Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the suitability of microvascular flaps for the reconstruction of extensive full-thickness defects of the chest wall.

Summary Background Data:

Chest wall defects are conventionally reconstructed with pedicular musculocutaneous flaps or the omentum. Sometimes, however, these flaps have already been used, are not reliable due to previous operations or radiotherapy, or are of inadequate size. In such cases, microvascular flaps offer the only option for reconstruction.

Methods:

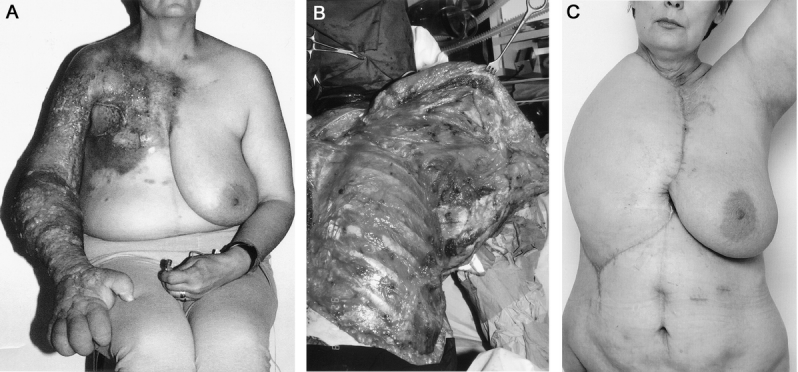

From 1988 to 2001, 26 patients with full-thickness resections of the chest wall underwent reconstruction with microvascular flaps. There were 8 soft tissue sarcomas, 8 recurrent breast cancers, 5 chondrosarcomas, 2 desmoid tumors, 1 large cell pulmonary cancer metastasis, 1 renal cancer metastasis, and 1 bronchopleural fistula. The surgery comprised 5 extended forequarter amputations, 5 lateral resections, 8 thoracoabdominal resections, and 8 sternal resections. The mean diameter of a resection was 28 cm. The soft tissue defect was reconstructed with 16 tensor fasciae latae, 5 tensor fascia latae combined with rectus femoris, and 3 transversus rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. In 2 patients with a forequarter amputation, the remnant forearm was used as the osteomusculocutaneous free flap.

Results:

There were no flap losses or perioperative mortality. Four patients needed tracheostomy owing to prolonged respiratory difficulties. The mean survival time for patients with sarcomas was 39 months and for those with recurrent breast cancer 18 months.

Conclusions:

Extensive chest wall resections are possible with acceptable results. In patients with breast cancer, the surgery may offer valuable palliation and in those with sarcomas it can be curative.

Full-thickness resection of the chest wall reconstructed with a microvascular flap was performed on 26 patients. There was no flap loss or perioperative mortality. The mean survival time of patients with sarcomas was 39 months and of those with recurrent breast cancer 18 months.

Extensive full-thickness chest wall resections are most frequently performed on patients with primary sarcomas or local recurrence of breast cancer.1,2 The chest wall is a common site for radiation-induced sarcomas3 and may also be a site for distant metastases of various malignancies. The operation may be curative, but many of the patients with chest wall malignancies do not come within the scope of curative surgical treatment. Nevertheless, they may suffer intense local pain, bleeding and discharge, infection, fetor, continuing tumor growth, or paralyzed upper extremity due to compression of their motor nerves. Such patients may be candidates for palliative resection and reconstruction.

Full-thickness defects of the chest wall must be reconstructed in a single-stage procedure to restore the bony stability and to cover the exposed vital intrathoracic organs. The goal of reconstruction is stability, water- and air-tight closure, and acceptable cosmetic appearance. Soft tissue coverage can be attained with direct closure, pedicled omentum, local skin flaps, or pedicled or free musculocutaneous flaps.4–8 The choice of reconstruction method depends on the location of the tumor, the size of the defect, and the availability of autogenous graft material.

The regional pedicled muscle flap is usually the first choice for soft tissue coverage of a chest wall defect.6,7 However, use of this flap is not feasible in all patients. Local options may already have been used, the pedicle or flap may have been damaged by previous operations or radiation therapy, or the flap may be of inadequate size to cover the defect. The larger the defect, the greater the need for microsurgical techniques. Microvascular reconstruction with a free flap may then be the only option for soft tissue coverage.

Wide defects require restoration of the stability and physiological kinetics of the chest wall. Paradoxical respiratory movement should be prevented without limiting normal breathing. For this purpose, fascial grafts, synthetic mesh, rib grafts, and “shield” prostheses (methylmethacrylate sandwiched between two sheets of prolene mesh), or their combinations, have been used.9–13

This study reviews free flap reconstructions performed at our tertiary referral center to cover full-thickness defects of the chest wall caused by oncological resections.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From 1988 to 2001, 26 patients underwent full-thickness chest wall resection and reconstruction with a free flap. The patients were admitted from other hospitals. The location and extension of the tumor and any dissemination were evaluated preoperatively with bone scanning, computed tomography, and/or magnetic resonance image scanning. The histopathological diagnosis was confirmed before surgery. Chest wall resection and reconstruction were performed in the same operation. Table 1 indicates patient and operation characteristics. Sixteen patients were operated on with curative intention. In 10 patients, the tumor had disseminated or was exceedingly extensive; these patients were operated on with palliative indication to relieve serious local symptoms. The survival of patients was calculated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier.

TABLE 1. Patient and Operation Characteristics of 26 Patients With Microvascular Reconstruction of the Chest Wall

There were 8 sternal, 5 lateral, and 8 thoracoabdominal resections of the chest wall. Five patients underwent extended forequarter amputation with resection of the ribs. The average number of ribs resected was 3.9 (range 1–6). The mean area of soft tissue resection was 503 cm2 (range 231–1400 cm2), and the mean diameter of resection was 28 cm (range 19–40 cm). In one patient, part of the lower lobe of the right lung was also resected.

Synthetic mesh was applied in 8 patients. In 9 patients, the chest wall was stabilized primarily with free rib grafts. Usually 1 or 2 ribs (eg, ribs number 6 and 8, or 5 and 7) from the affected side were harvested for grafts. The ribs, which were fixed to the bony chest wall with cerclage wires, were placed such that the bony defect was divided into smaller areas and the convex shape of the chest maintained. In recent years, we have also used a synthetic mesh tightened over and sutured to the rib grafts to give optimal stability and shape (Fig. 1b).

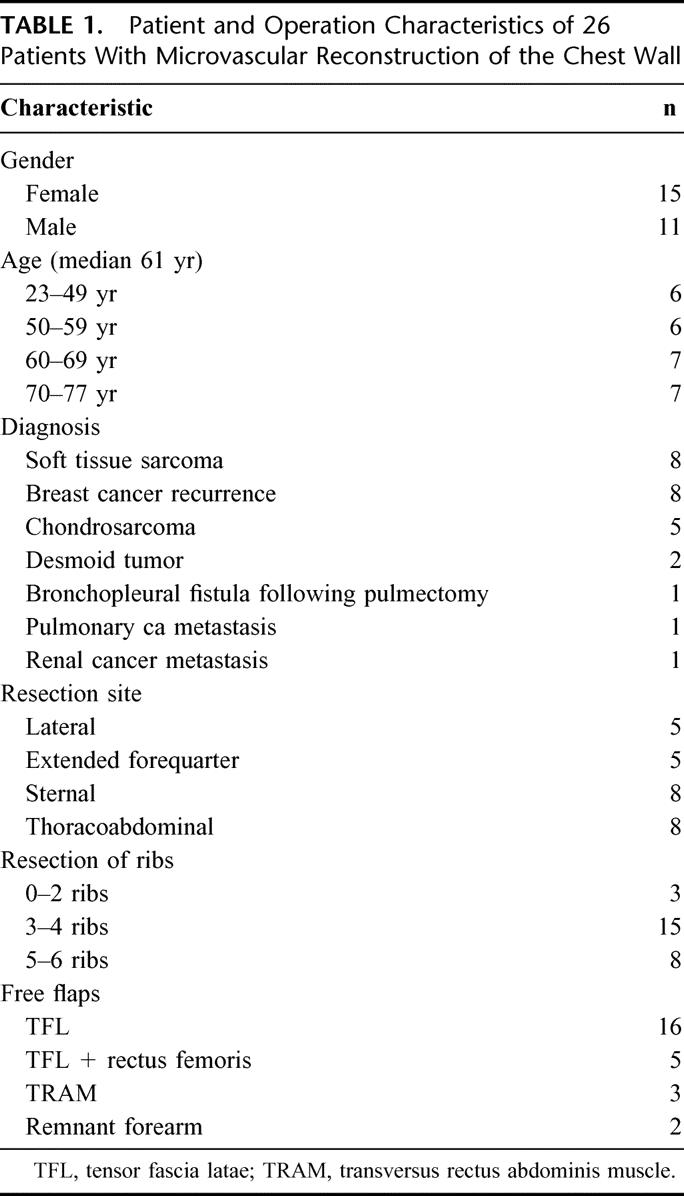

FIGURE 1. a: A 71-year-old woman with ulcerating local recurrence of breast cancer in the mastectomy scar invading into the chest wall. b: Full-thickness chest wall resection was performed, including the right half of the sternum and ribs. Stabilization was performed by free rib graft and synthetic mesh. c: Soft tissue was reconstructed with musculocutaneous transversus rectus abdominis free flap. d: The patient is disease free at 9 months.

Soft tissue coverage was attained in 21 patients with a tensor fasciae latae (TFL) flap (Fig. 2a–e). In 5 of these, the rectus femoris muscle was included to give greater reliability to the vascularity of the distal portion of the flap, to contribute extra muscle component to fill the chest cavity, or to provide wrapping around the corrected bronchopleural fistula site (Fig. 3a–c). In 3 patients, a transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous free flap was used (Fig. 1). Extended forequarter amputation was performed in 5 patients; in 2 of them the amputated extremity was not affected with malignancy and was used as a fillet forearm flap (Fig. 4a–c). The ulna was retained in the flap, osteotomized, and fixed with a plate to achieve stability and the convex shape of the chest wall. Additional stability was achieved in the other patient by splitting the radius and adding the pieces as bone grafts.

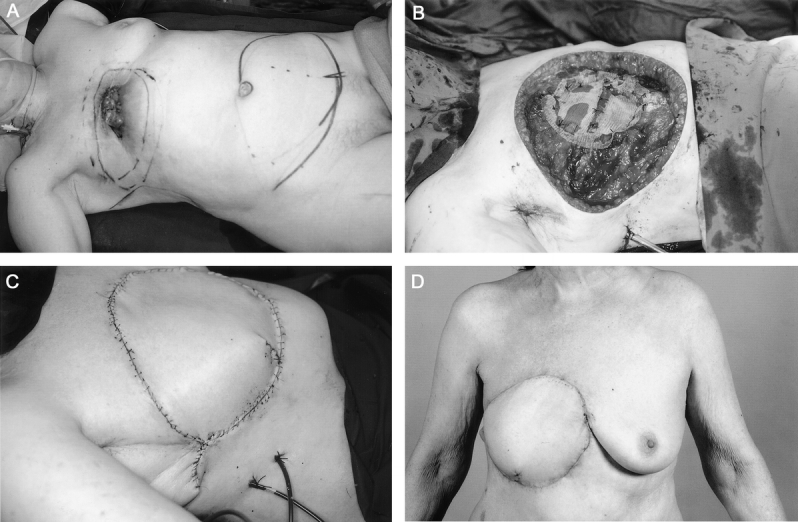

FIGURE 2. A 73-year-old man with primary malignant hemangiopericytoma in the lateral chest wall. Preoperatively chest x-ray (a) and CT scans (b) were taken. c: Full-thickness chest wall resection was performed with resection of six ribs. d: The chest wall was reconstructed with musculocutaneous tensor fasciae latae free flap. e: The patient is disease free at 6 years.

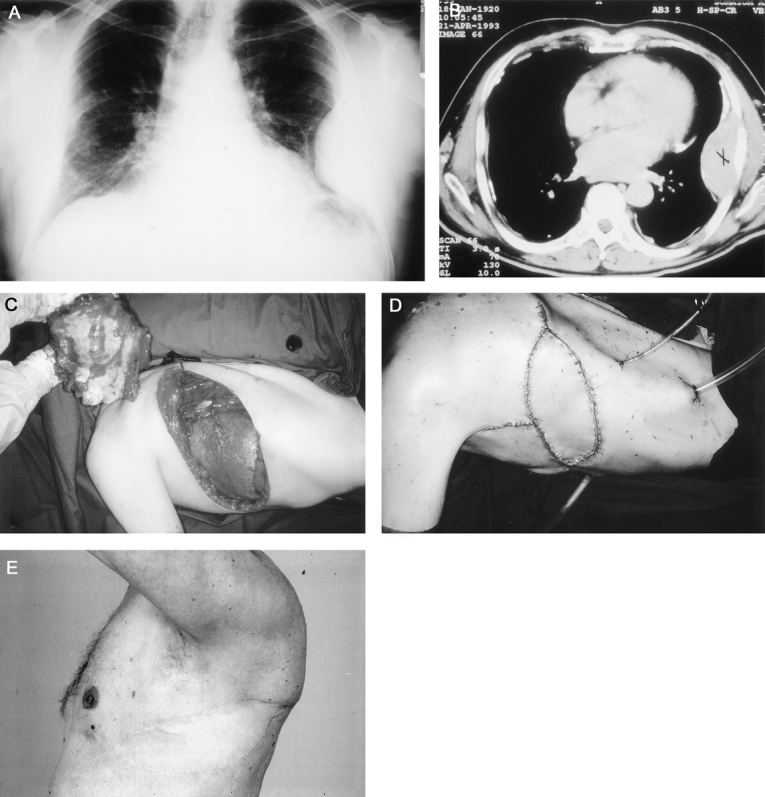

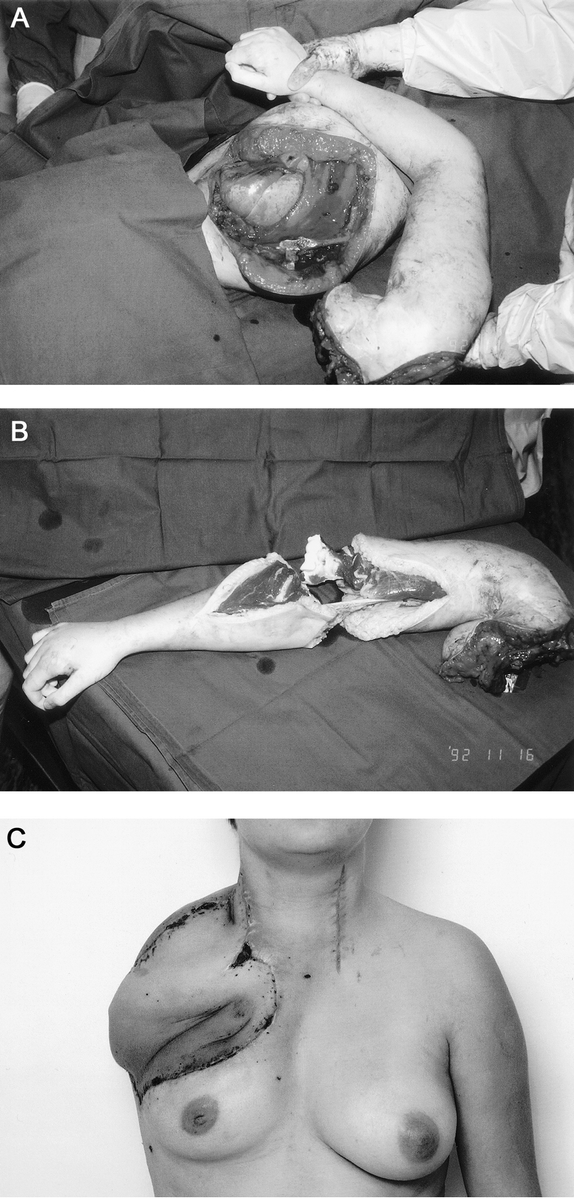

FIGURE 3. a: A 46-year-old woman with local recurrence of breast cancer and metastases adjacent to brachial plexus, vessels, and upper limb. The limb was painful, lymphoedematous, ulcerated, and paralyzed. b: Palliative forequarter amputation with chest wall resection was performed. c: The soft tissue defect was reconstructed with tensor fasciae latae (including rectus femoris muscle) free flap. The patient survived 2 years 5 months after the operation and evidently died of the disease.

FIGURE 4. A 23-year-old woman with local recurrence of high-grade soft tissue sarcoma invading brachial plexus. The right upper limb was paralyzed and extremely painful. a: Palliative forequarter amputation with resection of the chest wall was performed. b: The amputated forearm was dissected and used as osteomusculocutaneous free flap to cover the defect. c: The ulna was osteotomized and fixed to sternum to reconstruct the chest wall stability and shoulder contour. The patient died of the disease 8 months after the operation.

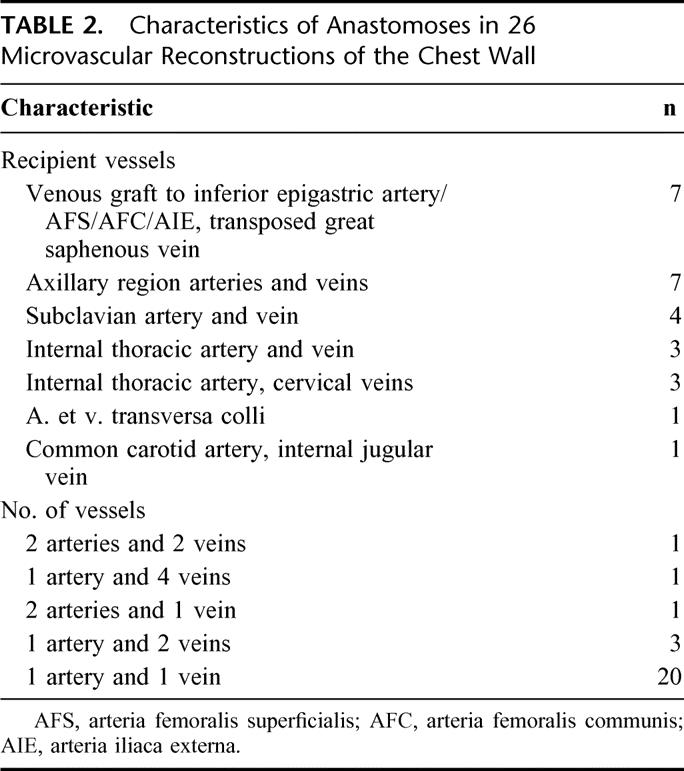

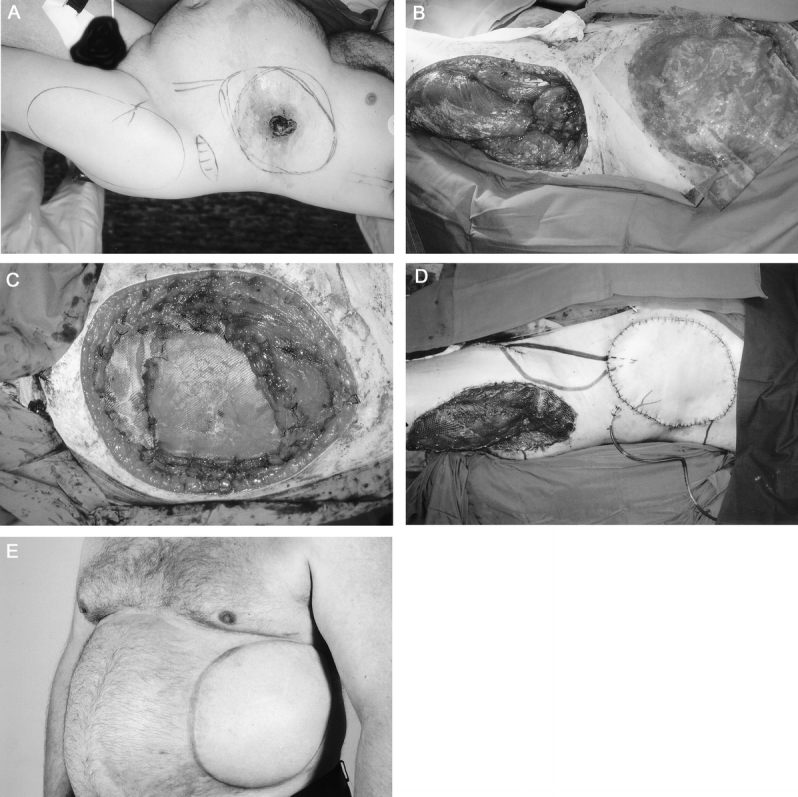

To reduce the operating time to a minimum, harvesting of the flap and resection (including preparation of the recipient vessels) were performed simultaneously. Once adequate recipient vessels had been found, the vascular supply to the flap was divided. Microvascular anastomoses were done in major vessels in axillary, subclavial, sternal, cervical, or inguinal areas either end-to-end or end-to-side (Table 2). The anastomoses were performed under magnifying operation glasses with 7–0 or 8–0 sutures. The vessels were flushed frequently with heparin-Ringer’s sterile solution. In 7 thoracoabdominal resections, the TFL flap had to be placed so proximally that the pedicle vessels could not reach the inguinal area (Fig. 5a–e). The great saphenous vein was dissected and divided above the knee, maintaining the proximal connection to the femoral vein. A loop was formed over the abdominal area, and the distal end of the vein was connected to the femoral, external iliac, or inferior epigastric artery.14–17 The loop was divided to provide the artery and the vein to the TFL free flap.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Anastomoses in 26 Microvascular Reconstructions of the Chest Wall

FIGURE 5. a: A 52-year-old man with ulcerating high-grade primary soft tissue sarcoma in the inferolateral chest wall. b: Resection of the chest and abdominal wall was performed and tensor fasciae latae free flap was raised. c: The defect was reconstructed with synthetic mesh (d) and tensor fascia latae free flap. Great saphenous vein was dissected, divided distally, and transposed 180 degrees proximally. A vascular loop was formed, and the distal end of the vein was anastomosed to superficial femoral artery. The loop was divided and pedicle vessels anastomosed. The course of the vessels is marked on the skin. e: The patient was disease free at 1 year. Evidently, the disease recurred and progressed fast, and the patient died 1 year 6 months after the operation.

Anticoagulation medication during and after the operation consisted of low molecular heparin 2500 IU administered subcutaneously twice a day. The medication was started on the first preoperative day and was discontinued when the patient was ambulatory, usually 7 to 12 days after the operation. Oral anticoagulation medication was not used.

RESULTS

Recovery

There was no perioperative mortality. The average operation time was 7 hours (range 3.5–10 hours) and perioperative blood loss was 3800 mL (range 700–7000 mL). The median treatment period in the intensive care unit was 6 days (range 0–35 days) and in the surgical ward 20 days (range 10–39 days). Four patients required a tracheostomy due to prolonged ventilatory support. Five patients needed further rehabilitation in other hospitals. All but 3 patients were able to return home after the operation.

Results of Microsurgery

No free flaps were lost. Revision of the microvascular anastomosis was required in 5 patients. Of these, 2 TFL patients had thrombosis in the pedicular vein, and the anastomoses were redone. In 1 patient with forequarter amputation and a remnant forearm flap, there was massive postoperative bleeding to the pleural cavity. In the reoperation, the pleura was reconstructed with free TFL transfer and the thrombosed pedicle vein was reanastomosed; this patient needed reanastomosis twice. Thrombosis in the pedicular artery occurred in 1 TFL patient owing to prolonged postoperative hypotension, and reanastomosis was performed. In 1 TFL patient, the arterial anastomosis ruptured and caused bleeding, and the anastomosis was redone.

Wound Healing

Three patients had healing problems in the resection site calling for operative treatment. Of these, 1 TFL patient and 1 transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous patient were operated on due to wound infection or breakdown. In these 2, revision and reconstruction were performed with a pedicled musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap, as we wanted to avoid any extra tension in the wound edges and ensure that the infected cavity was filled with well-vascularized muscle tissue. In 1 TFL patient, a small area of necrosis at the tip of the flap was excised and sutured in local anesthesia. There were no chronic deep infections or exposure of synthetic mesh or rib grafts.

Other Complications

One TFL patient with the anastomoses intra-abdominally in the iliac vessels developed an abdominal wall hernia, which was surgically treated. The flap donor site was revised in 3 TFL patients. One patient with forequarter amputation covered with plain TFL later needed a free rib graft owing to paradoxical movement of the chest wall that caused severe ventilatory dysfunction.

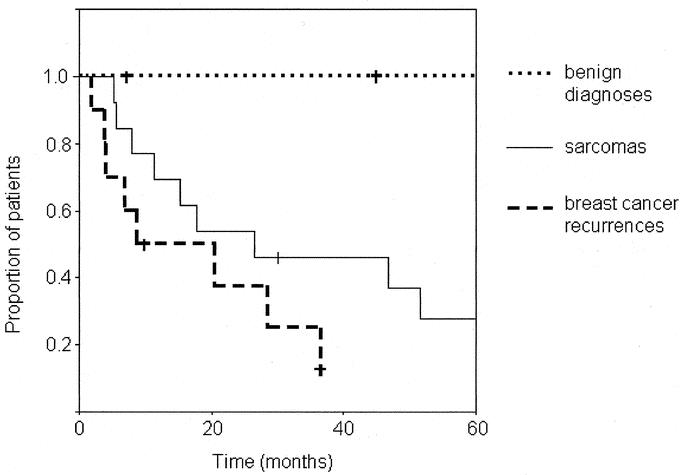

Survival

The overall survival rate in the whole group at 2 years was 52% and at 5 years 25%. During the follow-up period, 9 of 13 sarcoma patients and 8 of 10 breast cancer patients died of their disease. In the subgroup of sarcoma patients, the survival rate at 2 years was 54% and at 5 years 28%. In the subgroup of mammary cancer patients, the values were 38% and 13%, respectively. (Fig. 6) The mean survival time for patients with sarcomas was 39 months (median 27 months, range 5–83 months) and for those with breast cancer 18 months (median 9 months, range 2–37 months). In the subgroup treated with curative intention, the survival rate was 65% at 2 years and 38% at 5 years, with a mean survival time of 46 months (median 47 months, range 5–83 months). In the subgroup of patients treated palliatively, the values were 30% and 0%, respectively, with a mean survival time of 14 months (median 7 months, range 2–37 months).

FIGURE 6. Overall survival (Kaplan-Meier method) of 26 patients with full-thickness resections of the chest wall reconstructed with microvascular flaps.

DISCUSSION

Full-thickness chest wall resection with microsurgical reconstruction is one of the most challenging procedures in surgery today. Patients often present with advanced disease and compromised general condition, and their tolerance of complications is impaired. Careful individual evaluation is important; the risks and benefits must be carefully appraised. Even a minor problem may lead to major systemic complications, such as infection of the prosthetic material, mesh removal, or pulmonary dysfunction.

Because two extensive operations are combined, a two-team approach (tumor resection and free flap harvest) should be used to reduce the duration of these operations. If the defect affects only one pleural cavity, the intact side should not be needlessly disturbed by harvesting a latissimus dorsi flap with an extensive skin island, or rib graft. These procedures may hamper the patient’s respiratory function, thus prolonging, or even preventing, recovery. One large free flap harvested from a distant site may be safer than a combination of two pedicled flaps, which result in two donor sites with morbidity at or close to the chest area. Selection of the flap is important. The ideal flap has a constant anatomy, and a reliable and sufficiently large pedicle; its composition and size should be versatile and adequate for chest coverage; it should resist infection; and it should be possible to harvest it quite rapidly with the patient in either the supine or lateral position. Moreover, donor site morbidity should be acceptable and in proportion to the indication.

The TFL musculocutaneous flap can be very large (30–35 cm X 40–45 cm), and it can include the rectus femoris muscle if much muscle tissue is needed to cover a bronchopleural fistula or to fill the chest cavity after empyema. The pedicle is under the flap (not outside as in the latissimus dorsi flap), a location usually well suited to the anatomy of the defect. The TFL is especially suitable after forequarter amputation if the fillet extremity flap cannot be used. The pedicle is large and long, and it can be extended by taking the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. This maneuver is performed with very large flaps, and, if necessary, even one of the motor nerve branches to the vastus lateralis muscle may be divided (and reconstructed) to obtain optimal pedicle vessels. Clearly, the widest TFL donor sites cannot be closed primarily, and a skin graft cover must be used. Harvesting a TFL flap does not affect the patient’s respiratory function. The transverse rectus abdominis muscle makes a large, reliable, and constant flap. In suitable patients, donor site morbidity (pain, tension, and respiratory effect) is acceptable, but in very slim patients the flap will be of limited size. In addition, the effect on respiratory function may be considerable, especially in patients with advanced disease treated with several therapies and in a catabolic situation. If extended forequarter amputation is to be performed, the remnant lower arm (fillet forearm) is usually the first option for the free flap, assuming that the flap and the pedicle area (distal brachial vessels) are tumor free.

At the beginning, we did not use foreign materials or free rib grafts in our series because of our fear of deep infections. However, it became evident that stability is most crucial in the early postoperative period, when the patient is being extubated, and we began to use synthetic mesh and rib grafts more liberally. In our experience, bony stability is particularly important in patients who have a defect after sternal excision, high lateral resection, or extended forequarter amputation. Deep infection was not a problem in our patients, although the tumors were often infected, ulcerated, and irradiated. This may reflect the importance of well-vascularized flap tissue covering the defect, without the tension and vascular compromise often seen in pedicled flaps of limited size and range.

Perioperative mortality has been 0% to 17% in recent series of chest wall resections.4–6,18,19 Our results imply that extensive chest wall resections with microvascular reconstructions are relatively safe. Although long-term survival is poor, especially in breast cancer patients, the procedure may offer them remarkable palliation.2,20,21 Long-term survival is better in sarcoma patients, and in them the resections may even be curative.22 To achieve wide resection margins in local disease, microvascular reconstructions should perhaps be used more liberally in sarcoma patients.

Discussion

Dr. G.C. O’Sullivan: I am pleased to discuss this paper and I am grateful to ESA for the invitation and to the authors for sharing with me their manuscript. This is an important topic, and the authors are to be congratulated for their innovative approaches for they have shown that many patients can receive worthwhile palliation and, particularly in the case of sarcomas, may be cured. I suspect many of these patients across the Union are either undertreated or receive no treatment at all. Consequently, they are condemned to live through a protracted terminal phase of their illness in misery and despair with obviously progressing, painful, foul-smelling, and bleeding cancers.

These are a heterogeneous group of patients requiring individualized approaches with skillful and imaginative use of a diversity of surgical procedures.

The important issues are the type and stage of the cancer, the quality of the tissues available for reconstruction, stabilization of the thoracic wall, the function of the diaphragm, and the special problems with sternal resection.

My questions are: do you separate resection for palliation from resection for cure? Is further resection of ribs necessary for the reconstruction of the chest wall, particularly as a shield prosthesis of methylmethacrylate is so available and successful?

What were the specific problems that warranted tracheostomy and ventilation therapy in four patients?

I note 8 of your patients required thoracoabdominal resections: how did you reconstruct and preserve diaphragmatic function?

In the special circumstance of proximal sternal resection, do you have a policy of selection for palliation or cure. This is an area where major vessels and the phrenic nerves are particularly vulnerable during resection.

Let me finish by also complimenting you on your excellent presentation which, judging by the attentiveness of the audience, was so well received.

Dr. E. Tukiainen: Thank you for your insightful comments and questions.

We have used the cement technique as well, but not with this series of patients. The cement is sandwiched between two sheets of mesh and sutured into place. This technique can be used when a rib is not easily available. The result is quite stable, but there may be an increased risk of infection due to the large amount of foreign material. I agree that the cement technique could also have been used in some of the patients in this series. Sometimes, after anterolateral resection of several ribs, the remaining posterior part of one or two resected ribs can be harvested. This procedure reduces the size of the defect but also the chest volume, as does thoracoplasty. Sometimes, when a great amount of tissue is excised, a long rib graft can easily be harvested from the same exposure without causing additional morbidity.

The resected diaphragm must be sutured to its original position. If this cannot be done, the diaphragm has to be reconstructed with a Gore-Tex patch or synthetic mesh to pull it down. Otherwise, the function will not be adequate. The four patients requiring tracheostomy had pulmonary problems such as atelectasis or pulmonary infection. One of them was an elderly lady with an unstable chest wall after extended forequarter amputation. She could not manage without ventilatory support until a new operation to add rib grafts under the flap was performed. After this procedure, she no longer needed ventilatory support.

I agree that the proximal sternum is a dangerous area. It is usually resected only if the operation is expected to be curative. In my opinion, if the result seems to be palliative, the sternoclavicular area should be left intact. There is also a risk of injury to the phrenic nerve in this area.

Dr. M. Malago: Professor E. Tukiainen, recently I was surprised by a series from Miami where the abdominal wall was transplanted together with the intestine. I would be challenging you, since you would do this very complicated patchwork, to take the full-thickness composite skin allograft graft from a cadaveric donor and transplanting it to the patients you just described. Immunosuppression would be needed, and that can favor recurrence of tumors. Thus, my questions: regarding the patients with tumor recurrence, how did they fail: with local recurrence or with distant metastases?

And further to the operative strategy: would you entertain such a solution, cadaveric full-thickness grafts for primary soft tissue coverage, reserving the complicated patchwork you described for failures, or vice versa?

Dr. E. Tukiainen: Most of the patients have highly malignant tumors with a continuous risk of dissemination. Immunosuppressive medication would probably promote the spread of the disease and thus worsen the prognosis.

Dr. T. Lerut: I did enjoy this very impressive paper. Obviously, one of the key points here is stability of the chest wall and lung function correlating to that, but I have not seen anything on the lung function. Although for many patients this is palliation quality of life, and shortness of breath might be an important issue. I am just wondering if you take away some additional ribs from another side whether that is not just adding to the instability and impairing lung function afterward.

So do you have any data on the pulmonary quality of life and shortness of breath.

Dr. E. Tukiainen: This is an important question. Postoperative thoracic stability or lung function was not systematically measured in this series. In all but one patient, there was no clinically evident dyspnea, or then the degree of dyspnea was so mild that further operational interventions would not have been reasonable. Thus, lung function tests were not performed. I agree that preoperative and postoperative respiratory function tests would have been of scientific interest.

The rib grafts are always harvested from the side of the resection, if not sternal, to avoid morbidity in the healthy side. We prefer inferior ribs as grafts (nos. VIII-XI). At least one intact rib is always left between the chest wall defect and the donor site, and preferably no adjacent ribs are harvested. In an elderly person, even a conventional fibular graft can be harvested and used as a long bone graft for stabilization to minimize morbidity in the chest area.

In our experience, immediate postoperative stability is the most important factor determining the recovery of the patient.

Footnotes

Reprints: Erkki Tukiainen, MD, PhD, Department of Plastic Surgery, Helsinki University Hospital, P.O. Box 266, 00029 HUS, Finland. E-mail:erkki.tukiainen@hus.fi.

REFERENCES

- 1.Incarbone M, Pastorino U. Surgical treatment of chest wall tumors. World J Surg. 2001;25:218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandeweyer E, Nogaret JM, Hertens D, et al. Chest coverage and reconstruction after recurrence of breast cancer. Eur J Plast Surg. 2002;25:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapelier AR, Bacha EA, de Montpreville VT, et al. Radical resection of radiation-induced sarcoma of the chest wall: report of 15 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordeiro PG, Santamaria E, Hidalgo D. The role of microsurgery in reconstruction of oncologic chest wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1924–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold PG, Pairolero PC. Chest-wall reconstruction: an account of 500 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansour KA, Thourani VH, Losken A, et al. Chest wall resections and reconstruction: a 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1720–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathes SJ. Chest wall reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1995;22:187–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuels L, Granick MS, Ramasastry S, et al. Reconstruction of radiation-induced chest wall lesions. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;31:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nash AG, Tuson JRD, Andrews SM, et al. Chest wall reconstruction after resection of recurrent breast tumours. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiba E, Koyama H, Noguchi S, et al. Reconstruction of the chest wall after full-thickness resection: a comparison between myocutaneous flap and acrylic resin plate as reconstructive techniques. Int Surg. 1988;73:102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson BO, Burt ME. Chest wall neoplasms and their management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:1774–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroll SS, Walsh G, Ryan B, et al. Risks and benefits of using Marlex mesh in chest wall reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;31:303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabanathan S, Shah R, Mearns JA. Surgical treatment of primary malignant chest wall tumours. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman AM, Meland NB. Arteriovenous shunts in free vascularized tissue transfer for extremity reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earle AS, Feng LJ, Jordan RB. Long saphenous vein grafts as an aid to microsurgical reconstruction of the trunk. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1990;6:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KA, Chandrasekhar BS. Cephalic vein in salvage microsurgical reconstruction in the head and neck. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karanas YL, Yim KK, Johannet P, et al. Use of 20 cm or longer interposition vein grafts in free flap reconstruction of the trunk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Kattan KM, Breach NM, Kaplan DK, et al. Soft tissue reconstruction in thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1372–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen M, Ramasastry SS. Reconstruction of complex chest wall defects. Am J Surg. 1996;172:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downey RJ, Rusch V, Hsu FI, et al. Chest wall resection for locally recurrent breast cancer: is it worthwhile? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlstrom KK, Andersson AP, Andersen M, et al. Wide local excision of recurrent breast cancer in the thoracic wall. Cancer. 1993;72:774–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh GL, Davis BM, Swisher SG, et al. A single-institutional, multidisciplinary approach to primary sarcomas involving the chest wall requiring full-thickness resections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]