Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the efficacy of imipenem, piperacillin combined with cecropin B in the prevention of lethality in 2 rat models of septic shock. Main outcome measures were bacterial growth in blood and intra-abdominal fluid, endotoxin and TNF-α concentrations in plasma, and lethality.

Background:

Sepsis remains a serious clinical problem despite intense efforts to improve survival. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. The primary cause of Gram-negative shock results from activation of host effector cells by endotoxin, the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) associated with cell membranes of Gram-negative bacteria.

Methods:

Adult male Wistar rats were given (1) an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS or (2) 2 × 1010 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922. All animals were randomized to receive intraperitoneally isotonic sodium chloride solution, 1 mg/kg cecropin B, 20 mg/kg imipenem, and 120 mg/kg piperacillin alone and combined with 1 mg/kg cecropin B. Each group included 20 animals.

Results:

All compounds reduced the lethality when compared with controls. Piperacillin and imipenem significantly reduced the lethality and the number of E. coli in abdominal fluid compared with saline treatment. On the other hand, each betalactam determined an increase of plasma endotoxin and TNF-α concentration. Combination between cecropin B and betalactams showed to be the most effective treatment in reducing all variables measured.

Conclusion:

Cecropin B enhances betalactams activities in Gram-negative sepic shock rat models.

Sepsis remains a serious clinical problem despite intense efforts to improve survival. The efficacy of imipenem, piperacillin combined with cecropin B in the prevention of lethality in 2 rat models of septic shock was investigated. Their combinations showed to be the most effective treatment in reducing all variables measured.

Sepsis remains a serious clinical problem despite intense efforts to improve survival. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients and all immunocompromised subjects.1–4 The lipopolysaccharide (LPS), composed of an O-polysaccharide chain, a core sugar, and a lipophilic fatty acid (lipid A), is one of the most important bacterial components involved in the pathogenesis of Gram-negative infection activating the host effector cells through stimulation of receptors on their surface.1,5 These target cells secrete large quantities of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-8, platelet-activating factor, arachidonic acid metabolites, erythropoietin, and endothelin.5–7

The underlying principles of therapy have remained unchanged for decades. They are based on prompt institution of antimicrobial agents aimed at the inciting pathogen, source control directed at removal of the infection nidus whenever possible, and support of organ dysfunction.8 Nevertheless, several studies have indicated that exposure of Gram-negative organisms to antibacterial agents can result in endotoxin release. However, even though some observations have suggested that this phenomenon could have deleterious effects, its clinical relevance has not been well defined.9–11 To date, the list of potential therapeutic targets has been growing, and many compounds have been used to treat septic shock: monoclonal antibodies to endotoxin, IL-1 receptor antagonists, antioxidants, and various antiinflammatory therapies; despite these advances, the mortality from sepsis-related diseases have remained substantially unchanged.1–4,12

Antimicrobial peptides are positively charged molecules isolated from a wide variety of animals and plants. Most of these molecules, natural or synthetic, are amphipathic and have a broad spectrum of activity against bacteria, fungi, and protozoa; in addition, in recent years they received increasing attention because they possess anti-endotoxin activity.13–19 In fact, polycationic peptides bind to the negatively charged residues of LPS of the outer membrane by electrostatic interactions involving the negatively charged phosphoryl-groups and by hydrophobic interactions involving the acyl chains of lipid A. This binding is the key mechanistic step in the killing of Gram-negative organisms and endotoxin inactivation.19 Among these compounds, cecropin B is a positively charged peptide that was originally isolated from the hemolymph of the giant silk moth. Similarly to other polycationic peptides, it possesses 2 important activities: broad antimicrobial spectrum and anti-endotoxin activity.17–19

The present experimental study was performed to assess the potential therapeutic role of cecropin B alone and combined with betalactams not only in treating Gram-negative infections but also in neutralizing the biologic effect of the endotoxin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (weight range, 250 to 300 g) were used for all the experiments. All animals were housed singly in standard cages and had access to chow and water ad libitum throughout the study. The environment was temperature and humidity controlled, with lights on and off at 6:30 AM and 6:30 PM. The study was approved by the animal research ethics committee of the I.N.R.C.A. I.R.R.C.S., University of Ancona.

Organisms and Reagents

The commercially available quality control strain of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used. Endotoxin (E. coli serotype 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich S.r.l., Milan, Italy) was prepared in sterile saline, aliquoted, and stored at –80°C for short periods.

Agents

Cecropin B was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. It was dissolved in distilled H2O at 20 times the required maximal concentration. Successively, for in vitro studies, serial dilutions of the peptide were prepared in 0.01% acetic acid containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin in polypropylene tubes; for in vivo experiments, it was diluted in physiological saline. Piperacillin (Wieth Lederle, Aprilia, Italy) and imipenem (Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Milan, Italy) powders were diluted in accordance with manufacturers’ recommendations. Solutions were made fresh on the day of assay.

Susceptibility Testing

Susceptibility testing was performed by microbroth dilution method according to the procedures outlined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards.20 However, since cationic peptides bind polystyrene, polypropylene 96-well plates (Sigma-Aldrich) were substitute for polystyrene plates.21 The MIC was taken as the lowest antibiotic concentration at which observable growth was inhibited. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Experimental Design

Two experimental conditions were studied: (1) intraperitoneal administration of LPS and (2) E. coli–induced peritonitis.

Six groups, each containing 20 animals, were anesthetized by an intramuscular injection of ketamine (30 mg/kg of body weight) and injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 mg of E. coli serotype 0111:B4 LPS in a total volume of 500 μL of sterile saline. Immediately after injection, animals received intraperitoneally isotonic sodium chloride solution (control group C0), 1 mg/kg cecropin B, 20 mg/kg imipenem, and 120 mg/kg piperacillin alone and combined with 1 mg/Kg cecropin B, respectively.

E. coli ATCC 25922 was grown in brain-heart infusion broth. When bacteria were in the log phase of growth, the suspension was centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 minutes, the supernatant was discarded, and the bacteria were resuspended and diluted into sterile saline. All animals (six groups, each containing 20 animals) were anesthetized as above mentioned. The abdomen of each animal was shaved and prepared with iodine. The rats received an intraperitoneal inoculum of 1 mL of saline containing 2 × 1010 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922. Immediately after bacterial challenge, animals received intraperitoneally isotonic sodium chloride solution (control group C1), 1 mg/kg cecropin B, 20 mg/kg imipenem, and 120 mg/kg piperacillin alone and combined with 1 mg/kg cecropin B, respectively.

Evaluation of Treatment

After treatment, the animals were returned to individual cages and thoroughly examined daily. On the basis of the kind of experiment, at the end of the study the rate of positivity of blood cultures, quantitation of bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid, and rate of lethality, toxicity, plasma endotoxin, and TNF-α levels were evaluated. Animals were monitored for the subsequent 72 hours.

Toxicity was evaluated on the basis of the presence of any drug-related adverse effects, ie, local signs of inflammation, anorexia, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and behavioral alterations.

The surviving animals (model 2) were killed with chloroform, and blood samples for culture were obtained by aseptic percutaneous transthoracic cardiac puncture. In addition, to perform quantitative evaluations of the bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid, 10 mL of sterile saline was injected intraperitoneally, samples of the peritoneal lavage fluid were serially diluted, and a 0.1-mL volume of each dilution was spread onto blood agar plates. The limit of detection was ≤ 1 log10 CFU/ml. The plates were incubated both in air and under anaerobic conditions at 35°C for 48 hours.

For determination of endotoxin and TNF-α levels in plasma, 0.2-mL blood samples were collected from the jugular vein after 0, 2, 6, and 12 hours after injection. During this time, a catheter was placed into the vein and sutured to the back of the rat.

Endotoxin concentrations were measured by the commercially available Limulus amebocyte lysate test (E-TOXATE, Sigma-Aldrich). Plasma samples were serially diluted 2-fold with sterile endotoxin-free water and were heat-treated for 5 minutes in a water bath at 75°C to destroy inhibitors that can interfere with the activation. The endotoxin content was determined as described by the manufacturer. Endotoxin standards were tested in each run and the concentrations of endotoxin in the text samples (in endotoxin units [EU/ml]) were calculated by comparison with the standard curve. TNF-α levels were measured by a commercially available solid phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Nuclear Laser Medicine, S.r.l., Settala, Italy) according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. The standards and samples were incubated with a TNF-α antibody coating 96-well microtitre plate. The wells were washed with buffer and then incubated with biotinylated anti-TNF-α antibody conjugated to streptavidin-peroxidase. This was washed away, and color was developed in the presence of chromogen (tetramethylbenzidine) substrate. The intensity of the color was measured in a microplate reader (MR 700 Dynatech Laboratories, Guernsey, UK) by reading the absorbance at 450 nm. The results for the samples were compared with the standard curve to determine the amount of TNF-α present. All samples were run in duplicate. The lower limit of sensitivity for TNF-α by this assay was 0.05 ng/ml. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 6.3% and 8.1%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

MIC values are presented as the average values obtained in triplicates on 3 independent measurements. Survival data were compared using logrank test. Qualitative results from blood and intra-abdominal fluid cultures were analyzed using χ,2 Yates's correction, and Fisher exact test, depending on the sample size. Quantitative evaluation of the bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid cultures were presented as mean ± SD of the mean; statistical comparisons between groups were made using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc comparisons were performed by Bonferroni's test. Plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test; multiple comparisons between groups were performed using the appropriate standard procedure. Each comparison group contained 20 rats. Significance was accepted when the P value was ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

In Vitro Susceptibility Studies

According to the broth-microdilution method, E. coli ATCC 25922 resulted differently susceptible to the compounds tested: the MICs of cecropin B, imipenem, and piperacillin were 2.00 mg/L, 0.11 mg/L, and 0.24 mg/L, respectively.

Intraperitoneal Administration of LPS

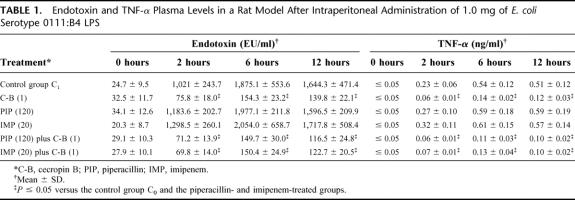

Intraperitoneal peptide treatments given immediately after administration of 1.0 mg of E. coli serotype 0111:B4 LPS were better than no treatment and intraperitoneal imipenem and piperacillin. In fact, there were significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) in plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels between the cecropin B-treated group compared with the control group C0 and the imipenem- or piperacillin-treated groups. In fact, treatments with cecropin B alone or combined with betalactams showed anti-endotoxin activity resulting in the lowest plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Endotoxin and TNF-α Plasma Levels in a Rat Model After Intraperitoneal Administration of 1.0 mg of E. coli Serotype 0111:B4 LPS

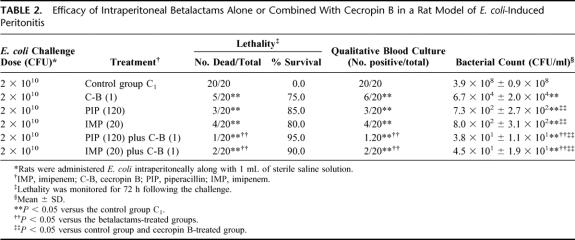

E. coli-Induced Peritonitis

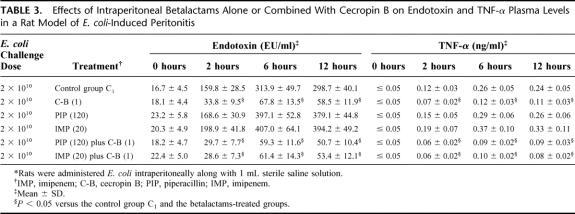

The rate of lethality in control group C1 was 100%. For groups treated with single drug, all intraperitoneal treatments given immediately after challenge were better than no treatment (P ≤ 0.05). Specifically, survival rates were 75.0%, 80.0%, and 85.0% in the groups treated with cecropin B-, imipenem-, piperacillin-treated, respectively (Table 2). Bacteriological evaluation showed 100% positive blood and intra-abdominal fluid cultures in control group C1; the average bacterial count in the peritoneal fluid from dead or surviving animals at 72 hours was 3.9 × 108 ± 0.9 × 108 CFU/ml. Piperacillin and imipenem showed the highest antimicrobial activities and therapeutic efficacies. In fact, there were significant differences in the results for the quantitative bacterial cultures when the data obtained from the betalactams-treated groups were compared with those obtained for the peptide-treated group (P ≤ 0.05). Endotoxin and TNF-α concentrations increased constantly in the control group C1, with mean peak levels achieved at 6 hours after injection (Table 3). Similarly, to experiment model 1, the cecropin B-treated groups showed significant reduction in plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels when compared with the control and betalactams-treated groups. Imipenem showed the highest plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels, nevertheless no significant difference in plasma endotoxin and TNF-α concentrations was observed among the imipenem-treated, piperacillin-treated, and the control group C1. Combination treatments demonstrated that the combinations between cecropin B and betalactams produced the highest survival rates (more than 90%). Contemporaneously, these combinations exhibited the highest antimicrobial activities and the strongest reduction in plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels. Finally, all agents did not show any toxicity; in fact none of the animals had clinical evidence of drug-related adverse effects, such as local signs of inflammation, anorexia, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and behavioral alterations.

TABLE 2. Efficacy of Intraperitoneal Betalactams Alone or Combined With Cecropin B in a Rat Model of E. coli-Induced Peritonitis

TABLE 3. Effects of Intraperitoneal Betalactams Alone or Combined With Cecropin B on Endotoxin and TNF-α Plasma Levels in a Rat Model of E. coli-Induced Peritonitis

DISCUSSION

Current treatments for Gram-negative septic shock rely on antibiotics to control the infection and intensive-care support to correct the dysfunction of the main organ systems. Nevertheless, after LPS liberation by antibiotics, the lipid A becomes available to interact adversely with host cells.1,5,7 On the basis of its highly conserved molecular structure among Gram-negative bacteria, the lipid A may be a logical target for agents designed to bind to LPS. The anionic and amphiphilic nature of lipid A enables it to bind either to compounds that are positively charged or to molecules that possess an amphipathic character.22–24 For these reasons, new strategies are investigated to treat not only the infection but also to neutralize the biologic effect of the endotoxin by the use of agents that would sequester LPS, thereby preventing its recognition by the host's effector cells. Over the last several years, a number of studies have described the interaction of LPS with several classes of cationic and/or amphipathic compounds.12,13,19

The present study describes the effects of intraperitoneal administration of 2 betalactam antibiotics, piperacillin and imipenem, alone and in combination with a positively charged peptide, cecropin B, on survival outcome, blood culture, intra-abdominal fluid bacterial content and plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels in 2 rat models of Gram-negative septic shock. Taken together, the results of this study demonstrated that all compounds reduced the lethality and the number of E. coli in the intra-abdominal fluid when compared with saline treatment. On the other hand, the betalactams determined an increase of plasma endotoxin and TNF-α concentrations. Interestingly, cecropin B produced a significant reduction in plasma endotoxin levels when compared with any other group, confirming its double antimicrobial and anti-endotoxin activity. Finally, combination between cecropin B and betalactams showed to be the most effective treatment in reducing all variables measured. In fact, the strongest results concerning the bacterial growth inhibition, lethality and endotoxemia were obtained when piperacillin and imipenem were administered in combination with cecropin B.

Several papers have been devoted to study animal models of septic shock.25 A single dose of endotoxin or a single inoculum of one Gram-negative species have been the most used models of sepsis for the screening of anti-endotoxin and antimicrobial drugs. Data analysis of our models did not show an essential different impact on parameters evaluation and it was evident that the efficacies of the compounds were not affected by the animal models used, and that these were retained regardless the system performed. However, the extrapolation of results from animal models to human pathology should be regarded with caution. Actually, these models are not definitively representative of what happens in clinical infections since humans are usually exposed not only to one species of Gram-negative bacteria but also to Gram-positive organisms and in different way.

Current treatments for Gram-negative septic shock rely on antibiotics to control the infection. On the other hand, it is known that many clinically used antibiotics can be harmful when administered to treat severe Gram-negative infections, in that they can stimulate the release of endotoxin and thus increase the occurrence of symptoms and life-threatening complications.11,25,26 Our results collectively show the feasibility of sequestering LPS by using cationic and amphiphilic compounds and suggest the potential therapeutic utility of polycationic peptides such as cecropin B when associated to other antimicrobial compounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the University of Ancona, Italy (Project Young Researchers 2000).

Footnotes

Reprints: Andrea Giacometti, MD, Clinica delle Malattie Infettive, c/o Ospedale Regionale, Via Conca, 60020 Torrette Ancona, Italy. E-mail: anconacmi@interfree.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hardaway RM. A review of septic shock. Am Surg. 2000;66:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenzel RP, Pinsky MR, Ulevitch RJ, et al. Current understanding of sepsis. J Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brun-Buisson C, Doyan F, Carlet J, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. JAMA. 1995;274:968–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Treating patients with severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone RC. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mira JP, Cariou A, Grall F, et al. Association of TNF2, a TNFα promoter polymorphism, with septic shock susceptibility and mortality. JAMA. 1999;282:5615–5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zervos E, Norman J, Denham D, et al. Cytokine activation through sublethal hemmorhage is protective against early lethal endotoxic challenge. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1216–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A, Anel RL. Experimental and emerging therapies for sepsis and septic shock. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1471–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J, McConnell JS. Antibiotic-induced endotoxin release. Lancet. 1985;ii:1069–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prins JM, Kuijper EJ, Mevissen MLCM, et al. Release of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6 during antibiotic killing of Escherichia coli in whole blood: influence of antibiotic class, antibiotic concentration, and presence of septic serum. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2236–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byl B, Clevenbergh P, Kentos A, et al. Ceftazidime- and imipenem-induced endotoxin release during treatment of gram-negative infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:804–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler EJ, Fisher CJ, Sprung CL, et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and septic shock with HA-1A human monoclonal antibody against endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gough M, Hancock REW, Kelly NM. Anti-endotoxin activity of cationic peptide antimicrobial agents. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4922–4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott MG, Yan H, Hancock REW. Biological properties of structurally related α-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2005–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Ghiselli R, et al. Effect of mono-dose intraperitoneal cecropins in experimental septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1666–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cirioni O, Giacometti A, Ghiselli R, et al. Single-dose intraperitoneal magainins improve survival in a gram-negative-pathogens septic shock rat model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:101–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore AJ, Beazley WD, Bibby MC, et al. Antimicrobial activity of cecropins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1077–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hultmark D, Steiner H, Rasmuson T, et al. Insect immunity. Purification and properties of three inducible bactericidal proteins from hemolymph of immunized pupae of Hyalophora cecropia. Eur J Biochem. 1980;106:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock REW, Chapple DS. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1317–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 5th Edition. Approved Standard. M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA, 2001.

- 21.Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Barchiesi F, et al. In vitro susceptibility tests for cationic peptides: comparison of microbroth dilution methods for bacteria that grow aerobically. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1694–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raetz CRH. Biochemistry of endotoxins. Ann Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David SA, Silverstein R, Amura CR, et al. Lipopolyamines: novel antiendotoxin compounds that reduce mortality in experimental sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:912–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwagaki A, Porro M, Pollack M. Influence of synthetic antiendotoxin peptides on lipopolysaccharide (LPS) recognition and LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine responses by cells expressing membrane-bound CD14. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1655–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker SJ, Watkins PE. Experimental models of Gram-negative sepsis. Br J Surg. 2000;88:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shenep JL, Barton RP, Mogan KA. Role of antibiotic class in the rate of liberation of endotoxin during therapy for experimental gram-negative bacterial sepsis. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]