Abstract

Long Interspersed Element-1 (LINE-1 or L1) retrotransposons encode proteins required for their mobility (ORF1p and ORF2p), yet little is known about how L1 mRNA is translated. Here, we show that ORF2 translation generally initiates from the first in-frame methionine codon of ORF2, and that both ORF1 and the inter-ORF spacer are dispensable for ORF2 translation. Remarkably, changing the ORF2 AUG codon to any other coding triplet is compatible with retrotransposition. However, introducing a premature termination codon in ORF1 or a thermostable hairpin in the inter-ORF spacer reduces ORF2p translation or L1 retrotransposition to ∼5% of wild-type levels. Similar data obtained from “natural” and codon optimized “synthetic” mouse L1s lead us to propose that ORF2 is translated by an unconventional termination/reinitiation mechanism.

Keywords: L1, LINE-1, retrotransposon, translation

Long Interspersed Element-1s (LINE-1s or L1s) are a family of abundant non-long-terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons in mammalian genomes (for reviews, see Hutchison et al. 1989; Moran and Gilbert 2002). The vast majority (i.e., >99.8%) of L1s are retrotransposition defective because they are 5′ truncated, contain internal rearrangements, or harbor debilitating mutations in their open reading frames (ORFs) (Grimaldi et al. 1984; Lander et al. 2001). However, the average human genome is estimated to contain ∼80-100 retrotransposition-competent LINE-1 (RC-L1) elements (Sassaman et al. 1997; Brouha et al. 2003), and their movement continues to impact genome evolution (Kazazian et al. 1988; for review, see Ostertag and Kazazian 2001).

RC-L1s are ∼6.0 kb and have a 5′ untranslated region (UTR), two nonoverlapping ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2), and a 3′ UTR that ends in a poly(A) tail (Scott et al. 1987; Dombroski et al. 1991). ORF1 encodes a ∼40-kDa RNA-binding protein (p40 or ORF1p) (Holmes et al. 1992; Hohjoh and Singer 1996, 1997), whereas ORF2 has the potential to encode a 150-kDa protein (ORF2p) with demonstrated endonuclease and reverse transcriptase activities (Mathias et al. 1991; Feng et al. 1996). Both proteins are required in cis for retrotransposition (Moran et al. 1996), which probably occurs by target site-primed reverse transcription (RT) (Luan et al. 1993; Feng et al. 1996; Cost et al. 2002).

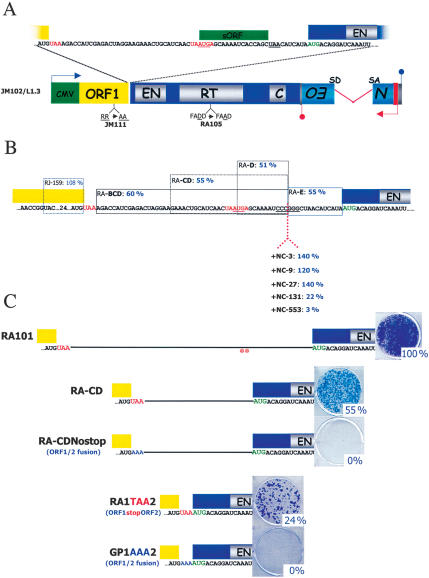

The human L1 transcript is unusual because a 63-base inter-ORF spacer that contains two in-frame stop codons separates ORF1 and ORF2 (Fig. 1A). The inter-ORF spacer also contains an out-of-frame AUG codon in a poor Kozak contex that has the potential to encode a short ORF (sORF) of six amino acids (Fig. 1A; Dombroski et al. 1991). In principle, ORF2p can be translated from either the bicistronic L1 mRNA or a post-transcriptionally modified LINE-1 transcript. However, because mutagenic L1 insertions are identical in sequence to their respective progenitors (Dombroski et al. 1991; Holmes et al. 1994) and splicing does not appear to generate subgenomic L1 RNAs that can serve as substrates for ORF2p translation (Skowronski et al. 1988; Perepelitsa-Belancio and Deininger 2003), it remains likely that ORF2p is translated from a full-length, bicistronic L1 mRNA. Indeed, results from a previous in vitro translation study led to the hypothesis that an internal ribosome entry sequence (IRES) in the L1 inter-ORF spacer is required for human ORF2p translation (McMillan and Singer 1993). Moreover, the second ORF of a related non-LTR retrotransposon, SART1, appears to be translated from a bicistronic RNA (Kojima et al. 2005). Clearly, a fundamental understanding of how ORF2p is translated remains an open question, and answering it is critical to fully understand L1 biology.

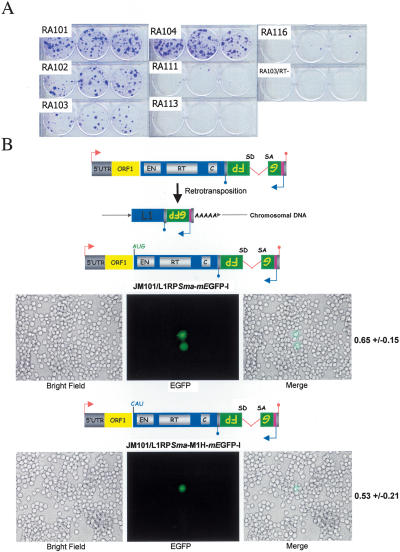

Figure 1.

The 3′ end of ORF1 and the inter-ORF spacer are dispensable for L1 retrotransposition. (A) Schematic of an RC human L1: The cartoon depicts the structure of JM102/L1.3. The yellow and blue rectangles represent ORF1 and ORF2, respectively. EN, RT, and C represent the approximate positions of the endonuclease, reverse transcriptase, and cysteine-rich domains of ORF2, respectively. The green rectangle indicates the CMV immediate early promoter used to drive L1 expression. The blue lollipop indicates the SV40 polyadenylation sequence downstream of the L1 3′ UTR (gray rectangle). The 3′ UTR of the L1 is tagged with a retrotransposition indicator cassette (mneoI). The indicator cassette consists of a backward copy of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene that contains its own promoter (red arrow) and polyadenylation signal (red lollipop). The neomycin phosphotransferase gene also is interrupted by intron 2 from the γ-globin gene, which is in the same transcriptional orientation of the L1. SD and SA represent the splice donor and splice acceptor sequences of the intron, respectively (Freeman et al. 1994). This arrangement ensures that G418-resistant foci will arise only if the primary L1 RNA transcript is spliced and then undergoes retrotransposition (Moran et al. 1996). The approximate positions of two mutations that render the L1 retrotransposition-defective (JM111 and RA105) are indicated below the schematic (Moran et al. 1996). The sequence of the 63-base inter-ORF spacer is magnified above the schematic. Red lettering indicates stop codons at the end of ORF1 and in the inter-ORF spacer. The red underlining signifies an AUG codon in the inter-ORF spacer that can, in principle, initiate the translation of a short ORF (green box) of six codons. Green lettering indicates the first in-frame AUG codon in ORF2. (B) Mutations in the inter-ORF spacer have little effect on retrotransposition. Constructs containing a 30-base deletion of the 3′ end of ORF1 (RJ159) or nonoverlapping partial deletions of the inter-ORF spacer (RA-BCD, Δ19 bases; RA-CD, Δ17 bases; RA-D, Δ13 bases; RA-E, Δ14 bases) are indicated by the rectangles (see the Supplemental Material). Insertion mutations in the inter-ORF spacer are indicated below the schematic. Blue numbering indicates the relative retrotransposition efficiencies of each construct. (C) ORF1 and ORF2 need to be separated by a stop codon for efficient retrotransposition. Representative data showing the relative retrotransposition efficiencies of the wild-type construct (RA101), a mutant containing a partial deletion of the inter-ORF spacer (RA-CD), a mutant lacking the inter-ORF spacer (RA1TAA2), and mutants containing an in-frame fusion between ORF1 and ORF2 (RA-CDNostop and GP1AAA2, respectively) are indicated next to the cartoons of each construct. The relative retrotransposition efficiency is indicated and is compared with the relative retrotransposition efficiency of the wild-type control (RA101).

The cis-preference model of L1 retrotransposition predicts that as few as one molecule of ORF2p is made per L1 RNA transcript (Wei et al. 2001; Moran and Gilbert 2002). Consistent with this notion, ORF2p has been notoriously difficult to detect both in vitro and in vivo. ORF2p is probably not synthesized as an ORF1p-ORF2p fusion protein, as antisera reactive to native ORF1p or to an epitope-tagged version of ORF1p have only identified a ∼40 kDa product (Leibold et al. 1990; McMillan and Singer 1993; Hohjoh and Singer 1996; Goodier et al. 2004; Kulpa and Moran 2005). Immunoprecipitation experiments have allowed the detection of a low level of ORF2p as a single polypeptide of ∼130 kDa (Ergun et al. 2004); however, whether this protein is derived from an RC-L1 remains uncertain. More recently, expression analyses using a vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system failed to detect ORF2p from a full-length L1 despite detecting an abundant level of ORF1p (Goodier et al. 2004).

By employing a cultured cell retrotransposition assay as a genetic readout for ORF2p translation (Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2000), we have demonstrated that the first in-frame AUG codon in ORF2 is used to initiate translation, and that sequences within ORF1 or the inter-ORF spacer are dispensable for both L1 retrotransposition and ORF2 translation. Remarkably, mutating the AUG codon to one specifying any other amino acid still allows for efficient L1 retrotransposition in HeLa, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), and rat neural progenitor cells. In contrast, a premature termination codon in ORF1 or the insertion of a stable hairpin into the inter-ORF spacer that blocks the translocation of scanning ribosomes severely reduces ORF2p translation or L1 retrotransposition efficiency. Finally, we provide evidence that both “natural” and codon optimized “synthetic” L1s also can initiate ORF2 translation in an AUG-independent manner. These and other data we present strongly suggest that LINE-1 ORF2 is translated by an unconventional termination/reinitiation mechanism. It is possible that other mammalian genes may be translated by a similar mechanism, which would impact the complexity of the proteome.

Results

The 3′ end of ORF1 and the inter-ORF space are dispensable for ORF2p translation

Previous work suggested that the inter-ORF spacer contains cis-acting sequences important for ORF2 translation (McMillan and Singer 1993). To test this hypothesis, we deleted sequences from either the 3′ end of ORF1 or the inter-ORF spacer of L1.3 and assayed the resultant constructs for retrotransposition in a quantifiable genetic cell-based assay (see Supplementary Fig. 1; Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2000). Deletion of 30 nucleotides (nt) from the 3′ end of ORF1 did not significantly affect retrotransposition (RJ159) (Fig. 1B), whereas partial deletions of sequences in the inter-ORF spacer only reduced retrotransposition to ∼50% of wild-type levels (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Similarly, increasing the length of the inter-ORF sequence by up to 131 nt only reduced retrotransposition to ∼22% of wild-type levels (+NC-131) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, a 553-nt insertion reduced retrotransposition to ∼3% of wild-type levels (+NC-553) (Fig. 1B). Finally, to determine if the inter-ORF sequence is dispensable for retrotransposition, we generated a construct in which ORF1 and ORF2 are separated by a single stop codon (RA1TAA2) (Fig. 1C). Retrotransposition of the resultant mutant was reduced to ∼24% the level of the wild-type control. Together, these data argue strongly against an essential IRES in either the 3′ end of ORF1 or the inter-ORF spacer that is necessary for ORF2 translation, but do suggest that the size of the inter-ORF spacer influences both ORF2 translation and L1 retrotransposition efficiency.

Table 1.

Results from the cis-based L1 retrotransposition assay

| Clone | Description | % of RA101 | SD | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human LINE-1 cis-retrotransposition | ||||

| RA101 | Wild type | 100 | — | >3 |

| RA105 | RT (−) | 0 | — | >3 |

| JM111 | ORF1 (−) | 0 | — | >3 |

| RJ-159 | ORF1 C-term deletion | 108 | 5.0 | >3 |

| RA-BCD | Inter-ORF deletion | 60 | 14.7 | 3 |

| RA-CD | Inter-ORF deletion | 55 | 2.4 | 3 |

| RA-D | Inter-ORF deletion | 51 | 4.6 | 3 |

| RA-E | Inter-ORF deletion | 55 | 13.1 | 3 |

| RA1taa2 | Inter-ORF deletion | 24 | 1.5 | >3 |

| GP1aaa2 | ORF1 and ORF2 fused | 0 | — | >3 |

| RA-CDNostop | ORF1 and ORF2 fused | 0 | — | >3 |

| GP-NC-3 | Inter-ORF insertion | 140 | 31.4 | 3 |

| GP-NC-9 | Inter-ORF insertion | 120 | 27.7 | 3 |

| GP-NC-27 | Inter-ORF insertion | 140 | 3.3 | 3 |

| GP-NC-131 | Inter-ORF insertion | 22 | 11.3 | 3 |

| GP-NC-553 | Inter-ORF insertion | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| RA104 | In frame stop codon upstream ORF2 AUG | 88 | 9.1 | >3 |

| RA116 | EN (−) | 0.3 | 1 | >3 |

| RA113 | Frameshift stop at position 11 of ORF2 | 0 | — | >3 |

| RA189 | ORF2 IT 8-9 XX | 0 | — | >3 |

| RA167 | ORF2 SH 6-7 XX | 0.1 | 1.1 | >3 |

| RA145 | ORF2 SN 4-5 XX | 0.8 | 2.8 | >3 |

| RA123 | ORF2 TG 2-3 XX | 1.2 | 2.8 | >3 |

| RA111 | ORF2 M1X | 1.9 | 2 | >3 |

| RA-PXX | ORF2 MTG 1-3 PXX | 2 | 5.4 | >3 |

| RA103/RT- | M1P/RT- | 0 | — | 3 |

| RA111/RT- | M1X/RT- | 0 | — | 3 |

| RA101Schloop | Inter-ORF hairpin insertion | 5 | 1.7 | >3 |

| RA103Schloop | Inter-ORF hairpin insertion/M1P | 2 | 1 | >3 |

| GP101 NaugGNostop | Better AUG Kozak in the sORF of Inter-ORF; no stop in sORF | 130 | 12 | >3 |

| GP101-Aaug VG | Optimal Kozak AUG in the inter-ORF (out of frame) | 102 | 10 | >3 |

| GP101-DAcug | ORF2 control mutant | 100 | — | >3 |

| GP101-DAaugVG | Optimal Kozak AUG in ORF2 (out of frame) | 105 | 5 | >3 |

| GP103-AaugVG | Optimal Kozak AUG in the inter-ORF (out of frame); M1P | 12.7 | 4 | >3 |

| GP103-DAcug | ORF2 control mutant; M1P | 100 | — | >3 |

| GP103-DAaugVG | Optimal Kozak AUG in ORF2 (out of frame); M1P | 85 | 3.6 | >3 |

| RA-UAAg | Restores “backward” frame in M1X | 39 | 1.4 | >3 |

| RA-UAuAg | Destroy “backward” frame in M1X | 3 | 2.8 | >3 |

|

|

Mouse LINE-1 cis-retrotransposition

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | Description | % of pCEPL1SM | SD | n |

| pCEPL1SM | Wild type | 100 | — | >3 |

| pCEPL1SM-N21A | EN (−) | 1.3 | 1.1 | >3 |

| pCEPL1SM-IS18-19XX | ORF2 IS 18-19 XX | 0.9 | 0.5 | >3 |

| pCEPL1SM-M1P | ORF2 M1P | 92 | 8 | >3 |

| pCEPL1SM-M1H | ORF2 M1H | 102 | 11.7 | 3 |

| pCEPL1SM-M1X | ORF2 M1X | 101 | 5.9 | >3 |

| Clone | Description | % of pCEPTGf21Pac | SD | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCEPTGf21 | Wild type | 125 | 23.4 | >3 |

| pCEPTGf21Pac | Wild type + PacI | 100 | — | >3 |

| pCEPTGf21PacM1P | ORF2 M1P | 21 | 6.7 | 3 |

| pCEPTGf21PacM1X | ORF2 M1X | 27 | 5.9 | 3 |

Column 1 indicates the name of the construct. Column 2 provides a brief description of each construct. Column 3 indicates the retrotransposition of each construct with respect to the wild-type control (RA101). Column 4 indicates the standard deviation. Column 5 indicates the number of times each construct was assayed for retrotransposition. Retrotransposition assays were conducted either with 2 × 105, 2 × 104, and/or 2 × 103 HeLa cells.

ORF1 and ORF2 need to be encoded separately for efficient retrotransposition

To investigate whether ORF1 and ORF2 need to be coded separately, we mutated the ORF1 UAA stop codon to AAA in the construct lacking the L1.3 inter-ORF spacer, thereby enabling the synthesis of an ORF1-ORF2 fusion protein (GP1AAA2) (Fig. 1C). The resultant mutant was defective for retrotransposition. A similar result was observed when we removed the stop codon from the end of ORF1 in a construct containing a partial deletion of the inter-ORF spacer (cf. RA-CD and RA-CDNostop) (Fig. 1C). Subsequent control experiments demonstrated that expression of the fusion protein did not significantly affect HeLa cell viability (data not shown), and that the fusion protein is functional as assayed in a genetic trans-complementation assay (see Fig. 6B, below; Supplementary Table 2). Thus, these data indicate that the presence of a stop codon between ORF1 and ORF2 is required for retrotransposition.

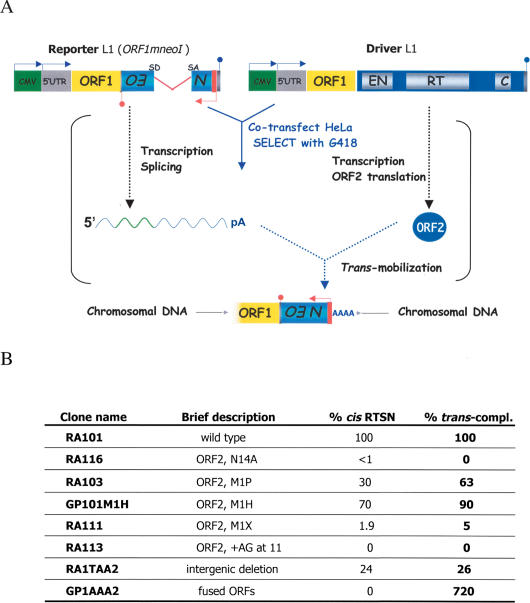

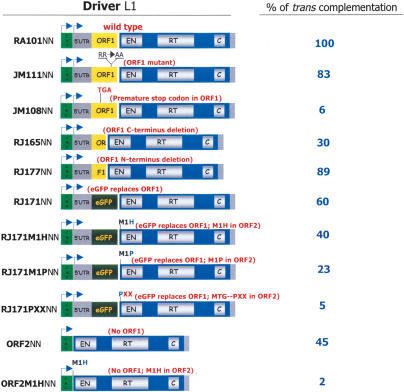

Figure 6.

An independent assay to monitor ORF2p translation. (A) Schematic of the trans-complementation assay. To assay for trans-complementation, wild-type and mutant L1 constructs lacking the mneoI indicator cassette (i.e., driver elements; cartoon on the right) were cotransfected into HeLa cells with a construct consisting of the L1 5′ UTR, ORF1, and the mneoI indicator cassette (ORF1mneoI). We previously demonstrated that ORF1mneoI RNA is a preferential substrate for authentic trans-complementation (Wei et al. 2001). G418-resistant foci only will arise if ORF1mneoI RNA is trans-mobilized by the ORF2 protein provided by the driver L1 lacking the indicator cassette. (B) Positive correlation between results obtained with the cis-based retrotransposition and trans-complementation assays. Column 1 of the inset table indicates the name of each construct. Column 2 provides a brief description of each construct. Column 3 indicates the retrotransposition efficiency of each construct obtained in the cis-based retrotransposition assay. Column 4 indicates the trans-complementation efficiency of each construct. A positive correlation is seen between the results gained from the two assays. Because we are detecting fewer G418-resistant foci in the trans-complementation assay, we encounter a larger standard error when compared with the cis-based retrotransposition assay.

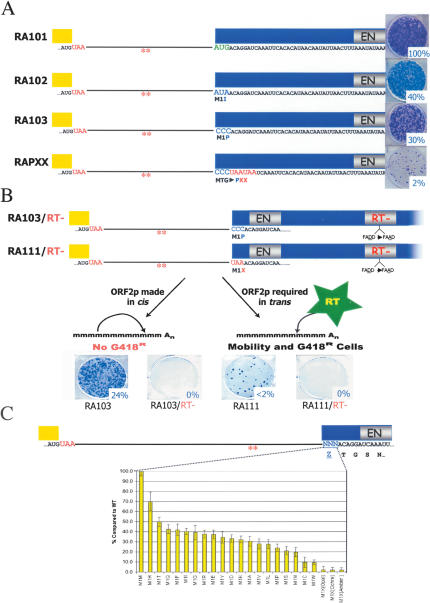

Mapping the ORF2p translation initiation site

We next sought to determine the boundaries of ORF2p translation initiation. Previous experiments demonstrated that a conserved asparagine residue (N14) is important for both L1.2 endonuclease activity in vitro and retrotransposition in cultured cells (Feng et al. 1996; Moran et al. 1996). Consistently, an analogous missense mutation in L1.3 (N14A) reduced retrotransposition to <0.3% of wild-type control levels (RA116) (Fig. 2). These data suggest that ORF2p translation initiates upstream of N14 and effectively rules out the possibility of translational initiation from the next in-frame AUG at codon 99 in ORF2, which is located downstream of catalytic amino acids critical for endonuclease function.

Figure 2.

ORF2p translation starts at the first in-frame AUG codon of ORF2. The schematic depicts cartoons of each of the mutant constructs tested in the retrotransposition assay. The red asterisks signify the two stop codons in the inter-ORF spacer. The relative position of each mutation is shown below the cartoons. The construct names are indicated in the left column, and representative data from the cultured cell retrotransposition assay are indicated at the right of the figure. The relative retrotransposition efficiency is indicated in the parenthesis and is compared with the relative retrotransposition efficiency of the wild-type control (RA101). RA105 is a retrotransposition-defective L1 containing a missense mutation in the RT active site (Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2001). JM111/L1.3 is a retrotransposition-defective L1 containing a pair of missense mutations in ORF1 (Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2001).

To further refine the ORF2p initiation site, we made a series of constructs containing nonsense mutations in the 5′ end of ORF2 (Fig. 2). The placement of a frame-shift-induced termination codon at putative amino acid 11 abolished retrotransposition (RA113) (Fig. 2). The introduction of sequential in-frame termination codons at putative amino acids 8 or 6 (RA189 and RA167) (Fig. 2) reduced retrotransposition to <1% of wild-type levels. Similarly, placing sequential in-frame stop codons at putative amino acids 4 or 2 (RA145 or RA123) (Fig. 2) or replacing the putative ORF2 AUG initiation codon with a termination codon (RA111) (Fig. 2) reduced retrotransposition to 1%-2% of wild-type levels.

To map the 5′ boundary of ORF2 translation initiation, we inserted an adenosine residue in the inter-ORF region, generating an in-frame stop codon immediately upstream of the putative AUG initiation codon (RA104) (Fig. 2; Table 1). The resultant construct retrotransposed near the level of the respective wild-type control (Fig. 2; Table 1). Together, the above data suggest that ORF2p translation preferentially initiates at the first in-frame AUG codon. However, the low level or retrotransposition apparent in RA111, RA123, and RA145 indicates that ORF2p translation also can initiate less efficiently from non-AUG codons present in the 5′ end of ORF2 (Fig. 2; Table 1), and further highlights the exquisite sensitivity of the cultured cell retrotransposition assay in detecting ORF2p synthesis.

The ORF2 AUG is dispensable for retrotransposition

The low level of retrotransposition noted in the AUG-to-UAA mutant (RA111) (Fig. 2) prompted us to investigate if the ORF2 AUG codon is required for retrotransposition. Thus, we mutated it to either AUA or CCC (RA102 or RA103, respectively) (Fig. 3A) and assayed the resultant constructs for retrotransposition. Remarkably, both mutants retrotransposed at 30%-40% the levels of the wild-type control. By comparison, introducing two in-frame stop codons after the putative CCC initiation codon (RAPXX) (Fig. 3A) reduced retrotransposition to <2% of wild-type levels. These data suggest that ORF2p synthesis can initiate from a non-AUG codon in a position-dependent manner (see below).

Figure 3.

The ORF2 AUG is dispensable for retrotransposition. (A) Mutating the AUG codon to either AUA or CCC is still compatible with retrotransposition. The schematic depicts cartoons of each of the mutant constructs tested in the retrotransposition assay. The respective mutations (AUG to AUA in RA102; AUG to CCC in RA103; AUGACAGGA to CCCUAAUAA in RAPXX) are indicated below the cartoon. Construct names are indicated in the left column, and representative data from the cultured cell retrotransposition assay are indicated at the right of the figure. The relative retrotransposition efficiency is indicated and is expressed as compared with the relative retrotransposition efficiency of the wild-type control (RA101). (B) Exogenous sources of RT are not promoting retrotransposition of the mutant constructs. Double mutants containing either the M1P or M1X mutation in conjunction with an RT active site mutation (RA103/RT- or RA111/RT-) were assayed for retrotransposition. Both mutants were retrotransposition defective, indicating that ORF2p was translated in the original M1P and M1X mutants. (C) The ORF2 AUG codon can be substituted with any coding triplet. The ORF2 AUG was mutated individually so that it could encode the other 19 amino acids. Each of the resultant constructs (X-axis) retrotransposed at 10%-70% of wild-type levels (Y-axis). By comparison, mutating the AUG to each stop codon (Opal, Ochre, and Amber) reduced retrotransposition by ∼50-fold. The percent of retrotransposition is shown compared with the wild-type element RA101 (i.e., M1M in the bar graph). The error bars indicate the standard deviation, which was calculated from at least six independent experiments for each construct.

To rule out that an exogenous RT was promoting retrotransposition of the RA103 and RA111 mutants, we constructed double mutants that also contain a missense mutation in the RT active site (RA103/RT- and RA111/RT-) (Fig. 3B) and assayed them for retrotransposition. We reasoned that if an exogenous RT was promoting retrotransposition that both the single and double mutants would retrotranspose at similar levels. However, both double mutants were defective for retrotransposition, indicating that ORF2p is being synthesized in cis in the original RA103 and RA111 constructs (Fig. 3B). Subsequent control experiments revealed that retrotransposition events derived from the RA103 and RA111 constructs retain the original mutation (Supplementary Fig. 2) and that similar steady-state levels of L1 RNA are present in HeLa cells transfected with either the wild-type or mutant constructs (Supplementary Fig. 3A; Wei et al. 2001). We conclude that ORF2p was translated from the mutant RNAs and that those RNAs remain retrotransposition competent.

To further investigate the plasticity of the ORF2 AUG initiation codon, we independently mutated it to codons specifying the other 19 amino acids and three stop codons. Remarkably, each missense mutant retained the ability to retrotranspose at 10%-70% of wild-type levels (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table 1). By comparison, each nonsense mutant reduced retrotransposition to <2% of wild-type levels (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table 1). To confirm that G418 selection was not promoting artifactual translation from the mutant constructs, we also demonstrated that both the wild-type and a M1H mutant constructs retrotransposed at comparable efficiencies in an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-based retrotransposition assay conducted in the absence of translation inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, these data indicate that the context of the ORF2 AUG codon is important for specifying ORF2 initiation, but that any amino acid can substitute for methionine.

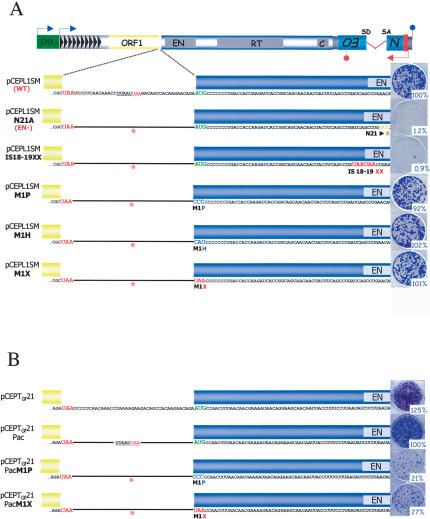

The ORF2 AUG of synthetic and natural mouse L1s is dispensable for retrotransposition

We next tested whether the ORF2 AUG codon was dispensable for ORF2p synthesis in a codon-optimized synthetic mouse L1, which exhibits high-frequency retrotransposition in cultured cells (Han and Boeke 2004). The mouse ORF2 protein is predicted to have an N-terminal extension of seven amino acids when compared with its human counterpart (Naas et al. 1998; Moran and Gilbert 2002). As noted for human L1s, retrotransposition was reduced to <1% of wild-type levels when a missense mutation was introduced in the endonuclease domain (N21A) of ORF2 or when sequential termination codons were introduced at the putative 18th codon of ORF2 (IS18-19XX) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, mutating the putative AUG initiation codon to CCC (proline), CAU (histidine), or a stop codon (UAA) had no detectable effect on retrotransposition (Fig. 4A; see Discussion).

Figure 4.

AUG-independent translation is not peculiar to human L1 elements. (A) AUG-independent translation of a synthetic mouse L1. A schematic of a synthetic mouse L1 is shown at the top of the figure (Han and Boeke 2004). The synthetic mouse L1 contains its own promoter (gray rectangles with arrows) as well as a heterologous cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter (green rectangle). It also contains the SV40 polyadenylation sequence (blue lollipop) downstream of its 3′ UTR (gray box). The sequence of the 40-nt inter-ORF spacer is magnified below the schematic. The red lettering indicates stop codons at the end of ORF1 and in the inter-ORF spacer. The red asterisk subsequently is used to indicate the relative position of the stop codon in the inter-ORF spacer. The 5′ end of ORF2 contains a 21-nt extension (coding for seven amino acids) when compared with a human RC-L1. The green lettering indicates the first in-frame AUG codon in ORF2. The relative position of each mutation is shown below the cartoons. The construct names are indicated in the left column, and representative data from the cultured cell retrotransposition assay are indicated at the right of the figure. The relative retrotransposition efficiency of each mutant is reported relative to the retrotransposition efficiency of the wild-type control (pCEPL1SM). pCEPL1SM N21A is a retrotransposition-defective L1 containing a missense mutation of an amino acid critical for L1 endonuclease function (Feng et al. 1996). (B) AUG-independent translation of a natural mouse L1. A schematic of a natural mouse L1 (pCEPTGf21) is shown at the top of the figure (Goodier et al. 2001). Labeling is the same as in A. A PacI restriction site (underlined) was introduced in the inter-ORF spacer of the TGf21 element (pCEPTGf21Pac) to generate a stop codon between ORF1 and ORF2 (red letter and red asterisks). The PacI site does not significantly affect retrotransposition and makes the expression context of the resultant construct (pCEPTGf21Pac) similar to the synthetic mouse L1 in A. The retrotransposition efficiencies of the M1P and M1X mutants are reported with respect to the retrotransposition efficiency of the corresponding control (pCEPTGf21Pac).

To determine whether the above results were peculiar to the synthetic L1, we generated similar mutations in a “natural mouse” L1, TGF21, which also is capable of high-efficiency retrotransposition in human cells (Goodier et al. 2001). Mutating the putative AUG initiation codon to either CCC (proline) or UAA (stop) still allowed retrotransposition at ∼20%-30% of the levels of the wild-type control (Fig. 4B). Thus, although slight differences exist between the synthetic and natural mouse mutant constructs (see Discussion), the data indicate that the AUG codon is dispensable in mouse L1s for both ORF2 translation and retrotransposition.

AUG-independent translation is not peculiar to HeLa cells

To test whether AUG-independent ORF2 translation is peculiar to HeLa cells, we transfected representative mutant constructs into either CHO cells or rat neuronal progenitor cells. In both cell types, we observed qualitatively similar trends in retrotransposition when compared with data obtained from HeLa cells (Fig. 5A,B), indicating that the phenomenon of AUG-independent L1 retrotransposition/translation is not peculiar to either human or transformed cells.

Figure 5.

ORF2 AUG-independent translation is not peculiar to human or transformed cells. A representative group of mutant constructs were assayed for retrotransposition in CHO (CHO-1) cells (A) and rat neural progenitor cells (B). In B, the percentage of EGFP-positive cells and standard deviation are indicated in the figure. In all instances, the results were similar to those obtained in HeLa cells.

ORF2p translation does not depend on ORF1 or ORF1p

To establish an independent assay to monitor L1 ORF2p production, we initially fused a luciferase reporter cassette lacking an AUG codon in frame with human ORF2, thereby allowing for the production of an ORF2-luciferase fusion protein. The resultant construct contains ORF1, the L1 inter-ORF spacer, and the first 189 nt of ORF2 and is similar to a construct used previously in ORF2 translation studies (McMillan and Singer 1993). However, despite repeated attempts to optimize this assay, the signal-to-noise ratio remained low, prohibiting a confident quantitative assessment of ORF2p production.

To overcome the limitations of the above assay, we next exploited a genetic trans-complementation assay to monitor ORF2p production (Fig. 6A; Wei et al. 2001). The assay monitors the ability of either a wild-type or mutant L1 construct lacking the retrotransposition indicator cassette (i.e., a driver L1) to trans-mobilize a reporter mRNA consisting of the L1 5′ UTR, ORF1, and the spliced mneoI indicator cassette (ORF1mneoI). We previously demonstrated that ORF1mneoI RNA is a preferential substrate for authentic trans-complementation by ORF2p (Wei et al. 2001). Notably, although L1 trans-complementation is a relatively rare event (∼0.5% of the retrotransposition efficiency of a wild-type L1 in cis), the assay yields hundreds of G418-resistant foci, only requires ORF2p function, and allows reliable quantification of ORF2p synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 5). Indeed, control experiments demonstrated a strong correlation between results generated in the cis- and trans-complementation assays, with the only exception being GP1AA2, which produces a functional ORF1/ORF2p fusion protein but is unable to undergo retrotransposition in cis (Figs. 1C, 6B).

The trans-complementation assay allowed us to test whether sequences within ORF1 or a functional ORF1p are required for ORF2 translation. Mutating amino acids critical for ORF1p function (JM111NN) (Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2001) had little effect on trans-complementation (i.e., ORF2p production), whereas the introduction of a premature stop codon in ORF1 (JM108NN) (Moran et al. 1996; Wei et al. 2001) resulted in a drastic reduction in trans-complementation (Fig. 7). Thus, these data suggest that the ability to translate ORF1 in its entirety, but not its functionality, is required for ORF2p translation. Indeed, constructs containing only the 5′ (RJ165NN) or 3′ (RJ177NN) end of ORF1 still were able to function as source of ORF2p in the trans-complementation assay (Fig. 7). Finally, we determined that neither the 5′ UTR nor 3′ UTR of the driver L1 is needed for ORF2p translation, although the presence of the 5′ UTR in the driver L1 did result in a greater efficiency of trans-complementation (data not shown).

Figure 7.

A nonspecific upstream ORF facilitates ORF2p translation. The names and schematics of wild-type and mutant driver elements used in the trans-complementation assay are indicated at the left of the figure. The relative trans-complementation efficiency of each construct is compared with its respective wild-type control (RA101NN) and is indicated at the right of the figure.

The above data suggest that specific sequences in ORF1 are not required for ORF2 translation. Therefore, we asked if we could replace ORF1 in its entirety with a heterologous ORF (i.e., the EGFP reading frame) (Fig. 7). The resultant construct (RJ171NN) enabled efficient trans-complementation, as did mutant constructs in which ORF1 has been replaced by the EGFP gene and the putative ORF2 initiation codon was changed to either histidine (RJ171M1HNN) or proline (RJ171M1PNN). However, introducing sequential stop codons after the M1P mutation (RJ171PXXNN) reduced trans-complementation to near background levels (Fig. 7). Control semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments showed that each of these mutant RNAs was present at similar steady-state levels in HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

After establishing that sequences in ORF1 are not needed for ORF2p translation, we next asked if mutating the initiator methionine in a construct lacking ORF1 would affect trans-complementation. Consistent with previous data, expression of wild-type ORF2 from a heterologous CMV promoter allowed efficient trans-complementation (ORF2NN) (Fig. 7), presumably by allowing it to be translated by conventional cap-dependent translation from the monocistronic mRNA (Wei et al. 2001). However, expression of the corresponding M1H, M1Y, or M1W mutant (ORF2M1HNN; ORF2M1YNN; ORF2M1WNN) from a similar context did not support trans-complementation (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table 2). Thus, these data indicate that AUG-independent translation of ORF2 is facilitated by the presence of a nonspecific upstream ORF, and argue against the presence of a self-contained IRES within the 5′ end of ORF2.

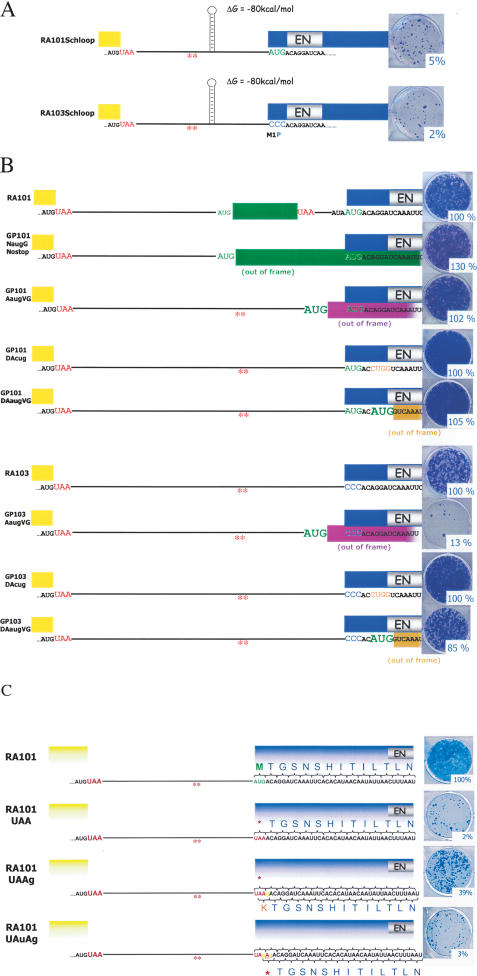

ORF2p appears to be translated by termination reinitiation

The above data suggest that ORF2 is translated by an unconventional termination/reinitiation mechanism. As an additional test of this hypothesis, we introduced a 95-base thermostable hairpin lacking AUG codons, which is known to efficiently inhibit the translocation of scanning ribosomes (Yueh and Schneider 1996), into the inter-ORF spacer of either a wild-type (RA101Schloop) or a M1P mutant (RA103Schloop) construct (Fig. 8A). The resultant constructs retrotransposed at <5% of wild-type controls (Table 1). By comparison, inserting a relatively unstructured 131-base sequence lacking AUG codons at the same position of the inter-ORF spacer allowed retrotransposition at ∼22% of wild-type levels (+NC-131) (see Fig. 1B; Table 1). Thus, impeding the translocation of scanning ribosomes severely reduces ORF2p synthesis.

Figure 8.

ORF2p translation appears to occur by an unconventional termination reinitiation mechanism. (A) A thermostable hairpin in the inter-ORF spacer inhibits ORF2 translation. A 95-base thermostable hairpin (ΔG = -80 kcal/mol) lacking AUG codons that is known to efficiently inhibit the translocation of scanning ribosomes (Yueh and Schneider 1996) was inserted into the inter-ORF spacer of either a wild-type (RA101Schloop) or a mutant (RA103Schloop) construct. Construct names are indicated in the left column, and representative data from the cultured cell retrotransposition assay are indicated at the right of the figure. The relative retrotransposition efficiency is indicated and is expressed as compared with the relative retrotransposition efficiency of the wild-type control (RA101). (B) An out-of-frame AUG codon in the inter-ORF spacer does not inhibit ORF2p translation initiation from the natural AUG codon. An out-of-frame AUG codon (green lettering) that would direct the synthesis of an irrelevant polypeptide with respect to L1 retrotransposition (reading frames are indicated by the green, purple, and gold rectangles, respectively) was placed in either the inter-ORF spacer (GP101NaugGNostop or GP101AaugVG, respectively) or downstream of the natural ORF2p initiation codon (GP101DAaugVG). Neither modification had a significant effect on L1 retrotransposition. Placement of an out-of-frame AUG codon upstream of the M1P mutant (GP103AaugVG) inhibited retrotransposition to ∼13% the level of its respective control (RA103); however, introducing an out-of-frame AUG codon downstream of the mutant (GP103DAaugVG) had no significant effect on retrotransposition. (C) Suppression of a nonsense mutation at the ORF2p initiation codon by a single base insertion. Insertion of a guanosine residue after the UAA stop codon (denoted by the gold lettering in RA101UAAg) restored retrotransposition to 39% of wild-type levels. Reintroducing a stop codon at the ORF2p initiation codon (denoted by the gold lettering in RA101UAuAg) reduced retrotransposition to 3% of the level of the wild-type control (RA101).

We next tested whether the placement of an out-of-frame AUG codon in the inter-ORF spacer would compete with the natural AUG codon for ORF2p translational initiation. Removing the stop codon from the sORF in the inter-ORF spacer (GP101NaugGNostop) or placing an out-of-frame AUG codon in an optimal Kozak context 7 nt upstream of the natural AUG codon (GP101AaugVG) had no significant effect on retrotransposition (Fig. 8B; see Supplemental Material for construct details). Placement of an out-of-frame AUG codon upstream of the M1P mutant construct (Fig. 8B; GP103AaugVG) reduced retrotransposition to ∼13% of the level of the corresponding control (RA103). In contrast, introducing an out-of-frame AUG codon downstream of the ORF2p translation initiation site did not affect retrotransposition of the wild-type or M1P mutant construct (Fig. 8B; GP101DAaugVG or GP103DAaugVG). Together, these data suggest that ORF2p translation normally occurs by termination/reinitiation and that the context of the natural AUG codon is important for translation initiation.

To exam if cis-acting sequences in ORF2 may act to position incoming ribosomes at the ORF2p translation initiation site, we tested if we could suppress the retrotransposition defect present in an M1X mutant (Fig. 8C, RA101UAA) construct by introducing a single base downstream of the UAA codon that would reinstate the reading frame if read using a “backward scanning” mechanism (Fig. 8C, RA101UAAg). Remarkably, the single base mutation suppressed the original UAA mutant and restored retrotransposition to 39% of wild-type levels. As predicted by our model, introducing a second point mutation to reinstate a stop codon at the site of translation initiation (Fig. 8C, RA101UAuAg) reduced retrotransposition back to 3% of wild-type levels. Thus, the most parsimonious interpretation of all our data is that ORF2p translation occurs by an unconventional termination/renitiation mechanism, and that sequences within ORF2 may play a role in positioning the ribosome at or near the natural ORF2 AUG codon.

Discussion

The cis-preference model of L1 retrotransposition predicts that as little as one molecule of ORF2p is synthesized per L1 RNA (Wei et al. 2001) and it has been difficult to detect human ORF2p from an RC-L1 using conventional biochemical methods. McMillan and Singer (1993) demonstrated that an ORF2p/lacZ fusion protein could be detected at low levels in a colorimetric colony assay when expressed from a transfected bicistronic L1 reporter construct. The placement of a thermostable hairpin upstream of ORF1 had little effect on ORF2p/lacZp synthesis, whereas a premature termination codon in ORF1 eliminated ORF2p/lacZp production. These data led the authors to speculate that ORF2p is synthesized as a separate polypeptide by termination/reinitiation or through the use of an IRES, which may be located within the inter-ORF spacer (McMillan and Singer 1993). Consistently, Ergun et al. (2004) demonstrated that ORF2p can be detected in immunoprecipitation experiments as a ∼130-kDa protein, suggesting that it is not made as an ORF1p/ORF2p fusion protein. However, neither of these studies attempted to identify cis-acting sequences in human L1 RNA critical for ORF2p translation.

We used a cultured cell retrotransposition assay to identify cis-acting sequences required for both ORF2p translation and L1 retrotransposition. Although the genetic assays we have employed can be criticized for providing an indirect readout of ORF2p translation, the cultured cell retrotransposition assay is exquisitely sensitive and has an advantage when compared with conventional bicistronic reporter assays because it allows a quantifiable, biologically relevant “readout” of ORF2p production. We have shown that the first in-frame methionine codon of ORF2 usually is used to initiate translation, but that changing it to any other amino acid is compatible with L1 retrotransposition. We further have demonstrated that ORF1 and the inter-ORF spacer are dispensable for both ORF2p synthesis and L1 retrotransposition. However, the presence of a premature termination codon in ORF1 or the placement of a thermostable hairpin in the inter-ORF spacer, which blocks translocation of scanning ribosomes, resulted in a 20- to 50-fold reduction in ORF2p translation or L1 retrotransposition.

Data from the current and previous studies lead us to conclude that human ORF2p is translated by an unconventional mechanism. It is unlikely that ORF2 is translated by a “leaky” form of cap-dependent scanning (Kozak 1987) as there are 11 in-frame AUG codons in L1 RNA before the first AUG codon of ORF2. Similarly, it is unlikely that ORF2 is translated as an ORF1p/ORF2p fusion protein by nonsense codon suppression, ribosomal frameshifting, or ribosome hopping (Gesteland and Atkins 1996; Schneider and Mohr 2003) because we can either delete the 3′ end of ORF1 or alter the spacing and/or sequence between ORF1 and ORF2 without drastically affecting retrotransposition. Consistently, no one has provided empirical evidence for the presence of an ORF1p/ORF2p fusion protein. It also is unlikely that ORF2 is translated using an IRES in ORF1 or the inter-ORF region, as both of these sequences are dispensable for L1 retrotransposition. Finally, it is unlikely that ORF2 is translated via conventional termination/reinitiation (e.g., that observed for the yeast GCN4 gene) (Hinnebusch 1997) because ORF1 is quite large (338 codons), translation does not require an AUG initiation codon, and deletion of the inter-ORF spacer does not drastically affect L1 retrotransposition. However, we cannot rule out a variation of termination/reinitiation mechanism that is employed by other types of viruses or artificial constructs that contain long upstream reading frame (Peabody and Berg 1986; Gowda et al. 1989; Horvath et al. 1990; Ahmadian et al. 2000; see below).

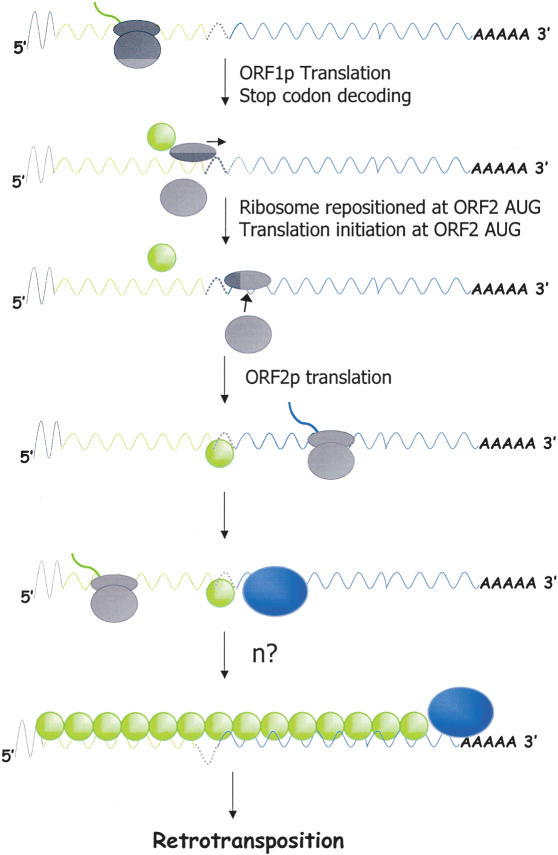

What is the mechanism of human ORF2p translation? The available data indicate that translation of an upstream ORF is needed for ORF2 translation. We speculate that the 40S subunit then scans through the inter-ORF spacer and unveils a cis-acting sequence(s) in the 5′ end of ORF2 that is used to position ribosomes at or near the ORF2 initiation codon (Fig. 9). As proposed in the ribosomal filter hypothesis (Mauro and Edelman 2002), ribosome recruitment may be mediated by a short sequence(s) near the 5′ end of ORF2, allowing ribosome assembly and ORF2 translation. Whether the ribosome that translated ORF1 is recycled for use in ORF2 translation or whether ORF2 translation is initiated by an “unindoctrinated” ribosome remains an open question. However, the finding that placement of a thermostable hairpin in the inter-ORF spacer reduces retrotransposition by ∼50-fold argues that blocking ribosomal scanning seriously compromises ORF2p synthesis (Yueh and Schneider 2000). Why a stop codon in ORF1 blocks translation of ORF2 also requires further study. However, it is possible that the premature stop codon effectively lengthens the inter-ORF spacer, disrupting retrotransposition in a manner analogous to that observed in the +NC553 mutant construct (Fig. 1B).

Figure 9.

A model for ORF2p translation. The curved line represents the polyadenylated, bicistronic L1 mRNA. The gray line indicates the 5′ UTR. The green line indicates ORF1 coding sequences. The blue line indicates ORF2 coding sequences. The gray ovals indicate the 40S and 60S subunits of the ribosome, respectively. The green and blue circles indicate ORF1p and ORF2p, respectively. Upon reaching the ORF1 stop codon, ORF1p is released from the ribosome and the ribosome is dissociated. The 40S subunit remains associated with L1 RNA and scans through the inter-ORF spacer until it reaches the first in-frame AUG in ORF2. The ribosome then is reassembled to initiate ORF2p translation. We speculate that ORF2p (or perhaps ORF1p) binding to L1 RNA inhibits ORF2 translation. This would enable ORF1p to be made at greater quantities than ORF2p so that it can coat the transcript. Remarkably, our data indicate that ORF2p translation requires a nonspecific, translatable upstream ORF and that ORF2p translation can initiate from a non-AUG codon. Other details of the model are summarized in the text.

Our working model of human L1 ORF2p translation shares similarities with those employed by other viruses and non-LTR retrotransposons. For example, the second ORF (i.e., the VP10 gene) of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) can be translated by an AUG-independent termination/reinitiation mechanism (Meyers 2003). However, unlike the situation observed for L1, VP10 translation requires sequences present in the 3′ end of the upstream ORF and not all codons support translation initiation. Similarly, the second ORF of the Bombyx mori SART1 non-LTR retrotransposon appears to be synthesized by a mechanism termed “translational coupling” (Kojima et al. 2005). However, unlike the situation observed for L1, the ORF2 AUG appears to be critical for translation. Clearly, more work is necessary to understand the mechanism of L1 ORF2 translation and its relatedness to the translation mechanisms employed by other viruses and retrotransposons.

Our data indicate that ORF2p translation generally is initiated from the first in-frame AUG codon in ORF2. However, the finding that the AUG codon can be changed to any coding triplet with only relatively minor consequences on retrotransposition efficiency is truly remarkable. In addition to the cases noted above, AUG-independent translation also has been reported for a number of viruses, including Cricket paralysis virus (Wilson et al. 2000; Pestova and Hellen 2003) and Plautia stali intestine virus (Shibuya et al. 2003), although these viruses are likely translated by different mechanisms than L1 (see above references for mechanistic details). Moreover, some non-LTR retrotransposons appear to lack an AUG initiation codon in their second ORFs (e.g., DRE-1 from Dictyostelium discoideum as well as certain RTE-retrotransposons), but the translation mechanisms of these elements remain poorly understood (Malik and Eickbush 1998; Winckler 1998).

It is clear that a conventional initiation codon provides a selective advantage for human L1s, as all “young” L1s in the Human Genome Working Draft Sequence have an AUG codon at the 5′ end of ORF2 (Badge et al. 2003). This fact does not rule out the possibility of AUG-independent ORF2 translation for naturally occurring L1s in vivo. On the contrary, because L1s lacking an ORF2 AUG codon are less efficient at retrotransposition than their wild-type counterparts, they likely will be out-competed by wild-type elements over evolutionary time, leading to their absence or gross under-representation in the extant genome (Boissinot et al. 2000).

We predict that our findings likely are not unique to human L1s. Our initial experiments indicate that both synthetic and natural mouse L1s can initiate ORF2p synthesis in an AUG-independent manner, although the efficiency of AUG-independent retrotransposition varies between the elements. Since the synthetic and natural mouse L1 sequences differ by ∼25% at the 5′ end of ORF2, it is unlikely that the enhanced retrotransposition efficiency of the synthetic L1 can be explained by the fortuitous creation of a cis-acting ribosomal recruitment site (Han and Boeke 2004). Instead, enhanced transcription or stability of the synthetic L1 RNA may allow the assembly of a greater number of L1 RNP complexes that can act as bona fide retrotransposition intermediates.

In summary, we have shown that human L1 ORF2 is translated by an unconventional mechanism. Since L1s can be considered parasitic sequences encoded by their host genome, it is unlikely that they have evolved a novel form of translation initiation. Instead, it is more likely that L1s have evolved to exploit idiosyncratic features inherent to their host genomes. As human L1s can retrotranspose in hamster, rat, and mouse cells, it is likely that we have uncovered a translation mechanism common to all mammalian genomes. If so, these data raise the possibility that other mammalian genes may be translated in a similar manner, which could impact the complexity of the proteome.

Materials and methods

Cell culture conditions

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-Glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. CHO (CHO-K1) cells were cultured in DMEM low glucose supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids. Both cell lines were grown in a humidified 7% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Rat neural progenitor cells were cultured as previously described (Muotri et al. 2005).

DNA preparation

Plasmid DNAs were purified on Qiagen midi prep columns. DNAs for transfection experiments were checked by electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose-ethidium bromide gels. Only highly supercoiled preparations of DNA (>90%) were used for transfection.

The cultured cell retrotransposition assay

The transient cultured cell retrotransposition assay was previously described (Wei et al. 2000). Briefly, HeLa cells were plated at 2 × 105, 2 × 104, and 2 × 103 in six-well tissue culture dishes. Approximately 8-14 h after plating, one set of six-well plates was cotransfected with equal amounts of a reporter plasmid (human renilla EGFP [hr-EGFP]; Stratagene) and a L1 tagged with the mneoI indicator cassette. The other set of six-well plates was transfected with only the L1 construct. We routinely used 3 μL of Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Biochemical) and 1.0 μg of DNA per transfection of HeLa cells. Seventy-two hours post-transfection, the HeLa cells in one set of six-well tissue culture plates was trypsinized and subjected to flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP cells was used to determine the transfection efficiency of each sample. The remaining set of six-well plates was subjected to G418 selection (400 μg/mL). After 12 d of daily refeeding, the selection media was aspirated, and the cells were washed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were fixed by incubation in FIX solution (2% formaldehyde [of a 37% stock solution in water], 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 1× PBS) for 30 min at 4°C. The fixed cells were stained with either 0.1% Brilliant Blue or 0.1% Crystal Violet overnight at room temperature, washed with water, and then manually counted. The retrotransposition efficiency is expressed as the number of G418-resistant foci/the number of transfected (EGFP-positive) cells. For CHO (CHO-K1) cells, the transfection conditions were identical except that ∼1 × 104 cells were plated in each well of a six-well dish, and the cells were transfected 7-8 h after seeding (Wei et al. 2000; Morrish et al. 2002). L1s tagged with the mEGFPI indicator cassette were assayed for retrotransposition as previously described (Ostertag et al. 2000). Retrotransposition in rat neural progenitor cells was performed as previously described (Muotri et al. 2005).

Trans-complementation assay

The trans-complementation assay was performed as previously described (Wei et al. 2001). Briefly, ∼6 × 106 HeLa cells were plated on a 175-cm2 tissue culture flask. Approximately 8-14 h after plating, cells were cotransfected with equal amounts of both plasmids of L1.3 ORF1mneoI and a driver L1 that lacked the mneoI indicator cassette. We routinely used 90 μL of Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Biochemical) and 30 μg of DNA per flask. Parallel cotransfection experiments of both plasmids plus hr-EGFP were used to determine the transfection efficiency of each sample (see above). Seventy-two hours post-transfection, the HeLa cells were subjected to G418 selection (400 μg/mL). After 12-14 d of daily refeeding, the selection media was aspirated and the cells were washed in 1× PBS. The cells were fixed as described above, and the resultant G418-resistant foci were counted to determine the trans-complementation efficiency.

Preparation of total RNA

Approximately 6 × 106 HeLa cells were plated in a 175-cm2 tissue culture flask. Ninety microliters of Fugene 6 transfection reagent and 30 μg of DNA were used per transfection. Approximately 48 h post-transfection the media was aspirated and the cells were washed with PBS. Attached cells were then incubated with 17.5 mL of Trizol (Invitrogen) and transferred to a clean conical vial. Homogenized samples were incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 3.5 mL of chloroform was added to the sample and the mixture was mixed vigorously by hand shaking. Samples were incubated for 3 min at room temperature and subsequently were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was placed in a new 15-mL tube containing 9 mL of isopropyl alcohol, and the resultant mixture was mixed gently by hand. This solution was incubated for 10 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 10 min. The RNA pellet was washed in 75% ethanol and then was resuspended in 300 μL of water. The resulting RNA preparation was incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 10 U of DNase I (Roche Biochemicals) prior to quantification on a Beckman DU530 spectrophotometer.

Ribonuclease protection assay

The following oligonucleotide primers were used to amplify a PCR product of ∼350 base pairs (bp) that contains ∼250 bp of complementarity to the 5′ end of L1 ORF1 sequence: JA36 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTCAACTTCTTTGCCTTTGGTTTGAATGTCC-3′) and JB3165 (5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGCAGGTTGACGCAAATGGGCGGTAGGCGTGTACGG-3′).

The resultant PCR product was purified with Gene Clean (Bio101 Systems). To generate a riboprobe, ∼1 μg of DNA product was used in an in vitro T7 transcription reaction (Ambion) that was spiked with 100 μCi of 32P-UTP and incubated for 1 h at 25°C. The resultant riboprobe was purified on a 5% polyacrylamide/6 M urea gel in TBE (Long Ranger) and was hybridized to 30 μg of total RNA with the ribonuclease protection assay (RPA) hybridization buffer (Ambion). Subsequent hybridization reactions were incubated with 150 μL of a 1:100 dilution of RNase A/T1 (Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C. The resultant products were precipitated overnight at -20°C in 225 μL of RNase inactivation precipitation buffer (Ambion). Precipitates were resuspended in gel loading buffer (Ambion) and loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gel in TBE. The gel was run at 60 W for 2 h before it was dried onto Whatman paper for 2 h at 80°C. The protected bands were detected on autoradiography film that was exposed overnight. The pTRI-Actin-Mouse riboprobe from Ambion was used as an internal control to monitor RNA integrity.

Rescue of integrants from G418R colonies

The transient retrotransposition assay was conducted as described above. After G418 selection was completed, the resultant foci from three wells of a six-well plate were trypsinized and pooled. From this pool of G418R foci, we isolated HeLa genomic DNA using the Puregene cell and tissue DNA isolation kit (Gentra). PCR reactions were conducted with a primer specific to sequences in the inter-ORF spacer of the transfected construct (5′-CTAATGAGCAAAATCCCGGGC-3′) and primer located downstream of the intron in the mneoI indicator cassette (1808AS) (Moran et al. 1996). PCR reactions contained 100 ng of genomic DNA and were conducted using the Expand Long Range PCR System (Roche Biochemical) in reaction buffer 2 (10× concentration 27.5 mM MgCl2) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. PCR was conducted in an Express thermal cycler (Hybaid), using the following cycling conditions: one cycle at 94°C for 3 min; followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 10 sec, 62°C for 30 sec, and 68°C for 6 min; and a final extension at 68°C for 30 min. PCR amplified two products: a ∼5.7-kb fragment that contained the intron in the mneoI cassette, which is derived from the original plasmid DNA, and a ∼4.9-kb fragment lacking the intron, which represents the retrotransposed product. The ∼4.9-kb product was cloned and sequenced to verify that the mutant RNAs underwent retrotransposition.

Real-time RT-PCR

One microgram of total RNA (Trizol extracted and DNaseI treated) was used for the RT reaction, which was performed using 25 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) RT (Promega) and 1 μM of an Oligo dT(12) primer at 42°C. The resultant cDNAs were used for semiquantitative PCR in an Opticon MJResearch thermal cycler, using the QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit from Qiagen. Triplicate 1/2 cDNA dilutions were used to amplify a 392-bp-long GFP fragment. Triplicate 1/100 cDNA dilutions were used to amplify a 288-bp-long GAPDH fragment. Baseline start and end cycles were assigned 5 and 8, respectively. A melting curve from 50°C to 95°C with reads every 0.2°C was performed to confirm the identity of the amplified products. The C(T) obtained from the GAPDH PCR was used to normalize the mRNA content in the samples. The GFP PCR C(T) was used to quantify the amount of mRNA produced from the transfected driver L1 element.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the University of Michigan Sequencing Core for help with sequencing and Dr. Anthony Furano, Dr. Huira Chong, Dr. Deanna Kulpa, and Ms. Amy Hulme for comments and for critically reading the manuscript. We thank Mr. David DiBardino for excellent technical assistance. We thank Haig Kazazian and John Goodier for providing the TGf21 “natural” mouse L1, Jef Boeke for providing the synthetic mouse L1 element, and Robert Schneider for providing the stable hairpin construct. Some of the initial constructs in this study were made when J.V.M. was a postdoctoral fellow in the Kazazian laboratory. The work was supported in part by a grant to J.V.M. from the National Institutes of Health (GM60518). J.L.G.P. was supported in part by a MEC/Fulbright postdoctoral grant EX-2003-0881 (MEC, Spain). The University of Michigan Cancer Center helped defray some of the DNA sequencing costs. F.H.G. was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NS052842) and the Look Out Fund.

Corresponding authors.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1380406.

References

- Ahmadian, G., Randhawa, J.S., and Easton, A.J. 2000. Expression of the ORF-2 protein of the human respiratory syncytial virus M2 gene is initiated by a ribosomal termination-dependent reinitiation mechanism. EMBO J. 19: 2681-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badge, R.M., Alisch, R.S., and Moran, J.V. 2003. ATLAS: A system to selectively identify human-specific L1 insertions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72: 823-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissinot, S., Chevret, P., and Furano, A.V. 2000. L1 (LINE-1) retrotransposon evolution and amplification in recent human history. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 915-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha, B., Schustak, J., Badge, R.M., Lutz-Prigge, S., Farley, A.H., Moran, J.V., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 2003. Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 5280-5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost, G.J., Feng, Q., Jacquier, A., and Boeke, J.D. 2002. Human L1 element target-primed reverse transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 21: 5899-5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombroski, B.A., Mathias, S.L., Nanthakumar, E., Scott, A.F., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 1991. Isolation of an active human transposable element. Science 254: 1805-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, S., Buschmann, C., Heukeshoven, J., Dammann, K., Schnieders, F., Lauke, H., Chalajour, F., Kilic, N., Stratling, W.H., and Schumann, G.G. 2004. Cell type-specific expression of LINE-1 open reading frames 1 and 2 in fetal and adult human tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 27753-27763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q., Moran, J.V., Kazazian Jr., H.H., and Boeke, J.D. 1996. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell 87: 905-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J.D., Goodchild, N.L., and Mager, D.L. 1994. A modified indicator gene for selection of retrotransposition events in mammalian cells. Biotechniques 17: 46, 48-49, 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesteland, R.F. and Atkins, J.F. 1996. Recoding: Dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65: 741-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, J.L., Ostertag, E.M., Du, K., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 2001. A novel active L1 retrotransposon subfamily in the mouse. Genome Res. 11: 1677-1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, J.L., Ostertag, E.M., Engleka, K.A., Seleme, M.C., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 2004. A potential role for the nucleolus in L1 retrotransposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13: 1041-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, S., Wu, F.C., Scholthof, H.B., and Shepherd, R.J. 1989. Gene VI of figwort mosaic virus (caulimovirus group) functions in posttranscriptional expression of genes on the full-length RNA transcript. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86: 9203-9207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, G., Skowronski, J., and Singer, M.F. 1984. Defining the beginning and end of KpnI family segments. EMBO J. 3: 1753-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.S. and Boeke, J.D. 2004. A highly active synthetic mammalian retrotransposon. Nature 429: 314-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch, A.G. 1997. Translational regulation of yeast GCN4: A window on factors that control initiator-tRNA binding to the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 21661-21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohjoh, H. and Singer, M.F. 1996. Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human LINE-1 protein and RNA. EMBO J. 15: 630-639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1997. Sequence-specific single-strand RNA binding protein encoded by the human LINE-1 retrotransposon. EMBO J. 16: 6034-6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, S.E., Singer, M.F., and Swergold, G.D. 1992. Studies on p40, the leucine zipper motif-containing protein encoded by the first open reading frame of an active human LINE-1 transposable element. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 19765-19768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, S.E., Dombroski, B.A., Krebs, C.M., Boehm, C.D., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 1994. A new retrotransposable human L1 element from the LRE2 locus on chromosome 1q produces a chimaeric insertion. Nat. Genet. 7: 143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, C.M., Williams, M.A., and Lamb, R.A. 1990. Eukaryotic coupled translation of tandem cistrons: Identification of the influenza B virus BM2 polypeptide. EMBO J. 9: 2639-2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, C.A., Hardies, S.C., Loeb, D.D., Shehee, W.R., and Edgell, M.H. 1989. LINES and related retroposons: Long interspersed sequences in the eucaryotic genome. In Mobile DNA (eds. D.E. Berg and M.M. Howe), pp. 593-617. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Kazazian Jr., H.H., Wong, C., Youssoufian, H., Scott, A.F., Phillips, D.G., and Antonarakis, S.E. 1988. Haemophilia A resulting from de novo insertion of L1 sequences represents a novel mechanism for mutation in man. Nature 332: 164-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, K.K., Matsumoto, T., and Fujiwara, H. 2005. Eukaryotic translational coupling in UAAUG stop-start codons for the bicistronic RNA translation of the non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon SART1. Mol. Cell Biol. 25: 7675-7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. 1987. An analysis of 5′-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 8125-8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulpa, D.A. and Moran, J.V. 2005. Ribonucleoprotein particle formation is necessary but not sufficient for LINE-1 retrotransposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14: 3237-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Linton, L.M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M.C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., et al. 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409: 860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, D.M., Swergold, G.D., Singer, M.F., Thayer, R.E., Dombroski, B.A., and Fanning, T.G. 1990. Translation of LINE-1 DNA elements in vitro and in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87: 6990-6994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan, D.D., Korman, M.H., Jakubczak, J.L., and Eickbush, T.H. 1993. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: A mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell 72: 595-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, H.S. and Eickbush, T.H. 1998. The RTE class of non-LTR retrotransposons is widely distributed in animals and is the origin of many SINEs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 1123-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, S.L., Scott, A.F., Kazazian Jr., H.H., Boeke, J.D., and Gabriel, A. 1991. Reverse transcriptase encoded by a human transposable element. Science 254: 1808-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, V.P. and Edelman, G.M. 2002. The ribosome filter hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 12031-12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.P. and Singer, M.F. 1993. Translation of the human LINE-1 element, L1Hs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 11533-11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, G. 2003. Translation of the minor capsid protein of a calicivirus is initiated by a novel termination-dependent reinitiation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 34051-34060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, J.V. and Gilbert, N. 2002. Mammalian LINE-1 retrotransposons and related elements. In Mobile DNA II (eds. N. Craig, et al), pp. 836-869. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Moran, J.V., Holmes, S.E., Naas, T.P., DeBerardinis, R.J., Boeke, J.D., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 1996. High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell 87: 917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish, T.A., Gilbert, N., Myers, J.S., Vincent, B.J., Stamato, T.D., Taccioli, G.E., Batzer, M.A., and Moran, J.V. 2002. DNA repair mediated by endonuclease-independent LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat. Genet. 31: 159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muotri, A.R., Chu, V.T., Marchetto, M.C., Deng, W., Moran, J.V., and Gage, F.H. 2005. Somatic mosaicism in neuronal precursor cells mediated by L1 retrotransposition. Nature 435: 903-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naas, T.P., DeBerardinis, R.J., Moran, J.V., Ostertag, E.M., Kingsmore, S.F., Seldin, M.F., Hayashizaki, Y., Martin, S.L., and Kazazian, H.H. 1998. An actively retrotransposing, novel subfamily of mouse L1 elements. EMBO J. 17: 590-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag, E.M. and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 2001. Biology of mammalian L1 retrotransposons. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35: 501-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag, E.M., Prak, E.T., DeBerardinis, R.J., Moran, J.V., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 2000. Determination of L1 retrotransposition kinetics in cultured cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 1418-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody, D.S. and Berg, P. 1986. Termination-reinitiation occurs in the translation of mammalian cell mRNAs. Mol. Cell Biol. 6: 2695-2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepelitsa-Belancio, V. and Deininger, P. 2003. RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nat. Genet. 35: 363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova, T.V. and Hellen, C.U. 2003. Translation elongation after assembly of ribosomes on the Cricket paralysis virus internal ribosomal entry site without initiation factors or initiator tRNA. Genes & Dev. 17: 181-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassaman, D.M., Dombroski, B.A., Moran, J.V., Kimberland, M.L., Naas, T.P., DeBerardinis, R.J., Gabriel, A., Swergold, G.D., and Kazazian Jr., H.H. 1997. Many human L1 elements are capable of retrotransposition. Nat. Genet. 16: 37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.J. and Mohr, I. 2003. Translation initiation and viral tricks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28: 130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.F., Schmeckpeper, B.J., Abdelrazik, M., Comey, C.T., O'Hara, B., Rossiter, J.P., Cooley, T., Heath, P., Smith, K.D., and Margolet, L. 1987. Origin of the human L1 elements: Proposed progenitor genes deduced from a consensus DNA sequence. Genomics 1: 113-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya, N., Nishiyama, T., Kanamori, Y., Saito, H., and Nakashima, N. 2003. Conditional rather than absolute requirements of the capsid coding sequence for initiation of methionine-independent translation in Plautia stali intestine virus. J. Virol. 77: 12002-12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowronski, J., Fanning, T.G., and Singer, M.F. 1988. Unit-length line-1 transcripts in human teratocarcinoma cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 1385-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W., Morrish, T.A., Alisch, R.S., and Moran, J.V. 2000. A transient assay reveals that cultured human cells can accommodate multiple LINE-1 retrotransposition events. Anal. Biochem. 284: 435-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W., Gilbert, N., Ooi, S.L., Lawler, J.F., Ostertag, E.M., Kazazian, H.H., Boeke, J.D., and Moran, J.V. 2001. Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol. Cell Biol. 21: 1429-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.E., Pestova, T.V., Hellen, C.U., and Sarnow, P. 2000. Initiation of protein synthesis from the A site of the ribosome. Cell 102: 511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winckler, T. 1998. Retrotransposable elements in the Dictyostelium discoideum genome. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 54: 383-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yueh, A. and Schneider, R.J. 1996. Selective translation initiation by ribosome jumping in adenovirus-infected and heat-shocked cells. Genes & Dev. 10: 1557-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2000. Translation by ribosome shunting on adenovirus and hsp70 mRNAs facilitated by complementarity to 18S rRNA. Genes & Dev. 14: 414-421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]