Abstract

Objective:

To assess the real utility of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) in patients with cholangiocarcinoma, we need series with large numbers of cases and long follow-ups. The aim of this paper is to review the Spanish experience in OLT for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinoma and to try to identify the prognostic factors that could influence survival.

Summary Background Data:

Palliative treatment of nondisseminated irresectable cholangiocarcinoma carries a zero 5-year survival rate. The role of OLT in these patients is controversial, due to the fact that the survival rate is lower than with other indications for transplantation and due to the lack of organs.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed 59 patients undergoing OLT in Spain for cholangiocarcinoma (36 hilar and 23 peripheral) over a period of 13 years. We present the results and prognostic factors that influence survival.

Results:

The actuarial survival rate for hilar cholangiocarcinoma at 1, 3, and 5 years was 82%, 53%, and 30%, and for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma 77%, 65%, and 42%. The main cause of death, with both types of cholangiocarcinoma, was tumor recurrence (present in 53% and 35% of patients, respectively). Poor prognosis factors were vascular invasion (P < 0.01) and IUAC classification stages III–IVA (P < 0.01) for hilar cholangiocarcinoma and perineural invasion (P < 0.05) and stages III-IVA (P < 0.05) for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma.

Conclusions:

OLT for nondisseminated irresectable cholangiocarcinoma has higher survival rates at 3 and 5 years than palliative treatments, especially with tumors in their initial stages, which means that more information is needed to help better select cholangiocarcinoma patients for transplantation.

We reviewed 59 patients undergoing liver transplantation in Spain for cholangiocarcinoma (36 hilar and 23 peripheral). The actuarial survival rate for hilar at 1, 3, and 5 years was 82%, 53%, and 30%, and for peripheral 77%, 65%, and 42%. The main cause of death, with both types, was tumor recurrence.

The treatment of cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is controversial. When there is no tumor spread, the aim is curative resection of the tumor with free margins (R0 resection), which for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma (PCC) means a liver resection;1,2 for hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCC), it means resection of the bile duct, which is extended on occasions to a liver resection, depending on the location of the tumor, or a vascular resection.3–7 When there is evidence of tumor spread, only palliative treatments are indicated, which have very low survival rates.8,9 Lastly, there are cases where, in the absence of tumor spread, the tumor is considered locally irresectable. In such cases, a possible alternative to palliative treatment is orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), although its utility in these patients is controversial due to the lack of organs and to the possibility of immunosuppression accelerating the progression of unidentified tumor remains.10–12 To assess the real utility of OLT in these patients, we need series with large numbers of cases and long follow-ups.

The aim of this paper is to review the Spanish experience in OLT for PCC and HCC and to try to identify the prognostic factors that could influence survival.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

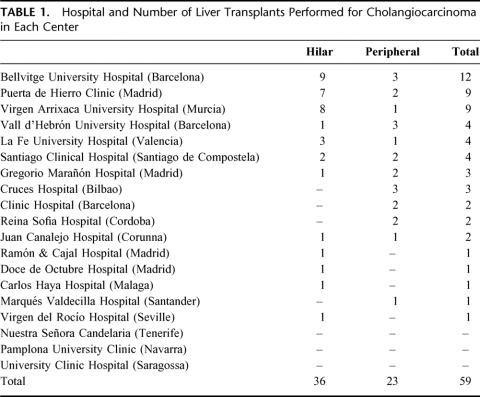

We performed a retrospective multicenter study including all patients undergoing OLT in Spain for CC (Table 1). The study covers the period from March 1988 (date of the first transplant in Spain for CC) to September 2001. For HCC, we used the Bismuth-Corlette classification to determine tumor location.13 Tumor staging was done using the TNM classification of the IUAC, both for hilar and peripheral CC.14

TABLE 1. Hospital and Number of Liver Transplants Performed for Cholangiocarcinoma in Each Center

We reviewed 59 patients with OLT for CC (36 hilar and 23 peripheral). In the distribution by years into 2 time periods (1988–1994 and 1995–2001), we noted a slight increase in the number of OLTs performed for this reason in the second period (21 cases [36%] in the first period versus 38 cases [64%] in the second).

Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 36)

The mean age of the patients was 44 years (range, 20–63); 26 (72%) were men. In 4 cases, tumor diagnosis was incidental: in 3 the indication for transplantation was primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC); the other was a sclerosing cholangitis secondary to hepatic hydatidosis that had already received numerous operations.

In 22 patients, the tumor was considered irresectable without extrahepatic disease by the results of complementary examinations, and OLT without previous exploratory laparotomy was indicated. Exploratory laparotomy was indicated with a view to surgical resection in the remaining 14 cases, of which 11 could not undergo any surgical intervention due to the tumor being considered irresectable though not disseminated. Surgical interventions were possible in the remaining 3: in one case, a right trisegmentectomy for a CC formed over a choledochal cyst invading the hepatic hilus, with OLT indicated after recurrence in the left hepatic duct; in another case, resection of the entire common bile duct, due to a papillary tumor (Bismuth type II), plus Roux-en-Y reconstruction, with OLT indicated after recurrence in the hepatic ducts; in the remaining case, local resection of a Bismuth type II tumor (T2N0M0), in which the histologic study revealed microscopic invasion of the resection margins (R1 resection), for which OLT was indicated.

None of the patients received preoperative treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. OLT was done in all cases, with 2 recipients prepared in case the tumor had spread during the waiting time. The surgical technique in all cases consisted of a lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilus and common hepatic artery and resection of the whole common bile duct as far as the pancreas and Roux-en-Y reconstruction of the donor bile duct. A cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy (CPD) was associated in 2 cases.

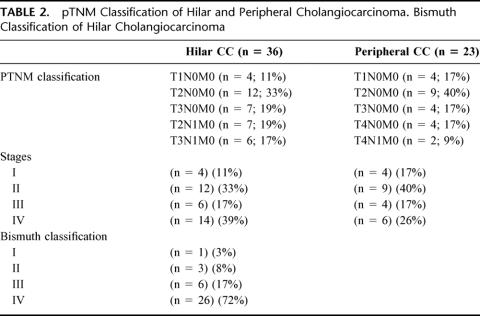

Eighty-nine percent of the patients were Bismuth types III–IV; in the final staging after OLT, 44% of the patients were early stages I—II; the rest were stages III–IVA (Table 2).

TABLE 2. pTNM Classification of Hilar and Peripheral Cholangiocarcinoma. Bismuth Classification of Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

Peripheral Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 23)

The mean age of the patients was 54.4 years (range, 25–68); 14 (61%) were men. In 10 cases, tumor diagnosis was established incidentally, with OLT indicated in 4 cases for decompensation of a hepatic cirrhosis and in 6 for PSC. One 25-year-old female patient was diagnosed with CC over a Caroli disease, and 3 cases had a false preoperative diagnosis of hepatocarcinoma that was confirmed as CC by histology. None of the patients received preoperative or postoperative treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

OLT was indicated in 9 of the 13 patients, with a preoperative diagnosis of CC because the preoperative examinations informed of an irresectable tumor without evidence of extrahepatic disease. In the remaining 4, exploratory laparotomy was indicated for resection purposes, with OLT indicated on finding that the tumor was irresectable, with no evidence of tumor spread. One diabetic patient had a pancreas transplant associated with the OLT. In the definitive staging after OLT, 57% of the patients were stages I—II; the rest were stages III–IVA (Table 2).

Statistical Method

To conduct the study, a questionnaire was sent out to all the OLT units. From the results obtained, an analysis of the actuarial survival curves was done using the Kaplan-Meier method; for comparison of the survival curves, the Breslow and Mantel tests were used. We also conducted a univariate analysis of the prognostic factors with the χ2 test and multivariate analysis with Cox's regression model. The values were statistically significant (SS) for P < 0.05.

The prognostic factors analyzed for hilar CC were as follows: age (< and > 50 years); gender; tumor location (Bismuth I–II versus III–IV); incidental nature; staging with or without laparotomy prior to OLT; postoperative treatment with chemotherapy (5-fluoruracyl) and external radiotherapy; lymph node, parenchymal (T3), vascular, and perineural invasion in the histologic study of the specimen; pTNM classification and pTNM classification stages (stages I–II versus stages III–IV). The prognostic factors analyzed for peripheral CC were as follows: age (< and > 50 years); gender; incidental nature; staging with or without laparotomy prior to OLT; postoperative treatment with chemotherapy (5-fluoruracyl) and external radiotherapy; lymph node, parenchymal (T3), vascular and perineural invasion in the histologic study of the specimen; pTNM classification and pTNM classification stages (stages I–II versus stages III–IV).

RESULTS

Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 36)

Tumor Recurrence

Nineteen patients (53%) presented with tumor recurrence. The most common site of recurrence was the abdominal cavity with 13 cases (liver, duodenopancreas, retroperitoneum), the bone in 3 cases, pulmonary metastases in 1 case, skin in 1 case, and multiple metastases in 1 case. The mean time between OLT and diagnosis of the recurrence was 21 months (range, 3–53). Seven cases recurred before 12 months, 6 cases at 12–24 months, 5 cases at 24–48 months, and 1 case at 53 months. The mean time between recurrence and death was 2.9 months (range, 1–16). Of the 19 patients in whom the tumor recurred, 17 died as a result, one has survived 2 months with the recurrence, and the other died in the immediate postoperative period from multiorgan failure after a retransplant.

Mortality

Sixty-four percent (23 of 36) of the patients died: 17 (47%) due to tumor recurrence; the other 6 (17%) from non–tumor-related causes. Of these 6 patients, 3 (8%) died in the first 3 months (1 case for primary graft failure, 1 case for cerebral infarction, and 1 case for sepsis); one patient died at 36 months after retransplantation for chronic rejection; another patient died at 37 months due to an adenocarcinoma of the rectum; and the remaining patient died at 76 months from lung cancer.

Survival

The accumulated survival of the 36 patients was 55 ± 11 months; survival at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years was 82%, 53%, 30%, respectively, and 18%, and disease-free survival at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years was 77%, 53%, 30%, and 18%, respectively. The 5-year survival rate of the patients with tumor recurrence was 5% versus 71% for those without recurrence (P < 0.0001). The accumulated survival of the patients who died of tumor recurrence (n = 17) was 26 ± 4.4 months, similar to that of the patients who died of non–tumor-related causes (n = 6; 26 ± 12 months; P = 0.923). Of the 13 patients still alive, 8 are stages I—II, with a mean survival of 69 months (range, 3–162); 5 are stages III—IV, with a mean survival of 28 months (range, 5–62).

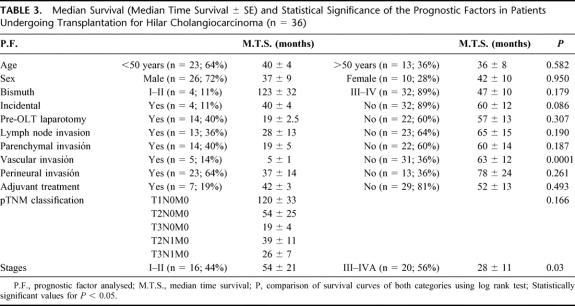

Prognostic Factors

In the univariate analysis (Table 3), SS factors of poor prognosis were vascular invasion (P < 0.0001) (0% survival at 3 years, when vascular invasion was present, compared with 63% and 35% at 3 and 5 years, respectively, when it was not) and stages III-IVA (P < 0.05) (15% survival at 5 years versus 47% for stages I–II). Lymph node and perineural invasion reduce survival, although the differences were not SS (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, factors of poor prognosis were again vascular invasion (P < 0.01) and stages III–IVA (P < 0.01).

TABLE 3. Median Survival (Median Time Survival ± SE) and Statistical Significance of the Prognostic Factors in Patients Undergoing Transplantation for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 36)

Peripheral Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 23)

Tumor Recurrence

Eight patients (35%) presented with tumor recurrence. The most common site of recurrence was the abdominal cavity with 5 cases (liver in 3 cases and peritoneum in 2 cases), pulmonary metastases in 2 cases, and multiple metastases in 1 case. The mean time between OLT and recurrence was 22 months (range, 5–75). Three cases recurred before 12 months, 3 cases at 12–24 months, 3 cases at 24–48 months, 1 case at 39 months, and 1 case at 75 months. The mean time between recurrence and death was 6.6 months (range, 1–13). Of the 8 patients with recurrence, 7 died as a result, and 1 has survived 15 months with the recurrence.

Mortality

Eleven (48%) of the 23 patients died, 7 (30%) due to tumor recurrence and the other 4 (18%) for non–tumor-related causes. Of these 4 patients, 2 (8.6%) died in the first 3 months (1 for chronic rejection and 1 for multiorgan failure), 1 patient died at 12 months due to adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, and 1 patient died at 72 months due to acute myocardial infarction.

Survival

The actuarial survival rate was 77%, 65%, 42%, and 23% at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years, respectively, and disease-free survival was 68%, 45%, 27%, and 23% at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years, respectively. Accumulated survival was 66 ± 17 months. The 3- and 5-year survival rates when there was tumor recurrence were 50% and 16%, versus 78% and 78% when there was no recurrence (P < 0.05).

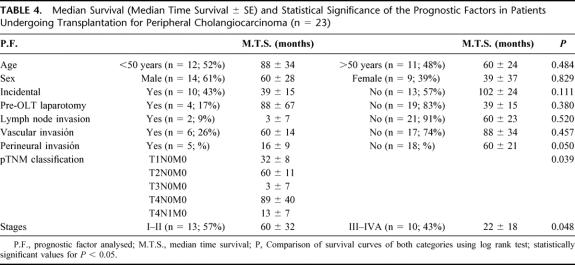

Prognostic Factors

In the univariate analysis, pTNM classification was SS (P < 0.05) (Table 4), with stages I–II presenting a better survival rate at 3 and 5 years (80% and 40%, respectively) than stages III–IVA (46% and 31%, respectively). In the multivariate analysis, perineural invasion (P < 0.05) and stages III–IVA (P < 0.05) were SS.

TABLE 4. Median Survival (Median Time Survival ± se) and Statistical Significance of the Prognostic Factors in Patients Undergoing Transplantation for Peripheral Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 23)

DISCUSSION

The treatment of HCC, when there is dissemination, is palliative (drains, prothesis, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), but it achieves little or no survival.8,9 When the HCC is not disseminated, the ideal treatment is surgical resection of the tumor with free margins (R0 resection), a treatment that obtains acceptable survival rates (40–50% at 5 years). However, the R0 resection rate achieved is low, related to the early invasion of neighboring vascular structures, the level of the lesion,5,13 the surgeon's experience (the resection rate varies from 10% to 90% depending on the hospital),15–18 and the type of surgical technique (local resection achieves 20–30% of R0, and hepatic resection 50–70%). When there is microscopic invasion of the resection margins (R1 resection), 5-year survival ranges from 10% to 20%; when there is macroscopic invasion of the resection margins (R2 resection), the 5-year survival rate is 0%.1–5,15,20–22

When the HCC is not disseminated and surgical resection has been impossible, palliative treatment is implemented, with a poor survival rate. In these cases, as OLT is locally more aggressive, it might achieve complete resections in tumors in which resection is otherwise going to be incomplete (R1 and R2 resections).21 In a search for more surgical aggressiveness, some authors associate CPD with the OLT,23 and even Starlz et al24 extend resection to other neighboring organs with the “cluster transplantation.” OLT, therefore, has the advantage of being more radical and technically simple, but it has the disadvantage of immunosuppression, which favors the spread of tumor remains that might go unnoticed. Analysis of the results shows that generally it is indicated in more evolved tumors that have already been considered irresectable by surgeons with experience in liver surgery.9,11,12,21,25

In the OLT series for HCC,6,9,11,12,16,25 the 5-year survival rate ranges from 0% to 38%; with a greater aggressiveness (cluster transplantation), it ranges from 9% to 38%.16,21,24 This survival rate is lower than obtained by OLT indicated for other reasons, and some centers, due to the lack of organs, consider OLT to be contraindicated for HCC.

It is a well-known fact that the fundamental cause of death following OLT is tumor recurrence (occurring in 56–96%),5,11,12,16,21,24 generally abdominal, which occurred in 53% of our patients, 47% dying as a result. It occurs early, as in our series (mean time to recurrence was 21 months). In the Cincinnati Transplant Tumor Registry series,11 51% presented with recurrence, although the time to recurrence was shorter (9.7 months). It is therefore important to know the tumor factors responsible for such recurrence. Lymphatic invasion is considered a factor of early recurrence (0% survival at 5 years with lymphatic invasion, compared with 27% without invasion in the Pittsburgh series).12 In our series, lymphatic invasion also reduced survival (15% at 5 years versus 35% when there was no lymphatic invasion), although it was not SS. Vascular invasion implied a poor prognosis in our series, in both the univariate and multivariate study. HCC has a great affinity with the nerves, through which the tumor spreads, with perineural invasion considered a factor of poor prognosis12,21 (in our series, the 5-year survival rate was 20% when perineural invasion existed, compared with 38% when it did not). pTNM classification has been correlated with the prognosis of these patients in most series. Iwatsuki et al12 report that stages I–II presented a longer survival than stages III–IV (P < 0.038), and T1-T2 patients had a longer survival than T3 patients (P < 0.038). Neuhaus et al,21 in 15 patients receiving transplantation for HCC, find that stages I–II had a similar survival rate to stage IV, whereas no stage III patient lived beyond 40 months. In our series, the early stages (stages I–II) presented a 5-year survival rate of 47%, whereas it was 15% in stages III–IV.

To improve survival, it is important to make a good patient selection (stages I–II and R0 resections have an acceptable survival rate),11 reduce posttransplant mortality (in most series the 3-month mortality rate is currently around 10%), and improve adjuvant therapies (chemotherapy and radiotherapy).

With our results, contraindicating OLT for a nondisseminated irresectable HCC is not ethically simple, especially in a young patient, as there is no palliative treatment that achieves 20–40% survival at 5 years. However, if we indicate OLT, it would be very important to make a good patient selection (excluding patients presenting with factors of poor prognosis), as the 5-year survival rate is around 50% in the early stages, and it would be important to have adjuvant therapies that improve survival.

Postoperative external radiotherapy and chemotherapy did not improve the survival rate in most series, nor did it improve survival in our 7 patients in whom it was used. The Mayo Clinic28 proposes a very rigorous protocol of patient selection for OLT for CC, to which they apply external radiotherapy, chemotherapy with 5-FU, and internal radiotherapy with an Iridium catheter. Of 918 patients who were attended for this clinical entity between 1993 and 1998, only 13 underwent transplantation (12 were stage I–II and 1 stage IVA): the postoperative mortality rate was 0%; survival up to publication was 100%, with a mean of 42 months (range, 12–89 months); and there was a recurrence at 40 months (stage IVA). The good results with this protocol must be influenced by 2 main factors: on the one hand, internal radiotherapy (useful for controlling perineural and wall invasion), since external radiotherapy and chemotherapy had already been used with discouraging results; on the other, strict selection of patients, as most were stages I–II unlike other series and our own, in which stages III–IV exceeded 40%. However, they are very encouraging results; as Bismuth29 suggests, it would be important to do a randomized control trial of transplantation with and without chemo-irradiation in patients with HCC.

The ideal treatment of PCC is liver resection; Madariaga et al published higher 5-year survival rates than for HCC (8% with HCC versus 38% with PCC).1 The survival rate with OLT ranges from 16% to 42% in most series.12,25,30 In our series, the 5-year survival rate for PCC was higher (42%) than for HCC (30%). Our mortality rate was 48%, with 35% tumor recurrence and a mean time between OLT and recurrence of 22 months, similar to HCC.

To obtain early detection of PCC in patients with PSC (incidental CC),26,27 it would be important to improve the results of OLT. PSC predisposes to the development of CC (approximately 10% of PSCs will present a CC), and this incidental CC, as happens with incidental hepatocarcinoma, was thought to have a better prognosis. However, in some series11 the survival rate with incidental CC was similar to CC diagnosed preoperatively, as occurred in our series, with both HCC and PCC.

As for prognostic factors, it must be noted that lymph node invasion, although not SS, presented a worse survival rate (median survival of 3 months compared with 60 months when lymph node invasion did not exist). Perineural invasion and pTNM classification (the 3- and 5-year survival rates in stages I–II were 80% and 40%, versus 46% and 31% in stages III–IV) were significant in the multivariate analysis. As with HCC, we consider the survival rate acceptable, as we are dealing with nonselected patients who have been considered irresectable and in whom palliative treatments are ineffective.

In short, our results confirm that with irresectable HCC and PCC without evidence of tumor spread, OLT achieves higher 3- and 5-year survival rates than reported with palliative treatments, especially in tumors in their early stages. However, considering the lack of organs and the possibility that the situation of the tumor disease might change while on the waiting list, the indication for OLT in these patients could be questioned from an ethical point of view. Living donor liver transplantation might be a valid alternative. Furthermore, information is still needed to help better select CC patients who could really benefit from OLT.

Footnotes

Reprints: Ricardo Robles Campos, MD, Professor of Surgery, Unidad de Cirugía Hepática y Trasplante de hígado-Pancreas, El Palmar, 30120, Murcia, SPAIN. E-mail: rirocam@um.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, et al. Liver resection for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinomas. Ann Surg. 1998;227:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihiliar and distal tumor. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, De Matteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakayama K, et al. Parenchima-preserving hepatectomy in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Von Wasilewski R, et al. Resection surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factor. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washburn WK, Lewis D, Jenkins RL. Aggressive surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1995;130:270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurshinoff BW, Armtrong JG, Fong Y, et al. Palliation of irresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma with biliary drainage and radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueras J, Lladó L, Valls C, et al. Changing strategies in diagnosis and management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Transplant. 2000;6:786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busuttil RW, Farmer DG. The surgical treatment of primary hepatobiliary malignancy (review). Liver Tranpl Surg. 1996;2(suppl. 1):114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer CG, Penn I, James L. Liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma: results in 207 patients. Transplantation. 2000;69:1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Marsh W, et al. Treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klastkin tumors) with hepatic resection or transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobin LH, Wittekind CH, eds. TNM classification of management tumors, 5th ed, New York: Wiley, 1997:81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Comparison of an American and Japanese experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Launois B, Terblanche J, Lakehal M, et al. Proximal bile duct cancer: high respectability rate and 5-year survival. Ann Surg. 1999;230:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed DN, Vitale GC, Martín R, et al. Bile duct carcinoma: trends in treatment in the nineties. Am Surg. 2000;66:711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura Y, Kawarada Y. Surgical strategies for carcinoma of the hepatic duct confluence. Br J Surg. 1998;85:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatic segmentectomy with caudate lobe resection for bile duct carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. W. J Surg. 1990;14:535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, et al. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1999;230:808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukada K, Yoshida K, Aono T, et al. Major hepatectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy for advanced carcinoma of the biliary tract. Br J Surg. 1994;81:108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuhaus P, Blumhardt G. Extended bile duct resection: a new oncological approach to the treatment of central bile duct carcinomas? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1994;379:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starzl TE, Todo S, Tzakis AG, et al. Abdominal organ cluster transplantation for the treatment of upper abdominal malignancies. Ann Surg. 1989;210:374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casavilla FA, Marsh JW, Iwatsuki S. Hepatic resection and transplantation for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;185:429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gores GJ. Early detection and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Transplant. 2000;6:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nashan B, Schlitt HJ, Tusch G, et al. Biliary malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis: timing for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;23:1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Vreede I, Steer JL, Burch PA, et al. Prolonged disease-free survival after orthotopic liver transplantation plus adjuvant chemoirradiation for cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Transplant. 2000;6:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bismuth H. Revisiting liver transplantation for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Mayo Clinic proposal. Liver Transplant. 2000;6:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berdah SV, Delpero JR, Garcia S, et al. A western surgical experience of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]