The purpose of this brief essay is first to outline and then to examine critically the basic philosophical and practical tenets which, in my personal view, represent the fundamental props supporting the conceptualization of the meaning and value of the ABS basic certificate in Surgery. The term “basic certificate” refers to the initial certificate offered to candidates by the Board, often called colloquially the “General Surgery Certificate” to distinguish it from the advanced specialty certificates also awarded by the Board. Three decades ago, the questions posed in the title would rarely have been asked. The basic certificate had cache and patina simply because it was enough for the public and the profession to know that a candidate had to meet a broad array of rigorous requirements to obtain it. These included successful completion of a General Surgery residency program and a stringent two-part examination process designed to assess essential cognitive knowledge in the discipline and to evaluate the ability to reason through a wide range of relevant clinical problems to a successful conclusion.

It is increasingly apparent to me, however, that these criteria in and of themselves may no longer be sufficiently robust. Given that assessment, my motive for undertaking this task is straightforward: I am convinced that the processes of certification in Surgery have meaning, value, and relevance largely in proportion to the degree that the basic certificate possesses these same qualities in a credible way. That certificate is currently under siege, I believe, because of the considerable anxieties being experienced in the academic surgical community concerning the future of the surgical workforce, with particular focus on the manner in which it should be educated to best serve the public good. Those anxieties are real; they reflect the many vexing problems facing that community, including altered candidate demography, decreasing candidate numbers, changing candidate expectations about lifestyle, perceived declines in candidate quality, and mandated reductions in actual training time, among many others. In such an uncertain and volatile environment, history teaches us that no concept is inviolate; no construct is indispensable; and reform, often precipitous, is the order of the day. These are all very appropriate responses, but I fear that, in the rush to change, those aspects of the current educational paradigm that have real value, including those elements of basic certification that I view as central to the integrity of ABS, are at risk for being discarded because their value is not adequately appreciated.

The frequency with which respected colleagues question that value is clear evidence of the trend. Among other things, it has been charged that the broadly trained and relatively versatile surgeon, which the certificate purports to identify, is a fiction; that, in any case, there is no role for such individuals in today's surgical world; that it takes too long to create these generalists to the detriment of specialists and specialist care; and that, as a consequence of all of this, the basic certificate has minimal currency today and that its most appropriate fate is to be cannibalized.1,2,3

Let me try to respond to these assertions by reviewing briefly the evolution of the Board movement in North America, by outlining the stated purposes and organization of the ABS, by detailing the basic principles that I perceive underlie ABS decision-making concerning certification and its meaning, and by commenting on certain trends in surgical education and practice that are very likely to impact, some positively and some negatively, on the meaning of the basic certificate. The views being expressed are in no way official; rather, they are my own based on a more than 20-year association with the activities of the ABS, including 9 eventful years as its Executive Director. The essence of the message is that, in my opinion, basic certification by the ABS continues to have relevance to the modern surgical circumstance.

Growth of the Modern Board Movement

It is useful to review briefly the development of the Board movement in North America, because there are lessons to be learned from that story that bear directly on some of the problems of the present. The most important of these is that the concept of certification did not spring fully developed from the deliberations of some sagacious group of all-knowing elders. Rather, like most entities of the kind, it evolved gradually over time, in patterns of fits and starts, often haphazard, and occasionally even irrational. Initially, there existed little uniformity of approach, organization, or process, and no universally agreed upon philosophical construct concerning the meaning of certification. Because these failings have not yet been fully dealt with even today, they have lived on to color and influence some of the events of the present. Lesson of history number one.

The Board movement in North America came into being as one manifestation of the great reformist thrust in medical education that occurred in the early years of the 20th century (eg, the Flexner Report of 1906). The concept was first proposed by the President of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology who, in 1908, urged the Academy to develop a mechanism for identifying to the public true specialists in ophthalmologic disease: those who distinguished themselves from large numbers of poorly qualified practitioners, and who did so by virtue of extensive training and experience and by having successfully completed a stringent examination process overseen by acknowledged experts in the discipline. It required 9 years of gestation before this proposal was implemented (1917), undoubtedly because of the less-than-enthusiastic but very human response of those in the Academy who felt they might be at risk from this kind of schema. In fact, only 3 new Boards were established over the next 15 years and, as noted, by processes which were quite nonuniform. That circumstance was not remedied by the establishment in 1933 of the Advisory Board for Medical Specialties because it was precisely as its title indicated—advisory only. As a consequence, the rush to create new Boards in the decades of the 1930s and 1940s was as eclectic as it had been previously, a state of affairs largely (but not completely) corrected by the creation of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in 1970. Nevertheless, the ABMS is an important quality control device for all of graduate medical education today.

The ABS was established in 1937 as a direct result of Edward Archibald's 1935 Presidential Address to the American Surgical Association, urging the creation of a system of accreditation of surgeons, separate from membership in the American College of Surgeons,4 the standards for which were in his view too low. “Our guild,” he said, “has its masters and we must see to it that our apprentices by instruction and through examination become masters as well.” This charge was eagerly embraced by Evarts Graham and other young turks, so that, within 2 years, the ABS was incorporated, organized, and functioning. It is noteworthy, however, that ABS was the 11th Board to be established and that all but one of the other surgical Boards had already been incorporated or were in the process of incorporating before ABS was in place. Herein is lesson of history number two: even if ABS had been wise enough to see the advantages, no possibility ever existed for it to serve as an anchor and centerpiece for a broad federation of surgical specialties designed to serve common needs and to achieve common goals in a common and collegial and organized way.

The establishment of the ABMS, which now comprises 24 Member Boards, coincided with and likely fostered a new phenomenon in the Board movement: the creation of specialty certificates: 14 between 1970 and 1980, an additional 24 between 1980 and 1990, and 36 more between 1990 and 2000, for a grand total of 74 at present. Lesson of history number three: while some nonsurgical Boards have never met a specialty certificate they didn't like, the surgical Boards have been very stingy in this regard, having endorsed only 10 such certificates in 30 years. This stance is undoubtedly a consequence of the recognition that, while specialty certificates are clearly valuable because they demonstrably promote the legitimate and salutary growth of specialty medicine, they can also be dangerous to the extent that they create a mindset in some of franchising and exclusion, to the detriment of the broader basic discipline and the public which it serves. My personal view is that they may be inevitable, however. That being the case, the challenge is to keep the process healthy by ensuring that it reflects true specialty development but not fragmentation—no easy task.

Purposes and Organization of the Board

The ABS was incorporated as a private, voluntary, nonprofit organization with 3 stated purposes in mind: first, to conduct examinations of appropriately qualified candidates; second, to issue certificates to those who complete the examination process successfully; and, third, to set standards and to broaden and improve the opportunities available for the graduate education and training of surgeons. This last is the most important because it places within the legitimate interests of the ABS the entire spectrum of activities and initiatives associated with graduate medical education (GME) in surgery and of post-GME as well.

These purposes are overseen by the more than 30 Directors of the Board who are elected from 25 different nominating organizations representing virtually every class of stakeholder in the profession: large academic and clinical umbrella organizations, specialty societies, program director associations, regional societies, and relevant sister Boards, among others. This does constitute by far the largest number of nominating organizations and Directors of any ABMS Member Board, an arrangement that has the obvious disadvantage that it is often difficult to achieve speedy consensus on some issues. On the other hand, the arrangement does insure that the broadest possible range of constituent opinion is represented and heard on every issue. In addition, it is a practical fact of life that the entire workforce is needed because ABS administers the largest number of oral examinations–more than 1300 per year–of any surgical Board.

Fundamental Tenets Concerning Basic Certification

What follows is a brief overview of the principal tenets that in my personal opinion underlie the Board's philosophical conception of the meaning of basic certification. The first of these is the concept of essential content areas, each of which is held to be indispensable to the comprehensive education of a broadly based surgeon. These areas include: the alimentary tract; the abdomen and its contents; breast, skin, and soft tissue; the endocrine system; head and neck surgery; pediatric surgery; surgical critical care; surgical oncology; transplantation surgery; trauma/burns; and vascular surgery. The Board holds that a surgeon who wishes to obtain basic certification must have acquired during residency a broad cognitive knowledge of and a wide practical experience with each of these areas, to include diagnosis, preoperative evaluation, intraoperative technical familiarity, and postoperative care, including the management of complications.

What are the commonalities that bind these areas together? I contend that each is represented by one, some, or all of the following domains:

Domains that are critical to the competent performance of both the generalist and specialist general surgeon, with specific respect to patient care, irrespective of any ultimate concentration of practice interest

Domains in which, relative to other specialists, the properly trained general surgeon possesses broader knowledge of and has experienced greater exposure to the varied manifestations of those disease components associated with the area and is therefore better acquainted with the appropriate requirements for their total care. Parathyroid surgery is an example. Many surgeons in nongeneral surgical specialties are technically capable of performing a parathyroidectomy well. However, it is highly unlikely that most can care for or perhaps even recognize the presence of an MEN syndrome. That is the province of the specialist general surgeon

Domains in which the general surgeon has demonstrated both historical leadership and current engagement in the process of generating new knowledge and formulating new concepts, both technical and nontechnical. Breast disease and transplantation are examples of this definition

Domains in which the general surgeon demonstrates substantive participation in providing service to the public

And where is all this supposed to lead? What is it the intention to create? The sought after end point is this: to produce an individual who is broadly educated in and exposed to all of the essential content areas of General Surgery in as much breadth and depth as possible, and who may be truly expert in some; an individual who is reasonably undifferentiated and relatively versatile, capable of a broad range of independent practice.

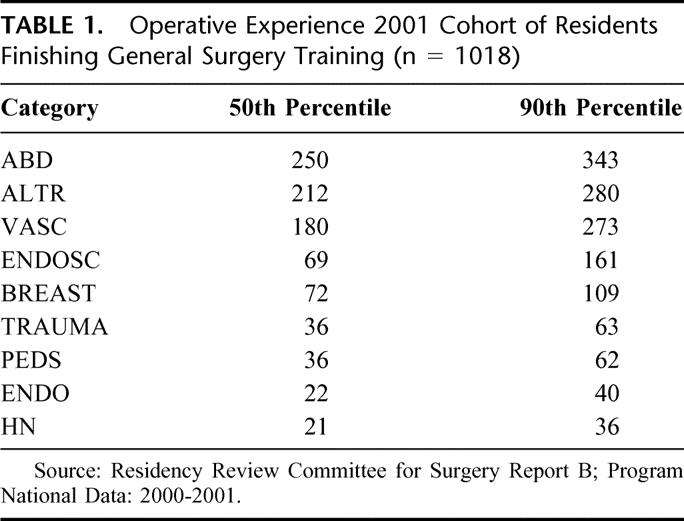

How well are these endpoints achieved? It is difficult to provide a precise answer. However, if one accepts procedural volume as an approximate surrogate for the goal, the data are encouraging (Table 1): a broad and relatively deep exposure by residents to procedures in those categories that comprise the essential content areas. Obviously, things could be improved upon (there is a 10th percentile, after all), but I believe the experience of most finishing Chief Residents is quite acceptable, especially when one considers the plethora of training programs and the very different venues in which they exist.

TABLE 1. Operative Experience 2001 Cohort of Residents Finishing General Surgery Training (n = 1018)

Even though General Surgery residents are trained relatively broadly, it is often pointed out that those who possess only the basic certificate tend to work over a much narrower range in practice. While the relative proportion between categories is roughly the same for practitioners as it is for residents, the absolute number of cases within categories is much smaller and in some cases nonexistent. This fact has led many to suggest that training should be made more efficient by focusing on what is actually done in the community. In my view,5 this approach would be a great mistake because it would totally destroy the most basic definition of an essential content area, ie, a domain critical to the education of a surgeon, irrespective of ultimate mode of practice. There are other reasons for subscribing to the belief that the basic surgical curriculum should be driven by educational considerations and not by current styles of work. For example, the average general surgeon participates in the operative care of very few major trauma victims. Does it follow, then, that surgical trainees should have minimal exposure to trauma surgery and all that it teaches with respect to understanding pathophysiology, instilling discipline, becoming facile with complex operative techniques, and providing total patient care, including critical care? Further, if the surgical curriculum of 25 years ago had faithfully reflected the practices then extant, endoscopy would never have achieved the prominent place it currently occupies in surgical training and patient care (13% of a general surgeon's practice).6 In my view, it is far preferable to strive at the outset to create a relatively adaptable and reasonably versatile surgeon than to try constantly to respond to an evanescent practice environment in which change occurs capriciously and often beyond the control of any of us.

In truth, the broadly educated basic general surgeon possesses great virtue, both real and potential, because, when trained in this way, such an individual can provide total patient care for much surgical disease; is capable of providing that care on a continuous basis; is “Captain of the Ship” because he/she expects and accepts ultimate patient care responsibility (consultation with specific experts for specific problems is totally appropriate but only one person is ultimately in charge and responsible); is probably cost effective; is better able by far to adapt to changing patterns of practice than one whose training has been more narrowly focused; is well prepared for what is still the required mode of practice in much of the United States today (it may not appear that this is the case when viewed from the perspective of Boston or Baltimore, but it definitely is the case in Bangor, Biloxi, Billings, and Bakersfield, and in hundreds of communities across the country just like them). Finally, of course, the concept has served the public quite well for almost two-thirds of a century.

With that as a background, it is now possible to define what I believe the Board believes the basic certificate is meant to signify:

That the individual has successfully completed an appropriate undergraduate medical education in an accredited institution in the United States or Canada or in a foreign medical school recognized by the World Health Organization (in this latter instance, the Board requires individuals to have achieved final certification by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates)

That the individual has successfully completed an accredited residency in Surgery, including a final year of senior responsibility

That during residency, the individual has acquired a breadth and depth of clinical experience acceptable to the Board in all of the essential content areas

That after careful and long observation, the Program Director has provided assurances to the Board that the individual possesses appropriate technical, diagnostic, and interpersonal skills and is also an ethical physician

That the individual has successfully completed the rigorous examination processes of the ABS

Parenthetically, it goes without saying that no one can achieve basic certification without a full and unrestricted license to practice in a jurisdiction of the United States or in Canada or its foreign equivalent.

There are, however, 2 important caveats to this definition, specifically 2 things that many erroneously believe the Board attributes to the certificate, but that it most emphatically does not and cannot. The first of these concerns the relationship of the basic certificate to clinical privileging. The position of the Board in this regard is explicit, relevant to all the certificates that it awards, and carefully spelled out in the ABS Booklet of Information:

“It is not the purpose, intent or role of the Board to define the requirements for membership on the staff of hospitals or institutions involved in the practice or teaching of surgery, nor to designate who shall or shall not perform surgical procedures or any category thereof. Privileging decisions are best made by locally constituted bodies based on an assessment of the applicant's extent of training, depth of experience, and patient outcomes relative to peers.”

The reasons for this stand are 2-fold. The first involves considerations of antitrust. For the Board to issue certificates selectively, that is, to some candidates but not to others (regardless of the criteria used), and to claim at the same time immutable special privilege for those who hold them but to no one else, represents a clear instance of an attempt at restraint of trade, a certain violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. To make such a claim would inevitably invite the immediate attention of the Justice Department, an exercise that no Board could even remotely afford. Equally distastefully, such a stance would make the Board a party to every local privileging dispute anywhere in the United States.

The second reason is also the second caveat and relates to the possession of specific competencies for specific procedures. The Board is fully cognizant of the fact that basic surgical training is a heterogeneous exercise because it involves a wide spectrum of training programs of variable quality, some of whose graduates may be less than optimally educated. Many are weeded out by the examination process, but some almost certainly are not. The Board recognizes that possibility, again very specifically, in the ABS Booklet of Information:

“Possession of a certificate is not meant to imply that a Diplomate is competent in the performance of the full range of complex procedures that encompass each content area...particularly advanced operations and treatments of a specialized nature. ...”

It is the Board's strongly held conviction that the most appropriate arbiters in this regard are local credentialing and privileging bodies based on the criteria outlined above as well as on local needs, local culture, and local circumstances.

Challenges to Basic Certification

Tensions and pressures on (and outright challenges to) this conceptualization of the meaning of basic certification clearly exist. Some are new but many have been extant for a considerable period of time. The oldest of these relates to specialization and the legitimate desire to be recognized for special expertise. Specialization is the natural and inevitable offshoot of accumulated new knowledge and advances in technology; as a result, specialization is not only inevitable, but also eminently desirable and supportable.

However, difficulties arise when inappropriate attempts are made to franchise that knowledge and to co-op that technology in an effort to stake out inviolate practice territory. The ultimate endpoint of that approach is to shatter completely the hegemony of the basic discipline, to balkanize it, and to fragment it into surgical sushi. The late Alex Walt, a wise, prescient, and deeply learned man once cogently explained the difference:

“In my view, fragmentation is essentially a state of mind that breeds instability and disharmony in contrast to specialization that is enhancing, desirable and inevitable. I would define specialization as intense exposure to a defined technique or body of knowledge. ... Fragmentation, in turn, is specialization onto which there is grafted a mindset or pattern of behavior characterized by a drive toward intellectual apartheid and functional secession from erstwhile colleagues, certifying boards or specialty societies. While human, this impulse toward unique recognition is usually driven by a desire to be substantially free from the modulating influence of the parent body. In such an environment beset by fragmentation, to quote W. B. Yeats, ‘Things fall apart; the center cannot hold…the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.’”7

The Board has recently experienced this phenomenon. In defense of the ABS, let me state that, in all of my years at the Board, I cannot recall an instance in which I thought it had acted deliberately to obstruct the legitimate development of any specialty within its traditional purview. However, it is also clear to me that in the past it occasionally appeared to be, and was, insensitive and sluggish in dealing with deeply felt specialty concerns. It also made a number of decisions that could have been interpreted—indeed, were interpreted—as demeaning to a specialty interest. Most importantly, it clearly failed to effect adequate formal engagement of at least one specialty because it did not provide it in a public and ongoing way with appropriate involvement into what many specialists felt were critically important decisions concerning its future.

When all of this became apparent, the Board recognized that it had a large and deep-seated problem that required a major reassessment of how it functioned. After considerable and far-reaching consultation and discussion, the Board radically restructured its entire system of governance in 1998. To address the concerns of all new emerging specialties as well as older established ones, the ABS created Specialty Boards and Advisory Councils within the Board itself (the Vascular Surgery Board of the American Board of Surgery is an example), composed of equal numbers of Directors of the Board who work within the specialty and appointees from the relevant specialty nominating organizations. The details of the reorganization are outlined elsewhere.8 Suffice it to say that the explicit intent of ABS was to cede to the intraboard Boards and Advisory Councils the power and responsibility for originating all initiatives within the specialty relating to the entire gamut of Board activities and requirements; to bring these initiatives to fruition; and, with the concurrence of the full Board of Directors of the ABS when needed, to oversee all aspects of implementation. Again, the purpose was simple: to let the specialties be masters of their own fates and to direct their own futures, but to do so within a commonwealth system of governance. It is my view that this schema has functioned well for the last 5 years and that it is not unreasonable to believe that the arrangement will serve as an effective template for other specialties in the future.

No one is so naive as to think that these actions will obviate all of the tensions that exist between generalists and specialists and the reason is that those tensions are inherent to progress. However, I do not believe that the generalist-specialist interface must always be grating and confrontational. That unhappy eventuality can be blunted as long as the generalist recognizes the benefits and the inevitability of specialization while, at the same time, the specialist recognizes that he or she can't own anything in surgery. No patents are awarded in this enterprise, and that is appropriate. The occasional claim that every single new approach or procedure is so complex and so difficult that only an anointed few are capable of utilizing them is simply not invariably true; some are, no doubt, but most are not because, even if true initially, expertise filters with time into the larger ranks first of residents in training and then of practitioners. This is a particularly appropriate sequence for those approaches and procedures that involve a common or emergent clinical problem.

In my view, the essential roles of specialists in today's world should be these:

To act as the principal catalyst for the creation of new knowledge and technology in the discipline

To educate its next generation of masters

To use their advanced skills to care for the truly complex, truly difficult, and truly unusual problems inherent in the specialty

To recognize and fulfill their undoubted obligation to expand and refine current generalist skills and capabilities in the discipline, especially, as noted, for common and emergent problems, because that serves the best interests of the public

There exist 3 additional current issues that have the potential for affecting the meaning and value of the basic certificate. Each is hugely important but also hugely complex. The first of these, discussed in detail elsewhere,9 relates to the “competence initiative” of the ABMS, a major effort by that organization to enhance the meaning of all certificates offered by its Member Boards by embedding within them a measurable assessment of competent performance in practice and to do so on an ongoing basis throughout a Diplomate's entire professional lifetime. No Board, including ABS, is under the illusion that creating this linkage will be easily accomplished. Nevertheless, despite the caveats outlined above, the ABS is strongly committed to the program because it is morally appropriate to do so. In fact, the Board will shortly field test a process by which individual Diplomates will be required to compare their patient outcomes, a valid surrogate for many elements of competence, with national norms to complete the process of recertification. The ABS has only one purpose in mind for this exercise—to improve the standards of surgical care that a Diplomate delivers to patients.

The remaining 2 issues, curricular reform and alternative training schemata, have been discussed extensively at 2 retreats held by the Board over the last 18 months. Those discussions convinced the Directors that, first, the time had come (indeed, was probably past due) to affect major reform of General Surgery training by creating, in essence, a competency-based curriculum through extensive restructuring of process, particularly in the early years. The Board has already embarked on this undertaking and has been joined in the effort by the American Surgical Association and the American College of Surgeons, among other organizations. The program is very much a work in progress at present.

At the same time, the Directors, compelled in part by externally imposed conditions, recognized the growing urgency of undertaking at long last a critical evaluation of a concept that has been peripherally discussed for years but one whose time many feel may now have come: the creation of a modified pathway to certification for specialty groups currently certified by ABS. Mindful of the fact that correcting problems identified in haste leads to implementing solutions regretted at leisure, the Directors recognized the wisdom of exploring the concept completely and objectively and of doing so now in relative calm rather than later in a maelstrom. To fail to initiate a pilot so-called “Early Specialization Program” would also clearly justify the charge that the Board is obdurate and obstructionist, and it would inevitably fuel attempts to separate and fragment. With that in mind, the Directors approved in principle the concept of performing a carefully crafted experiment in 1 or 2 specialty disciplines in carefully chosen programs under rigidly controlled conditions. Basic certification would still require a full 5 years exposure to the essential content areas but, in the pilot program, the training sequence could be altered such that the final year would be spent in the essential content area represented by the specialty and would be creditable toward both the basic and the specialty certificates (this last has already received the blessing of the ABMS). In order for the program to be considered successful, it will be required at a minimum to meet one essential condition: the meaning and value of the basic certificate must be maintained intact. Therefore, the endpoints of the experiment are concrete and stringent. They include success rates on the Surgery Qualifying and Certifying Examinations and the ability to achieve the procedural breadth, depth, and volume required by the Residency Review Committee for Surgery.

The Task Ahead

The fundamental task ahead for ABS is, I believe, to implement the best of the new while preserving the best of the old. I confess to being an unreconstructed Burkean conservative in this regard (as the tenor of this essay clearly indicates). As such, I believe that those responsible for directing the graduate surgical education enterprise should not rush to adjust to the perceived exigencies of today (which may well be transient) by sacrificing the accumulated lessons, wisdoms, and values of the past, all of which have served to produce the finest system of surgical education in the world and all of which are, in my opinion, embedded in the concept of basic certification. Those lessons, wisdoms, and values include 8 critically important principles for which I strongly believe the Board and its constituents should serve as advocates. They are:

Graduated, supervised, and incremental resident responsibility for patient care

Critical dissection of all untoward outcomes including those created by the systems in which we work.

The importance of sound basic and clinical science as an underpinning to the understanding and treatment of human disease

The virtue of a scholarly training environment

The primacy of education over service

The need for broad in-depth training in all of the essential content areas of the discipline of Surgery

The concept of total care of the patient—consultation as necessary and appropriate but no medicine by committee. The Mona Lisa wasn't painted by a committee, and good medicine isn't practiced that way either

The principle of continuous care throughout the course of a patient's entire illness

These are the essential elements of the graduate surgical education system, which in my view make it work so well. To sacrifice any of them on any altar, whatever its name, is to place the welfare of patients with surgical disease at inexcusable risk. They should be our line in the sand.

Footnotes

Reprints: Wallace P. Ritchie, Jr., MD, PhD, American Board of Surgery, 1617 John F. Kennedy Blvd., Suite 860, Philadelphia, PA 19103–1847.

The views expressed in this communication are solely those of the author; they should not be interpreted as reflecting the official position of the American Board of Surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stanley JC. Presidential address: the American Board of Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veith FJ. The case for an independent American Board of Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:619–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster MW. Presidential address: a belated obituary. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:826–830.11700482 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravitch MM. The American Board of Surgery. In: Ravitch MM, ed. A Century of Surgery: The History of the American Surgical Association, Vol. 2. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.; 1981:1542–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie WP Jr, Rhodes RS, Biester TW. Letter to editor re: vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2000;232:149–150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritchie WPJr, Rhodes RS, Biester TW. Work loads and practice patterns of general surgeons in the United States 1995–1997: a report from the American Board of Surgery. Ann Surg. 1999;230:533–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walt AJ. Implications of fragmentation in surgery on graduate training and certification. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1986;71:2–6, 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer JE. Chairman's report. ABS News. Sept. 1998.

- 9.Ritchie WPJr. The measurement of competence: current plans and future initiatives of the American Board of Surgery. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2001;86:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]