998), making RNAP an even more powerful motor than either myosin or kinesin (Mehta et al. 1999). In in vitro assays, RNAP has been shown to be capable of moving DNA when immobilized on a solid surface (Gelles and Landick 1998). If the movement of RNAP in the cell is restricted, as has been proposed (Lewis et al. 2000; Cabrera and Jin 2003), then transcription could serve to translocate the chromosome. Consistent with this hypothesis, inhibition of transcription prevented normal separation of newly duplicated origin regions in B. subtilis (Dworkin and Losick 2002).

In eukaryotic cells, replicated chromosomes condense to form sister chromatid structures, which pair and align at mid-cell during the early stages of mitosis. Subsequently, the mitotic spindle apparatus, which consists of microtubule fibers anchored via the kinetochore to the centromere, pulls the sister chromatids toward opposite cell poles (Nasmyth 2002). Could cytoskeletal elements contribute to DNA segregation in bacteria? Indeed, the DNA segregation machinery encoded by E. coli plasmid R1 specifies a simple prokaryotic analog of the eukaryotic spindle apparatus. The plasmid-encoded ParM protein, an actin homolog, forms F-actin-like filaments that are responsible for the active separation of plasmids paired at mid-cell and subsequent movement of the plasmid copies to opposite cell poles (Jensen et al. 1998; Jensen and Gerdes 1999; Møller-Jensen et al. 2002, 2003). Furthermore, the chromosomally encoded actin homolog MreB has been shown to form dynamic actin-like cables that traverse the length of the cell (Jones et al. 2001; Kruse et al. 2003; Shih et al. 2003; Defeu Soufo and Graumann 2004; Figge et al. 2004; Gitai et al. 2004). In many rod-shaped bacteria, depletion of mreB leads to the formation of spherical cells (Wachi et al. 1987, 1989; Jones et al. 2001; Figge et al. 2004). It has been suggested that the bacterial actin-like cytoskeleton could serve as tracks for the cell-wall-synthesizing machinery, thereby controlling cell wall morphogenesis and, thus, cell shape (Daniel and Errington 2003; Figge et al. 2004). Moreover, in cells with impaired MreB function, the nucleoid and the origin and terminus regions of replication were found to localize at abnormal positions, suggesting that the MreB cytoskeleton, in addition to its role in cell shape determination, could provide the force for chromosome segregation (Kruse et al. 2003; Defeu Soufo and Graumann 2004; Gitai et al. 2004). Recent work in Caulobacter crescentus provided convincing evidence that MreB plays an important role in chromosome segregation (Gitai et al. 2005).

Here, we present evidence that inactivation of MreB inhibits chromosome segregation in E. coli. Coimmunoprecipitation combined with mass spectrometry identified RNAP as an MreB interaction partner. Inactivation of RNAP by rifampicin or by temperature-sensitive alleles in rpoC or rpoD (that encode the β′ and σ subunits of RNAP, respectively) also inhibited chromosome segregation. The findings presented here show that MreB is required for origin and bulk DNA segregation, whereas RNAP is required for bulk DNA and terminus segregation. The striking similarity of the chromosome distribution patterns of MreB-depleted cells and of cells with an inactivated RNAP raises the possibility that the interaction between MreB and RNAP plays an important role in chromosome segregation.

Results

A22 inhibits the function of MreB in E. coli

A22 [S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)isothiourea] is a new antibacterial compound that induces a round cell morphology and anucleate (i.e., chromosome-less) cells in E. coli and C. crescentus (Iwai et al. 2002; Gitai et al. 2005). In the latter organism, single amino acid changes in MreB conferred resistance to A22 and simultaneously prevented the formation of the round cell morphology, thus establishing that MreB is the cellular target of A22. By the construction and mapping of a mutation that confers A22 resistance in E. coli, we found that MreB is also the target of A22 in E. coli (described in Supplemental Material). Thus, a single point mutation in mreB (denoted mreB221) resulted in substitution of Asn21 to Asp of the MreB protein. Cells carrying the mreB221 mutation exhibited a normal cell morphology and chromosome segregation pattern (data not shown), indicating that the mutant MreB221 protein retains the roles of wild-type MreB in these cellular processes (see also below).

A22 blocks segregation of oriC and prevents nucleoid separation

We investigated the effect of A22, and thus of MreB, on chromosome segregation in E. coli. To this end, the GFP-ParB/parS system (Kruse et al. 2003) was used to tag the origin of replication (oriC). The technique exploits the fact that multiple GFP-ParB fusion proteins expressed from a coresident plasmid (pTK536) bind to the parS site and spread outward to cover adjacent sequences, causing the DNA region harboring parS to form a bright fluorescent signal.

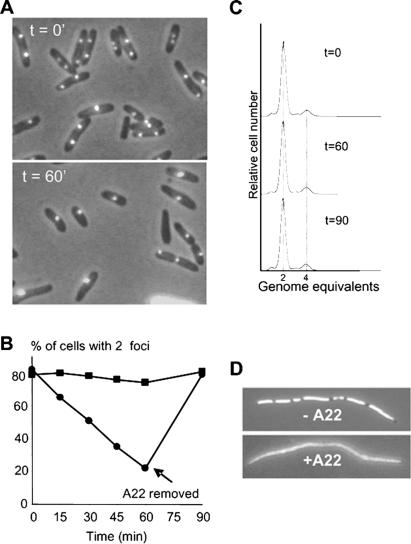

Wild-type cells and cells carrying an A22-insensitive allele of mreB were tagged with parS at oriC and grown in minimal medium with a doubling time of 90 min. In Figure 1A, origin localization was visualized in wild-type cells before addition of A22 (t = 0). Under these growth conditions, 82% of the cells contained two distinct origin foci. After exposure to A22 for 60 min, only 22% of the cells contained two origin foci (Fig. 1A,B). Importantly, after treatment of the cells for 60 min, the cells remained rod-shaped, suggesting that the effect observed on chromosome segregation was a direct effect of impaired MreB function rather than a secondary effect caused by a change in cell morphology. The rate of cell division was not seriously affected by A22 treatment for 60 min (data not shown). The effect of A22 on oriC segregation was reversible, as a shift to a medium without A22 restored the number of cells with two origin foci to 79% within 30 min (Fig. 1B). As a further control, cells carrying the mreB221-insensitive allele were also subjected to A22. In this strain, ∼80% of the cells contained two distinct oriC foci throughout the course of the experiment, confirming that the effect of A22 on chromosome segregation was caused by a direct inhibition of MreB function (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A22 inhibits chromosome segregation in E. coli. oriC was visualized by GFP-ParB nucleation on parS sites inserted in bglF (near oriC). The strains contain plasmid pTK536 that expresses the GFP-ParB fusion protein. Cells were grown at 30°C in AB minimal medium with 0.2% glycerol. (A) oriC localization in exponentially growing WA220 bglF::parS/pTK536 (wt; A22-sensitive) cells (top panel) or after treatment with 10 μg/mL A22 for 60 min (lower panel). (B) Frequency of cells containing two oriC foci in exponentially growing cells of WA220 bglF::parS/pTK536 (wt; filled circles) or WA221 bglF::parS/pTK536 (A22-resistant; filled squares) in medium containing 10 μg/mL A22. The arrow at 60 min indicates that the cells were shifted to medium without A22. oriC foci were counted in a minimum of 300 cells for every time point. (C) Origin counting by flow cytometry. Shown are flow cytometric histograms of E. coli strain WA220 bglF::parS/pTK536 grown exponentially without A22 (t = 0) or cultures treated with A22 for 60 min (t = 60) and cultures shifted to media without A22 for an additional 30 min (t = 90) after 4 h of treatment with rifampicin, which inhibits new rounds of replication but allows ongoing rounds to finish. Thus the genome equivalents counted reflect the number of origins present at the time of addition of the drug. (D) Effect of A22 on nucleoid morphology. Wild-type cells of strain MC1000 were grown in LB medium at 30°C in the presence of cephalexin for two doubling times (60 min) then with A22 (10 μg/mL) for another 40 min and stained with DAPI. (E) TK908 [MC1000 parS-oriC dnaA(ts)]/pTK536 cells were grown in AB minimal medium at 30°C and shifted to 39°C for 2 h to synchronize the cells with respect to replication initiation. Subsequently, the cells were moved back to 30°C for 20 min to allow reinitiation. At this point, the culture was divided into three separate portions. To one culture (squares), water was added (control); to the second (triangles), A22 (10 μg/mL) was added; and to the third (diamonds), rifampicin (100 μg/mL) was added. The three cultures were shifted back to 39°C for an additional 40 min to allow origin movement and to prevent further rounds of replication. Origin foci were counted in at least 300 cells per data point. Samples were withdrawn for analysis by flow cytometry in parallel as described in the text.

In principle, the observed inhibition of oriC segregation could be due to an effect of A22 on replication initiation. Therefore, samples for investigation of origin number by flow cytometry were withdrawn in parallel with those taken for visual inspection of origin localization. Untreated cultures contained predominantly two chromosome equivalents (Fig. 1C, t = 0). Cells treated with A22 for 60 min (t = 60) and cells shifted back to medium without A22 for an additional 30 min (t = 90) exhibited DNA distribution patterns that were virtually identical to that of untreated cells (Fig. 1C). These results show that A22 does not block initiation or elongation of DNA replication. Thus, cells treated with A22 must contain two copies of oriC that have not separated, indicating that MreB is required for segregation of the oriC region of E. coli.

To examine oriC movement in cells with duplicated origins more directly, we used a strain carrying a temperature-sensitive DnaA protein (TK908) also carrying parS at oriC. At nonpermissive temperature, this strain finishes replication of its chromosome while reinitiation at oriC is inhibited, thus providing a means for synchronizing cells with respect to chromosome replication. When grown at the permissive temperature (30°C), replication initiation was unaffected and ∼70% of the cells contained two origin foci (Fig. 1E). After 2 h at 39°C, only 8% of the cells contained two origin foci. Consistently, flow cytometry showed that the large majority of the cells contained one fully replicated chromosome (data not shown). Subsequently, the cells were moved back to permissive temperature for 20 min, a time period sufficient to allow reinitiation of replication as also measured by flow cytometry (data not shown). At this point, the cell culture was divided into two, one of which received A22. Subsequently, the cultures were placed at 39°C for an additional 40 min, after which samples were withdrawn for microscopic inspection. In the control sample without A22, 77% of the cells contained two origin foci, whereas in cells treated with A22, only 37% contained two origin foci. This result supports the hypothesis that A22 inhibits oriC segregation.

We also investigated the effect of A22 on bulk DNA segregation. When the cells were treated with cephalexin for two generations, cell division but not chromosome segregation was inhibited, resulting in long cell filaments with clearly separated nucleoids (Fig. 1D, upper panel). In contrast, when the cell filaments were treated with A22 for an additional 40 min, the nucleoids were seen as large confluent bodies (Fig. 1D, lower panel). Thus, A22 also inhibits bulk DNA segregation. In general, cephalexin-treated filamentous cells had clearly separated and regularly spaced nucleoids, indicating that cephalexin treatment itself did not perturb ordered DNA segregation.

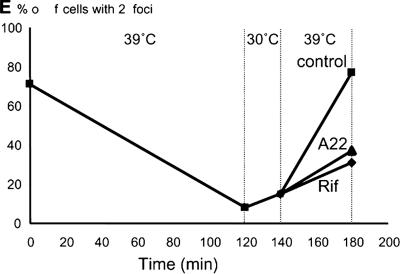

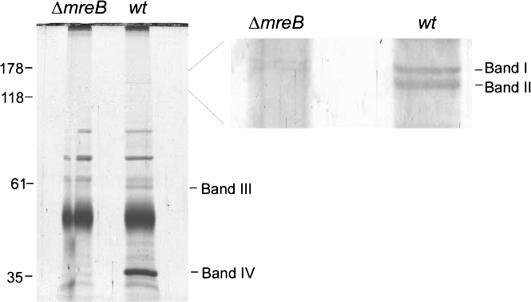

RNAP coimmunoprecipitates with MreB

We used a coimmunoprecipitation assay to identify potential MreB-interacting proteins. Cultures of exponentially growing ΔmreB and wild-type E. coli cells were lysed and their cell extracts immunoprecipitated with affinity-purified anti-MreB antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were divided into a small (10 μL) and a large (390 μL) portion. The small portions were used for immunoblotting as described below. The large portions were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel (SDA-PAGE), and the two gel lanes were visualized by colloidal Blue staining. The wild-type precipitate revealed four gel bands that were absent from the ΔmreB sample (Fig. 2). These bands were excised from the gel, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (see Materials and Methods for details). Surprisingly, the mass spectrometric analysis showed that the gel bands I and II contained a mixture of RNAP β and RNAP β′ chains. The unambiguous identification of the β subunit was based on 41 unique tryptic peptides from the upper band and 54 from the lower band. One of the peptides and its tandem mass spectrum are shown in Supplementary Figure S1A. For the β′ chain, 34 peptides were identified from the upper band, while 11 peptides were found from the lower one. The tandem mass spectrum for one of the doubly charged peptides is presented in Supplementary Figure S1B. Gel bands III and IV were identified as the chaperonin protein GroEL and MreB, respectively (data not shown). In E. coli, the RNAP core enzyme consists of the α, β, and β′ subunits (α2, β, and β′). The α subunit was not detected in the wild-type gel lane in Figure 2. However, the molecular masses of MreB (36.8 kDa) and the RNAP α subunit (36.4 kDa) are almost identical, and they are expected to migrate with similar mobilities under standard SDS-PAGE conditions. It is therefore likely that the presence of the α subunit in the immunoprecipitate prepared from wild-type cells is masked by the large abundance of MreB.

Figure 2.

Detection of proteins that coimmunoprecipitate with MreB. Cultures of exponentially growing MC1000 (wild type) and MC1000ΔmreB cells were lysed, and cleared lysates were incubated with affinity-purified anti-MreB antibodies coupled to Protein A agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by colloidal Blue staining. Four gel bands are present in the wild-type sample and absent from the control ΔmreB precipitate. These four gel bands were excised and processed for subsequent mass spectrometric analysis. The left panel shows the entire gel, whereas the right panel shows a magnification of the region surrounding bands 1 and 2.

To substantiate the observed in vivo interaction between MreB and RNAP, the small portions of the ΔmreB and wild-type immunoprecipitates mentioned above were subjected to Western blotting using monoclonal antibodies raised against the α, β, or β′ subunits of RNAP (Fig. 3A). In the lane (T) containing a total cell lysate from wild-type cells, all three subunits were detected, as expected. In the immunoprecipitate prepared from ΔmreB cells, none of the three subunits could be detected, whereas all three subunits were present in the immunoprecipitate from wild-type cells. As a further control, a wild-type culture of exponentially growing cells was lysed and the cell extracts immunoprecipitated with monoclonal antibodies against the β subunit of RNAP. The presence of MreB in this sample was subsequently investigated by Western blotting using anti-MreB antibodies. As is evident from Figure 3B, MreB was readily detected. Thus, MreB and RNAP interact in exponentially growing E. coli cells.

Figure 3.

MreB and RNAP interact in vivo and in vitro. (A) Lysates of exponentially growing MC1000 (wild type) and MC1000 ΔmreB cells were cleared and incubated with affinity-purified anti-MreB antibodies coupled to Protein A agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting using monoclonal antibodies against the α, β, or β′ subunits of RNAP. The lane marked T contains a total cell lysate prepared from MC1000. (B) Lysates of exponentially growing MC1000 (wild type) cells were cleared and incubated with monoclonal antibodies against the β subunit of RNAP. The immunoprecipitated sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting using anti-MreB antibodies (wt IP). The lanes marked ΔmreB and T contain total cell lysates prepared from MC1000 ΔmreB and MC1000 cells, respectively. (C) RNAP at a concentration of 0.25 μM was cross-linked by BS3 treatment to increasing concentrations of His-tagged MreB (lanes 4–7), His-tagged ParR (lane 8), or His-tagged ParB (lane 9). His-tagged MreB was used at a 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM concentration. His-tagged ParR or ParB was used at a 10 μM concentration. In lanes 2 and 3 there was no MreB or RNAP in the reaction mixtures, respectively. Protein complexes were sedimented by addition of Talon cobalt resin to the reaction mixtures, separated by SDS-PAGE, and subsequently subjected to immunobloting using monoclonal antibodies against the α, β, or β′ subunits of RNAP as indicated. Lane 1 shows 750 ng of purified RNAP.

In vitro interaction of MreB and RNAP

To substantiate the above findings, the interaction between His-tagged MreB and RNAP was analyzed in an in vitro experiment in which BS3 was used as a cross-linking reagent. Chemical cross-linking with BS3 is a well-established method allowing the identification of protein–protein interactions (Glover et al. 2001). BS3 is a homo-bifunctional cross-linker with a chain length of 11.4 Å and has reactivity toward amino groups. After cross-linking, protein complexes were sedimented by addition of Talon cobalt resin and subjected to Western blotting using monoclonal antibodies raised against the α, β, or β′ subunits of RNAP. A range of His-tagged MreB concentrations was used to sediment RNAP, and all three RNAP subunits could be detected in these reactions (Fig. 3C, lanes 4–7). In cross-linking reactions with no His-tagged MreB or RNAP, none of the RNAP subunits were detected (Fig. 3C, lanes 2,3). In control reactions with His-tagged MreB substituted with His-tagged ParR of Plasmid R1 or His-tagged ParB of P1, no RNAP subunits were detected either, thus verifying the specificity of the cross-linking assay (Fig. 3C, lanes 8,9). Hence, MreB and RNAP interact also in vitro. The increased mobilities of β and β′ in Figure 3C probably reflect intersubunit cross-linking.

Inhibition of RNAP prevents nucleoid separation

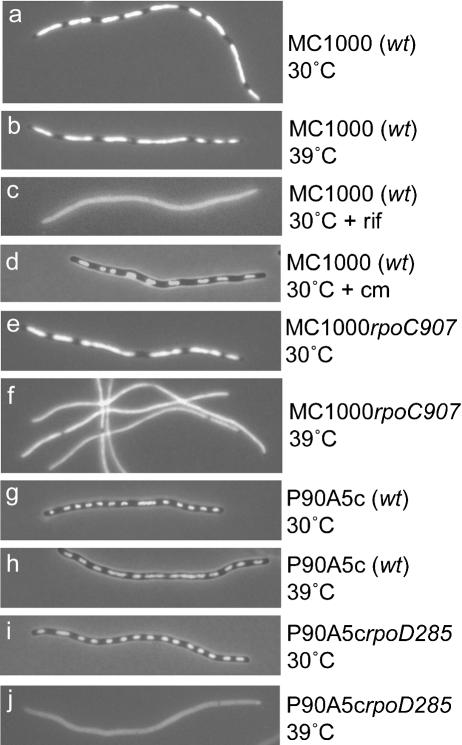

Since RNAP and MreB interact and MreB is required for chromosome segregation, we also investigated if RNAP plays a role in chromosome segregation. First, we examined the overall nucleoid pattern in cells in which RNAP had been inhibited by the addition of rifampicin, which blocks transcription initiation in bacteria. Cells were grown in LB medium and treated with cephalexin and DNA stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize the chromosome localization pattern in elongated cells. Cephalexin blocks cell division but allows cell elongation and chromosome segregation. As expected, wild-type cells of strain MC1000 grown at 30°C or 39°C had regularly spaced and clearly separated nucleoids (Fig. 4a,b). However, wild-type cells treated with rifampicin for 30 min exhibited a total loss of nucleoid separation (Fig. 4c). In contrast, addition of chloramphenicol led to condensed and clearly separated nucleoids (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of RNAP prevents nucleoid separation. Cells were grown exponentially for eight generations at 30°Cin LB medium and then in the presence of cephalexin (10 μg/mL) for three generations. In strains involving a temperature-sensitive RNAP, the cultures were shifted to semipermissive temperature (39°C) simultaneous with the addition of cephalexin. Nucleoid morphology was visualized by DAPI staining. (rif) Cells were treated with rifampicin (100 μg/mL) for 30 min after cephalexin treatment for three generations; (cm) cells were treated with chloramphenicol (100 μg/mL) for 10 min after cephalexin treatment. The strains used are listed in Table 1.

To substantiate that the effect seen with rifampicin reflected a general phenomenon and was not a result of a specific drug, we also investigated the nucleoid morphology in cells carrying different temperature-sensitive alleles in rpoC (encoding the β′ subunit) and rpoD (encoding the σ subunit). Cells carrying the rpoC907 mutation grew normally at permissive temperature (30°C). In contrast, at semipermissive temperature (39°C), transcription was reduced by ∼50% (Petersen and Hansen 1991). At 30°C, cells of MC1000 rpoC907 had clearly separated nucleoids, whereas growth at 39°C clearly prevented nucleoid segregation (Fig. 4e,f). Similarly, cells of strain P90A5c carrying a temperature-sensitive allele in rpoD exhibited coalesced nucleoids at semipermissive temperature but not at permissive temperature (Fig. 4i,j), whereas wild-type cells exhibited no such effect at either temperature (Fig. 4g,h). Cells carrying two other rpoCts alleles (rpoC56 and rpoC397) (see Table 1) grew slowly and exhibited confluent nucleoids even at permissive temperature (data not shown). These results show that inhibition of RNAP prevents nucleoid separation in E. coli.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strains and plasmids | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MC1000 | araD139Δ(ara, leu)7697 ΔlacX74 galU galK atrA | Casadaban et al. 1980 |

| SPE83 | MC1000::rpoC907(ts) | Petersen and Hansen 1991 |

| P90A5c | argG lac thi | Isaksson et al. 1977 |

| P90A5c285 | argG lac thi rpoD285(ts) | Isaksson et al. 1977 |

| P90A5c397 | argG lac thi rpoC397(ts) | Isaksson et al 1977 |

| XH56 | F-his thi metB bfe purD argH-2 strA lac rpoC56(ts) | Kirschbaum et al. 1975 |

| ALO454 | C600 Δlac tna::Tn10 dnaA48(ts) | Løbner-Olesen et al. 1992 |

| WA220 | W3110 zhc-12::Tn10 mreB+ (A22 sensitive) | This work |

| WA221 | W3110 zhc-12::Tn10 mreB221 (A22 resistant) | This work |

| TK220 | WA220 bflF::parS | This work |

| TK221 | WA221 bglF::parS | This work |

| TK907ori | SPE83 bglF::parS | This work |

| TK907ter | SPE83 relBE::parS | This work |

| TK908 | MC1000 bglF::parS dnaA48(ts) | This work |

| pTK536 | pBAD::SD-parM::gfp::parB | Kruse et al. 2003 |

| pTK500 | pA1/O4/O3::his8::mreB | Kruse et al. 2003 |

Origin and terminus localization in RNAP-deficient cells

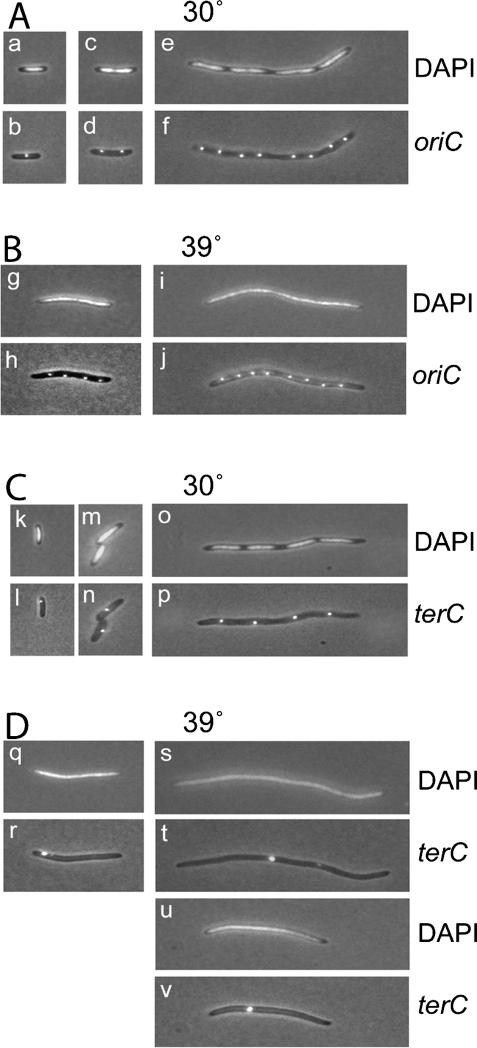

Using the GFP-ParB/parS system described above, we performed a double labeling experiment on rpoC907/ parS-oriC or rpoC907/parS-terC cells in which both the nucleoid and the oriC/terC-proximal regions were visualized. At the permissive temperature, the nucleoids were visible as distinct entities both in cells grown with and without cephalexin (e.g., Fig. 5A [panels c,e], C [panel o]). In rpoC907/parS-oriC cells grown at the permissive temperature, foci localized at mid-cell or at the quarter-cell positions consistent with previous observations in wild-type cells (Fig. 5A, panels b,d; Niki et al. 2000; Kruse et al. 2003). When these cells were treated with cephalexin, the origin-proximal parS sites distributed as multiple, equally spaced foci throughout the long axis of the elongated cells (Fig. 5A, panel f). Surprisingly, the origin localization pattern did not change when the rpoC907/parS-oriC cells were shifted to the semipermissive temperature even though the nucleoid morphologies were severely impaired under these conditions (Fig. 5B, panels g–j). When shifted to semipermissive temperature, rpoC907 cells tended to become somewhat elongated. These cells often contained three or four foci that were, however, also distributed in a regular fashion (Fig. 5B, panel h).

Figure 5.

oriC and terC localization after inactivation of RNAP. Simultaneous nucleoid and oriC or nucleoid and terC labeling. Cells of MC1000 rpoC907 oriC::parS at 30°C (A), MC1000 rpoC907 oriC::parS at 39°C (B), MC1000 rpoC907 terC::parS at 30°C (C), and MC1000 rpoC907 terC::parS at 30°C (D) were grown in AB minimal medium at 30°C for eight generations and then shifted to 39°C for two generations. Cells in the right panel were treated with cephalexin for two mass doublings; the drug was added simultaneously with the shift to nonpermissive temperature. oriC and terC were visualized by GFP-ParB (encoded by pTK536 also present in the cells) binding to parS sites inserted in bglF (near oriC) or in relBE (near terC). DNA was visualized by DAPI staining.

In rpoC907/parS-terC cells grown at the permissive temperature, terC localized near the pole in newborn cells or at mid-cell in predivisional cells (Fig. 5C, panels l,n), and cephalexin-treated cells had multiple foci that were distributed regularly along the long cell axis (Fig. 5C, panel p). Again, the patterns of terC localization were similar to those previously observed in wild-type cells (Niki et al. 2000; Kruse et al. 2003). In contrast, when the rpoC907/parS-terC cells were shifted to semipermissive temperature, the terminus-proximal parS sites were found to be severely dislocated. Frequently, terminus foci were observed to locate at the cell poles even in longer cells, suggesting that the normal pole to mid-cell transition of terC was impaired (Fig. 5D, panel r). In the majority of cells treated with cephalexin, the terC region appeared as a single fluorescent focus at or near the middle of a cell filament (Fig. 5D, panels t,v). Furthermore, the terC-proximal foci emitted a brighter fluorescent signal in these cells as compared with cells grown at the permissive temperature, suggesting that the foci represent multiple termini regions that do not separate. Thus, partial inhibition of RNAP affects the segregation of bulk DNA, that is, the nucleoid and the terC region but apparently not the oriC region.

When the rpoC907 strain was grown at the semipermissive temperature (39°C), RNAP was only partially inactivated. Therefore, the apparent normal segregation phenotype of the oriC region (Fig. 5A) under these conditions could be due to residual RNAP activity. Moving cells carrying the rpoC907 allele to 42°C completely inactivates their transcription. However, at 42°C we could not detect the oriC region in these cells, probably because the GFP-ParB reporter protein becomes nonfunctional. As in the case of A22, we therefore used the dnaA(ts) strain to investigate the effect of rifampicin on the oriC segregation pattern in cells with newly duplicated origin regions (Fig. 1E). As seen, addition of rifampicin inhibited origin separation significantly. This result raises the possibility that RNAP is also involved in segregation of the origin region although we do not exclude that the effect of rifampicin could be indirect.

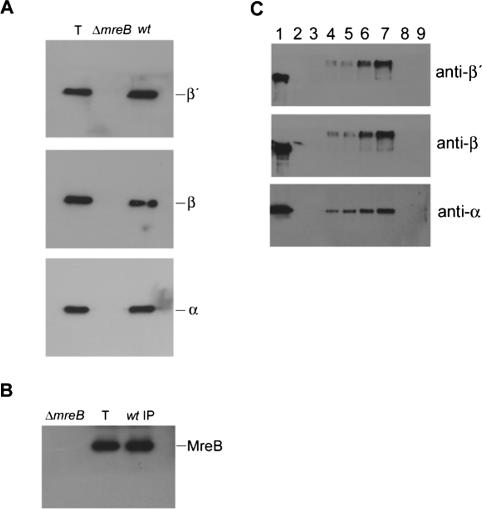

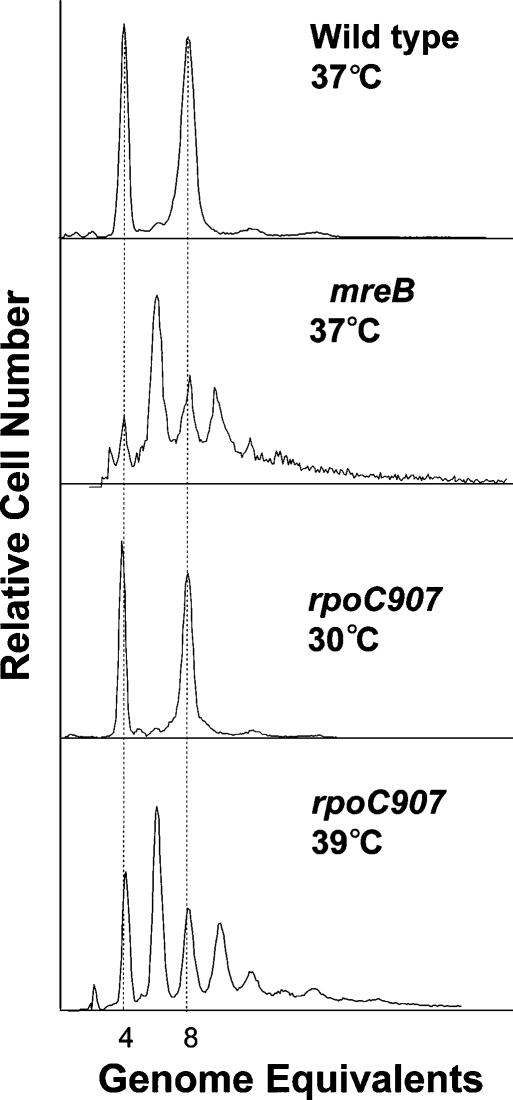

MreB- and RNAP-deficient cells both contain even numbers of replication origins

Numbers of replication origins of wild-type, ΔmreB, and rpoC907 cells were determined by flow cytometry. We exploited the fact that rifampicin stops new rounds of replication initiations at oriC but allows ongoing replication forks to finish. When wild-type cells are treated with rifampicin, they finally end up with 2N fully replicated chromosomes (N = 1, 2, 3, 4) because they segregate their chromosomes evenly (Skarstad et al. 1986). Consistently, rapidly growing wild-type cells predominantly had four or eight chromosomes (Fig. 6, top panel). In contrast, ΔmreB cells contained two, four, six, eight, 10, 12, or even 14 chromosomes (Fig. 6, second panel). When grown at the permissive temperature, rpoC907 cells, like wild-type cells, contained four or eight chromosomes (Fig. 6, third panel). On the other hand, rpoC cells incubated at the semipermissive temperature had a DNA distribution pattern very similar to that of mreB mutant cells, that is, they contained two, four, six, eight, 10, 12, or 14 chromosomes (Fig. 6, bottom panel), as observed previously (Boye et al. 1988).

Figure 6.

Number of replication origins in single cells counted by flow cytometry. Shown are flow cytometric histograms of E. coli strains MC1000 (wild type), MC1000 ΔmreB, and MC1000 rpoC907 obtained after 4 h of treatment with rifampicin. The cells were grown in LB medium. The wild-type and MC1000 ΔmreB strains were grown at 37°C, whereas MC1000 rpoC907 was grown at 30°C and 39°C.

Discussion

Eukaryotic cells use actin in a vast variety of cellular processes, including cell motility, shape determination, intracellular transport, transcription, and chromosome congression in oocytes (Pollard 2003; Pollard and Borisy 2003; Lenart et al. 2005; Visa 2005). In rod-shaped bacteria, the actin-like MreB protein forms cytoskeletal filaments located beneath the cell surface (Jones et al. 2001; Kruse et al. 2003; Figge et al. 2004). The filaments are responsible for cell morphology (Jones et al. 2001; Figge et al. 2004; Gitai et al. 2005; Kruse et al. 2005) and global cell polarity (Gitai et al. 2004; Nilsen et al. 2005). Indirect evidence obtained with E. coli and B. subtilis suggested that MreB is also involved in chromosome segregation (Defeu Soufo and Graumann 2003; Kruse et al. 2003). However, in another study, mreB could be deleted without an apparent effect on chromosome segregation (Formstone and Errington 2005). This apparent difference is not yet understood, but B. subtilis encodes two additional actin homologs (Mbl and MreBH) that may participate in chromosome segregation. Recent evidence obtained with C. crescentus pointed to a direct role for MreB in chromosome segregation (Gitai et al. 2005). In C. crescentus, A22 disrupted the regular GFP-MreB filament pattern and simultaneously blocked segregation of the origin proximal region, implying that MreB filament formation is required for origin movement. Consistently, anti-MreB antibodies specifically precipitated DNA derived from the origin region. In contrast, A22 did not inhibit segregation of bulk DNA once the origin region had been allowed to move. These results suggest that the C. crescentus chromosome is segregated by two separate machineries, one that depends on MreB and one that does not (Gitai et al. 2005).

We show here that MreB is also the target of A22 in E. coli. As in C. crescentus, addition of A22 rapidly and reversibly blocked separation of newly replicated oriC regions (Fig. 1). Segregation of bulk DNA was also affected by A22. Thus MreB functions directly in chromosome segregation in these two distantly related γ- and α-proteobacteria. Our observations prompted a search for MreB interaction partners. Using a coimmunoprecipitation assay followed by mass spectrometric analysis, we identified RNAP and GroEL as interaction partners with MreB in E. coli (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). The interaction between RNAP and MreB was confirmed in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 3). While this work was ongoing, two large-scale analyses of interacting proteins in E. coli proposed that RNAP and GroEL both interact with MreB in vivo, thus supporting the interactions described here (Butland et al. 2005; Kerner et al. 2005). The most abundant RNAP σ factor, σ70, that is responsible for initiation at most E. coli promoters during exponential growth did not appear to coimmunoprecipitate with MreB. After RNAP has transcribed ∼10 base pairs (bp), the σ70 subunit is released from the holoenzyme. Therefore the apparent absence of σ70 from the immunoprecipitation reactions shown in Figure 2 may reflect that MreB preferentially interacts with actively transcribing RNAP. We showed previously that MreB interacts with the MreC cell shape determinant (Kruse et al. 2005). This interaction was not detected here. MreC is a transmembrane protein, and the lysis conditions used in the immunoprecipitation assay may fail to release membrane proteins into solution; consequently, these proteins could be lost during the clearing step. Alternatively, MreC may be produced in too low amounts to be detected by this immunoprecipitation method.

Inactivation of RNAP, either by the addition of rifampicin or by using temperature-sensitive RNAP alleles, consistently led to decondensation of the bacterial nucleoid (Fig. 4). Simultaneously, the terC region exhibited a highly aberrant localization pattern, often with multiple coalesced termini located at the middle of long cell filaments (Fig. 5). These results indicate that RNAP is involved in chromosome segregation. This conclusion was supported by the previous observation that sublethal amounts of rifampicin leads to the formation of anucleate cells (Wachi et al. 1999).

Previously, we showed that ectopic expression of transdominant alleles of MreB also decondensed the E. coli nucleoid (Kruse et al. 2003). In such cells, the oriC and terC regions localized aberrantly, and the terC patterns were very similar to those shown in Figure 5 (Kruse et al. 2003). Thus, interference with RNAP or with MreB confers similar gross changes of bulk DNA and terC. In contrast, the origin-proximal region exhibited a regular pattern of distribution in cells with a partially inactivated RNAP (Fig. 5). Thus, cells with a decondensed nucleoid and highly distorted terC localization pattern had a regular oriC distribution indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells. However, addition of rifampicin to cells with newly replicated origins significantly reduced origin separation (Fig. 1E). It is thus possible that segregation of oriC also depends on RNAP, although we do not exclude the possibility that the effect of rifampicin on oriC separation could be indirect. In conclusion, our results show that segregation of bulk DNA and the terminus region depends on both MreB and RNAP, whereas origin segregation depends on MreB and perhaps RNAP.

Our observations raise the obvious question of the function of the MreB–RNAP interaction. RNAP has been suggested to provide the driving force for chromosome segregation in bacteria (Dworkin and Losick 2002). If RNAP is stationary, or even partially immobilized, then transcription per se would cause movement of the DNA template within the cell (Cook 1999). Furthermore, the involvement of RNAP in DNA movement is not unprecedented. During infection of E. coli by bacteriophage T7, the E. coli RNAP propels T7 DNA from the phage into the host cell (Zavriev and Shemyakin 1982). In eukaryotic cells, the rapid movement of interphase chromatin was suggested to reflect RNAP activity itself, and the movement of a particular chromosomal locus within the nucleoid has been correlated with its transcriptional activity (Buchenau et al. 1997). Therefore, one possibility is that an interaction between the MreB cytoskeleton and RNAP could serve to immobilize the transcription machinery in such a way that the motor power of the polymerase would drive chromosome segregation.

The observation that mreB and rpoC mutant cells share strikingly similar and unusual chromosome distribution patterns (Fig. 6) is consistent with the proposal that MreB and RNAP function together in chromosome segregation. The patterns suggest that the chromosomes segregate randomly in both cell types. It should be noted that the chromosome distribution pattern of the rpoC907 mutant cells (Fig. 6, bottom panel) is not a mere consequence of the ∼50% larger average size of these cells since minD mutant cells have a similar size distribution and exhibit a normal chromosome distribution pattern (Kruse et al. 2003).

The MreB proteins assemble into helical cables, locating just under the cytosolic membrane (Jones et al. 2001; Shih et al. 2003). Time-lapse microscopy analysis revealed that the MreB cables continuously move along helical tracks underneath the cell membrane (Defeu Soufo and Graumann 2004). Specifically, the MreB filaments moved away from mid-cell toward opposite cell poles. This observation together with the finding that, in cells with impaired MreB function, the nucleoid and the origin and terminus regions localize at abnormal positions, makes the MreB cytoskeleton another possible candidate for the generation of the force needed for chromosome segregation (Defeu Soufo and Graumann 2003; Kruse et al. 2003; Gitai et al. 2005). Therefore, an alternative interpretation of the data presented here is that chromosomal DNA bound by RNAP is actively driven toward opposite cell poles by the interaction with the dynamic MreB cables.

The presence of actin in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells is well documented (Pederson and Aebi 2002; Bettinger et al. 2004), and several recent papers have established that there is a direct physical interaction between nuclear actin and all three RNAPs (for review, see Visa 2005). Apparently, binding of nuclear actin to the transcription machinery stimulates the initiation and elongation of transcription by RNAPs. In E. coli, MreB affects the transcription rates of ftsI (encoding PBP3) and ponB (encoding PBP1B) (Wachi and Matsuhashi 1989). It will be interesting to learn if MreB influences the global transcription pattern of E. coli.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. MC1000 ΔmreB contains an in-frame deletion in which all but the 3′ and 5′ 36 bp were deleted (Kruse et al. 2003). The mreB221 mutation is a substitution of the 21st Asn to Asp in the MreB protein. The bglF::parS and relBE::parS fusions were transduced to the strains indicated from the MC1000 bglF::parS and MC1000 relBE::parS strains (Kruse et al. 2003), respectively. The bglF gene is located 22 kb from oriC, while relBE is located 55 kb from the dif recombination site in the terminus region. The dnaA48(ts) mutation of strain ALO454 was P1 transduced into MC1000 bglF::parS/pTK536, resulting in strain TK908. Cells were grown in LB medium or in AB glycerol supplemented with casamino acids as indicated. A22 was used at a concentration of 10 μg/mL.

Fluorescence microscopy and image acquisition

To express GFP-ParB, cells containing pTK536 were grown in AB glycerol supplemented with casamino acids or in LB medium as indicated. Expression of the ParB-GFP fusion protein was induced by 0.2% arabinose. Induction for 60–120 min before microscopy yielded optimal results. Cells expressing ParB-GFP were immobilized on microscope slides using a thin film of agarose (Glaser et al. 1997). The cells were observed with a Leica DMRA fluorescence and phase-contrast microscope with a Leica PL APO 100×/1.40 objective. Pictures were obtained with a Leica DC500 color CCD camera and stored digitally using the Leica IM500 computer software.

In vitro interaction between MreB and RNAP

To overproduce His-MreB in E. coli, MC1000/pTK500 was grown to an OD450 of 0.6, and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM for a further 3 h. The protein was purified on a Talon cobalt resin as described by the manufacturer (Clontech). Purified RNAP was supplied from Epicentre. Purified and His-tagged ParR and ParB were a gift from Simon Ringgaard (Syddansk Universitet [University of Southern Denmark], Odense, Denmark). Increasing concentrations (0.03, 0.06, 0.12, or 0.24 μg/μL) of His-tagged MreB were mixed with 0.05 μg/μL RNAP holoenzyme in binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2) to a final volume of 30 μL and incubated at 25°C for 15 min. Then the cross-linking reagent BS3 (bis[sulfosuccinimido]suberate; Pierce) was added to a final concentration of 2 mM, and the reaction was incubated for a further 30 min at 25°C, after which the reaction was quenched for 15 min at 25°C by addition of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 30 mM. Subsequently, 30 μL of Talon cobalt resin was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated with continuous shaking for 2 h at 4°C. The protein–resin complex was washed four times in binding buffer, followed by a step in which proteins bound to the Talon resin were eluted by adding imidazole to a final concentration of 200 mM. The precipitated complexes were separated by 7% SDS-PAGE, and the gel was subjected to Western blotting using anti-α, anti-β, or anti-β′ monoclonal antibodies. As controls, we also tested the binding between RNAP and His-tagged ParR or His-tagged parB as described above. The His-tagged versions of ParR and ParB were used at a final concentration of 0.24 μg/μL.

Immunological methods

For immunoprecipitation, 50-mL cultures were grown at 37°C to an OD450 of 0.5, harvested, resuspended in 4 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet, and a cocktail of EDTA-free protease inhibitors; Roche). The cells were lysed by passage through a French pressure cell at 750 atm, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000g for 30 min at 4°C. Cleared cell lysates were incubated for 4 h at 4°C with affinity-purified anti-MreB polyclonal antibodies or anti-β monoclonal antibodies coupled to protein A agarose beads (Sigma). Precipitated immune complexes were washed four times with lysis buffer and then eluted with SDS-lysis buffer. The precipitated complexes were separated on a NuPAGE 4 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen), and the gel was stained with the colloidal Blue staining kit (Invitrogen) to visualize gel lanes, or the immune complexes were separated by standard SDS-PAGE and the relevant protein bands visualized by Western blotting as indicated. For Western blots, samples were loaded onto a 10% (MreB blots) or 8% (RNAP blots) SDA-PAGE, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to an Immobilon P membrane (Pharmacia) with a semidry blotting apparatus. Western blots were prepared by standard procedures. The membranes were probed with anti-MreB serum diluted 1: 10,000 or anti-α, anti-β, or anti-β′ monoclonal antibodies (Neoclone) diluted 1:5000 as indicated, followed by peroxidase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit Immunoglobulin G diluted 1:3000 or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G 1:1500 (DAKO). Detection was performed with Renaissance Plus chemiluminescence reagent (NEN). Affinity purification of anti-MreB antibodies was performed as described previously (Kruse et al. 2003).

Mass spectrometric analysis

Protein bands were excised and subjected to in-gel reduction, alkylation, and trypsin digestion as described previously (Blagoev et al. 2003). Subsequently, the samples were desalted and concentrated using STAGE tips (Rappsilber et al. 2003). The peptide mixtures were then analyzed with nanoscale liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and LC-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with a QSTAR-Pulsar quadrupole time-of-flight instrument (ABI-MDS-SCIEX) essentially as described previously (Blagoev et al. 2004). The peptides were chromatographically separated with a linear gradient elution from 95% buffer A (H2O/acetic acid, 100:0.5 vol/vol) to 50% buffer B (H2O/acetonitrile/acetic acid, 20:80:0.5 vol/vol) in 80 min. Protein identification was done with the Mascot software package (Matrix Science) using the NCBI nonredundant protein database.

Flow cytometry

For the determination of numbers of origins per cell by flow cytometry, cells were grown in LB medium or in AB glycerol supplemented with casamino acids as indicated. Prior to flow cytometry, cells were treated with 300 μg/mL of rifampicin (to stop further replication initiations) and 3.6 μg/mL of cephalexin (to stop further cell divisions). Flow cytometry was performed as described (Løbner-Olesen et al. 1989), using a Bryte instrument (Apogee Flow Systems).

Acknowledgments

We thank Rasmus Bugge Jensen and Jakob Møller-Jensen for critical comments to the manuscript. We also thank Gail Christie for the donation of bacterial strains. This work was supported by the Danish Biotechnology Instrument Centre (DABIC), The Danish Natural Research Council, The Carlsberg Foundation, The Danish National Research Foundation, and The Novo Nordic Foundation.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.366606.

References

- Bellomy G.R. and Record Jr., M.T. 1990. Stable DNA loops in vivo and in vitro: Roles in gene regulation at a distance and in biophysical characterization of DNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 39: 81–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehuda S., Rudner, D.Z., and Losick, R. 2003. RacA, a bacterial protein that anchors chromosomes to the cell poles. Science 299: 532–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehuda S., Fujita, M., Liu, X.S., Gorbatyuk, B., Skoko, D., Yan, J., Marko, J.F., Liu, J.S., Eichenberger, P., Rudner, D.Z., et al. 2005. Defining a centromere-like element in Bacillus subtilis by identifying the binding sites for the chromosome-anchoring protein RacA. Mol. Cell 17: 773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger B.T., Gilbert, D.M., and Amberg, D.C. 2004. Actin up in the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5: 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoev B., Kratchmarova, I., Ong, S.E., Nielsen, M., Foster, L.J., and Mann, M. 2003. A proteomics strategy to elucidate functional protein–protein interactions applied to EGF signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 21: 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoev B., Ong, S.E., Kratchmarova, I., and Mann, M. 2004. Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 1139–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boye E., Lobner-Olesen, A., and Skarstad, K. 1988. Timing of chromosomal replication in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 951: 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchenau P., Saumweber, H., and Arndt-Jovin, D.J. 1997. The dynamic nuclear redistribution of an hnRNP K-homologous protein during Drosophila embryo development and heat shock. Flexibility of transcription sites in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 137: 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butland G., Peregrin-Alvarez, J.M., Li, J., Yang, W., Yang, X., Canadien, V., Starostine, A., Richards, D., Beattie, B., Krogan, N., et al. 2005. Interaction network containing conserved and essential protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nature 433: 531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera J.E. and Jin, D.J. 2003. The distribution of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is dynamic and sensitive to environmental cues. Mol. Microbiol. 50: 1493–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadaban M.J., Chou, J., and Cohen, S.N. 1980. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active β-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J. Bacteriol. 143: 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P.R. 1999. The organization of replication and transcription. Science 284: 1790–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel R.A. and Errington, J. 2003. Control of cell morphogenesis in bacteria: Two distinct ways to make a rod-shaped cell. Cell 113: 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defeu Soufo H.J. and Graumann, P.L. 2003. Actin-like proteins MreB and Mbl from Bacillus subtilis are required for bipolar positioning of replication origins. Curr. Biol. 13: 1916–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2004. Dynamic movement of actin-like proteins within bacterial cells. EMBO Rep. 5: 789–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J. and Losick, R. 2002. Does RNA polymerase help drive chromosome segregation in bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 14089–14094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete R.A. and Chattoraj, D.K. 2005. A cis-acting sequence involved in chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge R.M., Divakaruni, A.V., and Gober, J.W. 2004. MreB, the cell shape-determining bacterial actin homologue, co-ordinates cell wall morphogenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 51: 1321–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formstone A. and Errington, J. 2005. A magnesium-dependent mreB null mutant: Implications for the role of mreB in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 1646–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles J. and Landick, R. 1998. RNA polymerase as a molecular motor. Cell 93: 13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K., Moller-Jensen, J., and Jensen, R.B. 2000. Plasmid and chromosome partitioning: Surprises from phylogeny. Mol. Microbiol. 37: 455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K., Moller-Jensen, J., Ebersbach, G., Kruse, T., and Nordström, K. 2004. Bacterial mitotic machineries. Cell 116: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitai Z., Dye, N., and Shapiro, L. 2004. An actin-like gene can determine cell polarity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 8643–8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitai Z., Dye, N.A., Reisenauer, A., Wachi, M., and Shapiro, L. 2005. MreB actin-mediated segregation of a specific region of a bacterial chromosome. Cell 120: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser P., Sharpe, M.E., Raether, B., Perego, M., Ohlsen, K., and Errington, J. 1997. Dynamic, mitotic-like behavior of a bacterial protein required for accurate chromosome partitioning. Genes & Dev. 11: 1160–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover B.P., Pritchard, A.E., and McHenry, C.S. 2001. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains: Domain III, shared by γ and τ, oligomerizes DnaX. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 35842–35846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G.S., Sitnikov, D., Webb, C.D., Teleman, A., Straight, A., Losick, R., Murray, A.W., and Wright, A. 1997. Chromosome and low copy plasmid segregation in E. coli: Visual evidence for distinct mechanisms. Cell 90: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson L.A., Skold, S.E., Skjoldebrand, J., and Takata, R. 1977. A procedure for isolation of spontaneous mutants with temperature sensitive of RNA and/or protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 156: 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai N., Nagai, K., and Wachi, M. 2002. Novel S-benzylisothiourea compound that induces spherical cells in Escherichia coli probably by acting on a rod-shape-determining protein(s) other than penicillin-binding protein 2. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66: 2658–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F., Brenner, S., and Cuzin, F. 1963. On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 23: 329–348. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R.B. and Gerdes, K. 1999. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: ParM partitioning protein of plasmid R1 co-localizes with its replicon during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 18: 4076–4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R.B., Lurz, R., and Gerdes, K. 1998. Mechanism of DNA segregation in prokaryotes: Replicon pairing by parC of plasmid R1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 8550–8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L.J., Carballido-Lopez, R., and Errington, J. 2001. Control of cell shape in bacteria: Helical, actin-like filaments in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104: 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner M.J., Naylor, D.J., Ishihama, Y., Maier, T., Chang, H.C., Stines, A.P., Georgopoulos, C., Frishman, D., Hayer-Hartl, M., Mann, M., et al. 2005. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell 122: 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum J.B., Claeys, I.V., Nasi, S., Molholt, B., and Miller, J.H. 1975. Temperature-sensitive RNA polymerase mutants with altered subunit synthesis and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 72: 2375–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppes L.J., Woldringh, C.L., and Nanninga, N. 1999. Escherichia coli contains a DNA replication compartment in the cell center. Biochimie 81: 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse T., Møller-Jensen, J., Løbner-Olesen, A., and Gerdes, K. 2003. Dysfunctional MreB inhibits chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 22: 5283–5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse T., Bork-Jensen, J., and Gerdes, K. 2005. The morphogenetic MreBCD proteins of Escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon K.P. and Grossman, A.D. 1998. Localization of bacterial DNA polymerase: Evidence for a factory model of replication. Science 282: 1516–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2000. Movement of replicating DNA through a stationary replisome. Mol. Cell 6: 1321–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenart P., Bacher, C.P., Daigle, N., Hand, A.R., Eils, R., Terasaki, M., and Ellenberg, J. 2005. A contractile nuclear actin network drives chromosome congression in oocytes. Nature 436: 812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P.J., Thaker, S.D., and Errington, J. 2000. Compartmentalization of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 19: 710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. and Austin, S. 2002. The P1 plasmid is segregated to daughter cells by a `capture and ejection' mechanism coordinated with Escherichia coli cell division. Mol. Microbiol. 46: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D.C. and Grossman, A.D. 1998. Identification and characterization of a bacterial chromosome partitioning site. Cell 92: 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Løbner-Olesen A., Skarstad, K., Hansen, F.G., von Meyenburg, K., and Boye E.A. 1989. The DnaA protein determines the initiation mass of Escherichia coli K-12. Cell 57: 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Løbner-Olesen A., Boye, E., and Marinus, M.G. 1992. Expression of the Escherichia coli dam gene. Mol. Microbiol. 6: 1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A.D., Rief, M., Spudich, J.A., Smith, D.A., and Simmons, R.M. 1999. Single-molecule biomechanics with optical methods. Science 283: 1689–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller-Jensen J., Jensen, R.B., Löwe, J., and Gerdes, K. 2002. Prokaryotic DNA segregation by an actin-like filament. EMBO J. 21: 3119–3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller-Jensen J., Borch, J., Dam, M., Jensen, R.B., Roepstorff, P., and Gerdes, K. 2003. Bacterial mitosis: ParM of plasmid R1 moves plasmid DNA by an actin-like insertional polymerization mechanism. Mol. Cell 12: 1477–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. 2002. Segregating sister genomes: The molecular biology of chromosome separation. Science 297: 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki H., Yamaichi, Y., and Hiraga, S. 2000. Dynamic organization of chromosomal DNA in Escherichia coli. Genes & Dev. 14: 212–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen T., Yan, A.W., Gale, G., and Goldberg, M.B. 2005. Presence of multiple sites containing polar material in spherical Escherichia coli cells that lack MreB. J. Bacteriol. 187: 6187–6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson T. and Aebi, U. 2002. Actin in the nucleus: What form and what for? J. Struct. Biol. 140: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S.K. and Hansen, F.G. 1991. A missense mutation in the rpoC gene affects chromosomal replication control in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173: 5200–5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T.D. 2003. The cytoskeleton, cellular motility and the reductionist agenda. Nature 422: 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T.D. and Borisy, G.G. 2003. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell 112: 453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J., Ishihama, Y., and Mann, M. 2003. Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in proteomics. Anal. Chem. 75: 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe M.E. and Errington, J. 1999. Upheaval in the bacterial nucleoid. An active chromosome segregation mechanism. Trends Genet. 15: 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Y.L., Le, T., and Rothfield, L. 2003. Division site selection in Escherichia coli involves dynamic redistribution of Min proteins within coiled structures that extend between the two cell poles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 7865–7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarstad K., Boye, E., and Steen, H.B. 1986. Timing of initiation of chromosome replication in individual Escherichia coli cells. EMBO J. 5: 1711–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollier P.H., Thanbichler, M., McGrath, P.T., West, L., Meewan, M., McAdams, H.H., and Shapiro, L. 2004. Rapid and sequential movement of individual chromosomal loci to specific subcellular locations during bacterial DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 9257–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visa N. 2005. Actin in transcription. Actin is required for transcription by all three RNA polymerases in the eukaryotic cell nucleus. EMBO Rep. 6: 218–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachi M. and Matsuhashi, M. 1989. Negative control of cell division by mreB, a gene that functions in determining the rod shape of Escherichia coli cells. J. Bacteriol. 171: 3123–3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachi M., Doi, M., Tamaki, S., Park, W., Nakajima-Iijima, S., and Matsuhashi, M. 1987. Mutant isolation and molecular cloning of mre genes, which determine cell shape, sensitivity to mecillinam, and amount of penicillin-binding proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169: 4935–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachi M., Doi, M., Okada, Y., and Matsuhashi, M. 1989. New mre genes mreC and mreD, responsible for formation of the rod shape of Escherichia coli cells. J. Bacteriol. 171: 6511–6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachi M., Iwai, N., Kunihisa, A., and Nagai, K. 1999. Irregular nuclear localization and anucleate cell production in Escherichia coli induced by a Ca2+ chelator, EGTA. Biochimie 81: 909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.D., Schnitzer, M.J., Yin, H., Landick, R., Gelles, J., and Block, S.M. 1998. Force and velocity measured for single molecules of RNA polymerase. Science 282: 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb C.D., Teleman, A., Gordon, S., Straight, A., Belmont, A., Lin, D.C., Grossman, A.D., Wright, A., and Losick, R. 1997. Bipolar localization of the replication origin regions of chromosomes in vegetative and sporulating cells of B. subtilis. Cell 88: 667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb C.D., Graumann, P.L., Kahana, J.A., Teleman, A.A., Silver, P.A., and Losick, R. 1998. Use of time-lapse microscopy to visualize rapid movement of the replication origin region of the chromosome during the cell cycle in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 28: 883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.J. and Errington, J. 2003. RacA and the Soj–Spo0J system combine to effect polar chromosome segregation in sporulating Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 1463–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaichi Y. and Niki, H. 2000. Active segregation by the Bacillus subtilis partitioning system in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 14656–14661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2004. migS, a cis-acting site that affects bipolar positioning of oriC on the Escherichia coli chromosome. EMBO J. 23: 221–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavriev S.K. and Shemyakin, M.F. 1982. RNA polymerase-dependent mechanism for the stepwise T7 phage DNA transport from the virion into E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 10: 1635–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]