Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to describe the lymphatic drainage patterns from the 5 “quadrants” of the breast.

Summary Background Data:

Lymphatic mapping has provided techniques to visualize and harvest sentinel nodes in various locations and has generated renewed interest in nodes outside the axilla.

Methods:

Between January 1997 and June 2002, 700 sentinel node procedures were performed in patients with cN0 breast cancer. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy was performed after injection of 99mTc-nanocolloid into the tumor in a volume of 0.2 mL and a mean dose of 107.7 MBq (2.8 mCi). Intraoperatively, the sentinel node was pursued with the aid of a gamma-ray detection probe and patent blue dye (1.0 mL, into the lesion). The patients were divided into 5 groups according to the location of the primary breast cancer. In each group, a distinction was made between palpable and nonpalpable lesions of the breast.

Results:

Drainage to either an axillary or an extra-axillary basin was observed in 678 patients. Both palpable and nonpalpable lesions may drain toward the internal mammary chain, although the latter more frequently, regardless of the quadrant. Drainage was also observed to supraclavicular, infraclavicular, interpectoral, and intramammary sentinel nodes.

Conclusion:

In each quadrant, a breast cancer may drain to sentinel nodes in various locations. There is a distinct difference in drainage patterns between palpable and nonpalpable lesions. These findings may improve the assessment of lymphatic dissemination in invasive breast cancer.

This study describes in detail the drainage routes from the different regions of the breast to the axillary and extra-axillary lymph nodes, based on 700 sentinel node procedures.

The existence of lymphatic drainage of the breast to axillary and extra-axillary sites has been known for centuries.1 Although also these latter nodes are known to sometimes contain metastatic disease, their removal has never been pursued enthusiastically. Interest in drainage patterns of breast cancer, however, is growing since the introduction of the sentinel node procedure. Lymphatic mapping allows visualization and identification of sentinel nodes and the possibility to document the drainage patterns.

The aim of this study was to describe the drainage patterns in all breast cancer patients who underwent a sentinel node procedure at our institute. Our intratumoral tracer injection technique enables accurate visualization of drainage from the actual primary tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 1997 and June 2002, 691 cN0 breast cancer patients underwent 700 sentinel node biopsy procedures at The Netherlands Cancer Institute. Nine patients had a bilateral tumor and 152 patients had a nonpalpable tumor. Pathologic proof of breast cancer was routinely obtained by core biopsy or fine needle aspiration. The primary tumor was still present in all patients.

A 2-day protocol was used. On the day before surgery, 99mTc-nanocolloid (Nanocoll, Amersham Cygne, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) was injected into the lesion in a mean volume of 0.2 mL and a mean radioactivity dose of 107.7 MBq (2.8 mCi). In case of nonpalpable breast cancer, the intratumoral injection was guided by ultrasound or stereotaxis. Static imaging was performed at 30 minutes and 4 hours postinjection. A dual-head gamma camera (ADAC Vertex, Milpitas, CA) was used. Since July 1999, additional views were obtained after 2 hours. Both anterior and lateral images were obtained. The location of the node was marked on the skin with indelible ink. Patent blue dye (Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) and a gamma ray detection probe (Neoprobe, Johnson & Johnson Medical, Hamburg, Germany) were used to identify the sentinel node. All procedures were performed by 1 of 4 experienced surgeons or under their supervision by a resident or fellow. A hot spot on the lymphoscintigram was considered to be a sentinel node either if an afferent lymphatic channel was visualized or the hot spot was the first one seen in a sequential pattern, or the hot spot was the only one depicted. An afferent blue lymphatic vessel coming directly from the tumor also defined a node as the sentinel node. The sentinel node regions suggested by lymphoscintigraphy were verified intraoperatively.

Extra-axillary regions were explored only in case of lymphoscintigraphic visualization. Internal mammary chain sentinel nodes were explored either through the incision made for the removal of the primary tumor or through a small separate transverse incision over the intercostal space concerned. After splitting the pectoral muscle fibers, the intercostal muscles were separated from the lower rib to expose the fatty tissue along the internal mammary vessels on the surface of the parietal pleura. Never was a rib divided.

All sentinel nodes were formalin-fixated, bisected, paraffin-embedded, and cut at a minimum of 6 levels at 50- to 150-μm intervals. Pathologic evaluation included hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemical staining (CAM 5.2, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Patient characteristics and both lymphoscintigraphic and surgical results were recorded prospectively. Only patients with drainage from the tumor, either visualized during lymphoscintigraphy or identified during operation, were included in the study. The patients were divided into 5 groups according to the location of the primary breast cancer: upper outer quadrant (UOQ), upper inner quadrant (UIQ), lower outer quadrant (LOQ), lower inner quadrant (LIQ), and center (C). In each group, an extra distinction was made between palpable and nonpalpable lesions of the breast. The χ2 test was performed to evaluate differences in drainage between various patient groups.

RESULTS

Drainage Patterns

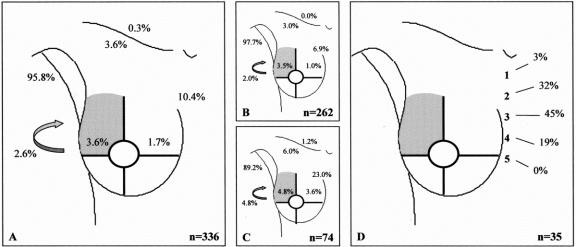

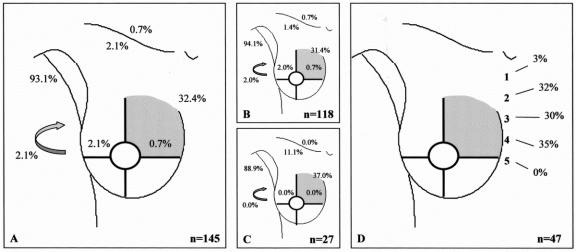

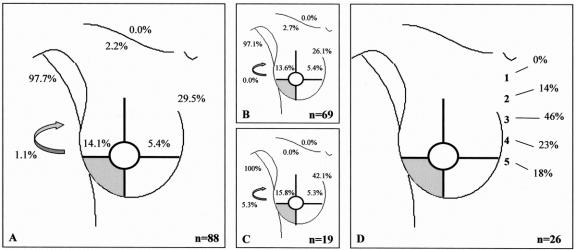

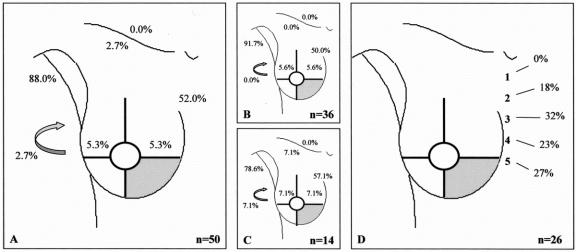

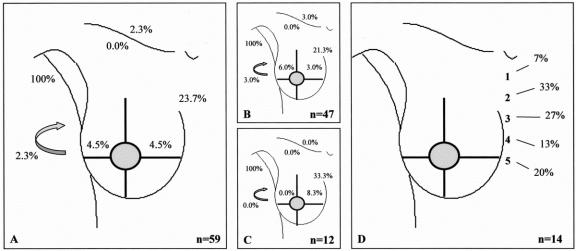

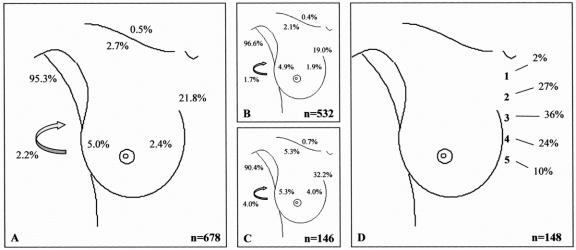

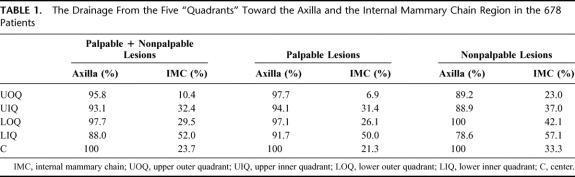

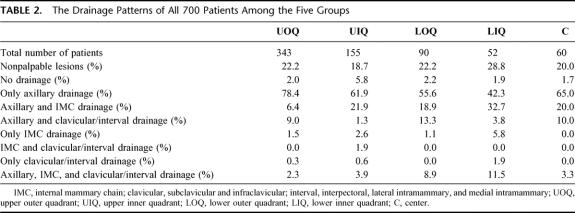

In 22 of the 700 procedures, no drainage was observed. The drainage patterns of the remaining 678 patients from each “quadrant” of the breast toward the axilla (levels I and II), the internal mammary chain, the lateral and medial intramammary regions, the interpectoral region, and to the subclavicular (level III) and supraclavicular regions are shown in Figures 1 to 5. The drainage pattern of all 678 patients combined is presented in Figure 6. In case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region, the intercostal space location of that sentinel node is given in the subfigures D. Table 1 shows the drainage toward the axilla and the internal mammary chain region. Both palpable and nonpalpable lesions may drain toward the internal mammary chain, although the latter more frequently, regardless of the quadrant (P = 0.001). Nonpalpable lesions in the UOQ, UIQ, and LIQ have less often drainage to the axilla compared with the palpable breast lesions. All lesions from the center drain to the axilla. The outer quadrants show drainage to the internal mammary chain in 14.4%, which is less than the inner quadrants (37.4%, P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1. Drainage pattern from the upper outer quadrant. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

FIGURE 2. Drainage pattern from the upper inner quadrant. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

FIGURE 3. Drainage pattern from the lower outer quadrant. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

FIGURE 4. Drainage pattern from the lower inner quadrant. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

FIGURE 5. Drainage pattern from the center. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

FIGURE 6. Drainage pattern from the whole breast. A: All breast lesions. B: Palpable breast lesions. C: Nonpalpable breast lesions. D: Intercostal space location of the sentinel node in case of drainage to the internal mammary chain region. Arrow, interpectoral region.

TABLE 1. The Drainage From the Five “Quadrants” Toward the Axilla and the Internal Mammary Chain Region in the 678 Patients

The drainage patterns for each “quadrant” in all 700 patients are shown in detail in Table 2.

TABLE 2. The Drainage Patterns of All 700 Patients Among the Five Groups

Pathology

The axilla was tumor-positive in 212 of 657 (32%), the internal mammary chain (IMC) was tumor-positive in 19 of 148 (13%), and other extra-axillary sentinel nodes were tumor-positive in 14 of 87 patients (16%). In 16 patients, the axilla was tumor-free while the extra-axillary sentinel nodes harbored metastases.

DISCUSSION

This study describes lymphatic drainage pathways from the breast. An advantage of our technique of intratumoral tracer administration is that it allows visualization of lymph drainage from the actual breast cancers. The small volumes that were injected limit the risk of disturbing the normal physiology. Sentinel node biopsy was always performed with the primary tumor still present, so there was no risk of disruption of lymphatics. Several observations were made. In addition to the axilla and the internal mammary node chain, drainage occurs to other locations in and around the breast in a substantial percentage of the patients. Nonpalpable tumors drain more frequently to the internal mammary chain, irrespective of the quadrant. The LIQ has less drainage to the axilla compared with the other quadrants, but more to the internal mammary chain. The lateral side of the breast often drains to the internal mammary chain as well (10–30%).

We have described our hypothesis on the finding of more extra-axillary drainage in nonpalpable breast cancer patients in a recent study.2 In that study, the percentage of visualized extra-axillary sentinel nodes in nonpalpable breast cancer patients was 43% and differed significantly from the visualization rate in palpable tumors (24%). Anatomic studies dealing with the arrangement of the breast lymphatics show that internal mammary nodes and interpectoral nodes are supplied by retromammarian lymphatics.3,4 These lymphatics arise from the breast lobules, run on the surface of the pectoral fascia, and accompany penetrating blood vessels on their way through the pectoral and intercostal muscles. The finding that a deep tracer injection in particular will visualize extra-axillary sentinel nodes supports the observation that deep lymphatics from the dorsal part of the breast drain to these nodes. Deeper located tumors are less accessible to palpation. So, the depth of the tumor may be the explanation of the difference in drainage to extra-axillary sentinel nodes between palpable and nonpalpable lesions.

Lymphatic drainage patterns from various regions of the breast have been studied once before the sentinel node era. In 1972, Vendrell-Torne et al used an intraparenchymal radioactive gold administration and a conventional scanner that depicts less detail than the now ubiquitous gamma cameras.5 Their study performed in normal individuals without breast cancer showed frequent drainage to the internal mammary chain. Tracer administered in the UOQ traveled there in 36% of the cases and for the LOQ this was 64%. The LIQ drained even more frequently to the internal mammary nodes than to the axilla (86% vs. 68%). Vendrell-Torne et al5 did not observe drainage to intramammary or interpectoral nodes, perhaps due to the primitive equipment that was used at the time and the lack of intraoperative confirmation of the exact location of the sentinel node seen on the scan.

The development of lymphatic mapping has generated a renewed interest in drainage patterns because a sentinel node may be located outside the axilla. Paganelli et al have shown that tracer administration deep in the parenchyma of the inner quadrants travels to internal mammary nodes in 66% of the cases, whereas these nodes are seen in just 10% when the tracer is administered in an outer quadrant.6 Drainage to nodes elsewhere around the breast was not observed. Byrd et al also found that 10% of UOQs drain to the internal mammary chain.7 For the LOQ, UIQ, and LIQ, these percentages were 27%, 17%, and 25%, respectively. No nodes outside the axilla or the internal mammary chain were described. Uren et al found drainage to sentinel nodes outside the axilla in a surprisingly high 56%.8

The clinical relevance of extra-axillary sentinel nodes and, in particular, the internal mammary chain sentinel nodes is being debated.9,10 Some investigators have taken it upon them to pursue these nodes and to take their tumor status into account when making a treatment plan. Our group has shown that internal mammary chain sentinel nodes can be harvested in 87% of the patients.11 A stage migration of 16% in these patients was observed and led to a better selection of patients who might benefit from postoperative radiotherapy to the internal mammary chain and from adjuvant systemic treatment.11 Other surgeons are following suit, and the current study may increase their awareness of where to expect sentinel nodes.12–16

Footnotes

Reprints: Susanne H. Estourgie, MD, Department of Surgery, The Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail:s.estourgie@nki.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Camper P. Over den waren aart der kankervorming en over een zeer zakelijk en onfeilbaar teken van onherstelbaaren borstkanker. Geneeskd Nat Huishoudkd Kabinet. 1779;2:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanis PJ, Deurloo EE, Valdés Olmos RA, et al. Single intralesional tracer dose for radio-guided excision of clinically occult breast cancer and sentinel node. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan I. Revision anatomique du systeme lymphatique de la glande mammaire (a propos de 200 cas). Bull Assoc Anat (Nancy). 1975;59:121–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haagensen CD, Feind CR, Herter FP, et al. The Lymphatics in Cancer. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vendrell-Torne E, Setoain-Quinquer J, Domenech-Torne FM. Study of normal mammary lymphatic drainage using radioactive isotopes. J Nucl Med. 1972;11:801–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paganelli G, Galimberti V, Trifiro G, et al. Internal mammary node lymphoscintigraphy and biopsy in breast cancer. Q J Nucl Med. 2002;46:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd DR, Dunnwald LK, Mankoff DA, et al. Internal mammary lymph node drainage patterns in patients with breast cancer documented by breast lymphoscintigraphy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uren RF, Howman-Giles R, Renwick SB, et al. Lymphatic mapping of the breast: locating the sentinel lymph nodes. World J Surg. 2001;25:789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon JM, Dobie V, Chetty U. The importance of interpectoral nodes in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:334–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugg SL, Ferguson DJ, Posner MC, et al. Should internal mammary nodes be sampled in the sentinel lymph node era? Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estourgie SH, Nieweg OE, Valdés Olmos RA, et al. Should the hunt for internal mammary chain sentinel nodes begin? 56th Annual Cancer Symposium Soc Surg Oncol. March 5–9, 2003, Los Angeles. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Galimberti V, Veronesi P, Arnone P, et al. Stage migration after biopsy of internal mammary chain lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:924–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Ent FW, Kengen RA, van der Pol HA, et al. Halsted revisited: internal mammary sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noguchi M, Tsugawa K, Miwa K. Internal mammary chain sentinel lymph node identification in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupont E, Cox CE, Nguyen K, et al. Utility of internal mammary lymph node removal when noted by intraoperative gamma probe detection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cody HS III, Urban JA. Internal mammary node status: a major prognosticator in axillary node-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]