Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to determine whether abdominal drainage is beneficial after elective hepatic resection in patients with underlying chronic liver diseases.

Summary Background Data:

Traditionally, in patients with chronic liver diseases, an abdominal drainage catheter is routinely inserted after hepatic resection to drain ascitic fluid and to detect postoperative hemorrhage and bile leakage. However, the benefits of this surgical practice have not been evaluated prospectively.

Patients and Methods:

Between January 1999 and March 2002, 104 patients who had underlying chronic liver diseases were prospectively randomized to have either closed suction abdominal drainage (drainage group, n = 52) or no drainage (nondrainage group, n = 52) after elective hepatic resection. The operative outcomes of the 2 groups of patients were compared.

Results:

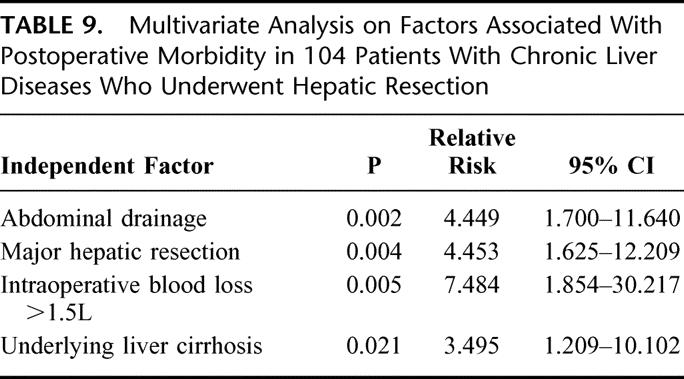

Fifty-seven (55%) patients had major hepatic resection with resection of 3 Coiunaud's segments or more. Sixty-nine (66%) patients had liver cirrhosis and 35 (34%) had chronic hepatitis. Demographic, surgical, and pathologic details were similar between both groups. The primary indication for hepatic resection was hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 100, 96%). There was no difference in hospital mortality between the 2 groups of patients (drainage group, 6% vs. nondrainage group, 2%; P = 0.618). However, there was a significantly higher overall operative morbidity in the drainage group (73% vs. 38%, P < 0.001). This was related to a significantly higher incidence of wound complications in the drainage group compared with the nondrainage group (62% vs. 21%, P < 0.001). In addition, a trend toward a higher incidence of septic complications in the drainage group was observed (33% vs. 17%, P = 0.07). The mean (± standard error of mean) postoperative hospital stay of the drainage group was 19.0 ± 2.2 days, which was significantly longer than that of the nondrainage group (12.5 ± 1.1 days, P = 0.005). With a median follow-up of 15 months, none of the 51 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the drainage group developed metastasis at the drain sites. On multivariate analysis, abdominal drainage, underlying liver cirrhosis, major hepatic resection, and intraoperative blood loss of >1.5L were independent and significant factors associated with postoperative morbidity.

Conclusion:

Routine abdominal drainage after hepatic resection is contraindicated in patients with chronic liver diseases.

A total of 104 patients who had underlying chronic liver diseases were prospectively randomized to have either closed suction abdominal drainage or no drainage after elective hepatic resection. Patients with abdominal drainage were found to have a significantly higher incidence of postoperative morbidity and a significantly longer hospital stay.

Without good scientific evidence, prophylactic drainage of the peritoneal cavity after abdominal surgery has been widely practiced for centuries.1–3 Recent reports have suggested that many abdominal surgical procedures can be performed safely without drainage.4–7 Traditionally, in patients who undergo hepatic resection, abdominal drain is routinely inserted into the subphrenic or subhepatic space closed to the resection surface. This serves to release the intra-abdominal tension due to ascitic fluid accumulation and allows the monitoring of the occurrence of postoperative intra-abdominal bleeding, as well as the detection and drainage of any bile leakage. The drainage catheter is usually removed toward the end of first week after the operation. However, the need for routine abdominal drainage after hepatic resection has been challenged.8 Two recent prospective randomized trials showed that minor hepatectomy9 or major hepatectomy for a normal liver10 is safe without abdominal drainage. However, the number of patients with chronic liver diseases was small in both studies. Hepatic resection for patients with chronic liver diseases is associated with the phenomenon of accumulation of ascites.11 Such a phenomenon is related to preexisting malnutrition and transient impaired liver function, which is secondary to the loss of functioning liver mass and hypoxic or ischemic injury to the liver remnant. The risk of postoperative bleeding may also increase if there are associated portal hypertension, thrombocytopenia, and impaired clotting profile. Most surgeons therefore advise abdominal drainage after hepatic resection in these patients. However, the benefits of such surgical practice are unclear. On the other hand, abdominal drains are not without risk: they have been reported to result in bowel injury, increased rates of intra-abdominal and wound infection, increased abdominal pain, decreased pulmonary function, and prolonged hospital stay.7,12–15 Patients with chronic liver diseases are more susceptible to postoperative morbidity, especially septic complications. It is therefore also unclear whether abdominal drainage is associated with an adverse outcome in this group of patients. A prospective randomized study was therefore performed to determine whether abdominal drainage is beneficial after elective hepatic resection in patients with chronic liver diseases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients who had underlying chronic liver diseases and underwent elective hepatic resection for intrahepatic pathologies between January 1999 and March 2002 were considered suitable candidates in this study. Exclusion criteria included patients who had a normal liver, a concomitant hepatico-enteric anastomosis, and patients’ refusal to enter the study. Informed consent for the study was obtained from all the patients, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital. A total of 120 patients were randomized initially to have either closed suction abdominal drainage (drainage group) or no drainage (nondrainage group) after hepatic resection by drawing consecutive sealed envelops. The result of randomization was only made known to the operating surgeon at the end of hepatic resection after hemostasis was completed and just before closure of the abdominal wound. Although all patients were suspected to have chronic liver diseases on preoperative evaluation and gross examination of the livers during laparotomy, 9 patients were found to have normal liver without evidence of chronic liver diseases and 7 patients were found to have fatty change of liver only on histologic examination of the resected specimen. These 16 patients were therefore excluded retrospectively from the study after randomization. The remaining 104 patients, including 52 patients in the drainage group and 52 patients in the nondrainage group, were the subjects of the present study.

Preoperative investigation of the patients included blood biochemistry, alpha-fetoprotein assay, chest x-ray, percutaneous ultrasonography, computed tomography of the abdomen, indocyanine green clearance test, and hepatic angiography in selected cases.16 Hepatic resection was performed following the standard technique described previously,17,18 and an ultrasonic dissector was used for parenchymal transection.19 In patients who were randomized to the drainage group, a closed suction silicon drain (Jackson-Pratt, Baxter Health Care Corp.; Deerfield, IL) was inserted before abdominal wound closure into the subphrenic or subhepatic space close to the transection surface at the end of the operation. The drain was brought out through a separate stab wound on the anterior abdominal wall and connected to a closed system with low suction pressure.

All patients received the same perioperative care by the same team of surgeons and were nursed in the intensive care unit during the early postoperative period. Careful attention was paid in the management of intravenous fluid and electrolyte during the early postoperative period. Intravenous fluid was restricted to <2 L/day without any intravenous sodium to minimize sodium and fluid retention and ascites accumulation in patients with chronic liver disease. In patients who underwent major hepatic resection, postoperative total parenteral nutrition with branched-chain amino acid rich fluid was given for about 5 days until oral intake was satisfactory.20 All intraoperative complications and postoperative morbidities were recorded prospectively by a single research assistant. Significant leakage of ascitic fluid from the abdominal wound or drain site after drain removal of >50 mL/day and for more than 3 days was considered a postoperative complication. Persistent output from the drain itself, regardless of the amount of drainage, was not considered a complication. In the drainage group, the abdominal drains were removed on postoperative day 5, unless there was excessive output from the drain of >200 mL/day. In patients who experienced leakage of ascites from the main wound or drain site after drain removal, various methods including suturing of drain site or leakage site from main abdominal wound, pressure dressing, and oral diuretic were used to control the leakage. Routine transcutaneous ultrasonography was performed on all patients on postoperative day 7 by experienced radiologists with the use of 2 to 4 MHz transcutaneous ultrasound probes (XP10, Acuson, Mount-View, CA) to detect any perihepatic collection of ascitic fluid in the subphrenic and subhepatic spaces. Size of collection was graded according to the thickness of fluid collection on ultrasound as no collection, mild collection (<2 cm), moderate collection (≥2 cm and <5 cm), and large collection (≥5 cm). Hospital mortality was defined as death during the same period of hospitalization for the hepatic resection. Clinical data of all patients were recorded prospectively in a computerized database, and the operative outcomes of the 2 groups of patients were compared. Statistical analysis was performed by the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test to compare discrete variables. The t test was used to compare continuous variables. Survival analysis was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier survival method. Statistical comparison of survival distributions was analyzed by log-rank tests. Multivariate analysis was performed using the logistic regression model to identify independent factors that were associated with postoperative morbidity. Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 11.0 for Windows computer software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Numeric values are expressed in mean ± standard error of mean unless otherwise stated. The patient sample size calculation was performed according to the estimations of a 40% local wound complication rate in the drainage group and a 15% local wound complication rate in the nondrainage group. Requiring a level of statistical significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, 100 patients were planned to be included in the study.

RESULTS

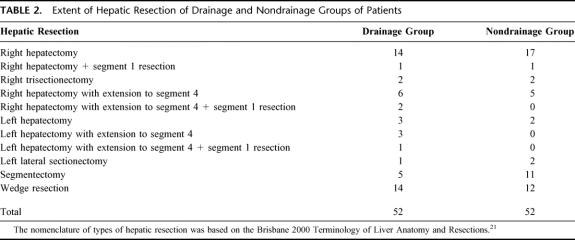

Among the 104 patients included in the study, there were 86 (83%) men and 18 (17%) women with a mean age of 53.2 ± 1.4 years (range, 30–74 years). The predominant cause for chronic liver diseases was related to chronic hepatitis B infection, and 93 (89%) patients were found to have a positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen. Although all patients had a preoperative diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), HCC was only confirmed on histology in 100 (96%) patients. One patient in the drainage group was found to have focal nodular hyperplasia, and 3 patients in the nondrainage group were found to have cirrhotic regenerative nodules on histologic examination of the resected specimens. Histologic examination also confirmed that 69 (66%) patients had underlying liver cirrhosis and 35 (34%) patients had chronic hepatitis. The clinicopathological parameters were comparable in both groups of patients (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Clinical and Laboratory Data of Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

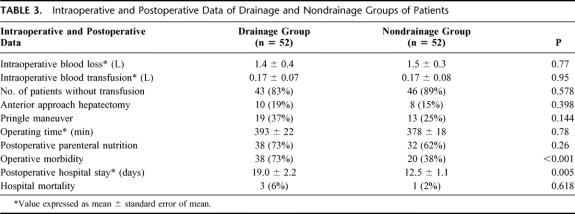

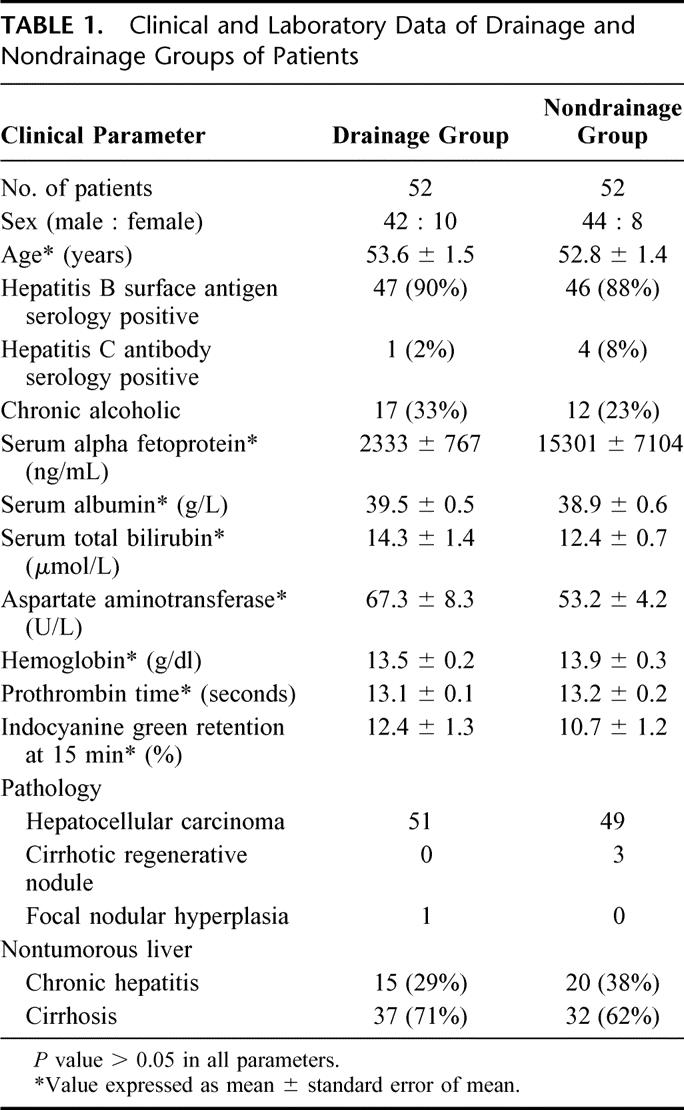

The extent of hepatic resection in both groups of patients is listed in Table 2.21 Thirty-two (62%) patients in the drainage group and 27 (52%) patients in the nondrainage group underwent major hepatic resection with resection of ≥3 Coiunaud's segments22 (P = NS). The mean intraoperative blood loss was 1.5 ± 0.4 L, and 86% of the patients did not require a blood transfusion (Table 3). Hospital mortality occurred in 3 (6%) patients in the drainage group and 1 (2%) patient in the nondrainage group (P = NS), all of whom had undergone major hepatic resection. Causes of death in the drainage group included intra-abdominal sepsis and liver failure (n = 1), chest infection and liver failure (n = 1), and liver failure (n = 1). The cause of death of the patient in the nondrainage group was chest infection and liver failure.

TABLE 2. Extent of Hepatic Resection of Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

TABLE 3. Intraoperative and Postoperative Data of Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

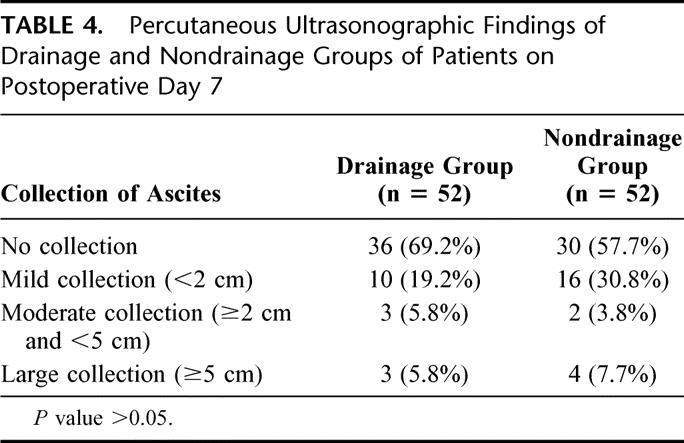

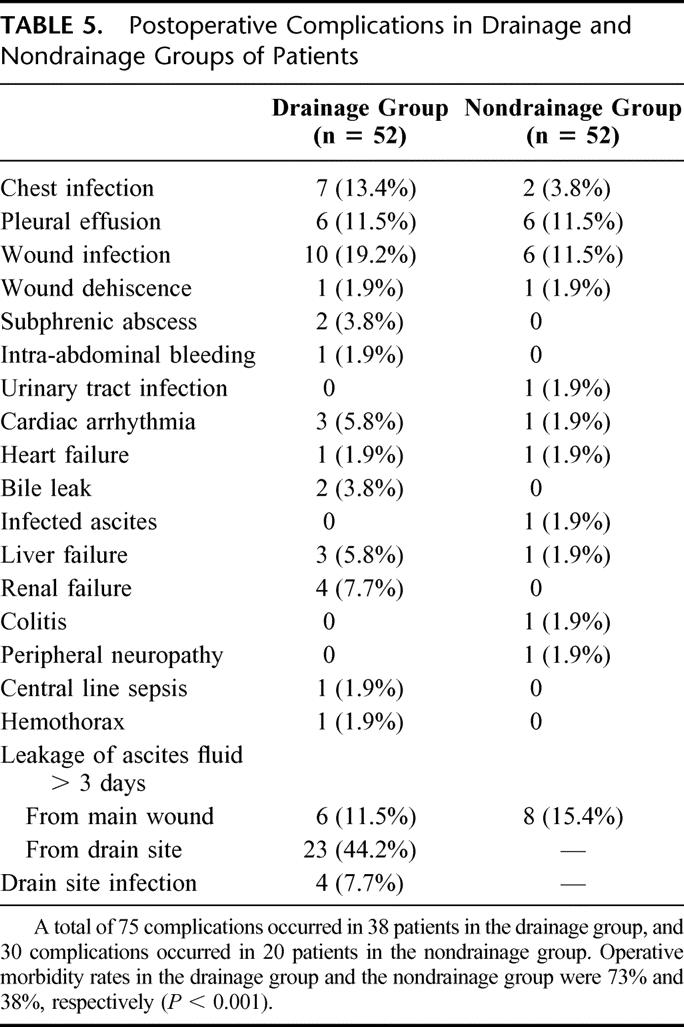

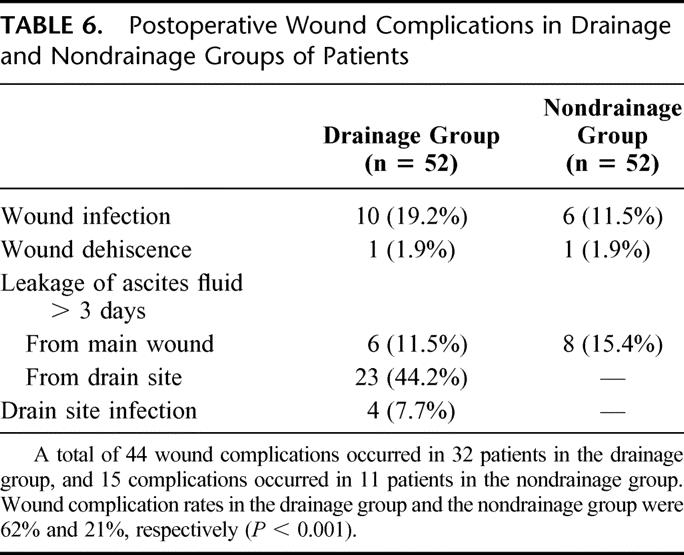

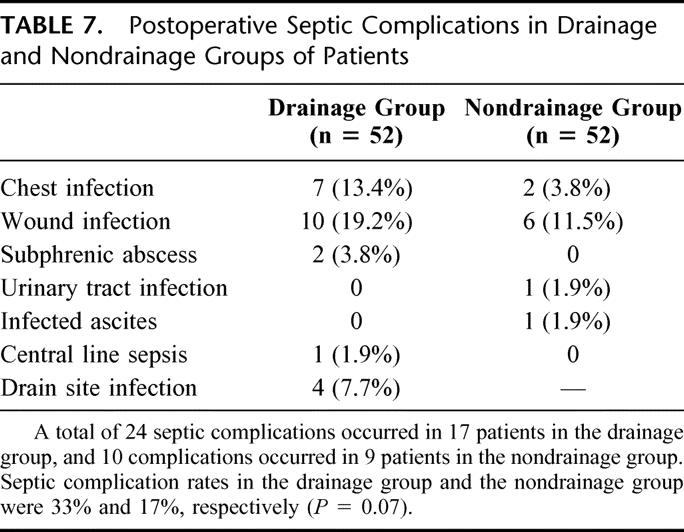

In the drainage group, 40 (77%) patients had the abdominal drain removed on postoperative day 5 and the drains were removed in all patients by postoperative day 9. Routine percutaneous ultrasonography to detect intra-abdominal collection was performed on day 7 after hepatic resection. Most (88%) of the patients were found to have no or mild collection of ascites only, and these findings were comparable in both groups (Table 4). A total of 105 complications occurred in 58 patients, resulting in an overall operative morbidity rate of 56% (Table 5). The operative morbidity rate in the drainage group was 73%, which was significantly higher than that in the nondrainage group (38%, P < 0.001). Thirty-two (62%) patients in the drainage group had a total of 44 wound complications (Table 6). These included wound infection (n = 10), wound dehiscence (n = 1), drain site infection (n = 4), and leakage of ascitic fluid from the main wound (n = 6) or drain site (n = 23) for more than 3 days. The incidence was significantly higher than that of nondrainage group, in which 15 wound complications occurred in 11 patients (21%, P < 0.001). In addition, a trend toward a higher incidence of septic complications was also observed in the drainage group compared with the nondrainage group (33% vs. 17%, P = 0.07, Table 7). A total of 24 septic complications occurred in 17 (33%) patients in the drainage group. These included chest infection (n = 7), wound infection (n = 10), subphrenic abscess (n = 2), central line sepsis (n = 10), and drain site infection (n = 4). Nine (17%) patients in the nondrainage group had a total of 10 septic complications. The mean (± standard error of mean) postoperative hospital stay of the drainage group was 19.0 ± 2.2 days, which was significantly longer than that of the nondrainage group (12.5 ± 1.1 day, P = 0.005).

TABLE 4. Percutaneous Ultrasonographic Findings of Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients on Postoperative Day 7

TABLE 5. Postoperative Complications in Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

TABLE 6. Postoperative Wound Complications in Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

TABLE 7. Postoperative Septic Complications in Drainage and Nondrainage Groups of Patients

Six (5.8%) patients required postoperative surgical or radiologic interventions for postoperative complications, including 5 patients (9.6%) in the drainage group and 1 patient (1.9%) in the nondrainage group (P = 0.2). Two patients developed postoperative bile leakage and 1 patient had intra-abdominal hemorrhage in the drainage group. The abdominal drains, however, failed to detect these complications in these 3 patients: The first patient developed symptoms and signs of intra-abdominal sepsis 8 days after hepatic resection and 3 days after removal of the abdominal drain. Bile leakage was detected when the patient underwent laparotomy. Consequently, the patient underwent biliary reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy and made an uneventful recovery. The second patient developed symptoms and signs of intrabdominal sepsis 5 days after hepatic resection before the abdominal drain was removed. There was no evidence of bilious output from the drainage catheter. CT scan of the abdomen showed a loculated collection close to the transection surface of the liver. Percutaneous drainage of the collection yielded bile-stained fluid, presumptively as a result of minor bile leakage from the transection surface of the liver. The third patient developed hypotension and a significant drop in hemoglobin on the first day after hepatic resection. The abdominal drain yielded very little blood-stained fluid. Subsequent re-exploration revealed hemoperitoneum and blockage of the abdominal drain with fresh clots. Two other patients in the drainage group developed postoperative subphrenic abscess that required CT-guided drainage (n = 1) and surgical drainage (n = 1). One patient in the nondrainage group required a relaparotomy for infected ascites.

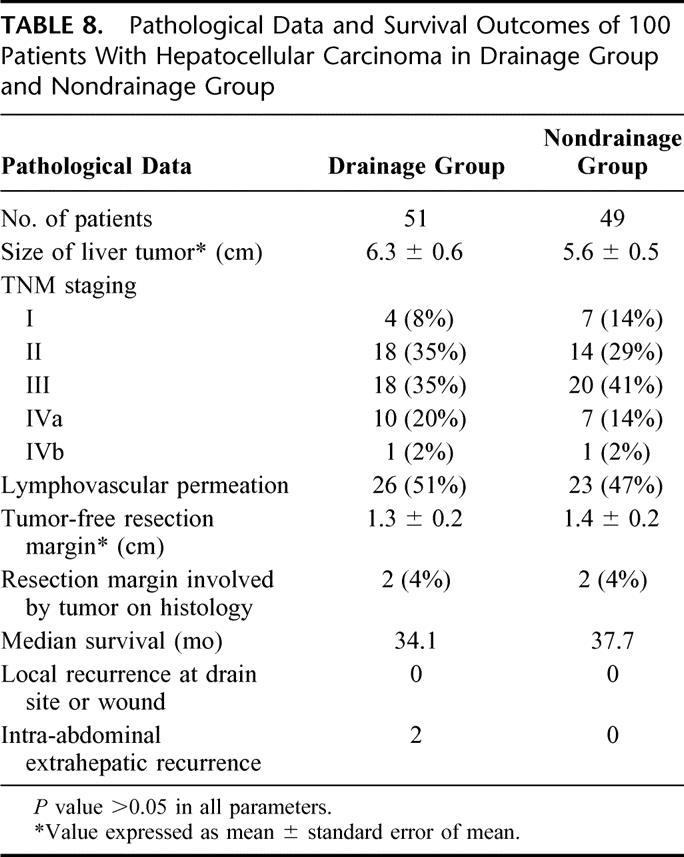

In the 100 patients who had the diagnosis of HCC confirmed on histologic examination of the resected specimen, pathologic data, including the TNM tumor staging, tumor size, resection margin, and number of patients with lymphovascular permeation, were comparable in both groups (Table 8). There was no statistical significant difference between the overall median survival of the drainage group (34.1 months) and the nondrainage group (37.7 months). With a median follow-up of 15 months, none of the 51 patients with HCC in the drainage group developed metastasis at the drain sites. Two patients who presented initially with spontaneous rupture of HCC in the drainage group developed intraperitoneal extrahepatic recurrence after hepatic resection.

TABLE 8. Pathological Data and Survival Outcomes of 100 Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Drainage Group and Nondrainage Group

Statistical analysis was performed on all 104 patients in the study to identify independent factors that were associated with postoperative morbidity. Fifteen factors were examined, including patient factors (age, sex, preoperative indocyanine green clearance, prothrombin time, serum albumin, serum total bilirubin, and underlying liver cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis), tumor factors (preoperative serum alpha-fetoprotein, size of tumor, and TNM tumor staging), and operative factors (extent of hepatic resection, anterior approach hepatic resection,18 intraoperative blood loss, transfusion requirement, and abdominal drainage). On multivariate analysis, abdominal drainage, underlying liver cirrhosis, major hepatic resection, and intraoperative blood loss >1.5 L were independent risk factors that were significantly associated with postoperative morbidity (Table 9).

TABLE 9. Multivariate Analysis on Factors Associated With Postoperative Morbidity in 104 Patients With Chronic Liver Diseases Who Underwent Hepatic Resection

DISCUSSION

Abdominal drainage has been a routine practice for many years, and the drain is usually inserted into the subphrenic or subhepatic space close to resection surface after hepatic resection.11 This serves to relieve intra-abdominal tension due to ascitic fluid accumulation, to monitor the occurrence of postoperative intra-abdominal bleeding, and to detect for bile leakage.11 Indeed, abdominal drainage after hepatic resection was our routine practice previously, except for patients with normal livers who underwent minor resections. Over the past decade, before the present study was conducted, 393 hepatic resections for HCC had been performed in our institution. Of these, 366 (93%) patients had abdominal drainage. Unfortunately, the practice of drainage after hepatic resection was not based on any scientific evidence. In general, the prophylactic values of postoperative drainage in abdominal surgery remain controversial. Previous studies showed no benefit of using closed suction drainage after a variety of intra-abdominal procedures, such as colorectal resection,7 closure of perforated duodenal ulceration,15 or cholecystectomy.14

In a nonrandomized study reported by Franco et al,8 the complication rate of 61 patients who underwent a liver resection without abdominal drainage was 8%. The authors suggested that routine use of drains was unnecessary. Belghiti et al9 reported a prospective randomized study on 81 patients, who were randomized to have either closed suction drainage or no drainage after hepatic resection. The overall complication rates appeared similar between the 2 groups. However, postoperative ultrasonography showed that there was a significantly greater rate of subphrenic collections in patients who had a minor hepatic resection in the drainage group. These collections were also more frequently infected in the drainage group. However, the number of patients with cirrhosis or who underwent major hepatic resection was relatively small (23% and 31%, respectively).

Similar results were reported by Fong et al,10 who prospectively randomized 120 patients either to have abdominal drainage or not after hepatic resection. No significant difference between the 2 groups was observed with regard to the rates of mortality and morbidity, the length of hospital stay, or the need for subsequent percutaneous drainage. Three patients developed an infected subhepatic collection in the drainage group, whereas there was none in the nondrainage group. Although the number of patients with the complication was not large enough to determine whether drainage was truly responsible, the observation was consistent with that reported by Belghiti et al.9 Since the patients included in the study reported by Fong et al10 were mainly noncirrhotic, postoperative complications mostly related to patients with chronic liver diseases, including ascitic leakage from wound and drain site and possible increase in septic complications, were not evaluated.

Our current study was designed to evaluate whether abdominal drainage after hepatic resection was beneficial or harmful to patients with chronic liver diseases. Our results showed that abdominal drainage resulted in increased postoperative morbidity related to a higher incidence of wound complications and a trend toward more septic complications. As a result of increased postoperative morbidity, the hospital stay of the patients in the drainage group was significantly longer. On multivariate analysis, abdominal drainage was also identified to be 1 of the 4 independent risk factors that significantly associated with postoperative morbidity. The results of the present study differed from those of the 2 previous prospective randomized studies, showing statistically significant inferior operative outcomes of patients with abdominal drainage. The results were also consistent with those from an earlier prospective study on open cholecystectomy reported by Monson et al,14 suggesting that intraperitoneal drainage was associated with an increased postoperative morbidity. The mean hospital stay of the patients in the drainage group was 6.5 days longer than that of the patients in the nondrainage group in the present study. Assuming that the daily cost of hospital stay was U.S.$400 and that about 100 patients underwent elective hepatic resection per year in our institution, U.S.$260,000 can theoretically be saved per year by avoiding the routine use of abdominal drainage.

One of the theoretical advantages of abdominal drainage in patients with chronic liver disease is for the drainage of ascitic fluid after hepatic resection, so as to release the intra-abdominal pressure, resulting in improvement of postoperative abdominal distending discomfort and minimizing splintage of the diaphragms. However, in this study, the extent of ascitic fluid collection as evaluated by postoperative ultrasonography was similar in both groups. In addition, the incidence of respiratory failure or chest infection was not higher in the nondrainage group. It was therefore reasonable to conclude that abdominal drainage did not result in reduction of ascitic fluid collection. On the contrary, significant leakage of ascitic fluid from the drain site was observed in 44% of the patients. The leakage led to a continuous soaking of the abdominal wound, difficulty in application of wound dressing and nursing care, and discomfort and mental distress of the patient. This invariably resulted in a prolonged hospital stay. Continuous soaking of abdominal wound with possible contaminated ascitic fluid might also contribute to an increase in the incidence of wound infection.

Surgical or radiologic intervention for postoperative complications was required in 6 patients, 5 of whom were in the drainage group. This finding represented a paradox to the traditional idea that abdominal drainage after hepatic resection could prevent accumulation of fluid, whether infected or not, including ascitic fluid, bile, and blood around the liver. However, our observation was consistent with the data reported by Monson et al,14 who showed that a statistically significant increase in subhepatic collections in patients with abdominal drainage after cholecystectomy compared with those without drainage (18% vs. 1.8%, P < 0.01) probably resulted from ascending infection. Increased risks of overall morbidity and septic complications associated with abdominal drainage have also been reported after splenectomy and liver trauma.13,23,24 Similar to the postulation of the reason for increased postoperative anastomotic leakage after pancreatic resection in patients with abdominal drainage,5 excessive suction force on the transection surface of the liver could also be a contributing factor to the postoperative biliary leakage and intra-abdominal hemorrhage observed in the drainage group of patients in the present study.

Over the past few decades, hepatic resection has evolved from a risky and heroic procedure to one accepted as an effective therapy for many benign and malignant diseases with minimal mortality and acceptable morbidity. Biliary fistula and postoperative hemorrhage are much less frequently encountered nowadays, which were 2% and 1%, respectively, in the present series. Especially when shown to be associated with increased postoperative morbidity by the present study, routine placement of abdominal drains in all patients with the intention to detect these complications in only a few patients is not justified. One of the most serious complications associated with abdominal drainage after hepatic resection for malignant diseases is recurrence at the drainage site.25 Fortunately, none of our 51 patients with HCC in the drainage group developed this complication on follow-up. In the present series of 104 patients with chronic liver diseases, among whom 66% had liver cirrhosis, the hospital mortality was 4%. Three patients in the drainage group died in hospital, among whom 2 died of sepsis and liver failure, including 1 patient with subphrenic abscess. While it remained unclear whether sepsis and liver failure would still occur or the operative outcome of these patients would have been different if abdominal drain were not placed, they probably did not gain much benefit from the abdominal drainage.

CONCLUSION

In patients with chronic liver diseases undergoing elective hepatic resection, abdominal drainage is associated with a significantly higher postoperative morbidity related to significantly more wound complications, a trend toward more septic complications, and a significantly longer hospital stay. Routine abdominal drainage after hepatic resection is contraindicated in patients with chronic liver diseases.

Footnotes

Reprints: Dr. Chi-Leung Liu, Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong Medical Centre, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China. E-mail: clliu@hkucc.hku.hk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moss JP. Historical and current perspectives on surgical drainage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;152:517–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson JO. Surgical drainage: an historical perspective. Br J Surg. 1986;73:422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty SH, Simmons RL. The biology and practice of surgical drains. Part 1. Curr Probl Surg. 1992;29:559–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SR, Gilmore OJ. Surgical drainage. Br J Hosp Med. 1985;33:308, 311, 314––308, 311, 315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlon KC, Labow D, Leung D, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 2001;234:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeekel J. No abdominal drainage after Whipple's procedure. Br J Surg. 1992;79:182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merad F, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, et al. Is prophylactic pelvic drainage useful after elective rectal or anal anastomosis?A multicenter controlled randomized trial. French Association for Surgical Research. Surgery. 1999;125:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco D, Karaa A, Meakins JL, et al. Hepatectomy without abdominal drainage: results of a prospective study in 61 patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:748–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belghiti J, Kabbej M, Sauvanet A, et al. Drainage after elective hepatic resection: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1993;218:748–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fong Y, Brennan MF, Brown K, et al. Drainage is unnecessary after elective liver resection. Am J Surg. 1996;171:158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bona S, Gavelli A, Huguet C. The role of abdominal drainage after major hepatic resection. Am J Surg. 1994;167:593–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson R, Saarela A, Tranberg KG, et al. Intraabdominal abscess formation after major liver resection. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:707–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillmore D, McSwain NEJr, Browder IW. Hepatic trauma: to drain or not to drain? J Trauma. 1987;27:898–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monson JR, Guillou PJ, Keane FB, et al. Cholecystectomy is safer without drainage: the results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1991;109:740–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pai D, Sharma A, Kanungo R, et al. Role of abdominal drains in perforated duodenal ulcer patients: a prospective controlled study. Aust NZ J Surg. 1999;69:210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan ST, Ng IO, Poon RT, et al. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: the surgeon's role in long-term survival. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y. Liver resection for benign diseases and for liver and biliary tumors. In: Blumgart LH, ed. Surgery of the Liver and the Biliary Tract, 3rd ed. London: Saunders, 2000:1639–1713. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Anterior approach for major right hepatic resection for large hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2000;232:25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan ST, Lai EC, Lo CM, et al. Hepatectomy with an ultrasonic dissector for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan ST, Lo CM, Lai EC, et al. Perioperative nutritional support in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strasberg SM, Belghiti J, Clavien PA, et al. The Brisbane 2000 terminology of liver anatomy and resections. HPB. 2000;2:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couinaud C. Etudes Anatomiques et Chirurgicales. Paris: Mason, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerise EJ, Pierce WA, Diamond DL. Abdominal drains: their role as a source of infection following splenectomy. Ann Surg. 1970;171:764–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stanford GG, et al. Factors affecting morbidity following hepatic trauma: a prospective analysis of 482 injuries. Ann Surg. 1991;213:540–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koffi E, Moutardier V, Sauvanet A, et al. Wound recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:301–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]