Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether patient and graft survival following transplantation with non-heart-beating donor (NHBD) hepatic allografts is equivalent to heart-beating-donor (HBD) allografts.

Summary Background Data:

With the growing disparity between the number of patients awaiting liver transplantation and a limited supply of cadaveric organs, there is renewed interest in the use of hepatic allografts from NHBDs. Limited outcome data addressing this issue exist.

Methods:

Retrospective evaluation of graft and patient survival among adult recipients of NHBD hepatic allografts compared with recipients of HBD livers between 1993 and 2001 using the United Network of Organ Sharing database.

Results:

NHBD (N = 144) graft survival was significantly shorter than HBD grafts (N = 26,856). One- and 3-year graft survival was 70.2% and 63.3% for NHBD recipients versus 80.4% and 72.1% (P = 0.003 and P = 0.012) for HBD recipients. Recipients of an NHBD graft had a greater incidence of primary nonfunction (11.8 vs. 6.4%, P = 0.008) and retransplantation (13.9% vs. 8.3%, P = 0.04) compared with HBD recipients. Prolonged cold ischemic time and recipient life support were predictors of early graft failure among recipients of NHBD livers. Although differences in patient survival following NHBD versus HBD transplant did not meet statistical significance, a strong trend was evident that likely has relevant clinical implications.

Conclusions:

Graft and patient survival is inferior among recipients of NHBD livers. NHBD donors remain an important source of hepatic grafts; however, judicious use is warranted, including minimization of cold ischemia and use in stable recipients.

Non-heart-beating donors have been cited as a means to increase the supply of hepatic allografts, although little outcome data exist. Graft and patient survival were determined from an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Graft survival was found to be inferior.

The growing disparity between the number of patients awaiting liver transplantation and a limited supply of cadaveric organs has increased waiting times and, consequently, the number of wait list deaths.1 Several methods are available to narrow this gap, including split liver and living donor liver transplantation. Another potential method to increase the supply of organs is the use marginal donors, in particular the use of non-heart-beating donors (NHBDs). These donors are usually individuals with devastating irreversible neurologic injuries but who do not meet formal brain death criteria. Therefore, death is based upon cessation of cardiopulmonary function. Patient and graft survival following liver transplantation with NHBD grafts is not well defined.

NHBDs may be classified as controlled or uncontrolled. Controlled donors are hemodynamically stable individuals who are extubated in the operating room or intensive care unit following a decision by the patient’s next of kin to withdraw care and provide consent for organ donation. This is a planned event in which the donor surgical team is present to recover the organs rapidly, therefore limiting warm ischemic time. Uncontrolled donors, as the name implies, are individuals in whom cessation of cardiopulmonary function is an unplanned event. This group consists of individuals who sustain cessation of cardiopulmonary function prior to arriving to a hospital, within the emergency department, or as hospital inpatients. Brain dead donors who sustain cardiopulmonary arrest in the intensive care unit or on the way to the operating room prior to organ donation are also considered uncontrolled NHBDs.2 There may be substantial warm ischemia incurred between the time of the donor’s death and perfusion of the organs during procurement with cold preservation solution.

Uncontrolled donors represent the largest pool of potential organ donors and by some estimates could add at least an additional 5000 donors per year.3,4 However, significant ethical, legal, and logistical issues will likely preclude the use of uncontrolled donors to any significant extent in the United States. Controlled NHBDs face few of these problems and have the potential to add about 1000 additional donors per year.4–6 This group is currently underutilized and represents a potential source for a variety of solid organs.

The procurement of organs from NHBDs is not a new concept. Prior to the publication of the Harvard neurologic definitions and criteria for death in 1968 and subsequent passage of brain death laws, most retrieved organs were from NHBDs. With acceptance of brain death, issues related to donor warm ischemic time were eliminated. The growing shortage of organs has rekindled interest in the use of NHBDs. Several reports demonstrate that kidneys obtained from controlled NHBDs have similar outcomes as those obtained from heart-beating-donors (HBDs).7–9 However, the renewed interest in hepatic allografts from NHBDs has been approached with trepidation as the liver may be less tolerant of donor warm ischemic time. Several individual centers have published limited and disparate experiences.10–12 The purpose of the present study is to assess patient and graft survival among a large cohort of recipients of hepatic allografts from NHBDs.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis using data from the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. From the initial dataset provided by UNOS, which consisted of all hepatic transplants performed between April 1987 and December 6, 2001, the study population was limited to adults 18 years or older receiving a primary hepatic allograft; 1993 was selected as the starting point as this was the first year that NHBD status was identified in the UNOS database. Those patients who received a partial hepatic allograft, had a history of a previous transplant, or with the exception of a kidney received a simultaneous transplant, were excluded from the analysis. Patients without follow-up were also removed from the analysis. Subsequent to all exclusions, 27,000 patients remained available for analysis, and of these 144 were recipients of an NHBD hepatic allograft.

Primary endpoints were graft failure and patient death. Graft survival was defined as time from initial transplant to graft loss, patient death, or last follow-up. Patient survival was considered from time of first transplant to patient death or last known follow-up. Primary nonfunction was defined as graft failure within 7 days of transplantation.

Potential confounding donor and recipient variables were examined. Donor factors included age, sex, race, and use of pressors prior to organ procurement. Recipient characteristics at the time of transplantation included age, sex, race, dialysis, preoperative total bilirubin, prothrombin time, albumin, creatinine, use of life support (defined as use of pressors, mechanical ventilation, or “life support” as categorized in the UNOS database), and recipient medical status prior to transplantation (home, in the hospital, or in the intensive care unit). Medical status served as a surrogate for UNOS status that had undergone a number of modifications during the time period included in this study. Other variables included donor warm ischemic time, recipient warm ischemic time, cold ischemic time, and year of transplant.

Prior to analysis the database was examined for implausible data.13 Outlying data were excluded. Ranges considered plausible were defined as: cold ischemic time (1–20 hours), recipient warm ischemic time (1–90 minutes), albumin (0.7–6.0 g/dL), total bilirubin (0.1–70 mg/dL), prothrombin time (9–90 seconds), creatinine (0.1–15.0 mg/dL), and donor age (<100 years). A total of 3820 patients were not assigned to a non-heart-beating status and were assumed to have received an HBD graft.

χ2 analysis and Student t tests were used for comparison of proportions and means between NHBD and HBD groups. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to compute overall patient and graft survival. Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival between groups was performed using the log-rank statistic. Cox proportional-hazards analysis was used to identify factors independently associated with patient and allograft survival. Each potentially confounding variable was individually examined in a model containing only NHBD and that variable. If the variable resulted in an adjusted hazard ratio that differed from the crude hazard ratio for the association of NHBD and survival by ±10%, then that variable was included in the final model. A method of imputation based on all other available variables was used to assign values to missing confounding variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Graduate Pack 11.0 for Windows (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Utilization of Hepatic Allografts From NHBDs

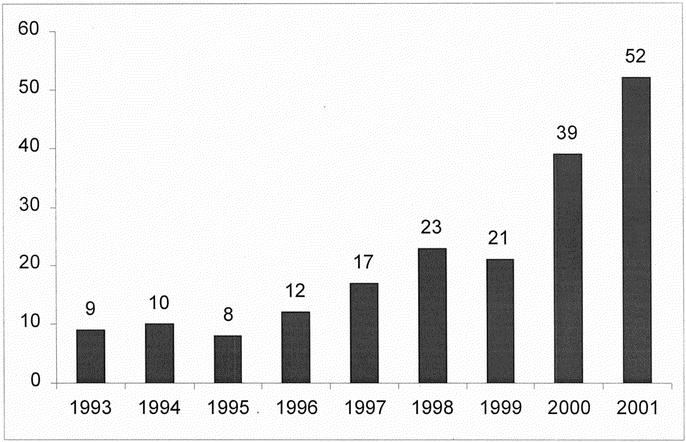

The dataset from UNOS identified 191 transplants with NHBD hepatic allografts between 1993 and 2001. The use of NHBD hepatic allografts has increased steadily (Fig. 1) since 1993. In 1993, NHBD hepatic allografts represented 0.26% of all hepatic transplants performed in the United States. By 2001, this had increased to 1.1%.

FIGURE 1. Number of liver transplants from NHBDs performed per year.

Donor and Recipient Characteristics

NHBDs and HBDs differed in several respects (Table 1 and 2). NHBDs had shorter cold ischemic times and were less likely to require pressor support compared with HBDs. NHBD recipients were more likely to have a history of malignancy and were older than HBD recipients, although the latter did not reach statistical significance. There was a trend toward shorter waiting times among recipients of an NHBD graft.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Allograft Donors

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Allograft Recipients

Outcome Following NHBD Versus HBD Liver Transplantation

Following transplantation, length of stay did not differ between the two groups; however, the number of patients with primary nonfunction or those who required retransplantation was greater among the NHBD recipients (Table 2).

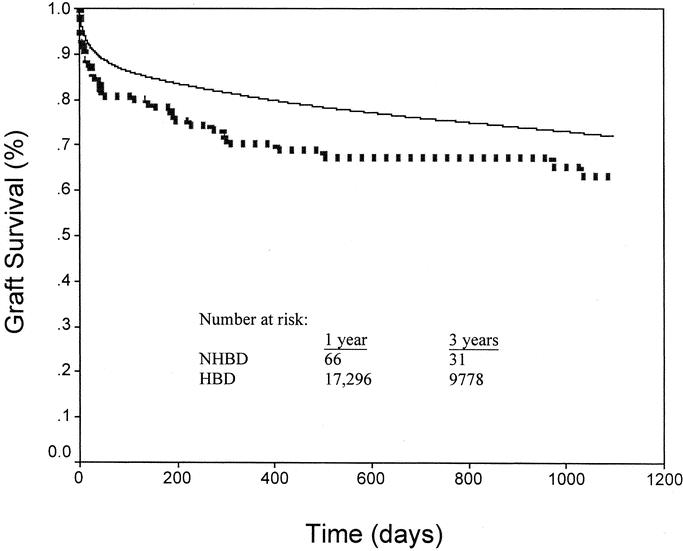

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, graft survival was found to be significantly shorter among NHBD grafts when compared with HBD grafts. One- and 3-year survival was 70.2% and 63.3% for NHBD recipients versus 80.4% and 72.1% (P = 0.003 and P = 0.012) for HBD recipients (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Kaplan-Meier graft survival for NHBDs and HBDs. NHBD graft survival (dotted line) was significantly less than HBD survival (solid line) at 1 (70.2 vs. 80.4%, P = 0.003) and 3 years (63.3 vs. 72.1%, P = 0.012).

Univariate analysis of HBD recipient compared with NHBD recipient status produced a hazard ratio of 0.696 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.52–0.94, P = 0.018). None of the covariates, when tested individually with NHBD status, resulted in a significant change to the NHBD hazard ratio. Subsequently, a multivariable analysis was performed to ensure that adjusting simultaneously for multiple covariates would not change the result. This analysis revealed an NHBD hazard ratio of 0.688 (95% CI = 0.43–1.1, P = 0.116) among 11,836 patients with complete data. The change in hazard ratios from 0.696 to 0.688 is likely due to the loss of patients with incomplete data and was considered insignificant. A multivariate analysis on all 27,000 patients using imputation methods to substitute for missing values within the covariates was performed. The hazard ratio for HBD recipients was 0.651 (95% CI = 0.48–0.88, P < 0.005), substantiating our univariate value of 0.696.

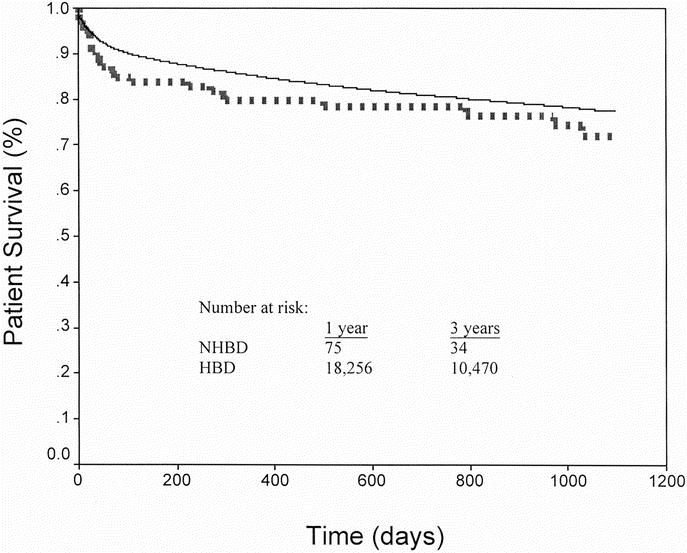

Patient survival by the Kaplan-Meier method was not significantly different between recipients of an NHBD and HBD graft (Fig. 3); however, there was a strong trend that patient survival was inferior, especially at the 1-year time point. Among NHBD recipients, 1- and 3-year patient survival was 79.7% and 72.1%, respectively. For HBD recipients, 1- and 3-year survival was 85.0% and 77.4% (P = 0.082 and 0.146, respectively).

FIGURE 3. Kaplan-Meier patient survival for NHBDs and HBDs. NHBD patient survival (dotted line) was similar to HBD (solid line) at 1 (79.7 vs. 85.0%, P = 0.082) and 3 years (72.1 vs. 77.4%, P = 0.146).

Analysis of Early Graft Failure

Factors influencing NHBD graft failure within the first 60 days following transplantation were investigated because much of the difference between NHBD and HBD graft survival occurred within this time; 18.1% (N = 26) of NHBD versus 11.7% (N = 3137) of HBD grafts failed within the first 60 days following transplantation (P = 0.02), whereas NHBD and HBD grafts that survived more than 60 days had similar 1- and 3-year survivals (86.9% vs. 91.3%, P = 0.21; and 78.4% vs. 81.9% P = 0.421).

Differences between NHBD grafts that failed or survived within the first 60 days were examined by Cox regression analysis. Covariates that individually influenced NHBD graft failure within the first 60 days following transplantation included life support at time of transplantation (hazard ratio [HR] = 5.13, 95% CI = 2.2–12.2, P < 0.001), dialysis at the time of transplantation (HR = 5.25, 95% CI = 1.2–22.6, P = 0.026), preoperative prothrombin time (per second change, HR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.01–1.2, P = 0.024), and cold ischemic time (per hour change, HR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.05–1.33, P = 0.007). However, only cold ischemic time remained significant in a multivariate analysis (HR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.00–1.36, P = 0.047). Among NHBD grafts that failed within the first 60 days, mean cold ischemic time was 9.4 ± 3.38 hours, whereas cold ischemic time was 7.76 ± 2.6 hours for those that did not fail. To compensate for the loss of patients with incomplete data, multivariate analysis using imputed data demonstrated that life support (HR = 3.14, 95% CI = 1.13–8.71, P = 0.028) in addition to cold ischemic time were significant factors in graft outcome.

Allografts From Controlled Versus Uncontrolled Donors

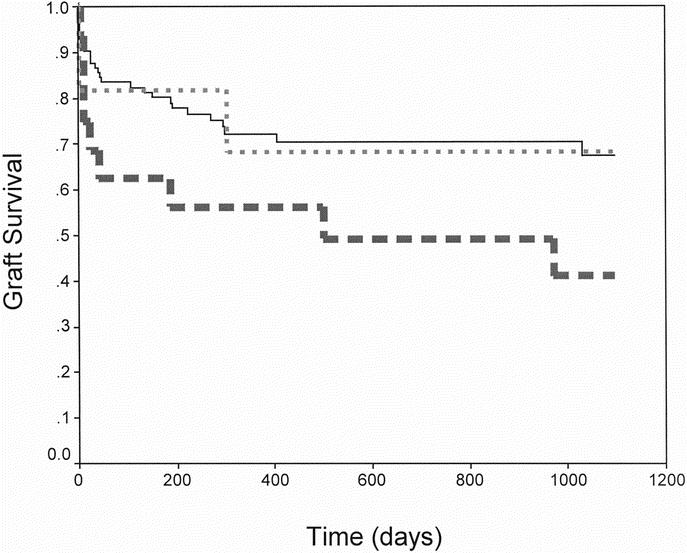

Of the 144 NHBD grafts, the UNOS database characterized 117 as controlled, 11 as uncontrolled, and 16 were unknown or not identified (Fig. 4). Grafts from controlled and uncontrolled donors had similar survival, whereas the unidentified group had a poorer survival (1 year 72.3%, 68.2%, and 56.3%, respectively). When recipients of a controlled NHBD graft were compared with recipients of an HBD liver, the difference in graft survival at 1 year approached significance (72.3% vs. 80.4%, P = 0.056); however, this did not persist at 3 years (67.8% vs. 72.1%, P = 0.15).

FIGURE 4. Kaplan-Meier NHBD graft survival for controlled donors (N = 117, solid line), uncontrolled donors (N = 11, small dashes), and unidentified patients (N = 16, large dashes).

DISCUSSION

NHBDs have been cited as a means to ameliorate the growing demand for transplantation. Despite calls for the use of hepatic grafts from NHBDs, there are few studies examining long-term outcomes and predictors of graft failure. The present analysis attempts to address these issues by examining nationally representative data. Recipients of an NHBD graft were found to have a 30% increase in the risk of graft failure when compared with recipients of an HBD liver. This finding persisted even after adjustment for multiple recipient, donor, and center specific variables. The increased risk of graft loss is reflected by a higher incidence of primary nonfunction and retransplantation among NHBD recipients. The inferior graft survival is also reflected in a strong trend toward poorer patient survival in those receiving NHBD grafts. Although statistical significance was not met in the patient survival analysis, this is likely due to power limitations in the study. The trend toward inferior patient survival, and the increased rate of retransplantation in recipients of NHBD livers, is also undoubtedly a marker for higher rate of patient morbidity in this subset of transplants that is not evident in the UNOS database.

The differences in NHBD and HBD graft survival appeared within the first 60 days following transplantation and persisted to a similar extent during the duration of follow-up. Cold ischemic time was the factor most significantly associated with poor outcome. Every additional hour of cold ischemic time increased the risk of graft failure by 17%. Among NHBD grafts with a cold ischemic time greater than 8 hours, the incidence of graft failure within 60 days of transplantation was 30.4% and increased to 58.3% (7 of 12 grafts) when cold ischemic time exceeded 12 hours. Conversely, when cold ischemic time was less than 8 hours, only 10.8% of NHBD grafts failed within 60 days.

Although life support predicted 60-day graft failure in a univariate analysis, it failed to remain significant in a multivariate analysis. The lack of significance is likely related to inadequate statistical power due to the loss of patients with incomplete data. When a multivariate analysis was performed using imputation methods, life support remained a significant predictor of graft loss within the first 60 days. Among patients receiving life support at the time of transplantation, 27% experienced graft failure within 60 days as compared with 4.2% not on life support. That other factors such as donor age and donor warm ischemic time were not significant in predicting early graft outcome might be attributed to the notion that the NHBD hepatic allografts came from a highly selected donor population. Mean NHBD donor age was only 35.5 years and graft failure was not found to increase until donor age was more than 60 years. Of the 12 grafts from donors older than 60 years, graft failure at 60 days was 25%.

Three single center studies from the United States have examined the outcome of NHBD hepatic allografts. Our results paralleled those of D’Alessandro et al, who noted inferior allograft survival, but not inferior patient survival among recipients of livers from NHBDs; NHBD recipients experienced a higher incidence of primary nonfunction than HBD recipients.10 The University of Pittsburgh reported a 50% 1-year patient and graft survival with 6 NHBD livers. One third of these patients developed hepatic artery thrombosis within 1 month of transplantation.11 Reich et al have reported a 100% patient and graft survival at a mean follow-up of 18 months in 8 patients.12 These single center studies provide insight into specific complications, variations in procurement technique, and causes of graft failure and patient death that are unavailable or incompletely documented in the UNOS database.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of this study is the inability to adequately analyze precisely the outcome among controlled and uncontrolled NHBDs. The small number of patients identified as uncontrolled donors had similar graft survival as those grafts derived from controlled donors. However, because of the large number of unassigned patients that had an inferior outcome, we were reluctant to assign them to either the controlled or uncontrolled group. While it may be tempting to draw conclusions about the use of uncontrolled donors from these results, the number of patients is limited. Graft survival from the 117 identified recipients of a controlled donor graft was inferior to recipients of a HBD liver at 1 year but not at 3 years. Casavilla et al11 have reported 6 hepatic transplants from uncontrolled donors. Three of the grafts failed within the first week following transplant. One-year actuarial patient and graft survival were 67% and 17%, respectively.11Gomez et al from Spain have reported results using 8 livers from uncontrolled donors. Three patients were retransplanted within the first month, two for primary nonfunction and one due to hepatic artery thrombosis. With a mean follow-up of 8.5 months, only one patient had died.14

While this report demonstrates inferior graft survival using NHBDs, the question remains whether hepatic allografts from NHBDs should continue to be used. Based on this analysis and the continued shortage of hepatic allografts in the foreseeable future, we recommend the use of these organs, however, with several caveats. Donors should be younger than 60 years and donor warm ischemic time needs to be minimal, preferably less than 30 minutes. Recipient selection is essential as early graft loss is considerable if the recipient is intubated or on pressors. Most importantly, cold ischemic time needs to be minimized, and if at all possible, kept to less than 8 hours. This would suggest that hepatic allografts from NHBDs be used within a local organ procurement organization to minimize cold ischemia. Justification for the use of allografts from NHBDs may be defended by similar long-term patient survival to HBD recipients.

This study has demonstrated inferior graft survival for NHBD liver grafts. By limiting cold ischemic time and by using the grafts in medically fit recipients, better outcomes are possible. The number of hepatic allografts performed from NHBDs is relatively small and will require reevaluation in several years as more centers gain experience with these grafts.

Footnotes

Reprints: James F. Markmann, MD, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Surgery, 4 Silverstein, 3400 Spruce St., Philadelphia, PA 19104. E-mail: James.Markmann@uphs.upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 2000 Annual Report. February 16, 2001.

- 2.Kootstra GG, Daemen JH, Oomen AP. Categories of non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2893–2894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kootstra G, Arnold RM, Bos MA, et al. Round table discussion on non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2935–2939. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herdman R, Potts JT. Non-Heart-Beating Organ Transplantation: Medical and Ethical Issues in Procurement. Institute of Medicine, 1997. [PubMed]

- 5.Koogler T, Costarino AT. The potential benefits of the pediatric nonheartbeating donor. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1049–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan HM, Jarrell BE, Broznik B, et al. Estimation and characterization of the potential renal organ donor pool in Pennsylvania. Transplantation. 1991;51:142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho YW, Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, et al. Transplantation of kidneys from donors whose hearts have stopped beating. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orloff MS, Reed AI, Erturk E, et al. Non-heart-beating cadaveric organ donation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Alessandro AM, Hoffmann RM, Belzer FO. Non-heart-beating donors: one response to the organ shortage. Transplant Rev. 1995;9:168–176. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Alessandro AM, Hoffmann RM, Knechtle SJ, et al. Liver transplantation from controlled non-heart-beating donors. Surgery. 2000;128:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casavilla A, Ramirez C, Shapiro R, et al. Experience with liver and kidney allografts from non-heart-beating donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reich DJ, Munoz SJ, Rothstein KD, et al. Controlled non-heart-beating donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;70:1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman LM, Lewis JD, Berlin JA, et al. The association between hepatitis C infection and survival after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2002;122:889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez M, Garcia-Buitron JM, Fernandez-Garcia A, et al. Liver transplantation with organs from non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:3478–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]